Quick links

- Make a Gift

- Directories

What is Humanities Research?

Research in the humanities is frequently misunderstood. When we think of research, what immediately comes to mind for many of us is a laboratory setting, with white-coated scientists hunched over microscopes. Because research in the humanities is often a rather solitary activity, it can be difficult for newcomers to gain a sense of what research looks like within the scope of English Studies. (For examples, see Student Research Profiles .)

A common misconception about research is reinforced when we view it solely in terms of the discovery of things previously unknown (such as a new species or an archaelogical artifact) rather than as a process that includes the reinterpretation or rediscovery of known artifacts (such as texts and other cultural products) from a critical or creative perspective to generate innovative art or new analyses. Fundamental to the concept of research is precisely this creation of something new. In the humanities, this might consist of literary authorship, which creates new knowledge in the form of art, or scholarly research, which adds new knowledge by examining texts and other cultural artifacts in the pursuit of particular lines of scholarly inquiry.

Research is often narrowly construed as an activity that will eventually result in a tangible product aimed at solving a world or social problem. Instead, research has many aims and outcomes and is a discipline-specific process, based upon the methods, conventions, and critical frameworks inherent in particular academic areas. In the humanities, the products of research are predominantly intellectual and intangible, with the results contributing to an academic discipline and also informing other disciplines, a process which often effects individual or social change over time.

The University of Washington Undergraduate Research Program provides this basic definition of research:

"Very generally speaking, most research is characterized by the evidence-based exploration of a question or hypothesis that is important to those in the discipline in which the work is being done. Students, then, must know something about the research methodology of a discipline (what constitutes "evidence" and how do you obtain it) and how to decide if a question or line of inquiry that is interesting to that student is also important to the discipline, to be able to embark on a research project."

While individual research remains the most prevalent form in the humanities, collaborative and cross-disciplinary research does occur. One example is the "Modern Girl Around the World" project, in which a group of six primary UW researchers from various humanities and social sciences disciplines explored the international emergence of the figure of the Modern Girl in the early 20th century. Examples of other research clusters are "The Race/Knowledge Project: Anti-Racist Praxis in the Global University," "The Asian American Studies Research Cluster," " The Queer + Public + Performance Project ," " The Moving Images Research Group ," to name a few.

English Studies comprises, or contains elements of, many subdisciplines. A few examples of areas in which our faculty and students engage are Textual Studies , Digital Humanities , American Studies , Language and Rhetoric , Cultural Studies , Critical Theory , and Medieval Studies . Each UW English professor engages in research in one or more specialty areas. You can read about English faculty specializations, research, and publications in the English Department Profiles to gain a sense of the breadth of current work being performed by Department researchers.

Undergraduates embarking on an independent research project work under the mentorship of one or more faculty members. Quite often this occurs when an advanced student completes an upper-division class and becomes fascinated by a particular, more specific line of inquiry, leading to additional investigation in an area beyond the classroom. This also occurs when students complete the English Honors Program , which culminates in a guided research-based thesis. In order for faculty members to agree to mentor a student, the project proposal must introduce specific approaches and lines of inquiry, and must be deemed sufficiently well defined and original enough to contribute to the discipline. If a faculty member in English has agreed to support your project proposal and serve as your mentor, credit is available through ENGL 499.

Beyond English Department resources, another source of information is the UW Undergraduate Research Program , which sponsors the annual Undergraduate Research Symposium . They also offer a one-credit course called Research Exposed (GEN ST 391) , in which a variety of faculty speakers discuss their research and provide information about research methods. Another great campus resource is the Simpson Center for the Humanities which supports interdisciplinary study. A number of our students have also been awarded Mary Gates Research Scholarships .

Each year, undergraduate English majors participate in the UW's Annual Undergraduate Research Symposium as well as other symposia around the nation. Here are some research abstracts from the symposia proceedings archive by recent English-major participants.

UW English Majors Recently Presenting at the UW's Annual Undergraduate Research Symposium

For additional examples, see Student Profiles and Past Honors Students' Thesis Projects .

- Newsletter

- Enroll & Pay

Why the humanities?

What are the humanities and why do they matter.

The humanities include disciplines such as history, literature, philosophy, and religious studies; they feature prominently in interdisciplinary departments such as African and African American Studies, Indigenous Studies, and Women’s, Gender, and Sexuality Studies; they also have much in common with the arts and social sciences.

These disciplines help us to understand who we are, what it means to be human, how we relate to others, and the pathways that have led us to this point in time. We cannot navigate our way through the present into the future without a balanced understanding of our diverse, complicated, and often problematic pasts. Appreciating what it means to be human, how relationships work, and how perspectives on these questions vary from culture to culture – these are crucial to our present and future. The humanities take us there.

In a rapidly transforming world and workplace, we need more than ever to nurture critical thinking and the capacity for problem-solving. As a growing number of employers are pointing out, specific skills become increasingly ephemeral in an ever-changing workplace; what they need are employees who can analyze carefully, think creatively, and express themselves clearly, skills fostered by the humanities. Those skills are and will be crucial ingredients for professional success in the bracing twenty-first century workplace. The humanities take us there.

Literacy and critical thinking also play a crucial role in the democratic process, which depends on a citizenry prepared to engage actively and thoughtfully with current events, committed to creative and innovative solutions instead of blind deference to tradition and authority, and watchful of our hard-won freedoms. The humanities take us there.

Every day we witness the many ways in which the world around us becomes ever more interconnected and yet remains deeply divided. The humanities help nurture connections within and between diverse societies, offering pathways for constructive engagement. Learning about and respecting outlooks different from our own is crucial to our survival in the twenty-first century, moving us away from tensions created by ignorance and fear toward informed, sympathetic conversation between cultures. That does not mean forsaking our own identities and loyalties, but it does involve developing the capacity to see beyond them. The humanities take us there.

The expansion of humanistic inquiry in recent decades to recover the voices and past lives of people who have been either ignored or systematically removed from historical narratives and literary canons fits closely with broader trends in our culture toward greater inclusion and a recognition of diverse voices and histories. We are an indispensable part of that process as we seek to understand the many constituent parts that together make up the complex world we inhabit. The humanities take us there.

The humanities are not an optional and unaffordable luxury, as some critics would have us believe. What we do as humanities scholars and in our classrooms could not be more relevant to the world we live in; nor could they be more practical in terms of the skills we need as twenty-first-century citizens. The humanities are a necessity – and not only from a utilitarian perspective. We cannot surrender to a vision of the future that fixates on a narrow economic conception of what is productive and useful. What about our responsibility to nurture our individual capacity for creativity and artistic expression? These are also crucial measurements of our worth, success, and wealth as human beings. We should never undervalue the personal fulfillment and happiness that we can draw from literature, art, music, theater, philosophy, religious studies, and history. An appreciation of our diverse cultural legacies enriches our lives, individually and collectively, and the same is true of becoming actively involved as participants in the creation of new cultural forms. As a growing body of research demonstrates, cultural vitality and personal happiness ultimately lead to economic growth. The humanities take us there.

Please join the quest to support, create, and disseminate new ideas that open our minds, reveal new ways of understanding who we are, and uncover the histories that brought us to the moment we now live in!

(By Richard Godbeer, former director of the Hall Center for the Humanities)

The Hall Center, one of 11 designated research centers that fall under the auspices of the University of Kansas Office of Research, provides an intellectual hub for scholars in the humanities and fosters interdisciplinary conversation across the University of Kansas. Through its public programming, the Hall Center makes visible the significance and relevance of humanities research, engaging broad, diverse communities across the state in dialogue about compelling local, national, and global issues that humanities research addresses. The Hall Center acts on the conviction that the humanities must play a critical role in constructing a humane future for our world.

Humanities in Action

Perspectives. Resources. Involvement.

What Are the Humanities?

What do they “do” why are they so important.

Put simply, the humanities help us understand and interpret the human experience, as individuals and societies.

But humanities fields are under threat. Funding for key humanities agencies and programs has been targeted for cuts affecting communities across the country. College and university humanities departments face closures and mergers. More college classes are being taught by contingent faculty members who make too little for teaching too many students.

We believe that everyone can make a difference, and we created the Humanities in Action site for people like you—scholars, teachers, and citizens— to help you connect, learn more, and get involved. The Humanities in Action site features news about the humanities and highlights perspectives from leading humanists on compelling issues ; provides information about public policies affecting humanities research, education, and public programs; and offers resources and opportunities for you to act.

- Skip to main content

- Skip to footer

UCI Humanities Core

Research in the Humanities

By Matt Roberts Revised for 2018-19

Introduction

Welcome to the University of California, Irvine! As a student enrolled in the Humanities Core program, you will study a variety of cultural artifacts related to the theme of “Empire and Its Ruins.” Research will be important to your engagement with course material and topics, and the UCI Libraries is here to help you.

The UCI Libraries is home to several research librarians, who can provide you with expert service. To learn more, please visit the UCI Libraries’ Directory of Research Librarians .

To take advantage of the UCI Libraries’ resources for Humanities Core, please visit the Humanities Core Research Guide . You find the guide by visiting the UCI Libraries’ home page. Then click on the “ Research Guides ” Quick Link.

What is Humanities Research?

It is worth asking what it means to do research in the Humanities. As David Pan (Professor of German, UCI School of Humanities) writes, “[i]nterpretation is the primary method of the humanities because the meaning that humanities scholars search for is not a constant one. Rather, standards of meaning change when one moves in time and space from one cultural context to another. Negotiating this movement is the primary task in humanities inquiry” (6) .

As Pan emphasizes, humanities work is an interpretive process. For instance, for your first major writing assignment, you must perform a close reading of a passage from the Aeneid . You will describe how the selection’s formal elements—such as symbolism or diction—support an overarching theme in the epic as a whole. While this assignment does not require that you conduct research related to the Aeneid , it nevertheless invites you to research the meaning of “symbolism” or “diction.” Let us therefore assess our information need and design a process to find the definition of, for example, diction.

Question: Where do we find the definition of a word or specialized term such as “diction”?

Answer: We find definitions in a dictionary.

Note that as the Aeneid is an epic poem, it is important to determine what “diction” means within a literary context. Therefore, let’s consult a dictionary of literary terms.

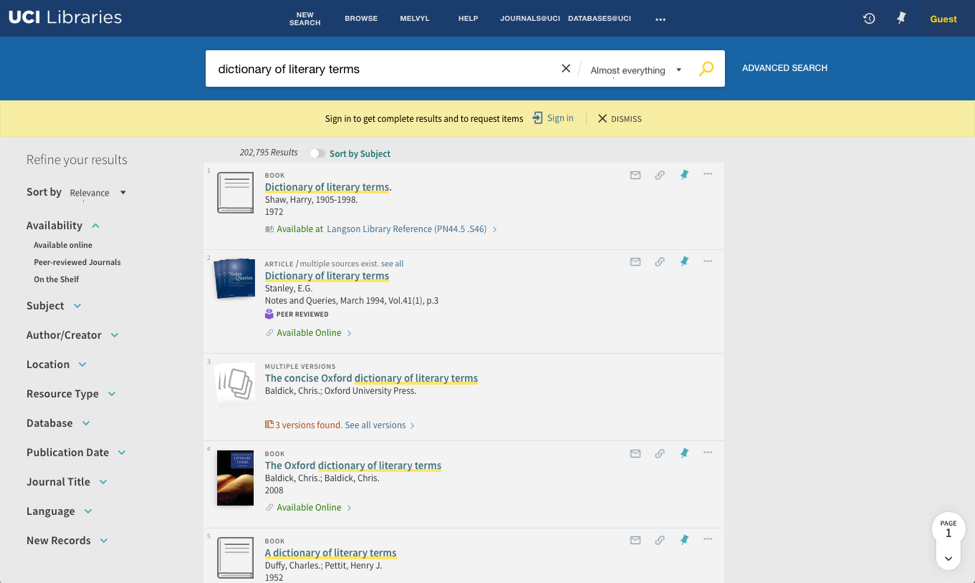

Question : How do we find a dictionary of literary terms?

Answer: Consult the UCI Libraries’ webpage . Then search Library Search , the new finding aid for the UCI Libraries’ catalog. Since we don’t know the exact title of the dictionary that we might use, we can simply search for “dictionary of literary terms.”

We must choose the title that best matches our information need. I chose The Oxford Dictionary of Literary Terms because Oxford University Press publishes exemplary reference materials. The green “Available Online” link takes me directly to this resource. I can then use the resource to search for the definition of “Diction.”

So, what have we learned?

- Research begins with a question (“What is diction?”).

- The research question(s) that we ask helps us to discover information.

- The kind of information that we need to discover will often determine what UCI Libraries’ resource to consult (e.g., a book, reference resource, database, etc.).

- Discovering information helps us to interpret an object of study.

- The interpretation of the object of study enables us to craft clearly argued responses to writing assignments.

In other words, humanities research is a strategic exploration whereby information discovery facilitates your interpretive abilities.

Doing Research: Primary Sources and Secondary Sources

As we have already noticed, the research process involves the ability to discover a source that provides information of some kind. It is therefore important to distinguish between sources so that you can readily access that information.

Scholars typically distinguish between kinds of sources, particularly between primary and secondary sources. As you will be reading a variety of texts this year, it is important to recognize that texts are not objectively primary or secondary. Ultimately, the extent to which sources are primary depends upon the questions you ask about them and the way that you use them (Arndt 93). For instance, a primary source is an object that bears witness to a historical event. Primary sources therefore call us to consider how they make meaning of the event to which they bear witness. On the other hand, secondary sources interpret a primary source. For example, if you were to write a paper that interprets how diction in the Aeneid characterizes human experience, you would be creating a secondary source.

Determining the difference between a primary source and a secondary source can be difficult. Let us explore each type of source in greater detail so that we can begin to understand what types of question we can ask of primary sources, and how we can engage with them in order to research secondary source material.

Primary Sources

On your syllabus, you will find a variety of texts, or sources, that you will read over the course of the year. In the fall quarter, these texts include, but are not limited to:

- Virgil’s Aeneid (19 B.C.E.)

- Jean-Jacques Rousseau’s “Discourse on the Origin and Foundations of Inequality among Men” (1754/1755)

- J.M. Coetzee’s Waiting for the Barbarians (1980)

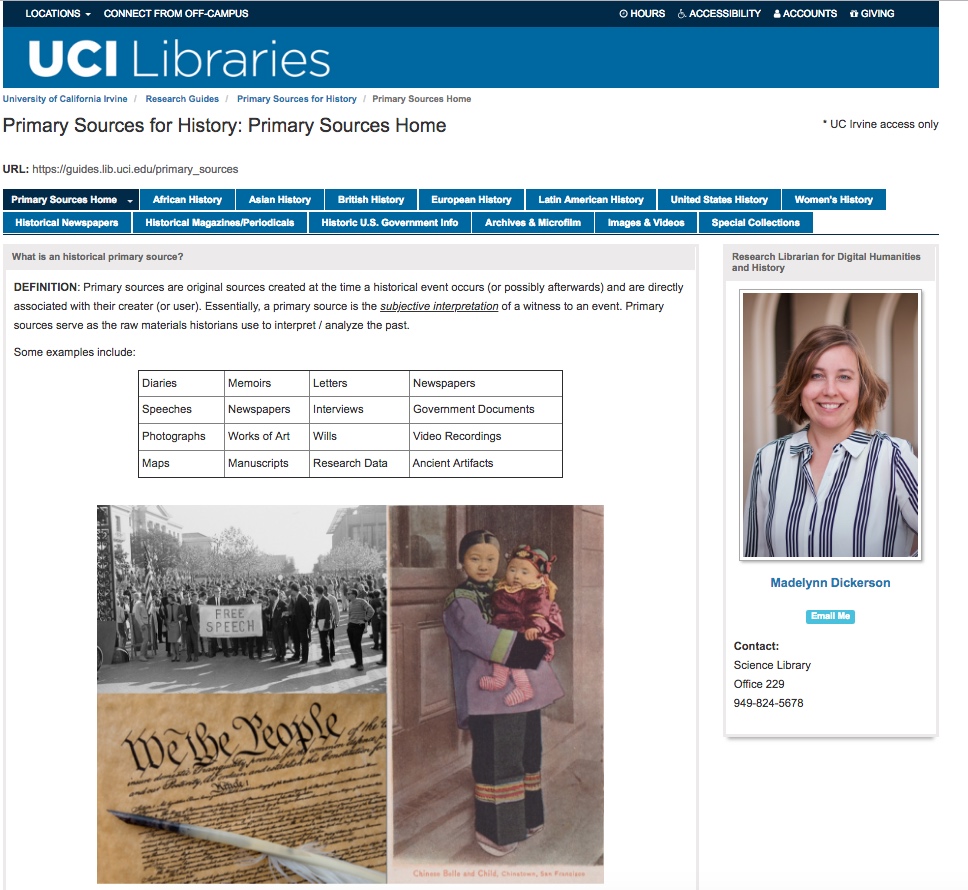

These are generally considered to be primary sources, but how can you be sure? To answer this question, consult the Primary Sources Research Guide , curated by the UCI Libraries’ History Librarian, Madelynn Dickerson.

According to this Research Guide, primary sources can include diaries, memoirs, letters, newspapers, speeches, interviews, government documents, photographs, works of art, video recordings, maps, manuscripts, data, and physical artifacts.

Question: Is the Aeneid a primary source?

Answer: Yes. Most often it qualifies because it is a work of art, specifically an epic poem. However, one might use the Fagles’ version of The Aeneid as a secondary source, demonstrating how the translation is an interpretation of the original Latin text and using that analysis to offer one’s own interpretation of the epic poem. You can learn more about the interpretive politics of translation from Giovanna Fogli and Nuccia Malinverni’s chapter on “Translation” in your Writer’s Handbook .

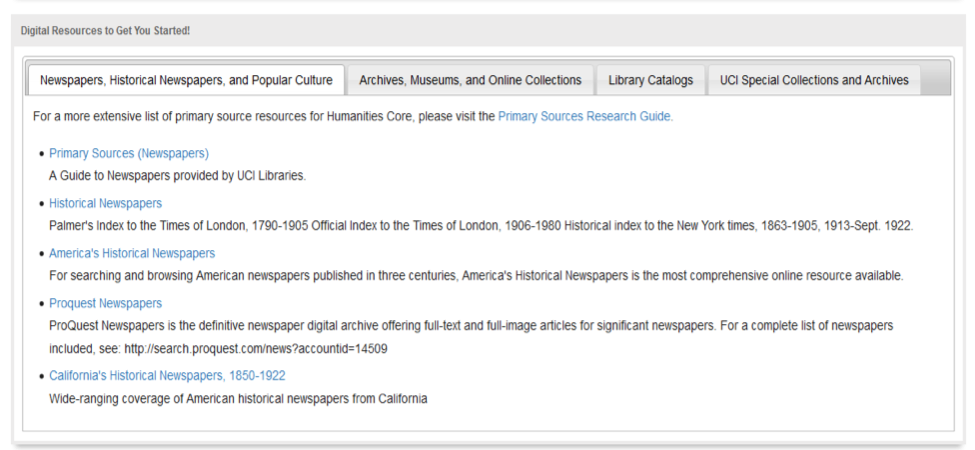

Throughout the year, you will be encouraged to find primary sources related to the topic of Empire and Its Ruins. To do this, it is useful to visit the Humanities Core Research Guide . Select the “ Primary Sources and Artifacts” tab to locate primary source discovery resources.

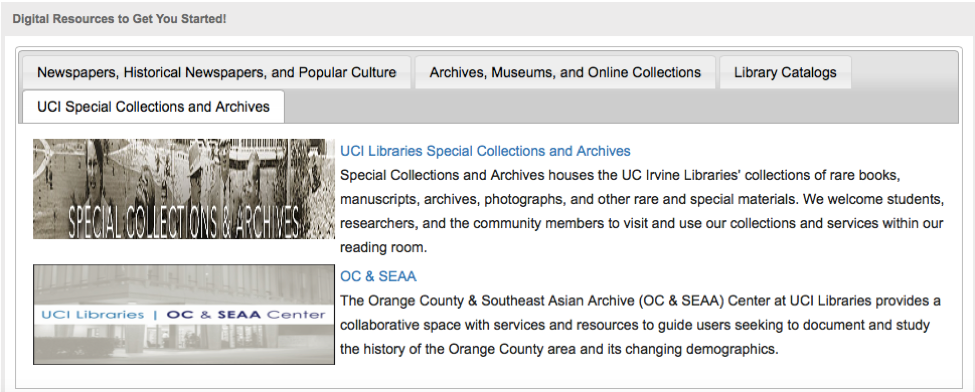

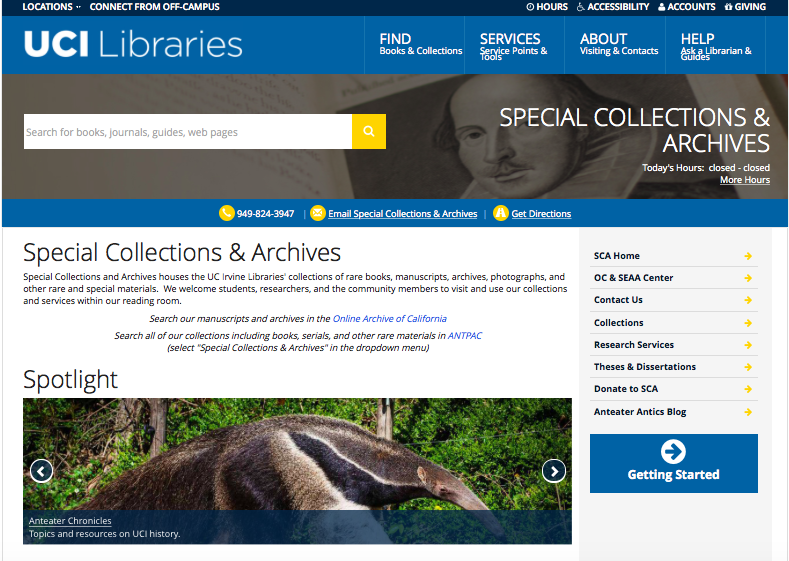

Additionally, you will have the unique opportunity to visit the Special Collections and Archives .

Follow the link to the SCA webpage, and you can discover a variety of primary source collections. Be sure to also visit the UCI Libraries’ Southeast Asian Archive webpage for a wealth of primary sources related to Empire and Its Ruins.

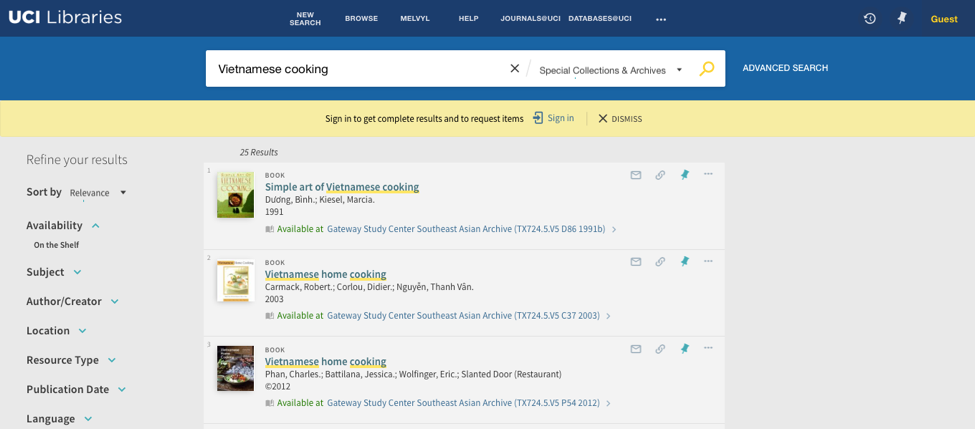

You can also use Library Finder to find primary sources and cultural artifacts in the SCA collection.

When analyzing a primary source, it is important to ask certain questions. Questions such as those listed below will help you to discover information, which you can use to interpret a primary source. In other words, questions such as these will help you to determine how a primary source makes meaning of the event to which they bear witness.

- Who made the primary source? What was that person’s race, gender, class? How, if at all, would that matter within the historical period in which the source is created? (Authorship)

- Where, when, and why was the primary source written/made? Does it describe specific attitudes of a historical period and place? What motivated its production? (Historical Context)

- For whom was the primary source written/made? For public or private use? Was it reproduced for a mass audience? How might that audience have used or responded to this source? (Audience)

- Of what is the primary source made? How might that shape how the source is understood and interpreted? (Materiality)

- What are the limitations of this type of source? What can’t it tell us? For whom is it not made available?

Simple questions such as these can help you to formulate more sophisticated research questions or topics of inquiry. You may therefore want to examine other primary sources or search for how expert scholars interpret the primary source that interests you.

Secondary Sources

When you do research, you are embarking on a journey that requires you to engage with how others interpret the primary source or sources that interest you. Whereas primary sources are original works that document an event as it took place, a secondary source interprets a primary source, often long after it was created. Secondary sources include, but are not limited to: Peer-reviewed academic books; chapters published in peer-reviewed academic books; peer-reviewed journal articles; newspaper and magazine articles published after, and therefore not explicitly covering, a historical event. Peer-reviewed works are considered to be most reliable in academic settings because they have been scrutinized and vetted by scholars to determine if the research presented makes a significant contribution.

Question : How do we find peer-reviewed journal articles?

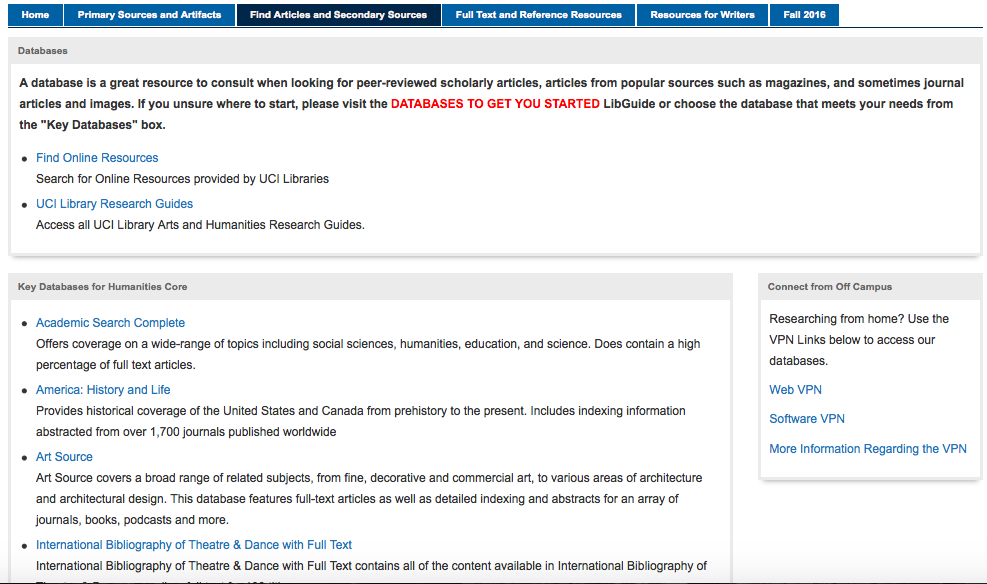

Answer: Let’s return to the Humanities Core Research Guide, where we will find links to, and descriptions of, the databases related to Humanities Core. Select the “ Find Articles and Secondary Sources” tab to find peer-review journal articles.

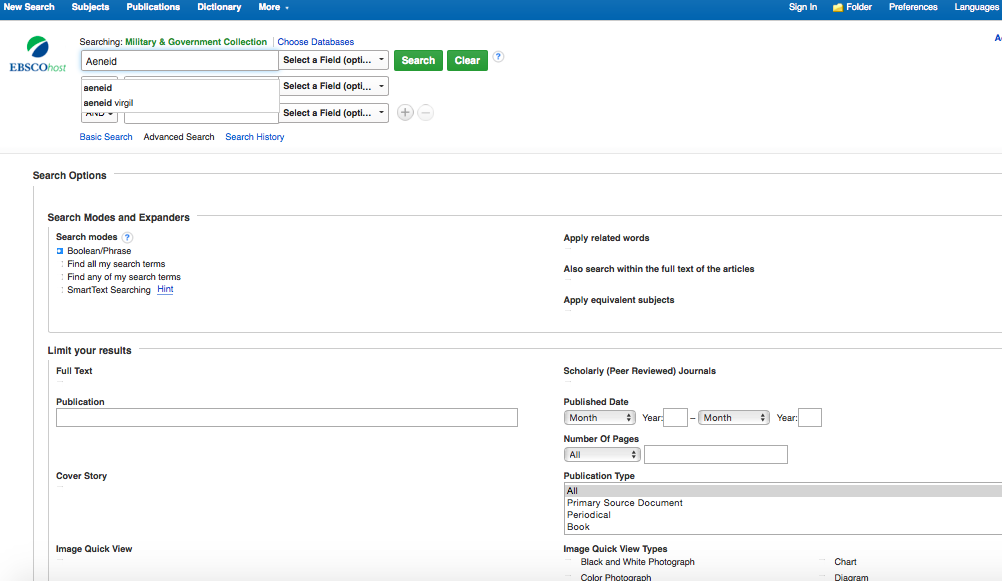

I began my search with Academic Search Complete , which covers a wide-range of topics including social sciences, humanities, education, and science. It is therefore a good place to begin to do secondary source research. However, you can consult other databases such as the MLA International Bibliography , Project Muse , or JSTOR .

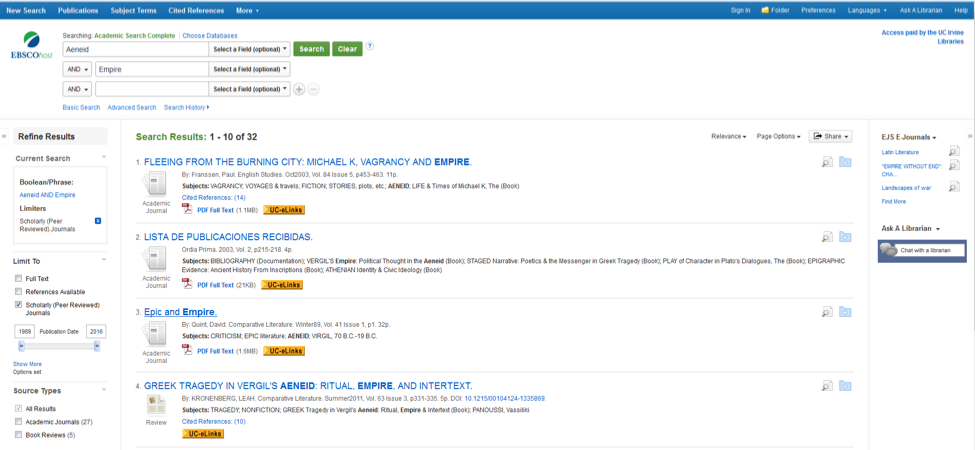

The above screen shot indicates how one might find scholarly articles related to the topic of the Aeneid and Empire. I also checked the “Scholarly (Peer Reviewed) Journals” box to limit my results. This search populates the following result list:

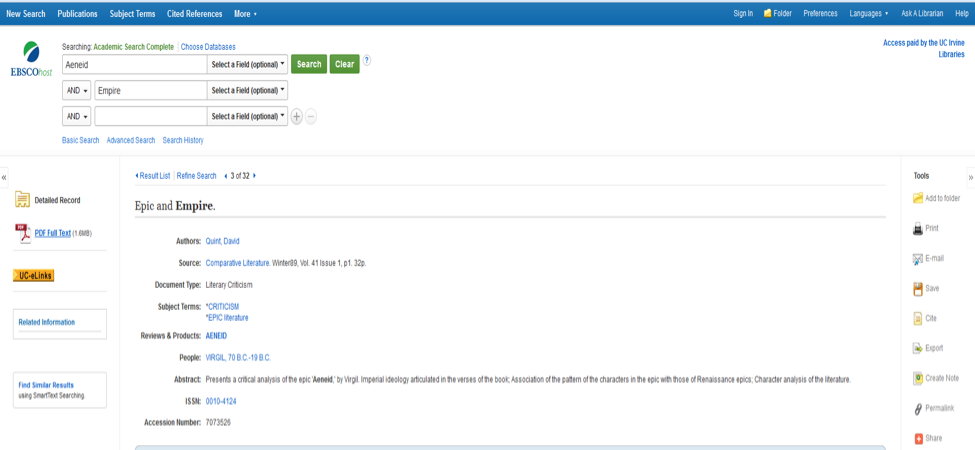

The article entitled “ Epic and Empire” appears directly related to our search. Selecting that article will open up the record for the article.

For this article, we can click on the “PDF Full Text” icon and download the article. For articles that do not have a link to the PDF, please click on the “UC E-Links” icon to search for alternative methods of access.

Please remember that secondary sources are interpretations. Consequently, as a researcher, situate yourself in an active role. In this way, you will understand that secondary sources should not speak for you or instead of you. Rather, you should integrate them into your analysis of a primary source to demonstrate your own contribution to a scholarly conversation on a topic that interests you. We do not do research simply to communicate how others have interpreted a primary source. We do research to discover how to interpret something for ourselves.

- Primary sources are original sources created at the time a historical event occurs and are directly associated with their creator. A primary source is the subjective interpretation of a witness to an event.

- Secondary sources are scholarly or popular sources that interpret a primary source and can be created long after the primary source was created.

- Research is a process that requires us to question and interrogate the information that we discover in order to interpret an object of study. It requires the evaluation and integration of both primary and secondary sources.

- The UCI Libraries have several research resources that can help you to discover and choose primary sources and secondary sources that interest you.

- Research Librarians at the UCI Libraries are here to help you!

Please note that you will be able to take advantage of several of the UCI Libraries’ instruction and reference services throughout the year. You can meet with research librarians who specialize in specific disciplines to learn more about conducting searches and vetting sources.

Works Cited

Arndt, Ava. “What to do with Primary Sources.” Humanities Core Writer’s Handbook: War, edited by Larisa Castillo, Pearson, 2014, pp. 90-94.

Baldick, Chris. “Diction.” The Oxford Dictionary of Literary Terms . 3 rd ed., 2008. doi:10.1093/acref/9780199208272.001.0001. Accessed 12 September 2016.

Imamoto, Rebecca. Primary Sources for History: Primary Sources . University of California, Irvine. Sept. 2016. http://guides.lib.uci.edu/primary_sources. Accessed 12 September 2016.

Pan, David. “What are the Humanities?” Humanities Core Writer’s Handbook: War , edited by Larisa Castillo, Pearson, 2014, pp. 5-9.

Quint, David. “Epic and Empire.” Comparative Literature , vol. 26, no. 1, 2001, pp. 620-26.1. Academic Search Complete . Web. 16 Sept. 2016. http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=a9h&AN=7073526&site=ehost-live&scope=site. Accessed 16 September 2016.

Roberts, Matthew. Humanities Core Course . University of California, Irvine. Sept. 2016. http://guides.lib.uci.edu/primary_sources. Accessed 12 September 2016.

185 Humanities Instructional Building, UC Irvine , Irvine, CA 92697 [email protected] 949-824-1964 Instagram Privacy Policy

Instructor Access

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- Open access

- Published: 09 April 2019

The place of the humanities in today’s knowledge society

- Rosário Couto Costa ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-7505-4455 1

Palgrave Communications volume 5 , Article number: 38 ( 2019 ) Cite this article

38k Accesses

12 Citations

111 Altmetric

Metrics details

Over the past four decades, the humanities have been subject to a progressive devaluation within the academic world, with early instances of this phenomenon tracing back to the USA and the UK. There are several clues as to how the university has generally been placing a lower importance on these fields, such as through the elimination of courses or even whole departments. It is worth mentioning that this discrimination against humanities degrees is indirect in nature, as it is in fact mostly the result of the systematic promotion of other fields, particularly, for instance, business management. Such a phenomenon has nonetheless resulted in a considerable reduction in the percentage of humanities graduates within a set of 30 OECD countries, when compared to other areas. In some countries, a decline can even be observed in relation to their absolute numbers, especially with regards to doctorate degrees. This article sheds some light on examples of international political guidelines, laid out by the OECD and the World Bank, which have contributed to this devaluation. It takes a look at the impacts of shrinking resources within academic departments of the humanities, both inside and outside of the university, while assessing the benefits and value of studying these fields. A case is made that a society that is assumed to be ideally based on knowledge should be more permeable and welcoming to the different and unique disciplines that produce it, placing fair and impartial value on its respective fields.

Introduction

In August 2017, the World Humanities Conference took place in Liège, Belgium. The theme was Challenges and Responsibilities for a Planet in Transition , and it was organized in cooperation with UNESCO. The rationale for this conference can be summarized as follows:

“The humanities were at the heart of both public debate and the political arena until the Second World War. In recent years their part was fading and they have been marginalized. It is crucial to stop their marginalization, restore them and impose their presence in the public sphere as well as in science policies Footnote 1 ”

I participated in this event and it gave me hope that it would be possible to reverse the general trend of devaluating the humanities, something that has been going on since the early 1980s, namely in the UK and in the USA (Costa, 2016 ). Such a phenomenon has coexisted with an acceleration in globalization and a widespread rise of neoliberalism, two trends which have been gradual and simultaneous in their origins (Heywood, 2014 ). In regard to the growth of neoliberalism, while in the 1980s only four countries had what could be reasonably categorized as neoliberal governments (Chile, New Zealand, the UK and the USA), at the beginning of the 21 st century that number had multiplied all around the world (Peck, 2012 ).

This marginalization of the humanities has been a gradual process that manifested itself at different times throughout the countries in which it can be observed. A global approach was used for studying this process (Costa, 2016 ), along with available OECD data which consisted of a subset of thirty countries and recorded the period between 2000 and 2012 Footnote 2 . Under these circumstances, “graduates by field of education” Footnote 3 is arguably one of the few relevant indicators that we can establish. On analysing it, one can conclude that despite some variance in tendencies for each individual nation, there is an overall shift that allows us to confidently corroborate such a devaluation when we compare figures for the year 2000 with those of 2012. This approach was further complemented with the analysis of case studies and existing academic literature on the topic (Costa, 2016 ).

With that in mind, it seems paradoxical that in a so-called knowledge society, one that should be ‘nurtured by its diversity and its capacities’ (UNESCO, 2005 , p.17), not all knowledge fields would be valued in an equitable manner. So why does it happen and why namely at the expense of the humanities? Conversely, what are the reasons for looking at the humanities in a more positive light? These reasons have long been known, but can nowadays lack sufficient recognition. The goal of this comment is to address these questions.

The way to find the answers to these discussion points begins with an analysis of political documents written within the framework of international organisations such as the World Bank and the OECD during the transition into the 21st century. This analysis identifies some political guidelines that have plausibly influenced the global shift in the number of graduates by field of education occuring between 2000 and 2012. Afterwards, we take a look at the impact that these guidelines have had both within and outside of the University. Once done, we reflect on the benefits of studying the humanities and on the complementarity of the various knowledge fields within society.

The political constraints of the devaluation of the humanities in an academic context

Taking into account the already long history of the University, its most recent transformation has been marked by the principles of neoliberalism and the pace of this change has increased since 1998 (Altbach et al., 2009 ). It is in this particular institutional context that the devaluation of the humanities has been taking place. If we pay attention to the general guidelines that have been at the core of this paradigm shift, we can see that the humanities have been confronted not so much with a direct and explicit denial of their benefits, but with the exalting of skills and traits strongly connected to other knowledge fields, such as business administration. This reasoning is based on the following analysis of some specific documents that are enlightening examples of this occurrence.

At The World Conference on Higher Education in the Twenty-First Century , organized by UNESCO in 1998, in Paris, two talks expanded on how the University was already undergoing a process of transformation—one from a practical point of view, and the second from a conceptual one.

In the first talk, titled The Financing and Management of Higher Education: a Status Report on Worldwide Reforms (Johnstone et al. 1998 ), the authors explain how the World Bank implemented its political agenda in order to reform the University throughout the 90s in several countries. A political decision to reduce public investment fundamentally altered the financial and managerial scenarios of the University. A result of this was that the academic sector was steered towards the markets, with an explicit mention in the report that this shift was meant to align with neoliberal principles.

The consistency of this reform has been hailed as remarkable by the cited authors. It has followed similar patterns across all countries independently of existing differences between them with regards to political and economic systems, states of industrial and technological development, and the structuring elements of the higher education system itself.

In the other talk, titled Higher Education Relevance in the 21st Century , Michael Gibbons ( 1998 ), counselor to the World Bank, affirms the urgency of a new paradigm for the University, and theorizes such a transformation. Accordingly, the main mission of the University would be to serve the economy, specifically through the training of human resources, as well as the production of knowledge, for that purpose. Other functions would be cast into the background. In order for this institution to adjust to its new priorities, the author affirms that a new culture would have to impose itself on the University: a new way of considering accountability—so called “new accountability”—with financial accounting at its core; the dissemination of a new practice of highly ideological management (“new public management” or “new managerialism”); and a new way of utilizing human resources with the goal of maximizing efficiency. In short, an entrepreneurial outlook on the concept of “University”.

A few years later, the document The New Economy. Beyond the Hype (OECD, 2001 ) essentially anticipated the impact of the then new model of University on the prioritization of the various fields of knowledge. The success of this “New Economy”, where a noticeable rise in investment in information and communication technologies (ICT) was apparent, required individuals qualified not only to work with these technologies but also fit to answer the new organizational challenges brought about by them. Due to this, areas such as ICT and management began to become promoted more strongly, namely in higher education and research, and the connection between higher education and the job market strengthened.

An indirect discrimination of the humanities was thus induced, with real-world consequences. One of the symptoms relating to such a social phenomenon has been a progressively lower relative representation of graduates in humanities and, in some countries, also of the absolute representation, especially with regards to doctorate degrees. For instance, in the period between 2000 and 2012, while the number of humanities graduates rose by a factor of 1.4—and that of total graduates by a factor of 1.6 overall—those in the area of business administration increased by a factor of 1.8 Footnote 4 . For perspective, this accounts for virtually a fifth of total graduates. In other words, although academia within the humanities is growing, it is doing so at a disproportionately lower pace than when compared with other fields.

As Pierre Bourdieu had already outlined in Homo Academicvs (Bourdieu, 1984 ), alterations in the relative representation of students of certain areas, and thus of respective University staff, have an impact not only on power balances within the University, but also on its influence on society itself. The author saw these as morphological changes—a point of view that shapes the following considerations.

The impact of shrinking resources within academic departments of the humanities

With regard to the internal impact of shrinking resources within academic departments of the humanities, we can identify several clues as to how the University has generally been placing a lower importance on the humanities Footnote 5 :

Cuts in the financing of research and teaching;

a lower share of the space and structure within the University, through the elimination of courses and even departments;

undervalued human resources (fewer job offers, falling wages, overloaded work schedules, aging staff, lack of opportunities for the young);

a decrease in library resources and the like;

the use of evaluation methods typical of scientific activity and which are unadjusted to the specificity of the humanities, indirectly resulting in pressure to change communication practices specific to these fields and weakening their social impact;

the extent to which some fields in the humanities are weakened, reaching dimensions so residual that they become at risk of disappearing.

These phenomena, even when not simultaneous, contribute to paving the way to further devaluation as they ultimately work together to make the humanities look progressively less attractive. In an academic context we are essentially confronted with a vicious cycle of devaluation. The next two sections deal with a series of reasons for why it becomes urgent to break such a cycle.

If on the one hand we are witnessing a shrinking of resources within academic departments of the humanities, on the other we can see a clear reduction in the relative representation of humanities graduates entering the job market. Without going too much into detail on the interdependence between these two phenomena, they stand as symptoms of a clear loss of influence of the humanities on society itself – perhaps the result of a growing incomprehension of their usefulness. Indeed, the field appears to be held hostage to a way of appreciation that is overly focused on the economy, established by those who govern and apparently accepted by most of those governed. Governors in particular tend to have a peculiar, restricted and limited way of evaluating, classifying and neglecting the humanities, even if opinions amongst themselves are not always in agreement. Through this lens, the field can be pretentiously seen as a luxury, as economically irrelevant, or even as useless - worse still, as an obstacle to access the job market Footnote 6 .

These dynamics make it even more difficult for academics in the humanities to convince others of the relevance of their area. Therefore, when competing with other areas for resources, the overall trend has been to deprioritise the humanities.

In the above-mentioned report titled Towards Knowledge Societies , UNESCO recognized that political choices tend sometimes to place a high importance on specific disciplines, namely ‘at the expense of the humanities’ (UNESCO, 2005 , p. 90). These words are coated with a subtle yet sharp sense of loss. But what is in fact lost when the humanities see their presence in society diminished?

The benefits of studying the humanities

An analysis of several sources of information, such as surveys, studies and websites, has made it possible to understand the point of view of different social actors who believe there are advantages to graduating in the humanities (Costa, 2016 ). Students (Armitage et al., 2013 ), graduates (Lamb et al., 2012 ) and researchers (Levitt et al., 2010 ) in the humanities share their opinion on what the main advantages are, and their takes coincide with the way humanities courses are promoted on the websites of the universities that were taken into account in the analysis Footnote 7 . As it would turn out, these advantages match the profile of the ideal employee as outlined by a group of employers as a condition to achieve success at their companies, according to a separate study that is unrelated to the humanities in particular (Hart Research Associates, 2013 ). In other words, even neoliberal standards and concerns are adequately addressed.

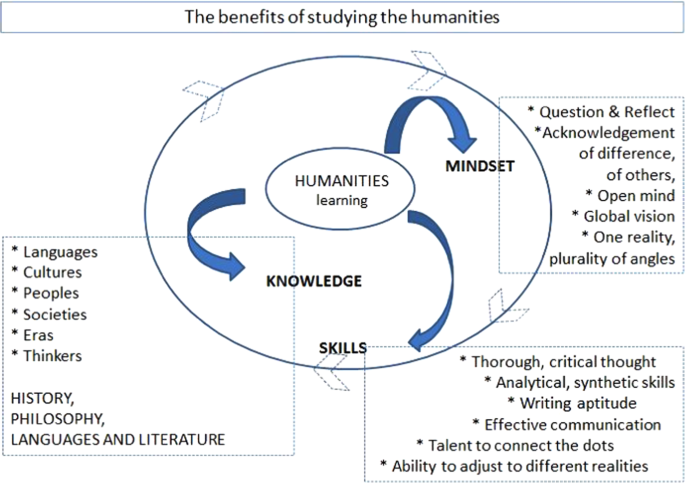

At its core, this acknowledgement of the value of the humanities can be looked at in three independent, mutually reinforcing levels: the comprehensive knowledge, skills and mindset that come with studying the field, and which are not easily outdated. These assets represent the genuine and specific character of studying these disciplines, and substantially differ from the priorities set by the political guidelines mentioned earlier. The following picture clarifies the scope of each of these levels (Fig. 1 ).

Benefits of studying the humanities. Source: adapted from Costa, 2017 , with permission of the Portuguese Association of Professionals in Sociology of Organizations and Work–APSIOT. The figure is not covered by the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International Licence

The attraction of studying the humanities lies precisely in that which one sets out to know and experiment with when one opts to study them. History, philosophy, languages and literature, to mention a few, are nuclear subjects that give us direct access to knowledge on that which is fundamentally and irreducibly human.

The challenge that this knowledge presents us with, and the effort of interpreting and attributing meaning to ourselves and that which surrounds us, are enhancers of the skills and mindset highlighted in the above graphic and their value is undeniable. Critical thought, acknowledgement of others, the ability to adjust to different realities and so forth are indispensable traits in any situation—in any institution, organization, government or company. It would thus follow that the humanities should be as explicitly and directly promoted by public policy as is specialized knowledge that directly serves firms and markets.

In spite of the value that can be recognized in studying the humanities, it stands that in the last few decades education in the field has been reduced to an almost insignificant dimension relative to other areas. It should be noted that demand in higher education is representative not just of the expectations of the students, or even of their educational and social backgrounds. It is also conditioned by the choices of a large group of social actors, interdependent amongst themselves Footnote 8 , such as decision makers – be it national or international, political or institutional –, employers and parents. But this depreciation has not been exclusive to higher education only. It has led to generalized deficits in knowledge, sensitivity and imagination, cognitive resources which are necessary to the acknowledgement of real problems within society and likewise to the development of possible solutions. The ability for citizens to possess and demonstrate a mindset of critical thinking has in this way been undermined.

One can thus argue that, at the very least from a social standpoint, much could be lost here. Martha Nussbaum warned in 2010 about the dangers this poses to democracy itself. The number of billionaires has nearly doubled as wealth has become even more concentrated in the last ten years since the financial crisis, worsening social inequalities (OXFAM, 2019 ). A society of consumption and uncontrolled, unregulated and acritical exploitation of natural resources is hindering sustainable development. Perhaps somewhat ironically, even the market economy registers some losses of its own in this scenario. The University of Oxford studied the career path of a group of their graduates in humanities, who had been students from 1960–1989, and subsequently produced a report that ‘shines a light on the breadth and variety of roles in society that they adopt, and the striking consistency with which they have had successful careers in sectors driving economic growth’ (Kreager, 2013 , p. 1). This conclusion contradicts the vision, or perhaps the bias, according to which graduations within the humanities are considered useless and of no value, especially for the economy and the labour market in general. The TED Talk Why tech needs the humanities Footnote 9 (December 2017) addresses this issue in the light yet personal manner of someone who has experienced it first hand.

On the complementarity of the various knowledge fields within society

In contrast to the trend within the humanities, from 2000 to 2012 and as previously mentioned, graduates in the area of business administration grew both in numbers and in relevance. Georges Corm ( 2013 ) considers that a new wave of employees, trained in accordance with the neoliberal ideas, has emerged in the job market. In his opinion, this is noticeable for instance in the case of MBAs, which in general have a similar format in use in the best schools around the world. Engwall et al. ( 2010 ) had already come to the conclusion that these graduates have become the new elite, taking up the leadership positions within organizations, replacing graduates namely in law and in engineering.

According to Colin Crouch ( 2016 ), ‘financial expertise has become the privileged form of knowledge, trumping other kinds, because it is embedded in the operation of […] the institutions that ensure profit maximization […]. Under certain conditions this dominance of financial knowledge can become self-destructive, destroying other forms of knowledge on which its own future depends’ (ibid., p. 34). Indeed, ‘serious problems arise when one kind of knowledge systematically triumphs over others’ (ibid., p. 35), a sentiment the author illustrates by giving examples related to engineering and geology. It can be argued that such a large pool of graduates and post-graduates in business administration has severely disrupted the balance and the complementarity of wisdom in society.

The environmental disasters and social crises that have marked the last decade, and which we have all witnessed, mean that the priority which had been given to some fields of knowledge is a concern not just of the academic community, but that it should instead be seen as an issue for all of society. If we start discrediting certain kinds of knowledge, we might end up discrediting all which are not in accordance with the interests that prevail in society at any given point in time, interests which in turn might not necessarily have the common good as their priority. This would be akin to opening a Pandora’s box.

Where has this led us? For instance, few of us are unaware of the difficulties that scientific evidence faces today in order to be appreciated and accepted by people who are farthest from the world of science, and who will more easily trust populist discourses (Baron, 2016 ; Boyd, 2016 ; Gluckman, 2017 ; Horton and Brown, 2018 ). Current disinvestment in the teachings of philosophy, particularly in the young, pulls us away from the basic foundations of knowledge and science, ultimately furthering the establishment of a post-truth society.

Concluding remarks

The process of devaluation of the humanities fortunately has not been enough to nullify the voice and ongoing work of their community. The World Humanities Conference, mentioned at the very beginning of this text, is a sign of the vitality and pertinence that this field still holds. When we look at the topics discussed at this conference, they are undoubtedly of great relevance for the society of today: ‘Humanity and the environment’; ‘Cultural identities, cultural diversities and intercultural relations: a global multicultural humanity’; ‘Borders and migrations’; ‘Heritage’; ‘History, memory and politics’; ‘The humanities in a changing world. What changes the world and in the world? What changes the humanities and in the humanities?’; and ‘Rebuilding the humanities, rebuilding humanism’. Events like this conference allow for the hope that a new and virtuous cycle for the humanities could be on the upswing for the benefit of all of society. One which will be more permeable and welcoming to all knowledge and skills, valuing all of its fields in a fair and impartial manner. Ultimately, the hope is to have a society that is zealous and proactive in the protection of a rich diversity of knowledge from the establishment and dominance of political hierarchies.

In: http://www.humanities2017.org/en .

Set of years for which OECD data are available in a usable way (verified in 23 May 2018 at OECD.Stat).

According to the ISCED 1997 (levels 5A and 6)—International Standard Classification of Education 1997 (first and second stages of tertiary education).

For this indicator, data for a subset of thirty OECD countries were used.

This systematization is based on the interpretation of a plurality of official statistics and reports on several countries (Costa, 2016 ).

Observations based on several publications, some of which are included in the bibliography (Benneworth and Jongbloed, 2010 ; Bod, 2011 ; Bok, 2007 ; Brinkley, 2009 ; Classen, 2012 ; Donoghue, 2010 ; European University Association, 2011 ; Fish, 2010 ; Gewirtz and Cribb, 2013 ; Gumport, 2000 ; Nussbaum, 2010 ; Weiland, 1992 ).

Harvard University ( http://artsandhumanities.fas.harvard.edu ), Stanford Humanities Center ( http://shc.stanford.edu/why-do-humanities-matter ), University of Chicago´s Master of Arts Program in the Humanities ( http://maph.uchicago.edu/directors ) and MIT School of Humanities, Arts, and Social Sciences ( http://shass.mit.edu/news/news-2014-power-of-humanities-arts-socialsciences-at-mit ). Data last updated from these websites: October 2015.

This statement is highly influenced by the thought of Norbert Elias, namely his concept of configuration (Elias, 2015 [1970]).

https://www.ted.com/talks/eric_berridge_why_tech_needs_the_humanities#t-7974 .

Altbach PG, Reisberg L, Rumbley LE (2009) Trends in global higher education: tracking an academic revolution. A report prepared for the UNESCO 2009 World Conference on Higher Education. UNESCO, Paris

Google Scholar

Armitage D et al. (2013) The teaching of the arts and humanities at Harvard College. Mapping the future. Harvard University, Cambridge

Baron N (2016) So you want to change the world? Nature 540:517–519

Article ADS CAS Google Scholar

Benneworth P, Jongbloed BW (2010) Who matters to universities? A stakeholder perspective on humanities, arts and social sciences valorisation. Higher Educ 59(5):567–588

Article Google Scholar

Bod R (2011) How the humanities changed the world: or why we should stop worrying and love the history of the humanities. Annuario 2011-2012–Unione Internazionale Degli Istituti Di Archeologia Storia E Storia dell’Arte in Roma 53:189–200

Bok D (2007, June 7) Remarks of President Derek Bok. Harvard Gazette . http://news.harvard.edu/gazette/story/2007/06/remarks-of-president-derek-bok/

Bourdieu P (1984) Homo academicvs. Minuit, Paris

Boyd IL (2016) Take the long view. Nature 540:520–521

Brinkley A (2009) The landscape of humanities research and funding. http://archive201406.humanitiesindicators.org/essays/brinkley.pdf

Classen A (2012) Humanities-to be or not to be, that is the question. Humanities 1:54–61

Corm G (2013) Le Nouveau Gouvernment du Monde. Idéologies, Structures, Contre-Pouvoirs. La Découverte, Paris

Costa RC (2016) A desvalorização das humanidades: universidade, transformações sociais e neoliberalismo. Doctoral Thesis: ISCTE-IUL, Lisboa, https://repositorio.iscte-iul.pt/bitstream/10071/12371/1/tese%20nova%20subcapa.pdf

Costa RC (2017) Novas políticas de ensino superior para a quarta Revolução Industrial. Um lugar para as Humanidades. In: XVII Encontro Nacional de SIOT. APSIOT: Lisboa. https://repositorio.iscte-iul.pt/bitstream/10071/16251/1/04_xvii_Ros%C3%A1rio_Couto_Costa.pdf

Crouch C (2016) The knowledge corrupters: hidden consequences of the financial takeover of public life. Polity Press, Cambridge

Donoghue F (2010, September 5) Can the Humanities Survive the 21st Century? The Chronicle of Higher Education . http://chronicle.com/article/Can-the-Humanities-Survive-the/124222/

Elias N (2015) Introdução à Sociologia. Edições70, Lisboa, [1970]

Engwall L, Kipping M, Usdiken B (2010) Public Science Systems, Higher Education, and the Trajectory of Academic Disciplines: Business Studies in the Unites States and Europe. In: Whitley R, Glässer J, Engwall L (eds) Reconfiguring Knowledge Production. Changing Authority Relationship in the Sciences and their Consequences for Intellectual Innovation. Oxford University, Oxford, p 325–353

European University Association (2011) Impact of the economic crisis on European Universities. EUA, Brussels

Fish S (2010, October 11) The crisis of the humanities officially arrives. The New York Times . http://www3.qcc.cuny.edu/WikiFiles/file/The%20Crisis%20of%20the%20Humanities%20Officially%20Arrives%20-%20NYTimes.com-1.pdf

Gewirtz S, Cribb A (2013) Representing 30 years of Higher Education Change: UK Universities and The Times Higher. J Educ Admin Hist 45(1):58–83

Gibbons M (1998) Higher education relevance in the 21st Century. World Bank, Washington, D.C

Gluckman P (2017) Scientific advice in a troubled world. The Office of the Prime Minister’s Science Advisory Committee, Wellington

Gumport PJ (2000) Academic restructuring: organizational change and institutional imperatives. Higher Educ 39:67–91

Hart Research Associates (2013) It takes More than a Major. Employer priorities for college learning and student success. Association of American Colleges and Universities, Washington, D.C

Heywood A (2014) Global politics. Palgrave Macmillan, London

Book Google Scholar

Horton P, Brown GW (2018) Integrating evidence, politics and society: a methodology for the science–policy interface. Pal Commun 4:42

Johnstone DB, Arora A, Experton W (1998) The financing and management of higher education. A status report on worldwide reforms. World Bank, Washington, DC

Kreager P (2013) Humanities graduates and the british economy. The hidden impact. University of Oxford, Oxford

Lamb H et al. (2012) Employability in the faculty of arts and social sciences. Final Report. CFE, Leicester

Levitt R et al. (2010) Assessing the impact of arts and humanities research at the University of Cambridge. Rand Corporation, Santa Monica, CA

Nussbaum MC (2010) Not for profit. Why democracy needs the humanities. Princeton University, Princeton

Peck J (2012) Neoliberalismo y crisis actual. Documentos y Aportes en Administración Pública y Gestión Estatal 12(19):7–27

OECD (2001) The new economy. Beyond the hype. Final Report on the OECD Growth Project. OECD, Paris

OXFAM (2019) Public good or private wealth? Oxfam GB, Oxford

UNESCO (2005) Towards knowledge societies. UNESCO, Paris

Weiland JS (1992) Humanities: introduction. In: Clark BR, Neave G (eds) The encyclopedia of higher education. Pergamon Press, Oxford, p 1981–1989

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Centre for Research and Studies in Sociology (CIES-IUL), University Institute of Lisbon (ISCTE-IUL), Lisbon, Portugal

Rosário Couto Costa

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Rosário Couto Costa .

Ethics declarations

Competing interests.

The author declares no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ .

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Costa, R.C. The place of the humanities in today’s knowledge society. Palgrave Commun 5 , 38 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-019-0245-6

Download citation

Received : 22 February 2018

Accepted : 25 March 2019

Published : 09 April 2019

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-019-0245-6

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

Quick links

- Explore articles by subject

- Guide to authors

- Editorial policies

New research shows how studying the humanities can benefit young people’s future careers and wider society

Studying a humanities degree at university gives young people vital skills which benefit them throughout their careers and prepare them for changes and uncertainty in the labour market, according to new research by Oxford University.

The report, called ‘The Value of the Humanities’, used an innovative methodology to understand how humanities graduates have fared over their whole careers – not just at a fixed point in time after graduation.

In the largest study of its kind, the report followed the career destinations of over 9,000 Oxford humanities graduates aged between 21 and 54 who entered the job market between 2000 and 2019, cross-referenced with UK government data on graduate outcomes and salaries. This was combined with in-depth interviews with around 100 alumni and current students, and interviews with employers from many sectors.

Further interviews with employers were carried out after the onset of COVID-19 and the impact it has had on the economy and the labour market to test how the report’s findings held up in a post-pandemic world. In fact, the report suggests that the pandemic has accelerated trends towards automation, digitalisation and flexible modes of working, and the resilience of humanities graduates makes them particularly well suited to navigate this changing environment. Recent developments in AI such as ChatGPT have only advanced predictions about imminent changes to the workplace brought by technology.

The report was commissioned by Oxford University’s Humanities Division and its lead author was Dr James Robson of the Oxford University’s Centre for Skills, Knowledge and Organisational Performance (SKOPE). It comes shortly after a report from the Higher Education Policy Institute which quantified the strength of the humanities in the UK.

Professor Dan Grimley, Head of Humanities at Oxford University, said: 'This report confirms what I and so many humanities graduates will already recognise: that the skills and experiences conferred by studying a humanities subject can transform their working life, their life as a whole, and the world around them.

'Students, graduates and employers noted that the resilience and adaptability developed during a humanities degree is particularly useful during big changes in the labour market – whether that’s triggered by a global financial crisis, changes caused by the rise of automation and AI technologies, or indeed a global pandemic.

'I often hear young people saying that they would love to continue studying music or languages or history or classics at A-level and beyond, but they fear it would compromise their ability to get an impactful job. I hope this report will convince them – and their parents and teachers – that they can continue studying the humanities subject they love and at the same time develop skills which employers report they are valuing more and more.'

Dame Emma Walmsley, CEO of GlaxoSmithKline who studied Classics and Modern Languages at Oxford, said: 'Being a humanities student at Oxford was foundational - to the curiosity, reserves of courage, and appetite for connectivity I have relied on deeply in life so far.'

The report’s key findings include:

1) Humanities graduates develop resilience, flexibility and skills to adapt to challenging and changing labour markets.

Employers interviewed for the report highlighted that disruption caused by COVID-19 and increased automation and digitisation will significantly change the nature of work in the next 5-10 years. The report said the “skills related to human interaction, communication and negotiation” learned while studying humanities will help them to meet future employer demands. This resilience helped graduates to cope and respond well to the impacts of the 2008 financial crisis. It seems set to have the same effect for graduates entering a post-COVID labour market characterised by increased digitalisation and remote working.

2) Humanities careers open a path to success in a wide range of employment sectors.

The business sector was the most common destination of humanities graduates (21%) over the period. 13% entered the legal profession and 13% went into the creative sector. There was a notable increase over time of graduates entering the ICT sector, particularly among women.

3) The skills developed by studying a humanities degree, such as communication, creativity and working in a team, are “highly valued and sought out by employers”.

Interviews with employers found they particularly valued the following traits in Humanities graduates:

- Critical thinking

- Strategic thinking

- An ability to synthesise and present complex information

- Empathy

- Creative problem-solving

This supports recent research by SKOPE and funded by the Arts & Humanities Research Council which revealed how business leaders in the UK see “narrative” as an integral part of doing business in the 21 st century. They found that being able to devise, craft and deliver a successful narrative is a “pre-requisite” for senior executives and becoming increasingly necessary for employees at all levels.

4) Humanities graduates benefit from subject-specific learning.

As well as the more transferrable skills like communication, graduates interviewed in the report showed that they draw throughout their careers on the sense of self-formation and the deep understanding they gain through studying histories, languages, cultures and literature on a humanities course.

5) Studying humanities helps graduates to make “wider contributions to society”.

Many interviewees in the report said their degree has enabled them to make an essential contribution to addressing the major issues facing humanity, and informed their sense of public mission and commitment. This includes navigating “fake news” and social media manipulation; climate change; energy needs; and the ethical implications of Artificial Intelligence.

6) Humanities graduates have high levels of job satisfaction and many said their primary motivation for studying their subject was not financial.

The report found that studying humanities subjects had a “transformative impact” on people’s identities and lives. Nonetheless, the average earnings of graduates assessed in the report were well above the national average, with History and Modern Languages graduates earning the most.

Dr James Robson and his co-authors for the report concluded: 'These findings clearly show that Oxford Humanities graduates are successful at navigating the labour market and financially rewarded, but also see value as existing beyond measurable returns and linked with knowledge, personal development, individual agency, and public goods.

'They highlight the need to take a more nuanced approach to analysing the value of degree subjects in order to take into account longer term career trajectories, individual agency within the labour market, the transformative power of knowledge, and broader public contributions of degrees within economic, social, and political discourses.'

The report makes recommendations to universities, employers and government to help young people make a transition into work:

- Offer support for a smooth transition into the workplace

- Provide internships, focused in particular on less advantaged students

- Support skills development in digital and working in a team, and provide students with insights into the changing labour market.

The full report can be found at:

pdf Value of Humanities report.pdf 1.77 MB

DISCOVER MORE

- Support Oxford's research

- Partner with Oxford on research

- Study at Oxford

- Research jobs at Oxford

You can view all news or browse by category

Ethics in the Humanities

- Living reference work entry

- First Online: 01 January 2015

- Cite this living reference work entry

- Cheryl K. Stenmark 2 &

- Nicolette A. Winn 2

1581 Accesses

2 Altmetric

Ethical behavior is critical in both academic and professional life. Because most professionals and academics work collaboratively with other people, it is important for them to behave ethically in order to develop quality collaborative relationships, so that they can trust each other. Because of the importance of ethical behavior in academic and professional settings, research and training programs aimed at improving ethical behavior, and the cognitive processes underlying ethical behavior are becoming increasingly widespread (National Institutes of Health 2002 ; Steneck 2002 ).

These research and training efforts have largely focused on professionals in the sciences and business. Ethical behavior, however, is important in any endeavor which involves multiple people working together. The Humanities have largely been ignored in explorations of ethical issues, particularly with regard to research ethics. This chapter argues that extending knowledge of ethical issues into the Humanities domain is important in order to identify the ethical problems faced by individuals in the Humanities, so that tailored research and training on these types of situations can help these individuals to deal with such problems.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this chapter

Institutional subscriptions

AAUP. (2009). Professional ethics . http://www.aaup.org/issues/professional-ethics . Retrieved 28 August 2014.

AHA. (2011). Statement on standards of professional conduct . http://www.historians.org/jobs-and-professional-development/statements-and-standards-of-the-profession/statement-on-standards-of-professional-conduct . Retrieved 28 August 2014.

AIA. (2012). 2010 code of ethics and professional conduct . http://www.aia.org/aiaucmp/groups/aia/documents/pdf/aiap074122.pdf . Retrieved 28 August 2014.

ASMP. (1993). Photographer’s code of conduct . http://ethics.iit.edu/ecodes/node/3666 . Retrieved 28 August 2014.

CAA. (2011). Standard and guidelines professional practices for artists . http://www.collegeart.org/guidelines/practice . Retrieved 28 August 2014.

De Vries, R., Anderson, M. S., & Martinson, B. C. (2006). Normal misbehavior: Scientists talk about the ethics of research. Journal of Empirical Research on Human Research Ethics, 1 , 43–50.

Article Google Scholar

Helton-Fauth, W., Gaddis, B., Scott, G., Mumford, M., Devenport, L., Connelly, S., & Brown, R. (2003). A new approach to assessing ethical conduct in scientific work. Accountability in Research, 10 , 205–228.

Kligyte, V., Marcy, R. T., Sevier, S. T., Godfrey, E. S., & Mumford, M. D. (2008). A qualitative approach to responsible conduct of research (RCR) training development: Identification of metacognitive strategies. Science and Engineering Ethics, 14 , 3–31.

Kuta, S. (2014). Philosophers call for profession-wide code of conduct . http://www.dailycamera.com/cu-news/ci_25331862/philosophers-call-profession-wide-code-conduct . Retrieved 28 August 2014.

Lewis, M. (2002). Doris Kearns Goodwin and the credibility gap. Forbes . http://www.forbes.com . Retrieved 28 August 2014.

MLA. (n.d.). Statement of professional ethics . http://www.mla.org/repview_profethics . Retrieved 28 August 2014.

Mumford, M. D., Connelly, M. S., Brown, R. P., Murphy, S. T., Hill, J. H., Antes, A. L., Waples, E. P., & Devenport, L. D. (2008). A sensemaking approach to ethics training for scientists: Preliminary evidence of training effectiveness. Ethics and Behavior, 18 (4), 315–399.

Mumford, M. D., Antes, A. L., Beeler, C., & Caughron, J. (2009). On the corruptions of scientists: The influence of field, environment, and personality. In R. J. Burke & C. L. Cooper (Eds.), Research companion to corruption in organization (pp. 145–170). Cheltenham: Edward Elgar.

Google Scholar

National Institutes of Health. (2002). Summary of the FY2010 President’s budget. http://officeofbudget.od.nih.gov/UI/2010/Summary%20of%20FY%202010%20President%27s%20Budget.pdf . Retrieved 3 June 2009.

New York Times. (2004). Ethical journalism a handbook of values and practices for the news and editorial departments . http://www.nytco.com/wp-content/uploads/NYT_Ethical_Journalism_0904-1.pdf . Retrieved 28 August 2014.

Ohiri, I. C. (2012). Promoting theatre business through good contacts and theatre business ethics. Insights to a Changing World Journal, 2 , 43–54.

Resnik, D. B. (2003). From Baltimore to Bell Labs: Reflections on two decades of debate about scientific misconduct. Accountability in Research, 10 , 123–135.

Sadri, H. (2012). Professional ethics in architecture and responsibilities of architects toward humanity. Turkish Journal of Business Ethics, 5 (9), 86.

Sekerka, L. E. (2009). Organizational ethics education and training: A review of best practices and their application. International Journal of Training and Development, 13 (2), 77–95.

Stanford Humanities Center. (2015). http://shc.stanford.edu/what-are-the-humanities . Retrieved 28 August 2014.

Steneck, N. H. (2002). ORI introduction to the responsible conduct of research . Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office.

Stenmark, C. K., Antes, A. L., Martin, L. E., Bagdasarov, Z., Johnson, J. F., Devenport, L. D., & Mumford, M. D. (2010). Ethics in the Humanities: Findings from focus groups. Journal of Academic Ethics, 8 , 285–300.

Thielke, J. (2009). A 1945 code of ethics for theatre workers emerges . http://lastagetimes.com/2009/08/a-1945-code-of-ethics-for-theatre-workers-surfaces/ . Retrieved 28 August 2014.

Waples, E. P., Antes, A. L., Murphy, S. T., Connelly, S., & Mumford, M. D. (2009). A meta-analytic investigation of business ethics instruction. Journal of Business Ethics, 87 (1), 133–151.

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Department of Psychology, Sociology, and Social Work, Angelo State University, 2601 W Avenue N, 76903, San Angelo, TX, USA

Cheryl K. Stenmark & Nicolette A. Winn

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Cheryl K. Stenmark .

Editor information

Editors and affiliations.

University of South Australia, Adelaide, South Australia, Australia

Tracey Ann Bretag

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

Copyright information

© 2015 Springer Science+Business Media Singapore

About this entry

Cite this entry.

Stenmark, C.K., Winn, N.A. (2015). Ethics in the Humanities. In: Bretag, T. (eds) Handbook of Academic Integrity. Springer, Singapore. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-287-079-7_43-1

Download citation

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-287-079-7_43-1

Received : 08 October 2014

Accepted : 22 April 2015

Published : 24 June 2015

Publisher Name : Springer, Singapore

Online ISBN : 978-981-287-079-7

eBook Packages : Springer Reference Education Reference Module Humanities and Social Sciences Reference Module Education

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

- Privacy Policy

Home » Humanities Research – Types, Methods and Examples

Humanities Research – Types, Methods and Examples

Table of Contents

Humanities Research

Definition:

Humanities research is a systematic and critical investigation of human culture, values, beliefs, and practices, including the study of literature, philosophy, history, art, languages, religion, and other aspects of human experience.

Types of Humanities Research

Types of Humanities Research are as follows:

Historical Research

This type of research involves studying the past to understand how societies and cultures have evolved over time. Historical research may involve examining primary sources such as documents, artifacts, and other cultural products, as well as secondary sources such as scholarly articles and books.

Cultural Studies

This type of research involves examining the cultural expressions and practices of a particular society or community. Cultural studies may involve analyzing literature, art, music, film, and other forms of cultural production to understand their social and cultural significance.

Linguistics Research

This type of research involves studying language and its role in shaping cultural and social practices. Linguistics research may involve analyzing the structure and use of language, as well as its historical development and cultural variations.

Anthropological Research

This type of research involves studying human cultures and societies from a comparative and cross-cultural perspective. Anthropological research may involve ethnographic fieldwork, participant observation, interviews, and other qualitative research methods.

Philosophy Research

This type of research involves examining fundamental questions about the nature of reality, knowledge, morality, and other philosophical concepts. Philosophy research may involve analyzing philosophical texts, conducting thought experiments, and engaging in philosophical discourse.

Art History Research

This type of research involves studying the history and significance of art and visual culture. Art history research may involve analyzing the formal and aesthetic qualities of art, as well as its historical context and cultural significance.

Literary Studies Research

This type of research involves analyzing literature and other forms of written expression. Literary studies research may involve examining the formal and structural qualities of literature, as well as its historical and cultural context.

Digital Humanities Research

This type of research involves using digital technologies to study and analyze cultural artifacts and practices. Digital humanities research may involve analyzing large datasets, creating digital archives, and using computational methods to study cultural phenomena.

Data Collection Methods

Data Collection Methods in Humanities Research are as follows:

- Interviews : This method involves conducting face-to-face, phone or virtual interviews with individuals who are knowledgeable about the research topic. Interviews may be structured, semi-structured, or unstructured, depending on the research questions and objectives. Interviews are often used in qualitative research to gain in-depth insights and perspectives.

- Surveys : This method involves distributing questionnaires or surveys to a sample of individuals or groups. Surveys may be conducted in person, through the mail, or online. Surveys are often used in quantitative research to collect data on attitudes, behaviors, and other characteristics of a population.

- Observations : This method involves observing and recording behavior or events in a natural or controlled setting. Observations may be structured or unstructured, and may involve the use of audio or video recording equipment. Observations are often used in qualitative research to collect data on social practices and behaviors.

- Archival Research: This method involves collecting data from historical documents, artifacts, and other cultural products. Archival research may involve accessing physical archives or online databases. Archival research is often used in historical and cultural studies to study the past.

- Case Studies : This method involves examining a single case or a small number of cases in depth. Case studies may involve collecting data through interviews, observations, and archival research. Case studies are often used in cultural studies, anthropology, and sociology to understand specific social or cultural phenomena.

- Focus Groups : This method involves bringing together a small group of individuals to discuss a particular topic or issue. Focus groups may be conducted in person or online, and are often used in qualitative research to gain insights into social and cultural practices and attitudes.

- Participatory Action Research : This method involves engaging with individuals or communities in the research process, with the goal of promoting social change or addressing a specific social problem. Participatory action research may involve conducting focus groups, interviews, or surveys, as well as involving participants in data analysis and interpretation.

Data Analysis Methods

Some common data analysis methods used in humanities research:

- Content Analysis : This method involves analyzing the content of texts or cultural artifacts to identify patterns, themes, and meanings. Content analysis is often used in literary studies, media studies, and cultural studies to analyze the meanings and representations conveyed in cultural products.

- Discourse Analysis: This method involves analyzing the use of language and discourse to understand social and cultural practices and identities. Discourse analysis may involve analyzing the structure, meaning, and power dynamics of language and discourse in different social contexts.

- Narrative Analysis: This method involves analyzing the structure, content, and meaning of narratives in different cultural contexts. Narrative analysis may involve analyzing the themes, symbols, and narrative devices used in literary texts or other cultural products.