- Grades 6-12

- School Leaders

NEW: Classroom Clean-Up/Set-Up Email Course! 🧽

Formative, Summative, and More Types of Assessments in Education

All the best ways to evaluate learning before, during, and after it happens.

When you hear the word assessment, do you automatically think “tests”? While it’s true that tests are one kind of assessment, they’re not the only way teachers evaluate student progress. Learn more about the types of assessments used in education, and find out how and when to use them.

Diagnostic Assessments

Formative assessments, summative assessments.

- Criterion-Referenced, Ipsative, and Normative Assessments

What is assessment?

In simplest terms, assessment means gathering data to help understand progress and effectiveness. In education, we gather data about student learning in variety of ways, then use it to assess both their progress and the effectiveness of our teaching programs. This helps educators know what’s working well and where they need to make changes.

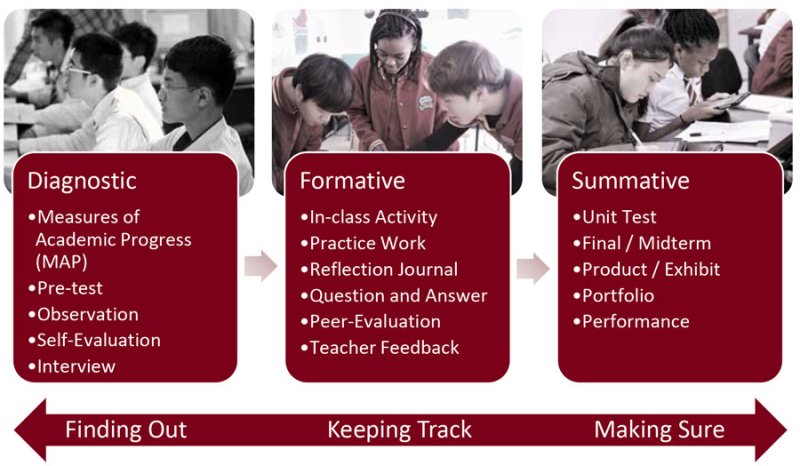

There are three broad types of assessments: diagnostic, formative, and summative. These take place throughout the learning process, helping students and teachers gauge learning. Within those three broad categories, you’ll find other types of assessment, such as ipsative, norm-referenced, and criterion-referenced.

What’s the purpose of assessment in education?

In education, we can group assessments under three main purposes:

- Of learning

- For learning

- As learning

Assessment of learning is student-based and one of the most familiar, encompassing tests, reports, essays, and other ways of determining what students have learned. These are usually summative assessments, and they are used to gauge progress for individuals and groups so educators can determine who has mastered the material and who needs more assistance.

When we talk about assessment for learning, we’re referring to the constant evaluations teachers perform as they teach. These quick assessments—such as in-class discussions or quick pop quizzes—give educators the chance to see if their teaching strategies are working. This allows them to make adjustments in action, tailoring their lessons and activities to student needs. Assessment for learning usually includes the formative and diagnostic types.

Assessment can also be a part of the learning process itself. When students use self-evaluations, flash cards, or rubrics, they’re using assessments to help them learn.

Let’s take a closer look at the various types of assessments used in education.

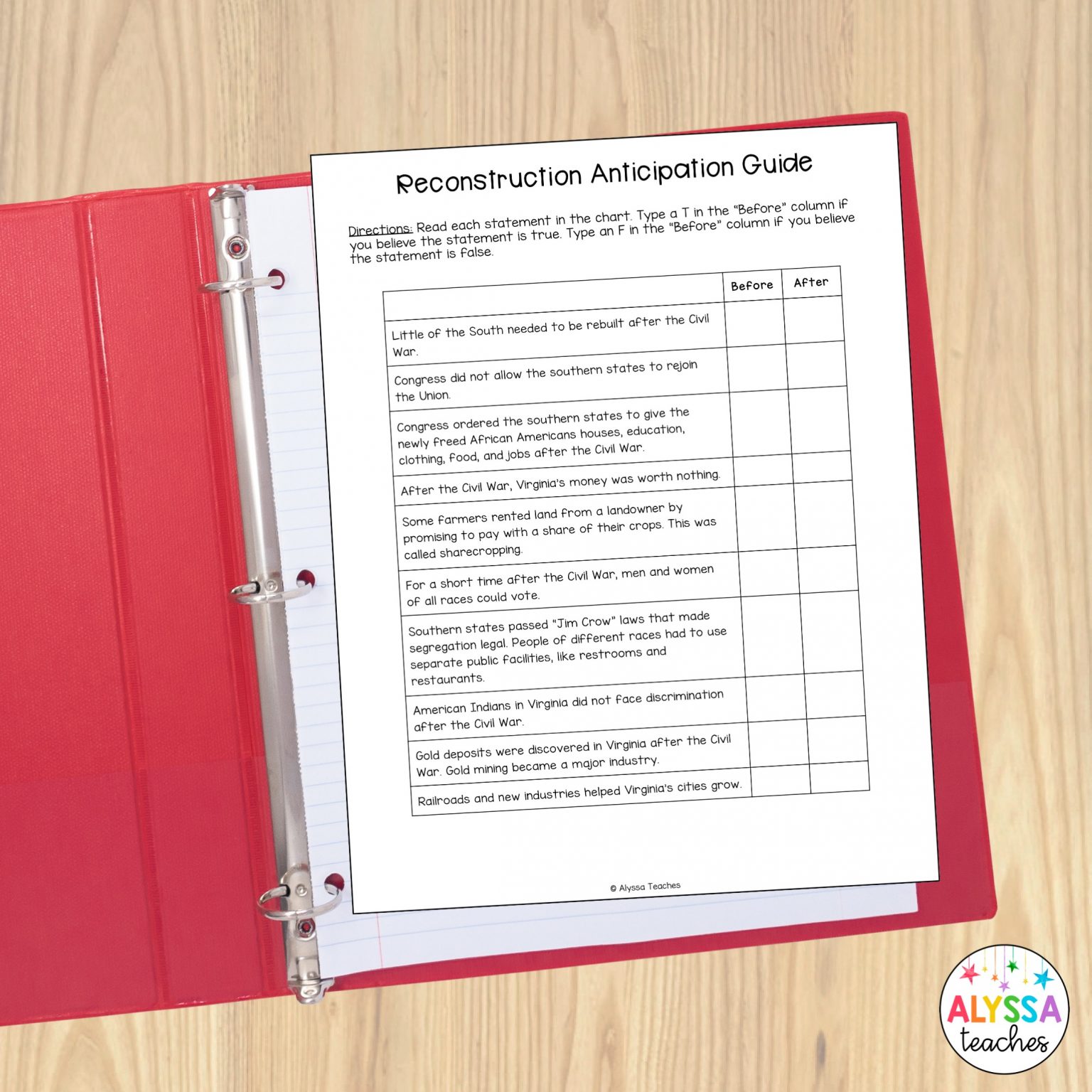

Diagnostic assessments are used before learning to determine what students already do and do not know. This often refers to pre-tests and other activities students attempt at the beginning of a unit.

How To Use Diagnostic Assessments

When giving diagnostic assessments, it’s important to remind students these won’t affect their overall grade. Instead, it’s a way for them to find out what they’ll be learning in an upcoming lesson or unit. It can also help them understand their own strengths and weaknesses, so they can ask for help when they need it.

Teachers can use results to understand what students already know and adapt their lesson plans accordingly. There’s no point in over-teaching a concept students have already mastered. On the other hand, a diagnostic assessment can also help highlight expected pre-knowledge that may be missing.

For instance, a teacher might assume students already know certain vocabulary words that are important for an upcoming lesson. If the diagnostic assessment indicates differently, the teacher knows they’ll need to take a step back and do a little pre-teaching before getting to their actual lesson plans.

Examples of Diagnostic Assessments

- Pre-test: This includes the same questions (or types of questions) that will appear on a final test, and it’s an excellent way to compare results.

- Blind Kahoot: Teachers and kids already love using Kahoot for test review, but it’s also the perfect way to introduce a new topic. Learn how Blind Kahoots work here.

- Survey or questionnaire: Ask students to rate their knowledge on a topic with a series of low-stakes questions.

- Checklist: Create a list of skills and knowledge students will build throughout a unit, and have them start by checking off any they already feel they’ve mastered. Revisit the list frequently as part of formative assessment.

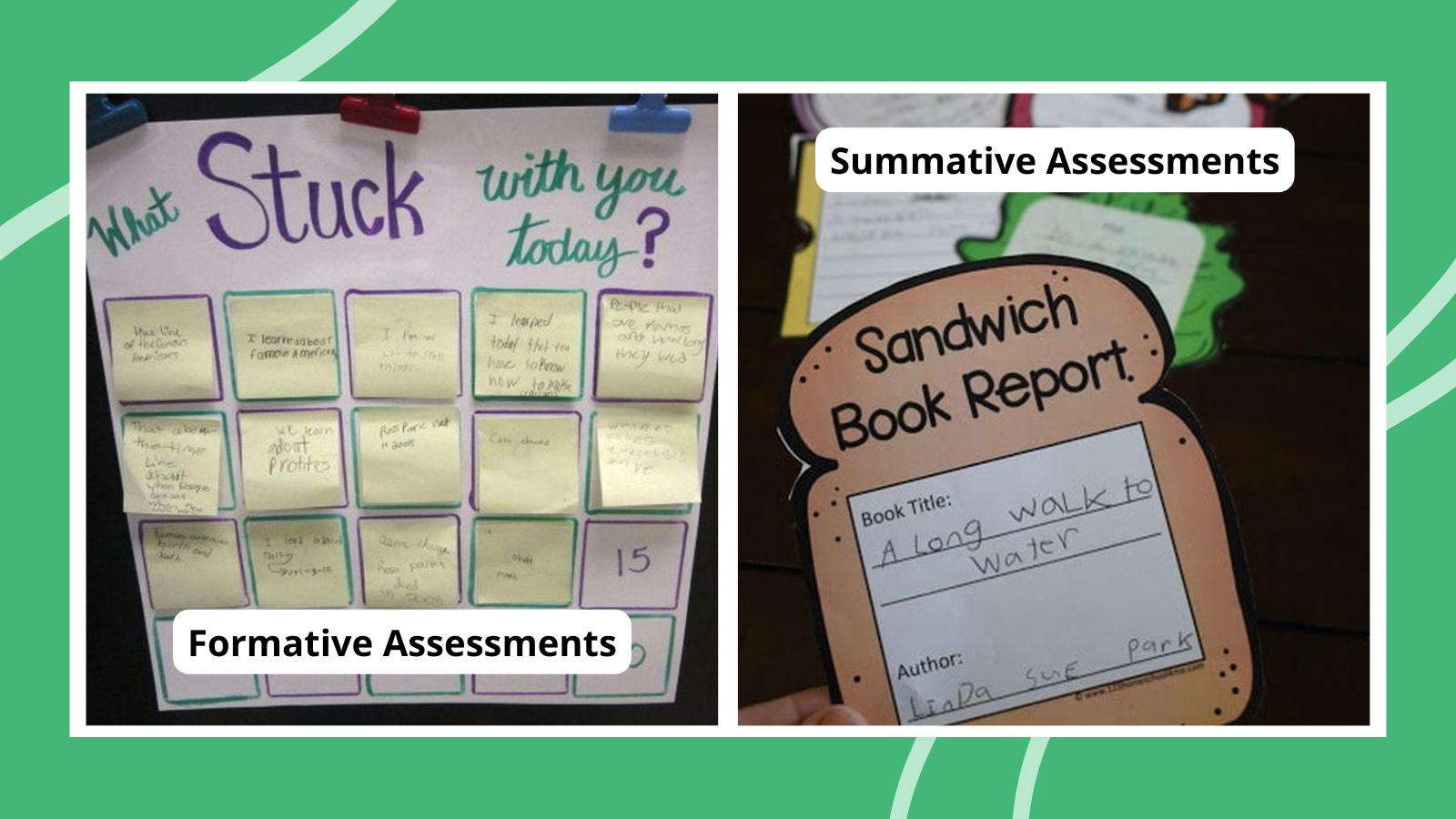

Formative assessments take place during instruction. They’re used throughout the learning process and help teachers make on-the-go adjustments to instruction and activities as needed. These assessments aren’t used in calculating student grades, but they are planned as part of a lesson or activity. Learn much more about formative assessments here.

How To Use Formative Assessments

As you’re building a lesson plan, be sure to include formative assessments at logical points. These types of assessments might be used at the end of a class period, after finishing a hands-on activity, or once you’re through with a unit section or learning objective.

Once you have the results, use that feedback to determine student progress, both overall and as individuals. If the majority of a class is struggling with a specific concept, you might need to find different ways to teach it. Or you might discover that one student is especially falling behind and arrange to offer extra assistance to help them out.

While kids may grumble, standard homework review assignments can actually be a pretty valuable type of formative assessment . They give kids a chance to practice, while teachers can evaluate their progress by checking the answers. Just remember that homework review assignments are only one type of formative assessment, and not all kids have access to a safe and dedicated learning space outside of school.

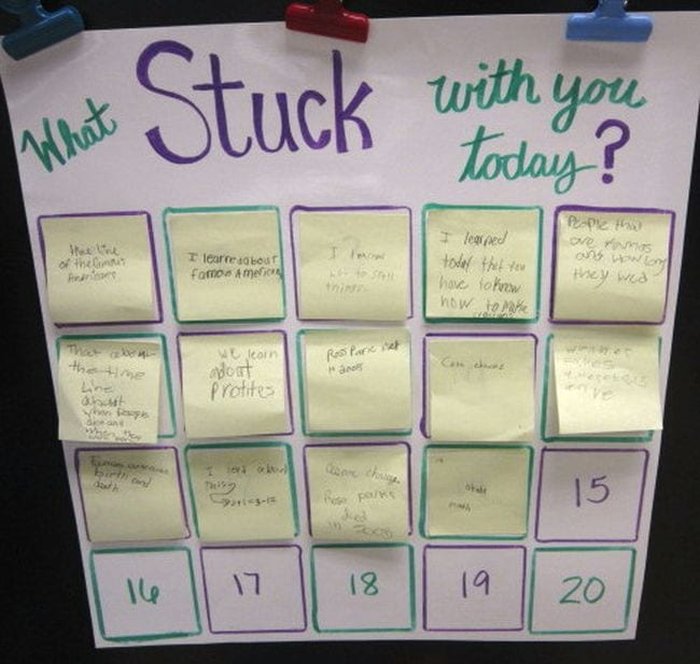

Examples of Formative Assessments

- Exit tickets : At the end of a lesson or class, pose a question for students to answer before they leave. They can answer using a sticky note, online form, or digital tool.

- Kahoot quizzes : Kids enjoy the gamified fun, while teachers appreciate the ability to analyze the data later to see which topics students understand well and which need more time.

- Flip (formerly Flipgrid): We love Flip for helping teachers connect with students who hate speaking up in class. This innovative (and free!) tech tool lets students post selfie videos in response to teacher prompts. Kids can view each other’s videos, commenting and continuing the conversation in a low-key way.

- Self-evaluation: Encourage students to use formative assessments to gauge their own progress too. If they struggle with review questions or example problems, they know they’ll need to spend more time studying. This way, they’re not surprised when they don’t do well on a more formal test.

Find a big list of 25 creative and effective formative assessment options here.

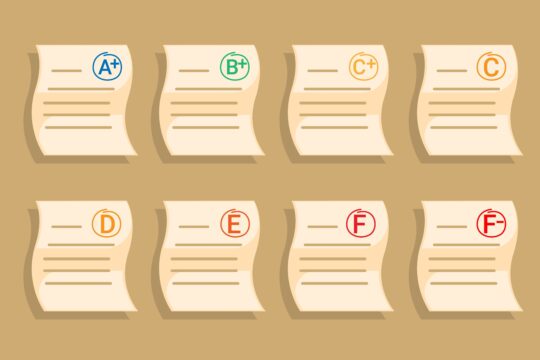

Summative assessments are used at the end of a unit or lesson to determine what students have learned. By comparing diagnostic and summative assessments, teachers and learners can get a clearer picture of how much progress they’ve made. Summative assessments are often tests or exams but also include options like essays, projects, and presentations.

How To Use Summative Assessments

The goal of a summative assessment is to find out what students have learned and if their learning matches the goals for a unit or activity. Ensure you match your test questions or assessment activities with specific learning objectives to make the best use of summative assessments.

When possible, use an array of summative assessment options to give all types of learners a chance to demonstrate their knowledge. For instance, some students suffer from severe test anxiety but may still have mastered the skills and concepts and just need another way to show their achievement. Consider ditching the test paper and having a conversation with the student about the topic instead, covering the same basic objectives but without the high-pressure test environment.

Summative assessments are often used for grades, but they’re really about so much more. Encourage students to revisit their tests and exams, finding the right answers to any they originally missed. Think about allowing retakes for those who show dedication to improving on their learning. Drive home the idea that learning is about more than just a grade on a report card.

Examples of Summative Assessments

- Traditional tests: These might include multiple-choice, matching, and short-answer questions.

- Essays and research papers: This is another traditional form of summative assessment, typically involving drafts (which are really formative assessments in disguise) and edits before a final copy.

- Presentations: From oral book reports to persuasive speeches and beyond, presentations are another time-honored form of summative assessment.

Find 25 of our favorite alternative assessments here.

More Types of Assessments

Now that you know the three basic types of assessments, let’s take a look at some of the more specific and advanced terms you’re likely to hear in professional development books and sessions. These assessments may fit into some or all of the broader categories, depending on how they’re used. Here’s what teachers need to know.

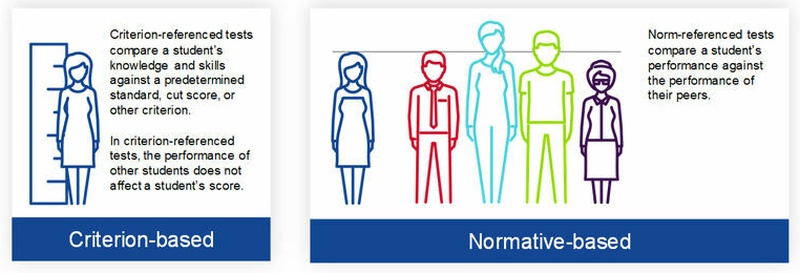

Criterion-Referenced Assessments

In this common type of assessment, a student’s knowledge is compared to a standard learning objective. Most summative assessments are designed to measure student mastery of specific learning objectives. The important thing to remember about this type of assessment is that it only compares a student to the expected learning objectives themselves, not to other students.

Many standardized tests are criterion-referenced assessments. A governing board determines the learning objectives for a specific group of students. Then, all students take a standardized test to see if they’ve achieved those objectives.

Find out more about criterion-referenced assessments here.

Norm-Referenced Assessments

These types of assessments do compare student achievement with that of their peers. Students receive a ranking based on their score and potentially on other factors as well. Norm-referenced assessments usually rank on a bell curve, establishing an “average” as well as high performers and low performers.

These assessments can be used as screening for those at risk for poor performance (such as those with learning disabilities) or to identify high-level learners who would thrive on additional challenges. They may also help rank students for college entrance or scholarships, or determine whether a student is ready for a new experience like preschool.

Learn more about norm-referenced assessments here.

Ipsative Assessments

In education, ipsative assessments compare a learner’s present performance to their own past performance, to chart achievement over time. Many educators consider ipsative assessment to be the most important of all , since it helps students and parents truly understand what they’ve accomplished—and sometimes, what they haven’t. It’s all about measuring personal growth.

Comparing the results of pre-tests with final exams is one type of ipsative assessment. Some schools use curriculum-based measurement to track ipsative performance. Kids take regular quick assessments (often weekly) to show their current skill/knowledge level in reading, writing, math, and other basics. Their results are charted, showing their progress over time.

Learn more about ipsative assessment in education here.

Have more questions about the best types of assessments to use with your students? Come ask for advice in the We Are Teachers HELPLINE group on Facebook.

Plus, check out creative ways to check for understanding ..

You Might Also Like

What Is Formative Assessment and How Should Teachers Use It?

Check student progress as they learn, and adapt to their needs. Continue Reading

Copyright © 2024. All rights reserved. 5335 Gate Parkway, Jacksonville, FL 32256

- Twitter Channel

- Facebook Profile

- YouTube Channel

- Instagram Profile

- Linkedin Profile

- Pinterest Profile

Classroom Assignments Matter. Here’s Why.

As a former classroom teacher, coach, and literacy specialist, I know the beginning of the school year demands that educators pay attention to a number of competing interests. Let me suggest one thing for teachers to focus on that, above all else, can close the student achievement gap: the rigor and quality of classroom assignments.

Digging into classroom assignments is revealing. It tells a story about curricula, instruction, achievement, and education equity. In the process, it uncovers what teachers believe about their students, what they know and understand about their standards and curricula, and what they are willing to do to advance student learning and achievement. So, when educators critically examine their own assignments (and the work students produce), they have an opportunity to gain powerful insight about teaching and learning — the kind of insight that can move the needle on student achievement. This type of analysis can identify trends across content areas such as English/language arts, science, social studies, and math.

At Ed Trust, we undertook such an analysis of 4,000 classroom assignments and found that students are being given in-school and out-of-school assignments that don’t align with grade-level standards, lack sufficient opportunities and time for writing, and include tasks that require low-level thinking and work production. We’ve seen assignments with little-to-no meaningful discussion and those with teachers over-supporting students, which effectively rob students of the kind of challenging thinking that leads to academic growth. And we’ve seen assignments where the reading looked like stop-and-go traffic, overrun with prescribed note-taking, breaking down students’ ability to build reading flow and deep learning.

These findings served as the basis for our second Equity in Motion convening. For three days this summer, educators from across the country explored the importance of regular and thoughtful assignment analysis. They found that carefully developed assignments have the power to make a curriculum last in students’ minds. They saw how assignments reveal whether students are grasping curricula, and if not, how teachers can adapt instruction. They also saw how assignments give clues into their own beliefs about students, which carry serious equity implications for all students, especially those who have been traditionally under-served. Throughout the convening, educators talked about the implications of their assignments and how assignments can affect overall achievement and address issues of equity. If assignments fall short of what standards demand, students will be ill-equipped to achieve at high levels.

The main take-away from this convening was simple but powerful: Assignments matter!

I encourage all teachers to take that message to heart. This school year, aim to make sure your assignments are more rigorous, standards-aligned, and authentically relevant to your students. Use our Literacy Analysis Assignment Guide to examine your assignments — alone, or better yet, with colleagues — to ensure you’re delivering assignments that propel your students to reach higher and achieve more. Doing this will provide a more complete picture of where your students are in their learning and how you can move them toward skill and concept mastery.

Remember this: Students can do no better than the assignments they receive.

Related Content

Common Questions About Automatic Enrollment Policies for Advanced Courses

What is automatic enrollment?Automatic enrollment is a policy that ensures all students who are ready for advanced courses have…

Statement by EdTrust Vice President of Partnerships and Engagement, Augustus Mays, on the 2024 Farm Bill

“Every day, more than 22 million households across the country depend on Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) benefits to…

Transfer Students Are Key to Building a More Diverse, Better Prepared Teacher Workforce

Leaders and advocates have focused on high teacher vacancy rates, but there’s no shortage of people who want to…

Marking the 70th Anniversary of Brown v. Board of Education and the Work that Remains

I grew up in the suburbs of Harrisburg, Pennsylvania, attending public schools that offered me a lot of opportunities:…

Why Districts Should Focus on High-Impact Tutoring Interventions as ESSER Funding Ends

ESSER dollars, or pandemic relief funds for schools, are running out at the end of September, and educators and…

Massachusetts Parents Concerned About Reading Approaches, Want Focus on Proven Methods

CONTACT: Chanthy [email protected](401) 497-4458In response to the literary crisis, parents want evidence-based reading instruction in schoolsBOSTON…

Hiding In Plain Sight: How Complex Decoding Challenges Can Block Comprehension for Older Readers

The news about American students’ reading abilities isn’t good: For far too long, our education system has failed to…

Testimony of Denise Forte on Senate FY25 Labor, Health and Human Services, Education and Related Agencies Appropriations Bill

Written Testimony for the Record (Download as a PDF)On behalf of Denise FortePresident and Chief Executive OfficerEdTrustBefore the Senate…

The State of Advanced Coursework in Washington

Washington has done exciting work in the past few years to broaden access to advanced coursework opportunities. The 2023…

Which Teacher Impacted You? We Asked, You Answered

We can all think back to an educator who ignited a love of learning in each of us. For…

Why I Teach, Where I Teach: To Ignite a Spark

Every child has a spark in them that can be lit through a high-quality public education, but not every…

Why I Teach, Where I Teach: To Build a Foundation for a Future

From a young age, I knew that I wanted to become a teacher. When I was eight years old,…

Types of Assignments and Assessments

Assignments and assessments are much the same thing: an instructor is unlikely to give students an assignment that does not receive some sort of assessment, whether formal or informal, formative or summative; and an assessment must be assigned, whether it is an essay, case study, or final exam. When the two terms are distinquished, "assignment" tends to refer to a learning activity that is primarily intended to foster or consolidate learning, while "assessment" tends to refer to an activity that is primarily intended to measure how well a student has learned.

In the list below, some attempt has been made to put the assignments/assessments in into logical categories. However, many of them could appear in multiple categories, so to prevent the list from becoming needlessly long, each item has been allocated to just one category.

Written Assignments:

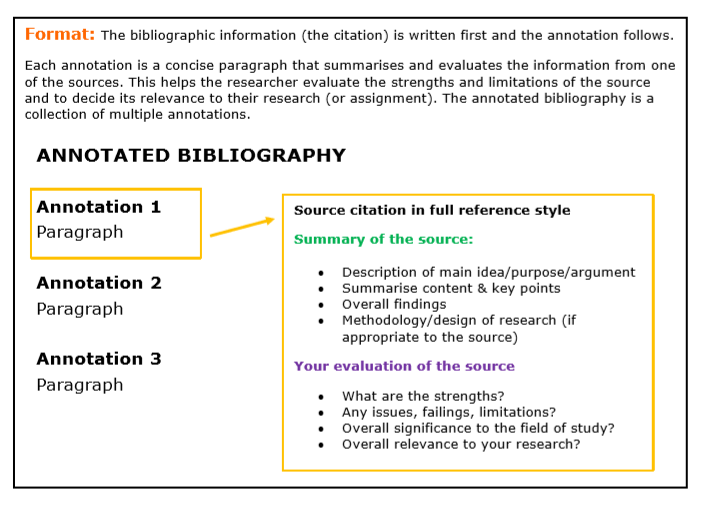

- Annotated Bibliography : An annotated bibliography is a list of citations or references to sources such as books, articles, websites, etc., along with brief descriptions or annotations that summarize, evaluate, and explain the content, relevance, and quality of each source. These annotations provide readers with insights into the source's content and its potential usefulness for research or reference.

- Summary/Abstract : A summary or abstract is a concise and condensed version of a longer document or research article, presenting the main points, key findings, and essential information in a clear and brief manner. It allows readers to quickly grasp the main ideas and determine whether the full document is relevant to their needs or interests. Abstracts are commonly found at the beginning of academic papers, research articles, and reports, providing a snapshot of the entire content.

- Case Analysis : Case analysis refers to a systematic examination and evaluation of a particular situation, problem, or scenario. It involves gathering relevant information, identifying key factors, analyzing various aspects, and formulating conclusions or recommendations based on the findings. Case analysis is commonly used in business, law, and other fields to make informed decisions and solve complex problems.

- Definition : A definition is a clear and concise explanation that describes the meaning of a specific term, concept, or object. It aims to provide a precise understanding of the item being defined, often by using words, phrases, or context that distinguish it from other similar or related things.

- Description of a Process : A description of a process is a step-by-step account or narrative that outlines the sequence of actions, tasks, or events involved in completing a particular activity or achieving a specific goal. Process descriptions are commonly used in various industries to document procedures, guide employees, and ensure consistent and efficient workflows.

- Executive Summary : An executive summary is a condensed version of a longer document or report that provides an overview of the main points, key findings, and major recommendations. It is typically aimed at busy executives or decision-makers who need a quick understanding of the content without delving into the full details. Executive summaries are commonly used in business proposals, project reports, and research papers to present essential information concisely.

- Proposal/Plan : A piece of writing that explains how a future problem or project will be approached.

- Laboratory or Field Notes: Laboratory/field notes are detailed and systematic written records taken by scientists, researchers, or students during experiments, observations, or fieldwork. These notes document the procedures, observations, data, and any unexpected findings encountered during the scientific investigation. They serve as a vital reference for later analysis, replication, and communication of the research process and results.

- Research Paper : A research paper is a more extensive and in-depth academic work that involves original research, data collection from multiple sources, and analysis. It aims to contribute new insights to the existing body of knowledge on a specific subject. Compare to "essay" below.

- Essay : A composition that calls for exposition of a thesis and is composed of several paragraphs including an introduction, a body, and a conclusion. It is different from a research paper in that the synthesis of bibliographic sources is not required. Compare to "Research Paper" above.

- Memo : A memo, short for memorandum, is a brief written message or communication used within an organization or business. It is often used to convey information, provide updates, make announcements, or request actions from colleagues or team members.

- Micro-theme : A micro-theme refers to a concise and focused piece of writing that addresses a specific topic or question. It is usually shorter than a traditional essay or research paper and requires the writer to present their ideas clearly and concisely.

- Notes on Reading : Notes on reading are annotations, comments, or summaries taken while reading a book, article, or any other written material. They serve as aids for understanding, retention, and later reference, helping the reader recall essential points and ideas from the text.

- Outline : An outline is a structured and organized plan that lays out the main points and structure of a written work, such as an essay, research paper, or presentation. It provides a roadmap for the writer, ensuring logical flow and coherence in the final piece.

- Plan for Conducting a Project : A plan for conducting a project outlines the steps, resources, timelines, and objectives for successfully completing a specific project. It includes details on how tasks will be executed and managed to achieve the desired outcomes.

- Poem : A poem is a literary work written in verse, using poetic devices like rhythm, rhyme, and imagery to convey emotions, ideas, and experiences.

- Play : A play is a form of literature written for performance, typically involving dialogue and actions by characters to tell a story or convey a message on stage.

- Choreography : Choreography refers to the art of designing dance sequences or movements, often for performances in various dance styles.

- Article/Book Review : An article or book review is a critical evaluation and analysis of a piece of writing, such as an article or a book. It typically includes a summary of the content and the reviewer's assessment of its strengths, weaknesses, and overall value.

- Review of Literature : A review of literature is a comprehensive summary and analysis of existing research and scholarly writings on a particular topic. It aims to provide an overview of the current state of knowledge in a specific field and may be a part of academic research or a standalone piece.

- Essay-based Exam : An essay-based exam is an assessment format where students are required to respond to questions or prompts with written, structured responses. It involves expressing ideas, arguments, and explanations in a coherent and organized manner, often requiring critical thinking and analysis.

- "Start" : In the context of academic writing, "start" refers to the initial phase of organizing and planning a piece of writing. It involves formulating a clear and focused thesis statement, which presents the main argument or central idea of the work, and creating an outline or list of ideas that will support and develop the thesis throughout the writing process.

- Statement of Assumptions : A statement of assumptions is a declaration or acknowledgment made at the beginning of a document or research paper, highlighting the underlying beliefs, conditions, or premises on which the work is based. It helps readers understand the foundation of the writer's perspective and the context in which the content is presented.

- Summary or Precis : A summary or precis is a concise and condensed version of a longer piece of writing, such as an article, book, or research paper. It captures the main points, key arguments, and essential information in a succinct manner, enabling readers to grasp the content without reading the full text.

- Unstructured Writing : Unstructured writing refers to the process of writing without following a specific plan, outline, or organizational structure. It allows the writer to freely explore ideas, thoughts, and creativity without the constraints of a predefined format or order. Unstructured writing is often used for brainstorming, creative expression, or personal reflection.

- Rough Draft or Freewrite : A rough draft or freewrite is an initial version of a piece of writing that is not polished or edited. It serves as an early attempt by the writer to get ideas on paper without worrying about perfection, allowing for exploration and creativity before revising and refining the final version.

- Technical or Scientific Report : A technical or scientific report is a document that presents detailed information about a specific technical or scientific project, research study, experiment, or investigation. It follows a structured format and includes sections like abstract, introduction, methods, results, discussion, and conclusion to communicate findings and insights in a clear and systematic manner.

- Journal article : A formal article reporting original research that could be submitted to an academic journal. Rather than a format dictated by the professor, the writer must use the conventional form of academic journals in the relevant discipline.

- Thesis statement : A clear and concise sentence or two that presents the main argument or central claim of an essay, research paper, or any written piece. It serves as a roadmap for the reader, outlining the writer's stance on the topic and the key points that will be discussed and supported in the rest of the work. The thesis statement provides focus and direction to the paper, guiding the writer's approach to the subject matter and helping to maintain coherence throughout the writing.

Visual Representation

- Brochure : A brochure is a printed or digital document used for advertising, providing information, or promoting a product, service, or event. It typically contains a combination of text and visuals, such as images or graphics, arranged in a visually appealing layout to convey a message effectively.

- Poster : A poster is a large printed visual display intended to catch the attention of an audience. It often contains a combination of text, images, and graphics to communicate information or promote a particular message, event, or cause.

- Chart : A chart is a visual representation of data or information using various formats such as pie charts, bar charts, line charts, or tables. It helps to illustrate relationships, trends, and comparisons in a concise and easy-to-understand manner.

- Graph : A graph is a visual representation of numerical data, usually presented using lines, bars, points, or other symbols on a coordinate plane. Graphs are commonly used to show trends, patterns, and relationships between variables.

- Concept Map : A concept map is a graphical tool used to organize and represent the connections and relationships between different concepts or ideas. It typically uses nodes or boxes to represent concepts and lines or arrows to show the connections or links between them, helping to visualize the relationships and hierarchy of ideas.

- Diagram : A diagram is a visual representation of a process, system, or structure using labeled symbols, shapes, or lines. Diagrams are used to explain complex concepts or procedures in a simplified and easy-to-understand manner.

- Table : A table is a systematic arrangement of data or information in rows and columns, allowing for easy comparison and reference. It is commonly used to present numerical data or detailed information in an organized format.

- Flowchart : A flowchart is a graphical representation of a process, workflow, or algorithm, using various shapes and arrows to show the sequence of steps or decisions involved. It helps visualize the logical flow and decision points, making it easier to understand and analyze complex processes.

- Multimedia or Slide Presentation : A multimedia or slide presentation is a visual communication tool that combines text, images, audio, video, and other media elements to deliver information or a message to an audience. It is often used for educational, business, or informational purposes and can be presented in person or virtually using software like Microsoft PowerPoint or Google Slides.

- ePortfolio : An ePortfolio, short for electronic portfolio, is a digital collection of an individual's work, accomplishments, skills, and reflections. It typically includes a variety of multimedia artifacts such as documents, presentations, videos, images, and links to showcase a person's academic, professional, or personal achievements. Eportfolios are used for self-reflection, professional development, and showcasing one's abilities to potential employers, educators, or peers. They provide a comprehensive and organized way to present evidence of learning, growth, and accomplishments over time.

Multiple-Choice Questions : These questions present a statement or question with several possible answer options, of which one or more may be correct. Test-takers must select the most appropriate choice(s). See CTE's Teaching Tip "Designing Multiple-Choice Questions."

True or False Questions : These questions require test-takers to determine whether a given statement is true or false based on their knowledge of the subject.

Short-Answer Questions : Test-takers are asked to provide brief written responses to questions or prompts. These responses are usually a few sentences or a paragraph in length.

Essay Questions : Essay questions require test-takers to provide longer, more detailed written responses to a specific topic or question. They may involve analysis, critical thinking, and the development of coherent arguments.

Matching Questions : In matching questions, test-takers are asked to pair related items from two lists. They must correctly match the items based on their associations.

Fill-in-the-Blank Questions : Test-takers must complete sentences or passages by filling in the missing words or phrases. This type of question tests recall and understanding of specific information.

Multiple-Response Questions : Similar to multiple-choice questions, but with multiple correct options. Test-takers must select all the correct choices to receive full credit.

Diagram or Image-Based Questions : These questions require test-takers to analyze or interpret diagrams, charts, graphs, or images to answer specific queries.

Problem-Solving Questions : These questions present real-world or theoretical problems that require test-takers to apply their knowledge and skills to arrive at a solution.

Vignettes or Case-Based Questions : In these questions, test-takers are presented with a scenario or case study and must analyze the information to answer related questions.

Sequencing or Order Questions : Test-takers are asked to arrange items or events in a particular order or sequence based on their understanding of the subject matter.

Projects intended for a specific audience :

- Advertisement : An advertisement is a promotional message or communication aimed at promoting a product, service, event, or idea to a target audience. It often uses persuasive techniques, visuals, and compelling language to attract attention and encourage consumers to take specific actions, such as making a purchase or seeking more information.

- Client Report for an Agency : A client report for an agency is a formal document prepared by a service provider or agency to communicate the results, progress, or recommendations of their work to their client. It typically includes an analysis of data, achievements, challenges, and future plans related to the project or services provided.

- News or Feature Story : A news story is a journalistic piece that reports on current events or recent developments, providing objective information in a factual and unbiased manner. A feature story, on the other hand, is a more in-depth and creative piece that explores human interest topics, profiles individuals, or delves into issues from a unique perspective.

- Instructional Manual : An instructional manual is a detailed document that provides step-by-step guidance, explanations, and procedures on how to use, assemble, operate, or perform specific tasks with a product or system. It aims to help users understand and utilize the item effectively and safely.

- Letter to the Editor : A letter to the editor is a written communication submitted by a reader to a newspaper, magazine, or online publication, expressing their opinion, feedback, or comments on a particular article, topic, or issue. It is intended for publication and allows individuals to share their perspectives with a broader audience.

Problem-Solving and Analysis :

- Taxonomy : Taxonomy is the science of classification, categorization, and naming of organisms, objects, or concepts based on their characteristics, similarities, and differences. It involves creating hierarchical systems that group related items together, facilitating organization and understanding within a particular domain.

- Budget with Rationale : A budget with rationale is a financial plan that outlines projected income and expenses for a specific period, such as a month or a year. The rationale provides explanations or justifications for each budget item, explaining the purpose and reasoning behind the allocated funds.

- Case Analysis : Case analysis refers to a methodical examination of a particular situation, scenario, or problem. It involves gathering relevant data, identifying key issues, analyzing different factors, and formulating conclusions or recommendations based on the findings. Case analysis is commonly used in various fields, such as business, law, and education, to make informed decisions and solve complex problems.

- Case Study : A case study is an in-depth analysis of a specific individual, group, organization, or situation. It involves thorough research, data collection, and detailed examination to understand the context, challenges, and outcomes associated with the subject of study. Case studies are widely used in academic research and professional contexts to gain insights into real-world scenarios.

- Word Problem : A word problem is a type of mathematical or logical question presented in a contextual format using words rather than purely numerical or symbolic representations. It challenges students to apply their knowledge and problem-solving skills to real-life situations.

Collaborative Activities

- Debate : A debate is a structured discussion between two or more individuals or teams with differing viewpoints on a specific topic or issue. Participants present arguments and counterarguments to support their positions, aiming to persuade the audience and ultimately reach a resolution or conclusion. Debates are commonly used in academic settings, public forums, and formal competitions to foster critical thinking, communication skills, and understanding of diverse perspectives.

- Group Discussion : A group discussion is an interactive conversation involving several individuals who come together to exchange ideas, opinions, and information on a particular subject. The discussion is typically moderated to ensure that everyone has an opportunity to participate, and it encourages active listening, collaboration, and problem-solving. Group discussions are commonly used in educational settings, team meetings, and decision-making processes to promote dialogue and collective decision-making.

- An oral report is a form of communication in which a person or group of persons present information, findings, or ideas verbally to an audience. It involves speaking in front of others, often in a formal setting, and delivering a structured presentation that may include visual aids, such as slides or props, to support the content. Oral reports are commonly used in academic settings, business environments, and various professional settings to share knowledge, research findings, project updates, or persuasive arguments. Effective oral reports require clear organization, articulation, and engaging delivery to effectively convey the intended message to the listeners.

Planning and Organization

- Inventory : An inventory involves systematically listing and categorizing items or resources to assess their availability, quantity, and condition. In an educational context, students might conduct an inventory of books in a library, equipment in a lab, or supplies in a classroom, enhancing their organizational and data collection skills.

- Materials and Methods Plan : A materials and methods plan involves developing a structured outline or description of the materials, tools, and procedures to be used in a specific experiment, research project, or practical task. It helps learners understand the importance of proper planning and documentation in scientific and research endeavors.

- Plan for Conducting a Project : This learning activity requires students to create a detailed roadmap for executing a project. It includes defining the project's objectives, identifying tasks and timelines, allocating resources, and setting milestones to monitor progress. It enhances students' project management and organizational abilities.

- Research Proposal Addressed to a Granting Agency : A formal document requesting financial support for a research project from a granting agency or organization. The proposal outlines the research questions, objectives, methodology, budget, and potential outcomes. It familiarizes learners with the process of seeking funding and strengthens their research and persuasive writing skills.

- Mathematical Problem : A mathematical problem is a task or question that requires the application of mathematical principles, formulas, or operations to find a solution. It could involve arithmetic, algebra, geometry, calculus, or other branches of mathematics, challenging individuals to solve the problem logically and accurately.

- Question : A question is a sentence or phrase used to elicit information, seek clarification, or provoke thought from someone else. Questions can be open-ended, closed-ended, or leading, depending on their purpose, and they play a crucial role in communication, problem-solving, and learning.

More Resources

CTE Teaching Tips

- Personal Response Systems

- Designing Multiple-Choice Questions

- Aligning Outcomes, Assessments, and Instruction

Other Resources

- Types of Assignments . University of Queensland.

If you would like support applying these tips to your own teaching, CTE staff members are here to help. View the CTE Support page to find the most relevant staff member to contact.

Catalog search

Teaching tip categories.

- Assessment and feedback

- Blended Learning and Educational Technologies

- Career Development

- Course Design

- Course Implementation

- Inclusive Teaching and Learning

- Learning activities

- Support for Student Learning

- Support for TAs

- Assessment and feedback ,

Teaching, Learning, & Professional Development Center

- Teaching Resources

- TLPDC Teaching Resources

How Do I Create Meaningful and Effective Assignments?

Prepared by allison boye, ph.d. teaching, learning, and professional development center.

Assessment is a necessary part of the teaching and learning process, helping us measure whether our students have really learned what we want them to learn. While exams and quizzes are certainly favorite and useful methods of assessment, out of class assignments (written or otherwise) can offer similar insights into our students' learning. And just as creating a reliable test takes thoughtfulness and skill, so does creating meaningful and effective assignments. Undoubtedly, many instructors have been on the receiving end of disappointing student work, left wondering what went wrong… and often, those problems can be remedied in the future by some simple fine-tuning of the original assignment. This paper will take a look at some important elements to consider when developing assignments, and offer some easy approaches to creating a valuable assessment experience for all involved.

First Things First…

Before assigning any major tasks to students, it is imperative that you first define a few things for yourself as the instructor:

- Your goals for the assignment . Why are you assigning this project, and what do you hope your students will gain from completing it? What knowledge, skills, and abilities do you aim to measure with this assignment? Creating assignments is a major part of overall course design, and every project you assign should clearly align with your goals for the course in general. For instance, if you want your students to demonstrate critical thinking, perhaps asking them to simply summarize an article is not the best match for that goal; a more appropriate option might be to ask for an analysis of a controversial issue in the discipline. Ultimately, the connection between the assignment and its purpose should be clear to both you and your students to ensure that it is fulfilling the desired goals and doesn't seem like “busy work.” For some ideas about what kinds of assignments match certain learning goals, take a look at this page from DePaul University's Teaching Commons.

- Have they experienced “socialization” in the culture of your discipline (Flaxman, 2005)? Are they familiar with any conventions you might want them to know? In other words, do they know the “language” of your discipline, generally accepted style guidelines, or research protocols?

- Do they know how to conduct research? Do they know the proper style format, documentation style, acceptable resources, etc.? Do they know how to use the library (Fitzpatrick, 1989) or evaluate resources?

- What kinds of writing or work have they previously engaged in? For instance, have they completed long, formal writing assignments or research projects before? Have they ever engaged in analysis, reflection, or argumentation? Have they completed group assignments before? Do they know how to write a literature review or scientific report?

In his book Engaging Ideas (1996), John Bean provides a great list of questions to help instructors focus on their main teaching goals when creating an assignment (p.78):

1. What are the main units/modules in my course?

2. What are my main learning objectives for each module and for the course?

3. What thinking skills am I trying to develop within each unit and throughout the course?

4. What are the most difficult aspects of my course for students?

5. If I could change my students' study habits, what would I most like to change?

6. What difference do I want my course to make in my students' lives?

What your students need to know

Once you have determined your own goals for the assignment and the levels of your students, you can begin creating your assignment. However, when introducing your assignment to your students, there are several things you will need to clearly outline for them in order to ensure the most successful assignments possible.

- First, you will need to articulate the purpose of the assignment . Even though you know why the assignment is important and what it is meant to accomplish, you cannot assume that your students will intuit that purpose. Your students will appreciate an understanding of how the assignment fits into the larger goals of the course and what they will learn from the process (Hass & Osborn, 2007). Being transparent with your students and explaining why you are asking them to complete a given assignment can ultimately help motivate them to complete the assignment more thoughtfully.

- If you are asking your students to complete a writing assignment, you should define for them the “rhetorical or cognitive mode/s” you want them to employ in their writing (Flaxman, 2005). In other words, use precise verbs that communicate whether you are asking them to analyze, argue, describe, inform, etc. (Verbs like “explore” or “comment on” can be too vague and cause confusion.) Provide them with a specific task to complete, such as a problem to solve, a question to answer, or an argument to support. For those who want assignments to lead to top-down, thesis-driven writing, John Bean (1996) suggests presenting a proposition that students must defend or refute, or a problem that demands a thesis answer.

- It is also a good idea to define the audience you want your students to address with their assignment, if possible – especially with writing assignments. Otherwise, students will address only the instructor, often assuming little requires explanation or development (Hedengren, 2004; MIT, 1999). Further, asking students to address the instructor, who typically knows more about the topic than the student, places the student in an unnatural rhetorical position. Instead, you might consider asking your students to prepare their assignments for alternative audiences such as other students who missed last week's classes, a group that opposes their position, or people reading a popular magazine or newspaper. In fact, a study by Bean (1996) indicated the students often appreciate and enjoy assignments that vary elements such as audience or rhetorical context, so don't be afraid to get creative!

- Obviously, you will also need to articulate clearly the logistics or “business aspects” of the assignment . In other words, be explicit with your students about required elements such as the format, length, documentation style, writing style (formal or informal?), and deadlines. One caveat, however: do not allow the logistics of the paper take precedence over the content in your assignment description; if you spend all of your time describing these things, students might suspect that is all you care about in their execution of the assignment.

- Finally, you should clarify your evaluation criteria for the assignment. What elements of content are most important? Will you grade holistically or weight features separately? How much weight will be given to individual elements, etc? Another precaution to take when defining requirements for your students is to take care that your instructions and rubric also do not overshadow the content; prescribing too rigidly each element of an assignment can limit students' freedom to explore and discover. According to Beth Finch Hedengren, “A good assignment provides the purpose and guidelines… without dictating exactly what to say” (2004, p. 27). If you decide to utilize a grading rubric, be sure to provide that to the students along with the assignment description, prior to their completion of the assignment.

A great way to get students engaged with an assignment and build buy-in is to encourage their collaboration on its design and/or on the grading criteria (Hudd, 2003). In his article “Conducting Writing Assignments,” Richard Leahy (2002) offers a few ideas for building in said collaboration:

• Ask the students to develop the grading scale themselves from scratch, starting with choosing the categories.

• Set the grading categories yourself, but ask the students to help write the descriptions.

• Draft the complete grading scale yourself, then give it to your students for review and suggestions.

A Few Do's and Don'ts…

Determining your goals for the assignment and its essential logistics is a good start to creating an effective assignment. However, there are a few more simple factors to consider in your final design. First, here are a few things you should do :

- Do provide detail in your assignment description . Research has shown that students frequently prefer some guiding constraints when completing assignments (Bean, 1996), and that more detail (within reason) can lead to more successful student responses. One idea is to provide students with physical assignment handouts , in addition to or instead of a simple description in a syllabus. This can meet the needs of concrete learners and give them something tangible to refer to. Likewise, it is often beneficial to make explicit for students the process or steps necessary to complete an assignment, given that students – especially younger ones – might need guidance in planning and time management (MIT, 1999).

- Do use open-ended questions. The most effective and challenging assignments focus on questions that lead students to thinking and explaining, rather than simple yes or no answers, whether explicitly part of the assignment description or in the brainstorming heuristics (Gardner, 2005).

- Do direct students to appropriate available resources . Giving students pointers about other venues for assistance can help them get started on the right track independently. These kinds of suggestions might include information about campus resources such as the University Writing Center or discipline-specific librarians, suggesting specific journals or books, or even sections of their textbook, or providing them with lists of research ideas or links to acceptable websites.

- Do consider providing models – both successful and unsuccessful models (Miller, 2007). These models could be provided by past students, or models you have created yourself. You could even ask students to evaluate the models themselves using the determined evaluation criteria, helping them to visualize the final product, think critically about how to complete the assignment, and ideally, recognize success in their own work.

- Do consider including a way for students to make the assignment their own. In their study, Hass and Osborn (2007) confirmed the importance of personal engagement for students when completing an assignment. Indeed, students will be more engaged in an assignment if it is personally meaningful, practical, or purposeful beyond the classroom. You might think of ways to encourage students to tap into their own experiences or curiosities, to solve or explore a real problem, or connect to the larger community. Offering variety in assignment selection can also help students feel more individualized, creative, and in control.

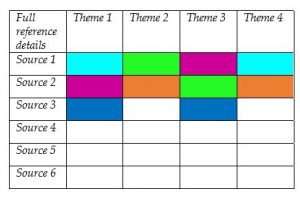

- If your assignment is substantial or long, do consider sequencing it. Far too often, assignments are given as one-shot final products that receive grades at the end of the semester, eternally abandoned by the student. By sequencing a large assignment, or essentially breaking it down into a systematic approach consisting of interconnected smaller elements (such as a project proposal, an annotated bibliography, or a rough draft, or a series of mini-assignments related to the longer assignment), you can encourage thoughtfulness, complexity, and thoroughness in your students, as well as emphasize process over final product.

Next are a few elements to avoid in your assignments:

- Do not ask too many questions in your assignment. In an effort to challenge students, instructors often err in the other direction, asking more questions than students can reasonably address in a single assignment without losing focus. Offering an overly specific “checklist” prompt often leads to externally organized papers, in which inexperienced students “slavishly follow the checklist instead of integrating their ideas into more organically-discovered structure” (Flaxman, 2005).

- Do not expect or suggest that there is an “ideal” response to the assignment. A common error for instructors is to dictate content of an assignment too rigidly, or to imply that there is a single correct response or a specific conclusion to reach, either explicitly or implicitly (Flaxman, 2005). Undoubtedly, students do not appreciate feeling as if they must read an instructor's mind to complete an assignment successfully, or that their own ideas have nowhere to go, and can lose motivation as a result. Similarly, avoid assignments that simply ask for regurgitation (Miller, 2007). Again, the best assignments invite students to engage in critical thinking, not just reproduce lectures or readings.

- Do not provide vague or confusing commands . Do students know what you mean when they are asked to “examine” or “discuss” a topic? Return to what you determined about your students' experiences and levels to help you decide what directions will make the most sense to them and what will require more explanation or guidance, and avoid verbiage that might confound them.

- Do not impose impossible time restraints or require the use of insufficient resources for completion of the assignment. For instance, if you are asking all of your students to use the same resource, ensure that there are enough copies available for all students to access – or at least put one copy on reserve in the library. Likewise, make sure that you are providing your students with ample time to locate resources and effectively complete the assignment (Fitzpatrick, 1989).

The assignments we give to students don't simply have to be research papers or reports. There are many options for effective yet creative ways to assess your students' learning! Here are just a few:

Journals, Posters, Portfolios, Letters, Brochures, Management plans, Editorials, Instruction Manuals, Imitations of a text, Case studies, Debates, News release, Dialogues, Videos, Collages, Plays, Power Point presentations

Ultimately, the success of student responses to an assignment often rests on the instructor's deliberate design of the assignment. By being purposeful and thoughtful from the beginning, you can ensure that your assignments will not only serve as effective assessment methods, but also engage and delight your students. If you would like further help in constructing or revising an assignment, the Teaching, Learning, and Professional Development Center is glad to offer individual consultations. In addition, look into some of the resources provided below.

Online Resources

“Creating Effective Assignments” http://www.unh.edu/teaching-excellence/resources/Assignments.htm This site, from the University of New Hampshire's Center for Excellence in Teaching and Learning, provides a brief overview of effective assignment design, with a focus on determining and communicating goals and expectations.

Gardner, T. (2005, June 12). Ten Tips for Designing Writing Assignments. Traci's Lists of Ten. http://www.tengrrl.com/tens/034.shtml This is a brief yet useful list of tips for assignment design, prepared by a writing teacher and curriculum developer for the National Council of Teachers of English . The website will also link you to several other lists of “ten tips” related to literacy pedagogy.

“How to Create Effective Assignments for College Students.” http:// tilt.colostate.edu/retreat/2011/zimmerman.pdf This PDF is a simplified bulleted list, prepared by Dr. Toni Zimmerman from Colorado State University, offering some helpful ideas for coming up with creative assignments.

“Learner-Centered Assessment” http://cte.uwaterloo.ca/teaching_resources/tips/learner_centered_assessment.html From the Centre for Teaching Excellence at the University of Waterloo, this is a short list of suggestions for the process of designing an assessment with your students' interests in mind. “Matching Learning Goals to Assignment Types.” http://teachingcommons.depaul.edu/How_to/design_assignments/assignments_learning_goals.html This is a great page from DePaul University's Teaching Commons, providing a chart that helps instructors match assignments with learning goals.

Additional References Bean, J.C. (1996). Engaging ideas: The professor's guide to integrating writing, critical thinking, and active learning in the classroom . San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Fitzpatrick, R. (1989). Research and writing assignments that reduce fear lead to better papers and more confident students. Writing Across the Curriculum , 3.2, pp. 15 – 24.

Flaxman, R. (2005). Creating meaningful writing assignments. The Teaching Exchange . Retrieved Jan. 9, 2008 from http://www.brown.edu/Administration/Sheridan_Center/pubs/teachingExchange/jan2005/01_flaxman.pdf

Hass, M. & Osborn, J. (2007, August 13). An emic view of student writing and the writing process. Across the Disciplines, 4.

Hedengren, B.F. (2004). A TA's guide to teaching writing in all disciplines . Boston: Bedford/St. Martin's.

Hudd, S. S. (2003, April). Syllabus under construction: Involving students in the creation of class assignments. Teaching Sociology , 31, pp. 195 – 202.

Leahy, R. (2002). Conducting writing assignments. College Teaching , 50.2, pp. 50 – 54.

Miller, H. (2007). Designing effective writing assignments. Teaching with writing . University of Minnesota Center for Writing. Retrieved Jan. 9, 2008, from http://writing.umn.edu/tww/assignments/designing.html

MIT Online Writing and Communication Center (1999). Creating Writing Assignments. Retrieved January 9, 2008 from http://web.mit.edu/writing/Faculty/createeffective.html .

Contact TTU

Eberly Center

Teaching excellence & educational innovation, creating assignments.

Here are some general suggestions and questions to consider when creating assignments. There are also many other resources in print and on the web that provide examples of interesting, discipline-specific assignment ideas.

Consider your learning objectives.

What do you want students to learn in your course? What could they do that would show you that they have learned it? To determine assignments that truly serve your course objectives, it is useful to write out your objectives in this form: I want my students to be able to ____. Use active, measurable verbs as you complete that sentence (e.g., compare theories, discuss ramifications, recommend strategies), and your learning objectives will point you towards suitable assignments.

Design assignments that are interesting and challenging.

This is the fun side of assignment design. Consider how to focus students’ thinking in ways that are creative, challenging, and motivating. Think beyond the conventional assignment type! For example, one American historian requires students to write diary entries for a hypothetical Nebraska farmwoman in the 1890s. By specifying that students’ diary entries must demonstrate the breadth of their historical knowledge (e.g., gender, economics, technology, diet, family structure), the instructor gets students to exercise their imaginations while also accomplishing the learning objectives of the course (Walvoord & Anderson, 1989, p. 25).

Double-check alignment.

After creating your assignments, go back to your learning objectives and make sure there is still a good match between what you want students to learn and what you are asking them to do. If you find a mismatch, you will need to adjust either the assignments or the learning objectives. For instance, if your goal is for students to be able to analyze and evaluate texts, but your assignments only ask them to summarize texts, you would need to add an analytical and evaluative dimension to some assignments or rethink your learning objectives.

Name assignments accurately.

Students can be misled by assignments that are named inappropriately. For example, if you want students to analyze a product’s strengths and weaknesses but you call the assignment a “product description,” students may focus all their energies on the descriptive, not the critical, elements of the task. Thus, it is important to ensure that the titles of your assignments communicate their intention accurately to students.

Consider sequencing.

Think about how to order your assignments so that they build skills in a logical sequence. Ideally, assignments that require the most synthesis of skills and knowledge should come later in the semester, preceded by smaller assignments that build these skills incrementally. For example, if an instructor’s final assignment is a research project that requires students to evaluate a technological solution to an environmental problem, earlier assignments should reinforce component skills, including the ability to identify and discuss key environmental issues, apply evaluative criteria, and find appropriate research sources.

Think about scheduling.

Consider your intended assignments in relation to the academic calendar and decide how they can be reasonably spaced throughout the semester, taking into account holidays and key campus events. Consider how long it will take students to complete all parts of the assignment (e.g., planning, library research, reading, coordinating groups, writing, integrating the contributions of team members, developing a presentation), and be sure to allow sufficient time between assignments.

Check feasibility.

Is the workload you have in mind reasonable for your students? Is the grading burden manageable for you? Sometimes there are ways to reduce workload (whether for you or for students) without compromising learning objectives. For example, if a primary objective in assigning a project is for students to identify an interesting engineering problem and do some preliminary research on it, it might be reasonable to require students to submit a project proposal and annotated bibliography rather than a fully developed report. If your learning objectives are clear, you will see where corners can be cut without sacrificing educational quality.

Articulate the task description clearly.

If an assignment is vague, students may interpret it any number of ways – and not necessarily how you intended. Thus, it is critical to clearly and unambiguously identify the task students are to do (e.g., design a website to help high school students locate environmental resources, create an annotated bibliography of readings on apartheid). It can be helpful to differentiate the central task (what students are supposed to produce) from other advice and information you provide in your assignment description.

Establish clear performance criteria.

Different instructors apply different criteria when grading student work, so it’s important that you clearly articulate to students what your criteria are. To do so, think about the best student work you have seen on similar tasks and try to identify the specific characteristics that made it excellent, such as clarity of thought, originality, logical organization, or use of a wide range of sources. Then identify the characteristics of the worst student work you have seen, such as shaky evidence, weak organizational structure, or lack of focus. Identifying these characteristics can help you consciously articulate the criteria you already apply. It is important to communicate these criteria to students, whether in your assignment description or as a separate rubric or scoring guide . Clearly articulated performance criteria can prevent unnecessary confusion about your expectations while also setting a high standard for students to meet.

Specify the intended audience.

Students make assumptions about the audience they are addressing in papers and presentations, which influences how they pitch their message. For example, students may assume that, since the instructor is their primary audience, they do not need to define discipline-specific terms or concepts. These assumptions may not match the instructor’s expectations. Thus, it is important on assignments to specify the intended audience http://wac.colostate.edu/intro/pop10e.cfm (e.g., undergraduates with no biology background, a potential funder who does not know engineering).

Specify the purpose of the assignment.

If students are unclear about the goals or purpose of the assignment, they may make unnecessary mistakes. For example, if students believe an assignment is focused on summarizing research as opposed to evaluating it, they may seriously miscalculate the task and put their energies in the wrong place. The same is true they think the goal of an economics problem set is to find the correct answer, rather than demonstrate a clear chain of economic reasoning. Consequently, it is important to make your objectives for the assignment clear to students.

Specify the parameters.

If you have specific parameters in mind for the assignment (e.g., length, size, formatting, citation conventions) you should be sure to specify them in your assignment description. Otherwise, students may misapply conventions and formats they learned in other courses that are not appropriate for yours.

A Checklist for Designing Assignments

Here is a set of questions you can ask yourself when creating an assignment.

- Provided a written description of the assignment (in the syllabus or in a separate document)?

- Specified the purpose of the assignment?

- Indicated the intended audience?

- Articulated the instructions in precise and unambiguous language?

- Provided information about the appropriate format and presentation (e.g., page length, typed, cover sheet, bibliography)?

- Indicated special instructions, such as a particular citation style or headings?

- Specified the due date and the consequences for missing it?

- Articulated performance criteria clearly?

- Indicated the assignment’s point value or percentage of the course grade?

- Provided students (where appropriate) with models or samples?

Adapted from the WAC Clearinghouse at http://wac.colostate.edu/intro/pop10e.cfm .

CONTACT US to talk with an Eberly colleague in person!

- Faculty Support

- Graduate Student Support

- Canvas @ Carnegie Mellon

- Quick Links

- Columbia University in the City of New York

- Office of Teaching, Learning, and Innovation

- University Policies

- Columbia Online

- Academic Calendar

- Resources and Technology

- Resources and Guides

Getting Started with Creative Assignments

Creative teaching and learning can be cultivated in any course context to increase student engagement and motivation, and promote thinking skills that are critical to problem-solving and innovation. This resource features examples of Columbia faculty who teach creatively and have reimagined their course assessments to allow students to demonstrate their learning in creative ways. Drawing on these examples, this resource provides suggestions for creating a classroom environment that supports student engagement in creative activities and assignments.

On this page:

- The What and Why of Creative Assignments

Examples of Creative Teaching and Learning at Columbia

- How To Get Started

Cite this resource: Columbia Center for Teaching and Learning (2022). Getting Started with Creative Assignments. Columbia University. Retrieved [today’s date] from https://ctl.columbia.edu/resources-and-technology/resources/creative-assignments/

The What and Why of Creative Assignments

Creative assignments encourage students to think in innovative ways as they demonstrate their learning. Thinking creatively involves combining or synthesizing information or course materials in new ways and is characterized by “a high degree of innovation, divergent thinking, and risk-taking” (AAC&U). It is associated with imagination and originality, and additional characteristics include: being open to new ideas and perspectives, believing alternatives exist, withholding judgment, generating multiple approaches to problems, and trying new ways to generate ideas (DiYanni, 2015: 41). Creative thinking is considered an important skill alongside critical thinking in tackling contemporary problems. Critical thinking allows students to evaluate the information presented to them while creative thinking is a process that allows students to generate new ideas and innovate.

Creative assignments can be integrated into any course regardless of discipline. Examples include the use of infographic assignments in Nursing (Chicca and Chunta, 2020) and Chemistry (Kothari, Castañeda, and McNeil, 2019); podcasting assignments in Social Work (Hitchcock, Sage & Sage, 2021); digital storytelling assignments in Psychology (Sheafer, 2017) and Sociology (Vaughn and Leon, 2021); and incorporating creative writing in the economics classroom (Davis, 2019) or reflective writing into Calculus assignment ( Gerstle, 2017) just to name a few. In a 2014 study, organic chemistry students who elected to begin their lab reports with a creative narrative were more excited to learn and earned better grades (Henry, Owens, and Tawney, 2015). In a public policy course, students who engaged in additional creative problem-solving exercises that included imaginative scenarios and alternative solution-finding showed greater interest in government reform and attentiveness to civic issues (Wukich and Siciliano, 2014).

The benefits of creative assignments include increased student engagement, motivation, and satisfaction (Snyder et al., 2013: 165); and furthered student learning of course content (Reynolds, Stevens, and West, 2013). These types of assignments promote innovation, academic integrity, student self-awareness/ metacognition (e.g., when students engage in reflection through journal assignments), and can be made authentic as students develop and apply skills to real-world situations.

When instructors give students open-ended assignments, they provide opportunities for students to think creatively as they work on a deliverable. They “unlock potential” (Ranjan & Gabora and Beghetto in Gregerson et al., 2013) for students to synthesize their knowledge and propose novel solutions. This promotes higher-level thinking as outlined in the revised Bloom’s Taxonomy’s “create” cognitive process category: “putting elements together to form a novel coherent whole or make an original product,” this involves generating ideas, planning, and producing something new.

The examples that follow highlight creative assignments in the Columbia University classroom. The featured Columbia faculty taught creatively – they tried new strategies, purposefully varied classroom activities and assessment modalities, and encouraged their students to take control of what and how they were learning (James & Brookfield, 2014: 66).

Dr. Cruz changed her course assessment by “moving away from high stakes assessments like a final paper or a final exam, to more open-ended and creative models of assessments.” Students were given the opportunity to synthesize their course learning, with options on topic and format of how to demonstrate their learning and to do so individually or in groups. They explored topics that were meaningful to them and related to the course material. Dr. Cruz noted that “This emphasis on playfulness and creativity led to fantastic final projects including a graphic novel interpretation, a video essay that applied critical theory to multiple texts, and an interactive virtual museum.” Students “took the opportunity to use their creative skills, or the skills they were interested in exploring because some of them had to develop new skills to produce these projects.” (Dr. Cruz; Dead Ideas in Teaching and Learning , Season 3, Episode 6). Along with their projects, students submitted an artist’s statement, where they had to explain and justify their choices.

Dr. Cruz noted that grading creative assignments require advanced planning. In her case, she worked closely with her TAs to develop a rubric that was shared with students in advance for full transparency and emphasized the importance of students connecting ideas to analytical arguments discussed in the class.

Watch Dr. Cruz’s 2021 Symposium presentation. Listen to Dr. Cruz talk about The Power of Blended Classrooms in Season 3, Episode 6 of the Dead Ideas in Teaching and Learning podcast. Get a glimpse into Dr. Cruz’s online classroom and her creative teaching and the design of learning experiences that enhanced critical thinking, creativity, curiosity, and community by viewing her Voices of Hybrid and Online Teaching and Learning submission.

As part of his standard practice, Dr. Yesilevskiy scaffolds assignments – from less complex to more complex – to ensure students integrate the concepts they learn in the class into their projects or new experiments. For example, in Laboratory 1, Dr. Yesilevskiy slowly increases the amount of independence in each experiment over the semester: students are given a full procedure in the first experiment and by course end, students are submitting new experiment proposals to Dr. Yesilevskiy for approval. This is creative thinking in action. Students not only learned how to “replicate existing experiments, but also to formulate and conduct new ones.”

Watch Dr. Yesilevskiy’s 2021 Symposium presentation.

How Do I Get Started?: Strategies to Support Creative Assignments

The previous section showcases examples of creative assignments in action at Columbia. To help you support such creative assignments in your classroom, this section details three strategies to support creative assignments and creative thinking. Firstly, re-consider the design of your assignments to optimize students’ creative output. Secondly, scaffold creative assignments using low-stakes classroom activities that build creative capacity. Finally, cultivate a classroom environment that supports creative thinking.

Design Considerations for Creative Assignments

Thoughtfully designed open-ended assignments and evaluation plans encourage students to demonstrate their learning in authentic ways. When designing creative assignments, consider the following suggestions for structuring and communicating to your students about the assignment.

Set clear expectations . Students may feel lost in the ambiguity and complexity of an open-ended assignment that requires them to create something new. Communicate the creative outcomes and learning objectives for the assignments (Ranjan & Gabora, 2013), and how students will be expected to draw on their learning in the course. Articulare how much flexibility and choice students have in determining what they work on and how they work on it. Share the criteria or a rubric that will be used to evaluate student deliverables. See the CTL’s resource Incorporating Rubrics Into Your Feedback and Grading Practices . If planning to evaluate creative thinking, consider adapting the American Association of Colleges and Universities’ creative thinking VALUE rubric .

Structure the project to sustain engagement and promote integrity. Consider how the project might be broken into smaller assignments that build upon each other and culminate in a synthesis project. The example presented above from Dr. Yesilevskiy’s teaching highlights how he scaffolded lab complexity, progressing from structured to student-driven. See the section below “Activities to Prepare Students for Creative Assignments” for sample activities to scaffold this work.

Create opportunities for ongoing feedback . Provide feedback at all phases of the assignment from idea inception through milestones to completion. Leverage office hours for individual or group conversations and feedback on project proposals, progress, and issues. See the CTL’s resource on Feedback for Learning . Consider creating opportunities for structured peer review for students to give each other feedback on their work. Students benefit from learning about their peers’ projects, and seeing different perspectives and approaches to accomplishing the open-ended assignment. See the CTL’s resource Peer Review: Intentional Design for Any Course Context .