- PRO Courses Guides New Tech Help Pro Expert Videos About wikiHow Pro Upgrade Sign In

- EDIT Edit this Article

- EXPLORE Tech Help Pro About Us Random Article Quizzes Request a New Article Community Dashboard This Or That Game Popular Categories Arts and Entertainment Artwork Books Movies Computers and Electronics Computers Phone Skills Technology Hacks Health Men's Health Mental Health Women's Health Relationships Dating Love Relationship Issues Hobbies and Crafts Crafts Drawing Games Education & Communication Communication Skills Personal Development Studying Personal Care and Style Fashion Hair Care Personal Hygiene Youth Personal Care School Stuff Dating All Categories Arts and Entertainment Finance and Business Home and Garden Relationship Quizzes Cars & Other Vehicles Food and Entertaining Personal Care and Style Sports and Fitness Computers and Electronics Health Pets and Animals Travel Education & Communication Hobbies and Crafts Philosophy and Religion Work World Family Life Holidays and Traditions Relationships Youth

- Browse Articles

- Learn Something New

- Quizzes Hot

- This Or That Game

- Train Your Brain

- Explore More

- Support wikiHow

- About wikiHow

- Log in / Sign up

- Education and Communications

How to Get Started With a Research Project

Last Updated: October 3, 2023 Fact Checked

This article was co-authored by Chris Hadley, PhD . Chris Hadley, PhD is part of the wikiHow team and works on content strategy and data and analytics. Chris Hadley earned his PhD in Cognitive Psychology from UCLA in 2006. Chris' academic research has been published in numerous scientific journals. This article has been fact-checked, ensuring the accuracy of any cited facts and confirming the authority of its sources. This article has been viewed 313,020 times.

You'll be required to undertake and complete research projects throughout your academic career and even, in many cases, as a member of the workforce. Don't worry if you feel stuck or intimidated by the idea of a research project, with care and dedication, you can get the project done well before the deadline!

Development and Foundation

- Don't hesitate while writing down ideas. You'll end up with some mental noise on the paper – silly or nonsensical phrases that your brain just pushes out. That's fine. Think of it as sweeping the cobwebs out of your attic. After a minute or two, better ideas will begin to form (and you might have a nice little laugh at your own expense in the meantime).

- Some instructors will even provide samples of previously successful topics if you ask for them. Just be careful that you don't end up stuck with an idea you want to do, but are afraid to do because you know someone else did it before.

- For example, if your research topic is “urban poverty,” you could look at that topic across ethnic or sexual lines, but you could also look into corporate wages, minimum wage laws, the cost of medical benefits, the loss of unskilled jobs in the urban core, and on and on. You could also try comparing and contrasting urban poverty with suburban or rural poverty, and examine things that might be different about both areas, such as diet and exercise levels, or air pollution.

- Think in terms of questions you want answered. A good research project should collect information for the purpose of answering (or at least attempting to answer) a question. As you review and interconnect topics, you'll think of questions that don't seem to have clear answers yet. These questions are your research topics.

- Don't limit yourself to libraries and online databases. Think in terms of outside resources as well: primary sources, government agencies, even educational TV programs. If you want to know about differences in animal population between public land and an Indian reservation, call the reservation and see if you can speak to their department of fish and wildlife.

- If you're planning to go ahead with original research, that's great – but those techniques aren't covered in this article. Instead, speak with qualified advisors and work with them to set up a thorough, controlled, repeatable process for gathering information.

- If your plan comes down to “researching the topic,” and there aren't any more specific things you can say about it, write down the types of sources you plan to use instead: books (library or private?), magazines (which ones?), interviews, and so on. Your preliminary research should have given you a solid idea of where to begin.

Expanding Your Idea with Research

- It's generally considered more convincing to source one item from three different authors who all agree on it than it is to rely too heavily on one book. Go for quantity at least as much as quality. Be sure to check citations, endnotes, and bibliographies to get more potential sources (and see whether or not all your authors are just quoting the same, older author).

- Writing down your sources and any other relevant details (such as context) around your pieces of information right now will save you lots of trouble in the future.

- Use many different queries to get the database results you want. If one phrasing or a particular set of words doesn't yield useful results, try rephrasing it or using synonymous terms. Online academic databases tend to be dumber than the sum of their parts, so you'll have to use tangentially related terms and inventive language to get all the results you want.

- If it's sensible, consider heading out into the field and speaking to ordinary people for their opinions. This isn't always appropriate (or welcomed) in a research project, but in some cases, it can provide you with some excellent perspective for your research.

- Review cultural artifacts as well. In many areas of study, there's useful information on attitudes, hopes, and/or concerns of people in a particular time and place contained within the art, music, and writing they produced. One has only to look at the woodblock prints of the later German Expressionists, for example, to understand that they lived in a world they felt was often dark, grotesque, and hopeless. Song lyrics and poetry can likewise express strong popular attitudes.

Expert Q&A

- Start early. The foundation of a great research project is the research, which takes time and patience to gather even if you aren't performing any original research of your own. Set aside time for it whenever you can, at least until your initial gathering phase is complete. Past that point, the project should practically come together on its own. Thanks Helpful 1 Not Helpful 0

- When in doubt, write more, rather than less. It's easier to pare down and reorganize an overabundance of information than it is to puff up a flimsy core of facts and anecdotes. Thanks Helpful 1 Not Helpful 0

- Respect the wishes of others. Unless you're a research journalist, it's vital that you yield to the wishes and requests of others before engaging in original research, even if it's technically ethical. Many older American Indians, for instance, harbor a great deal of cultural resentment towards social scientists who visit reservations for research, even those invited by tribal governments for important reasons such as language revitalization. Always tread softly whenever you're out of your element, and only work with those who want to work with you. Thanks Helpful 8 Not Helpful 2

- Be mindful of ethical concerns. Especially if you plan to use original research, there are very stringent ethical guidelines that must be followed for any credible academic body to accept it. Speak to an advisor (such as a professor) about what you plan to do and what steps you should take to verify that it will be ethical. Thanks Helpful 6 Not Helpful 2

You Might Also Like

- ↑ http://www.butte.edu/departments/cas/tipsheets/research/research_paper.html

- ↑ https://www.nhcc.edu/academics/library/doing-library-research/basic-steps-research-process

- ↑ https://library.sacredheart.edu/c.php?g=29803&p=185905

- ↑ https://owl.purdue.edu/owl/general_writing/common_writing_assignments/research_papers/choosing_a_topic.html

- ↑ https://www.unr.edu/writing-speaking-center/student-resources/writing-speaking-resources/using-an-interview-in-a-research-paper

- ↑ https://www.science.org/content/article/how-review-paper

About This Article

The easiest way to get started with a research project is to use your notes and other materials to come up with topics that interest you. Research your favorite topic to see if it can be developed, and then refine it into a research question. Begin thoroughly researching, and collect notes and sources. To learn more about finding reliable and helpful sources while you're researching, continue reading! Did this summary help you? Yes No

- Send fan mail to authors

Reader Success Stories

Jun 30, 2016

Did this article help you?

Maooz Asghar

Aug 14, 2016

Jun 27, 2016

Calvin Kiyondi

Apr 24, 2017

Nov 2, 2016

Featured Articles

Trending Articles

Watch Articles

- Terms of Use

- Privacy Policy

- Do Not Sell or Share My Info

- Not Selling Info

Don’t miss out! Sign up for

wikiHow’s newsletter

How to write a research plan: Step-by-step guide

Last updated

30 January 2024

Reviewed by

Short on time? Get an AI generated summary of this article instead

Today’s businesses and institutions rely on data and analytics to inform their product and service decisions. These metrics influence how organizations stay competitive and inspire innovation. However, gathering data and insights requires carefully constructed research, and every research project needs a roadmap. This is where a research plan comes into play.

Read this step-by-step guide for writing a detailed research plan that can apply to any project, whether it’s scientific, educational, or business-related.

- What is a research plan?

A research plan is a documented overview of a project in its entirety, from end to end. It details the research efforts, participants, and methods needed, along with any anticipated results. It also outlines the project’s goals and mission, creating layers of steps to achieve those goals within a specified timeline.

Without a research plan, you and your team are flying blind, potentially wasting time and resources to pursue research without structured guidance.

The principal investigator, or PI, is responsible for facilitating the research oversight. They will create the research plan and inform team members and stakeholders of every detail relating to the project. The PI will also use the research plan to inform decision-making throughout the project.

- Why do you need a research plan?

Create a research plan before starting any official research to maximize every effort in pursuing and collecting the research data. Crucially, the plan will model the activities needed at each phase of the research project .

Like any roadmap, a research plan serves as a valuable tool providing direction for those involved in the project—both internally and externally. It will keep you and your immediate team organized and task-focused while also providing necessary definitions and timelines so you can execute your project initiatives with full understanding and transparency.

External stakeholders appreciate a working research plan because it’s a great communication tool, documenting progress and changing dynamics as they arise. Any participants of your planned research sessions will be informed about the purpose of your study, while the exercises will be based on the key messaging outlined in the official plan.

Here are some of the benefits of creating a research plan document for every project:

Project organization and structure

Well-informed participants

All stakeholders and teams align in support of the project

Clearly defined project definitions and purposes

Distractions are eliminated, prioritizing task focus

Timely management of individual task schedules and roles

Costly reworks are avoided

- What should a research plan include?

The different aspects of your research plan will depend on the nature of the project. However, most official research plan documents will include the core elements below. Each aims to define the problem statement , devising an official plan for seeking a solution.

Specific project goals and individual objectives

Ideal strategies or methods for reaching those goals

Required resources

Descriptions of the target audience, sample sizes , demographics, and scopes

Key performance indicators (KPIs)

Project background

Research and testing support

Preliminary studies and progress reporting mechanisms

Cost estimates and change order processes

Depending on the research project’s size and scope, your research plan could be brief—perhaps only a few pages of documented plans. Alternatively, it could be a fully comprehensive report. Either way, it’s an essential first step in dictating your project’s facilitation in the most efficient and effective way.

- How to write a research plan for your project

When you start writing your research plan, aim to be detailed about each step, requirement, and idea. The more time you spend curating your research plan, the more precise your research execution efforts will be.

Account for every potential scenario, and be sure to address each and every aspect of the research.

Consider following this flow to develop a great research plan for your project:

Define your project’s purpose

Start by defining your project’s purpose. Identify what your project aims to accomplish and what you are researching. Remember to use clear language.

Thinking about the project’s purpose will help you set realistic goals and inform how you divide tasks and assign responsibilities. These individual tasks will be your stepping stones to reach your overarching goal.

Additionally, you’ll want to identify the specific problem, the usability metrics needed, and the intended solutions.

Know the following three things about your project’s purpose before you outline anything else:

What you’re doing

Why you’re doing it

What you expect from it

Identify individual objectives

With your overarching project objectives in place, you can identify any individual goals or steps needed to reach those objectives. Break them down into phases or steps. You can work backward from the project goal and identify every process required to facilitate it.

Be mindful to identify each unique task so that you can assign responsibilities to various team members. At this point in your research plan development, you’ll also want to assign priority to those smaller, more manageable steps and phases that require more immediate or dedicated attention.

Select research methods

Once you have outlined your goals, objectives, steps, and tasks, it’s time to drill down on selecting research methods . You’ll want to leverage specific research strategies and processes. When you know what methods will help you reach your goals, you and your teams will have direction to perform and execute your assigned tasks.

Research methods might include any of the following:

User interviews : this is a qualitative research method where researchers engage with participants in one-on-one or group conversations. The aim is to gather insights into their experiences, preferences, and opinions to uncover patterns, trends, and data.

Field studies : this approach allows for a contextual understanding of behaviors, interactions, and processes in real-world settings. It involves the researcher immersing themselves in the field, conducting observations, interviews, or experiments to gather in-depth insights.

Card sorting : participants categorize information by sorting content cards into groups based on their perceived similarities. You might use this process to gain insights into participants’ mental models and preferences when navigating or organizing information on websites, apps, or other systems.

Focus groups : use organized discussions among select groups of participants to provide relevant views and experiences about a particular topic.

Diary studies : ask participants to record their experiences, thoughts, and activities in a diary over a specified period. This method provides a deeper understanding of user experiences, uncovers patterns, and identifies areas for improvement.

Five-second testing: participants are shown a design, such as a web page or interface, for just five seconds. They then answer questions about their initial impressions and recall, allowing you to evaluate the design’s effectiveness.

Surveys : get feedback from participant groups with structured surveys. You can use online forms, telephone interviews, or paper questionnaires to reveal trends, patterns, and correlations.

Tree testing : tree testing involves researching web assets through the lens of findability and navigability. Participants are given a textual representation of the site’s hierarchy (the “tree”) and asked to locate specific information or complete tasks by selecting paths.

Usability testing : ask participants to interact with a product, website, or application to evaluate its ease of use. This method enables you to uncover areas for improvement in digital key feature functionality by observing participants using the product.

Live website testing: research and collect analytics that outlines the design, usability, and performance efficiencies of a website in real time.

There are no limits to the number of research methods you could use within your project. Just make sure your research methods help you determine the following:

What do you plan to do with the research findings?

What decisions will this research inform? How can your stakeholders leverage the research data and results?

Recruit participants and allocate tasks

Next, identify the participants needed to complete the research and the resources required to complete the tasks. Different people will be proficient at different tasks, and having a task allocation plan will allow everything to run smoothly.

Prepare a thorough project summary

Every well-designed research plan will feature a project summary. This official summary will guide your research alongside its communications or messaging. You’ll use the summary while recruiting participants and during stakeholder meetings. It can also be useful when conducting field studies.

Ensure this summary includes all the elements of your research project . Separate the steps into an easily explainable piece of text that includes the following:

An introduction: the message you’ll deliver to participants about the interview, pre-planned questioning, and testing tasks.

Interview questions: prepare questions you intend to ask participants as part of your research study, guiding the sessions from start to finish.

An exit message: draft messaging your teams will use to conclude testing or survey sessions. These should include the next steps and express gratitude for the participant’s time.

Create a realistic timeline

While your project might already have a deadline or a results timeline in place, you’ll need to consider the time needed to execute it effectively.

Realistically outline the time needed to properly execute each supporting phase of research and implementation. And, as you evaluate the necessary schedules, be sure to include additional time for achieving each milestone in case any changes or unexpected delays arise.

For this part of your research plan, you might find it helpful to create visuals to ensure your research team and stakeholders fully understand the information.

Determine how to present your results

A research plan must also describe how you intend to present your results. Depending on the nature of your project and its goals, you might dedicate one team member (the PI) or assume responsibility for communicating the findings yourself.

In this part of the research plan, you’ll articulate how you’ll share the results. Detail any materials you’ll use, such as:

Presentations and slides

A project report booklet

A project findings pamphlet

Documents with key takeaways and statistics

Graphic visuals to support your findings

- Format your research plan

As you create your research plan, you can enjoy a little creative freedom. A plan can assume many forms, so format it how you see fit. Determine the best layout based on your specific project, intended communications, and the preferences of your teams and stakeholders.

Find format inspiration among the following layouts:

Written outlines

Narrative storytelling

Visual mapping

Graphic timelines

Remember, the research plan format you choose will be subject to change and adaptation as your research and findings unfold. However, your final format should ideally outline questions, problems, opportunities, and expectations.

- Research plan example

Imagine you’ve been tasked with finding out how to get more customers to order takeout from an online food delivery platform. The goal is to improve satisfaction and retain existing customers. You set out to discover why more people aren’t ordering and what it is they do want to order or experience.

You identify the need for a research project that helps you understand what drives customer loyalty . But before you jump in and start calling past customers, you need to develop a research plan—the roadmap that provides focus, clarity, and realistic details to the project.

Here’s an example outline of a research plan you might put together:

Project title

Project members involved in the research plan

Purpose of the project (provide a summary of the research plan’s intent)

Objective 1 (provide a short description for each objective)

Objective 2

Objective 3

Proposed timeline

Audience (detail the group you want to research, such as customers or non-customers)

Budget (how much you think it might cost to do the research)

Risk factors/contingencies (any potential risk factors that may impact the project’s success)

Remember, your research plan doesn’t have to reinvent the wheel—it just needs to fit your project’s unique needs and aims.

Customizing a research plan template

Some companies offer research plan templates to help get you started. However, it may make more sense to develop your own customized plan template. Be sure to include the core elements of a great research plan with your template layout, including the following:

Introductions to participants and stakeholders

Background problems and needs statement

Significance, ethics, and purpose

Research methods, questions, and designs

Preliminary beliefs and expectations

Implications and intended outcomes

Realistic timelines for each phase

Conclusion and presentations

How many pages should a research plan be?

Generally, a research plan can vary in length between 500 to 1,500 words. This is roughly three pages of content. More substantial projects will be 2,000 to 3,500 words, taking up four to seven pages of planning documents.

What is the difference between a research plan and a research proposal?

A research plan is a roadmap to success for research teams. A research proposal, on the other hand, is a dissertation aimed at convincing or earning the support of others. Both are relevant in creating a guide to follow to complete a project goal.

What are the seven steps to developing a research plan?

While each research project is different, it’s best to follow these seven general steps to create your research plan:

Defining the problem

Identifying goals

Choosing research methods

Recruiting participants

Preparing the brief or summary

Establishing task timelines

Defining how you will present the findings

Should you be using a customer insights hub?

Do you want to discover previous research faster?

Do you share your research findings with others?

Do you analyze research data?

Start for free today, add your research, and get to key insights faster

Editor’s picks

Last updated: 18 April 2023

Last updated: 27 February 2023

Last updated: 6 February 2023

Last updated: 6 October 2023

Last updated: 5 February 2023

Last updated: 16 April 2023

Last updated: 7 March 2023

Last updated: 9 March 2023

Last updated: 12 December 2023

Last updated: 11 March 2024

Last updated: 6 March 2024

Last updated: 5 March 2024

Last updated: 13 May 2024

Latest articles

Related topics, .css-je19u9{-webkit-align-items:flex-end;-webkit-box-align:flex-end;-ms-flex-align:flex-end;align-items:flex-end;display:-webkit-box;display:-webkit-flex;display:-ms-flexbox;display:flex;-webkit-flex-direction:row;-ms-flex-direction:row;flex-direction:row;-webkit-box-flex-wrap:wrap;-webkit-flex-wrap:wrap;-ms-flex-wrap:wrap;flex-wrap:wrap;-webkit-box-pack:center;-ms-flex-pack:center;-webkit-justify-content:center;justify-content:center;row-gap:0;text-align:center;max-width:671px;}@media (max-width: 1079px){.css-je19u9{max-width:400px;}.css-je19u9>span{white-space:pre;}}@media (max-width: 799px){.css-je19u9{max-width:400px;}.css-je19u9>span{white-space:pre;}} decide what to .css-1kiodld{max-height:56px;display:-webkit-box;display:-webkit-flex;display:-ms-flexbox;display:flex;-webkit-align-items:center;-webkit-box-align:center;-ms-flex-align:center;align-items:center;}@media (max-width: 1079px){.css-1kiodld{display:none;}} build next, decide what to build next.

Users report unexpectedly high data usage, especially during streaming sessions.

Users find it hard to navigate from the home page to relevant playlists in the app.

It would be great to have a sleep timer feature, especially for bedtime listening.

I need better filters to find the songs or artists I’m looking for.

Log in or sign up

Get started for free

- Skip to main content

- Skip to primary sidebar

- Skip to footer

- QuestionPro

- Solutions Industries Gaming Automotive Sports and events Education Government Travel & Hospitality Financial Services Healthcare Cannabis Technology Use Case NPS+ Communities Audience Contactless surveys Mobile LivePolls Member Experience GDPR Positive People Science 360 Feedback Surveys

- Resources Blog eBooks Survey Templates Case Studies Training Help center

Home Market Research Research Tools and Apps

Research Process Steps: What they are + How To Follow

There are various approaches to conducting basic and applied research. This article explains the research process steps you should know. Whether you are doing basic research or applied research, there are many ways of doing it. In some ways, each research study is unique since it is conducted at a different time and place.

Conducting research might be difficult, but there are clear processes to follow. The research process starts with a broad idea for a topic. This article will assist you through the research process steps, helping you focus and develop your topic.

Research Process Steps

The research process consists of a series of systematic procedures that a researcher must go through in order to generate knowledge that will be considered valuable by the project and focus on the relevant topic.

To conduct effective research, you must understand the research process steps and follow them. Here are a few steps in the research process to make it easier for you:

Step 1: Identify the Problem

Finding an issue or formulating a research question is the first step. A well-defined research problem will guide the researcher through all stages of the research process, from setting objectives to choosing a technique. There are a number of approaches to get insight into a topic and gain a better understanding of it. Such as:

- A preliminary survey

- Case studies

- Interviews with a small group of people

- Observational survey

Step 2: Evaluate the Literature

A thorough examination of the relevant studies is essential to the research process . It enables the researcher to identify the precise aspects of the problem. Once a problem has been found, the investigator or researcher needs to find out more about it.

This stage gives problem-zone background. It teaches the investigator about previous research, how they were conducted, and its conclusions. The researcher can build consistency between his work and others through a literature review. Such a review exposes the researcher to a more significant body of knowledge and helps him follow the research process efficiently.

Step 3: Create Hypotheses

Formulating an original hypothesis is the next logical step after narrowing down the research topic and defining it. A belief solves logical relationships between variables. In order to establish a hypothesis, a researcher must have a certain amount of expertise in the field.

It is important for researchers to keep in mind while formulating a hypothesis that it must be based on the research topic. Researchers are able to concentrate their efforts and stay committed to their objectives when they develop theories to guide their work.

Step 4: The Research Design

Research design is the plan for achieving objectives and answering research questions. It outlines how to get the relevant information. Its goal is to design research to test hypotheses, address the research questions, and provide decision-making insights.

The research design aims to minimize the time, money, and effort required to acquire meaningful evidence. This plan fits into four categories:

- Exploration and Surveys

- Data Analysis

- Observation

Step 5: Describe Population

Research projects usually look at a specific group of people, facilities, or how technology is used in the business. In research, the term population refers to this study group. The research topic and purpose help determine the study group.

Suppose a researcher wishes to investigate a certain group of people in the community. In that case, the research could target a specific age group, males or females, a geographic location, or an ethnic group. A final step in a study’s design is to specify its sample or population so that the results may be generalized.

Step 6: Data Collection

Data collection is important in obtaining the knowledge or information required to answer the research issue. Every research collected data, either from the literature or the people being studied. Data must be collected from the two categories of researchers. These sources may provide primary data.

- Questionnaire

Secondary data categories are:

- Literature survey

- Official, unofficial reports

- An approach based on library resources

Step 7: Data Analysis

During research design, the researcher plans data analysis. After collecting data, the researcher analyzes it. The data is examined based on the approach in this step. The research findings are reviewed and reported.

Data analysis involves a number of closely related stages, such as setting up categories, applying these categories to raw data through coding and tabulation, and then drawing statistical conclusions. The researcher can examine the acquired data using a variety of statistical methods.

Step 8: The Report-writing

After completing these steps, the researcher must prepare a report detailing his findings. The report must be carefully composed with the following in mind:

- The Layout: On the first page, the title, date, acknowledgments, and preface should be on the report. A table of contents should be followed by a list of tables, graphs, and charts if any.

- Introduction: It should state the research’s purpose and methods. This section should include the study’s scope and limits.

- Summary of Findings: A non-technical summary of findings and recommendations will follow the introduction. The findings should be summarized if they’re lengthy.

- Principal Report: The main body of the report should make sense and be broken up into sections that are easy to understand.

- Conclusion: The researcher should restate his findings at the end of the main text. It’s the final result.

LEARN ABOUT: 12 Best Tools for Researchers

The research process involves several steps that make it easy to complete the research successfully. The steps in the research process described above depend on each other, and the order must be kept. So, if we want to do a research project, we should follow the research process steps.

QuestionPro’s enterprise-grade research platform can collect survey and qualitative observation data. The tool’s nature allows for data processing and essential decisions. The platform lets you store and process data. Start immediately!

LEARN MORE FREE TRIAL

MORE LIKE THIS

Zero Correlation: Definition, Examples + How to Determine It

Jul 1, 2024

When You Have Something Important to Say, You want to Shout it From the Rooftops

Jun 28, 2024

The Item I Failed to Leave Behind — Tuesday CX Thoughts

Jun 25, 2024

Feedback Loop: What It Is, Types & How It Works?

Jun 21, 2024

Other categories

- Academic Research

- Artificial Intelligence

- Assessments

- Brand Awareness

- Case Studies

- Communities

- Consumer Insights

- Customer effort score

- Customer Engagement

- Customer Experience

- Customer Loyalty

- Customer Research

- Customer Satisfaction

- Employee Benefits

- Employee Engagement

- Employee Retention

- Friday Five

- General Data Protection Regulation

- Insights Hub

- Life@QuestionPro

- Market Research

- Mobile diaries

- Mobile Surveys

- New Features

- Online Communities

- Question Types

- QuestionPro Products

- Release Notes

- Research Tools and Apps

- Revenue at Risk

- Survey Templates

- Training Tips

- Tuesday CX Thoughts (TCXT)

- Uncategorized

- Video Learning Series

- What’s Coming Up

- Workforce Intelligence

- About University of Sheffield

- Campus life

- Accommodation

- Student support

- International Foundation Year

- Pre-Masters

- Pre-courses

- Entry requirements

- Fees, accommodation and living costs

- Scholarships

- Semester dates

- Student visa

- Before you arrive

- Enquire now

How to do a research project for your academic study

- Link copied!

Writing a research report is part of most university degrees, so it is essential you know what one is and how to write one. This guide on how to do a research project for your university degree shows you what to do at each stage, taking you from planning to finishing the project.

What is a research project?

The big question is: what is a research project? A research project for students is an extended essay that presents a question or statement for analysis and evaluation. During a research project, you will present your own ideas and research on a subject alongside analysing existing knowledge.

How to write a research report

The next section covers the research project steps necessary to producing a research paper.

Developing a research question or statement

Research project topics will vary depending on the course you study. The best research project ideas develop from areas you already have an interest in and where you have existing knowledge.

The area of study needs to be specific as it will be much easier to cover fully. If your topic is too broad, you are at risk of not having an in-depth project. You can, however, also make your topic too narrow and there will not be enough research to be done. To make sure you don’t run into either of these problems, it’s a great idea to create sub-topics and questions to ensure you are able to complete suitable research.

A research project example question would be: How will modern technologies change the way of teaching in the future?

Finding and evaluating sources

Secondary research is a large part of your research project as it makes up the literature review section. It is essential to use credible sources as failing to do so may decrease the validity of your research project.

Examples of secondary research include:

- Peer-reviewed journals

- Scholarly articles

- Newspapers

Great places to find your sources are the University library and Google Scholar. Both will give you many opportunities to find the credible sources you need. However, you need to make sure you are evaluating whether they are fit for purpose before including them in your research project as you do not want to include out of date information.

When evaluating sources, you need to ask yourself:

- Is the information provided by an expert?

- How well does the source answer the research question?

- What does the source contribute to its field?

- Is the source valid? e.g. does it contain bias and is the information up-to-date?

It is important to ensure that you have a variety of sources in order to avoid bias. A successful research paper will present more than one point of view and the best way to do this is to not rely too heavily on just one author or publication.

Conducting research

For a research project, you will need to conduct primary research. This is the original research you will gather to further develop your research project. The most common types of primary research are interviews and surveys as these allow for many and varied results.

Examples of primary research include:

- Interviews and surveys

- Focus groups

- Experiments

- Research diaries

If you are looking to study in the UK and have an interest in bettering your research skills, The University of Sheffield is a world top 100 research university which will provide great research opportunities and resources for your project.

Research report format

Now that you understand the basics of how to write a research project, you now need to look at what goes into each section. The research project format is just as important as the research itself. Without a clear structure you will not be able to present your findings concisely.

A research paper is made up of seven sections: introduction, literature review, methodology, findings and results, discussion, conclusion, and references. You need to make sure you are including a list of correctly cited references to avoid accusations of plagiarism.

Introduction

The introduction is where you will present your hypothesis and provide context for why you are doing the project. Here you will include relevant background information, present your research aims and explain why the research is important.

Literature review

The literature review is where you will analyse and evaluate existing research within your subject area. This section is where your secondary research will be presented. A literature review is an integral part of your research project as it brings validity to your research aims.

What to include when writing your literature review:

- A description of the publications

- A summary of the main points

- An evaluation on the contribution to the area of study

- Potential flaws and gaps in the research

Methodology

The research paper methodology outlines the process of your data collection. This is where you will present your primary research. The aim of the methodology section is to answer two questions:

- Why did you select the research methods you used?

- How do these methods contribute towards your research hypothesis?

In this section you will not be writing about your findings, but the ways in which you are going to try and achieve them. You need to state whether your methodology will be qualitative, quantitative, or mixed.

- Qualitative – first hand observations such as interviews, focus groups, case studies and questionnaires. The data collected will generally be non-numerical.

- Quantitative – research that deals in numbers and logic. The data collected will focus on statistics and numerical patterns.

- Mixed – includes both quantitative and qualitative research.

The methodology section should always be written in the past tense, even if you have already started your data collection.

Findings and results

In this section you will present the findings and results of your primary research. Here you will give a concise and factual summary of your findings using tables and graphs where appropriate.

Discussion

The discussion section is where you will talk about your findings in detail. Here you need to relate your results to your hypothesis, explaining what you found out and the significance of the research.

It is a good idea to talk about any areas with disappointing or surprising results and address the limitations within the research project. This will balance your project and steer you away from bias.

Some questions to consider when writing your discussion:

- To what extent was the hypothesis supported?

- Was your research method appropriate?

- Was there unexpected data that affected your results?

- To what extent was your research validated by other sources?

Conclusion

The conclusion is where you will bring your research project to a close. In this section you will not only be restating your research aims and how you achieved them, but also discussing the wider significance of your research project. You will talk about the successes and failures of the project, and how you would approach further study.

It is essential you do not bring any new ideas into your conclusion; this section is used only to summarise what you have already stated in the project.

References

As a research project is your own ideas blended with information and research from existing knowledge, you must include a list of correctly cited references. Creating a list of references will allow the reader to easily evaluate the quality of your secondary research whilst also saving you from potential plagiarism accusations.

The way in which you cite your sources will vary depending on the university standard.

If you are an international student looking to study a degree in the UK , The University of Sheffield International College has a range of pathway programmes to prepare you for university study. Undertaking a Research Project is one of the core modules for the Pre-Masters programme at The University of Sheffield International College.

Frequently Asked Questions

What is the best topic for research .

It’s a good idea to choose a topic you have existing knowledge on, or one that you are interested in. This will make the research process easier; as you have an idea of where and what to look for in your sources, as well as more enjoyable as it’s a topic you want to know more about.

What should a research project include?

There are seven main sections to a research project, these are:

- Introduction – the aims of the project and what you hope to achieve

- Literature review – evaluating and reviewing existing knowledge on the topic

- Methodology – the methods you will use for your primary research

- Findings and results – presenting the data from your primary research

- Discussion – summarising and analysing your research and what you have found out

- Conclusion – how the project went (successes and failures), areas for future study

- List of references – correctly cited sources that have been used throughout the project.

How long is a research project?

The length of a research project will depend on the level study and the nature of the subject. There is no one length for research papers, however the average dissertation style essay can be anywhere from 4,000 to 15,000+ words.

Libraries | Research Guides

Start your research, purpose of this guide, develop a research question, decide on sources, locate your resources.

- Tips for Reading and Notetaking

- Course Reserves This link opens in a new window

- Cite Your Sources

- Individual and Group Study Spaces

- Make an Appointment to Meet with a Librarian This link opens in a new window

This tutorial on research methods will help you gain practical skills and knowledge you can apply for all research needs.

Scroll down to learn about:.

- Developing a Research Question : How do you get background knowledge? Develop a thesis? Start searching?

- Deciding on Sources : What's the difference between academic and popular sources, or primary and secondary sources?

- Locating Sources : How do you locate articles, books and literature reviews both from NUL and other academic institutions?

- Tips for Reading and Note-taking : What are different strategies for reading scholarly articles and books?

Have a question or need help? Contact any NUL Subject Specialist Librarian for personal assistance.

- Build Background on your Topic

- Build a Question

- Videos: Choose and Search Keywords

Somewhere in between your initial idea and settling on a research question, you'll need to do background research on how scholars in a particular subject area have discussed your topic. You may find background research in your textbook or class readings, academic books in the library's collection, or reference sources.

The databases below compile reference sources from a variety of disciplines, and they can be a great way to consider how your topic has been studied from different angles.

- Oxford Bibliographies This link opens in a new window Offers annotated bibliographies of the most important books and articles on specific topics in a growing range of subject areas. Particularly useful for anyone beginning research.

- Oxford Reference Online This link opens in a new window Online version of many Oxford University Press reference works, ranging from specialized dictionaries and companions to major reference works such as the Encyclopedia of Human Rights, the Oxford Encyclopedia of Food and Drink, the Oxford Encyclopedia of Latinos and Latinas in the United States, and the Oxford Encyclopedia of Economic History, among many others.

- CQ Researcher Plus Archive This link opens in a new window The CQ Researcher is a collection of reports covering political and social issues, with regular reports on topics in health, international affairs, education, the environment, technology and the U.S. economy.

Use NU Search to browse for books, reference entries, and periodicals to build background information.

After you have an initial project idea, you can think deeper about the idea by developing a "Topic + Question + Significance" sentence. This formula came from Kate Turabian's Student's Guide to Writing College Papers . Turabian notes that you can use it plan and test your question, but do not incorporate this sentence directly into your paper (p. 13):

TOPIC: I am working on the topic of __________, QUESTION: because I want to find out __________, SIGNIFICANCE: so that I can help others understand __________.

Remember : the shorter your final paper, the narrower your topic needs to be. Having trouble?

- Which specific subset of the topic you can focus on? Specific people, places, or times?

- Is there a cause and effect relationship you can explore?

- Is there something about this topic that is not addressed in scholarship?

Turabian, Kate L. Student's Guide to Writing College Papers . 4th edition. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. 2010.

How do you move from a research question to searching in a database? You first have to pick out keywords from your research question.

- Evaluating Sources

- Academic vs. Popular Publications

- Primary vs. Secondary Sources

- Video: Types of Scholarly Articles

When evaluating a source of information, consider both the content of the source itself and the context in which the source was created.

CONTENT

- What does it say? What is its main point or argument? Relevance to your topic? What new information, facts, or opinions does it include?

- Where did you find it? Where was it published?

- When was it written? Within the past few days, weeks, or years? Is it historical? Has its information changed over time?

- Who created this information? What are their credentials?

- Why does this source exist? Is its purpose to inform, persuade, or entertain?

- How does it incorporate data or evidence? What kinds of evidence?

CONTEXT

- What is the audience for this source? General readers, people who work in a specific field, academics? Does it assume previous knowledge?

- Where can you find other information about this topic?

- When was this information last updated? Has it been revised, redacted, or challenged?

- Who is missing from the conversation? Does it include opposing viewpoints, marginalized voices, or global perspectives?

- Why do you need this information? Is it for an academic assignment, work project, personal decision-making, or to share with others?*

- How did the information find you? Was it through a relevance-ranked search, social media algorithm, advertising cookie, or press release?

*Sources that may be appropriate for sharing with others, deepening personal understanding, or decision-making may not be appropriate for an academic assignment or work presentation. When in doubt, check with your librarian or professor for more guidance!

Adapted from Beyond the Source created by the DePaul University Libraries .

Not all "articles" are the same! They have different purposes and different "architecture".

- Original article – information based on original research

- Case reports – usually of a single case

- Technical notes - describe a specific technique or procedure

- Pictorial essay – teaching article with images

- Review – detailed analysis of recent research on a specific topic

- Commentary – short article with author’s personal opinions

- Editorial – often short review or critique of original articles

- Letter to the Editor – short & on subject of interest to readers

Peh, WCG and NG, KH. (2008) "Basic Structure and Types of Scientific Papers." Singapore Medical Journal , 48 (7) : 522-525. http://smj.sma.org.sg/4907/4907emw1.pdf accessed 4/24/19.

- What are the differences between types of articles? "Scholarly articles," "trade journals," "popular magazines," and "newspapers" are all referred to as "articles" - pretty confusing, right?! Check out this table which distinguishes between the different kinds of "articles" that could be useful sources.

Primary sources provide the raw data you use to support your arguments. Some common types of primary resources include manuscripts, diaries, court cases, maps, data sets, experiment results, news stories, polls, or original research. One other way to think about primary sources is the author was there .

Secondary sources analyze primary sources, using primary source materials to answer research questions. Secondary sources may analyze, criticize, interpret or summarize data from primary sources. The most common secondary resources are books, journal articles, or reviews of the literature.

Depending on the subject in which you are doing your research, what counts as a primary or secondary source can vary! Here are some examples of types of sources that relate to dragons in different disciplines:

| If your class is in... | Primary Source Example | Secondary Source Example |

| English | ||

| Anthropology | (photo) | |

| Biology | ... |

There are many types of primary resources, so it is important to define your parameters by:

- Discipline (e.g. art, history, physics, political science)

- Format (e.g. book, manuscript, map, photograph)

- Type of information you need (e.g. numerical data, images, polls, government reports, letters)

Look at the Primary and Secondary Sources guide for more clarification on what primary and secondary sources are in different disciplines!

- Find Articles

- Videos: Books at NU and Other Libraries

- Find Literature Reviews

Northwestern has access to millions of articles not available through Google!

From the library website , enter your keywords into the NUSearch search box. All results with those keywords in the title or description will appear in the search results. Limit your results to "Peer-reviewed Journals" for scholarly articles.

For a more specific search, go to one of the Libraries' many scholarly databases. If you know the name of your database, find it with Databases A-Z . Find subject-specific lists of databases in our Research Guides.

Searching a scholarly database is different from using a Google search. When searching:

- Use an advanced search, which allows you to search for multiple keywords. "AND" allows you to enter more than one term in multiple search boxes to focus your search (e.g. apples AND oranges) for articles about both. "OR" broadens your results (e.g. apples OR oranges) for articles about either.

- The results may link to a full-text version of the article, but if one is not available, the library can likely get it for you! Clicking the "Find it @ NU" button on the database's left-hand navigation will display other Northwestern databases that may have access to it. If we don't have access to the article, request it through Interlibrary Loan.

Locating Books

To locate a book, use the NUsearch. The catalog will tell you the location and call number for retrieval. You can also request for books to be pulled and picked up at the Circulation desk of your choosing.

Borrowing Materials from other Institutions

Need to borrow a book Northwestern does not own or have an article PDF scanned and sent to you? Log into (or create) your interlibrary loan account. You may also check the status of your interlibrary loan requests here. Contact the Interlibrary Loan Department for more assistance.

- Interlibrary Loan Department

- Annual Reviews The Annual Reviews provide substantially researched articles written by recognized scholars in a wide variety of disciplines that summarize the major research literature in the field. These are often a good place to start your research and to keep informed about recent developments.

- Oxford Handbooks Online Scholarly reviews of research in 15 subject fields including: Archaeology, Business/Management, Classical Studies, Criminology/Criminal Justice, Economics/Finance, History, Law, Linguistics, Literature, Music, Neuroscience, Philosophy, Physical Sciences, Political Science, Psychology, Religion, Sociology.

Search for literature review articles in subject databases:

- Type the phrase "Literature Review" (with quotation marks) as a search term OR

- Look to see if there is an option to limit your search results by Document Type (this may appear underneath the search box or among the filters on the left side of the search results display).

Be careful The document type "Review" is often used and may identify articles that are book reviews, software reviews or reviews of films, performances, art exhibits, etc.

Need Help? Ask Your Librarian

Created by...

Created and maintained by Instruction & Curriculum Support , with content also developed by Chris Davidson, Jason Kruse, Gina Petersen, and Amy Odwarka (intern, fall 2019).

- Next: Tips for Reading and Notetaking >>

- Last Updated: May 2, 2024 10:39 AM

- URL: https://libguides.northwestern.edu/start-research

How to Start a Research Project: Home

- Video Tutorials

Getting Started

This guide will help you get started with the research process and organize your results in order to manage the many steps involved in doing research.

You may also be interested in the following guides:

- The Research Process: A Suggested Timeline

- Current Events, Opposing Viewpoints, and Controversial Issues

- How To Do A Word Study Without Knowing Hebrew Or Greek

- How to Write an Annotated Bibliography

- How to Write an Exegesis Paper with Library Resources

What's Here?

Step 1: understand the assignment.

Step 2: Choose a Topic

Step 3: Develop a Research Question

Step 4: identify keywords, step 5: develop a search string, step 6: choose the right database, step 7: mark, save, and email your results, step 8: write your paper, step 9: cite your sources, need more help.

Research can be a complex, lengthy, and sometimes intimidating process, but the APU Libraries can help. Librarians are always available to give you customized research suggestions, and you can find books and articles (print and online) via the APU Libraries website .

Subject-Specific Research Assistance

Did you know that there's a librarian who specializes in helping students from your major? Contact your subject librarian for customized help.

Identifying the amount and types of sources your assignment requires will help you choose the right online research tools.

Before you begin developing a strategy for searching the library catalog and databases, you should clarify several things about the assignment:

- What type of assignment is it? (Research paper, essay, opinion paper, review, or other?)

- How long does your paper need to be?

- How many sources do you need for your bibliography?

- What types of information do you need? (Statistics, Web pages, books, articles, images, audio/video clips, or other?)

- Do you need current or historical sources? Or both?

If you are unclear on any of the requirements, ASK YOUR PROFESSOR ASAP ! Doing this early in the semester will save you stress later on and will show your professor that you are proactive.

Step 2: Choose a Topic

Sometimes your topic is assigned by your professor. However, most of the time your professor will give you the freedom to choose your own research topic. Choosing a topic that is specific enough to be manageable without being too narrow can be difficult, but these steps can help.

First, think about what topics might be of interest to you. You can get ideas by skimming your textbook, reading news magazines like Time , or keeping an eye on the news.

Once you've identified a broad topic, looking at a few scholarly reference books (such as dictionaries and encyclopedias) can help you figure out which authors and sources are the most important to know about. Scholarly encyclopedias can also help you discover narrower aspects of your broad topic so that your topic is more manageable.

Often a scholarly reference book will give you a short, authoritative overview of your topic and suggest additional sources for you to read. In essence, reading a reference article can save you time and give you a head-start on your project!

There are two easy ways to find reference material. First, try doing a keyword search of the APU Library Catalog for your topic, limiting your search to the Reference collection (use the drop-down "View Entire Collection" menu and choose "Reference"). Second, try searching for your topic in an online reference database , such as Credo Reference , Gale Virtual Reference Library , Oxford Reference Online , or SAGE eReference .

After you've identified and narrowed a research topic, you should re-state it in the form of a research question. Phrasing your topic in the form of a question helps to direct your research process.

Asking whether a fact or statistic directly answers your research question can help you find the most relevant information for your topic. A good research question also leads to a direct answer in the form of a thesis.

A sample research question might be: What are some strategies for improving employee retention among female law enforcement officers?

This question might lead to the following thesis in the final paper: "Recommended strategies for improving employee retention among female law enforcement officers include: flexible benefits and scheduling, diversity training, and..."

A good research question also helps you pull out the different concepts your research will cover. Concepts are discrete ideas that can be researched independently from each other, although most of the time you are looking for research on how multiple concepts interact with each other. Our example, "What are some strategies for improving employee retention among female law enforcement officers?" has 3 distinct concepts:

- Employee retention

- Law enforcement officers

These concepts will become the search keywords you will use in the Library Catalog and online article databases. Keywords are words that appear in the title, table of contents, and other parts of the book or article record in the catalog or database. Keyword searching is different from subject searching, since a keyword search will only return results that exactly match the terms you enter . Searching by subject headings will allow you to pull up books and articles on that topic, regardless of whether or not a particular keyword appears in the record. For more information on subject searching, see our LibGuide on Finding Library Resources by Subject .

Keep in mind that not every author will use the same keywords to describe a topic: one author might write about "police officers," and another might use the phrase "law enforcement officers."

For this reason, you will want to identify some synonyms and related terms for each of your keywords before you start searching. For example:

- Synonyms/related terms: recruitment, promotion, advancement, loyalty

- Synonyms/related terms: women, mothers

- Synonyms/related terms: police, sheriff, cops

Once you've identified your search terms and synonyms, the final pre-search step is to combine those terms into search strings.

To give you the most precise results, online search tools like the library catalog and databases require a specific format for search statements, including the use of words called Boolean operators . Boolean operators are the words AND, OR, and NOT. Placing these words between your search terms will help you find books and articles that are targeted to your research topic.

The Boolean operator AND gives you more targeted results by requiring that two or more terms all appear within the title, abstract, or table of contents of a book or article. Let's imagine we are looking for information on workplace discrimination.

A keyword search in the library catalog for "discrimination" returns 423 titles.

A keyword search for "discrimination AND workplace" returns only 12 titles, but those 12 are much more relevant to our topic.

The Boolean operator OR is the opposite of AND. OR generally gives you more search results by requiring either one term or another to appear in a book or article. OR works best when you are looking for synonyms or related terms.

For example, a keyword search in the library catalog for "recruitment" returns 62 titles.

A keyword search for "recruitment OR retention" returns 141 titles.

A keyword search for "recruitment AND retention" returns 17 titles.

There are 2 types of research sources that can be found through the APU Libraries web site: books and articles.

To find books, use the APU Library Catalog :

To find articles, use a database. This short video from RMIT (an Australian university) can help you understand what library databases contain and how they work: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=KKIbnNLCh8g&feature=player_embedded

APU subscribes to more than 120 subscription databases , so it can be tricky to find the right one! The easiest way to choose the right database for your topic is to use the subject menu on the "All Databases" page--it will help you find a database recommended for your subject.

Still not sure? A good multidisciplinary database to begin with is Academic Search Premier :

(Search results will open in a new window.)

Once you've started finding books and articles on your topic, be sure to save the information. This will save you time as you organize your notes and start preparing your bibliography.

In the APU Library Catalog , you can download information about the books you find by adding them to your book bag:

Then, click the "View Bag" button and follow the directions to print, save, or email your records:

You can also automatically generate an APA, MLA, or Chicago-style citation for the books you find by clicking on the "WorldCat Citations" link from the catalog record:

In online databases , look for buttons or checkbozes to mark your articles or save them in a folder. Then look for print/email/save options; usually you can also choose to have a pre-formatted citation (in APA, MLA, or Chicago style) included in the email or saved file.

If the database you're using does not have a full-text copy of the article you need, click on the "Full Text Finder" button. The Full Text Finder will tell you if there is a copy of the article in another database; if so, it will link you to the full text.

If the Full Text Finder indicates that full text is not available, it will provide you with a link to the ArticleReach service. Click the link to request a free, scanned copy of the article from another library. For more information about ArticleReach, please see our ArticleReach guide .

By this point, you should have a pretty good idea of what your main points are. If you want some help with the writing process , you should schedule an appointment with the APU Writing Center . The writing tutors can give you tips, feedback, and suggestions that can help you write a great paper!

It is important that you cite your information sources correctly in your paper, for several reasons:

- You need to give credit to the original author of your information.

- If you don't cite your sources, you may be accused of plagiarism .

- Providing citations shows your professor that you have devoted time and effort to researching your topic.

- Citations help future readers of your work locate the sources you've used, so that they can build upon the research you've started.

If you need help citing sources, there are several how-to guides available in the LibGuides system.

- Next: Video Tutorials >>

- Last Updated: Sep 26, 2023 9:42 AM

- URL: https://apu.libguides.com/startresearch

- Privacy Policy

Home » How To Write A Research Proposal – Step-by-Step [Template]

How To Write A Research Proposal – Step-by-Step [Template]

Table of Contents

How To Write a Research Proposal

Writing a Research proposal involves several steps to ensure a well-structured and comprehensive document. Here is an explanation of each step:

1. Title and Abstract

- Choose a concise and descriptive title that reflects the essence of your research.

- Write an abstract summarizing your research question, objectives, methodology, and expected outcomes. It should provide a brief overview of your proposal.

2. Introduction:

- Provide an introduction to your research topic, highlighting its significance and relevance.

- Clearly state the research problem or question you aim to address.

- Discuss the background and context of the study, including previous research in the field.

3. Research Objectives

- Outline the specific objectives or aims of your research. These objectives should be clear, achievable, and aligned with the research problem.

4. Literature Review:

- Conduct a comprehensive review of relevant literature and studies related to your research topic.

- Summarize key findings, identify gaps, and highlight how your research will contribute to the existing knowledge.

5. Methodology:

- Describe the research design and methodology you plan to employ to address your research objectives.

- Explain the data collection methods, instruments, and analysis techniques you will use.

- Justify why the chosen methods are appropriate and suitable for your research.

6. Timeline:

- Create a timeline or schedule that outlines the major milestones and activities of your research project.

- Break down the research process into smaller tasks and estimate the time required for each task.

7. Resources:

- Identify the resources needed for your research, such as access to specific databases, equipment, or funding.

- Explain how you will acquire or utilize these resources to carry out your research effectively.

8. Ethical Considerations:

- Discuss any ethical issues that may arise during your research and explain how you plan to address them.

- If your research involves human subjects, explain how you will ensure their informed consent and privacy.

9. Expected Outcomes and Significance:

- Clearly state the expected outcomes or results of your research.

- Highlight the potential impact and significance of your research in advancing knowledge or addressing practical issues.

10. References:

- Provide a list of all the references cited in your proposal, following a consistent citation style (e.g., APA, MLA).

11. Appendices:

- Include any additional supporting materials, such as survey questionnaires, interview guides, or data analysis plans.

Research Proposal Format

The format of a research proposal may vary depending on the specific requirements of the institution or funding agency. However, the following is a commonly used format for a research proposal:

1. Title Page:

- Include the title of your research proposal, your name, your affiliation or institution, and the date.

2. Abstract:

- Provide a brief summary of your research proposal, highlighting the research problem, objectives, methodology, and expected outcomes.

3. Introduction:

- Introduce the research topic and provide background information.

- State the research problem or question you aim to address.

- Explain the significance and relevance of the research.

- Review relevant literature and studies related to your research topic.

- Summarize key findings and identify gaps in the existing knowledge.

- Explain how your research will contribute to filling those gaps.

5. Research Objectives:

- Clearly state the specific objectives or aims of your research.

- Ensure that the objectives are clear, focused, and aligned with the research problem.

6. Methodology:

- Describe the research design and methodology you plan to use.

- Explain the data collection methods, instruments, and analysis techniques.

- Justify why the chosen methods are appropriate for your research.

7. Timeline:

8. Resources:

- Explain how you will acquire or utilize these resources effectively.

9. Ethical Considerations:

- If applicable, explain how you will ensure informed consent and protect the privacy of research participants.

10. Expected Outcomes and Significance:

11. References:

12. Appendices:

Research Proposal Template

Here’s a template for a research proposal:

1. Introduction:

2. Literature Review:

3. Research Objectives:

4. Methodology:

5. Timeline:

6. Resources:

7. Ethical Considerations:

8. Expected Outcomes and Significance:

9. References:

10. Appendices:

Research Proposal Sample

Title: The Impact of Online Education on Student Learning Outcomes: A Comparative Study

1. Introduction

Online education has gained significant prominence in recent years, especially due to the COVID-19 pandemic. This research proposal aims to investigate the impact of online education on student learning outcomes by comparing them with traditional face-to-face instruction. The study will explore various aspects of online education, such as instructional methods, student engagement, and academic performance, to provide insights into the effectiveness of online learning.

2. Objectives

The main objectives of this research are as follows:

- To compare student learning outcomes between online and traditional face-to-face education.

- To examine the factors influencing student engagement in online learning environments.

- To assess the effectiveness of different instructional methods employed in online education.

- To identify challenges and opportunities associated with online education and suggest recommendations for improvement.

3. Methodology

3.1 Study Design

This research will utilize a mixed-methods approach to gather both quantitative and qualitative data. The study will include the following components:

3.2 Participants

The research will involve undergraduate students from two universities, one offering online education and the other providing face-to-face instruction. A total of 500 students (250 from each university) will be selected randomly to participate in the study.

3.3 Data Collection

The research will employ the following data collection methods:

- Quantitative: Pre- and post-assessments will be conducted to measure students’ learning outcomes. Data on student demographics and academic performance will also be collected from university records.

- Qualitative: Focus group discussions and individual interviews will be conducted with students to gather their perceptions and experiences regarding online education.

3.4 Data Analysis

Quantitative data will be analyzed using statistical software, employing descriptive statistics, t-tests, and regression analysis. Qualitative data will be transcribed, coded, and analyzed thematically to identify recurring patterns and themes.

4. Ethical Considerations

The study will adhere to ethical guidelines, ensuring the privacy and confidentiality of participants. Informed consent will be obtained, and participants will have the right to withdraw from the study at any time.

5. Significance and Expected Outcomes

This research will contribute to the existing literature by providing empirical evidence on the impact of online education on student learning outcomes. The findings will help educational institutions and policymakers make informed decisions about incorporating online learning methods and improving the quality of online education. Moreover, the study will identify potential challenges and opportunities related to online education and offer recommendations for enhancing student engagement and overall learning outcomes.

6. Timeline

The proposed research will be conducted over a period of 12 months, including data collection, analysis, and report writing.

The estimated budget for this research includes expenses related to data collection, software licenses, participant compensation, and research assistance. A detailed budget breakdown will be provided in the final research plan.

8. Conclusion

This research proposal aims to investigate the impact of online education on student learning outcomes through a comparative study with traditional face-to-face instruction. By exploring various dimensions of online education, this research will provide valuable insights into the effectiveness and challenges associated with online learning. The findings will contribute to the ongoing discourse on educational practices and help shape future strategies for maximizing student learning outcomes in online education settings.

About the author

Muhammad Hassan

Researcher, Academic Writer, Web developer

You may also like

Research Proposal – Types, Template and Example

Business Proposal – Templates, Examples and Guide

Proposal – Types, Examples, and Writing Guide

How To Write A Proposal – Step By Step Guide...

How To Write A Grant Proposal – Step-by-Step...

How to choose an Appropriate Method for Research?

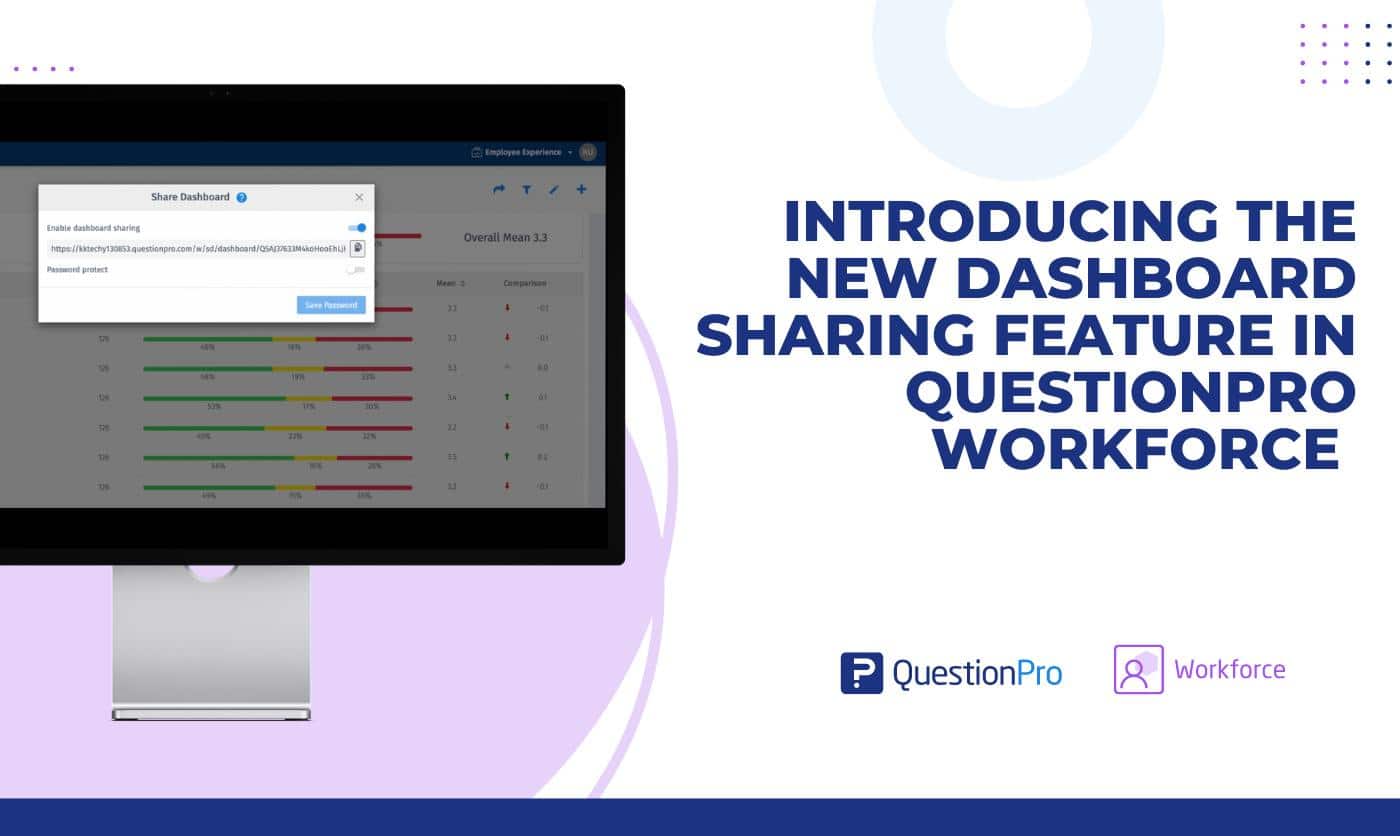

How to Set Up a Research Project (in 6 Steps)

Written by Casey Scott-Songin

Research projects, 0 comment(s).

It can be really exciting to embark on a research project, but knowing where to start can feel overwhelming! Setting up a research project properly means that you will save yourself a lot of stress, worrying about whether you’ll collect useful information, and will save you time analysing results!

Before you even begin to think about what research method you should use or where to recruit participants , you need to think about the purpose, objectives, and key research questions for your project. Below are the six steps to starting a research project that you can be confident in!

1. Define your purpose

The first thing you need to do is have a clear understanding of the purpose of your project. If you had to summarise why you wanted to do this project in two to three sentences, what would they be?

These should include:

- what problem you are trying to solve

- the context for that problem

- the purpose of the project

The problem you are trying to solve

Think about how to summarise your main problem in one sentence. Is it that your product is not selling? Are you not sure why some ads are more successful than others? Is it that you are struggling to grow you client list? Or maybe There is a high bounce rate on a particular page on your website. Whatever it is, clearly identify it in one sentence (okay, two sentences maximum).

The context for that problem