Greater Good Science Center • Magazine • In Action • In Education

Family Conflict Is Normal; It’s the Repair That Matters

Three months into the pandemic, I had the urge to see my 28-year-old daughter and her husband, 2,000 miles away. She had weathered an acute health crisis, followed by community protests that propelled them both onto the streets to serve food and clean up neighborhoods. They were coping, but the accumulation of challenges made the mom in me want to connect with and support them. So, together with my husband, my other daughter, and her husband, our family of six adults and two dogs formed a new pod inside my daughter’s home in the steamy heat of the Minneapolis summer.

As I packed, a wisp of doubt crept in. We six hadn’t lived together under the same roof, ever . Would I blow it? Would I “flap my lips,” as a friend calls it, and accidentally say something hurtful? Some time back, in a careless moment of exhaustion, I had insulted my brand-new son-in-law with a thoughtless remark. He was rightfully hurt, and it took a long letter and a phone call to get us back on track.

My own siblings and I were raised inside the intractable rupture that was my parents’ marriage. Their lifelong conflict sowed discord and division in everyone around them. I worked hard to create a different, positive family climate with my husband and our children. My old ghosts were haunting me, though, and I didn’t want to ruin a good thing.

Yet research shows that it’s not realistic, or possible, or even healthy to expect that our relationships will be harmonious all the time. Everything we know from developmental science and research on families suggests that rifts will happen—and what matters more is how you respond to them. With many families spending more time together than ever now, there are ample opportunities for tension and hurt feelings. These moments also offer ample invitations to reconnect.

Disconnections are a fact of life

Researcher Ed Tronick, together with colleague Andrew Gianino, calculated how often infants and caregivers are attuned to each other. (Attunement is a back-and-forth rhythm of interaction where partners share positive emotions.) They found that it’s surprisingly little. Even in healthy, securely attached relationships, caregivers and babies are in sync only 30% of the time. The other 70%, they’re mismatched, out of synch, or making repairs and coming back together. Cheeringly, even babies work toward repairs with their gazes, smiles, gestures, protests, and calls.

These mismatches and repairs are critical, Tronick explains. They’re important for growing children’s self-regulation, coping, and resilience. It is through these mismatches—in small, manageable doses—that babies, and later children, learn that the world does not track them perfectly. These small exposures to the micro-stress of unpleasant feelings, followed by the pleasant feelings that accompany repair, or coming back together, are what give them manageable practice in keeping their boat afloat when the waters are choppy. Put another way, if a caregiver met all of their child’s needs perfectly, it would actually get in the way of the child’s development. “Repairing ruptures is the most essential thing in parenting,” says UCLA neuropsychiatrist Dan Siegel , director of the Mindsight Institute and author of several books on interpersonal neurobiology.

Life is a series of mismatches, miscommunications, and misattunements that are quickly repaired, says Tronick , and then again become miscoordinated and stressful, and again are repaired. This occurs thousands of times in a day, and millions of times over a year.

Greater Good in Spanish

Read this article in Spanish on La Red Hispana, the public-facing media outlet and distribution house of HCN , focused on educating, inspiring, and informing 40 million U.S. Hispanics.

Other research shows that children have more conflicts and repairs with friends than non-friends. Sibling conflict is legendary; and adults’ conflicts escalate when they become parents. If interpersonal conflict is unavoidable—and even necessary—then the only way we can maintain important relationships is to get better at re-synchronizing them, and especially at tending to repairs when they rupture.

“Relationships shrink to the size of the field of repair,” says Rick Hanson , psychologist and author of several books on the neuroscience of well-being. “But a bid for a repair is one of the sweetest and most vulnerable and important kinds of communication that humans offer to each other,” he adds. “It says you value the relationship.”

Strengthening the family fabric

In a small Canadian study , researchers examined how parents of four- to seven-year-old children strengthened, harmed, or repaired their relationships with their children. Parents said their relationships with their children were strengthened by “horizontal” or egalitarian exchanges like playing together, negotiating, taking turns, compromising, having fun, or sharing psychological intimacy—in other words, respecting and enjoying one another. Their relationships were harmed by an over-reliance on power and authority, and especially by stonewalling tactics like the “silent treatment.” When missteps happened, parents repaired and restored intimacy by expressing warmth and affection, talking about what happened, and apologizing.

This model of strengthening, harming, and repairing can help you think about your own interactions. When a family relationship is already positive, there is a foundation of trust and a belief in the other’s good intentions, which helps everyone restore more easily from minor ruptures. For this reason, it helps to proactively tend the fabric of family relationships. That can begin with simply building up an investment of positive interactions:

- Spend “special time” with each child individually to create more space to deepen your one-to-one relationship. Let them control the agenda and decide how long you spend together.

- Appreciate out loud, share gratitude reflections, and notice the good in your children intermittently throughout the day or week.

You also want to watch out for ways you might harm the relationship. If you’re ever unsure about a child’s motives, check their intentions behind their behaviors and don’t assume they were ill-intentioned. Language like, “I noticed that…” or “Tell me what happened…” or “And then what happened?” can help you begin to understand an experience from the child’s point of view.

A Loving Space for Kids’ Emotions

Show love to your children by helping them process emotions

When speaking to a child, consider how they might receive what you’re saying. Remember that words and silence have weight; children are “ emotional Geiger counters ” and read your feelings much more than they process your words. If you are working through feelings or traumas that have nothing to do with them, take care to be responsible for your own feelings and take a moment to calm yourself before speaking.

In this context of connection and understanding, you can then create a family culture where rifts are expected and repairs are welcomed:

- Watch for tiny bids for repairs . Sometimes we have so much on our minds that we miss the look, gesture, or expression in a child that shows that what they really want is to reconnect.

- Normalize requests like “I need a repair” or “Can we have a redo?” We need to be able to let others know when the relationship has been harmed.

- Likewise, if you think you might have stepped on someone’s toes, circle back to check. Catching a misstep early can help.

When you’re annoyed by a family member’s behavior, try to frame your request for change in positive language; that is, say what you want them to do rather than what you don’t. Language like, “I have a request…” or “Would you be willing to…?” keeps the exchange more neutral and helps the recipient stay engaged rather than getting defensive.

You can also model healthy repairs with people around you, so they are normalized and children see their usefulness in real time. Children benefit when they watch adults resolve conflict constructively.

Four steps to an authentic repair

There are infinite varieties of repairs, and they can vary in a number of ways, depending on your child’s age and temperament, and how serious the rift was.

Infants need physical contact and the restoration of love and security. Older children need affection and more words. Teenagers may need more complex conversations. Individual children vary in their styles—some need more words than others, and what is hurtful to one child may not faze another child. Also, your style might not match the child’s, requiring you to stretch further.

Some glitches are little and may just need a check-in, but deeper wounds need more attention. Keep the apology in proportion to the hurt. What’s important is not your judgment of how hurt someone should be, but the actual felt experience of the child’s hurt. A one-time apology may suffice, but some repairs need to be acknowledged frequently over time to really stitch that fabric back together. It’s often helpful to check in later to see if the amends are working.

While each repair is unique, authentic repairs typically involve the same steps.

1. Acknowledge the offense. First, try to understand the hurt you caused. It doesn’t matter if it was unintentional or what your reasons were. This is the time to turn off your own defense system and focus on understanding and naming the other person’s pain or anger.

Sometimes you need to check your understanding. Begin slowly: “Did I hurt you? Help me understand how.” This can be humbling and requires that we listen with an open heart as we take in the other person’s perspective.

Try not to undermine the apology by adding on any caveats, like blaming the child for being sensitive or ill-behaved or deserving of what happened. Any attempt to gloss over, minimize, or dilute the wound is not an authentic repair. Children have a keen sense for authenticity. Faking it or overwhelming them will not work.

A spiritual teacher reminded me of an old saying, “It is acknowledging the wound that gets the thorn out.” It’s what reconnects our humanity.

Making an Effective Apology

A good apology involves more than saying "sorry"

2. Express remorse. Here, a sincere “I’m sorry” is sufficient.

Don’t add anything to it. One of the mistakes adults often make, according to therapist and author Harriet Lerner , is to tack on a discipline component: “Don’t let it happen again,” or “Next time, you’re really going to get it.” This, says Lerner, is what prevents children from learning to use apologies themselves. Apologizing can be tricky for adults. It might feel beneath us, or we may fear that we’re giving away our power. We shouldn’t have to apologize to a child, because as adults we are always right, right? Of course not. But it’s easy to get stuck in a vertical power relationship to our child that makes backtracking hard.

On the other hand, some adults—especially women, says Rick Hanson —can go overboard and be too effusive, too obsequious, or even too quick in their efforts to apologize. This can make the apology more about yourself than the person who was hurt. Or it could be a symptom of a need for one’s own boundary work.

There is no perfect formula for an apology except that it be delivered in a way that acknowledges the wound and makes amends. And there can be different paths to that. Our family sometimes uses a jokey, “You were right, I was wrong, you were right, I was wrong, you were right, I was wrong,” to playfully acknowledge light transgressions. Some apologies are nonverbal: My father atoned for missing all of my childhood birthdays when he traveled 2,000 miles to surprise me at my doorstep for an adult birthday. Words are not his strong suit, but his planning, effort, and showing up was the repair. Apologies can take on all kinds of tones and qualities.

3. Consider offering a brief explanation. If you sense that the other person is open to listening, you can provide a brief explanation of your point of view, but use caution, as this can be a slippery slope. Feel into how much is enough. The focus of the apology is on the wounded person’s experience. If an explanation helps, fine, but it shouldn’t derail the intent. This is not the time to add in your own grievances—that’s a conversation for a different time.

4. Express your sincere intention to fix the situation and to prevent it from happening again. With a child, especially, try to be concrete and actionable about how the same mistake can be prevented in the future. “I’m going to try really hard to…” and “Let’s check back in to see how it’s feeling…” can be a start.

Remember to forgive yourself, too. This is a tender process, we are all works in progress, and adults are still developing. I know I am.

Prior to our visit, my daughter and I had a phone conversation. We shared our excitement about the rare chance to spend so much time together. Then we gingerly expressed our concerns.

“I’m afraid we’ll get on each other’s nerves,” I said.

“I’m afraid I’ll be cooking and cleaning the whole time,” she replied.

So we strategized about preventing these foibles. She made a spreadsheet of chores where everyone signed up for a turn cooking and cleaning, and we discussed the space needs that people would have for working and making phone calls.

Then I drew a breath and took a page from the science. “I think we have to expect that conflicts are going to happen,” I said. “It’s how we work through them that will matter. The love is in the repair.”

This article is excerpted from a longer article on Diana Divecha’s blog, developmentalscience.com.

About the Author

Diana Divecha

Diana Divecha, Ph.D. , is a developmental psychologist, an assistant clinical professor at the Yale Child Study Center and Yale Center for Emotional Intelligence, and on the advisory board of the Greater Good Science Center. Her blog is developmentalscience.com .

You May Also Enjoy

What Makes an Effective Apology

How to Teach Siblings to Resolve Their Own Arguments

What Happens to Kids When Parents Fight

The Three Parts of an Effective Apology

Should You Ask Your Children to Apologize?

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- HHS Author Manuscripts

The interactive effect of family conflict history and physiological reactivity on different forms of aggression in young women

Melissa j. hagan.

a San Francisco State University, United States

b University of California, San Francisco, United States

Sara F. Waters

c Washington State University, Vancouver, United States

Sarah Holley

Lucy moctezuma, miya gentry.

Evidence indicates that patterns of biological reactivity underlie different forms of aggression, but greater precision is needed in research targeting biopsychosocial processes that underlie such differences. This study investigated how sympathetic and parasympathetic nervous system (SNS and PNS) responses to social stress were associated with multiple forms of aggression in an ethnically-diverse sample of young adult females; it further examined whether early life exposure to family conflict moderated these relationships. In the context of high levels of family conflict history, greater SNS activation during a social conflict task was associated with more direct proactive aggression and increasing RSA was associated with more direct reactive aggression. Greater SNS activation during the task was associated with more direct reactive aggression regardless of family conflict history. Our findings affirm the need to capture the contributions of multiple physiological systems simultaneously and the importance of considering family history in the study of aggression.

1. Introduction

Young adults’ behavioral patterns forecast the quality of subsequent interactions with long-term partners and offspring, making this developmental period a critical time for interrupting cycles of aggression. A significant body of literature suggests that patterns of biological reactivity may underlie different forms of aggression, but greater precision is needed in research targeting the specific dynamic biopsychosocial processes that underlie such differences. Notably, studies on the psychophysiology of aggression have historically focused on males and have largely ignored the role of young adults’ early family environment, despite the strong influence that childhood experiences exert on long-term behavior problems. To address these gaps in the literature, the present study examined the associations between autonomic reactivity in response to social conflict and different forms of aggression in an ethnically-diverse sample of young adult females. It additionally sought to determine whether these associations are moderated by exposure to family conflict during childhood. In addition to shedding light on biological processes implicated in female aggression, this work has the potential to lead to more specificity in violence prevention research relevant to a developmental period largely overlooked in prevention science.

1.1. Psychophysiological stress reactivity and aggression

Multiple theories recognize that physiological arousal is a key component of aggression ( Anderson & Bushman, 2002 ; Goozen, Fairchild, & Harold, 2007 ) and that the interaction of psychosocial and biological mechanisms underlying aggressive and violent behavior must be more fully understood ( Murray-Close, 2013 ). Most studies on the physiology of aggression have focused on the autonomic nervous system (ANS), which is composed of the sympathetic (SNS) and parasympathetic (PNS) nervous systems ( Murray-Close & Rellini, 2012 ; Patrick & Verona, 2007 ). The SNS is responsible for supporting bodily functions during episodes of stress while the PNS is responsible for supporting bodily functions of rest; as such, each are regarded has having opposing effects on the body. Engagement of the SNS during stress underlies the “fight or flight” somatic response, resulting in glucose increases, elevation in heart rate and increased blood pressure. To facilitate this reactivity, withdrawal of the PNS occurs. Stress-induced change in PNS activity is determined by measuring the influence of the tenth cranial nerve, the vagus, on the heart. PNS activation (whereby the PNS is engaged rather than withdrawn during stress) is often referred to as vagal augmentation, or increased influence of the vagus, and vagal withdrawal describes decreased influence ( Mendes, 2009 ).

The body of work on ANS reactivity and aggression has produced inconsistent and often contradictory findings. For example, a number of studies have found that aggression in adulthood is associated with greater ANS reactivity to stress as indicated by elevated sympathetic reactivity ( Beauchaine, Gatzke-Kopp, & Mead, 2007 ; Lorber, 2004 ; Murray-Close & Crick, 2007 ). Conversely, other investigations have reported associations between aggression and lower ANS reactivity, as indicated by blunted sympathetic reactivity ( Ortiz & Raine, 2004 ; Posthumus, Böcker, Raaijmakers, Van Engeland, & Matthys, 2009 ) or blunted withdrawal of the parasympathetic system (i.e., vagal augmentation; Calkins, Graziano, & Keane, 2007 ; Katz, 2007 ; Obradović, Bush, Stamperdahl, Adler, & Boyce, 2010 ).

This inconsistency in the field is likely due to a number of issues. First, research in this area has tended to rely on non-specific measures of isolated parts of the human stress response system. As an example, an impressive body of research documents negative associations between resting heart rate or heart rate reactivity and aggression or disorders associated with aggression (i.e. conduct disorder, oppositional defiant disorder, antisocial personality disorder) ( Lorber, 2004 ; Ortiz & Raine, 2004 ). Heart rate reflects both SNS and PNS influences on the heart; the relative contributions of the two systems cannot be disentangled from this measure. A more complete understanding of how the ANS is related to aggression may be obtained by effectively measuring the two branches of the ANS independently and then examining their associations with aggression separately and in light of the other.

Second, much of the research on the psychophysiology of aggression has lacked specificity in aggression measurement. Several critical distinctions have been suggested regarding different forms of aggression. Direct aggression involves both overt physical attacks and verbal assaults of the intended victim, although many studies focus on physical aggression , specifically. Conversely, indirect aggression , which has also been referred to as relational aggression , involves harm delivered circuitously and/or through relational means such as social exclusion or spreading rumors ( Crick, Casas, & Mosher, 1997 ). While there may be differences in the neurobiological underpinnings of direct and indirect aggression, research exploring these distinctions is fairly limited ( Murray-Close & Crick, 2007 ; Murray-Close, Han, Cicchetti, Crick, & Rogosch, 2008 ; Sijtsema, Shoulberg, & Murray-Close, 2011 ). Illustratively, there is some evidence that increased ANS reactivity (e.g., increased systolic blood pressure reactivity or heart rate reactivity) is associated with indirect aggression in girls, whereas decreased ANS reactivity (e.g., blunted heart rate reactivity and blunted parasympathetic withdrawal) may be associated with direct aggression in boys and girls, respectively ( Murray-Close & Crick, 2007 ; Sijtsema et al., 2011 ).

Further, within direct and indirect aggression, theoretical and empirical evidence suggests two unique subtypes: proactive and reactive aggression ( Little et al., 2003 ; Poulin & Boivin, 2000 ; Stanford et al., 2003 ). Proactive aggression includes behaviors perpetrated for the purpose of gaining resources or control over others (and may or may not occur in response to specific provocation); conversely, reactive aggression involves behavioral responses that arise following a perceived threat or provocation ( Teten et al., 2011 ). Although proactive and reactive aggression can co-occur, they serve different functions and are associated with unique patterns of physiological reactivity ( Babcock, Tharp, Sharp, Heppner, & Stanford, 2014 ; Bobadilla, Wampler, & Taylor, 2012 ; Hubbard et al., 2002 ; Murray-Close & Rellini, 2012 ). A recent investigation of the biological underpinnings of reactive and proactive indirect aggression offers the most comprehensive and compelling evidence in young adults to date ( Murray-Close, Holterman, Breslend, & Sullivan, 2017 ). Utilizing a standardized social stress task, they found that blunted withdrawal of the PNS during stress (i.e., vagal augmentation) predicted proactive relational aggression, and greater SNS reactivity (changes in skin conductance) predicted reactive relational aggression. They also found that vagal augmentation was most likely to predict any form of aggression if the individual also exhibited low skin conductance reactivity.

Murray-Close et al. (2017) made a significant contribution to the field owing to their examination of different forms of stress (cognitive and social) and different forms of aggression, as well as the testing of interactions between multiple arms of the ANS. The current investigation furthers our understanding by employing an ecologically-valid stress task that involves social conflict (thus making it more relevant to aggression and frustration), and drawing upon a more ethnically diverse sample. Latina and African-American women may be three times as likely as White women to experience victimization and two times more likely to engage in aggression toward intimate partners ( Field & Caetano, 2005 ); however, very limited empirical research has focused on aggression in women of color, particularly during the period of young adulthood ( Goldstein, 2011 ; Rivera-Maestre, 2014 ). In addition, in the current work, we consider a factor known to exert a critical influence on the development of aggressive behavior: qualities of the early childhood family environment.

1.2. The role of the childhood family environment

Theories of diathesis-stress and differential susceptibility argue that connections between biology and behavior cannot be understood without considering environmental context early in life ( Ellis, Boyce, Belsky, Bakermans-Kranenburg, & van Ijzendoorn, 2011 ); a substantive body of research supports this claim (see review in Bush & Boyce, 2014 ). These models posit that complex interactions between stress reactivity and social experiences early in life underlie the emergence and maintenance of psychopathology. As outlined above, the majority of studies that have examined the associations between physiological stress reactivity and aggression have not assessed individuals’ history of trauma or quality of the childhood family environment ( Bohnke, Bertsch, Kruk, & Naumann, 2010 ; Gordis, Granger, Susman, & Trickett, 2006 ; Lorber, 2004 ; Patrick & Verona, 2007 ; Verona & Kilmer, 2007 ; Verona & Sullivan, 2008 ), though there are a few exceptions ( El-Sheikh, Hinnant, & Erath, 2011 ; Obradović, Bush, & Boyce, 2011 ; Saxbe, Margolin, Spies Shapiro, & Baucom, 2012 ).

Despite the strong theoretical and empirical foundation supporting biopsychosocial models of disordered behavior and extensive evidence that individuals raised in aggressive households have a greater risk of developing aggressive behavior patterns later in life ( Cui, Durtschi, Donnellan, Lorenz, & Conger, 2010 ; Herrenkohl & Herrenkohl, 2007 ), we could identify only a single study that tested a biopsychosocial model of aggression in young adults, specifically. It was found that vagal withdrawal (i.e. PNS reactivity) was positively associated with reactive aggression and negatively associated with proactive aggression in conditions of “low social adversity” (e.g., less poverty, lack of parental incarceration, uncrowded home, smaller family) ( Zhang & Gao, 2015 ). This study provides compelling preliminary evidence of important environmental influences on the association between stress reactivity in response to a non-social task and different forms of aggression in an ethnically diverse, yet relatively small (n = 84), sample of young adults.

1.3. The current study

The present study extends the existing base of research in a number of important ways. Specifically, the present study 1) utilizes multiple channels of ANS reactivity in reaction to a stressor; 2) employs differentiated measures of aggression (reactive direct, proactive direct, reactive indirect, and proactive indirect); 3) includes an ethnically-diverse female sample; and 4) includes reports of childhood family conflict in order to test moderating effects. Taken together, the current investigation will be the first study to involve a sophisticated test of the associations between physiological reactivity to stress, relevant developmental experiences, and aggressive behavior outcomes in population that is at elevated risk for aggression yet is underrepresented in the literature. Such an investigation may help to resolve the inconsistent findings in the field regarding associations between psychophysiology and aggression by considering direct associations between each branch of the ANS in the context of childhood exposure to family conflict, while controlling for the other branch of the ANS.

Based on prior examinations of the biological underpinnings of delinquency in children from high conflict families ( El-Sheikh et al., 2011 ) and models of differential susceptibility ( Bush & Boyce, 2014 ), we posited that blunted SNS reactivity to stress will be associated with greater proactive aggression and heightened SNS reactivity will be associated with greater reactive aggression among women exposed to higher levels of family conflict earlier in life, while controlling for PNS activity. We also hypothesized that blunted PNS reactivity (vagal augmentation) and greater PNS reactivity (vagal withdrawal) would be associated with greater proactive and reactive aggression, respectively, among women exposed to higher family conflict while controlling for SNS activity. We had no a priori hypotheses regarding the form of aggression (direct vs. indirect), but based on research with children, we tentatively expected that associations might be stronger for indirect aggression compared to direct aggression given that the sample includes only women and indirect aggression frequency and variability might be higher compared to physical aggression in this population.

2.1. Participants

One hundred seventy-eight female young adults attending a state university or community college in a major city in the Western United States participated in the study. Recruitment procedures included: flyers displayed on bulletin boards and metro lines surrounding the two campuses; scripted announcements in university classrooms; and flyer postings to online and in-person university courses. A special effort was made to recruit women of color by posting on Facebook pages of student groups representing Latinx and Asian students and making announcements in Ethnic Studies-focused courses. Due to the nature of the study, which included neurobiological measures of stress reactivity, eligibility criteria included the following: 18–35 years of age, English speaking, body max index less than 35, without a history of serious medical conditions (particularly heart or respiratory ones), and not taking medications that could interfere with the assessment of stress physiology.

Of the 178 participants who completed the study, nine failed attention check questions and/or did not speak fluent English, and ten participants were missing physiological data due to equipment failure or experimenter error. The final sample for the current analysis included 159 young women (Mean age: 21.6 years, SD = 3.15), including 130 undergraduate students without (52 %) and with (30 %) an Associate’s Degree and 29 master’s students (18 %). The sample was ethnically diverse: 32 % Latina/Hispanic, 27 % Asian/Pacific-Islander, 24 % White, 6% Black, 9% Multi-ethnic, and 3% Other. Of those who reported on parental nativity (n = 150), 50 % indicated that neither parent was born in the United States. The majority of women reported earning less than $10,000 per year (77.4 %).

2.2. Procedures

All procedures were approved by the university Institutional Review Board. Individuals who were interested in participating in the study were directed to an online registration form that included the eligibility criteria. If eligible, participants were instructed 24 h prior to their appointment to refrain from vigorous exercise, smoking, drinking alcohol, coffee/energy drinks, consuming food or cold medicine for at least 2 h before their scheduled lab visit. Appointments were either at 1 pm or 4 pm on a weekday and lasted approximately 2 h. Following the informed consent process, height and weight measurements were taken to calculate body mass index. Participants were then attached to physiological equipment. Following a baseline resting period, the participants completed two conflict discussion role play tasks and rated their mood and cognitive appraisals prior to and following the tasks. After detachment from the physiological sensors, participants completed a battery of questionnaires on a computer located in a room separate from where the stress tasks occurred. Participants were compensated with $25 in the form of an Amazon gift card or extra credit for a psychology course.

2.3. Measures

2.3.1. self-report questionnaires, 2.3.1.1. direct aggression..

Direct aggression was measured using the Reactive-Proactive Questionnaire (RPQ; Raine et al., 2006 ), with slight word modifications to ensure it was appropriate for emerging adults. The RPQ includes a 12-item reactive aggression subscale (e.g., “Yelled at others when they have annoyed you.”) and an 11-item proactive aggression subscale (e.g., “Had fights with others to show who was in control.”). Questions were rated on a scale of 0 (never) , 1 (sometimes) , or 2 ( often) and items on each of the two subscales were averaged, with higher scores reflecting more direct reactive or proactive aggression. Given that the RPQ was originally developed for child populations and measurement models have not been published for normative young adult populations, a confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) was conducted. Results showed that 4 items on the proactive subscale loaded poorly (<.30). These items were removed. Final analyses utilized the full 12-item reactive aggression scale (α = .81) and the reduced 7-item proactive aggression scale (α = .59).

2.3.1.2. Indirect aggression.

Indirect aggression was assessed using the peer-directed aggression subscales of the Self-Report of Aggression and Social Behavioral Measure ( Murray-Close, Ostrov, Nelson, Crick, & Coccaro, 2010 ). The original measure included 13 items assessing peer-directed proactive and reactive indirect aggression; however, the current study utilized the nine items employed in a previous study ( Murray Close et al., 2010 ; α = .81). Four items assess reactive indirect aggression (e.g., “When I am not invited to do something with a group of people, I will exclude those people from future activities.”) and five items assess proactive indirect aggression (e.g., “My friends know that I will think less of them if they do not do what I want them to.”). Items were rated on a scale from 0 ( never ) to 4 ( very often ) and averaged for each subscale, with higher scores reflecting more indirect aggression. Internal consistencies for the reactive and proactive subscales in the current study were .78 and .65, respectively.

2.3.1.3. Family conflict in childhood.

The Risky Family Environment questionnaire is a 13- item self-report measure that assesses aspects of the childhood family environment, such as chaos, predictability, warmth, and conflict ( Taylor, Lerner, Sage, Lehman, & Seeman, 2004 ). Participants indicated how true each statement was for them on a scale from 1 ( not at all ) to 5 ( very often ). For the current study, only the 7 conflict items were used (e.g., “How often did a parent or other adult in the household push, grab, shove, or slap you?”; α = .81).

2.4. Social conflict paradigm

2.4.1. role play tasks.

Participants completed two 5-minute role play tasks ( Larkin, Semenchuk, Frazer, Suchday, & Taylor, 1998 ), the order of which was counterbalanced across the sample. For each task, a trained confederate entered the room and sat facing directly across from the participant approximately 30 in. away. All confederates were instructed to display a neutral facial expression, maintain flat affect, make direct eye contact, and not engage with the participant outside of their assigned lines. In the Messy Roommate roleplay, participants interacted with a female confederate in a role play scenario in which participants were instructed to act out the following: “Your roommate is a slob and the apartment is a mess. You always do your share. You ask her to do the dishes because you have friends coming over. You get back home and the place is worse than when you left it. Your goal is to get your roommate to agree to clean up the apartment.” In the Noisy Neighbor role play task, participants interacted with a male confederate in a role play scenario in which participants were instructed to act out the following: “You are trying to study for an important exam. You really need to do well on this exam, but you can’t concentrate because your neighbor is playing his music too loud. You decide to ask him to turn down his music so you can study.”

2.4.2. Mood and cognitive appraisals

Participants’ negative mood and negative appraisals of the tasks were assessed prior to and following the role play tasks. The Positive and Negative Affect Schedule is a 20-item self-report measure that assesses current positive and negative affect (PANAS; Watson, Clark, & Tellegen, 1988 ). Participants indicated how much they currently felt each state on a scale from 1 ( not at all ) to 5 ( extremely ). Only the 10-item Negative Subscale was used in the current study (α = .83). The Stress Appraisal Measure is a 28-item self-report measure that assesses an individual’s appraisal of a specific stressful situation ( Peacock & Wong, 1990 ). Participants indicated how they felt about the situation on a scale from 1 ( not at all ) to 5 ( extremely) . Only the 4-item Threat Subscale was used in the current study (α = .70). These measures served as a manipulation check for the social stress tasks.

2.5. Physiological measurements

Autonomic Nervous System (ANS) stress reactivity was recorded using electrocardiography (ECG) and impedance cardiography (ICG) with BIOPAC (Biopac MP150, Data Acquisition System, Biopac Systems, Inc., www.biopac.com ). The experimenter applied two strips of impedance tape around the circumference of participants’ necks with its mylar 3 cm apart from each other and parallel to the ground. In a similar fashion two other strips were applied around the torso, right below the bra line. Two ECG electrodes were then placed, one on the right breastbone and the other under the left rib cage, slightly above the belly button. Data were sampled at 1000 Hz.

There were a total of four relevant consecutive recording sessions: Baseline, Social Stress task 1, Social Stress task 2 and Recovery, each five minutes long for a total of 20 min of recording per participant. Data was cleaned using Mindware HRV and IMP v3.0.15 by visually inspecting each 1-minute segment for artifacts and edited when needed. Segments in which more than 10 % of the data were missing were excluded from analyses. Minute segments were averaged together for each recording session to create a single mean score per session.

We focused specifically on Pre-Ejection Period (PEP; a time-based measure that is determined as the time from the left ventricle contracting to the opening of the aortic valve) and Respiratory Sinus Arrhythmia (RSA; a type of heart rate variability in which spectral analysis is used to derive the high frequency component of the interbeat Interval cycle (0.12 to 0.40 hz)) because they have been known to assess activation of the sympathetic and parasympathetic systems, respectively. Studies using pharmacological blockades have shown that PEP measures cardiac sympathetic activation without the influence of the vagus nerve ( Berntson et al., 1994 ), and RSA is considered mainly vagally mediated, reflecting cardiac parasympathetic activation without sympathetic input ( Mendes, 2009 ). For PEP, a smaller reactivity score means greater activation of SNS, whereas for RSA, a smaller reactivity score means less activation of PNS, both of which are interpreted as higher stress reactivity.

Paired t-tests contrasting average baseline PEP and average PEP during the first task indicated that PEP values decreased significantly from baseline ( M = 105.54, SD = 10.92) to the end of the first task ( M = 90.87, SD = 15.36), t (157) = 15.65, p < .001, and from baseline to the end of the second task ( M = 93.30, SD = 14.06), t (156) = 13.82, p < .001. RSA values also decreased from baseline ( M = 6.56, SD = 0.97) to the first task ( M = 6.45, SD = 0.90), although statistical significance was marginal, t (157) = 1.74, p = .09. There was no change in RSA values from baseline to the second task, ( M = 6.55, SD = 0.87), t (156) = .12, p = .91. PEP change from baseline to the first task was statistically significantly greater than PEP change from baseline to the second task ( M diff = −2.44, t = −5.13, p < .0001). Additionally, RSA change from baseline to the first task was also greater than RSA change from baseline to the second task ( M diff = −0.11, t = −3.26, p = .001). We interpret these differences as evidence of habituation to the second task. Thus, reactivity scores to be used in the preliminary and primary analyses were calculated by subtracting average PEP and RSA at baseline from average PEP and RSA during the first task, respectively.

2.6. Data analysis

Study variables were inspected for non-normality and outliers. Inspection of aggression and reactivity scores revealed a number of outliers. One case had a direct proactive aggression value above 3*Interquartile Range (IQR) and was winsorized to the next highest value. Two cases had indirect proactive aggression values more than 3*IQR; these values were winsorized to the next highest value. Four individuals had PEP reactivity scores that were 3*IQR and three individuals had RSA reactivity scores that were 3*IQR. These high levels could not be explained by these participants’ body mass index, behavior during the task, or daily use of caffeine, marijuana, or alcohol; therefore, these cases were winsorized to the next highest value and included in the analyses.

Correlational analyses were conducted to examine bivariate relations between the primary study variables and potential covariates, including age, income, and race/ethnicity. Given the ethnic diversity of the sample, we also explored whether the primary variables of interest differed across different ethnic groups. Primary analyses were conducted within a structural equation modeling (SEM) framework in Mplus v.8 using maximum likelihood estimation with robust standard errors, which is appropriate for non-normally distributed data. The SEM framework allowed for the simultaneous estimation of relations between the independent variables (i.e., PEP reactivity, RSA reactivity, and childhood family conflict) and the four different types of aggression: direct reactive, direct proactive, indirect reactive, and indirect proactive aggression. The three independent variables were mean-centered and interaction terms were created by taking the products of PEP reactivity × family conflict and RSA reactivity × family conflict. Specificity analyses were conducted to inspect the influence of a single participant who scored substantially higher on all aggression measures. There was a significant change in multiple coefficients when this participant was excluded, suggesting that this case exerted undue influence on the associations; therefore, all analyses were conducted excluding this one case.

3.1. Preliminary analyses

A manipulation check of the social stress tasks was conducted by examining changes in self-reported mood, self-reported negative cognitive appraisals, and autonomic reactivity to each of the tasks. Paired t-tests indicated a significant increase in negative mood from pre-task ( M = 13.63, SD = 4.67) to post-tasks ( M = 18.30, SD = 6.51), t (157) = −10.92, p < .001 and a significant increase in threat appraisal from pre-task ( M = 1.77, SD = 0.62) to post-tasks ( M = 2.32, SD = 0.88), t (156) = −8.59, p < .001, providing evidence that participants subjectively experienced the tasks as stressful.

Descriptives and zero-order correlations among the variables of interest are displayed in Table 1 . Mean levels of aggression were quite low. In addition, young women endorsed family conflict as happening “rarely” on average; however, 30 % of women reported that family conflict occurred “sometimes” or “often”. Family conflict was associated with greater direct reactive aggression but showed no statistically significant correlation with direct proactive aggression or either form of indirect aggression. Family conflict was also correlated with greater RSA reactivity (i.e., more parasympathetic withdrawal). Income and age were not statistically significantly correlated with any of the primary variables ( p s > .10, not shown). In addition to the expected positive associations among all aggression indicators, there was also a small but statistically significant positive correlation between PEP reactivity and RSA reactivity. The small to moderate correlations between the different types of direct and indirect aggression indicate the value of examining these as separate outcomes.

Kendall’s Tau Correlations.

| M (SD) | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Family Conflict | 2.70 (.82) | ||||||

| 2. PEP Reactivity | −14.47 (11.23) | −.03 | |||||

| 3. RSA Reactivity | −.11 (.78) | −.13 | .17 | ||||

| 4. Direct Reactive | .67 (.34) | .19 | −.08 | .02 | |||

| 5. Direct Proactive | .12 (.16) | .05 | −.04 | .004 | .42 | ||

| 6. Indirect Reactive | .52 (.61) | .07 | −.04 | .02 | .36 | .36 | |

| 7. Indirect Proactive | .35 (.42) | −.02 | −.03 | .08 | .27 | .32 | .44 |

Note : Negative RSA and PEP reactivity values = more reactivity so the negative correlation between PEP reactivity and reactive aggression is interpreted such that more PEP reactivity is associated with more aggression.

To explore whether the primary variables of interest differed across ethnicity, four groups were created based on previous research showing differing levels of aggression in White, Asian, and Latina populations. Due to the low proportion of African-American women (n = 9) and other race/ethnicities (e.g., American Indian/Native American/Indigenous) in the current sample, they were collapsed into a fourth “other” category. History of family conflict did not differ across the groups ( p = .84). In addition, regardless of type or form, aggression did not differ across the four groups ( p s .12–.92). Finally, although PEP reactivity also did not differ across race/ethnicity ( p = .21), RSA reactivity was significantly greater (more parasympathetic withdrawal indicated by larger decreases in RSA values) for women who identified as Latina compared to White women ( M diff = −.453, p = .04).

3.2. Primary analyses

Results are displayed in Table 2 , organized by type of aggression.

PEP reactivity interacting with family conflict (Conflict*PEP) and RSA reactivity interacting with family conflict (Conflict*RSA): Standardized estimates and standard errors.

| Direct Aggression | Indirect Aggression | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Reactive | Proactive | Reactive | Proactive | |||||

| Family Conflict | .071 | .089 | .084 | .095 | .075 | .044 | .074 | |

| RSA reactivity | .076 | −.005 | .089 | .095 | .091 | .099 | .106 | |

| PEP reactivity | − | .073 | −.027 | .071 | −.154 | .083 | −.052 | .074 |

| Conflict PEP | −.124 | .069 | − | .083 | −.056 | .108 | −.162 | .074 |

| Conflict RSA | .065 | .131 | .082 | .062 | .082 | −.039 | .091 | |

3.2.1. Direct reactive aggression

Greater RSA augmentation (less parasympathetic withdrawal), greater PEP reactivity, and greater family conflict all predicted greater direct reactive aggression. However, these associations must be qualified given the statistically significant interaction between RSA reactivity and family conflict ( p = .038; Table 2 ). Simple slopes at +1 SD and −1 SD were estimated and tested following guidelines by Aiken and West (1991) using Mplus and plotted using the PROCESS Macro in SPSS. As shown in Fig. 1 , at high levels of family conflict (+1 SD ), greater RSA augmentation (i.e., less parasympathetic withdrawal, indicated by increased RSA) was associated with higher endorsement of direct reactive aggression, β = .23, SE = .11, p = .03. At low levels of family conflict (−1 SD ), RSA reactivity was not associated with direct reactive aggression ( p = .55).

RSA reactivity predicting direct reactive aggression at +1/−1 SD and mean levels of childhood family conflict.

3.2.2. Direct proactive aggression

The interaction between PEP reactivity and family conflict was statistically significant ( p = .007; Table 2 ). Simple slopes at +1 SD and −1 SD were estimated and tested following guidelines by Aiken and West (1991) using Mplus and plotted using the PROCESS Macro in SPSS. Neither simple slope reached conventional levels of statistical significance ( p s > .05); however, this is not unusual in the case of a full cross-over interaction like the one observed here ( Baron & Kenny, 1986 ). As shown in Fig. 2 , at high levels of family conflict (+1 SD ), greater PEP reactivity (i.e., more SNS activation, indicated by decreased PEP) was marginally associated with higher endorsement of direct proactive aggression, β = −.21, SE = .11, p = .06. At low levels of family conflict (−1 SD ), less PEP reactivity was associated with higher endorsement of direct proactive aggression but the effect was not significant, β = .16, SE = .10, p = .10.

PEP reactivity predicting direct proactive aggression at +1/−1 SD and mean levels of childhood family conflict.

3.2.3. Indirect reactive aggression

Neither interaction term was statistically significant, nor were there any main effects of RSA reactivity or family conflict history on indirect reactive aggression. There was a negative association between PEP reactivity and indirect reactive aggression, but this estimate did not reach statistical significance ( p = .07; Table 2 ).

3.2.4. Indirect proactive aggression

The interaction between PEP reactivity and family conflict was marginally significant for indirect proactive aggression ( p = .055; Table 2 ). Although the estimate did not reach statistical significance, simple slopes were tested to explore whether the pattern of the interaction mirrored that found for the direct form of proactive aggression. Greater PEP reactivity (i.e., more SNS activation) was associated with higher endorsement of indirect proactive aggression, β = −.24, SE = .10, p = .019. At low levels of family conflict (−1 SD ), the association between PEP reactivity and indirect proactive aggression was not statistically significant, β = .13, SE = .11, p = .24.

4. Discussion

Research has produced inconsistent and often contrary findings, with both high or low ANS reactivity shown to increase the risk of aggressive behavior. Although childhood exposure to family conflict is known to predict aggression later in life, few investigations have examined how family history of aggression and biological processes work together in a dynamic fashion to increase the risk of aggressive behavior, particularly among ethnically-diverse female populations. To address this gap, the current study tested whether childhood family conflict exposure moderated associations between physiological responses to social conflict and different forms of aggression (direct and indirect, reactive and proactive) in an ethnically-diverse sample of young adult females. In doing so, the investigation represents a sophisticated test of the associations between physiological reactivity to stress, relevant developmental experiences, and aggressive behavior outcomes in population that may be at elevated risk for aggression yet is underrepresented in the literature.

First, it was expected that, among women exposed to higher levels of family conflict earlier in life, blunted SNS reactivity to stress would be associated with greater proactive aggression, whereas heightened SNS reactivity would be associated with greater reactive aggression, while controlling for PNS reactivity. Family conflict moderated the association between SNS reactivity and proactive aggression only. Contrary to expectations, heightened SNS reactivity was associated with higher levels of direct proactive aggression among women exposed to high levels of family conflict. This finding is consistent with recent work showing that heightened baseline SNS arousal was associated with greater proactive aggression in young adult women (e.g., Armstrong et al., 2019 ), but suggests that family conflict exposure represents a critical contextual variable. The role of family conflict in the psychophysiology of proactive aggression is in line with differential susceptibility models of psychological problems, whereby individuals with heightened sensitivity to context are expected to develop particularly problematic behaviors under conditions of adversity. The lack of a correlation between SNS reactivity and family conflict history suggests that heightened sympathetic reactivity did not develop as a result of exposure to conflict. However, given the cross-sectional nature of the study, it is not possible to conclude that young women’s pattern of physiological responses were also evident earlier in life.

The association between heightened SNS reactivity and greater proactive aggression for women exposed to family conflict contrasts with previous findings of the opposite association among young women who experienced sexual abuse ( Murray-Close & Rellini, 2012 ). Although sexual abuse may exert a unique effect compared to exposure to family conflict, a number of differences between the two investigations may also account for the divergence in findings, including but not limited to the characteristics of the samples (the present study included an extremely diverse and larger sample of women), the measure of SNS (in the previous study, heart rate reactivity was used as an indicator of ANS response, which captures both sympathetic and parasympathetic influences) and the use of different stress tasks (the previous study employed a social stress interview). The use of an ecologically-valid social stress task in the current study is a unique strength given that stress reactivity to social conflict may be especially salient for those who have been exposed to family conflict.

The current study adds to the growing body of research implicating particular physiological patterns in the expression of different types of aggression, regardless of family history of aggression. It revealed direct associations between each branch of the ANS and multiple measures of aggression while controlling for the other branch of the ANS. This approach contrasts with the common practice of examining biological processes in isolation and is consistent with how these systems actually function in co-ordination within the individual. Consistent with previous research ( Hubbard et al., 2002 ; Murray-Close & Rellini, 2012 ), heightened SNS reactivity was related to significantly greater direct reactive and marginally indirect reactive aggression, suggesting that women who endorsed the use of reactive aggression became more physiologically activated, particularly in terms of the SNS fight-or-flight response, during social conflict. Reactive aggression may be a behavioral product of the high levels of physiological stress arousal these women experience when faced with perceived antagonism from others. The current study cannot elucidate causal relations, however. It may also be that a history of responding to others with reactive aggression has led to increased levels of physiological activation in response to conflict for these women. Future research employing a longitudinal design could help unpack potential causal pathways.

The association between RSA reactivity and aggression was confined to the reactive form of direct aggression only, was in the opposite direction of expectations, and was strongest for women who reported high levels of family conflict. Lower RSA reactivity or vagal augmentation (indicative of a blunted stress response whereby the PNS does not withdraw as expected) was associated with endorsement of greater direct reactive aggression, except for women who reported low levels of family conflict. This finding contrasts with preliminary evidence for an association between higher RSA reactivity (i.e., greater vagal withdrawal) and reactive aggression among young adults who reported experiencing low levels of social adversity ( Zhang & Gao, 2015 ). Because we included both branches of the ANS in the same model we see that PNS activation was accompanied by greater SNS activation (i.e., greater PEP reactivity), which is a state referred to as ANS coactivation ( Berntson, Cacioppo, & Quigley, 1991 ). As described by Murray-Close et al. (2017) , both heightened SNS responses to stress and heightened PNS responses (vagal augmentation) to stress are associated with strong or poorly regulated experiences of negative emotion, which may then lead to aggression. Our work indicates that ANS coactivation may be a physiological marker for direct reactive aggression in ethnically-diverse young adult women, especially those exposed to high family conflict.

The present findings must be considered in light of study limitations. Recent research has revealed complicated associations between aggression or aggression-related disorders and interactions between the PNS and SNS. For example, young adults who exhibit low sympathetic reactivity combined heightened parasympathetic reactivity (vagal withdrawal) show greater levels of relational or indirect aggression ( Murray-Close et al., 2017 ). The sample size of the present study did not have sufficient power to test a three-way interaction; future research involving significantly larger samples of participants should consider testing whether history of family conflict or childhood maltreatment influences mutli-system stress profiles associated with different forms of aggression. Additionally, although well-validated measures of direct and indirect measures of aggression were used in the current study, the internal consistency for the measures of proactive forms of aggression were relatively low. Notably, however, the interaction between family conflict and PEP reactivity was present for the two different measures of proactive aggression, adding confidence to the finding. The lower internal consistency observed in the proactive aggression measures may be a result of the lower endorsement of proactive aggression in this population. In fact, overall levels of aggression regardless of form or type appeared to be relatively lower in these women compared to other studies of female aggression (e.g., Dinić & Wertag, 2018 ; Morel, Haden, Meehan, & Papouchis, 2018 ). Thus, our findings indicate the SNS responses and a history of family conflict are important factors for understanding relatively low, non-clinical levels of aggression.

The current study also has a number of strengths. It advances the field by focusing on a developmental period often overlooked in investigations of aggression. Past research on aggression (as well as prevention/intervention programs) has focused predominately on children and adolescents ( Crick & Dodge, 1996 ) (or on adults with psychiatric disorder; Howells, Daffern, & Day, 2008 ). However, the majority of at-risk youth do not have access to effective interventions ( Mihalopoulos, Vos, Pirkis, & Carter, 2011 ), which means these same youth enter subsequent developmental stages without having had any corrective interpersonal experiences. Indeed, young adulthood is the most at-risk age group for exhibiting extreme aggressive behaviors, such as homicide ( U.S. Department of Justice, 2009 ), and interpersonal violence disproportionately occurs in young adulthood compared to other developmental stages ( Kim, Laurent, Capaldi, & Feingold, 2008 ). As such, young adulthood a critical time to interrupt the intergenerational transmission of aggression. Our findings demonstrate the importance of assessing the influences of multiple physiological systems on outcomes simultaneously as well as the need to consider the role of developmental history to more fully understand relationships between physiology and behavior. The identification of biological markers associated with different forms of aggression in diverse young women helps inform the development of prevention programs to break the intergenerational transmission of violent behavior in an under-studied and under-served population.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by grants from the San Francisco State University (SFSU) Office of Research and Sponsored Programs and the National Institute of Health Building Infrastructure Leading to Diversity (BUILD) Initiative (UL1GM118985).

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest to report.

- Aiken LS, & West SG (1991). Multiple regression: Testing and interpreting interactions . Newbury Park, CA: Sage Publications. [ Google Scholar ]

- Anderson CA, & Bushman BJ (2002). Human aggression . Annual Review of Psychology , 53 , 27–51. 10.1146/annurev.psych.53.100901.135231. [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Armstrong T, Wells J, Boisvert DL, Lewis R, Cooke EM, Woeckener M, & Kavish N (2019). Skin conductance, heart rate and aggressive behavior type . Biological Psychology , 141 (April), 44–51. 10.1016/j.biopsycho.2018.12.012. [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Babcock JC, Tharp ALT, Sharp C, Heppner W, & Stanford MS (2014). Aggression and Violent Behavior Similarities and differences in impulsive / premeditated and reactive / proactive bimodal classi fi cations of aggression . Aggression and Violent Behavior , 19 ( 3 ), 251–262. 10.1016/j.avb.2014.04.002. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Baron RM, & Kenny D (1986). The moderator-mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations . Journal of Personality and Social Psychology , 51 ( 6 ), 1173–1182. 10.1037/0022-3514.51.6.1173. [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Beauchaine TP, Gatzke-Kopp L, & Mead HK (2007). Polyvagal Theory and developmental psychopathology: Emotion dysregulation and conduct problems from pre-school to adolescence . Biological Psychology , 74 ( 2 ), 174–184. 10.1016/j.biopsycho.2005.08.008. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Berntson GG, Cacioppo JT, & Quigley KS (1991). Autonomic determinism: The modes of autonomic control, the doctrine of autonomic space, and the laws of autonomic constraint . Psychological Review , 98 ( 4 ), 459–487. 10.1037/0033-295X.98.4.459. [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Berntson GG, Cacioppo JT, Binkley PF, Uchino BN, Quigley KS, & Fieldstone A (1994). Autonomic cardiac control: III. Psychological stress and cardiac response in autonomic space as revealed by pharmacological blockades . Psychophysiology , 31 ( 6 ), 599–608. 10.1111/j.1469-8986.1994.tb02352.x. [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Bobadilla L, Wampler M, & Taylor J (2012). Proactive and reactive aggression are associated with different physiological and personality profiles . Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology , 31 ( 5 ), 458–487. [ Google Scholar ]

- Bohnke R, Bertsch K, Kruk MR, & Naumann E (2010). The relationship between basal and acute HPA axis activity and aggressive behavior in adults . Journal of Neural Transmission , 117 , 629–637. 10.1007/s00702-010-0391-x. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Bush NR, & Boyce WT (2014). The contribution of early experience to biological development and sensitivity to context In Lewis M, & Rudolph KD (Eds.). Handbook of developmental psychopathology (pp. 287–309). New York: Springer. [ Google Scholar ]

- Calkins SD, Graziano PA, & Keane SP (2007). Cardiac vagal regulation differentiates among children at risk for behavior problems . Biological Psychology , 74 ( 2 ), 144–153. 10.1016/j.biopsycho.2006.09.005. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Crick NR, & Dodge KA (1996). Social information-processing mechanisms on reactive and proactive aggression . Child Development , 67 , 993–1002. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Crick NR, Casas JF, & Mosher M (1997). Relational and overt aggression in pre-school . Developmental Psychology , 33 ( 4 ), 579–588. 10.1037/0012-1649.33.4.579. [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Cui M, Durtschi JA, Donnellan MB, Lorenz FO, & Conger RD (2010). Intergenerational transmission of relationship aggression: A prospective longitudinal stude . Journal of Family Psychology , 24 ( 6 ), 688–697. 10.1037/a0021675.Intergenerational. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Dinić BM, & Wertag A (2018). Effects of Dark Triad and HEXACO traits on reactive/proactive aggression: Exploring the gender differences . Personality and Individual Differences , 123 (September), 44–49. 10.1016/j.paid.2017.11.003. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Ellis BJ, Boyce WT, Belsky J, Bakermans-Kranenburg MJ, & van Ijzendoorn MH (2011). Differential susceptibility to the environment: An evolutionary–Neurodevelopmental theory . Development and Psychopathology , 23 ( 1 ), 7–28. 10.1017/S0954579410000611. [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- El-Sheikh M, Hinnant JB, & Erath S (2011). Developmental trajectories of delinquency symptoms in childhood: The role of marital conflict and autonomic nervous system activity . Journal of Abnormal Psychology , 120 ( 1 ), 16–32. 10.1037/a0020626. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Field C, & Caetano R (2005). Longitudinal model predicting mutual partner violence among White, Black, and Hispanic couples in the United States general population . Violence and Victims , 20 ( 5 ), 499–511. 10.1177/0886260508322181. [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Goldstein SE (2011). Relational aggression in young adults’ friendships and romantic relationships . Personal Relationships , 18 ( 4 ), 645–656. 10.1111/j.1475-6811.2010.01329.x. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Goozen SHM Van Fairchild, G., & Harold GT (2007). The evidence for a neurobiological model of childhood antisocial behavior . Psychological Bulletin , 133 ( 1 ), 149–182. 10.1037/0033-2909.133.1.149. [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Gordis EB, Granger DA, Susman EJ, & Trickett K (2006). Asymmetry between salivary cortisol and alpha-amylase reactivity to stress: Relation to aggressive behavior in adolescents . Psychoneuroendocrinology , 31 , 976–987. 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2006.05.010. [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Herrenkohl TI, & Herrenkohl RC (2007). Examining the overlap and prediction of multiple forms of child maltreatment, stressors, and socioeconomic status: A longitudinal analysis of youth outcomes . Journal of Family Violence , 22 , 553–562. 10.1007/s10896-007-9107-x. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Howells K, Daffern M, & Day A (2008). Aggression and violence The handbook of forensic mental health . London: Taylor & Francis; 351–374. [ Google Scholar ]

- Hubbard JA, Smithmyer CM, Ramsden SR, Elizabeth H, Flanagan KD, Dearing KF, … Simons RF (2002). Observational, physiological, and self-report measures of children’ s anger: Relations to reactive versus proactive aggression73 , 1101–1118. Published by: Wiley on behalf of the Society for Research in Child Development Stable; URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/369(4) . [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Katz LF (2007). Domestic violence and vagal reactivity to peer provocation . Biological Psychology , 74 ( 2 ), 154–164. 10.1016/j.biopsycho.2005.10.010. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Kim HK, Laurent HK, Capaldi DM, & Feingold A (2008). Men’s aggression toward women: A 10-year panel study . Journal of Marriage and the Family , 70 ( 5 ), 1169–1187. 10.1111/j.1741-3737.2008.00558.x. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Larkin KT, Semenchuk EM, Frazer NL, Suchday S, & Taylor RL (1998). Cardiovascular and behavioral response to social confrontation: measuring real-life stress in the laboratory . Annals of Behavioral Medicine , 20 ( 4 ), 294–301 Retrieved from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/10234423 . [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Little TD, Brauner J, Jones SM, Nock MK, Hawley PH, Little TD, … Hawley PH (2003). Rethinking aggression: A typological examination of the functions of aggression . Merrill-Palmer Quarterly , 49 ( 3 ), 343–369. [ Google Scholar ]

- Lorber MF (2004). Psychophysiology of aggression, psychopathy, and conduct problems: A meta-analysis . Psychological Bulletin , 130 ( 4 ), 531–552. 10.1037/0033-2909.130.4.531. [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Mendes WB (2009). Assessing the autonomic nervous system In Harmon-Jones E, & Beers JS (Eds.). Methods in social neuroscience (pp. 118–147). New York: Gilford. [ Google Scholar ]

- Mihalopoulos C, Vos T, Pirkis J, & Carter R (2011). The economic analysis of prevention in mental health programs . Annual Review of Clinical Psychology , 7 , 169–201. 10.1146/annurev-clinpsy-032210-104601. [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Morel KM, Haden SC, Meehan KB, & Papouchis N (2018). Adolescent female aggression: Functions and etiology . Journal of Aggression, Maltreatment and Trauma , 27 ( 4 ), 367–385. 10.1080/10926771.2017.1385047. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Murray-Close D (2013). Psychophysiology of adolescent peer relations I: Theory and research findings . Journal of Research on Adolescence , 23 ( 2 ), 236–259. 10.1111/j.1532-7795.2012.00828.x. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Murray-Close D, & Crick NR (2007). Gender differences in the association between cardiovascular reactivity and aggressive conduct . International Journal of Psychophysiology , 65 , 103–113. 10.1016/j.ijpsycho.2007.03.011. [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Murray-Close D, & Rellini AH (2012). Cardiovascular reactivity and proactive and reactive relational aggression among women with and without a history of sexual abuse . Biological Psychology , 89 ( 1 ), 54–62. 10.1016/j.biopsycho.2011.09.008. [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Murray-Close D, Han G, Cicchetti D, Crick NR, & Rogosch FA (2008). Neuroendocrine regulation and physical and relational aggression: The moderating roles of child maltreatment and gender . Developmental Psychology , 44 ( 4 ), 1160–1176. 10.1037/a0012564. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Murray-Close D, Ostrov JM, Nelson DA, Crick NR, & Coccaro EF (2010). Proactive, reactive, and romantic relational aggression in adulthood: Measurement, predictive validity, gender differences, and association with Intermittent Explosive Disorder . Journal of Psychiatric Research , 44 , 393–404. 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2009.09.005. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Murray-Close D, Holterman LA, Breslend NL, & Sullivan A (2017). Psychophysiology of proactive and reactive relational aggression . Biological Psychology , 130 (September), 77–85. 10.1016/j.biopsycho.2017.10.005. [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Obradović J, Bush NR, Stamperdahl J, Adler NE, & Boyce WT (2010). Biological sensitivity to context: The interactive effects of stress reactivity and family adversity on socioemotional behavior and school readiness . Child Development , 81 ( 1 ), 270–289. 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2009.01394.x. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Obradović J, Bush NR, & Boyce WT (2011). The interactive effect of marital conflict and stress reactivity on externalizing and internalizing symptoms: The role of laboratory stressors . Development and Psychopathology , 23 ( 1 ), 101–114. 10.1017/S0954579410000672. [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Ortiz J, & Raine A (2004). Heart rate level and antisocial behavior in children and adolescents: A meta-analysis . Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry , 43 ( 2 ), 154–162. 10.1097/00004583-200402000-00010. [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Patrick CJ, & Verona E (2007). The psychophysiology of aggression: Autonomic, electrocortical, and neuro-imaging findings In Flannery DJ, Vazsonyi AT, & Waldman ID (Eds.). The Cambridge handbook of violent behavior and aggression (pp. 111–150). Cambridge University Press. [ Google Scholar ]

- Peacock EJ, & Wong PTP (1990). The stress appraisal measure (SAM): A multi-dimensional approach to cognitive appraisal . Stress Medicine , 6 ( 3 ), 227–236. 10.1002/smi.2460060308. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Posthumus JA, Böcker KBE, Raaijmakers MAJ, Van Engeland H, & Matthys W (2009). Heart rate and skin conductance in four-year-old children with aggressive behavior . Biological Psychology , 82 ( 2 ), 164–168. 10.1016/j.biopsycho.2009.07.003. [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Poulin F, & Boivin M (2000). Reactive and proactive aggression: Evidence of a two-factor model . Psychological Assessment , 12 ( 2 ), 115–122. 10.1037/1040-3590.12.2.115. [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Raine A, Dodge K, Loeber R, Gatzke-kopp L, Lynam D, Stouthamer-loeber M, & Liu J (2006). The Reactive-Proactive Aggression Questionnaire: Differential correlates of reactive and proactive aggression in adolescent boys . Aggressive Behavior , 32 ( 2 ), 159–171. 10.1002/ab.20115. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Rivera-Maestre R (2014). Relational aggression narratives of African American and latina young women . Clinical Social Work Journal , 1–14. 10.1007/s10615-014-0474-5. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Saxbe DE, Margolin G, Spies Shapiro LA, & Baucom BR (2012). Does Dampened Physiological Reactivity Protect Youth in Aggressive Family Environments? Child Development , 83 ( 3 ), 821–830. 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2012.01752.x. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Sijtsema JJ, Shoulberg EK, & Murray-Close D (2011). Physiological reactivity and different forms of aggression in girls: Moderating roles of rejection sensitivity and peer rejection . Biological Psychology , 86 ( 3 ), 181–192. 10.1016/j.biopsycho.2010.11.007. [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Stanford MS, Houston RJ, Mathias CW, Villemarette-Pittman NR, Helfritz LE, & Conklin SM (2003). Characterizing aggressive behavior . Assessment , 10 ( 2 ), 183–190. 10.1177/1073191103010002009. [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Taylor SE, Lerner JS, Sage RM, Lehman BJ, & Seeman TEM (2004). Early environment, emotions, responses to stress, and health . Journal of Personality , 72 ( 6 ), 1365–1393. 10.1111/j.1467-6494.2004.00300.x. [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Teten AL, Sharp C, Stanford MS, Lake SL, Raine A, & Kent TA (2011). Correspondence of aggressive behavior classifications among young adults using the Impulsive Premeditated Aggression Scale and the Reactive Proactive Questionnaire . Personality and Individual Differences , 50 , 279–285. 10.1016/j.paid.2010.10.003. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- U.S. Department of Justice, Federal Bureau of Investigation. Crime in the United States . 2009. Retrieved from: https://ucr.fbi.gov/crime-in-the-u.s/2007 .

- Verona E, & Kilmer A (2007). Stress exposure and affective modulation of aggressive behavior in men and women . Journal of Abnormal Psychology , 116 ( 2 ), 410–421. 10.1037/0021-843X.116.2.410. [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Verona E, & Sullivan EA (2008). Emotional catharsis and aggression revisited: Heart rate reduction following aggressive responding . Emotion , 8 ( 3 ), 331–340. 10.1037/1528-3542.8.3.331. [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Watson D, Clark LA, & Tellegen A (1988). Development and validation of brief measures of positive and negative affect: The PANAS scales . Journal of Personality and Social Psychology , 54 ( 6 ), 1063–1070. 10.1037/0022-3514.54.6.1063. [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Zhang W, & Gao Y (2015). Interactive effects of social adversity and respiratory sinus arrhythmia activity on reactive and proactive aggression . Psychophysiology , 52 ( 10 ), 1343–1350. 10.1111/psyp.12473. [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

Family Conflict Resolution: 6 Worksheets & Scenarios (+ PDF)

It is perhaps unrealistic to expect that relationships remain harmonious all the time; occasional disconnections and disagreements are a fact of life that can help a family grow and move forward, accommodating change (Divecha, 2020).

Repeating patterns of conflict, however, can be damaging for family members, especially children, negatively affecting mental and physical wellbeing (Sori, Hecker, & Bachenberg, 2016).

This article explores how to resolve conflict in family relationships and introduces strategies and activities that can help.

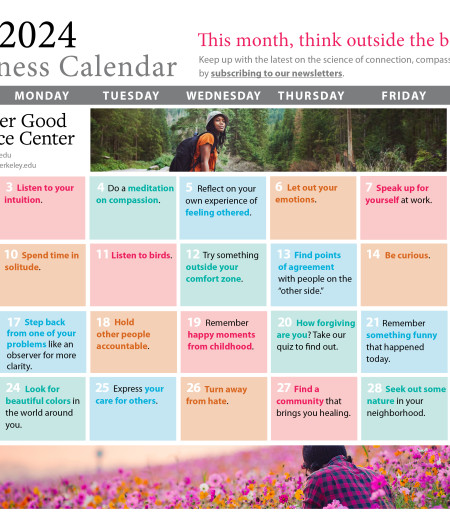

Before you continue, we thought you might like to download our three Positive Communication Exercises (PDF) for free . These science-based tools will help you and those you work with build better social skills and better connect with others.

This Article Contains:

How to resolve conflict in family relationships, 2 examples of conflict scenarios, 3 strategies for family counseling sessions, 6 activities and worksheets to try, a note on conflict resolution for kids, 3 best games and activities for kids, resources from positivepsychology.com, a take-home message.

“Families typically develop certain basic structural characteristics and interactive patterns that they utilize to respond to internal and external stressors.”

Goldenberg, 2017, p. 4

Built on shared assumptions and narratives that exist within the family structure, family members support the group as it adapts and copes with shifting environments and life events.

Such structures, at times, may support and even promote conflict that occurs within families. Indeed, rifts, clashes, and disagreements within the family can take many forms, including physical, verbal, financial, psychological, and sexual (Marta & Alfieri, 2014).

Therapy has the potential to help a family understand how it organizes itself and maintains cohesion, while improving how it communicates and overcomes problems that lead to conflict (Goldenberg, 2017).

As psychologist Rick Hanson writes, “a bid for repair is one of the sweetest and most vulnerable and important kinds of communication that humans offer to each other” (cited in Divecha, 2020).

Crucially, families can learn to navigate the inevitable tension and disconnection that arise from falling out of sync with one another (Divecha, 2020).

Repairing ruptures resulting from miscommunication, mismatches, and failing to attune to one another is vital for parenting and maintaining family union. But how?

While there are many ways to recover from and resolve conflict, the following four steps are invaluable for authentic repair (modified from Divecha, 2020):