Organizing Your Social Sciences Research Assignments

- Annotated Bibliography

- Analyzing a Scholarly Journal Article

- Group Presentations

- Dealing with Nervousness

- Using Visual Aids

- Grading Someone Else's Paper

- Types of Structured Group Activities

- Group Project Survival Skills

- Leading a Class Discussion

- Multiple Book Review Essay

- Reviewing Collected Works

- Writing a Case Analysis Paper

- Writing a Case Study

- About Informed Consent

- Writing Field Notes

- Writing a Policy Memo

- Writing a Reflective Paper

- Writing a Research Proposal

- Generative AI and Writing

- Acknowledgments

Definition and Introduction

Journal article analysis assignments require you to summarize and critically assess the quality of an empirical research study published in a scholarly [a.k.a., academic, peer-reviewed] journal. The article may be assigned by the professor, chosen from course readings listed in the syllabus, or you must locate an article on your own, usually with the requirement that you search using a reputable library database, such as, JSTOR or ProQuest . The article chosen is expected to relate to the overall discipline of the course, specific course content, or key concepts discussed in class. In some cases, the purpose of the assignment is to analyze an article that is part of the literature review for a future research project.

Analysis of an article can be assigned to students individually or as part of a small group project. The final product is usually in the form of a short paper [typically 1- 6 double-spaced pages] that addresses key questions the professor uses to guide your analysis or that assesses specific parts of a scholarly research study [e.g., the research problem, methodology, discussion, conclusions or findings]. The analysis paper may be shared on a digital course management platform and/or presented to the class for the purpose of promoting a wider discussion about the topic of the study. Although assigned in any level of undergraduate and graduate coursework in the social and behavioral sciences, professors frequently include this assignment in upper division courses to help students learn how to effectively identify, read, and analyze empirical research within their major.

Franco, Josue. “Introducing the Analysis of Journal Articles.” Prepared for presentation at the American Political Science Association’s 2020 Teaching and Learning Conference, February 7-9, 2020, Albuquerque, New Mexico; Sego, Sandra A. and Anne E. Stuart. "Learning to Read Empirical Articles in General Psychology." Teaching of Psychology 43 (2016): 38-42; Kershaw, Trina C., Jordan P. Lippman, and Jennifer Fugate. "Practice Makes Proficient: Teaching Undergraduate Students to Understand Published Research." Instructional Science 46 (2018): 921-946; Woodward-Kron, Robyn. "Critical Analysis and the Journal Article Review Assignment." Prospect 18 (August 2003): 20-36; MacMillan, Margy and Allison MacKenzie. "Strategies for Integrating Information Literacy and Academic Literacy: Helping Undergraduate Students make the most of Scholarly Articles." Library Management 33 (2012): 525-535.

Benefits of Journal Article Analysis Assignments

Analyzing and synthesizing a scholarly journal article is intended to help students obtain the reading and critical thinking skills needed to develop and write their own research papers. This assignment also supports workplace skills where you could be asked to summarize a report or other type of document and report it, for example, during a staff meeting or for a presentation.

There are two broadly defined ways that analyzing a scholarly journal article supports student learning:

Improve Reading Skills

Conducting research requires an ability to review, evaluate, and synthesize prior research studies. Reading prior research requires an understanding of the academic writing style , the type of epistemological beliefs or practices underpinning the research design, and the specific vocabulary and technical terminology [i.e., jargon] used within a discipline. Reading scholarly articles is important because academic writing is unfamiliar to most students; they have had limited exposure to using peer-reviewed journal articles prior to entering college or students have yet to gain exposure to the specific academic writing style of their disciplinary major. Learning how to read scholarly articles also requires careful and deliberate concentration on how authors use specific language and phrasing to convey their research, the problem it addresses, its relationship to prior research, its significance, its limitations, and how authors connect methods of data gathering to the results so as to develop recommended solutions derived from the overall research process.

Improve Comprehension Skills

In addition to knowing how to read scholarly journals articles, students must learn how to effectively interpret what the scholar(s) are trying to convey. Academic writing can be dense, multi-layered, and non-linear in how information is presented. In addition, scholarly articles contain footnotes or endnotes, references to sources, multiple appendices, and, in some cases, non-textual elements [e.g., graphs, charts] that can break-up the reader’s experience with the narrative flow of the study. Analyzing articles helps students practice comprehending these elements of writing, critiquing the arguments being made, reflecting upon the significance of the research, and how it relates to building new knowledge and understanding or applying new approaches to practice. Comprehending scholarly writing also involves thinking critically about where you fit within the overall dialogue among scholars concerning the research problem, finding possible gaps in the research that require further analysis, or identifying where the author(s) has failed to examine fully any specific elements of the study.

In addition, journal article analysis assignments are used by professors to strengthen discipline-specific information literacy skills, either alone or in relation to other tasks, such as, giving a class presentation or participating in a group project. These benefits can include the ability to:

- Effectively paraphrase text, which leads to a more thorough understanding of the overall study;

- Identify and describe strengths and weaknesses of the study and their implications;

- Relate the article to other course readings and in relation to particular research concepts or ideas discussed during class;

- Think critically about the research and summarize complex ideas contained within;

- Plan, organize, and write an effective inquiry-based paper that investigates a research study, evaluates evidence, expounds on the author’s main ideas, and presents an argument concerning the significance and impact of the research in a clear and concise manner;

- Model the type of source summary and critique you should do for any college-level research paper; and,

- Increase interest and engagement with the research problem of the study as well as with the discipline.

Kershaw, Trina C., Jennifer Fugate, and Aminda J. O'Hare. "Teaching Undergraduates to Understand Published Research through Structured Practice in Identifying Key Research Concepts." Scholarship of Teaching and Learning in Psychology . Advance online publication, 2020; Franco, Josue. “Introducing the Analysis of Journal Articles.” Prepared for presentation at the American Political Science Association’s 2020 Teaching and Learning Conference, February 7-9, 2020, Albuquerque, New Mexico; Sego, Sandra A. and Anne E. Stuart. "Learning to Read Empirical Articles in General Psychology." Teaching of Psychology 43 (2016): 38-42; Woodward-Kron, Robyn. "Critical Analysis and the Journal Article Review Assignment." Prospect 18 (August 2003): 20-36; MacMillan, Margy and Allison MacKenzie. "Strategies for Integrating Information Literacy and Academic Literacy: Helping Undergraduate Students make the most of Scholarly Articles." Library Management 33 (2012): 525-535; Kershaw, Trina C., Jordan P. Lippman, and Jennifer Fugate. "Practice Makes Proficient: Teaching Undergraduate Students to Understand Published Research." Instructional Science 46 (2018): 921-946.

Structure and Organization

A journal article analysis paper should be written in paragraph format and include an instruction to the study, your analysis of the research, and a conclusion that provides an overall assessment of the author's work, along with an explanation of what you believe is the study's overall impact and significance. Unless the purpose of the assignment is to examine foundational studies published many years ago, you should select articles that have been published relatively recently [e.g., within the past few years].

Since the research has been completed, reference to the study in your paper should be written in the past tense, with your analysis stated in the present tense [e.g., “The author portrayed access to health care services in rural areas as primarily a problem of having reliable transportation. However, I believe the author is overgeneralizing this issue because...”].

Introduction Section

The first section of a journal analysis paper should describe the topic of the article and highlight the author’s main points. This includes describing the research problem and theoretical framework, the rationale for the research, the methods of data gathering and analysis, the key findings, and the author’s final conclusions and recommendations. The narrative should focus on the act of describing rather than analyzing. Think of the introduction as a more comprehensive and detailed descriptive abstract of the study.

Possible questions to help guide your writing of the introduction section may include:

- Who are the authors and what credentials do they hold that contributes to the validity of the study?

- What was the research problem being investigated?

- What type of research design was used to investigate the research problem?

- What theoretical idea(s) and/or research questions were used to address the problem?

- What was the source of the data or information used as evidence for analysis?

- What methods were applied to investigate this evidence?

- What were the author's overall conclusions and key findings?

Critical Analysis Section

The second section of a journal analysis paper should describe the strengths and weaknesses of the study and analyze its significance and impact. This section is where you shift the narrative from describing to analyzing. Think critically about the research in relation to other course readings, what has been discussed in class, or based on your own life experiences. If you are struggling to identify any weaknesses, explain why you believe this to be true. However, no study is perfect, regardless of how laudable its design may be. Given this, think about the repercussions of the choices made by the author(s) and how you might have conducted the study differently. Examples can include contemplating the choice of what sources were included or excluded in support of examining the research problem, the choice of the method used to analyze the data, or the choice to highlight specific recommended courses of action and/or implications for practice over others. Another strategy is to place yourself within the research study itself by thinking reflectively about what may be missing if you had been a participant in the study or if the recommended courses of action specifically targeted you or your community.

Possible questions to help guide your writing of the analysis section may include:

Introduction

- Did the author clearly state the problem being investigated?

- What was your reaction to and perspective on the research problem?

- Was the study’s objective clearly stated? Did the author clearly explain why the study was necessary?

- How well did the introduction frame the scope of the study?

- Did the introduction conclude with a clear purpose statement?

Literature Review

- Did the literature review lay a foundation for understanding the significance of the research problem?

- Did the literature review provide enough background information to understand the problem in relation to relevant contexts [e.g., historical, economic, social, cultural, etc.].

- Did literature review effectively place the study within the domain of prior research? Is anything missing?

- Was the literature review organized by conceptual categories or did the author simply list and describe sources?

- Did the author accurately explain how the data or information were collected?

- Was the data used sufficient in supporting the study of the research problem?

- Was there another methodological approach that could have been more illuminating?

- Give your overall evaluation of the methods used in this article. How much trust would you put in generating relevant findings?

Results and Discussion

- Were the results clearly presented?

- Did you feel that the results support the theoretical and interpretive claims of the author? Why?

- What did the author(s) do especially well in describing or analyzing their results?

- Was the author's evaluation of the findings clearly stated?

- How well did the discussion of the results relate to what is already known about the research problem?

- Was the discussion of the results free of repetition and redundancies?

- What interpretations did the authors make that you think are in incomplete, unwarranted, or overstated?

- Did the conclusion effectively capture the main points of study?

- Did the conclusion address the research questions posed? Do they seem reasonable?

- Were the author’s conclusions consistent with the evidence and arguments presented?

- Has the author explained how the research added new knowledge or understanding?

Overall Writing Style

- If the article included tables, figures, or other non-textual elements, did they contribute to understanding the study?

- Were ideas developed and related in a logical sequence?

- Were transitions between sections of the article smooth and easy to follow?

Overall Evaluation Section

The final section of a journal analysis paper should bring your thoughts together into a coherent assessment of the value of the research study . This section is where the narrative flow transitions from analyzing specific elements of the article to critically evaluating the overall study. Explain what you view as the significance of the research in relation to the overall course content and any relevant discussions that occurred during class. Think about how the article contributes to understanding the overall research problem, how it fits within existing literature on the topic, how it relates to the course, and what it means to you as a student researcher. In some cases, your professor will also ask you to describe your experiences writing the journal article analysis paper as part of a reflective learning exercise.

Possible questions to help guide your writing of the conclusion and evaluation section may include:

- Was the structure of the article clear and well organized?

- Was the topic of current or enduring interest to you?

- What were the main weaknesses of the article? [this does not refer to limitations stated by the author, but what you believe are potential flaws]

- Was any of the information in the article unclear or ambiguous?

- What did you learn from the research? If nothing stood out to you, explain why.

- Assess the originality of the research. Did you believe it contributed new understanding of the research problem?

- Were you persuaded by the author’s arguments?

- If the author made any final recommendations, will they be impactful if applied to practice?

- In what ways could future research build off of this study?

- What implications does the study have for daily life?

- Was the use of non-textual elements, footnotes or endnotes, and/or appendices helpful in understanding the research?

- What lingering questions do you have after analyzing the article?

NOTE: Avoid using quotes. One of the main purposes of writing an article analysis paper is to learn how to effectively paraphrase and use your own words to summarize a scholarly research study and to explain what the research means to you. Using and citing a direct quote from the article should only be done to help emphasize a key point or to underscore an important concept or idea.

Business: The Article Analysis . Fred Meijer Center for Writing, Grand Valley State University; Bachiochi, Peter et al. "Using Empirical Article Analysis to Assess Research Methods Courses." Teaching of Psychology 38 (2011): 5-9; Brosowsky, Nicholaus P. et al. “Teaching Undergraduate Students to Read Empirical Articles: An Evaluation and Revision of the QALMRI Method.” PsyArXi Preprints , 2020; Holster, Kristin. “Article Evaluation Assignment”. TRAILS: Teaching Resources and Innovations Library for Sociology . Washington DC: American Sociological Association, 2016; Kershaw, Trina C., Jennifer Fugate, and Aminda J. O'Hare. "Teaching Undergraduates to Understand Published Research through Structured Practice in Identifying Key Research Concepts." Scholarship of Teaching and Learning in Psychology . Advance online publication, 2020; Franco, Josue. “Introducing the Analysis of Journal Articles.” Prepared for presentation at the American Political Science Association’s 2020 Teaching and Learning Conference, February 7-9, 2020, Albuquerque, New Mexico; Reviewer's Guide . SAGE Reviewer Gateway, SAGE Journals; Sego, Sandra A. and Anne E. Stuart. "Learning to Read Empirical Articles in General Psychology." Teaching of Psychology 43 (2016): 38-42; Kershaw, Trina C., Jordan P. Lippman, and Jennifer Fugate. "Practice Makes Proficient: Teaching Undergraduate Students to Understand Published Research." Instructional Science 46 (2018): 921-946; Gyuris, Emma, and Laura Castell. "To Tell Them or Show Them? How to Improve Science Students’ Skills of Critical Reading." International Journal of Innovation in Science and Mathematics Education 21 (2013): 70-80; Woodward-Kron, Robyn. "Critical Analysis and the Journal Article Review Assignment." Prospect 18 (August 2003): 20-36; MacMillan, Margy and Allison MacKenzie. "Strategies for Integrating Information Literacy and Academic Literacy: Helping Undergraduate Students Make the Most of Scholarly Articles." Library Management 33 (2012): 525-535.

Writing Tip

Not All Scholarly Journal Articles Can Be Critically Analyzed

There are a variety of articles published in scholarly journals that do not fit within the guidelines of an article analysis assignment. This is because the work cannot be empirically examined or it does not generate new knowledge in a way which can be critically analyzed.

If you are required to locate a research study on your own, avoid selecting these types of journal articles:

- Theoretical essays which discuss concepts, assumptions, and propositions, but report no empirical research;

- Statistical or methodological papers that may analyze data, but the bulk of the work is devoted to refining a new measurement, statistical technique, or modeling procedure;

- Articles that review, analyze, critique, and synthesize prior research, but do not report any original research;

- Brief essays devoted to research methods and findings;

- Articles written by scholars in popular magazines or industry trade journals;

- Academic commentary that discusses research trends or emerging concepts and ideas, but does not contain citations to sources; and

- Pre-print articles that have been posted online, but may undergo further editing and revision by the journal's editorial staff before final publication. An indication that an article is a pre-print is that it has no volume, issue, or page numbers assigned to it.

Journal Analysis Assignment - Myers . Writing@CSU, Colorado State University; Franco, Josue. “Introducing the Analysis of Journal Articles.” Prepared for presentation at the American Political Science Association’s 2020 Teaching and Learning Conference, February 7-9, 2020, Albuquerque, New Mexico; Woodward-Kron, Robyn. "Critical Analysis and the Journal Article Review Assignment." Prospect 18 (August 2003): 20-36.

- << Previous: Annotated Bibliography

- Next: Giving an Oral Presentation >>

- Last Updated: Jun 3, 2024 9:44 AM

- URL: https://libguides.usc.edu/writingguide/assignments

Research Paper Analysis: How to Analyze a Research Article + Example

Why might you need to analyze research? First of all, when you analyze a research article, you begin to understand your assigned reading better. It is also the first step toward learning how to write your own research articles and literature reviews. However, if you have never written a research paper before, it may be difficult for you to analyze one. After all, you may not know what criteria to use to evaluate it. But don’t panic! We will help you figure it out!

In this article, our team has explained how to analyze research papers quickly and effectively. At the end, you will also find a research analysis paper example to see how everything works in practice.

- 🔤 Research Analysis Definition

📊 How to Analyze a Research Article

✍️ how to write a research analysis.

- 📝 Analysis Example

- 🔎 More Examples

🔗 References

🔤 research paper analysis: what is it.

A research paper analysis is an academic writing assignment in which you analyze a scholarly article’s methodology, data, and findings. In essence, “to analyze” means to break something down into components and assess each of them individually and in relation to each other. The goal of an analysis is to gain a deeper understanding of a subject. So, when you analyze a research article, you dissect it into elements like data sources , research methods, and results and evaluate how they contribute to the study’s strengths and weaknesses.

📋 Research Analysis Format

A research analysis paper has a pretty straightforward structure. Check it out below!

| This section should state the analyzed article’s title and author and outline its main idea. The introduction should end with a strong , presenting your conclusions about the article’s strengths, weaknesses, or scientific value. | |

| Here, you need to summarize the major concepts presented in your research article. This section should be brief. | |

| The analysis should contain your evaluation of the paper. It should explain whether the research meets its intentions and purpose and whether it provides a clear and valid interpretation of results. | |

| The closing paragraph should include a rephrased thesis, a summary of core ideas, and an explanation of the analyzed article’s relevance and importance. | |

| At the end of your work, you should add a reference list. It should include the analyzed article’s citation in your required format (APA, MLA, etc.). If you’ve cited other sources in your paper, they must also be indicated in the list. |

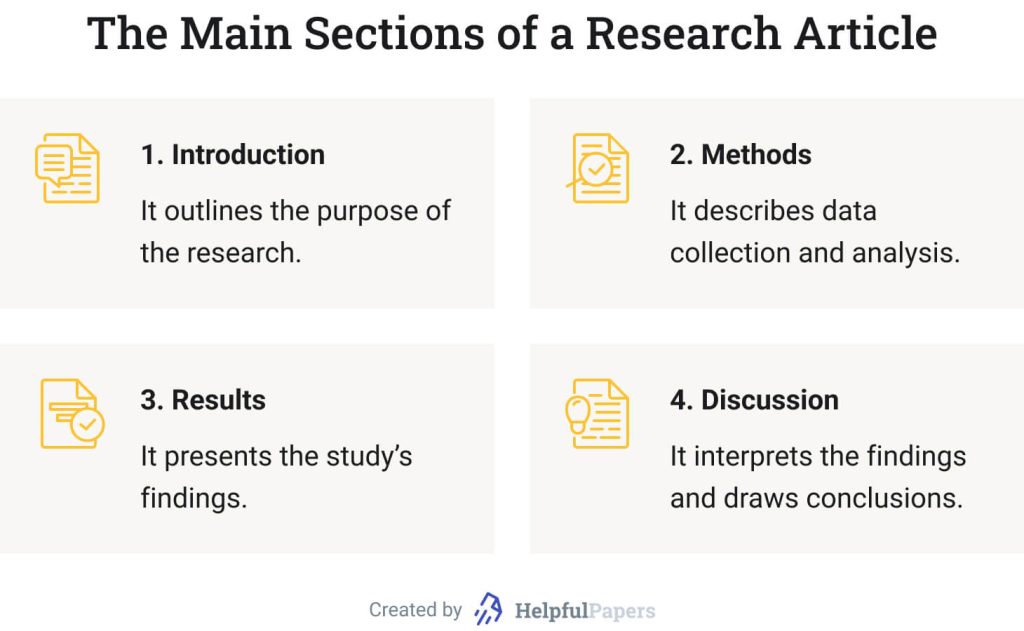

Research articles usually include the following sections: introduction, methods, results, and discussion. In the following paragraphs, we will discuss how to analyze a scientific article with a focus on each of its parts.

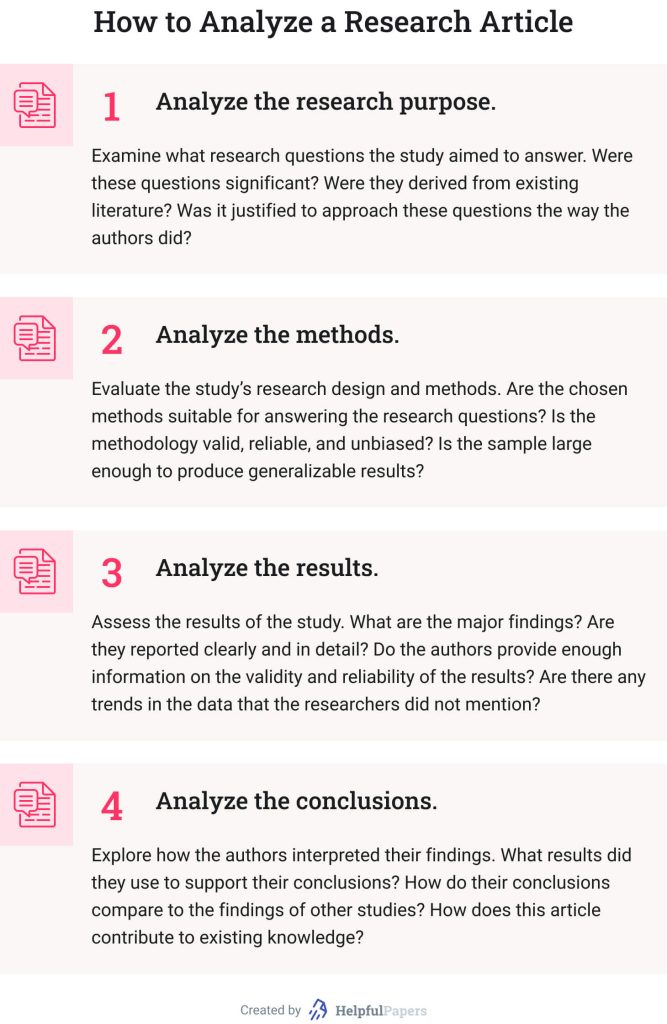

How to Analyze a Research Paper: Purpose

The purpose of the study is usually outlined in the introductory section of the article. Analyzing the research paper’s objectives is critical to establish the context for the rest of your analysis.

When analyzing the research aim, you should evaluate whether it was justified for the researchers to conduct the study. In other words, you should assess whether their research question was significant and whether it arose from existing literature on the topic.

Here are some questions that may help you analyze a research paper’s purpose:

- Why was the research carried out?

- What gaps does it try to fill, or what controversies to settle?

- How does the study contribute to its field?

- Do you agree with the author’s justification for approaching this particular question in this way?

How to Analyze a Paper: Methods

When analyzing the methodology section , you should indicate the study’s research design (qualitative, quantitative, or mixed) and methods used (for example, experiment, case study, correlational research, survey, etc.). After that, you should assess whether these methods suit the research purpose. In other words, do the chosen methods allow scholars to answer their research questions within the scope of their study?

For example, if scholars wanted to study US students’ average satisfaction with their higher education experience, they could conduct a quantitative survey . However, if they wanted to gain an in-depth understanding of the factors influencing US students’ satisfaction with higher education, qualitative interviews would be more appropriate.

When analyzing methods, you should also look at the research sample . Did the scholars use randomization to select study participants? Was the sample big enough for the results to be generalizable to a larger population?

You can also answer the following questions in your methodology analysis:

- Is the methodology valid? In other words, did the researchers use methods that accurately measure the variables of interest?

- Is the research methodology reliable? A research method is reliable if it can produce stable and consistent results under the same circumstances.

- Is the study biased in any way?

- What are the limitations of the chosen methodology?

How to Analyze Research Articles’ Results

You should start the analysis of the article results by carefully reading the tables, figures, and text. Check whether the findings correspond to the initial research purpose. See whether the results answered the author’s research questions or supported the hypotheses stated in the introduction.

To analyze the results section effectively, answer the following questions:

- What are the major findings of the study?

- Did the author present the results clearly and unambiguously?

- Are the findings statistically significant ?

- Does the author provide sufficient information on the validity and reliability of the results?

- Have you noticed any trends or patterns in the data that the author did not mention?

How to Analyze Research: Discussion

Finally, you should analyze the authors’ interpretation of results and its connection with research objectives. Examine what conclusions the authors drew from their study and whether these conclusions answer the original question.

You should also pay attention to how the authors used findings to support their conclusions. For example, you can reflect on why their findings support that particular inference and not another one. Moreover, more than one conclusion can sometimes be made based on the same set of results. If that’s the case with your article, you should analyze whether the authors addressed other interpretations of their findings .

Here are some useful questions you can use to analyze the discussion section:

- What findings did the authors use to support their conclusions?

- How do the researchers’ conclusions compare to other studies’ findings?

- How does this study contribute to its field?

- What future research directions do the authors suggest?

- What additional insights can you share regarding this article? For example, do you agree with the results? What other questions could the researchers have answered?

Now, you know how to analyze an article that presents research findings. However, it’s just a part of the work you have to do to complete your paper. So, it’s time to learn how to write research analysis! Check out the steps below!

1. Introduce the Article

As with most academic assignments, you should start your research article analysis with an introduction. Here’s what it should include:

- The article’s publication details . Specify the title of the scholarly work you are analyzing, its authors, and publication date. Remember to enclose the article’s title in quotation marks and write it in title case .

- The article’s main point . State what the paper is about. What did the authors study, and what was their major finding?

- Your thesis statement . End your introduction with a strong claim summarizing your evaluation of the article. Consider briefly outlining the research paper’s strengths, weaknesses, and significance in your thesis.

Keep your introduction brief. Save the word count for the “meat” of your paper — that is, for the analysis.

2. Summarize the Article

Now, you should write a brief and focused summary of the scientific article. It should be shorter than your analysis section and contain all the relevant details about the research paper.

Here’s what you should include in your summary:

- The research purpose . Briefly explain why the research was done. Identify the authors’ purpose and research questions or hypotheses .

- Methods and results . Summarize what happened in the study. State only facts, without the authors’ interpretations of them. Avoid using too many numbers and details; instead, include only the information that will help readers understand what happened.

- The authors’ conclusions . Outline what conclusions the researchers made from their study. In other words, describe how the authors explained the meaning of their findings.

If you need help summarizing an article, you can use our free summary generator .

3. Write Your Research Analysis

The analysis of the study is the most crucial part of this assignment type. Its key goal is to evaluate the article critically and demonstrate your understanding of it.

We’ve already covered how to analyze a research article in the section above. Here’s a quick recap:

- Analyze whether the study’s purpose is significant and relevant.

- Examine whether the chosen methodology allows for answering the research questions.

- Evaluate how the authors presented the results.

- Assess whether the authors’ conclusions are grounded in findings and answer the original research questions.

Although you should analyze the article critically, it doesn’t mean you only should criticize it. If the authors did a good job designing and conducting their study, be sure to explain why you think their work is well done. Also, it is a great idea to provide examples from the article to support your analysis.

4. Conclude Your Analysis of Research Paper

A conclusion is your chance to reflect on the study’s relevance and importance. Explain how the analyzed paper can contribute to the existing knowledge or lead to future research. Also, you need to summarize your thoughts on the article as a whole. Avoid making value judgments — saying that the paper is “good” or “bad.” Instead, use more descriptive words and phrases such as “This paper effectively showed…”

Need help writing a compelling conclusion? Try our free essay conclusion generator !

5. Revise and Proofread

Last but not least, you should carefully proofread your paper to find any punctuation, grammar, and spelling mistakes. Start by reading your work out loud to ensure that your sentences fit together and sound cohesive. Also, it can be helpful to ask your professor or peer to read your work and highlight possible weaknesses or typos.

📝 Research Paper Analysis Example

We have prepared an analysis of a research paper example to show how everything works in practice.

No Homework Policy: Research Article Analysis Example

This paper aims to analyze the research article entitled “No Assignment: A Boon or a Bane?” by Cordova, Pagtulon-an, and Tan (2019). This study examined the effects of having and not having assignments on weekends on high school students’ performance and transmuted mean scores. This article effectively shows the value of homework for students, but larger studies are needed to support its findings.

Cordova et al. (2019) conducted a descriptive quantitative study using a sample of 115 Grade 11 students of the Central Mindanao University Laboratory High School in the Philippines. The sample was divided into two groups: the first received homework on weekends, while the second didn’t. The researchers compared students’ performance records made by teachers and found that students who received assignments performed better than their counterparts without homework.

The purpose of this study is highly relevant and justified as this research was conducted in response to the debates about the “No Homework Policy” in the Philippines. Although the descriptive research design used by the authors allows to answer the research question, the study could benefit from an experimental design. This way, the authors would have firm control over variables. Additionally, the study’s sample size was not large enough for the findings to be generalized to a larger population.

The study results are presented clearly, logically, and comprehensively and correspond to the research objectives. The researchers found that students’ mean grades decreased in the group without homework and increased in the group with homework. Based on these findings, the authors concluded that homework positively affected students’ performance. This conclusion is logical and grounded in data.

This research effectively showed the importance of homework for students’ performance. Yet, since the sample size was relatively small, larger studies are needed to ensure the authors’ conclusions can be generalized to a larger population.

🔎 More Research Analysis Paper Examples

Do you want another research analysis example? Check out the best analysis research paper samples below:

- Gracious Leadership Principles for Nurses: Article Analysis

- Effective Mental Health Interventions: Analysis of an Article

- Nursing Turnover: Article Analysis

- Nursing Practice Issue: Qualitative Research Article Analysis

- Quantitative Article Critique in Nursing

- LIVE Program: Quantitative Article Critique

- Evidence-Based Practice Beliefs and Implementation: Article Critique

- “Differential Effectiveness of Placebo Treatments”: Research Paper Analysis

- “Family-Based Childhood Obesity Prevention Interventions”: Analysis Research Paper Example

- “Childhood Obesity Risk in Overweight Mothers”: Article Analysis

- “Fostering Early Breast Cancer Detection” Article Analysis

- Space and the Atom: Article Analysis

- “Democracy and Collective Identity in the EU and the USA”: Article Analysis

- China’s Hegemonic Prospects: Article Review

- Article Analysis: Fear of Missing Out

- Codependence, Narcissism, and Childhood Trauma: Analysis of the Article

- Relationship Between Work Intensity, Workaholism, Burnout, and MSC: Article Review

We hope that our article on research paper analysis has been helpful. If you liked it, please share this article with your friends!

- Analyzing Research Articles: A Guide for Readers and Writers | Sam Mathews

- Summary and Analysis of Scientific Research Articles | San José State University Writing Center

- Analyzing Scholarly Articles | Texas A&M University

- Article Analysis Assignment | University of Wisconsin-Madison

- How to Summarize a Research Article | University of Connecticut

- Critique/Review of Research Articles | University of Calgary

- Art of Reading a Journal Article: Methodically and Effectively | PubMed Central

- Write a Critical Review of a Scientific Journal Article | McLaughlin Library

- How to Read and Understand a Scientific Paper: A Guide for Non-scientists | LSE

- How to Analyze Journal Articles | Classroom

How to Write an Animal Testing Essay: Tips for Argumentative & Persuasive Papers

Descriptive essay topics: examples, outline, & more.

Writing a Critical Analysis

What is in this guide, definitions, putting it together, tips and examples of critques.

- Background Information

- Cite Sources

Library Links

- Ask a Librarian

- Library Tutorials

- The Research Process

- Library Hours

- Online Databases (A-Z)

- Interlibrary Loan (ILL)

- Reserve a Study Room

- Report a Problem

This guide is meant to help you understand the basics of writing a critical analysis. A critical analysis is an argument about a particular piece of media. There are typically two parts: (1) identify and explain the argument the author is making, and (2), provide your own argument about that argument. Your instructor may have very specific requirements on how you are to write your critical analysis, so make sure you read your assignment carefully.

Critical Analysis

A deep approach to your understanding of a piece of media by relating new knowledge to what you already know.

Part 1: Introduction

- Identify the work being criticized.

- Present thesis - argument about the work.

- Preview your argument - what are the steps you will take to prove your argument.

Part 2: Summarize

- Provide a short summary of the work.

- Present only what is needed to know to understand your argument.

Part 3: Your Argument

- This is the bulk of your paper.

- Provide "sub-arguments" to prove your main argument.

- Use scholarly articles to back up your argument(s).

Part 4: Conclusion

- Reflect on how you have proven your argument.

- Point out the importance of your argument.

- Comment on the potential for further research or analysis.

- Cornell University Library Tips for writing a critical appraisal and analysis of a scholarly article.

- Queen's University Library How to Critique an Article (Psychology)

- University of Illinois, Springfield An example of a summary and an evaluation of a research article. This extended example shows the different ways a student can critique and write about an article

- Next: Background Information >>

- Last Updated: Jun 27, 2024 8:26 AM

- URL: https://libguides.pittcc.edu/critical_analysis

- Essay Topic Generator

- Summary Generator

- Thesis Maker Academic

- Sentence Rephraser

- Read My Paper

- Hypothesis Generator

- Cover Page Generator

- Text Compactor

- Essay Scrambler

- Essay Plagiarism Checker

- Hook Generator

- AI Writing Checker

- Notes Maker

- Overnight Essay Writing

- Topic Ideas

- Writing Tips

- Essay Writing (by Genre)

- Essay Writing (by Topic)

How to Analyze a Research Article: Guide & Analysis Examples

Analyzing a scientific paper is a complicated task that requires knowledge and systematic preparation. This process favors patience over haste and offers a deep and nuanced exploration of the presented research. Fully understanding the peculiarities of content analysis may seem complicated, especially when it comes to evaluating the results.

Our team has developed a thorough guide to make your writing process more comfortable and focused. We offer helpful tips and examples to help you create a paper worthy of admiration from college professors. This guide has everything for a stellar and in-depth argument analysis.

🤔 What Is a Research Article Analysis?

🎯 analysis of a paper: main goals.

- 📑 How to Analyze a Research Article

📝 Research Analysis Template: Essay Outline

- ✨ 5 Tips for Writing an Analysis

- ✒️ 3 Research Paper Analysis Examples

🔗 References

A research genre analysis is a genre of academic writing that lets students assess issues and arguments presented in research articles. They review the text’s content and determine its validity through critical thinking . It involves a great deal of topic analysis. After studying the source, they provide an assessment of the claims with evidence that support or disprove them. It’s their job to establish which of the statements are flawed and which are valid. Students also summarize the article and explain its relevance to the field of study.

| A good research article analysis gives the readers a comprehensive understanding of the topic. To achieve this, provide a clear summary of the work (which you can try to do using ) and enough details to get people to understand the topic. Ensure that you have a good grasp of the subject, or you won’t be able to explain it properly. | |

| Your writing should motivate others to research the subject beyond the content of the analyzed work. Write an interesting paper and make people reflect on how the research applies to them. | |

| Aside from being educational and informative, a research article analysis encourages people to think about the content of the claims. You must evaluate how well the author presented their arguments through facts and logic. Ultimately, the reader should be persuaded to side with your assessment. |

📑 How to Analyze a Research Article – 4 Key Steps

Research paper analysis is often both educational and complicated. Taking a structured approach to this task makes it a lot easier. This section of our guide discloses the four stages that help better understand the content of a scientific paper. Follow our analysis plan to learn how to write about things like results and methodology analysis .

Research Paper Analysis: Read an Article & Take Notes

You can’t critique a research piece without reading the source material first. Skimming over the paper won’t do, as you’ll miss crucial details for your analysis. Follow these steps to ensure you get the most out of the paper while critically evaluating its contents.

- Read the paper once to have a general understanding of what it’s about. Ensure you are familiar with the topic beyond elementary knowledge. You may also read up on related literature beforehand.

- Read the second time and take notes. Read the entire research paper carefully, paying attention to the results, discussion, and conclusion sections. It’s better to take detailed notes as you read, summarizing each section in your own words.

- Outline the results of the study. Write a short rundown of what the author found during the search.

Research Paper Analysis: Comprehend & Reveal the Methodology

Once you’re done with the first step, it’s time to move on to the second stage of research paper analysis: comprehending and revealing the methodology. You can’t possibly remember everything about the article so that you can revise your notes.

- Explore key terms and concepts of an article . If you don’t fully understand them, take the time to familiarize yourself with them.

- Find the hypothesis or the research question the author decided to tackle . Check the facts, arguments, and logic behind their thinking to view the paper critically.

- Look at the validity of the arguments . Research sources used in the article and assess the credibility of the supporting evidence.

- Identify the study’s methodology . Find out how the author approached the research and what its results were. Once you establish the methodology, evaluate the quality of the information, including the methods of data gathering and analysis.

Research Paper Analysis: Assess the Results

After completing the second part of the analysis, it’s time to assess the research results. Establish if the findings support the paper’s hypothesis and their statistical relevance. Address any limitations of the study . For example, a writing on psychology that uses a small group of participants that cannot be considered representative of a larger population. It may be true that the researcher did this intentionally to skew their findings. However, it’s best to be balanced in your article critique and talk about the strong sides of the paper as well. Look at similar studies and see if they came to the same conclusions.

Research Paper Analysis: Draw Conclusions

After you’ve completed the previous steps, you’re ready to make conclusions about the research paper as a whole. Don’t forget to include the following information when working on this part of the analysis:

- Determine the theoretical and practical meaning of the results. For example, if the paper found a particular treatment effective, emphasize that it should be used more often.

- Consider the applications of the research results. Try to find out how they can be applied to the broader field and what ethical implications they may lead to.

- Show how they relate to the big picture. Finally, your analysis should show how the article expands the knowledge of the subject and what it means to further studies.

Writing a research paper analysis can be demanding. These papers have several characteristics that set them apart from other types of academic writing. We’ve created this simple template to explain the content each part of your assessment should have.

| Introduction | This segment introduces both the article and your critical evaluation of it. You should name the assessed work, its author or authors, and publication date here. Explain the main ideas of the paper and state its thesis. Develop your statement and briefly explain your thoughts about the piece. Keep this section short and informative. |

| Summary | Give a rundown of the main ideas from the research article. It should answer five questions: what, why, who, when, and how. Additionally, it would help if you talked about the paper’s structure, point of view, and style. Ensure that you properly identify the research methods used in the study. Also, be sure to use topic sentences to navigate your body paragraphs, just like you would in a regular essay. |

| Analysis | Describe your attitude toward the assessed paper in this segment of your work. Write down what you liked about it and what you didn’t. with specific examples from the piece. Finally, debate whether the author was successful in their research. |

| Conclusion | The final part of your work is where you restate your paper’s thesis using different wording. Summarize presented ideas and the most critical points. Feel free to praise if the research based on facts and logic, or criticize if there is insufficient evidence and argumentation. Don’t let bias get in the way of your evaluation. |

✨ 5 Tips for Writing an Analysis of Paper

Mastering the art of writing a research paper analysis takes time and practice. We’ve decided to provide five great tips that will make this process easier and more enjoyable:

- Take the time to establish the right angle for your analysis. If you can choose its direction, study the paper first and choose the best subject for your work. You can develop several ideas and select the right one later.

- Connect all evidence to your argument. When conducting the analysis, find facts and data supporting your point of view. Explain the connection of each piece of evidence to your statement and showcase what makes it particularly significant.

- Stay balanced. A good analysis covers all facts and looks at them objectively. When confronted with data that clashes with your stance, check it and use evidence to bolster the credibility of your arguments.

- Work on an outline . Good analysis is often grounded in well-structured outline. Write down ideas and topic sentences that connect to various parts of the research sample and its general idea.

- Evaluate all evidence. All evidence has a place in your analysis. Use all of it, even if you come across contradictory facts. Include information that doesn’t fully support the main idea of your analysis and build compelling counterarguments.

️ ✒️ 3 Great Research Paper Analysis Examples

Seeing an example of a finished article can point you in the right direction. Our team has collected seven excellent essays to inspire your subsequent work and show how to approach its structure correctly.

- Analysis of The Five Dysfunctions of a Team Article . This paper concerns the pitfalls of team building in a business environment. In particular, how to overcome this environment’s five most common dysfunctions.

- When Altruism Isn’t Moral by Sally Satel : Article Analysis. The author demonstrates altruistic behavior is not always sufficient to explain human interaction. It discusses what drives people to help others for free or for money.

- Article Analysis Perceptions of ADHD Among Diagnosed Children and Their Parents. In this work, the author evaluates the findings on the perception of ADHD-diagnosed children in developed countries.

Research Article Analysis Topics

Now that you understand how to write a research paper analysis, it’s time to find the right topic for your paper. Below, you’ll find fifteen exciting ideas to inspire your analytical pursuits.

- Review a research paper on the effects of carbon emissions.

- Explore a recent research article on the use of opioids in American healthcare.

- Assess a research paper on the applications of the Large Hadron Collider.

- Discuss quantitative research about mental health rates in developed countries.

- Examine a scientific article about the problems of space exploration .

- Investigate a recent research paper about the rise of surveillance technology.

- Analyze a qualitative research paper on the effectiveness of biofuels as an alternative energy source.

- Study quantitative methods of research on the housing market in Canada.

- Scrutinize a research article about the use of pesticides in food production.

- Evaluate a paper on the efficiency of anti-climate change measures.

- Assess a recent study on the dangers of sugar consumption.

- Survey the latest research on fast food advertising tactics.

- Consider a paper on the most recent developments in string theory .

- Address a recent research article about artificial intelligence.

- Cover research about the benefits of using nuclear power.

We did our best to cover all crucial points of research article analysis and prepare you for this kind of academic work. When you have the time, share our guide with fellow students who can benefit from the content of our work!

- Analyzing Scholarly Articles. – University Writing Center

- How to Write an Analysis (With Examples and Tips). – Indeed

- Complete Guide on Article Analysis (with 1 Analysis Example). – Nerdify, Medium

- How to Read and Understand a Scientific Paper: A Guide for Non-scientists. – Jennifer Raff, LSE

- How to Review a Journal Article. – The Board of Trustees of the University of Illinois

- Critique/Review of Research Articles. – University of Calgary

- How to Summarize a Research Article. – University of Connecticut

- A Guide for Critique of Research Articles – California State Universite, Long Beach

We use cookies to give you the best experience possible. By continuing we’ll assume you’re on board with our cookie policy

- A Research Guide

- Writing Guide

- Article Writing

How to Analyze an Article

- What is an article analysis

- Outline and structure

- Step-by-step writing guide

- Article analysis format

- Analysis examples

- Article analysis template

What Is an Article Analysis?

- Summarize the main points in the piece – when you get to do an article analysis, you have to analyze the main points so that the reader can understand what the article is all about in general. The summary will be an overview of the story outline, but it is not the main analysis. It just acts to guide the reader to understand what the article is all about in brief.

- Proceed to the main argument and analyze the evidence offered by the writer in the article – this is where analysis begins because you must critique the article by analyzing the evidence given by the piece’s author. You should also point out the flaws in the work and support where it needs to be; it should not necessarily be a positive critique. You are free to pinpoint even the negative part of the story. In other words, you should not rely on one side but be truthful about what you are addressing to the satisfaction of anyone who would read your essay.

- Analyze the piece’s significance – most readers would want to see why you need to make article analysis. It is your role as a writer to emphasize the importance of the article so that the reader can be content with your writing. When your audience gets interested in your work, you will have achieved your aim because the main aim of writing is to convince the reader. The more persuasive you are, the more your article stands out. Focus on motivating your audience, and you will have scored.

Outline and Structure of an Article Analysis

What do you need to write an article analysis, how to write an analysis of an article, step 1: analyze your audience, step 2: read the article.

- The evidence : identify the evidence the writer used in the article to support their claim. While looking into the evidence, you should gauge whether the writer brings out factual evidence or it is personal judgments.

- The argument’s validity: a writer might use many pieces of evidence to support their claims, but you need to identify the sources they use and determine whether they are credible. Credible sources are like scholarly articles and books, and some are not worth relying on for research.

- How convictive are the arguments? You should be able to judge the writer’s persuasion of the audience. An article is usually informative and therefore has to be persuasive to the readers to be considered worthy. If it does not achieve this, you should be able to critique that and illustrate the same.

Step 3: Make the plan

Step 4: write a critical analysis of an article, step 5: edit your essay, article analysis format, article analysis example, what didn’t you know about the article analysis template.

- Read through the piece quickly to get an overview.

- Look for confronting words in the article and note them down.

- Read the piece for the second time while summarizing major points in the literature piece.

- Reflect on the paper’s thesis to affirm and adhere to it in your writing.

- Note the arguments and the evidence used.

- Evaluate the article and focus on your audience.

- Give your opinion and support it to the satisfaction of your audience.

Receive paper in 3 Hours!

- Choose the number of pages.

- Select your deadline.

- Complete your order.

Number of Pages

550 words (double spaced)

Deadline: 10 days left

By clicking "Log In", you agree to our terms of service and privacy policy . We'll occasionally send you account related and promo emails.

Sign Up for your FREE account

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- HCA Healthc J Med

- v.1(2); 2020

- PMC10324782

Introduction to Research Statistical Analysis: An Overview of the Basics

Christian vandever.

1 HCA Healthcare Graduate Medical Education

Description

This article covers many statistical ideas essential to research statistical analysis. Sample size is explained through the concepts of statistical significance level and power. Variable types and definitions are included to clarify necessities for how the analysis will be interpreted. Categorical and quantitative variable types are defined, as well as response and predictor variables. Statistical tests described include t-tests, ANOVA and chi-square tests. Multiple regression is also explored for both logistic and linear regression. Finally, the most common statistics produced by these methods are explored.

Introduction

Statistical analysis is necessary for any research project seeking to make quantitative conclusions. The following is a primer for research-based statistical analysis. It is intended to be a high-level overview of appropriate statistical testing, while not diving too deep into any specific methodology. Some of the information is more applicable to retrospective projects, where analysis is performed on data that has already been collected, but most of it will be suitable to any type of research. This primer will help the reader understand research results in coordination with a statistician, not to perform the actual analysis. Analysis is commonly performed using statistical programming software such as R, SAS or SPSS. These allow for analysis to be replicated while minimizing the risk for an error. Resources are listed later for those working on analysis without a statistician.

After coming up with a hypothesis for a study, including any variables to be used, one of the first steps is to think about the patient population to apply the question. Results are only relevant to the population that the underlying data represents. Since it is impractical to include everyone with a certain condition, a subset of the population of interest should be taken. This subset should be large enough to have power, which means there is enough data to deliver significant results and accurately reflect the study’s population.

The first statistics of interest are related to significance level and power, alpha and beta. Alpha (α) is the significance level and probability of a type I error, the rejection of the null hypothesis when it is true. The null hypothesis is generally that there is no difference between the groups compared. A type I error is also known as a false positive. An example would be an analysis that finds one medication statistically better than another, when in reality there is no difference in efficacy between the two. Beta (β) is the probability of a type II error, the failure to reject the null hypothesis when it is actually false. A type II error is also known as a false negative. This occurs when the analysis finds there is no difference in two medications when in reality one works better than the other. Power is defined as 1-β and should be calculated prior to running any sort of statistical testing. Ideally, alpha should be as small as possible while power should be as large as possible. Power generally increases with a larger sample size, but so does cost and the effect of any bias in the study design. Additionally, as the sample size gets bigger, the chance for a statistically significant result goes up even though these results can be small differences that do not matter practically. Power calculators include the magnitude of the effect in order to combat the potential for exaggeration and only give significant results that have an actual impact. The calculators take inputs like the mean, effect size and desired power, and output the required minimum sample size for analysis. Effect size is calculated using statistical information on the variables of interest. If that information is not available, most tests have commonly used values for small, medium or large effect sizes.

When the desired patient population is decided, the next step is to define the variables previously chosen to be included. Variables come in different types that determine which statistical methods are appropriate and useful. One way variables can be split is into categorical and quantitative variables. ( Table 1 ) Categorical variables place patients into groups, such as gender, race and smoking status. Quantitative variables measure or count some quantity of interest. Common quantitative variables in research include age and weight. An important note is that there can often be a choice for whether to treat a variable as quantitative or categorical. For example, in a study looking at body mass index (BMI), BMI could be defined as a quantitative variable or as a categorical variable, with each patient’s BMI listed as a category (underweight, normal, overweight, and obese) rather than the discrete value. The decision whether a variable is quantitative or categorical will affect what conclusions can be made when interpreting results from statistical tests. Keep in mind that since quantitative variables are treated on a continuous scale it would be inappropriate to transform a variable like which medication was given into a quantitative variable with values 1, 2 and 3.

Categorical vs. Quantitative Variables

| Categorical Variables | Quantitative Variables |

|---|---|

| Categorize patients into discrete groups | Continuous values that measure a variable |

| Patient categories are mutually exclusive | For time based studies, there would be a new variable for each measurement at each time |

| Examples: race, smoking status, demographic group | Examples: age, weight, heart rate, white blood cell count |

Both of these types of variables can also be split into response and predictor variables. ( Table 2 ) Predictor variables are explanatory, or independent, variables that help explain changes in a response variable. Conversely, response variables are outcome, or dependent, variables whose changes can be partially explained by the predictor variables.

Response vs. Predictor Variables

| Response Variables | Predictor Variables |

|---|---|

| Outcome variables | Explanatory variables |

| Should be the result of the predictor variables | Should help explain changes in the response variables |

| One variable per statistical test | Can be multiple variables that may have an impact on the response variable |

| Can be categorical or quantitative | Can be categorical or quantitative |

Choosing the correct statistical test depends on the types of variables defined and the question being answered. The appropriate test is determined by the variables being compared. Some common statistical tests include t-tests, ANOVA and chi-square tests.

T-tests compare whether there are differences in a quantitative variable between two values of a categorical variable. For example, a t-test could be useful to compare the length of stay for knee replacement surgery patients between those that took apixaban and those that took rivaroxaban. A t-test could examine whether there is a statistically significant difference in the length of stay between the two groups. The t-test will output a p-value, a number between zero and one, which represents the probability that the two groups could be as different as they are in the data, if they were actually the same. A value closer to zero suggests that the difference, in this case for length of stay, is more statistically significant than a number closer to one. Prior to collecting the data, set a significance level, the previously defined alpha. Alpha is typically set at 0.05, but is commonly reduced in order to limit the chance of a type I error, or false positive. Going back to the example above, if alpha is set at 0.05 and the analysis gives a p-value of 0.039, then a statistically significant difference in length of stay is observed between apixaban and rivaroxaban patients. If the analysis gives a p-value of 0.91, then there was no statistical evidence of a difference in length of stay between the two medications. Other statistical summaries or methods examine how big of a difference that might be. These other summaries are known as post-hoc analysis since they are performed after the original test to provide additional context to the results.

Analysis of variance, or ANOVA, tests can observe mean differences in a quantitative variable between values of a categorical variable, typically with three or more values to distinguish from a t-test. ANOVA could add patients given dabigatran to the previous population and evaluate whether the length of stay was significantly different across the three medications. If the p-value is lower than the designated significance level then the hypothesis that length of stay was the same across the three medications is rejected. Summaries and post-hoc tests also could be performed to look at the differences between length of stay and which individual medications may have observed statistically significant differences in length of stay from the other medications. A chi-square test examines the association between two categorical variables. An example would be to consider whether the rate of having a post-operative bleed is the same across patients provided with apixaban, rivaroxaban and dabigatran. A chi-square test can compute a p-value determining whether the bleeding rates were significantly different or not. Post-hoc tests could then give the bleeding rate for each medication, as well as a breakdown as to which specific medications may have a significantly different bleeding rate from each other.

A slightly more advanced way of examining a question can come through multiple regression. Regression allows more predictor variables to be analyzed and can act as a control when looking at associations between variables. Common control variables are age, sex and any comorbidities likely to affect the outcome variable that are not closely related to the other explanatory variables. Control variables can be especially important in reducing the effect of bias in a retrospective population. Since retrospective data was not built with the research question in mind, it is important to eliminate threats to the validity of the analysis. Testing that controls for confounding variables, such as regression, is often more valuable with retrospective data because it can ease these concerns. The two main types of regression are linear and logistic. Linear regression is used to predict differences in a quantitative, continuous response variable, such as length of stay. Logistic regression predicts differences in a dichotomous, categorical response variable, such as 90-day readmission. So whether the outcome variable is categorical or quantitative, regression can be appropriate. An example for each of these types could be found in two similar cases. For both examples define the predictor variables as age, gender and anticoagulant usage. In the first, use the predictor variables in a linear regression to evaluate their individual effects on length of stay, a quantitative variable. For the second, use the same predictor variables in a logistic regression to evaluate their individual effects on whether the patient had a 90-day readmission, a dichotomous categorical variable. Analysis can compute a p-value for each included predictor variable to determine whether they are significantly associated. The statistical tests in this article generate an associated test statistic which determines the probability the results could be acquired given that there is no association between the compared variables. These results often come with coefficients which can give the degree of the association and the degree to which one variable changes with another. Most tests, including all listed in this article, also have confidence intervals, which give a range for the correlation with a specified level of confidence. Even if these tests do not give statistically significant results, the results are still important. Not reporting statistically insignificant findings creates a bias in research. Ideas can be repeated enough times that eventually statistically significant results are reached, even though there is no true significance. In some cases with very large sample sizes, p-values will almost always be significant. In this case the effect size is critical as even the smallest, meaningless differences can be found to be statistically significant.

These variables and tests are just some things to keep in mind before, during and after the analysis process in order to make sure that the statistical reports are supporting the questions being answered. The patient population, types of variables and statistical tests are all important things to consider in the process of statistical analysis. Any results are only as useful as the process used to obtain them. This primer can be used as a reference to help ensure appropriate statistical analysis.

| Alpha (α) | the significance level and probability of a type I error, the probability of a false positive |

| Analysis of variance/ANOVA | test observing mean differences in a quantitative variable between values of a categorical variable, typically with three or more values to distinguish from a t-test |

| Beta (β) | the probability of a type II error, the probability of a false negative |

| Categorical variable | place patients into groups, such as gender, race or smoking status |

| Chi-square test | examines association between two categorical variables |

| Confidence interval | a range for the correlation with a specified level of confidence, 95% for example |

| Control variables | variables likely to affect the outcome variable that are not closely related to the other explanatory variables |

| Hypothesis | the idea being tested by statistical analysis |

| Linear regression | regression used to predict differences in a quantitative, continuous response variable, such as length of stay |

| Logistic regression | regression used to predict differences in a dichotomous, categorical response variable, such as 90-day readmission |

| Multiple regression | regression utilizing more than one predictor variable |

| Null hypothesis | the hypothesis that there are no significant differences for the variable(s) being tested |

| Patient population | the population the data is collected to represent |

| Post-hoc analysis | analysis performed after the original test to provide additional context to the results |

| Power | 1-beta, the probability of avoiding a type II error, avoiding a false negative |

| Predictor variable | explanatory, or independent, variables that help explain changes in a response variable |

| p-value | a value between zero and one, which represents the probability that the null hypothesis is true, usually compared against a significance level to judge statistical significance |

| Quantitative variable | variable measuring or counting some quantity of interest |

| Response variable | outcome, or dependent, variables whose changes can be partially explained by the predictor variables |

| Retrospective study | a study using previously existing data that was not originally collected for the purposes of the study |

| Sample size | the number of patients or observations used for the study |

| Significance level | alpha, the probability of a type I error, usually compared to a p-value to determine statistical significance |

| Statistical analysis | analysis of data using statistical testing to examine a research hypothesis |

| Statistical testing | testing used to examine the validity of a hypothesis using statistical calculations |

| Statistical significance | determine whether to reject the null hypothesis, whether the p-value is below the threshold of a predetermined significance level |

| T-test | test comparing whether there are differences in a quantitative variable between two values of a categorical variable |

Funding Statement

This research was supported (in whole or in part) by HCA Healthcare and/or an HCA Healthcare affiliated entity.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares he has no conflicts of interest.

Christian Vandever is an employee of HCA Healthcare Graduate Medical Education, an organization affiliated with the journal’s publisher.

This research was supported (in whole or in part) by HCA Healthcare and/or an HCA Healthcare affiliated entity. The views expressed in this publication represent those of the author(s) and do not necessarily represent the official views of HCA Healthcare or any of its affiliated entities.

How to Write an Article Analysis

What Are the Five Parts of an Argumentative Essay?

As you write an article analysis, focus on writing a summary of the main points followed by an analytical critique of the author’s purpose.

Knowing how to write an article analysis paper involves formatting, critical thinking of the literature, a purpose of the article and evaluation of the author’s point of view. In an article analysis critique, you integrate your perspective of the author about a specific topic into a mix of reasoning and arguments. So, you develop an argumentative approach to the point of view of the author. However, a careful distinction occurs between summary and analysis.

When presenting your findings of the article analysis, you might want to summarize the main points, which allows you to formulate a thesis statement. Then, inform the readers about the analytical aspects the author presents in his arguments. Most likely, developing ideas on how to write an article analysis entails a meticulous approach to the critical thinking of the author.

Writing Steps for an Article Analysis

As with any formal paper, you want to begin by quickly reading the article to get the main points. Once you generate a general idea of the point of view of the author, start analyzing the main ideas of each paragraph. An ideal way to take notes based on the reading is to jot them down in the margin of the article. If that's not possible, include notes on your computer or a separate piece of paper. Interact with the text you're reading.

Becoming an active reader helps you decide the relevant information the author intends to communicate. At this point, you might want to include a summary of the main ideas. After you finish writing down the main points, read them to yourself and decide on a concise thesis statement. To do so, begin with the author’s name followed by the title of the article. Next, complete the sentence with your analytical perspective.

Ideally, you want to use outlines, notes and concept mapping to draft your copy. As you progress through the body of the critical part of the paper, include relevant information such as literature references and the author’s purpose for the article. Formal documents, such as an article analysis, also use in-text citation and proofreading. Any academic paper includes a grammar, spelling and mechanics proofreading. Make sure you double-check your paper before submission.

When you write the summary of the article, focus on the purpose of the paper and develop ideas that inform the reader in an unbiased manner. One of the most crucial parts of an analysis essay is the citation of the author and the title of the article. First, introduce the author by first and last name followed by the title of the article. Add variety to your sentence structure by using different formats. For example, you can use “Title,” author’s name, then a brief explanation of the purpose of the piece. Also, many sentences might begin with the author, “Title,” then followed by a description of the main points. By implementing active, explicit verbs into your sentences, you'll show a clear understanding of the material.

Much like any formal paper, consider the most substantial points as your main ideas followed by evidence and facts from the author’s persuasive text. Remember to use transition words to guide your readers in the writing. Those transition phrases or words encourage readers to understand your perspective of the author’s purpose in the article. More importantly, as you write the body of the analysis essay, use the author’s name and article title at the beginning of a paragraph.

When you write your evidence-based arguments, keep the author’s last name throughout the paper. Besides writing your critique of the author’s purpose, remember the audience. The readers relate to your perspective based on what you write. So, use facts and evidence when making inferences about the author’s point of view.

Description of an Article Analysis Essay

When you analyze an article based on the argumentative evidence, generate ideas that support or not the author’s point of view. Although the author’s purpose to communicate the intentions of the article may be clear, you need to evaluate the reasons for writing the piece. Since the basis of your analysis consists of argumentative evidence, elaborate a concise and clear thesis. However, don't rely on the thesis to stay the same as you research the article.

At many times, you'll find that you'll change your argument when you see new facts. In this way, you might want to use text, reader, author, context and exigence approaches. You don't need elaborate ideas. Just use the author’s text so that the reader understands the point of views. However, evaluate the strong tone of the author and the validity of the claims in the article. So, use the context of the article.

Then, ask yourself if the author explains the purpose of his or her persuasive reasons. As you discern the facts and evidence of the article, analyze the point of views carefully. Look for assumptions without basis and biased ideas that aren't valid. An analysis example paragraph easily includes your perspective of the author’s purpose and whether you agree or not. Don't be surprised if your critique changes as you research other authors about the article.

Consequently, your response might end up agreeing, disagreeing or being somewhat in between despite your efforts of finding supporting evidence. Regardless of the consequences of your research of the literature and the perspective of the author’s point of view, maintain a definite purpose in writing. Don't fluctuate from agreement and disagreement. Focusing your analysis on presenting the points of view of the author so readers understand it and disseminating that critique is the basis of your paper.