- Architecture and Design

- Asian and Pacific Studies

- Business and Economics

- Classical and Ancient Near Eastern Studies

- Computer Sciences

- Cultural Studies

- Engineering

- General Interest

- Geosciences

- Industrial Chemistry

- Islamic and Middle Eastern Studies

- Jewish Studies

- Library and Information Science, Book Studies

- Life Sciences

- Linguistics and Semiotics

- Literary Studies

- Materials Sciences

- Mathematics

- Social Sciences

- Sports and Recreation

- Theology and Religion

- Publish your article

- The role of authors

- Promoting your article

- Abstracting & indexing

- Publishing Ethics

- Why publish with De Gruyter

- How to publish with De Gruyter

- Our book series

- Our subject areas

- Your digital product at De Gruyter

- Contribute to our reference works

- Product information

- Tools & resources

- Product Information

- Promotional Materials

- Orders and Inquiries

- FAQ for Library Suppliers and Book Sellers

- Repository Policy

- Free access policy

- Open Access agreements

- Database portals

- For Authors

- Customer service

- People + Culture

- Journal Management

- How to join us

- Working at De Gruyter

- Mission & Vision

- De Gruyter Foundation

- De Gruyter Ebound

- Our Responsibility

- Partner publishers

Your purchase has been completed. Your documents are now available to view.

We Are What We Eat

Ethnic food and the making of americans.

- Donna R. Gabaccia

- X / Twitter

Please login or register with De Gruyter to order this product.

- Language: English

- Publisher: Harvard University Press

- Copyright year: 2000

- Audience: Professional and scholarly;

- Main content: 288

- Published: July 1, 2009

- ISBN: 9780674037441

(Stanford users can avoid this Captcha by logging in.)

- Send to text email RefWorks EndNote printer

We are what we eat : ethnic food and the making of Americans

Available online, at the library.

Green Library

More options.

- Find it at other libraries via WorldCat

- Contributors

Description

Creators/contributors, contents/summary.

- Introduction - what do we eat?

- colonial Creoles

- immigration, isolation and industry

- ethnic entrepreneurs

- crossing the boundaries of taste

- food fights and American values

- the big business of eating

- of cookbooks and culinary roots

- nouvelle Creole

- conclusion - who are we?

- (source: Nielsen Book Data)

Bibliographic information

Browse related items.

- Stanford Home

- Maps & Directions

- Search Stanford

- Emergency Info

- Terms of Use

- Non-Discrimination

- Accessibility

© Stanford University , Stanford , California 94305 .

Privacy and cookies policy

We use cookies on our website to help us understand how you use the site and to make improvements. These may be used to track your visit to our website or to enable us to personalise your browsing experience, and they may be shared with Google Analytics so that your data can be processed. Privacy and cookies policy

What we eat matters: Health and environmental impacts of diets worldwide

Dr Marco Springmann (Lead author) , Dr Dariush Mozaffarian , Dr Cynthia Rosenzweig , Dr Renata Micha

- The previous decade has seen little progress in improving diets, and a quarter of all deaths among adults are attributable to poor diets – those low in fruits, vegetables, nuts/seeds and whole grains, and high in red and processed meat and sugary drinks.

- Food production currently generates more than a third of all greenhouse gas emissions globally, and uses substantial and rising amounts of environmental resources, including land, water and nitrogen- and phosphorus-containing fertilisers.

- Current dietary patterns globally and in most regions are neither healthy nor sustainable. No region is on track to meet the Sustainable Development Goals aimed at limiting health and environmental burdens related to diets and the food system.

Introduction

Our diets affect both our own health and the health of the planet. [1] [2] Imbalanced diets low in fruits, vegetables, legumes, nuts/seeds and whole grains, and high in red and processed meat are responsible for one of the greatest health burdens globally and in most regions. [3] [4] At the same time, our diets and the food system underpinning them are major drivers of environmental pollution and resource demand, which is contributing to the crossing of key planetary boundaries that attempt to define a safe operating space for humanity on a stable Earth system. [5] Preserving the integrity of our environment and the health of populations will require substantial changes in the foods we produce and eat. [6] [7]

This chapter discusses the current state of diets worldwide and presents new estimates of the associated health and environmental impacts both globally and nationally. First, we survey how the demand for health and environmentally important foods has changed between 2010 and 2018 (the last year for which data is available) and compare the current dietary trends to food-group targets for healthy and sustainable diets. Second, based on epidemiological relationships that connect food intake with risks for diet-related diseases, we estimate the health implications of current diets. Third, based on the environmental footprints of foods, we estimate the environmental impacts of the food supply. The forthcoming methodology for this chapter contains a detailed description of the analytical methods used. We start by identifying key foods important for both human health and the environment.

Foods of concern

A healthy diet consists of plenty of fruits, vegetables, legumes, nuts/seeds, whole grains and oils high in unsaturated fats, and little to no red and processed meat, sugar-sweetened beverages, refined grains and oils high in saturated fats. [8] [9] [10] [11] Nutritional epidemiology has identified many of those aspects as key risk factors for or against leading causes of overall illness and death, including coronary heart disease, stroke, type-2 diabetes and several cancers. Between 20% and 25% of all deaths in adults have been associated with imbalanced diets. [12] [13] [14]

Advances in nutritional science in the last two decades now provide a substantial body of evidence to identify key dietary priorities for action. The evidence linking diets to intermediate risk factors (e.g. raised blood pressure) and final health (disease) outcomes (e.g. heart disease) comes from various lines of evidence. These include studies of biological processes, clinical trials of risk factors, long-term observational studies of health outcomes, and clinical trials of health outcomes. The different study designs have complementary strengths and weaknesses, and their similar conclusions from different approaches provide increasingly robust evidence. [15] [16] [17] [18] [19] [20]

For our analysis, we followed several steps to ensure that our selection or diet factors reflects the current evidence on healthy eating. First, we focused on evidence from meta-analyses that have pooled all available studies linking diets to health outcomes, to minimise bias from any one study. Second, we only used diet–disease associations whose strength of evidence in meta-analyses was graded as moderate or high, or as probable and convincing. Third, we did not include diet–disease associations, e.g. for dairy products [21] [22] and fish, [23] [24] [25] [26] which became statistically non-significant when adjusted for potential confounding factors, such as co-consumption with other foods. Fourth, we focused on foods and not nutrients, to reduce the risk of double-counting as foods often include several nutrients. Further details are provided in the forthcoming methodology (see the section called Data for comparative risk assessment). We focused on foods with impacts on coronary heart disease, stroke, diabetes, cancers and respiratory disease.

When it comes to the environmental impacts of foods, it is generally recognised that animal-based foods have greater environmental impacts than plant-based foods. [27] [28] [29] For example, for greenhouse gas emissions, beef and lamb have about ten times the emissions per serving as pork, poultry and dairy products, and those have about ten times the emissions of plant-based foods, including grains, fruits and vegetables, and legumes. Similarly for water, the average fresh-water footprint per tonne of animal-based product is greater than that of plant-based products, with the exception of milk, which has a relatively low water footprint, and nuts, which have a relatively high water footprint when measured on a per-tonne basis, but not on a per-calorie or per-protein basis. [30]

Much of the evidence linking environmental impacts to foods comes from life-cycle analyses that record the various impacts across all stages of the food chain, including production, transport, processing and consumption. The strength of life-cycle analysis is that both direct and indirect impacts are accounted for, something that explains the differentiated impacts of foods. Animal-based foods tend to have greater footprints of greenhouse gas emissions than plant-based foods because, in addition to direct emissions from manure and, for ruminant animals, their digestion, animals also generate indirect emissions from their feed whose production generates emissions and requires large amounts of environmental resources, including land, water and fertilisers.

For our analysis, we used the most recent and comprehensive set of life-cycle assessments to estimate the environmental impacts of diets (see the section called Environmental analysis in the forthcoming methodology). We included in our assessment the impacts of foods on greenhouse gas emissions, cropland use, fresh-water use and nitrogen and phosphorus application related to fertilisers. Dietary changes towards more plant-based diets have been identified as the most efficient way of reducing the greenhouse gas emissions of the food system. [31] Several technological and management options exist for reducing other environmental impacts. However, when it comes to greenhouse gas emissions, those are relatively ineffective because most emissions are associated with the characteristics of animals, such as feed requirements and digestion-related gases, that cannot be altered substantially. This makes dietary changes towards less-impact foods one of the most important climate-change measures. [32] Therefore, we focus here on the greenhouse gas emissions associated with food demand, but also highlight other impacts.

The global and regional state of dietary intakes

The last decade, based on data for 2010 and 2018, has seen little progress in improving diets (Figure 2.1). Based on analyses of the latest data on average per-person dietary intakes from the Global Dietary Database, [33] intakes of whole grains, and of fruit and vegetables, both critical components of healthy diets, have increased by a mere 2% globally, fish intake remained unchanged, while legume consumption has decreased on average (−4%) and the consumption of sugary drinks has increased (+4%). Among the health-promoting foods, only nut/seed intake showed more substantial increases (+17%), albeit from a very low baseline. Global dairy intake (measured in milk equivalent in grams per day, g/d) has decreased (−7%), but the intake of other foods associated with high environmental and health impacts, in particular red meat and processed meat, has increased (+2–3%). In addition, overeating and, associated with that, the proportion of overweight and obesity, have increased almost five times more (+0.70%) than levels of underweight have decreased (−0.15%). [34]

Both positive and negative dietary changes were often confined to high- and upper-middle-income countries, with least progress in low-income countries (Figure 2.1). For example, the average fruit and vegetable intake per person increased in Latin America and the Caribbean (+8%), Europe (+5%), Asia (+4%); it stayed unchanged in Northern America; and it decreased in Africa (−4%) and Oceania (−13%). Likewise, red and processed meat intake increased in Oceania (+59%), Latin America and the Caribbean (+7%), Asia (+6%) and Europe (+4%); it changed little in Northern America (+1%); and it decreased in Africa (−10%). Overweight and obesity increased in every region, with up to 3% in Asia, while underweight decreased least in Africa (−0.2%).

Figure 2.1 The last decade has seen little progress in improving diets

Food intake by food group, year and region (grams per person per day), 2010 and 2018

Source: Authors, based on new analysis based on the Global Dietary Database. [35]

Notes: Dairy is reported in milk equivalents. The selection of food groups is based on their health and environmental impacts. Our analysis includes diet–disease association for low intake of fruits, vegetables, legumes, nuts/seeds and whole grains; and for high intake of red meat, processed meat and sugary drinks. All food groups have environmental impacts, with particularly high impacts for animal source foods.

- Download data: Figure 2.1

Current dietary patterns are neither healthy, nor sustainable. Compared to recommendations for healthy and sustainable diets developed by the EAT-Lancet Commission on Healthy Diets from Sustainable Food Systems (Box 2.1), the intake of health-promoting foods in 2018 remains too low and that of foods with high health and environmental impacts remains too high (Figure 2.2). Global vegetable intake is 40% below the recommended three servings per day, fruit intake 60% below the recommended two servings per day and legume and nuts intake 68–74% below the one to two recommended servings. Red and processed meat intake is almost five times above recommendations. Only milk and fish intakes are within recommended ranges. In addition, about half of the global population (48%) eats too many or too few calories and exhibits imbalanced weight levels, including overweight (26%), obesity (13%) and underweight (9%).

Box 2.1: Recommendations for healthy diets from sustainable food systems

Marco Springmann

The EAT-Lancet Commission on Healthy Diets from Sustainable Food Systems was a scientific commission on how to achieve a sustainable food system that can deliver healthy diets for a growing population. Convened between 2017 and 2019, it consisted of 19 commissioners and 18 co-authors from 16 countries and various fields, including human health, agriculture, political science and environmental sustainability. Its report was published in the medical science journal The Lancet in 2019. [36]

The Commission’s work included the development of: new recommendations for healthy diets based on a comprehensive review of the literature on healthy eating; science-based targets for sustainable food production that included the definition of planetary boundaries of the food system; analyses of the health, nutritional and environmental impacts of dietary and food-system changes that would be needed to stay within planetary boundaries; and strategies for a ‘great food transformation’ towards healthy diets from sustainable food systems by 2050.

In this chapter, we use the EAT-Lancet Commission’s dietary recommendations and the science-based targets for sustainable food production to compare current dietary patterns with the current scientific understanding of healthy eating and sustainable diets. The EAT-Lancet recommendations provide ranges of intake for all major food groups that allow for the adoption of various dietary patterns and culinary traditions, and their impacts on health and the environment have been widely assessed, both within the Commission and independently.

Dietary patterns in line with the recommendations have been found to be associated with improvements in diet-related disease mortality, nutritional adequacy and environmental sustainability, [37] [38] [39] [40] exceeding existing national food-based dietary guidelines and those of the World Health Organization on each dimension. [41] Although many healthy and dietary patterns are currently more affordable than typical Western diets in high- and middle-income countries, their adoption can be challenging in low-income contexts where diets are dominated by low-cost roots and grains and lack the diverse set of more expensive healthy foods. [42] [43] This stresses the need for food-system strategies that would make healthy and sustainable diets affordable for all, including full costing approaches, income support and socioeconomic development.

Despite variation, no region met the recommendations for healthy and sustainable diets. Lower-income countries continue to have the lowest intake levels of health-promoting foods and the highest levels of underweight, while higher-income countries have the highest intake levels of foods with high environmental and health impacts, and the highest levels of overweight and obesity (Figure 2.2). For example, fruit and vegetable consumption in 2018 was 59% below recommended intake in Africa, but also 41% and 56% below recommendations in Europe and Northern America, respectively. Red and processed meat intake was eight to nine times too high in Europe, Oceania and Latin America, but it was also double the recommended value in Africa and four times above the target in Asia.

Figure 2.2 Dietary patterns do not meet recommendations for healthy and sustainable diets

Percentage deviation by year and region from recommendations of the EAT-Lancet Commission on Healthy Diets from Sustainable Food Systems

Source: New analysis using the Global Dietary Database and recommendations of the EAT-Lancet Commission.

Notes: Includes minimum recommended intake of health-promoting foods (fruits, vegetables, legumes, nuts, whole grains), maximum recommended intake of foods with detrimental health and/or environmental impacts (red meat, processed meat, dairy, fish), and from normal weight levels (underweight, overweight, obesity). Colours indicate that intake is either in line with recommendations (ranging from green to yellow with decreasing compliance) or deviate from recommendations (ranging from yellow to red with increasing deviation).

- Download data: Figure 2.2

The health burden of diets

The current level of dietary imbalance can have serious implications for human and planetary health. For this report, we produced new estimates of the health burden of poor diets by using a global comparative assessment of dietary risks with country-level detail (see the sections called Comparative risk assessment and Data for comparative risk assessment in the forthcoming methodology). The assessment combines estimates of food intake with cause-specific mortality rates via a comprehensive set of diet–disease relationships, each accounting for physiological (age, sex) and geographic (country-level) variation. [44] In this framework, we accounted for risks for diet-related, non-communicable diseases (NCDs) associated with imbalanced diets, such as those low in fruits and vegetables, as well as for risk associated with imbalanced energy intake related to underweight, overweight and obesity. Because risks for NCDs primarily affect adults, we focused on risks to those aged 20 and above. In this chapter, we report the mean values of our estimates for ease of presentation. The low and high values of 95% confidence intervals are provided in the forthcoming dataset that will be online.

According to our estimates, today’s diets are associated with a large and increasing health burden (Figure 2.3). Overall, poor diets were responsible for more than 12 million avoidable deaths in 2018, which represents 26% of all deaths among adults. Compared to 2010, the number of avoidable deaths due to diet grew by 15%, more rapidly than the population (10%). Almost half of the avoidable deaths were from coronary heart disease (5.9 million, 47%), about a fifth each from cancers (2.8 million, 22%) and stroke (2.4 million, 19%) and around 5% each from type-2 diabetes (690,000) and respiratory diseases (760,000). Our estimate of attributable deaths is comparable to the combination of diet- and weight-related risk estimates of the Global Burden of Disease project (7.8 and 4.8 million attributable deaths, respectively).

About two-thirds of the avoidable deaths in our analysis (9.3 million, 65%) were due to risks related to dietary composition, including low intake of fruits (2.8 million, 25% of the avoidable composition-related risks), whole grains (2.3 million, 20%), vegetables (1.7 million, 14%), legumes (1.5 million, 13%), nuts and seeds (1.0 million, 9%), and high intake of red meat (980,000, 9%), processed meat (880,000, 8%) and sugar-sweetened beverages (290,000, 3%). The remaining third (5.0 million, 35%) of the avoidable deaths were due to risks related to total energy intake and body weight, including obesity (2.7 million, 54% of the avoidable weight-related deaths), overweight (1.2 million, 24%) and underweight (1.1 million, 22%).

Figure 2.3 The dietary health burden is increasing

Deaths attributable to dietary risk factors by cause of death for risks related to dietary composition and weight levels, 2010 and 2018

Source: New analysis based on estimates of food intake from the Global Dietary Database, [45] weight measurements from the NCD Risk Factor Collaboration, [46] diet-disease relationships from the epidemiological literature, [47] [48] [49] [50] [51] [52] and mortality and population estimates from the Global Burden of Disease project. [53]

Note: The combined risk is less than the sum of individual risks because individuals can be exposed to multiple risks, but mortality is ascribed to one risk and cause.

- Download data: Figure 2.3

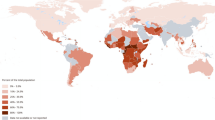

The proportion of premature death attributed to dietary risks differs markedly by region, reflecting regional differences in diets as well as the contribution of NCDs (Figure 2.4). It is highest in higher-income regions, including Northern America (31%) and Europe (31%), and lowest in lower-income regions such as Africa (17%). Among the dietary risks evaluated, the leading causes of dietary ill health were similar in each region and included low intake of fruits and vegetables (5–8% of premature mortality across regions), whole grains (2–5%), and high intake of red and processed meat (1–6%), as well as high levels of overweight and obesity (5–13%).

No region was in line with the health-related sustainable development goal (SDG) of reducing premature mortality from NCDs by a third between 2015 and 2030 (SDG 3.4). Among the regions, there was either very little progress, with a 3% reduction in Northern America in premature mortality from dietary risks, or trends towards higher premature mortality from dietary risks in the remaining regions, with particularly large increases in Africa (+22%), Latin America and the Caribbean (+8%) and Asia (+7%), followed by Oceania (+4%) and Europe (+2%).

Figure 2.4 The rise in premature death from dietary risks is not in line with global health goals

Percentage of premature death attributable to dietary risks by region, 2010 and 2018

Source: New analysis based on estimates of food intake from the Global Dietary Database, weight measurements from the NCD Risk Factor Collaboration, diet-disease relationships from the epidemiological literature, and mortality and population estimates from the Global Burden of Disease project.

- Download data: Figure 2.4

The environmental burden of diets

Our dietary habits and the current level and mix of foods we demand are also associated with substantial and increasing levels of environmental pollution and resource use (Figure 2.5). For this new analysis, we paired data on food demand for each country from the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations with a comprehensive database of environmental footprints, differentiated by country, food group and environmental impact (see the section called Environmental analysis in the forthcoming methodology). [54] The footprints take into account all food production, including inputs such as fertilisers and feed, transport and processing e.g. of oil seeds to oils and sugar crops to sugar.

According to our estimates, the global food demand, including food loss and waste, generated 17.2 billion tonnes of greenhouse gas emissions (measured in carbon dioxide equivalents, GtCO2eq) in 2018, which represents more than a third (35%) of global emissions. Methane and nitrous oxide, two greenhouse gases primarily associated with agriculture, contributed 7.5GtCO2eq. The food system also required 15.8 million square kilometres (Mkm2) of cropland and 43.9Mkm2 of pastureland, 2,500 cubic kilometres (km3) of fresh water, 108.7 million tonnes (Mt) of nitrogen and 18.6Mt phosphorus. Compared to 2010, the environmental impacts of food demand increased by up to 14%. Our estimates are in line with other available estimates.

Animal-source foods have generally higher environmental footprints per product than plant-based foods. Consequently, they were responsible for the majority of food-related greenhouse gas emissions (80% of methane and nitrous oxide emissions and 56% of all food-related greenhouse emissions) and land use (85%), with particularly large impacts from beef, lamb and dairy. Through feed demand, animal-source foods were also responsible for about a quarter each of nitrogen and phosphorus application and a tenth of fresh-water use. Among plant-based foods, grain production (including rice) required almost half (43–52%) of the food-related fresh water, nitrogen and phosphorus, not because of its high footprint, but because of the large absolute quantity of production.

Figure 2.5 Environmental impacts of the food system are increasing

Food-related environmental impacts by environmental domain and food group, 2010 and 2018

Source: New analysis based on estimates of food demand from the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations [55] and a database of country and food-group-specific environmental footprints.

Note: Values for environmental impact for 2018 are expressed as a ratio to the impacts for 2010.

- Download data: Figure 2.5

The environmental impacts of the global food system are not in line with global environmental targets (Figure 2.6) as specified by the EAT-Lancet Commission on Healthy Diets from Sustainable Food Systems (Box 2.1). In 2018, food-related greenhouse gas emissions exceeded by three-quarters (74%) the limit required by the Paris Climate Agreement (target 13 of the sustainable development goals, SDGs) to limit global warming to below 2°C. Cropland use was 60% above the value that would be in line with limiting the loss of natural habitat (Aichi Biodiversity Targets and SDG 15). Freshwater use exceeded rates of sustainable withdrawals by more than 52% (SDG 6.4). Nitrogen application was more than double (113%) and phosphorus application two-thirds (67%) above values that would limit marine pollution to acceptable levels (SDG 14.1).

No region is on track to fulfil the set of sustainable development goals related to the environmental impacts of the food system (Figure 2.6). This can best be illustrated by a global sustainability test in which the dietary pattern and food demand of a particular region or country is adopted globally (see the section called Global health and environmental targets in the forthcoming methodology). If the globalised impacts exceed the targets for sustainable food production that would be in line with the SDGs, then the dietary pattern of that particular region or country can be considered unsustainable in light of global environmental targets and disproportionate in the context of an equitable distribution of environmental resources and mitigation efforts. For example, if globally adopted, the dietary patterns of Northern America would result in a level of greenhouse gas emissions more than six times above a value in line with limiting global warming to below 2°C. The corresponding emission levels are more than five times above the target value in Oceania, four times the target value in Latin America and Europe, and 60–75% above sustainable levels in Africa and Asia.

Figure 2.6 No region is on track to meet global environmental targets related to the food system

Global sustainability test comparing global impacts with global environmental targets

Source: New analysis based on estimates of food demand from the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations [56] and a database of country and food group-specific environmental footprints. The target values for sustainable food production that would be in line with Sustainable Development Goals were specified by and adapted from the EAT-Lancet Commission.

Note: In this test, regional diets in 2010 and 2018 are universally adopted and compared to global environmental targets.

- Download data: Figure 2.6

The past decade has seen little progress in improving diets, especially in low-income countries. Diets everywhere continue to lack enough fruits, vegetables, legumes, nuts and whole grains, and include too much – and, in some regions, rising amounts – of red and processed meat and sugary drinks. As a result, premature mortality related to dietary risks is substantial and increasing. Our analysis based on 11 diet and weight-related risk factors suggests that a quarter of all deaths among adults are associated with poor diets. The diet-related contribution to mortality is largest in higher-income countries, but the leading causes of dietary ill health are similar and increasing in every region.

The environmental impacts related to dietary choices are similarly daunting. According to our analysis, the foods currently demanded generate more than a third of all greenhouse gas emissions and use substantial and rising amounts environmental resources, such as cropland, fresh water and nitrogen- and phosphorus-containing fertilisers. Neither the global food system nor the various regional dietary patterns are on track to meet targets for sustainable food production and the set of diet-related health and environmental targets agreed by the international community of nations as part of the Sustainable Development Goals.

Part of the reason for the poor health and environmental performance of the food system might be a mismatch between current policy initiatives and the dietary and food-system changes that would be most beneficial for increasing the food system’s healthiness and sustainability. For example, recent years have seen many initiatives aimed at discouraging the consumption of sugary drinks by increasing their prices. [57] [58] Our analysis suggests that the health burden attributable to red and processed meat is more than six times as large as that associated with sugary drinks. Extending policy initiatives to these foods therefore warrants serious consideration from a public health perspective.

There are similar mismatches when it comes to the environmental impacts of our diets. Our analysis and past assessments indicate that most impacts occur at the production stage, with largest differences between food types, especially between animal- and plant-based foods, irrespective of the type of production system. [59] [60] Initiatives to improve production methods, reduce food loss and waste, and improve supply chains can be important measures for reducing environmental resource use. However, for reducing greenhouse gas emissions enough to avoid dangerous levels of global warming, it will be necessary to increase and strengthen policy initiatives aimed at reducing the amounts of animal-based foods in our diets and in food production.

Key recommendations

With little progress in improving diets throughout the last decade, there is an urgent need in every region to address dietary risk factors and reduce diet-related deaths from non-communicable diseases.

To improve population health, policy measures are needed to support increased intake of health-promoting foods such as fruits and vegetables, whole grains, legumes and nuts/seeds, and reduce the intake of unhealthy foods such as red and processed meat and sugary beverages.

As the environmental impacts of current dietary patterns are increasing, there is an urgent need in every region for large-scale dietary changes towards healthy and sustainable diets to preserve planetary health.

To improve planetary health, policy measures are required to transform the food system towards healthy and sustainable food production by prioritising adoption of healthy and sustainable diets and disincentivising the production and consumption of high-impact foods such as meat and dairy.

To transition towards healthy and sustainable diets and make meaningful progress, policy priorities need to align the dietary and food system changes most beneficial for health and the sustainability of the food system.

To reduce greenhouse gas emissions enough to avoid dangerous levels of global warming, it will be necessary to prioritise policy initiatives aimed at reducing the amounts of animal-based foods in our diets, something also warranted on health grounds.

Share What we eat matters: Health and environmental impacts of diets worldwide

- English Chapter 2_2021 Global Nutrition Report (PDF 836.1kB) 2021 Global Nutrition Report (PDF 3.9MB) Launch presentation - 2021 Global Nutrition Report (PDF 1.5MB)

- French Chapitre 2 2021 Rapport sur la Nutrition Mondiale (PDF 621.7kB) 2021 Global Nutrition Report French (PDF 3.1MB)

- Spanish Capítulo 2 2021 Informe de la Nutricion Mundial (PDF 608.6kB) 2021 Global Nutrition Report Spanish (PDF 3.0MB)

Download the 2021 Global Nutrition Report

Willett W, Rockström J, Loken B, et al. Food in the Anthropocene: the EAT–Lancet Commission on healthy diets from sustainable food systems. Lancet 2019; 393: 447–92.

IPCC. Climate Change and Land: An IPCC special report on climate change, desertification, land degradation, sustainable land management, food security, and greenhouse gas fluxes in terrestrial ecosystems. IPCC, 2019.

Afshin A, Sur PJ, Fay KA, et al. Health effects of dietary risks in 195 countries, 1990–2017: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017. Lancet 2019; 393: 1958–72 (doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(19)30041-8).

Murray CJL, Aravkin AY, Zheng P, et al. Global burden of 87 risk factors in 204 countries and territories, 1990–2019: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. Lancet 2020; 396: 1223–49.

Springmann M, Clark M, Mason-D’Croz D, et al. Options for keeping the food system within environmental limits. Nature 2018; 562: 519–25.

Willett WC, Stampfer MJ. Current evidence on healthy eating. Annu Rev Public Health 2013; 34: 77–95.

Mozaffarian D, Appel LJ, Horn LV. Components of a cardioprotective diet. Circulation 2011; 123: 2870–91.

Katz DL, Meller S. Can we say what diet is best for health? Annu Rev Public Health 2014; 35: 83–103.

Springmann M, Wiebe K, Mason-D’Croz D, Sulser TB, Rayner M, Scarborough P. Health and nutritional aspects of sustainable diet strategies and their association with environmental impacts: a global modelling analysis with country-level detail. Lancet Planet Health 2018; 2: e451–61.

Wang DD, Li Y, Afshin A, et al. Global improvement in dietary quality could lead to substantial reduction in premature death. J Nutr 2019; 149: 1065–74.

Satija A, Yu E, Willett WC, Hu FB. Understanding nutritional epidemiology and its role in policy. Adv Nutr 2015; 6: 5–18.

Bechthold A, Boeing H, Schwedhelm C, et al. Food groups and risk of coronary heart disease, stroke and heart failure: a systematic review and dose-response meta-analysis of prospective studies. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr 2019; 59: 1071–90.

Schwingshackl L, Hoffmann G, Lampousi AM, et al. Food groups and risk of type 2 diabetes mellitus: a systematic review and meta-analysis of prospective studies. Eur J Epidemiol 2017; 32: 363–75.

Schwingshackl L, Schwedhelm C, Hoffmann G, et al. Food groups and risk of colorectal cancer. Int J Cancer 2018; 142: 1748–58.

Micha R, Shulkin ML, Peñalvo JL, et al. Etiologic effects and optimal intakes of foods and nutrients for risk of cardiovascular diseases and diabetes: systematic reviews and meta-analyses from the Nutrition and Chronic Diseases Expert Group (NutriCoDE). PLoS One 2017; 12: e0175149.

World Cancer Research Fund/American Institute for Cancer Research. Diet, Nutrition, Physical Activity and Cancer: A Global Perspective. Continuous Update Project Expert Report. World Cancer Research Fund International, 2018.

Aune D, Norat T, Romundstad P, Vatten LJ. Dairy products and the risk of type 2 diabetes: a systematic review and dose-response meta-analysis of cohort studies. Am J Clin Nutr 2013; 98: 1066–83.

Aune D, Lau R, Chan DSM, et al. Dairy products and colorectal cancer risk: a systematic review and meta-analysis of cohort studies. Ann Oncol Off J Eur Soc Med Oncol 2012; 23: 37–45.

Xun P, Qin B, Song Y, et al. Fish consumption and risk of stroke and its subtypes: accumulative evidence from a meta-analysis of prospective cohort studies. Eur J Clin Nutr 2012; 66: 1199–207.

Zhao L-G, Sun J-W, Yang Y, Ma X, Wang Y-Y, Xiang Y-B. Fish consumption and all-cause mortality: a meta-analysis of cohort studies. Eur J Clin Nutr 2016; 70: 155–61.

Jayedi A, Shab-Bidar S, Eimeri S, Djafarian K. Fish consumption and risk of all-cause and cardiovascular mortality: a dose-response meta-analysis of prospective observational studies. Public Health Nutr 2018; 21: 1297–306.

Guasch-Ferré M, Satija A, Blondin SA, et al. Meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials of red meat consumption in comparison with various comparison diets on cardiovascular risk factors. Circulation 2019; 139: 1828–45.

Poore J, Nemecek T. Reducing food’s environmental impacts through producers and consumers. Science 2018; 360: 987–92.

Clark M, Tilman D. Comparative analysis of environmental impacts of agricultural production systems, agricultural input efficiency, and food choice. Environ Res Lett 2017; 12: 064016.

Clark MA, Springmann M, Hill J, Tilman D. Multiple health and environmental impacts of foods. Proc Natl Acad Sci 2019; 116: 23357–62.

Mekonnen MM, Hoekstra AY. A global assessment of the water footprint of farm animal products. Ecosystems 2012; 15: 401–15.

Clark MA, Domingo NGG, Colgan K, et al. Global food system emissions could preclude achieving the 1.5° and 2°C climate change targets. Science 2020; 370: 705–8.

Rosenzweig C, Mbow C, Barioni LG, et al. Climate change responses benefit from a global food system approach. Nat Food 2020; 1: 94–7.

Miller V, Singh GM, Onopa J, et al. Global Dietary Database 2017: data availability and gaps on 54 major foods, beverages and nutrients among 5.6 million children and adults from 1220 surveys worldwide. BMJ Glob Health 2021; 6: e003585.

NCD Risk Factor Collaboration (NCD-RisC). Trends in adult body-mass index in 200 countries from 1975 to 2014: a pooled analysis of 1698 population-based measurement studies with 19.2 million participants. Lancet 2016; 387: 1377–96.

Springmann M, Spajic L, Clark MA, et al. The healthiness and sustainability of national and global food based dietary guidelines: modelling study. BMJ 2020; 370: 2322.

Springmann M, Clark M, Rayner M, Scarborough P and Webb P. The global and regional costs of healthy and sustainable dietary patterns: a modelling study. Lancet 2021; 5: 797-807. (doi:10.1016/S2542-5196(21)00251-5).

Springmann M. Valuation of the health and climate-change benefits of healthy diets: Background paper for The State of Food Security and Nutrition in the World 2020. Rome, Italy: FAO, 2020 (doi:10.4060/cb1699en).

Roth GA, Abate D, et al. Global, regional, and national age-sex-specific mortality for 282 causes of death in 195 countries and territories, 1980–2017: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017. Lancet 2018; 392: 1736–88.

Aune D, Keum N, Giovannucci E, et al. Nut consumption and risk of cardiovascular disease, total cancer, all-cause and cause-specific mortality: a systematic review and dose-response meta-analysis of prospective studies. BMC Med 2016; 14: 207.

Aune D, Giovannucci E, Boffetta P, et al. Fruit and vegetable intake and the risk of cardiovascular disease, total cancer and all-cause mortality: a systematic review and dose-response meta-analysis of prospective studies. Int J Epidemiol 2016; published online 18 March.

Di Angelantonio E, Bhupathiraju S, et al. Body-mass index and all-cause mortality: individual-participant-data meta-analysis of 239 prospective studies in four continents. Lancet 2016; 388: 776–86.

Aune D, Keum N, Giovannucci E, et al. Whole grain consumption and risk of cardiovascular disease, cancer, and all cause and cause specific mortality: systematic review and dose-response meta-analysis of prospective studies. BMJ 2016; 353: i2716.

Imamura F, O’Connor L, Ye Z, et al. Consumption of sugar sweetened beverages, artificially sweetened beverages, and fruit juice and incidence of type 2 diabetes: systematic review, meta-analysis, and estimation of population attributable fraction. BMJ 2015; 351: h3576.

Xi B, Huang Y, Reilly KH, et al. Sugar-sweetened beverages and risk of hypertension and CVD: a dose-response meta-analysis. Br J Nutr 2015; 113: 709–17.

Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. Food Balance Sheets: A Handbook. Rome, Italy: FAO, 2001.

Allcott H, Lockwood BB, Taubinsky D. Should we tax sugar-sweetened beverages? An overview of theory and evidence. J Econ Perspect 2019; 33: 202–27.

Afshin A, Penalvo JL, Del Gobbo L, et al. The prospective impact of food pricing on improving dietary consumption: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One 2017; 12 (e0172277 %U https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/28249003 ).

What Shall We Eat? An Ethical Framework for Well-Grounded Food Choices

- Open access

- Published: 05 March 2020

- Volume 33 , pages 283–297, ( 2020 )

Cite this article

You have full access to this open access article

- Anna T. Höglund ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-4069-812X 1

8131 Accesses

7 Citations

16 Altmetric

Explore all metrics

In production and consumption of food, several ethical values are at stake for different affected parties and value conflicts in relation to food choices are frequent. The aim of this article was to present an ethical framework for well-grounded decisions on production and consumption of food, guided by the following questions: Which are the affected parties in relation to production and consumption of food? What ethical values are at stake for these parties? How can conflicts between the identified values be handled from different ethical perspectives? Four affected parties, relevant for both production and consumption of food, were identified, namely animals, nature, producers and consumers. Working form a bottom-up perspective, several values for these parties were identified and discussed. For animals: welfare, not being exposed to pain and natural behavior ; for nature: low negative impact on the environment and sustainable climate ; for producers: fair salaries and safe working conditions ; and for consumers: access to food, autonomy, health and food as part of a good life . As several of these values can come into conflict when choices of what to eat should be made, the article argues for the need of weighing values from four different perspectives in food ethics dilemmas, namely duties, consequences, virtues and care. The suggested ethical framework can provide moral guidance to both producers of food and to consumers in a supermarket. Thereby, it can contribute to more well-grounded decisions concerning what to eat and make people feel a little bit more secure when reflecting over the question: What shall we eat?

Similar content being viewed by others

Eating Ethically: Towards a Communitarian Food Model

Ethics of dietary guidelines: nutrients, processes and meals.

Ethical Perspectives on Food Morality: Challenges, Dilemmas and Constructs

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

To reflect ethically over what we eat has been part of Western culture for centuries. In his comprehensive exposé over Western food ethics, Zwart ( 2000 ) showed how dietetics was a prominent part already of the ethics in ancient Greece. For example, Plato reasoned over the place of food in human life in his book The Republic. He argued that food in itself was not a pleasure, although easily mistaken for such. Rather, Plato argued, it was the removal of pain in the form of hunger that was a pleasure, not food in itself (Plato 1955 ). Aristotle emphasized temperance in relation to food. Hence, dietetics was a central part of his ethics, where virtues and vices were at the fore. Aristotle’s position was that gluttony was a vice that should be avoided, whereas the virtue of temperance was what should be strived for and developed (Aristotle 1980 ).

Regulations around food are also common in the Old Testament. The distinction between allowed and not allowed food is central in the Hebrew Bible. For example, in Deuteronomy 14:3–7, it says that a Jew must not eat meat from animals that have cloven hoofs. In contrast to this, the New Testament does not include similar passages on legitimate and illicit food. On the contrary, in Matthew 15:11–17, Jesus proclaims that his followers should not be anxious about food or drink. Rather, food in the New Testament is a symbol of something sacred—as food should be blessed before intake—and of fellowship and solidarity, as for example signified in the Holy Communion.

During the middle ages, food ethics was predominantly elaborated within monastic contexts. Now, abstention from food intake became desirable. The mortification of the flesh was seen as a form of withdrawal from the sinful world. Through fasting, monks and nuns could distinguish themselves from the laity (Zwart 2000 ). However, Martin Luther, in his Table Talk , argued against this and instead recommended food as a remedy for melancholy and various temptations, if consumed in large quantities (Luther 2015 ).

In modern times, a scientific view dominated in food ethics. Further, the social dimension of food evolved, for example through the view that food intake could be a way of expressing your personality. Hence, vegetarianism became more common in the nineteenth century. Apart from this, the scientific view during modernity included attention to famine and injustice in the global distribution of food (Zwart 2000 ).

Whereas pre-modern food ethics mainly focused on aspects related to the consumption of food, today’s food ethics is more focused on the production of food. Therefore, topics such as animal ethics and ethical conflicts related to gene modified (GM) products have been well developed within the field. However, I argue that contemporary food ethics need also to include aspects of the meal, as what we eat can have social and cultural meaning (Tellström 2015 ; Höglund 2019 ).

In the introduction to his book The Ethics of Food , Gregory Pence states that “food makes philosophers of us all” (Pence 2002 , p. 6). By that he supposedly means that questions of what we eat tend to engage people and almost everyone has opinions about what is the “right” diet or type of food that should be served. Despite this, food ethics in its contemporary form did not emerge as a separate field in applied ethics until the 1990s. Often, Ben Mepham’s book Food Ethics from 1996 is mentioned as a starting point for this. For example, Zwart writes:

With the recent publication of the volume Food Ethics by Ben Mepham in 1996, a new branch of applied or professional ethics was introduced, but a long tradition of dietetics and other forms of moral concern with food preceded it. (Zwart 2000 , p. 114).

Zwart further points out, that it was in the late 1990s that this particular branch of applied ethics received its current label: “food ethics” (Zwart 2000 ).

In my book Vad ska vi äta? ( What Shall We Eat? ) from 2019, I observe that the debate on food and what we should eat often lacks a thorough ethical analysis (Höglund 2019 ). One explanation put forward in the book is that we might think that we have an ethical debate on producing and consuming food, as aspects of the environment, sustainability, climate change and animal welfare are included in the discussion, when in fact we are only discussing one issue at the time, without relating different values to each other. Nota bene : I do not claim that sustainability or animal welfare are not ethically relevant aspects—because they are—but I do claim that the debate on food production in many Western countries lacks a thorough ethical analysis, where different moral values are weighed against each other from different ethical perspectives. Further, I argue, that we need to include also the consumption of food in our ethical debates, as was the case in pre-modern food ethics, as described above.

Against this background, the aim of this article is to present an ethical framework for well-grounded ethical decisions regarding production and consumption of food. The investigation is guided by the following questions:

Which are the affected parties in relation to production and consumption of food?

What ethical values are at stake for these parties?

How can conflicts between the identified values be handled from different ethical perspectives?

A Matrix for Food Ethics

In his book Food Ethics , Ben Mepham ( 1996 ) suggested a matrix for an ethical analysis of food biotechnologies. The matrix starts out from a principled approach to ethics, building on Beauchamp’s and Childress’ well-known four principles, originally developed as prima facie obligations for health-care workers, namely autonomy, justice, non - maleficence and beneficence (Beauchamp and Childress 2009 ). With the attempt to apply these principles on food production, Mepham starts by identifying affected parties or interest groups in relation to the production of food. He admits that this is a complicated issue, in comparison to, for example, medical ethics where often one party is significantly affected by ethical decisions, namely the patient. But in relation to food the situation is different:

In food production, typically, millions of people (including producers, processors, retailers and consumers), the physical and biological environments and, often, non-human animals, are liable to be affected, one way or another, by decisions on a new technology (Mepham 1996 , p. 105).

Based on this, the affected parties Mepham identifies in his matrix of food ethics are the treated organism, the producers (e.g., farmers), the consumers and biota, defined as the animal and plant life of a region. He also adapts the ethical principles he has chosen so that they are meaningful to the identified interest groups. As the principles of non-maleficence and beneficence are “reciprocally related” (Mepham 1996 , p. 106) he chooses to combine them into “the principle of respect for well-being”. Apart from that, his matrix includes the principles of autonomy and justice.

Mephan argues that these ethical principles are important in various ways to the affected parties he has identified. For example, well-being for the treated organism is animal welfare. For the producers well-being means adequate income and good working conditions and for consumers it means availability of safe and healthy food. A simplified version of Mepham’s matrix is described in Table 1 .

I find Mepham’s matrix interesting, but also limited. Primarily, I argue that his analysis suffers from only including three ethical principles which are applied on four affected parties and thereby being developed from a top-down perspective. Second, it is limited through its focus on food biotechnologies. Thereby it is primarily relevant for the production of food, leaving several other aspects of food ethics ignored. Therefore—although inspired by Mepham—I have developed a somewhat different framework for food ethics, which I will describe in the following section. My analysis is made from a bottom-up approach and with a broader perspective, including both production and consumption of food.

Affected Parties and Values in Food Ethics

In agreement with Mepham, I argue that there are several affected parties in relation to food and that an ethical analysis needs to consider all these. In order to cover the ethics of both production and consumption of food, I have identified the following affected parties: animals, nature, producers and consumers . The first three are relevant for the production of food, as various producers make food from animals or plants, whereas the last one, consumers, is relevant for the consumption of food. But, instead of taking a top-down approach and doing an analysis from in advance chosen ethical principles, I intend to identify ethical values that can be at stake for these affected parties, building on the literature in the field, and discuss in what way these values are relevant for the different parties; thereby pursuing a more bottom-up approach.

I choose to label all aspects I discuss as “values”, well aware that they in the literature are also often described as principles. I choose “values”, though, as my attempt is to discuss how the identified aspects can be valuable for the different affected parties. The affected parties are not always moral subjects why it can be discussed whether, for example, nature can be an affected party as it cannot in itself have interests. However, for the sake of the argument, I have decided to treat all affected parties in the same way, seeking ethical values in relation to them that can be at stake in production or consumption of food.

The values I identify and discuss in the following build on previous research. Hence, my presentation summarizes a long history of deliberation concerning food ethics. I do claim, however, that my investigation sheds new light on these questions, particularly through the bottom-up approach and the ethical analysis I pursue in the last section of the article.

Hence, in the following, I will go through relevant ethical values for the affected parties animals, nature, producers and consumers .

To eat or not eat meat from animals might be to most heatedly debated question within food ethics. The arguments pro eating meat concern, for example, humans’ need for protein and other nutrients and that meat can be a source of that. Another argument is that people may think that meat tastes good and therefore choose to eat it. Apart from that, arguments justifying meat eating might also be that meat is suitable to humans, depending on the form of our teeth, the way we take up nutrients and what kind of food our body can handle (see e.g. Singer 2002 ). Finally, it can be argued, that for countries with cold climate—such as the Nordic countries—meat production was historically necessary for sufficient food production, as the cultivating of vegetables in large scale during the whole year was not possible in this part of the world. Today, breeding for meat production can be equally important in times of crisis. The Swedish agronomists Kersti Linderholm and Lennart Wikström argue:

People cannot eat grass, but ruminants can, and they transform the grass to nutritious food, like milk and meat. This has been a prerequisite for people to survive in the Swedish climate (Linderholm & Wikström 2019 ).

However, the ethical arguments contra meat eating are several, often based on values that are at stake for the animals. I will briefly go through some of them.

First, an important value for the affected party animals is that they should not be exposed to pain. This has been argued for by, among others, Singer and Mason ( 2007 ). They base their conclusions on a preference utilitarian arguing, where a basic assumption is that if a living being is capable to experience pain it has moral interests. A moral imperative is thus to act so that such living beings are not exposed to pain (Singer and Mason 2007 ).

A similar position is held by the philosopher Richard Ryder, who coined the concept “painism” (Ryder 2001 ). His arguing is based on rights, not interests and preferences as was the case for Singer and Mason. According to Ryder, living beings who can experience pain have intrinsic value. This means that they may not be used only as means to an end, but must always also be treated as ends in themselves. Thereby, they have a right to not being exposed to pain, according to this reasoning.

Another value for animals in food production is their right to natural behavior . However, this is a contested concept. The Swedish philosopher Pär Segerdahl has argued that it is not possible to separate domestic animals, such as cows, pigs or hens, from the context where they are bred. Hence, these animals have for centuries adopted to people and a domestic life. So, what is “natural” for such livestock, Segerdahl asks (Segerdahl 2009 ). This is an intriguing question. However, the Swedish law regarding protection of animals (Prop. 2017/18:147) states that natural behavior is behavior that domestic animals are highly motivated to and that is appropriate for their need for space, activity, rest and social context. Based on such a definition it is possible to argue that also the right to natural behavior is an important value for animals as an affected party in food ethics.

The right not to be exposed to pain as well as the right to natural behavior can both be seen as aspects of animal welfare. So, to sum up, the values that are at stake for the affected parties animals are welfare in the form of not being exposed to pain and possibilities to natural behavior.

For the second affected party in the presented food ethics analysis— nature —there are primarily two values that have been discussed in the literature; namely low negative impact on the environment and a sustainable climate . These two aspects are related, but can also be separated. Factory farming of animals for food production can violate the animals’ right to welfare, which has been discussed above, but it can also affect the environment in many ways. For example, large-scale factory farming can pollute the surrounding environment through emissions and use of energy from non-renewable resources (Singer and Mason 2007 ; Mepham 1996 ). Likewise, fish breeding can contribute to the pollution of seas, for example by toxins in the fish feed (Lövin 2010 ; Singer 2002 ).

Concerning sustainability and climate changes, it is today well established that breeding of cows and pigs give rise to high levels of CO 2 , which in turn can aggravate the climate change (Röös 2012 ). Apart from these direct influences, also transports of different kind need to be taken into account when analyzing environmental effects of production and consumption of food (Röös 2012 ). Transports by car or plane give rise to high levels of CO 2 and can come from both retailers and consumers.

The third affected party in the analysis are the producers of food. They can of course be of many kind, from big factories to small farmers. The values that can be at stake for food producers are quite similar, though, be they small or big, namely fair salaries and safe working conditions . Apart from that, all producers of food have an interest in making profit on their production, otherwise the production cannot continue. The ethical value, however, should not be profit but rather cost effectiveness, namely that resources are used efficiently and for relevant purposes (Höglund 2019 , p. 107).

Research has shown that work in animal factories can be both dangerous and underpaid (Singer 2002 ). Further, in countries with low salaries, often used as trading partners by industrial countries in order to cut prices, working conditions in food production in general can be very bad. In addition, child labor can occur in these countries (Singer 2002 ). In such cases, important ethical demands based on the values of fair salaries and safe working conditions are not fulfilled. According to Singer and Mason ( 2007 , p. 153), values related to producers of food can cause conflicts of interest between locally produced food and imported food. On the one hand, we might have an interest in supporting local farmers or industries. On the other, we might feel morally obliged to support farmers in developing countries by purchasing their products—provided that important ethical demands are fulfilled in their food production.

Finally, we have the consumers, that is, we who should eat the food. According to Coff ( 2006 , p. 78), a consumer is the person who consumes something that someone else has produced. For consumers of food, four values can be identified, namely access to food, autonomy, health and a good life.

Access to food as a right for everyone is stated in the United Nations’ Declaration of Human Rights. In Article 25 it says:

Everyone has the right to a standard of living adequate for the health and well-being of himself and his family, including food, clothing, housing and medical care and necessary social services.

In spite of this, access to food is not shared equally across the globe. In some parts of the world starvation is still a problem whereas in other areas obesity is the greatest challenge to public health. The duty to fulfill the right to food falls first and foremost on governments. However, one can claim that also individuals as citizens have a duty to support structures to meet the needs of the hungry (Telfer 1996 ). Access to food could also include work for social sustainability in a country, in order to secure food supply also in times of crisis (Linderholm and Wikström 2019 ).

When access to food is secured, the right to autonomy can be emphasized for the consumer. Often, this is interpreted as a freedom of choice for the individual (see e.g. Beauchamp and Childress 2009 ). In order to ensure this in relation to food, labelling has become more and more important, as disclosure of information about the available food is a presumption for consumer autonomy (Mepham 1996 , p. 110). Another aspect of consumer autonomy, put forward by Mepham, is voluntariness. However, to ensure voluntariness in the choice of food is not always so straight forward. As the Swedish ethicist Helena Röcklinsberg has argued, the fact that a consumer buys a product in his or her grocery shop cannot be taken for granted to be a consent to buy that exact product. She writes:

Consent by purchase is an uncertain mirror of consumer preferences, since such patterns express choice between available products, rather than consent to what is available (Röcklinsberg 2006 , p. 287).

Autonomy can be linked to the consumer’s right to healthy food. Here the requirement for labels is increased, as it is through labelling the consumer can get information of, for example, how the vegetables are cultivated. Regulations that prevent too high levels of toxins in food are also of utmost importance in order to fulfil the consumer’s right to healthy food.

Finally, one can state that in Western countries people spend more time and money on food than is needed to stay alive. Arguable, we do this because food gives us great pleasure. Hence, it is reasonable to argue that also well - being and food as a contribution to a good life are important values for the consumer. According to Elizabeth Telfer, to treat food as well-being is based on two rights for the individual: the right to safeguard one’s own happiness and the right to lead a worthwhile life (Telfer 1996 , p. 24). At first sight, these rights can be apprehended as opposites of the obligation mentioned above: to support structures to meet the needs of the hungry. However, in line with Telfer I argue, that these rights are compatible. Telfer writes:

In this book I have pointed out that for those of us who live in the first World, eating is usually not only a necessity but also a leisure activity, and I have claimed that we are justified in treating our food in this way. I have argued that we have real and extensive obligations to those who do not have enough to eat. But I have also claimed that we are entitled to aim at happiness and self-fulfillment, and that what we eat and how we regard food has an important part to play in the pursuit of both these aims (Telfer 1996 , p. 120).

In sum, for the affected party consumer the values at stake are access to food, autonomy, health and a good life. An overview of all identified affected parties and values is found in Table 2 .

Value Conflicts and Ethical Dilemmas

Apparently, several values for different affected parties are at stake in production and consumption of food. It is therefore not surprising that value conflicts occur frequently in food choices. For example, the value of low prices and producer profit can conflict with animal welfare. Organic farming can conflict with the goal of maximizing the harvest outcome and the value of climate sustainability can come into conflict with consumer autonomy. Et cetera , the list could be extended.

How are such value conflicts to be handled? I argue, that many of the identified value conflicts in relation to food can be interpreted as ethical dilemmas , where values of equal importance conflict and there are good reasons for preserving more than one of them. In such situations, a weighing of values from different ethical perspectives is necessary. In the following, I will illustrate how this can be done, from the perspective of four relevant and well-established ethical theories, namely deontology (or Kantian ethics), consequentialism (or utilitarianism), virtue (or Aristotelian) ethics and ethics of care.

The reasons for choosing these four perspectives are several. First, consequentialism and deontology are according to several text books the two principal contemporary theories of ethics (see e.g. Rachels 1993 ; Beauchamp and Childress 2009 ; Mepham 1996 ). Second, virtue ethics is by leading text books presented as the most pertinent alternative to these two grand theories (see e.g. Rachels 1993 ; Beauchamp and Childress 2009 ). Finally, apart from these three theoretical perspectives, I have chosen to investigate what a care ethics perspective can contribute to a food ethics analysis. In this case, I build on Held ( 2006 ), who has stated that the ethics of care can been seen as “a potential moral theory to be substituted for such dominant moral theories as Kantian ethics, utilitarianism, or Aristotelian virtue ethics” (Held 2006 , p. 9). Thereby, I find it relevant to discuss ethical dilemmas in food ethics, caused by conflicts between the identified values for affected parties, from these four ethical perspectives.

A moral duty is something that we have to do, not because it gives the best consequences or because we like it, but because it is the right thing to do. This is based on characteristics of the action itself. Some actions are our duty to perform, as they are morally right in themselves, such as to tell the truth or respect other people’s dignity. Such arguing is also called deontology , from the Greek word for duty, deon . As Immanuel Kant argued, we can judge an action as duty or not by the maxim behind the action (Kant 1996 ). Categorical “oughts”, according to this reasoning, are derived from principles that every rational person would accept (Rachels 1993 , p. 119). In Kant’s words: “Act only according to that maxim by which you can at the same time will that it should become a universal law” (Kant 1996 ; quoted in Rachels 1993 , p. 119). So, what duties can we have in relation to food ethics dilemmas?

According to Elizabeth Telfer, we have three kind of food duties, namely duties to others, to ourselves and to animals. Duties to other people contain primarily the requirement to help the hungry and to strive for justice in food distribution (Telfer 1996 , p. 61). Apart from this, I argue that one duty towards others in relation to food is respect . This includes respect for what is offered to eat, but also respect for people’s food choices and desires. Discussions on food tend to be emotional and value-laden, which can be avoided if the duty of respect is observed. Duties to other people could also include respect for future generations. Thereby, concerns about the environment and sustainability can be included in our food duties towards other people.

Duties towards ourselves are trickier, as it can be discussed whether we can have duties directed to ourselves (Telfer 1996 , p. 65). In line with Telfer, I claim that we can, and that in relation to food it is reasonable to argue that such duties are to exercise our autonomy, to eat healthy and to promote our self-development. The duty to eat healthy can also be seen as a duty towards other people, as unhealthy eating can lead to increased demands on healthcare, which in turn can tear on our common resources.

Concerning duties towards animals, they relate to the values discussed above, namely that animals in food production must not be exposed to stress and pain, but rather be allowed well-being and a natural behavior. However, our duties could also be extended to include respect for the animals’ right to life. Interpreted as such, the eating of meat becomes immoral. But, what if the duty to feed the hungry come into conflict with the moral demand of refraining from eating meat? In such situations, a hierarchy of duties is needed. In line with Elizabeth Telfer I argue, that our moral duties to other people come first in such situations, based on the Kantian principle of human dignity and respect for persons (Kant 1996 ). In Telfer’s words:

The thesis that we have a duty to refrain from eating meat seems to me one of the most important moral issues concerning food, second in importance only to our duty to help the hungry (Telfer 1996 , p. 61).

Telfer’s position is thus that we should refrain from eating meat, as she emphasizes the duty to respect animals so strongly. Against this, one could argue, that eating meat must not imply general disrespect towards animals. If treated respectfully, animals could be used for food production, as long as the ethical demands for well-being and natural behavior are fulfilled. Further, humans and domesticated animals have a long history together and animal husbandry does not by definition exclude respect for animals. Further, domesticated animals—such as cows and sheep—contribute to an open landscape which can help preserve biodiversity. Hence, one can argue that there is a mutual inter-dependence between humans and domesticated animals that is also of ethical value. Thereby, deontologically grounded respect for animal welfare can imply eating meat, and only if the respect is extended beyond animal well-being to the animals’ right to life, which seems to be the position Telfer holds, eating meat becomes immoral.

Apart from the three kind of food duties that Telfer has identified (to others, to ourselves and to animals), one can add that we can also have duties towards nature, as nature has been identified as an affected party in relation to food ethics. Duties to nature could of course overlap with duties to others, for example in the form of duties towards future generations, and to animals. But it is also possible to argue that we can have duties towards nature in itself, concerning for example the duty to preserve biodiversity.

Consequences

Apart from deontological aspects, also a consequentialist arguing can be a guiding perspective in some of the value conflicts and dilemmas that can occur in the production and consumption of food. In short, a consequentialist perspective means that an action is judged as moral or immoral based on its consequences. In the literature, such arguing is also called utilitarianism and derives from the theories developed by David Hume, Jeremy Bentham and John Stuart Mill. A basic assumption here is that morality is not a matter of following abstract rules, as was the case for Immanuel Kant, but of striving for as much happiness and utility as possible in the world. Therefore, our actions are judged as right or wrong depending on their consequences (Rachels 1993 , pp. 90–91).

Reflections over our actions’ consequences in relation to food are relevant when we, for example, consider whether to buy locally produced food or imported organic products. Through buying imported organic products, the consequences for the environment in the producing areas could be good, but at the same time, long transports could have affected the climate negatively. Further, the value of supporting local farmers and preserve an open landscape in our own country might be neglected when we buy imported food. Yet, another aspect that we might take into account from a consequentialist perspective concerns the possibility for a country to be self-sufficient with food in case of a crisis. From a consequentialist perspective, it is reasonable to hold that we from this perspective need to support our local food producers.

However, as in all consequence ethics, central questions to take into account from this perspective are: what consequences are we considering—the direct or the indirect ones? And for whom should the consequences be good? For myself and my close ones? Or for as many people as possible? And what about animals and the nature? In order to answer such questions, we need safe and correct information to build our decisions on. Unfortunately, this is not always the case when it comes to food. On the contrary, value-laden information is quite frequent in this area.

The ethics of virtue derives from Aristotle’s thinking in his Nicomachean Ethics (launched around 325 BC). Here, the central question is not what actions we should perform, but what a good person is like. Morality, according to this position, is thus about character (Aristotle 1980 ). A moral virtue can be described as a character trait that can be learned and developed, based on experience and good role models. In our lives, we should strive for such moral virtues and we can identify them as the middle path between two extremes (vices) that should be avoided. For example, courage is a virtue, and the related vices to be avoided are cowardice and arrogance or hubris. Hence, virtue ethics is more focused on what sort of persons we are, than on pursuing the right actions. Arguable, a good person performs the right actions (Rachels 1993 , p. 159 ff.).

According to Foot ( 1978 , pp. 1–18), a moral virtue possesses three features. First, it is a quality that a human being needs to have, “for his own sake and that of his fellows”. Second, it is a quality of will, rather than the intellect. Finally, a virtue can function as a correction of either excess or deficiency.

Moral virtues related to food that have been put forward in the literature are hospitality and temperance (Telfer 1996 ). Hospitality is mainly concerned with our relations to other persons, while temperance primarily concerns our own eating. To see hospitality as a food virtue means that one regards food as something that contributes to being a good person and that helps developing a good character. Not least, the act of the meal can be put forward as a situation that can contribute to the development of desired virtues, such as fellowship and solidarity between people. Thereby, hospitality as a virtue is closely related to the above mentioned duty to ensure every person’s right to food. It can be interpreted as fulfilling primarily the first two features in Foot’s definition of a virtue, namely to be virtues that every person needs to develop and to be qualities of the will (Foot 1978 ).

Temperance is a classic virtue, discussed already by Aristotle (384–322 BC). The vice (that is, the opposite that should be avoided) is gluttony. Hence, temperance fulfills especially the third criterion for a virtue above as defined by Philippa Foot, namely to function as a capacity to correct a common deficiency or excess in human motivation (Foot 1978 ; Telfer 1996 , p. 113). I argue, that temperance is a relevant virtue in relation to food ethics dilemmas, as it can ensure several values identified above. For example, it can contribute to health, as it prevents us from excessive eating and developing unhealthy obesity. It can also guide us to reduced meat eating, and thereby preserve several values identified for the affected party animals. Further, the virtue of temperance can contribute to preserving the value of sustainability, as it can encourage us to make use of the whole product when we cook and make us avoid throwing away food, and thereby not waste our common resources.

The ethics of care was developed in the 1980s, mainly in the USA (see e.g. Gilligan 1993 ; Noddings 2002 ). Within this tradition, the experience of giving and receiving care is regarded as morally valuable. The concept of care is defined both as a practice and as a moral value. Focus is on attending to and meeting the needs of “particular others”, for whom we are responsible (Held 2006 ). Further, care ethics acknowledges persons’ interdependence and the fact that we are all embedded in social contexts, characterized by power orders related to factors such as socio-economy and gender. Hence, the relational aspect is at the fore of this reasoning. Moral care does not only concern those who are close to us, but can embrace people in other parts of the world, as well as animals and the environment (Held 2006 ).