Goal Getting

What are process goals (with examples).

Ready. Set. Go. For years, this was my three-step mindset when it came to goals. I would reach for the moon and hope to land among the stars without feeling the pain of the fall. This approach was all or nothing, and as a result, I experienced loads of burnout and almost zero productivity. In short, my task list was filled with high-level intentions, but I hadn’t taken the time to create a map to reach the destinations. I was lost in the planning stages because I didn’t understand process goals or have any examples to follow.

Since then, I’ve learned how to embrace the journey and break my outcome goals into smaller and more manageable process goals. This approach has improved my focus and reduced frustration because I’m now working towards a surefire strategy that will take me where I want to go––I’m creating a plan of action with achievable daily targets (a process goal).

Table of Contents

What is a process goal, what is a destination goal, process goal template, what questions helped me find my process goals, what are some process goals you can try, what do you need for process goals, final thoughts.

A process goal is not a destination, it’s the path you plan on taking to get there. For example, if you want to become better at writing, your process goal would be to post one blog article per week and learn from the feedback you receive. The destination is a monthly goal of 12 articles.

This distinction is important because it’s easy to lose sight of the fact that these types of goals are not all or nothing. Think about it. You’ve heard it said: it’s not about working hard but working smart.

Well, a process goal is an actionable target with what we call SMART criteria:

- Specific – The more detailed your goal, the better. For example, instead of “I want to be fit,” you would say, “I want to lose five pounds.” Make sure your goal is crystal clear.

- Measurable – You need a way to measure progress and success, so it needs to be quantifiable. This is where you decide what “fit” actually means for you (more on this later).

- Achievable – If your goal isn’t challenging, then it’s not going to be motivating. On the other hand, there must be a steeper mountain to climb if you want substantial results.

- Realistic – “I want to run a marathon” is not practical for most people. Ensure you have the time, energy, and resources (e.g., training program) required to achieve your goal.

- Time-Bound – Your goal needs an assigned deadline or it’s just a pipe dream. There’s nothing wrong with dreaming, but what happens when the fantasy ends?

To summarize, these are the essential components of any process goal: specific, measurable, achievable within a certain time frame, and realistic.

A destination goal is a point in time when you plan to be at a particular destination. For example, if your goal is to get to represent your country at the 2025 Summer Olympics, you right need to focus on smaller increments to attain that success. On your way to that goal, you need to focus on smaller destinations. First, make the national team. Then, compete in a few events and so forth.

If you try to make it to the Olympics from the very start without any milestones along the way, it would be too daunting. On the other hand, if you focus on each milestone as a destination goal, it will all seem possible and achievable.

Let’s say you want to become a better cook. Here is one way of writing the process goal: “I will save $100 per week by cooking all my meals at home for 12 weeks.” This would be your destination (monthly), and the steps required to achieve this goal (weekly) would be:

- Spend one hour on Sunday planning my meals for the week.

- Shop for groceries after work on Monday and Tuesday nights.

- Cook all meals at home on Wednesdays through Sundays.

- Pack my lunch for work on Mondays and Tuesdays.

- Save $100 per week in cash by cooking at home.

This process goal will help you become a better cook by teaching you to save money through planning, shopping, cooking, packing your own lunch, and trying new recipes. It also includes a weekly reward (saving $100 in cash) that will help you stay motivated.

Process goals encourage you to reach your ultimate goals. When you feel like you can accomplish smaller goals along the way, you gain sustainability and confidence to move forward.

In many ways, process goals are a lot like faith. Each accomplishment brings you closer to seeing the fullness of the life that you desire––it breaks through the fog and makes things clearer.

After several years of setting lofty goals and becoming increasingly frustrated when I wasn’t getting the results I wanted, I decided to take a closer look at my approach.

Now, there are many ways you can do this, but here’s how I went about it. Last year, I asked myself the following questions:

- What am I doing right now?

- How can I get better at this?

- Is this process goal leading me closer to my ultimate goals?

The choices I made from the answers to these questions became my process goals. They were the driving force that kept me motivated and moving forward when I wanted to give up and throw in the towel. Since then, I’ve been able to accomplish lifelong goals that I had given up on years ago. For example, I’ve been able to obtain a publishing contract, create more digital products for my business, and enjoy the moment.

Before I broke down my goals into smaller ones, I was struggling to just get out of bed. The thought of my endless list kept me stagnant. Now, I look forward to each morning and taking on smaller projects to reach profitable outcomes.

So, now that you understand the importance of process goals, let’s get you started with some examples that you can utilize this week:

- Sign up for a new class.

- Complete one portion of your project by Thursday.

- Start walking around the block instead of running a mile.

- Improve your writing by spending 30 minutes everyday journaling.

- Practice your interview skills.

- Read at least one book from the library this week.

- Do ten push-ups each day before you leave for work.

You get the idea. These process goals don’t have to be complicated. If anything, you want to break down your plans to the point of them feeling easy or at least doable without needing a week’s vacation. By breaking your goals down into smaller pieces, you can accomplish a lot more in a shorter period. You’ll also feel more confident that you’re able to accomplish something within the moment.

It isn’t easy to continue towards your goal if achievement feels too far away. You need to celebrate the small things and embrace the process.

Think about how much time and money you’ve spent on new clothes, books, technology, etc. Many of us want to keep up with the latest trends and purchase the best gadgets from Apple or Microsoft. But all of these extra investments come at a steep price.

To find your process goals, you may have to face some difficult emotions or situations bravely and confront them head-on. You might need to forgo the new outfit or the latest Mac book to meet your overall objectives. Remember, process goals not only protect you from feeling overwhelmed, but they also keep you from being distracted.

You may feel overwhelmed at first when trying to set a process goal. Sometimes, just thinking about change triggers stress hormones, which only leads to more worries and anxious feelings. However, if you keep yourself focused and take small steps in the right direction, you’ll soon realize that goals don’t have to be complicated.

You can achieve your process goals one day at a time, and you can start today by breaking down your larger goal into smaller steps. It doesn’t matter if the process takes a week or six months, what matters most is that you’re moving forward and doing something to make yourself better.

Now, go on out there and achieve one of your process goals!

Introduction

What areas of life to set goals, the different types of goals, the power of long-term goals, the importance of short-term goals, what are intermediary goals for, what you need to know about process goals, goals vs objectives, why people fail to achieve their goals, how to set goals effectively, understanding smart goal setting, why are smart goals important, smart goal template, is willpower essential for reaching goals, how to achieve your goals, how to stay focused on your goals, life goals for success, personal goals examples, weekly goals you can set, professional goals & career goals, new year's resolutions ideas, best goal journals to keep track of progress, best goal tracking apps, inspiring quotes on setting goals, quotes to help you focus on goals, all goals articles.

Featured photo credit: Kaleidico via unsplash.com

How to Use a Planner Effectively

How to Be a Better Planner: Avoid the Planning Fallacy

5 Best Apps to Help You Delegate Tasks Easily

Delegating Leadership Style: What Is It & When To Use It?

The Fear of Delegating Work To Others

Why Is Delegation Important in Leadership?

7 Best Tools for Prioritizing Work

How to Deal with Competing Priorities Effectively

What Is the RICE Prioritization Model And How Does It Work?

4 Exercises to Improve Your Focus

What Is Chronic Procrastination and How To Deal with It

How to Snap Out of Procrastination With ADHD

Are Depression And Procrastination Connected?

Procrastination And Laziness: Their Differences & Connections

Bedtime Procrastination: Why You Do It And How To Break It

15 Books on Procrastination To Help You Start Taking Action

Productive Procrastination: Is It Good or Bad?

The Impact of Procrastination on Productivity

How to Cope With Anxiety-Induced Procrastination

How to Break the Perfectionism-Procrastination Loop

15 Work-Life Balance Books to Help You Take Control of Life

Work Life Balance for Women: What It Means & How to Find It

6 Essential Mindsets For Continuous Career Growth

How to Discover Your Next Career Move Amid the Great Resignation

The Key to Creating a Vibrant (And Magical Life) by Lee Cockerell

9 Tips on How To Disconnect From Work And Stay Present

Work-Life Integration vs Work-Life Balance: Is One Better Than the Other?

How To Practice Self-Advocacy in the Workplace (Go-to Guide)

How to Boost Your Focus And Attention Span

What Are Distractions in a Nutshell?

What Is Procrastination And How To End It

Prioritization — Using Your Time & Energy Effectively

Delegation — Leveraging Your Time & Resources

Your Guide to Effective Planning & Scheduling

The Ultimate Guide to Achieving Goals

How to Find Lasting Motivation

Complete Guide to Getting Back Your Energy

How to Have a Good Life Balance

Explore the time flow system.

About the Time Flow System

Key Philosophy I: Fluid Progress, Like Water

Key Philosophy II: Pragmatic Priorities

Key Philosophy III: Sustainable Momentum

Key Philosophy IV: Three Goal Focus

How the Time Flow System Works

SMART Goals in Education: Importance, Benefits, Limitations

Chris Drew (PhD)

Dr. Chris Drew is the founder of the Helpful Professor. He holds a PhD in education and has published over 20 articles in scholarly journals. He is the former editor of the Journal of Learning Development in Higher Education. [Image Descriptor: Photo of Chris]

Learn about our Editorial Process

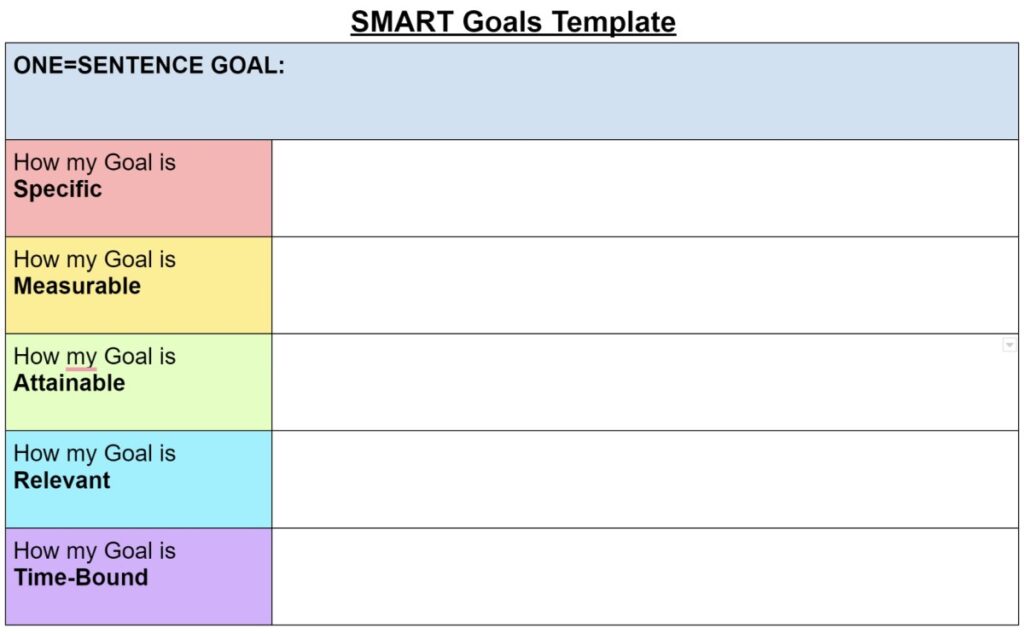

The SMART Goals framework is an acronym-based framework used in education to help students set clear and structured goals related to their learning.

The framework stands for:

- Specific – The goal is clear and has a closed-ended statement of exactly what will be achieved.

- Measurable – The goal can be measured either quantitatively (e.g. earning 80% in an exam) or qualitatively (e.g. receiving positive feedback from a teacher).

- Achievable – The goal is not too hard and can reasonably be met with some effort and within the set timeframe.

- Relevant – The goal is relevant to the student’s learning and development.

- Time-Based – A clear timeframe is set to keep you on task.

(If you’re a teacher, you might prefer to read my article on goals for teachers ).

The SMART Goals Framework in Education

The framework has had multiple variations over time. However, the most common framework is in the format: specific, measurable, attainable, relevant, and time-based.

1. Specific

Your goal needs to be specific. This means that you need to note a clear target to aspire toward rather than something that is vague.

For students, this is important to clarify exactly what it is you’re aiming for.

Some strategies for making sure your goal is specific include:

- State what, when, where, why, and how your goals will be achieved

- State what the goal will look like when it is achieved

- Focus on the “vital few” [1] things that you want to see done to have your goal achieved

Sometimes, this may also be stated as “strategic” rather than “specific”.

| Improve my English Speaking Skills | |

| Reach C1 Level in English Speaking on the IELTS test by May next year. |

See our in-depth article on examples of specific goals for students to get more ideas!

2. Measurable

Your goal needs to be measurable. This ensures that you can identify improvements from the baseline as well as know when the goal has been met.

Your objectives can be formative, summative, or a mix of both.

A formative assessment is an assessment that takes place part-way through the project. It assesses where you’re at and how much more you need to do. Formative assessments allow you to pivot and make small adjustments to your action to make sure you meet the final goal.

A summative assessment is an assessment at the end of the project to see if you met your goal. This is the final measure of success or failure.

A measurable goal may also be qualitative or quantitative.

A quantitative goal will have a grade or numerative evaluation, such as 80% on a test.

A qualitative goal will be based on a subjective evaluation, such as getting a positive report card from a mentor, or, attaining the confidence to do a public speech.

| Become a good academic writer. | |

| Gain an A grade on a college paper by the end of next semester. |

See our in-depth article on examples of measurable goals for students to get more ideas!

3. Attainable

Your goal needs to be attainable. This means that it can’t be something that’s impossible to achieve. You need to know you’ll be able to reach your goals in order to sustain motivation.

This could be compared to the goldilocks principle . Goldilocks didn’t like porridge that was too cold or too hot. It had to be just right.

In education, we use the Zone of Proximal Development (ZPD) to explain how to promote student development and motivation. The ZPD refers to learnable content that is not too easy and not too hard.

In this zone, students can do tasks with the support of teachers and have the motivation to work because they know the content is attainable with some effort.

| To learn the Spanish language in 7 days. | |

| To be able to recite the top 10 Spanish verbs from memory within 7 days. |

4. Relevant

Often also written as ‘realistic’, a relevant goal is one that makes sense to your situation. If you are setting goals in your class, your teacher would expect that the goal was about your education and not something irrelevant to class.

Your goal should also be one that is consistent with your life plan and will help you get to where you need to be. This will help you to sustain motivation and ensure the goal makes sense in the long term.

While having personal goals unrelated to your coursework is great, it’s not relevant to the lesson that you’re doing within the class on the day, so remember to set your goal so it’s related to your learning.

| To beat Level 7 of my video game on the weekend. | |

| To get an A+ on my Geography paper so I can sustain a GPA above 3.0. |

5. Time-Based

Setting a time by which you want to meet your goals helps to keep you on track and accountable to yourself. Without time-based end goals, you may delay your goals and lose momentum.

You can also set intermittent milestones to help keep yourself on track. This can ensure you don’t let other shorter-term and more pressing tasks get in the way and get you off track.

| To graduate from university. | |

| To complete 4 courses per semester and graduate from the university by November next year. |

SMARTER Goals Add-On

Some scholars have provided additional steps to the framework. One common one is to add ‘ER’ [2] :

6. Exciting

You are more likely to achieve a goal if you make it exciting. This will motivate you to carry out your plan.

An example of excitement added to a goal would be to create some self-rewards if it is completed, like “If I complete the goal I will take myself out for dinner.”

The ‘E’ is also often added when the goals are for teachers or leaders who are setting goals for their students or staff. By making the goal exciting, they’ll be able to get buy-in from students and staff.

7. Recorded

The ‘R’ often stands for ‘Recorded’ and asks you to show how you are going to record progress.

This one is somewhat similar to ‘Measurable’ but expands on it by asking not only how you’re going to measure success, but how are you going to record progress. Keeping a journal, for example, can help you record progress and reflect on the process of chasing your coals.

The Importance of SMART Goals in Education

Goal setting helps students and teachers to develop a vision for self-improvement . Without clear goals, there is no clear and agreed-upon direction for learning.

For this reason, goals have been used extensively in education. Examples include:

- Curriculum outcomes

- Developmental milestones

- Standardized testing

- Summative and formative assessments

The SMART framework, however, tends to be a student-led way of setting goals. It enables students to reflect on what they want to achieve and plan how to achieve these goals.

As a result, the framework doesn’t just help students articulate what they want out of their education. It also provides a range of soft skills for students such as:

- Motivation for growth

- Reflective practice

- Self Evaluation

- Structured analytical thinking

Read Also: Examples of SMART Goals for Students

SMART Goals Advantages and Disadvantages

Benefits of smart goals.

The SMART framework is widely used because it helps students to clarify their goals and how they are going to go about achieving them. Often, students start with a vague statement of intention, but by the end of the session, they have fleshed out their goals using the SMART template.

Some benefits of the template include:

| Students are given a framework to flesh out their goals and clarify them in their own minds. | |

| When using the framework, students can identify problems they may face, such as whether their timeframe is realistic or whether they have been specific enough. | |

| The framework can be understood and implemented within a single lesson. | |

| The framework isn’t only used for students but also in a wide range of other fields such as business, teaching, and leadership. | |

| There are many different iterations of the SMART framework (such as SMARTER) which can be used if the most common framework isn’t quite right in your situation. |

Limitations of SMART Goals

While the framework is easy to use and implement, it does face a few limitations. One major downside is that it doesn’t account for the importance of incrementalism in self-improvement. Students need to break down their goals into a series of milestones.

Some limitations of the template include:

| There is no clear consensus over what the ‘correct’ S.M.A.R.T acronym is. For example, sometimes the ‘R’ is realistic and other times it is relevant. Sometimes the ‘A’ is attainable and other times it is assignable. | |

| Goal setting should involve a series of short, medium, and that build upon one another. | |

| Other self-development frameworks such as the SWOT Analysis provide a stronger focus on barriers to success (both internal and external – see our list of ). By looking at barriers to success, you can predict them and work to mitigate their effects. |

SMART Goals Template

Get the Google Docs Template Here

SMART goals help students to reflect on what they want from their education and how to achieve it. They provide a template and framework for students to go into more depth about their goals so they are not simply vague statements, but rather actionable statements of intent.

A lesson where you get your students to set out their goals will often have students leaving the class with a much deeper understanding of what they want out of their education and how they might go about getting it.

Read Also: A List of Long-Term Goals for Students and A List of Short-Term Goals for Students

[1] O’Neil, J. and Conzemius, A. (2006). The Power of SMART Goals: Using Goals to Improve Student Learning . London: Solution Tree Press.

[2] Yemm, G. (2013). Essential Guide to Leading Your Team: How to Set Goals, Measure Performance and Reward Talent . Melbourne: Pearson Education. pp. 37–39.

- Chris Drew (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/chris-drew-phd/ 101 Class Group Name Ideas (for School Students)

- Chris Drew (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/chris-drew-phd/ 19 Top Cognitive Psychology Theories (Explained)

- Chris Drew (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/chris-drew-phd/ 119 Bloom’s Taxonomy Examples

- Chris Drew (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/chris-drew-phd/ All 6 Levels of Understanding (on Bloom’s Taxonomy)

Leave a Comment Cancel Reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

The Harriet W. Sheridan Center for Teaching and Learning

Establishing learning goals.

- Teaching Resources

- Course Design

Learning goals are the intended purposes and desired achievements of a particular course, which generally identify the knowledge, skills, and capacities a student in that class should achieve.

Why set learning goals?

- In a synthesis of over 800 meta-analyses about teaching and learning, educational researcher John Hattie (2011, p. 130) concludes that "having clear intentions and success criteria (goals)" is one of the key strategies that "works best" in improving student achievement in higher education.

- Being transparent about how and why students are learning in particular ways has been found to increase students' confidence, sense of belonging, and retention -- with key benefits for first-generation, low-income and underrepresented students ( Winkelmes, Bernacki, Butler, Zochowski, Golanics and Weavil, 2016 ).

What are examples of learning goals?

Three widely-used frameworks for learning goals include Bloom's Taxonomy, Fink's Taxonomy of Learning Experiences, and the Lumina Foundation's Degree Qualifications Profile.

- Bloom's Taxonomy sequences thinking skills from lower-order (e.g., remembering) to higher-order (e.g., evaluating, creating). (Bloom's Taxonomy was developed in 1956 and Anderson and Krathwohl created a revised taxonomy in 2001). This visual from Iowa State University's Center for Excellence in Learning and Teaching offers an example of learning goals keyed to Bloom levels .

- Dee Fink (2003) argues that faculty can create significant learning experiences when they address their students’ intellectual development holistically. Fink's Taxonomy of Significant Learning distinguishes six kinds of learning: 1) foundational knowledge, 2) application, 3) integration, 4) human dimensions (i.e. knowledge of self and others), 5) caring (i.e. appreciating or valuing the subject matter), and 6) learning how to learn. Section 5 of the US Air Force Academy’s “A Primer on Writing Effective Learner-Centered Course Goals” describes the taxonomy in more detail and provides verb stems and sample goals keyed to these six types of learning.

- The Lumina Foundations's Degree Qualifications Profile identifies specific learning outcomes for bachelor's and master's students in five categories: specialized knowledge, broad and integrative knowledge, intellectual skills, applied and collaborative learning, and civic and global learning. The process of "tuning" means adopting these broad outcomes to specific disciplines.

What are examples of learning goals at Brown?

- Brown's directory of Undergraduate Programs lists department undergraduate learning goals.

- Learning outcomes for anthropology , chemistry , economics , education and geology were established in the 2011-13 Sheridan Teagle Grant.

What self-directed resources can identify goals for my students' learning?

- Articulate Your Learning Objectives offers key steps (Carnegie Mellon University's Eberly Center for Teaching Excellence and Educational Innovation).

- Angelo and Cross's (1993) Teaching Goals Inventory offers a 53-item self-assessment to make explicit your implicit goals for student learning.

Anderson, L. W., & Krathwohl, D. R., et al. (Eds.) (2001). A taxonomy for learning, teaching, and assessing: A revision of Bloom's Taxonomy of Educational Objectives . Boston, MA: Allyn & Bacon.

Angelo, T. A., & Cross, K. P. (1993). Classroom assessment techniques: A handbook for college teachers . San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Bloom, B. S. (1956). Taxonomy of educational objectives: The classification of educational goals. Handbook 1: Cognitive domain . New York: David McKay Co. Inc.

Fink, D. L. (2003). Creating significant learning experiences: An integrated approach to designing college courses . San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Hattie, J. (2011). Which strategies best enhance teaching and learning in higher education? In D. Mashek and E. Y. Hammer, Eds. Empirical research in teaching and learning: Contributions from social psychology (pp. 130-142). Oxford: Blackwell Publishing.

Winkelmes, M., Bernacki, M., Butler, J., Zochowski, M., Golanics, J., & Weavil, K.H. (2016). Teaching intervention that increases underserved college students' success. AAC&U Peer Review , 16(1/2). https://www.aacu.org/peerreview/2016/winter-spring/Winkelmes .

- Our Mission

What Is Education For?

Read an excerpt from a new book by Sir Ken Robinson and Kate Robinson, which calls for redesigning education for the future.

What is education for? As it happens, people differ sharply on this question. It is what is known as an “essentially contested concept.” Like “democracy” and “justice,” “education” means different things to different people. Various factors can contribute to a person’s understanding of the purpose of education, including their background and circumstances. It is also inflected by how they view related issues such as ethnicity, gender, and social class. Still, not having an agreed-upon definition of education doesn’t mean we can’t discuss it or do anything about it.

We just need to be clear on terms. There are a few terms that are often confused or used interchangeably—“learning,” “education,” “training,” and “school”—but there are important differences between them. Learning is the process of acquiring new skills and understanding. Education is an organized system of learning. Training is a type of education that is focused on learning specific skills. A school is a community of learners: a group that comes together to learn with and from each other. It is vital that we differentiate these terms: children love to learn, they do it naturally; many have a hard time with education, and some have big problems with school.

There are many assumptions of compulsory education. One is that young people need to know, understand, and be able to do certain things that they most likely would not if they were left to their own devices. What these things are and how best to ensure students learn them are complicated and often controversial issues. Another assumption is that compulsory education is a preparation for what will come afterward, like getting a good job or going on to higher education.

So, what does it mean to be educated now? Well, I believe that education should expand our consciousness, capabilities, sensitivities, and cultural understanding. It should enlarge our worldview. As we all live in two worlds—the world within you that exists only because you do, and the world around you—the core purpose of education is to enable students to understand both worlds. In today’s climate, there is also a new and urgent challenge: to provide forms of education that engage young people with the global-economic issues of environmental well-being.

This core purpose of education can be broken down into four basic purposes.

Education should enable young people to engage with the world within them as well as the world around them. In Western cultures, there is a firm distinction between the two worlds, between thinking and feeling, objectivity and subjectivity. This distinction is misguided. There is a deep correlation between our experience of the world around us and how we feel. As we explored in the previous chapters, all individuals have unique strengths and weaknesses, outlooks and personalities. Students do not come in standard physical shapes, nor do their abilities and personalities. They all have their own aptitudes and dispositions and different ways of understanding things. Education is therefore deeply personal. It is about cultivating the minds and hearts of living people. Engaging them as individuals is at the heart of raising achievement.

The Universal Declaration of Human Rights emphasizes that “All human beings are born free and equal in dignity and rights,” and that “Education shall be directed to the full development of the human personality and to the strengthening of respect for human rights and fundamental freedoms.” Many of the deepest problems in current systems of education result from losing sight of this basic principle.

Schools should enable students to understand their own cultures and to respect the diversity of others. There are various definitions of culture, but in this context the most appropriate is “the values and forms of behavior that characterize different social groups.” To put it more bluntly, it is “the way we do things around here.” Education is one of the ways that communities pass on their values from one generation to the next. For some, education is a way of preserving a culture against outside influences. For others, it is a way of promoting cultural tolerance. As the world becomes more crowded and connected, it is becoming more complex culturally. Living respectfully with diversity is not just an ethical choice, it is a practical imperative.

There should be three cultural priorities for schools: to help students understand their own cultures, to understand other cultures, and to promote a sense of cultural tolerance and coexistence. The lives of all communities can be hugely enriched by celebrating their own cultures and the practices and traditions of other cultures.

Education should enable students to become economically responsible and independent. This is one of the reasons governments take such a keen interest in education: they know that an educated workforce is essential to creating economic prosperity. Leaders of the Industrial Revolution knew that education was critical to creating the types of workforce they required, too. But the world of work has changed so profoundly since then, and continues to do so at an ever-quickening pace. We know that many of the jobs of previous decades are disappearing and being rapidly replaced by contemporary counterparts. It is almost impossible to predict the direction of advancing technologies, and where they will take us.

How can schools prepare students to navigate this ever-changing economic landscape? They must connect students with their unique talents and interests, dissolve the division between academic and vocational programs, and foster practical partnerships between schools and the world of work, so that young people can experience working environments as part of their education, not simply when it is time for them to enter the labor market.

Education should enable young people to become active and compassionate citizens. We live in densely woven social systems. The benefits we derive from them depend on our working together to sustain them. The empowerment of individuals has to be balanced by practicing the values and responsibilities of collective life, and of democracy in particular. Our freedoms in democratic societies are not automatic. They come from centuries of struggle against tyranny and autocracy and those who foment sectarianism, hatred, and fear. Those struggles are far from over. As John Dewey observed, “Democracy has to be born anew every generation, and education is its midwife.”

For a democratic society to function, it depends upon the majority of its people to be active within the democratic process. In many democracies, this is increasingly not the case. Schools should engage students in becoming active, and proactive, democratic participants. An academic civics course will scratch the surface, but to nurture a deeply rooted respect for democracy, it is essential to give young people real-life democratic experiences long before they come of age to vote.

Eight Core Competencies

The conventional curriculum is based on a collection of separate subjects. These are prioritized according to beliefs around the limited understanding of intelligence we discussed in the previous chapter, as well as what is deemed to be important later in life. The idea of “subjects” suggests that each subject, whether mathematics, science, art, or language, stands completely separate from all the other subjects. This is problematic. Mathematics, for example, is not defined only by propositional knowledge; it is a combination of types of knowledge, including concepts, processes, and methods as well as propositional knowledge. This is also true of science, art, and languages, and of all other subjects. It is therefore much more useful to focus on the concept of disciplines rather than subjects.

Disciplines are fluid; they constantly merge and collaborate. In focusing on disciplines rather than subjects we can also explore the concept of interdisciplinary learning. This is a much more holistic approach that mirrors real life more closely—it is rare that activities outside of school are as clearly segregated as conventional curriculums suggest. A journalist writing an article, for example, must be able to call upon skills of conversation, deductive reasoning, literacy, and social sciences. A surgeon must understand the academic concept of the patient’s condition, as well as the practical application of the appropriate procedure. At least, we would certainly hope this is the case should we find ourselves being wheeled into surgery.

The concept of disciplines brings us to a better starting point when planning the curriculum, which is to ask what students should know and be able to do as a result of their education. The four purposes above suggest eight core competencies that, if properly integrated into education, will equip students who leave school to engage in the economic, cultural, social, and personal challenges they will inevitably face in their lives. These competencies are curiosity, creativity, criticism, communication, collaboration, compassion, composure, and citizenship. Rather than be triggered by age, they should be interwoven from the beginning of a student’s educational journey and nurtured throughout.

From Imagine If: Creating a Future for Us All by Sir Ken Robinson, Ph.D and Kate Robinson, published by Penguin Books, an imprint of Penguin Publishing Group, a division of Penguin Random House, LLC. Copyright © 2022 by the Estate of Sir Kenneth Robinson and Kate Robinson.

Additional Chapters

The learning process.

The learning process is something you can incite, literally incite, like a riot. —Audre Lorde, writer and civil rights activist

Learning Objectives

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- Identify the stages of the learning process

- Define learning styles, and identify your preferred learning style(s)

- Define multimodal learning

- Describe how you might apply your preferred learning strategies to classroom scenarios

Stages of the Learning Process

Consider experiences you’ve had with learning something new, such as learning to tie your shoes or drive a car. You probably began by showing interest in the process, and after some struggling it became second nature. These experiences were all part of the learning process, which can be described in the four stages:

- Unconscious incompetence : This will likely be the easiest learning stage—you don’t know what you don’t know yet. During this stage, a learner mainly shows interest in something or prepares for learning. For example, if you wanted to learn how to dance, you might watch a video, talk to an instructor, or sign up for a future class. Stage 1 might not take long.

- Conscious incompetence : This stage can be the most difficult for learners, because you begin to register how much you need to learn—you know what you don’t know. Think about the saying “It’s easier said than done.” In stage 1 the learner only has to discuss or show interest in a new experience, but in stage 2, he or she begins to apply new skills that contribute to reaching the learning goal. In the dance example above, you would now be learning basic dance steps. Successful completion of this stage relies on practice.

- Conscious competence : You are beginning to master some parts of the learning goal and are feeling some confidence about what you do know. For example, you might now be able to complete basic dance steps with few mistakes and without your instructor reminding you how to do them. Stage 3 requires skill repetition.

- Unconscious competence : This is the final stage in which learners have successfully practiced and repeated the process they learned so many times that they can do it almost without thinking. At this point in your dancing, you might be able to apply your dance skills to a freestyle dance routine that you create yourself. However, to feel you are a “master” of a particular skill by the time you reach stage 4, you still need to practice constantly and reevaluate which stage you are in so you can keep learning. For example, if you now felt confident in basic dance skills and could perform your own dance routine, perhaps you’d want to explore other kinds of dance, such as tango or swing. That would return you to stage 1 or 2, but you might progress through the stages more quickly this time on account of the dance skills you acquired earlier. [1]

Kyle was excited to take a beginning Spanish class to prepare for a semester abroad in Spain. Before his first vocabulary quiz, he reviewed his notes many times. Kyle took the quiz, but when he got the results, he was surprised to see that he had earned a B-, despite having studied so much.

Identifying Learning Styles

Many of us, like Kyle, are accustomed to very traditional learning styles as a result of our experience as K–12 students. For instance, we can all remember listening to a teacher talk, and copying notes off the chalkboard. However, when it comes to learning, one size doesn’t fit all. People have different learning styles and preferences, and these can vary from subject to subject. For example, while Kyle might prefer listening to recordings to help him learn Spanish, he might prefer hands-on activities like labs to master the concepts in his biology course. But what are learning styles, and where does the idea come from?

Learning styles are also called learning modalities . Walter Burke Barbe and his colleagues proposed the following three learning modalities (often identified by the acronym VAK):

- Kinesthetic

Examples of these modalities are shown in the table, below.

| Visual | Kinesthetic | Auditory |

|---|---|---|

| Picture | Gestures | Listening |

| Shape | Body Movements | Rhythms |

| Sculpture | Object Manipulation | Tone |

| Paintings | Positioning | Chants |

Neil Fleming’s VARK model expanded on the three modalities described above and added “Read/Write Learning” as a fourth.

The four sensory modalities in Fleming’s model are:

- Visual learning

- Auditory learning

- Read/write learning

- Kinesthetic learning

Fleming claimed that visual learners have a preference for seeing (visual aids that represent ideas using methods other than words, such as graphs, charts, diagrams, symbols, etc.). Auditory learners best learn through listening (lectures, discussions, tapes, etc.). Read/write learners have a preference for written words (readings, dictionaries, reference works, research, etc.) Tactile/kinesthetic learners prefer to learn via experience—moving, touching, and doing (active exploration of the world, science projects, experiments, etc.).

The VAK/VARK models can be a helpful way of thinking about different learning styles and preferences, but they are certainly not the last word on how people learn or prefer to learn. Many educators consider the distinctions useful, finding that students benefit from having access to a blend of learning approaches. Others find the idea of three or four “styles” to be distracting or limiting.

In the college setting, you’ll probably discover that instructors teach their course materials according to the method they think will be most effective for all students. Thus, regardless of your individual learning preference, you will probably be asked to engage in all types of learning. For instance, even though you consider yourself to be a “visual learner,” you will still probably have to write papers in some of your classes. Research suggests that it’s good for the brain to learn in new ways and that learning in different modalities can help learners become more well-rounded. Consider the following statistics on how much content students absorb through different learning methods:

- 10 percent of content they read

- 20 percent of content they hear

- 30 percent of content they visualize

- 50 percent of what they both visualize and hear

- 70 percent of what they say

- 90 percent of what they say and do

The range of these results underscores the importance of mixing up the ways in which you study and engage with learning materials.

Activity: Identifying Preferred Learning Styles

- Define learning styles, and recognize your preferred learning style(s)

- Now it’s time to consider your preferred learning style(s). Take the VARK Questionnaire here .

- Review the types of learning preferences.

- Identify three different classes and describe what types of activities you typically do in these classes. Which learning style(s) do these activities relate to?

- Describe what you think your preferred learning style(s) is/are. How do you know?

- Explain how you could apply your preferred learning style(s) to studying.

- What might your preferred learning style(s) tell you about your interests? Consider which subjects and eventual careers you might like.

- Follow your instructor’s guidelines for submitting your assignment.

Defining Multimodal Learning

While completing the learning-styles activity, you might have discovered that you prefer more than one learning style. Applying more than one learning style is known as multimodal learning. This strategy is useful not only for students who prefer to combine learning styles but also for those who may not know which learning style works best for them. It’s also a good way to mix things up and keep learning fun.

For example, consider how you might combine visual, auditory, and kinesthetic learning styles to a biology class. For visual learning, you could create flash cards containing images of individual animals and the species name. For auditory learning, you could have a friend quiz you on the flash cards. For kinesthetic learning, you could move the flash cards around on a board to show a food web (food chain).

The following video will help you review the types of learning styles and see how they might relate to your study habits:

The next assignment can help you extend and apply what you’ve learned about multimodal learning to current classes and studying.

Activity: Applying Learning Styles to Class

- Apply your preferred learning styles to classroom scenarios

- Review the three main learning styles and the definition of multimodal learning.

- Identify a class you are currently taking that requires studying.

- Describe how you could study for this class using visual, auditory, and kinesthetic/tactile learning skills.

- Follow your instructor’s guidelines for submitting your activity.

- Mansaray, David. "The Four Stages of Learning: The Path to Becoming an Expert." DavidMansaray.com . 2011. Web. 10 Feb 2016. ↵

- The Learning Process. Authored by : Jolene Carr. Provided by : Lumen Learning. License : CC BY: Attribution

- Learning Styles. Provided by : Wikipedia. Located at : https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Learning_styles . License : CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- SU13_KentLeach_MT_Edit (29 of 65). Provided by : UC Davis College of Engineering. Located at : https://www.flickr.com/photos/ucdaviscoe/9731984405/ . License : CC BY: Attribution

- The Process of Learning - Kristos. Authored by : calikristos. Located at : https://youtu.be/G1eQ6JWAi9Q . License : All Rights Reserved . License Terms : Standard YouTube License

- Discover Your Learning Style and Optimize Your Self Study. Authored by : Langfocus. Located at : https://youtu.be/dvMex7KXLvM . License : All Rights Reserved . License Terms : Standard YouTube License

- Skip to main content

- Skip to search

- Skip to footer

Center for Engaged Learning

Process-driven model of education.

by Ketevan Kupatadze

October 10, 2017

In this blog I will continue reflecting on the various ways in which the student-faculty partnership model could challenge or simply take a different approach towards the established higher education system. Here I focus on Students-as-Partner’s emphasis on the open and unpredictable process of teaching and learning rather than the predetermined teaching and learning goals and outcomes. There seems to exist a slight disconnect between the policies at the institutional as well as supra-institutional levels that aim to assure the quality and standards of education through continuous assessment and the pedagogical philosophy rooted in the principles of partnership between students and educators. Two possible solutions to such disconnect seem to be a) the acceptance of education as at times an unpredictable and changeable process, and b) the development of tools and resources that would help us assess or evaluate the learning that happens through partnership.

In “A Model of Active Student Participation in Curriculum Design: Exploring Desirability and Possibility,” Bovill and Bulley (2011) state that “our systems of quality assurance require courses to be validated and reviewed on the basis of clear intended learning outcomes and assessments” (p. 6). In the same vein, Healey, Flint and Harrington (2014) recognize the important role of the institutions and professional organizations that set the guidelines and standards for educational goals and outcomes. Without a doubt, our focus on teaching and learning goals and outcomes and their assessment has a long-standing tradition and will be incredibly hard and, more importantly, counterproductive to discard. But at the same time, the advocates of student-faculty partnership in teaching and leaning view this practice as a process rather than as a goal and outcomes-driven activity and, as such, one that has the potential to dramatically transform the purpose and structure of higher education that is largely based on delivering results in the form of outcomes through assessment (Healey et al., 2014). Healey et al. maintain that unlike the current model that is end-oriented, the student-faculty partnership is pedagogy that is “(radically) open to and creating possibilities for discovering and learning something that cannot be known beforehand”(2014, p. 9).

This opinion is also shared by Matthews (2016) who acknowledges that SaP model is inherently process-oriented rather than outcomes-driven (p. 3). She maintains that the language of student engagement has been and remains outcomes focused, while Students as Partners is process and values oriented (p. 3). The question then is: how does one engage in student-faculty partnership, opening up to the possibility of not knowing the end-point of teaching and learning whether in a specific course, set of courses or an entire curriculum and, simultaneously, continue assessing student learning to ensure that the standards set by their institution or professional organization(s) are met?

To answer these questions, several studies have pointed out that we might, and even should, be having a conversation on the ways to incorporate assessment in the student-faculty partnership process (Cook-Sather et al. 2014; Healey et al. 2014;). Healey et al suggest that to address this issue we might “look for opportunities for employing partnership as a way of responding to other influential discourses; use the concept and practice of partnership to meet the requirements” set out by our institutions and/or professional organizations; and “consider how reward and recognition for partnership may be developed” (p. 58). Cook-Sather et al., on their part, suggest that assessment should be also co-envisioned and co-developed by faculty and students as partners, since it is an integral part of teaching and learning process (p. 188). The authors offer various examples: involvement of students in the design of course learning goals and outcomes, such as inviting students to develop course goals either in the beginning or the end of the term; inviting them to reflect on their end of course feedback; involving them in the process itself of developing assignment, course, or curriculum assessment such as end-of-term course evaluation questionnaires and course assessment tools while the course is in progress; offering students an opportunity to reflect on their learning throughout the course; working with students outside the class setting to assess learning across courses, etc.

This conversation about the ways to partner with students on assessment as a valued part of the teaching and learning process is new and ongoing. It is one of the areas that needs most attention as we move towards a more egalitarian educational model in which we – faculty and students – see each other as partners and collaborators. I would be curious to know of different ways one could partner with students to teach, while simultaneously making sure that the educational standards are met through continuous process of assessing instructors’ and students’ teaching and learning goals.

Bibliography

- Bovill, C., and Bulley, C.J. (2011) A model of active student participation in curriculum design: exploring desirability and possibility. In Rust, C. (ed.) Improving Student Learning (ISL) 18: Global Theories and Local Practices: Institutional, Disciplinary and Cultural Variations. Series: Improving Student Learning (18). Oxford Brookes University: Oxford Centre for Staff and Learning Development: Oxford, pp. 176-188. ISBN 9781873576809

- Cook-Sather, A., Bovill, C., and Felten, P. (2014). Engaging students as partners in learning and teaching: a guide for faculty. San Francisco, California: Jossey-Bass.

- Healey, M., Flint, A., & Harrington, K. (2014). Engagement through partnership: Students as partners in learning and teaching in higher education. York: Higher Education Academy. Retrieved from https://www.heacademy.ac.uk/engagement-through-partnership-students-partners-learning-and-teaching-higher-education

- Matthews, K. E. (2016). Students as partners as the future of student engagement. Student Engagement in Higher Education Journal, 1 (1) 1-5. Retrieved from https://journals.gre.ac.uk/index.php/raise/article/view/380/338

Ketevan Kupatadze, Senior Lecturer in Spanish in the Department of World Languages and Cultures, is the 2017-2019 Center for Engaged Learning Scholar . Dr. Kupatadze’s CEL Scholar project focuses on student-faculty partnerships.

How to cite this post:

Kupatadze, Ketevan. 2017, October 10. Process-Driven Model of Education. [Blog Post]. Retrieved from https://www.centerforengagedlearning.org/process-driven-model-of-education/

- Engaged Learning

- Student-Faculty Partnership

- Ketevan Kupatadze

Lorem ipsum test link amet consectetur a

Goal Setting: Outcome, Performance and Process Goals

In this article:

The process of goal setting based on outcome, performance and process goals comes from the world of athletics, but is equally applicable to business and personal development. Whether you are an athlete or the CEO of a business, this article will give you the tools you need to start planning like an athlete.

Why Should We Set Goals?

Having short and long term goals can have a number of benefits, including:

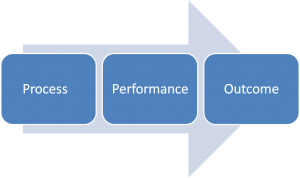

There are three types of goals: outcome, performance and process goals. Goal setting is broken down in this way as it makes it easier to organise our thinking around how we’re going to achieve our goals.

Outcome Goals

An outcome goal is the singular goal that you are working towards. Outcome goals are very often binary and involve winning, for example, wanting to win a gold medal or wanting to be the largest company in your sector. Whilst outcome goals are hugely motivating, they are not under your control as they are affected by how others perform. In a sporting sense this might mean that someone outperforms you on the field of play, and in a business sense this could happen if one of your key team members was ill or your competition outsmarted you.

Performance Goals

A performance goal is a performance standard that you are trying to achieve. These are the performance standards you set for yourself to achieve if you are going to build towards your outcome goal.

Their 2nd performance goal might be to:

Process Goals

Process goals support performance goals by giving you something to focus on as you work towards your performance goals. Process goals are completely under your control. They are the small things you should focus on or do to eventually achieve your performance goals.

Examples of process goals include:

Using SMARTER Goals

Both athletes and business people frequently set goals that are very difficult to measure, for example, “win a gold medal” or “win on mobile”. To avoid this trap make sure that all of your goals are SMARTER:

An Example from Sports

Let’s look at a complete example to really make this sink in. Let’s say you did want to finish top 10 in a local 5k running race, then your goals might look like this:

An Example from Business

Let’s look at a complete example from business to further build our understanding. Suppose our revenue is currently at $500k per month and we wanted to generate $1m revenue per month, then our goals might look like this.

Sometimes we set goals such as to win a gold medal, or to generate more revenue than our competitors this month, however, the reality is that we don’t actually have control over these goals, our competitors could compete better and win.

Using Outcome, Performance and Process Goals in Real Life

In addition to setting SMART goals as described above when setting outcome, performance and process goals, it can be a good idea to break down the timeline of achieving your outcomes into smaller blocks of time. A 2007 study by psychologist Richard Wiseman showed that 88% of people who make New Year’s resolutions fail. For this reason don’t make detailed long range plans focusing a year out or more. Instead stick to a shorter timescale like 13 weeks. There are a number of reasons to do this:

Goal Setting Template

Cite this article, related tools, the stages of change model, panas scale (positive and negative affect schedule), honey and mumford learning styles, perma model of well-being, cognitive restructuring, book summary: the lean startup by eric ries, benefits of goal setting, the dunning-kruger effect, book summary: atomic habits by james clear, in our course you will learn how to:.

This 5-week course will teach you everything you need to know to set up and then scale a small, part-time business that will be profitable regardless of what’s happening in the economy.

CALE Learning Enhancement

Eastern Washington University

Goal-Setting

What is goal setting?

There are three types of goals- process, performance, and outcome goals.

- Process goals are specific actions or ‘processes’ of performing. For example, aiming to study for 2 hours after dinner every day . Process goals are 100% controllable by the individual.

- Performance goals are based on personal standard. For example, aiming to achieve a 3.5 GPA. Personal goals are mostly controllable.

- Outcome goals are based on winning. For a college student, this could look like landing a job in your field or landing job at a particular place of employment you wanted. Outcome goals are very difficult to control because of other outside influences.

Process, performance, and outcome goals have a linear relationship. This is important because if you achieve your process goals, you give yourself a good chance to achieve your performance goals. Similarly, when you achieve your performance goals, you have a better chance of achieving your outcome goal.

General Goal Setting Tips

- set both short- and long-term goals

- set SMART goals

- set goals that motivate you

- write your goals down and put them in a place you can see

- adjust your goals as necessary

- Recognize and reward yourself when you meet a goal

Set SMART Goals

Set all three types of goals- process, performance, and outcome – but focus on executing your smaller process goals to give you the best chance for success!

- specific – highly detailed statement on what you want to accomplish (use who, what, where, how etc.)

- Measurable- how will you demonstrate and evaluate how your goal has been met?

- Attainable- they can be achieved by your own hard work and dedication- make sure your goals are within your ability to achieve

- Relevant- how does your goals align with your objectives?

- Time based- set 1 or more target dates- these are the “by whens” to guide your goal to successful and timely completion (include deadlines, frequency and dates)

Goal Setting Handout – Center for Performance Psychology

Applied Exercises

Goal Setting Worksheet

Goal Setting Worksheet – Center for Performance Psychology

Articles on Goal Setting

- Importance of Goal Setting

- Before Setting New Goals, Evaluate Previous Ones

Goal Setting Videos

This video discusses goal setting by the Academic Success Center at Oregon State University.

This video teaches you how to set short term weekly goals.

This video demonstrates goal setting one step at a time.

Campus Safety

509.359.6498 Office

509.359.6498 Cheney

509.359.6498 Spokane

Records & Registration

509.359.2321

Need Tech Assistance?

509.359.2247

EWU ACCESSIBILITY

509.359.6871

EWU Accessibility

Student Affairs

509.359.7924

University Housing

509.359.2451

Housing & Residential Life

Register to Vote

Register to Vote (RCW 29A.08.310)

509.359.6200

© 2023 INSIDE.EWU.EDU

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

3 The learning process

When my son Michael was old enough to talk, and being an eager but naïve dad, I decided to bring Michael to my educational psychology class to demonstrate to my students “how children learn”. In one task I poured water from a tall drinking glass to a wide glass pie plate, which according to Michael changed the “amount” of water—there was less now than it was in the pie plate. I told him that, on the contrary, the amount of water had stayed the same whether it was in the glass or the pie plate. He looked at me a bit strangely, but complied with my point of view—agreeing at first that, yes, the amount had stayed the same. But by the end of the class session he had reverted to his original position: there was less water, he said, when it was poured into the pie plate compared to being poured into the drinking glass. So much for demonstrating “learning”!

(Kelvin Seifert)

Learning is generally defined as relatively permanent changes in behavior, skills, knowledge, or attitudes resulting from identifiable psychological or social experiences. A key feature is permanence: changes do not count as learning if they are temporary. You do not “learn” a phone number if you forget it the minute after you dial the number; you do not “learn” to eat vegetables if you only do it when forced. The change has to last. Notice, though, that learning can be physical, social, or emotional as well as cognitive. You do not “learn” to sneeze simply by catching cold, but you do learn many skills and behaviors that are physically based, such as riding a bicycle or throwing a ball. You can also learn to like (or dislike) a person, even though this change may not happen deliberately.

Each year after that first visit to my students, while Michael was still a preschooler, I returned with him to my ed-psych class to do the same “learning demonstrations”. And each year Michael came along happily, but would again fail the task about the drinking glass and the pie plate. He would comply briefly if I “suggested” that the amount of water stayed the same no matter which way it was poured, but in the end he would still assert that the amount had changed. He was not learning this bit of conventional knowledge, in spite of my repeated efforts.

But the year he turned six, things changed. When I told him it was time to visit my ed-psych class again, he readily agreed and asked: “Are you going to ask me about the water in the drinking glass and pie plate again?” I said yes, I was indeed planning to do that task again. “That’s good”, he responded, “because I know that the amount stays the same even after you pour it. But do you want me to fake it this time? For your students’ sake?”

Teachers’ perspectives on learning

For teachers, learning usually refers to things that happen in schools or classrooms, even though every teacher can of course describe examples of learning that happen outside of these places. Even Michael, at age 6, had begun realizing that what counted as “learning” in his dad’s educator-type mind was something that happened in a classroom, under the supervision of a teacher (me). For me, as for many educators, the term has a more specific meaning than for many people less involved in schools. In particular, teachers’ perspectives on learning often emphasize three ideas, and sometimes even take them for granted: (1) curriculum content and academic achievement, (2) sequencing and readiness, and (3) the importance of transferring learning to new or future situations.

Viewing learning as dependent on curriculum

When teachers speak of learning, they tend to emphasize whatever is taught in schools deliberately, including both the official curriculum and the various behaviors and routines that make classrooms run smoothly. In practice, defining learning in this way often means that teachers equate learning with the major forms of academic achievement—especially language and mathematics—and to a lesser extent musical skill, physical coordination, or social sensitivity (Gardner, 1999, 2006). The imbalance occurs not because the goals of public education make teachers responsible for certain content and activities (like books and reading) and the skills which these activities require (like answering teachers’ questions and writing essays). It does happen not (thankfully!) because teachers are biased, insensitive, or unaware that students often learn a lot outside of school.

A side effect of thinking of learning as related only to curriculum or academics is that classroom social interactions and behaviors become issues for teachers—become things that they need to manage. In particular, having dozens of students in one room makes it more likely that I, as a teacher, think of “learning” as something that either takes concentration (to avoid being distracted by others) or that benefits from collaboration (to take advantage of their presence). In the small space of a classroom, no other viewpoint about social interaction makes sense. Yet in the wider world outside of school, learning often does happen incidentally, “accidentally” and without conscious interference or input from others: I “learn” what a friend’s personality is like, for example, without either of us deliberately trying to make this happen. As teachers, we sometimes see incidental learning in classrooms as well, and often welcome it; but our responsibility for curriculum goals more often focuses our efforts on what students can learn through conscious, deliberate effort. In a classroom, unlike in many other human settings, it is always necessary to ask whether classmates are helping or hindering individual students’ learning.

Focusing learning on changes in classrooms has several other effects. One, for example, is that it can tempt teachers to think that what is taught is equivalent to what is learned—even though most teachers know that doing so is a mistake, and that teaching and learning can be quite different. If I assign a reading to my students about the Russian Revolution, it would be nice to assume not only that they have read the same words, but also learned the same content. But that assumption is not usually the reality. Some students may have read and learned all of what I assigned; others may have read everything but misunderstood the material or remembered only some of it; and still others, unfortunately, may have neither read nor learned much of anything. Chances are that my students would confirm this picture, if asked confidentially. There are ways, of course, to deal helpfully with such diversity of outcomes; for suggestions, see especially Chapter 11 “Planning instruction” and Chapter 12 “Teacher-made assessment strategies”. But whatever instructional strategies I adopt, they cannot include assuming that what I teach is the same as what students understand or retain of what I teach.

Viewing learning as dependent on sequencing and readiness

The distinction between teaching and learning creates a secondary issue for teachers, that of educational readiness . Traditionally the concept referred to students’ preparedness to cope with or profit from the activities and expectations of school. A kindergarten child was “ready” to start school, for example, if he or she was in good health, showed moderately good social skills, could take care of personal physical needs (like eating lunch or going to the bathroom unsupervised), could use a pencil to make simple drawings, and so on. Table 2 shows a similar set of criteria for determining whether a child is “ready” to learn to read (Copple & Bredekamp, 2006). At older ages (such as in high school or university), the term readiness is often replaced by a more specific term, prerequisites. To take a course in physics, for example, a student must first have certain prerequisite experiences, such as studying advanced algebra or calculus. To begin work as a public school teacher, a person must first engage in practice teaching for a period of time (not to mention also studying educational psychology!).

Table 2: Reading readiness in students vs in teachers

|

|

|

| Copple & Bredekamp, 2006. | |

Note that this traditional meaning, of readiness as preparedness, focuses attention on students’ adjustment to school and away from the reverse: the possibility that schools and teachers also have a responsibility for adjusting to students. But the latter idea is in fact a legitimate, second meaning for readiness: If 5-year-old children normally need to play a lot and keep active, then it is fair to say that their kindergarten teacher needs to be “ready” for this behavior by planning for a program that allows a lot of play and physical activity. If she cannot or will not do so (whatever the reason may be), then in a very real sense this failure is not the children’s responsibility. Among older students, the second, teacher-oriented meaning of readiness makes sense as well. If a teacher has a student with a disability (for example, the student is visually impaired), then the teacher has to adjust her approach in appropriate ways—not simply expect a visually impaired child to “sink or swim”. As you might expect, this sense of readiness is very important for special education, so I discuss it further in Chapter 6 “Students with special educational needs”. But the issue of readiness also figures importantly whenever students are diverse (which is most of the time), so it also comes up in Chapter 5 “Student diversity”.

Viewing transfer as a crucial outcome of learning

Still another result of focusing the concept of learning on classrooms is that it raises issues of usefulness or transfer, which is the ability to use knowledge or skill in situations beyond the ones in which they are acquired. Learning to read and learning to solve arithmetic problems, for example, are major goals of the elementary school curriculum because those skills are meant to be used not only inside the classroom, but outside as well. We teachers intend, that is, for reading and arithmetic skills to “transfer”, even though we also do our best to make the skills enjoyable while they are still being learned. In the world inhabited by teachers, even more than in other worlds, making learning fun is certainly a good thing to do, but making learning useful as well as fun is even better. Combining enjoyment and usefulness, in fact, is a “gold standard” of teaching: we generally seek it for students, even though we may not succeed at providing it all of the time.

Major theories and models of learning

Several ideas and priorities, then, affect how we teachers think about learning, including the curriculum, the difference between teaching and learning, sequencing, readiness, and transfer. The ideas form a “screen” through which to understand and evaluate whatever psychology has to offer education. As it turns out, many theories, concepts, and ideas from educational psychology do make it through the “screen” of education, meaning that they are consistent with the professional priorities of teachers and helpful in solving important problems of classroom teaching. In the case of issues about classroom learning, for example, educational psychologists have developed a number of theories and concepts that are relevant to classrooms, in that they describe at least some of what usually happens there and offer guidance for assisting learning. It is helpful to group the theories according to whether they focus on changes in behavior or in thinking. The distinction is rough and inexact, but a good place to begin. For starters, therefore, consider two perspectives about learning, called behaviorism (learning as changes in overt behavior) and constructivism, (learning as changes in thinking). The second category can be further divided into psychological constructivism (changes in thinking resulting from individual experiences), and social constructivism, (changes in thinking due to assistance from others). The rest of this chapter describes key ideas from each of these viewpoints. As I hope you will see, each describes some aspects of learning not just in general, but as it happens in classrooms in particular. So each perspective suggests things that you might do in your classroom to make students’ learning more productive.

Behaviorism: changes in what students do

Behaviorism is a perspective on learning that focuses on changes in individuals’ observable behaviors— changes in what people say or do. At some point we all use this perspective, whether we call it “behaviorism” or something else. The first time that I drove a car, for example, I was concerned primarily with whether I could actually do the driving, not with whether I could describe or explain how to drive. For another example: when I reached the point in life where I began cooking meals for myself, I was more focused on whether I could actually produce edible food in a kitchen than with whether I could explain my recipes and cooking procedures to others. And still another example—one often relevant to new teachers: when I began my first year of teaching, I was more focused on doing the job of teaching—on day-to-day survival—than on pausing to reflect on what I was doing.

Note that in all of these examples, focusing attention on behavior instead of on “thoughts” may have been desirable at that moment, but not necessarily desirable indefinitely or all of the time. Even as a beginner, there are times when it is more important to be able to describe how to drive or to cook than to actually do these things. And there definitely are many times when reflecting on and thinking about teaching can improve teaching itself. (As a teacher-friend once said to me: “Don’t just do something; stand there!”) But neither is focusing on behavior which is not necessarily less desirable than focusing on students’ “inner” changes, such as gains in their knowledge or their personal attitudes. If you are teaching, you will need to attend to all forms of learning in students, whether inner or outward.

In classrooms, behaviorism is most useful for identifying relationships between specific actions by a student and the immediate precursors and consequences of the actions. It is less useful for understanding changes in students’ thinking; for this purpose we need a more cognitive (or thinking-oriented) theory, like the ones described later in this chapter. This fact is not really a criticism of behaviorism as a perspective, but just a clarification of its particular strength or source of usefulness, which is to highlight observable relationships among actions, precursors and consequences. Behaviorists use particular terms (or “lingo”, some might say) for these relationships. They also rely primarily on two basic images or models of behavioral learning, called respondent (or “classical”) conditioning and operant conditioning. The names are derived partly from the major learning mechanisms highlighted by each type, which I describe next.

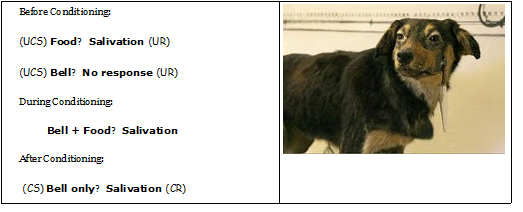

Respondent conditioning: learning new associations with prior behaviors

As originally conceived, respondent conditioning (sometimes also called classical conditioning) begins with the involuntary responses to particular sights, sounds, or other sensations (Lavond, 2003). When I receive an injection from a nurse or doctor, for example, I cringe, tighten my muscles, and even perspire a bit. Whenever a contented, happy baby looks at me, on the other hand, I invariably smile in response. I cannot help myself in either case; both of the responses are automatic. In humans as well as other animals, there is a repertoire or variety of such specific, involuntary behaviors. At the sound of a sudden loud noise, for example, most of us show a “startle” response—we drop what we are doing (sometimes literally!), our heart rate shoots up temporarily, and we look for the source of the sound. Cats, dogs and many other animals (even fish in an aquarium) show similar or equivalent responses.

Involuntary stimuli and responses were first studied systematically early in the twentieth-century by the Russian scientist Ivan Pavlov (1927). Pavlov’s most well-known work did not involve humans, but dogs, and specifically their involuntary tendency to salivate when eating. He attached a small tube to the side of dogs’ mouths that allowed him to measure how much the dogs salivated when fed ( Exhibit 1 shows a photograph of one of Pavlov’s dogs). But he soon noticed a “problem” with the procedure: as the dogs gained experience with the experiment, they often salivated before they began eating. In fact the most experienced dogs sometimes began salivating before they even saw any food, simply when Pavlov himself entered the room! The sight of the experimenter, which had originally been a neutral experience for the dogs, became associated with the dogs’ original salivation response. Eventually, in fact, the dogs would salivate at the sight of Pavlov even if he did not feed them.

This change in the dogs’ involuntary response, and especially its growing independence from the food as stimulus, eventually became the focus of Pavlov’s research. Psychologists named the process respondent conditioning because it describes changes in responses to stimuli (though some have also called it “classical conditioning” because it was historically the first form of behavioral learning to be studied systematically). Respondent conditioning has several elements, each with a special name. To understand these, look at and imagine a dog (perhaps even mine, named Ginger) prior to any conditioning. At the beginning Ginger salivates (an unconditioned response (UR) ) only when she actually tastes her dinner (an unconditioned stimulus (US) ). As time goes by, however, a neutral stimulus—such as the sound of opening a bag containing fresh dog food