Home — Essay Samples — War — Russia and Ukraine War

Essays on Russia and Ukraine War

Writing an essay on the war between Russia and Ukraine is of utmost importance in order to bring awareness to this ongoing conflict and its impact on the global community. This topic is particularly significant as it not only sheds light on the political and military aspects of the war, but also highlights the humanitarian crisis and human rights violations that have arisen as a result.

When writing an essay on this topic, it is crucial to thoroughly research and gather information from reliable sources in order to present a well-informed and balanced perspective. The use of credible sources such as academic journals, news articles, and official reports is essential to ensure the accuracy and reliability of the information presented in the essay.

Additionally, it is important to consider the historical, cultural, and geopolitical context of the war in order to provide a comprehensive analysis. This may involve examining the historical relationship between Russia and Ukraine, the cultural and ethnic dynamics at play, and the broader geopolitical implications of the conflict.

Furthermore, it is essential to approach this topic with sensitivity and empathy, considering the human impact of the war on individuals and communities. This may involve incorporating personal testimonies, humanitarian reports, and accounts of human rights violations in order to provide a human-centric perspective on the conflict.

Overall, writing an essay on the war between Russia and Ukraine is an opportunity to raise awareness and facilitate a deeper understanding of this complex and multifaceted issue. By approaching this topic with diligence, empathy, and a commitment to accuracy, writers can contribute to a more informed and nuanced discourse on this critical global issue.

What Makes a Good Russia and Ukraine War Essay Topics

When it comes to choosing a compelling topic for an essay on the Russia and Ukraine War, it's important to consider a few key factors. First and foremost, the topic should be relevant and timely, addressing current events and ongoing conflicts. Additionally, it's crucial to choose a topic that is both interesting and thought-provoking, allowing for in-depth analysis and critical thinking. To brainstorm and choose the best essay topic, consider the various aspects of the conflict, such as political, social, and economic implications. It's also important to think about the audience and their level of familiarity with the topic, as well as the potential for original research and unique insights. Ultimately, a good essay topic on the Russia and Ukraine War will be one that is impactful, relevant, and intellectually stimulating.

Best Russia and Ukraine War essay topics

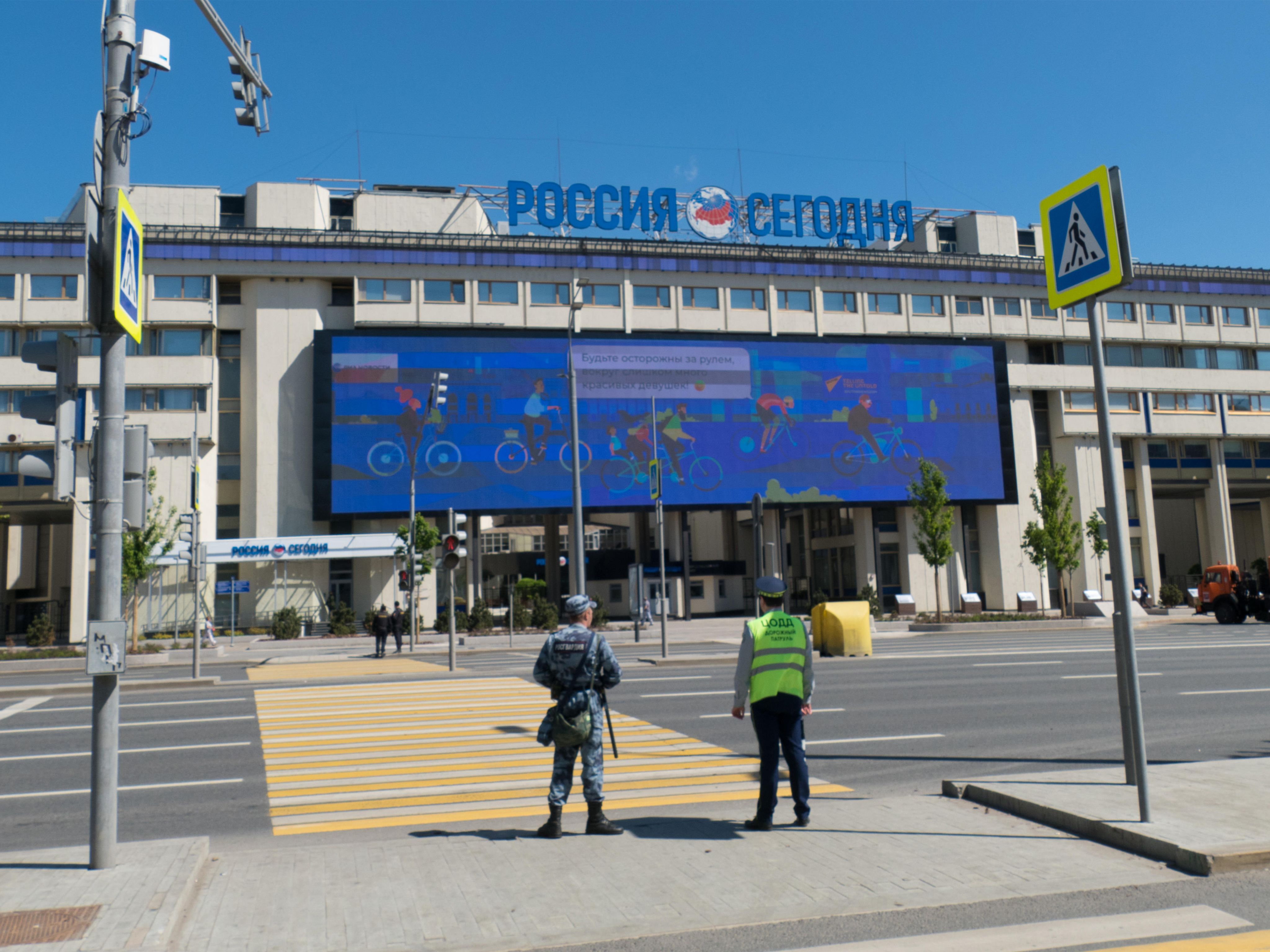

- The role of propaganda in shaping public opinion during the Russia and Ukraine War

- The impact of the conflict on the geopolitical landscape of Eastern Europe

- The humanitarian crisis in Ukraine and its implications for international intervention

- The use of hybrid warfare and unconventional tactics in the Russia and Ukraine War

- The role of energy politics in the conflict between Russia and Ukraine

- The portrayal of the conflict in popular media and its influence on public perception

- The implications of the Russia and Ukraine War on global security and stability

- The historical and cultural roots of the conflict between Russia and Ukraine

- The role of international organizations in mediating the Russia and Ukraine War

- The impact of the conflict on the economy and infrastructure of Ukraine

Russia and Ukraine War essay topics Prompts

- Imagine you are a journalist embedded in a war zone. Describe the challenges and ethical considerations you would face in reporting on the Russia and Ukraine War.

- Write a fictional account of a civilian's experience living in a war-torn region of Ukraine, exploring the psychological and emotional toll of the conflict.

- Create a persuasive argument for or against international military intervention in the Russia and Ukraine War, considering the potential consequences and implications.

- Imagine you are a diplomat tasked with negotiating a ceasefire between Russia and Ukraine. Outline your strategy and approach, considering the competing interests and demands of both parties.

- Write a comparative analysis of the Russia and Ukraine War and another historical conflict, exploring the similarities and differences in terms of tactics, motivations, and outcomes.

Russo-ukrainian War: Unraveling The Complexities of The War in Ukraine

Russia's aggression against ukraine: a historical analysis, made-to-order essay as fast as you need it.

Each essay is customized to cater to your unique preferences

+ experts online

Reflections on Post-war Reconstruction in Ukraine

Russia's invasion of ukraine: un involvement and solutions, russia-ukraine conflict 2014-2024: motives and solutions, is russia's invasion of ukraine - the start of world war, let us write you an essay from scratch.

- 450+ experts on 30 subjects ready to help

- Custom essay delivered in as few as 3 hours

The Impact of Strategic Confrontations in The Russia-ukraine War

How russia's invasion of ukraine caused the wave of protests, the ukraine-poland border amidst conflict, how russia's invasion of ukraine affects the us, get a personalized essay in under 3 hours.

Expert-written essays crafted with your exact needs in mind

Navigating The Intricacies of Ukraine and Poland Relations

Russia's invasion of ukraine: how this destroys south africa, navigating independence: ukraine amidst and post-war, ukraine-russia war: challenges for today and solution for tomorrow, independence post-war: glimpsing into ukraine’s future, leading in war: zelensky’s strategic and humanitarian approaches, the russia-ukraine war: current status and future implications, the russian war in ukraine, exploring the russia-ukraine war: implications, independence day in the shadows of war, the geopolitical context involving nato, ukraine, and russia, post-war challenges and opportunities in ukraine-poland cooperation, united states support for ukrainian independence, the long-term implications of the russia-ukraine war on ukraine-poland relations, relevant topics.

- Vietnam War

- Israeli Palestinian Conflict

- Nuclear Weapon

- Syrian Civil War

- The Spanish American War

- Atomic Bomb

- Cruise Missile

- Nuclear War

By clicking “Check Writers’ Offers”, you agree to our terms of service and privacy policy . We’ll occasionally send you promo and account related email

No need to pay just yet!

We use cookies to personalyze your web-site experience. By continuing we’ll assume you board with our cookie policy .

- Instructions Followed To The Letter

- Deadlines Met At Every Stage

- Unique And Plagiarism Free

9 big questions about Russia’s war in Ukraine, answered

Addressing some of the most pressing questions of the whole war, from how it started to how it might end.

If you buy something from a Vox link, Vox Media may earn a commission. See our ethics statement.

by Zack Beauchamp

The Russian war in Ukraine has proven itself to be one of the most consequential political events of our time — and one of the most confusing.

From the outset, Russia’s decision to invade was hard to understand; it seemed at odds with what most experts saw as Russia’s strategic interests. As the war has progressed, the widely predicted Russian victory has failed to emerge as Ukrainian fighters have repeatedly fended off attacks from a vastly superior force. Around the world, from Washington to Berlin to Beijing, global powers have reacted in striking and even historically unprecedented fashion.

What follows is an attempt to make sense of all of this: to tackle the biggest questions everyone is asking about the war. It is a comprehensive guide to understanding what is happening in Ukraine and why it matters.

1) Why did Russia invade Ukraine?

In a televised speech announcing Russia’s “special military operation” in Ukraine on February 24 , Russian President Vladimir Putin said the invasion was designed to stop a “genocide” perpetrated by “the Kyiv regime” — and ultimately to achieve “the demilitarization and de-Nazification of Ukraine.”

Though the claims of genocide and Nazi rule in Kyiv were transparently false , the rhetoric revealed Putin’s maximalist war aims: regime change (“de-Nazification”) and the elimination of Ukraine’s status as a sovereign state outside of Russian control (“demilitarization”). Why he would want to do this is a more complex story, one that emerges out of the very long arc of Russian-Ukrainian relations.

Ukraine and Russia have significant, deep, and longstanding cultural and historical ties; both date their political origins back to the ninth-century Slavic kingdom of Kievan Rus. But these ties do not make them historically identical, as Putin has repeatedly claimed in his public rhetoric. Since the rise of the modern Ukrainian national movement in the mid- to late-19th century , Russian rule in Ukraine — in both the czarist and Soviet periods — increasingly came to resemble that of an imperial power governing an unwilling colony .

Russian imperial rule ended in 1991 when 92 percent of Ukrainians voted in a national referendum to secede from the decaying Soviet Union. Almost immediately afterward , political scientists and regional experts began warning that the Russian-Ukrainian border would be a flashpoint, predicting that internal divides between the more pro-European population of western Ukraine and relatively more pro-Russian east , contested territory like the Crimean Peninsula , and Russian desire to reestablish control over its wayward vassal could all lead to conflict between the new neighbors.

It took about 20 years for these predictions to be proven right. In late 2013, Ukrainians took tothe streets to protest the authoritarian and pro-Russian tilt of incumbent President Viktor Yanukovych, forcing his resignation on February 22, 2014. Five days later, the Russian military swiftly seized control of Crimea and declared it Russian territory, a brazenly illegal move that a majority of Crimeans nonetheless seemed to welcome . Pro-Russia protests in Russian-speaking eastern Ukraine gave way to a violent rebellion — one stoked and armed by the Kremlin , and backed by disguised Russian troops .

The Ukrainian uprising against Yanukovych — called the “Euromaidan” movement because they were pro-EU protests that most prominently took place in Kyiv’s Maidan square — represented to Russia a threat not just to its influence over Ukraine but to the very survival of Putin’s regime. In Putin’s mind, Euromaidan was a Western-sponsored plot to overthrow a Kremlin ally, part of a broader plan to undermine Russia itself that included NATO’s post-Cold War expansions to the east.

“We understand what is happening; we understand that [the protests] were aimed against Ukraine and Russia and against Eurasian integration,” he said in a March 2014 speech on the annexation of Crimea. “With Ukraine, our Western partners have crossed the line.”

Beneath this rhetoric, according to experts on Russia, lies a deeper unstated fear: that his regime might fall prey to a similar protest movement . Ukraine could not succeed, in his view, because it might create a pro-Western model for Russians to emulate — one that the United States might eventually try to covertly export to Moscow. This was a central part of his thinking in 2014 , and it remains sotoday.

“He sees CIA agents behind every anti-Russian political movement,” says Seva Gunitsky, a political scientist who studies Russia at the University of Toronto. “He thinks the West wants to subvert his regime the way they did in Ukraine.”

Beginning in March 2021, Russian forces began deploying to the Ukrainian border in larger and larger numbers. Putin’s nationalist rhetoric became more aggressive: In July 2021, the Russian president published a 5,000-word essay arguing that Ukrainian nationalism was a fiction, that the country was historically always part of Russia, and that a pro-Western Ukraine posed an existential threat to the Russian nation.

- Europe’s embrace of Ukrainian refugees, explained in six charts and one map

“The formation of an ethnically pure Ukrainian state, aggressive towards Russia, is comparable in its consequences to the use of weapons of mass destruction against us,” as he put it in his 2021 essay .

Why Putin decided that merely seizing part of Ukraine was no longer enough remains a matter of significant debate among experts. One theory, advanced by Russian journalist Mikhail Zygar , is that pandemic-induced isolation drove him to an extreme ideological place.

But while the immediate cause of Putin’s shift on Ukraine is not clear, the nature of that shift is. His longtime belief in the urgency of restoring Russia’s greatness curdled into a neo-imperial desire to bring Ukraine back under direct Russian control. And in Russia, where Putin rules basically unchecked, that meant a full-scale war.

2) Who is winning the war?

On paper , Russia’s military vastly outstrips Ukraine’s. Russia spends over 10 times as much on defense annually as Ukraine; the Russian military has a little under three times as much artillery as Ukraine and roughly 10 times as many fixed-wing aircraft. As a result, the general pre-invasion view was that Russia would easily win a conventional war. In early February, Chairman of the Joint Chiefs Mark Milley told members of Congress that Kyiv, the capital, could fall within 72 hours of a Russian invasion .

But that’s not how things have played out . A month into the invasion, Ukrainians still hold Kyiv. Russia has made some gains, especially in the east and south, but the consensus view among military experts is that Ukraine’s defenses have held stoutly — to the point where Ukrainians have been able to launch counteroffensives .

The initial Russian plan reportedly operated under the assumption that a swift march on Kyiv would meet only token resistance. Putin “actually really thought this would be a ‘special military operation’: They would be done in a few days, and it wouldn’t be a real war,” says Michael Kofman, an expert on the Russian military at the CNA think tank.

This plan fell apart within the first 48 hours of the war when early operations like an airborne assault on the Hostomel airport ended in disaster , forcing Russian generals to develop a new strategy on the fly. What they came up with — massive artillery bombardments and attempts to encircle and besiege Ukraine’s major cities — was more effective (and more brutal). The Russians made some inroads into Ukrainian territory, especially in the south, where they have laid siege to Mariupol and taken Kherson and Melitopol.

But these Russian advances are a bit misleading. Ukraine, Kofman explains, made the tactical decision to trade “space for time” : to withdraw strategically rather than fight for every inch of Ukrainian land, confronting the Russians on the territory and at the time of their choosing.

As the fighting continued, the nature of the Ukrainian choice became clearer. Instead of getting into pitched large-scale battles with Russians on open terrain, where Russia’s numerical advantages would prove decisive, the Ukrainians instead decided to engage in a series of smaller-scale clashes .

Ukrainian forces have bogged down Russian units in towns and smaller cities ; street-to-street combat favors defenders who can use their superior knowledge of the city’s geography to hide and conduct ambushes. They have attacked isolated and exposed Russian units traveling on open roads. They have repeatedly raided poorly protected supply lines.

This approach has proven remarkably effective. By mid-March, Western intelligence agencies and open source analysts concluded that the Ukrainians had successfully managed to stall the Russian invasion. The Russian military all but openly recognized this reality in a late March briefing, in which top generals implausibly claimed they never intended to take Kyiv and were always focused on making territorial gains in the east.

“The initial Russian campaign to invade and conquer Ukraine is culminating without achieving its objectives — it is being defeated, in other words,” military scholar Frederick Kagan wrote in a March 22 brief for the Institute for the Study of War (ISW) think tank.

Currently, Ukrainian forces are on the offensive. They have pushed the Russians farther from Kyiv , with some reports suggesting they have retaken the suburb of Irpin and forced Russia to withdraw some of its forces from the area in a tacit admission of defeat. In the south, Ukrainian forces are contesting Russian control over Kherson .

And throughout the fighting, Russian casualties have been horrifically high.

It’s hard to get accurate information in a war zone, but one of the more authoritative estimates of Russian war dead — from the US Defense Department — concludes that over 7,000 Russian soldiers have been killed in the first three weeks of fighting, a figure about three times as large as the total US service members dead in all 20 years of fighting in Afghanistan. A separate NATO estimate puts that at the low end, estimating between 7,000 and 15,000 Russians killed in action and as many as 40,000 total losses (including injuries, captures, and desertions). Seven Russian generals have been reported killed in the fighting, and materiel losses — ranging from armor to aircraft — have been enormous. (Russia puts its death toll at more than 1,300 soldiers, which is almost certainly a significant undercount.)

This all does not mean that a Russian victory is impossible. Any number of things, ranging from Russian reinforcements to the fall of besieged Mariupol, could give the war effort new life.

It does, however, mean that what Russia is doing right now hasn’t worked.

“If the point is just to wreak havoc, then they’re doing fine. But if the point is to wreak havoc and thus advance further — be able to hold more territory — they’re not doing fine,” says Olga Oliker, the program director for Europe and Central Asia at the International Crisis Group.

3) Why is Russia’s military performing so poorly?

Russia’s invasion has gone awry for two basic reasons: Its military wasn’t ready to fight a war like this, and the Ukrainians have put up a much stronger defense than anyone expected.

Russia’s problems begin with Putin’s unrealistic invasion plan. But even after the Russian high command adjusted its strategy, other flaws in the army remained.

“We’re seeing a country militarily implode,” says Robert Farley, a professor who studies air power at the University of Kentucky.

One of the biggest and most noticeable issues has been rickety logistics. Some of the most famous images of the war have been of Russian armored vehicles parked on Ukrainian roads, seemingly out of gas and unable to advance. The Russian forces have proven to be underequipped and badly supplied, encountering problems ranging from poor communications to inadequate tires .

Part of the reason is a lack of sufficient preparation. Per Kofman, the Russian military simply “wasn’t organized for this kind of war” — meaning, the conquest of Europe’s second-largest country by area. Another part of it is corruption in the Russian procurement system. Graft in Russia is less a bug in its political system than a feature; one way the Kremlin maintains the loyalty of its elite is by allowing them to profit off of government activity . Military procurement is no exception to this pattern of widespread corruption, and it has led to troops having substandard access to vital supplies .

The same lack of preparation has plagued Russia’s air force . Despite outnumbering the Ukrainian air force by roughly 10 times, the Russians have failed to establish air superiority: Ukraine’s planes are still flying and its air defenses mostly remain in place .

“The Russian Army was not prepared to fight this war” —Jason Lyall, Dartmouth political scientist

Perhaps most importantly, close observers of the war believe Russians are suffering from poor morale. Because Putin’s plan to invade Ukraine was kept secret from the vast majority of Russians, the government had a limited ability to lay a propaganda groundwork that would get their soldiers motivated to fight. The current Russian force has little sense of what they’re fighting for or why — and are waging war against a country with which they have religious, ethnic, historical, and potentially even familial ties. In a military that has long had systemic morale problems, that’s a recipe for battlefield disaster.

“Russian morale was incredibly low BEFORE the war broke out. Brutal hazing in the military, second-class (or worse) status by its conscript soldiers, ethnic divisions, corruption, you name it: the Russian Army was not prepared to fight this war,” Jason Lyall, a Dartmouth political scientist who studies morale, explains via email. “High rates of abandoned or captured equipment, reports of sabotaged equipment, and large numbers of soldiers deserting (or simply camping out in the forest) are all products of low morale.”

The contrast with the Ukrainians couldn’t be starker. They are defending their homes and their families from an unprovoked invasion, led by a charismatic leader who has made a personal stand in Kyiv. Ukrainian high moraleis a key reason, in addition to advanced Western armaments, that the defenders have dramatically outperformed expectations.

“Having spent a chunk of my professional career [working] with the Ukrainians, nobody, myself included and themselves included, had all that high an estimation of their military capacity,” Oliker says.

Again, none of this will necessarily remain the case throughout the war. Morale can shift with battlefield developments. And even if Russian morale remains low, it’s still possible for them to win — though they’re more likely to do so in a brutally ugly fashion.

4) What has the war meant for ordinary Ukrainians?

As the fighting has dragged on, Russia has gravitated toward tactics that, by design, hurt civilians. Most notably, Russia has attempted to lay siege to Ukraine’s cities, cutting off supply and escape routes while bombarding them with artillery. The purpose of the strategy is to wear down the Ukrainian defenders’ willingness to fight, including by inflicting mass pain on the civilian populations.

The result has been nightmarish: an astonishing outflow of Ukrainian refugees and tremendous suffering for many of those who were unwilling or unable to leave.

According to the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees , more than 3.8 million Ukrainians fled the country between February 24 and March 27. That’s about 8.8 percent of Ukraine’s total population — in proportional terms, the rough equivalent of the entire population of Texas being forced to flee the United States.

Another point of comparison: In 2015, four years into the Syrian civil war and the height of the global refugee crisis, there were a little more than 4 million Syrian refugees living in nearby countries . The Ukraine war has produced a similarly sized exodus in just a month, leading to truly massive refugee flows to its European neighbors. Poland, the primary destination of Ukrainian refugees, is currently housing over 2.3 million Ukrainians, a figure larger than the entire population of Warsaw, its capital and largest city.

For those civilians who have been unable to flee, the situation is dire. There are no reliable estimates of death totals; a March 27 UN estimate puts the figure at 1,119 but cautions that “the actual figures are considerably higher [because] the receipt of information from some locations where intense hostilities have been going on has been delayed and many reports are still pending corroboration.”

The UN assessment does not blame one side or the other for these deaths, but does note that “most of the civilian casualties recorded were caused by the use of explosive weapons with a wide impact area, including shelling from heavy artillery and multiple-launch rocket systems, and missile and airstrikes.” It is the Russians, primarily, who are using these sorts of weapons in populated areas; Human Rights Watch has announced that there are “early signs of war crimes” being committed by Russian soldiers in these kinds of attacks, and President Joe Biden has personally labeled Putin a “war criminal.”

Nowhere is this devastation more visible than the southern city of Mariupol, the largest Ukrainian population center to which Russia has laid siege. Aerial footage of the city published by the Guardian in late March reveals entire blocks demolished by Russian bombardment:

In mid-March, three Associated Press journalists — the last international reporters in the city before they too were evacuated — managed to file a dispatch describing life on the ground. They reported a death total of 2,500 but cautioned that “many bodies can’t be counted because of the endless shelling .” The situation is impossibly dire:

Airstrikes and shells have hit the maternity hospital, the fire department, homes, a church, a field outside a school. For the estimated hundreds of thousands who remain, there is quite simply nowhere to go. The surrounding roads are mined and the port blocked. Food is running out, and the Russians have stopped humanitarian attempts to bring it in. Electricity is mostly gone and water is sparse, with residents melting snow to drink. Some parents have even left their newborns at the hospital, perhaps hoping to give them a chance at life in the one place with decent electricity and water.

The battlefield failures of the Russian military have raised questions about its competence in difficult block-to-block fighting; Farley, the Kentucky professor, says, “This Russian army does not look like it can conduct serious [urban warfare].” As a result, taking Ukrainian cities means besieging them — starving them out, destroying their will to fight, and only moving into the city proper after its population is unwilling to resist or outright incapable of putting up a fight.

5) What do Russians think about the war?

Vladimir Putin’s government has ramped up its already repressive policies during the Ukraine conflict, shuttering independent media outlets and blocking access to Twitter, Facebook, and Instagram . It’s now extremely difficult to get a sense of what either ordinary Russians or the country’s elite think about the war, as criticizing it could lead to a lengthy stint in prison.

But despite this opacity, expert Russia watchers have developed a broad idea of what’s going on there. The war has stirred up some opposition and anti-Putin sentiment, but it has been confined to a minority who are unlikely to change Putin’s mind, let alone topple him.

The bulk of the Russian public was no more prepared for war than the bulk of the Russian military — in fact, probably less so. After Putin announced the launch of his “special military operation” in Ukraine on national television, there was a surprising amount of criticism from high-profile Russians — figures ranging from billionaires to athletes to social media influencers. One Russian journalist, Marina Ovsyannikova, bravely ran into the background of a government broadcast while holding an antiwar sign.

“It is unprecedented to see oligarchs, other elected officials, and other powerful people in society publicly speaking out against the war,” says Alexis Lerner, a scholar of dissent in Russia at the US Naval Academy.

There have also been antiwar rallies in dozens of Russian cities. How many have participated in these rallies is hard to say, but the human rights group OVD-Info estimates that over 15,000 Russians have been arrested at the events since the war began.

Could these eruptions ofantiwar sentiment at the elite and mass public level suggesta comingcoup or revolution against the Putin regime? Experts caution that these events remain quite unlikely.

Putin has done an effective job engaging in what political scientists call “coup-proofing.” He has put in barriers — from seeding the military with counterintelligence officers to splitting up the state security services into different groups led by trusted allies — that make it quite difficult for anyone in his government to successfully move against him.

“Putin has prepared for this eventuality for a long time and has taken a lot of concerted actions to make sure he’s not vulnerable,” says Adam Casey, a postdoctoral fellow at the University of Michigan who studies the history of coups in Russia and the former communist bloc.

Similarly, turning the antiwar protests into a full-blown influential movement is a very tall order.

“It is hard to organize sustained collective protest in Russia,” notes Erica Chenoweth, a political scientist at Harvard who studies protest movements . “Putin’s government has criminalized many forms of protests, and has shut down or restricted the activities of groups, movements, and media outlets perceived to be in opposition or associated with the West.”

Underpinning it all is tight government control of the information environment. Most Russians get their news from government-run media , which has been serving up a steady diet of pro-war content. Many of them appear to genuinely believe what they hear: One independent opinion poll found that 58 percent of Russians supported the war to at least some degree.

Prior to the war, Putin also appeared to be a genuinely popular figure in Russia. The elite depend on him for their position and fortune; many citizens see him as the man who saved Russia from the chaos of the immediate post-Communist period. A disastrous war might end up changing that, but the odds that even a sustained drop in his support translates into a coup or revolution remain low indeed.

6) What is the US role in the conflict?

The war remains, for the moment, a conflict between Ukraine and Russia. But the United States is the most important third party, using a number of powerful tools — short of direct military intervention — to aid the Ukrainian cause.

Any serious assessment of US involvement needs to start in the post-Cold War 1990s , when the US and its NATO allies made the decision to open alliance membership to former communist states.

Many of these countries, wary of once again being put under the Russian boot, clamored to join the alliance, which commits all involved countries to defend any member-state in the event of an attack. In 2008, NATO officially announced that Georgia and Ukraine — two former Soviet republics right on Russia’s doorstep — “ will become members of NATO ” at an unspecified future date. This infuriated the Russians, who saw NATO expansion as a direct threat to their own security.

There is no doubt that NATO expansion helped create some of the background conditions under which the current conflict became thinkable, generally pushing Putin’s foreign policy in a more anti-Western direction. Some experts see it as one of the key causes of his decision to attack Ukraine — but others strongly disagree, noting that NATO membership for Ukraine was already basically off the table before the war and that Russia’s declared war aims went far beyond simply blocking Ukraine’s NATO bid .

“NATO expansion was deeply unpopular in Russia. [But] Putin did not invade because of NATO expansion,” says Yoshiko Herrera, a Russia expert at the University of Wisconsin-Madison.

Regardless of where one falls on that debate, US policy during the conflict has been exceptionally clear: support the Ukrainians with massive amounts of military assistance while putting pressure on Putin to back down by organizing an unprecedented array of international economic sanctions.

On the military side, weapons systems manufactured and provided by the US and Europe have played a vital role in blunting Russia’s advance. The Javelin anti-tank missile system, for example, is a lightweight American-made launcher that allows one or two infantry soldiers to take out a tank . Javelins have given the outgunned Ukrainians a fighting chance against Russian armor, becoming a popular symbol in the process .

Sanctions have proven similarly devastating in the economic realm .

The international punishments have been extremely broad, ranging from removing key Russian banks from the SWIFT global transaction system to a US ban on Russian oil imports to restrictions on doing business with particular members of the Russian elite . Freezing the assets of Russia’s central bank has proven to be a particularly damaging tool, wrecking Russia’s ability to deal with the collapse in the value of the ruble, its currency. As a result, the Russian economy is projected to contract by 15 percent this year ; mass unemployment looms .

There is more America can do, particularly when it comes to fulfilling Ukrainian requests for new fighter jets. In March, Washington rejected a Polish plan to transfer MiG-29 aircraft to Ukraine via a US Air Force base in Germany, arguing that it could be too provocative.

But the MiG-29 incident is more the exception than it is the rule. On the whole, the United States has been strikingly willing to take aggressive steps to punish Moscow and aid Kyiv’s war effort.

7) How is the rest of the world responding to Russia’s actions?

On the surface, the world appears to be fairly united behind the Ukrainian cause. The UN General Assembly passed a resolution condemning the Russian invasion by a whopping 141-5 margin (with 35 abstentions). But the UN vote conceals a great deal of disagreement, especially among the world’s largest and most influential countries — divergences that don’t always fall neatly along democracy-versus-autocracy lines.

The most aggressive anti-Russian and pro-Ukrainian positions can, perhaps unsurprisingly, be found in Europe and the broader West. EU and NATO members, with the partial exceptions of Hungary and Turkey , have strongly supported the Ukrainian war effort and implemented punishing sanctions on Russia (a major trading partner). It’s the strongest show of European unity since the Cold War, one that many observers see as a sign that Putin’s invasion has already backfired.

Germany, which has important trade ties with Russia and a post-World War II tradition of pacifism, is perhaps the most striking case. Nearly overnight, the Russian invasion convinced center-left Chancellor Olaf Scholz to support rearmament , introducing a proposal to more than triple Germany’s defense budget that’s widely backed by the German public.

“It’s really revolutionary,” Sophia Besch, a Berlin-based senior research fellow at the Centre for European Reform, told my colleague Jen Kirby . “Scholz, in his speech, did away with and overturned so many of what we thought were certainties of German defense policy.”

Though Scholz has refused to outright ban Russian oil and gas imports, he has blocked the Nord Stream 2 gas pipeline and committed to a long-term strategy of weaning Germany off of Russian energy. All signs point to Russia waking a sleeping giant — of creating a powerful military and economic enemy in the heart of the European continent.

China, by contrast, has been the most pro-Russia of the major global powers.

The two countries, bound by shared animus toward a US-dominated world order, have grown increasingly close in recent years. Chinese propaganda has largely toed the Russian line on the Ukraine war. US intelligence, which has been remarkably accurate during the crisis, believes that Russia has requested military and financial assistance from Beijing — which hasn’t been provided yet but may well be forthcoming.

That said, it’s possible to overstate the degree to which China has taken the Russian side. Beijing has a strong stated commitment to state sovereignty — the bedrock of its position on Taiwan is that the island is actually Chinese territory — which makes a full-throated backing of the invasion ideologically awkward . There’s a notable amount of debate among Chinese policy experts and in the public , with some analysts publicly advocating that Beijing adopt a more neutral line on the conflict.

Most other countries around the world fall somewhere on the spectrum between the West and China. Outside of Europe, only a handful of mostly pro-American states — like South Korea, Japan, and Australia — have joined the sanctions regime. The majority of countries in Asia, the Middle East, Africa, and Latin America do not support the invasion, but won’t do very much to punish Russia for it either.

- Why India isn’t denouncing Russia’s Ukraine war

India is perhaps the most interesting country in this category. A rising Asian democracy that has violently clashed with China in the very recent past , it has good reasons to present itself as an American partner in the defense of freedom. Yet India also depends heavily on Russian-made weapons for its own defense and hopes to use its relationship with Russia to limit the Moscow-Beijing partnership. It’s also worth noting that India’s prime minister, Narendra Modi, has strong autocratic inclinations .

The result of all of this is a balancing act reminiscent of India’s Cold War approach of “non-alignment” : refusing to side with either the Russian or American positions while attempting to maintain decent relations with both . India’s perceptions of its strategic interests, more than ideological views about democracy, appear to be shaping its response to the war — as seems to be the case with quite a few countries around the world.

8) Could this turn into World War III?

The basic, scary answer to this question is yes: The invasion of Ukraine has put us at the greatest risk of a NATO-Russia war in decades.

The somewhat more comforting and nuanced answer is that the absolute risk remains relatively low so long as there is no direct NATO involvement in the conflict, which the Biden administration has repeatedly ruled out . Though Biden said “this man [Putin] cannot remain in power” in a late March speech, both White House officials and the president himself stressed afterward that the US policy was not regime change in Moscow.

“Things are stable in a nuclear sense right now,” says Jeffrey Lewis, an expert on nuclear weapons at the Middlebury Institute of International Studies. “The minute NATO gets involved, the scope of the war widens.”

In theory, US and NATO military assistance to Ukraine could open the door to escalation: Russia could attack a military depot in Poland containing weapons bound for Ukraine, for instance. But in practice, it’s unlikely: The Russians don’t appear to want a wider war with NATO that risks nuclear escalation, and so have avoided cross-border strikes even when it might destroy supply shipments bound for Ukraine.

In early March, the US Department of Defense opened a direct line of communication with its Russian peers in order to avoid any kind of accidental conflict. It’s not clear how well this is working — some reporting suggests the Russians aren’t answering American calls — but there is a long history of effective dialogue between rivals who are fighting each other through proxy forces.

“States often cooperate to keep limits on their wars even as they fight one another clandestinely,” Lyall, the Dartmouth professor, tells me. “While there’s always a risk of unintended escalation, historical examples like Vietnam, Afghanistan (1980s), Afghanistan again (post-2001), and Syria show that wars can be fought ‘within bounds.’”

If the United States and NATO heed the call of Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelenskyy to impose a so-called “no-fly zone” over Ukrainian skies, the situation changes dramatically. No-fly zones are commitments to patrol and, if necessary, shoot down military aircraft that fly in the declared area, generally for the purpose of protecting civilians. In Ukraine, that would mean the US and its NATO allies sending in jets to patrol Ukraine’s skies — and being willing to shoot down any Russian planes that enter protected airspace. From there, the risks of a nuclear conflict become terrifyingly high.

Russia recognizes its inferiority to NATO in conventional terms; its military doctrine has long envisioned the use of nuclear weapons in a war with the Western alliance . In his speech declaring war on Ukraine, Putin all but openly vowed that any international intervention in the conflict would trigger nuclear retaliation.

“To anyone who would consider interfering from the outside: If you do, you will face consequences greater than any you have faced in history,” the Russian president said. “I hope you hear me.”

The Biden administration is taking these threats seriously. Much as the Kremlin hasn’t struck NATO supply missions to Ukraine, the White House has flatly rejected a no-fly zone or any other kind of direct military intervention.

“We will not fight a war against Russia in Ukraine,” Biden said on March 11 . “Direct conflict between NATO and Russia is World War III, something we must strive to prevent.”

This does not mean the risk of a wider war is zero . Accidents happen, and countries can be dragged into war against their leaders’ best judgment. Political positions and risk calculi can also change: If Russia starts losing badly and uses smaller nukes on Ukrainian forces (called “tactical” nuclear weapons), Biden would likely feel the need to respond in some fairly aggressive way. Much depends on Washington and Moscow continuing to show a certain level of restraint.

9) How could the war end?

Wars do not typically end with the total defeat of one side or the other. More commonly, there’s some kind of negotiated settlement — either a ceasefire or more permanent peace treaty — where the two sides agree to stop fighting under a set of mutually agreeable terms.

It is possible that the Ukraine conflict turns out to be an exception: that Russian morale collapses completely, leading to utter battlefield defeat, or that Russia inflicts so much pain that Kyiv collapses. But most analysts believe that neither of these is especially likely given the way the war has played out to date.

“No matter how much military firepower they pour into it, [the Russians] are not going to be able to achieve regime change or some of their maximalist aims,” Kofman, of the CNA think tank, declares.

A negotiated settlement is the most likely way the conflict ends. Peace negotiations between the two sides are ongoing, and some reporting suggests they’re bearing fruit. On March 28, the Financial Times reported significant progress on a draft agreement covering issues ranging from Ukrainian NATO membership to the “de-Nazification” of Ukraine. The next day, Russia pledged to decrease its use of force in Ukraine’s north as a sign of its commitment to the talks.

American officials, though, have been publicly skeptical of Russia’s seriousness in the talks. Even if Moscow is committed to reaching a settlement, the devil is always in the details with these sorts of things — and there are lots of barriers standing in the way of a successful resolution.

Take NATO. The Russians want a simple pledge that Ukraine will remain “neutral” — staying out of foreign security blocs. The current draft agreement, per the Financial Times, does preclude Ukrainian NATO membership, but it permits Ukraine to join the EU. It also commits at least 11 countries, including the United States and China, to coming to Ukraine’s aid if it is attacked again. This would put Ukraine on a far stronger security footing than it had before the war — a victory for Kyiv and defeat for Moscow, one that Putin may ultimately conclude is unacceptable.

- What, exactly, is a “neutral” Ukraine?

Another thorny issue — perhaps the thorniest — is the status of Crimea and the two breakaway Russian-supported republics in eastern Ukraine. The Russians want Ukrainian recognition of its annexation of Crimea and the independence of the Donetsk and Luhansk regions; Ukraine claims all three as part of its territory. Some compromise is imaginable here — an internationally monitored referendum in each territory, perhaps — but what that would look like is not obvious.

The resolution of these issues will likely depend quite a bit on the war’s progress. The more each side believes it has a decent chance to improve its battlefield position and gain leverage in negotiations, the less reason either will have to make concessions to the other in the name of ending the fighting.

And even if they do somehow come to an agreement, it may not end up holding .

On the Ukrainian side, ultra-nationalist militias could work to undermine any agreement with Russia that they believe gives away too much, as they threatened during pre-war negotiations aimed at preventing the Russian invasion .

On the Russian side, an agreement is only as good as Putin’s word. Even if it contains rigorous provisions designed to raise the costs of future aggression, like international peacekeepers, that may not hold him back from breaking the agreement.

This invasion did, after all, start with him launching an invasion that seemed bound to hurt Russia in the long run. Putin dragged the world into this mess; when and how it gets out of it depends just as heavily on his decisions.

More in this stream

Ukraine is finally getting more US aid. It won’t win the war — but it can save them from defeat.

There are now more land mines in Ukraine than almost anywhere else on the planet

A harrowing film exposes the brutality of Russia’s war in Ukraine

Most popular, the supreme court just lit a match and tossed it into dozens of federal agencies, can democrats replace biden as their nominee, democrats can and should replace joe biden, the supreme court hands an embarrassing defeat to america’s trumpiest court, the silver lining to biden’s debate disaster, today, explained.

Understand the world with a daily explainer plus the most compelling stories of the day.

More in Explainers

Is Nvidia stock overvalued? It depends on the future of AI.

Julian Assange’s release is still a lose-lose for press freedom

What two years without Roe looks like, in 8 charts

Mysterious monoliths are appearing across the world. Here’s what we know.

What to know about Biden’s new plan to legalize US citizens’ undocumented family members

House of the Dragon and the Targaryen family, explained

How Democrats got here

Why the Supreme Court just ruled in favor of over 300 January 6 insurrectionists

What about Kamala?

The Supreme Court just made a massive power grab it will come to regret

The Democrats who could replace Biden if he steps aside

Hawk Tuah Girl, explained by straight dudes

PUBLICATIONS

Through its publications, INSS aims to provide expert insights, cutting-edge research, and innovative solutions that contribute to shaping the national security discourse and preparing the next generation of leaders in the field.

Publications

Russia's war in ukraine: identity, history, and conflict.

By Jeffrey Mankoff CSIS

Russia’s invasion of Ukraine constitutes the biggest threat to peace and security in Europe since the end of the Cold War. On February 21, 2022, Russian president Vladimir Putin gave a bizarre and at times unhinged speech laying out a long list of grievances as justification for the “special military operation” announced the following day. While these grievances included the long-simmering dispute over the expansion of the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) and the shape of the post–Cold War security architecture in Europe, the speech centered on a much more fundamental issue: the legitimacy of Ukrainian identity and statehood themselves. It reflected a worldview Putin had long expressed, emphasizing the deep-seated unity among the Eastern Slavs—Russians, Ukrainians, and Belarusians, who all trace their origins to the medieval Kyivan Rus commonwealth—and suggesting that the modern states of Russia, Ukraine, and Belarus should share a political destiny both today and in the future. The corollary to that view is the claim that distinct Ukrainian and Belarusian identities are the product of foreign manipulation and that, today, the West is following in the footsteps of Russia’s imperial rivals in using Ukraine (and Belarus) as part of an “ anti-Russia project .”

Throughout Putin’s time in office, Moscow has pursued a policy toward Ukraine and Belarus predicated on the assumption that their respective national identities are artificial—and therefore fragile. Putin’s arguments about foreign enemies promoting Ukrainian (and, in a more diffuse way, Belarusian) identity as part of a geopolitical struggle against Russia echo the way many of his predecessors refused to accept the agency of ordinary people seeking autonomy from tsarist or Soviet domination. The historically minded Putin often invokes the ideas of thinkers emphasizing the organic unity of the Russian Empire and its people—especially its Slavic, Orthodox core—in a form of what the historian Timothy Snyder calls the “politics of eternity,” the belief in an unchanging historical essence.

The salience that Putin and other Russian elites assign to the idea of Russian-Ukrainian-Belarusian unity helps explain the origins of the current conflict, notably why Moscow was willing to risk a large-scale war on its borders when neither Ukraine nor NATO posed any military threat. It also suggests that Moscow’s ambitions extend beyond preventing Ukrainian NATO membership and encompass a more thorough aspiration to dominate Ukraine politically, militarily, and economically.

Read the rest of the report at CSIS -

Jeffrey Mankoff is a Distinguished Research Fellow at the Institute for National Strategic Studies, Center for Strategic Research at National Defense University.

The views expressed are the authors own and do not reflect those of the National Defense University, the Department of Defense, or the U.S. Government.

- Skip to primary navigation

- Skip to main content

- Skip to primary sidebar

UPSC Coaching, Study Materials, and Mock Exams

Enroll in ClearIAS UPSC Coaching Join Now Log In

Call us: +91-9605741000

Russia-Ukraine Conflict

Last updated on December 29, 2023 by ClearIAS Team

Russia amassed a large number of troops near the Russia-Ukraine border sparking apprehensions on an impending war between the two countries and possible annexation of Ukraine.

Table of Contents

What led to the Russia-Ukraine Conflict?

In December 2021, Russia published an 8-point draft security agreement for the West. The draft was aimed at resolving tensions in Europe including the Ukrainian crisis.

But it had controversial provisions including banning Ukraine from joining the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) , curtailing the further expansion of NATO, blocking drills in the region, etc.

Talks on the draft failed continuously and tensions escalated with the Russian troop buildup in the Russia-Ukraine border.

The crisis has grabbed global headlines and has been dubbed to be capable of triggering a new “cold war” or even a “third world war”.

History of Russia-Ukraine relations

Your Favourite Programs to Clear UPSC CSE: Download Timetable and Study Plan ⇓

(1) ⇒ UPSC Mains Test Series 2024

(2) ⇒ UPSC Prelims Test Series 2025

(3) ⇒ UPSC Fight Back 2025

(4) ⇒ UPSC Prelims cum Mains 2025

With over 6 lakh sq. km area and more than 40 million populations, Ukraine is the second-largest country by area and the 8 th populous in Europe.

Ukraine is bordered by Russia in the East, Belarus in the North, Poland, Slovakia, Hungary, Romania, and Moldova in the West. It also has a maritime boundary with the Black Sea and the Sea of Azov.

Ukraine was under different rulers including the Ottoman Empire, Russian Empire, and the Soviet Union.

It gained independence in 1991 following the disintegration of the Soviet Union.

Orange Revolution of 2004-05

Following the 2004 Presidential election in Ukraine, a series of protests and civil unrest occurred in the country, dubbed the Orange Revolution.

The corruption and malpractice charges in voting alleged by the protestors were upheld by the Supreme Court and the court annulled the election results. Viktor Yushchenko was declared the winner following the re-election. His campaign colour theme was orange, hence the name.

Euromaidan movement

In 2014, the country grabbed attention for the Euromaidan movement or the Revolution of dignity. The civil unrests were based on goals including the removal of then-President Viktor Yanukovych and the restoration of 2004 constitutional amendments.

Also read: India-Egypt Relations

Annexation of Crimea

Crimea is a peninsula on the Northern coast of the Black Sea in Eastern Europe. The population includes mostly ethnic Russians but has Ukrainians and Crimeans as well.

In the 18 th century, Crimea was annexed by the Russian empire. Following the Russian Revolution , Crimea became an autonomous region in the Soviet Union.

In 1954, Soviet leader Nikita Khrushchev, a Ukrainian by birth, transferred Crimea to Ukraine. But the status of Crimea remained disputed since then.

In February 2014, post-Ukrainian Revolution, Russian troops were deployed in Crimea. A referendum on reunification with Russia was held in March in which 90% population favoured joining Russia. Despite opposition from Ukraine, Russia formally annexed Crimea in March 2014.

Read here for in-depth details of the Euromaidan, Ukrainian revolution, and Crimean annexation.

The Minsk agreements between Russia-Ukraine

Following the 2014 Ukraine revolution and the Euromaidan movement, civil unrest erupted in the Donetsk and Luhansk regions (together called the Donbas region) in Eastern Ukraine which borders Russia.

The majority population in these regions are Russians and it has been alleged that Russia fuelled anti-government campaigns there. Russia-backed insurgents and the Ukrainian military engaged in armed confrontations in the region.

In September 2014, talks led to the signing of the Minsk protocol (Minsk I) by the Trilateral Contact Group involving Ukraine, Russia, and the Organisation for the Security and Cooperation in Europe (OSCE). It is a 12 point ceasefire deal involving provisions like weapon removal, prisoner exchanges, humanitarian aid, etc. But the deal broke following violations by both sides.

In 2015, yet another protocol termed Minsk II was signed by the parties. It included provisions to delegate more power to the rebel-controlled regions. But the clauses remain un-implemented due to differences between Ukraine and Russia.

Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe (OSCE)

The Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe (OSCE) is the world’s largest security-oriented intergovernmental organization with observer status at the United Nations. It is based in Vienna, Austria. It has 57 members spanning across Europe, Asia, and North America. India is not a member. Decisions are made by consensus.

Its mandate includes issues such as arms control, promotion of human rights, freedom of the press, and fair elections. It has its origins in the mid-1975 Conference on Security and Co-operation in Europe (CSCE) held in Helsinki, Finland. In 1994, CSCE was renamed the OSCE. It was created during the Cold War era as an East-West forum.

Russia-Ukraine conflict: Present Day

The latest episode of the Russian troop display near the Ukraine border is linked to all the previous issues. Not just Russia, but the United States and the European Union have stakes in Ukraine.

While Russia shares centuries-old cultural ties with Ukraine, the US and the European Union see Ukraine as a buffer between Russia and the West.

Russia seeks assurance from the West that Ukraine would not be made part of NATO which has anti-Russian ambitions. But the US is not ready to budge on Russia’s demands.

The sudden rise in tensions can be attributed to the following factors:

- The newly elected President of Ukraine, Volodymyr Zelensky, has been harsh on Russian supporters in Ukraine and has been going against Moscow’s interests.

- Perceivably undecisive administration in the US under the new President Joe Biden and Washington’s chaotic exit from Afghanistan.

- Russian President Vladimir Putin’s immense interest in Ukraine. Putin maintains that Ukraine is the “red line” the West must not cross.

India’s stand on Russia- Ukraine conflict

India has long maintained a cautious silence on the Russia-Ukraine conflict issue. But recently India has spoken in the matter and called for peaceful resolution of the issue through sustained diplomatic efforts for long-time peace and stability.

New Delhi and Moscow have a time-tested and reliable relationship especially with Russia being a major arms supplier to India.

India has risked US sanctions under Countering America’s Adversaries Through Sanctions Act (CAATSA) by the buying S-400 missile defence system from Russia.

On the other hand, India also needs the support of the US and EU in balancing its strategic calculus.

It is also worthwhile to note that India had abstained from voting in a United Nations resolution upholding Ukraine’s territorial integrity following Russia’s Crimean annexation in 2014.

Even this time, India is maintaining a patient approach by hoping that the situation will be handled peacefully by skilful negotiators.

Way forward

The Russia-Ukraine conflict is threatening the delicate balance the world is in right now and escalation can have manifold impacts on a global scale. There is a strong case for de-escalation, as a peaceful culmination of severed relations is for the good of everyone in the region and the world over.

The US can play a central role in the management of the Russia- Ukraine conflict with support from the other European allies like the UK, Germany, and France.

Negotiations and strategic investments should be aimed at creating sustainable resolution of the conflict.

It will not be enough to just smooth over the difficulties, but major attention to be given to structure the military disengagement to minimize the chances of backsliding.

Also read: Butterfly mines

Top 10 Best-Selling ClearIAS Courses

Upsc prelims cum mains (pcm) gs course: unbeatable batch 2025 (online), rs.75000 rs.29000, upsc prelims test series (pts) 2025 (online), rs.9999 rs.4999, upsc mains test series (mts) (online), rs.19999 rs.9999, csat course 2025 (online), current affairs course 2025: important news & analysis (online), ncert foundation course (online), essay writing course for upsc cse (online), ethics course for upsc cse (online), fight back: repeaters program with daily tests (online or offline), rs.55000 rs.25000.

About ClearIAS Team

ClearIAS is one of the most trusted learning platforms in India for UPSC preparation. Around 1 million aspirants learn from the ClearIAS every month.

Our courses and training methods are different from traditional coaching. We give special emphasis on smart work and personal mentorship. Many UPSC toppers thank ClearIAS for our role in their success.

Download the ClearIAS mobile apps now to supplement your self-study efforts with ClearIAS smart-study training.

Don’t lose out without playing the right game!

Follow the ClearIAS Prelims cum Mains (PCM) Integrated Approach.

Join ClearIAS PCM Course Now

UPSC Online Preparation

- Union Public Service Commission (UPSC)

- Indian Administrative Service (IAS)

- Indian Police Service (IPS)

- IAS Exam Eligibility

- UPSC Free Study Materials

- UPSC Exam Guidance

- UPSC Prelims Test Series

- UPSC Syllabus

- UPSC Online

- UPSC Prelims

- UPSC Interview

- UPSC Toppers

- UPSC Previous Year Qns

- UPSC Age Calculator

- UPSC Calendar 2024

- About ClearIAS

- ClearIAS Programs

- ClearIAS Fee Structure

- IAS Coaching

- UPSC Coaching

- UPSC Online Coaching

- ClearIAS Blog

- Important Updates

- Announcements

- Book Review

- ClearIAS App

- Work with us

- Advertise with us

- Privacy Policy

- Terms and Conditions

- Talk to Your Mentor

Featured on

and many more...

ClearIAS Programs: Admissions Open

Thank You 🙌

UPSC CSE 2025: Study Plan

Subscribe ClearIAS YouTube Channel

Get free study materials. Don’t miss ClearIAS updates.

Subscribe Now

Download Self-Study Plan

Analyse Your Performance and Track Your Progress

Download Study Plan

IAS/IPS/IFS Online Coaching: Target CSE 2025

Cover the entire syllabus of UPSC CSE Prelims and Mains systematically.

Enter your email address and we'll make sure you're the first to know about any new Brookings Essays, or other major research and recommendations from Brookings Scholars.

[[[A twice monthly update on ideas for tax, business, health and social policy from the Economic Studies program at Brookings.]]]

A personal reflection on a nation's dream of independence and the nightmare Vladimir Putin has visited upon it.

Chrystia freeland.

May 12, 2015

O n March 24 last year, I was in my Toronto kitchen preparing school lunches for my kids when I learned from my Twitter feed that I had been put on the Kremlin's list of Westerners who were banned from Russia. This was part of Russia's retaliation for the sanctions the United States and its allies had slapped on Vladimir Putin's associates after his military intervention in Ukraine.

For the rest of my grandparents' lives, they saw themselves as political exiles with a responsibility to keep alive the idea of an independent Ukraine.

Four days earlier, nine people from the U.S. had been similarly blacklisted, including John Boehner, the speaker of the House of Representatives, Harry Reid, then the majority leader of the Senate, and three other senators: John McCain, a long-time critic of Putin, Mary Landrieu of Louisiana, and Dan Coats of Indiana, a former U.S. ambassador to Germany. “While I'm disappointed that I won't be able to go on vacation with my family in Siberia this summer,” Coats wisecracked, “I am honored to be on this list.”

I, however, was genuinely sad to be barred from Russia. I think of myself as a Russophile. I speak the language and studied the nation's literature and history in college. I loved living in Moscow in the mid-nineties as bureau chief for the Financial Times and have made a point of returning regularly over the subsequent fifteen years.

Speaking in #Toronto today, we must continue to support the Maidan & a democratic #Ukraine . pic.twitter.com/c6r2K63GDO — Chrystia Freeland (@cafreeland) February 23, 2014

I'm also a proud member of the Ukrainian-Canadian community. My maternal grandparents fled western Ukraine after Hitler and Stalin signed their non-aggression pact in 1939. They never dared to go back, but they stayed in close touch with their brothers and sisters and their families, who remained behind. For the rest of my grandparents' lives, they saw themselves as political exiles with a responsibility to keep alive the idea of an independent Ukraine, which had last existed, briefly, during and after the chaos of the 1917 Russian Revolution. That dream persisted into the next generation, and in some cases the generation after that.

My late mother moved back to her parents' homeland in the 1990s when Ukraine and Russia, along with the thirteen other former Soviet republics, became independent states. Drawing on her experience as a lawyer in Canada, she served as executive officer of the Ukrainian Legal Foundation, an NGO she helped to found.

My mother was born in a refugee camp in Germany before the family immigrated to western Canada. They were able to get visas thanks to my grandfather's older sister, who had immigrated between the wars. Her generation, and an earlier wave of Ukrainian settlers, had been actively recruited by successive Canadian governments keen to populate the vast prairies of Manitoba, Saskatchewan, and Alberta.

Today, Canada's Ukrainian community, which is 1.25 million-strong, is significantly larger as a percentage of total population than the one in the United States, which is why it is also a far more significant political force. And that in turn probably accounts for the fact that while there were no Ukrainian-Americans on the Kremlin's blacklist, four of the thirteen Canadians singled out were of Ukrainian extraction: in addition to myself, my fellow Member of Parliament James Bezan, Senator Raynell Andreychuk, and Paul Grod, who has no national elective role, but is head of the Ukrainian Canadian Congress.

Until March of last year, none of this prevented my getting a Russian visa. I was, on several occasions, invited to moderate panels at the St. Petersburg International Economic Forum, the Kremlin's version of the World Economic Forum in Davos. Then, in 2013, Medvedev agreed to let me interview him in an off-the-record briefing for media leaders at the real Davos annual meeting.

That turned out to be the last year when Russia, despite its leadership's increasingly despotic and xenophobic tendencies, was still, along with the major Western democracies and Japan, a member in good standing of the G-8. Russia in those days was also part of the elite global group Goldman Sachs had dubbed the BRICs — the acronym stands for Brazil, Russia, India, and China — the emerging market powerhouses that were expected to drive the world economy forward. Putin was counting on the $50 billion extravaganza of the 2014 Sochi Winter Olympics to further solidify Russia's position at the high table of the international community.

President Viktor Yanukovych's flight from Ukraine in the face of the Maidan uprising, which took place on the eve of the closing day of those Winter Games, astonished and enraged Putin. In his pique, as Putin proudly recalled in a March 2015 Russian government television film, he responded by ordering the takeover of Crimea after an all-night meeting. That occurred at dawn on the morning of February 23, 2014, the finale of the Sochi Olympics. The war of aggression, occupation, and annexation that followed turned out to be the grim beginning of a new era, and what might be the start of a new cold war, or worse.

Putin's Big Lie

Chapter 1: putin's big lie.

T he crisis that burst into the news a year-and-a-half ago has often been explained as Putin's exploitation of divisions between the mainly Russian-speaking majority of Ukrainians in the eastern and southern regions of the country, and the mainly Ukrainian-speaking majority in the west and center. Russian is roughly as different from Ukrainian as Spanish is from Italian.

Russian is roughly as different from Ukrainian as Spanish is from Italian.

While the linguistic factor is real, it is often oversimplified in several respects: Russian-speakers are by no means all pro-Putin or secessionist; Russian- and Ukrainian-speakers are geographically commingled; and virtually everyone in Ukraine has at least a passive understanding of both languages. To make matters more complicated, Russian is the first language of many ethnic Ukrainians, who are 78 percent of the population (but even that category is blurry, because many people in Ukraine have both Ukrainian and Russian roots). President Petro Poroshenko is an example — he always understood Ukrainian, but learned to speak it only in 1996, after being elected to Parliament; and Russian remains the domestic language of the Poroshenko family. The same is true in the home of Arseniy Yatsenyuk, Ukraine's prime minister. The best literary account of the Maidan uprising to date was written in Russian: Ukraine Diaries , by Andrey Kurkov, the Russian-born, ethnic Russian novelist, who lives in Kyiv .

Being a Russian-speaker in Ukraine does not automatically imply a yearning for subordination to the Kremlin any more than speaking English in Ireland or Scotland means support for a political union with England.

In this last respect, my own family is, once again, quite typical. My maternal grandmother, born into a family of Orthodox clerics in central Ukraine, grew up speaking Russian and Ukrainian. Ukrainian was the main language of the family refuge she eventually found in Canada, but she and my grandfather spoke Ukrainian and Russian as well as Polish interchangeably and with equal fluency. When they told stories, it was natural for them to quote each character in his or her original language. I do the same thing today with Ukrainian and English, my mother having raised me to speak both languages, as I in turn have done with my three children.

In short, being a Russian-speaker in Ukraine does not automatically imply a yearning for subordination to the Kremlin any more than speaking English in Ireland or Scotland means support for a political union with England. As Kurkov writes in his Diaries : “I am a Russian myself, after all, an ethnically Russian citizen of Ukraine. But I am not 'a Russian,' because I have nothing in common with Russia and its politics. I do not have Russian citizenship and I do not want it.”

That said, it's true that people on both sides of the political divide have tried to declare their allegiances through the vehicle of language. Immediately after the overthrow and self-exile of Yanukovych, radical nationalists in Parliament passed a law making Ukrainian the sole national language — a self-destructive political gesture and a gratuitous insult to a large body of the population.

However, the contentious language bill was never signed into law by the acting president. Many civic-minded citizens also resisted such polarizing moves. As though to make amends for Parliament's action, within 72 hours the people of Lviv, the capital of the Ukrainian-speaking west, held a Russian-speaking day, in which the whole city made a symbolic point of shifting to the country's other language.

Russians see Ukraine as the cradle of their civilization. Even the name came from there: the vast empire of the czars evolved from Kyivan Rus , a loose federation of Slavic tribes in the Middle Ages.

Less than two weeks after the language measure was enacted it was rescinded, though not before Putin had the chance to make considerable hay out of it.

The blurring of linguistic and ethnic identities reflects the geographic and historic ties between Ukraine and Russia. But that affinity has also bred, among many in Russia, a deep-seated antipathy to the very idea of a truly independent and sovereign Ukrainian state.

The ties that bind are also contemporary and personal. Two Soviet leaders — Nikita Khrushchev and Leonid Brezhnev — not only spent their early years in Ukraine but spoke Russian with a distinct Ukrainian accent. This historic connectedness is one reason why their post-Soviet successor, Vladimir Putin, has been able to build such wide popular support in Russia for championing — and, as he is now trying to do, recreating — “Novorossiya” (New Russia) in Ukraine.

Many Russians have themselves been duped into viewing Washington, London, and Berlin as puppet-masters attempting to destroy Russia.

In selling his revanchist policy to the Russian public, Putin has depicted Ukrainians who cherish their independence and want to join Europe and embrace the Western democratic values it represents as, at best, pawns and dupes of NATO — or, at worst, neo-Nazis. As a result, many Russians have themselves been duped into viewing Washington, London, and Berlin as puppet-masters attempting to destroy Russia.

Click here to learn more about the linguistic kinship

The linguistic kinship between Russian and Ukrainian has been an advantage to some, Freeland explains, but the familiarity has also caused problems.

For individual Ukrainians, though less often for the country as whole, this linguistic kinship has sometimes been an advantage. Nikolai Gogol, known to Ukrainians as Mykola Hohol, was the son of prosperous Ukrainian gentleman farmer. His first works were in Ukrainian, and he often wrote about Ukraine. But he entered the international literary canon as a Russian writer, a feat he is unlikely to have accomplished had Dead Souls been written in his native language. Many ethnic Ukrainians were likewise successful in the Soviet nomenklatura, where these so-called “younger brothers” of the ruling Russians had a trusted and privileged place, comparable to the role of Scots in the British Empire.

But familiarity can also breed contempt. Russia's perceived kinship with Ukrainians often slipped into an attempt to eradicate them. These have ranged from Tsar Alexander II's 1876 Ems Ukaz , which banned the use of Ukrainian in print, on the stage or in public lectures and the 1863 Valuev ukaz which asserted that “the Ukrainian language has never existed, does not exist, and cannot exist,” to Stalin's genocidal famine in the 1930s.

This subterfuge is, arguably, Putin's single most dramatic resort to the Soviet tactic of the Big Lie. Through his virtual monopoly of the Russian media, Putin has airbrushed away the truth of what happened a quarter of a century ago: the dissolution of the USSR was the result not of Western manipulation but of the failings of the Soviet state, combined with the initiatives of Soviet reformist leaders who had widespread backing from their citizens. Moreover, far from conspiring to tear the USSR apart, Western leaders in the late 1980s and early nineties used their influence to try to keep it together.

It all started with Mikhail Gorbachev, who, when he came to power in 1985, was determined to revitalize a sclerotic economy and political system with perestroika (literally, rebuilding), glasnost (openness), and a degree of democratization.

These policies, Gorbachev believed, would save the USSR. Instead, they triggered a chain reaction that led to its collapse. By softening the mailed-fist style of governing that traditionally accrued to his job, Gorbachev empowered other reformers — notably his protégé-turned-rival Boris Yeltsin — who wanted not to rebuild the USSR but to dismantle it.

Their actions radiated from Moscow to the capitals of the other Soviet republics — most dramatically Kyiv (then known to most of the world by its Russian name, Kiev). Ukrainian democratic reformers and dissidents seized the chance to advance their own agenda — political liberalization and Ukrainian statehood — so that their country could be free forever from the dictates of the Kremlin.

However, they were also pragmatists. Recognizing that after centuries of rule from Moscow, Ukraine's national consciousness was weak while its Communist Party was strong, they cut a tacit deal with the Ukrainian political leadership: in exchange for the Communists' support for independence, the democratic opposition would postpone its demands for political and economic reform.

By 1991, the centrifugal forces in the Soviet Union were coming to a head. Putin, in his rewrite of history, would have the world believe that the United States was cheering and covertly supporting secessionism. On the contrary, President George H.W. Bush was concerned that the breakup of the Soviet Union would be dangerously destabilizing. He had put his chips on Gorbachev and reform Communism and was skeptical about Yeltsin. In July of that year, Bush traveled first to Moscow to shore up Gorbachev, then to Ukraine, where, on August 1, he delivered a speech to the Ukrainian Parliament exhorting his audience to give Gorbachev a chance at keeping a reforming Soviet Union together: “Americans will not support those who seek independence in order to replace a far-off tyranny with a local despotism. They will not aid those who promote a suicidal nationalism based upon ethnic hatred.”

I was living in Kyiv at the time, working as a stringer for the FT , The Economist , and The Washington Post . Listening to Bush in the parliamentary press gallery, I felt he had misread the growing consensus in Ukraine. That became even clearer immediately afterward when I interviewed Ukrainian members of Parliament (MPs), all of whom expressed outrage and scorn at Bush for, as they saw it, taking Gorbachev's side. The address, which New York Times columnist William Safire memorably dubbed the “Chicken Kiev speech,” backfired in the United States as well, antagonizing Americans of Ukrainian descent and other East European diasporas, which may have hurt Bush's chances of reelection, costing him support in several key states.

But Bush was no apologist for Communism. His speech was heavily influenced by Condoleezza Rice, not a notable soft touch, and it echoed the United Kingdom's Iron Lady, Margaret Thatcher, who, a year earlier, had said she could no more imagine opening a British embassy in Kyiv than in San Francisco.

The magnitude of the West's miscalculation, and Gorbachev's, became clear less than a month later. On August 19, a feckless attempt by Russian hardliners to overthrow Gorbachev triggered a stampede to the exits by the non-Russian republics, especially in the Baltic States and Ukraine. On August 24, in Kyiv , the MPs Bush had lectured three weeks earlier voted for independence.

The world would almost certainly never have heard of Putin had it not been for the dissolution of the USSR, which Putin has called “the greatest geopolitical catastrophe of the 20th century.”

Three months after that, I sat in my Kyiv studio apartment — on a cobblestone street where the Russian-language writer Mikhail Bulgakov once lived — listening to Gorbachev's televised plea to the Ukrainian people not to secede. He invoked his maternal grandmother who (like mine) was Ukrainian; he rhapsodized about his happy childhood in the Kuban in southern Russia, where the local dialect is closer to Ukrainian than to Russian. He quoted — in passable Ukrainian — a verse from Taras Shevchenko, a serf freed in the 19th century who became Ukraine's national poet. Gorbachev was fighting back tears as he spoke.

What does "My Ukraine" mean to you?

Share a thought or photo using #MyUkraine.