- Using Easy Cite Using Easy Cite

- RMIT Harvard RMIT Harvard

- AGLC4 AGLC4

- APA 7 th ed. APA 7 th ed.

- Chicago A Chicago A

- Chicago B Chicago B

- Vancouver Vancouver

How to use the Easy Cite referencing guide

Easy cite lets you look up referencing tips and examples in a selection of common styles used at rmit..

The styles included are RMIT Harvard, AGLC4, APA, Chicago A: footnotes and bibliography, Chicago B: author-date, IEEE, and Vancouver.

Easy Cite includes as many examples of reference types as possible. If the style guides shown here do not include your specific reference or citation type, consider applying the format from similar types within Easy Cite for your reference and citation, or check the relevant style manual.

Easy Cite is intended as a guide only and some styles are open to interpretation. You should always check with your instructor to ensure you are using the correct style for your assignments and assessment tasks.

Visit the Learning Lab Referencing Tutorial (opens in a new tab) and find out how to correctly use different referencing styles in academic writing to avoid plagiarism and get better marks.

Select a style guide from the tabs above to start using Easy Cite. Or view this instructional video first...

Video transcript (RTF)

Easy Cite referencing guide

Easy Cite referencing guide by RMIT University Library is licensed under Creative Commons CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 .

This resource is derived from a work by Swinburne University Library , based on an original work by Griffith University Library .

(links open in new tabs)

© RMIT University Library

Library tutorials

Artificial intelligence - referencing guidelines, using generative artificial intelligence (ai) in learning and research, including assessment tasks, overview of text-generating ai tools, apa 7th - reference ai tools as software, rmit harvard - interim guidelines, chicago a - interim guidelines, chicago b - interim guidelines, vancouver - interim guidelines, ieee - interim guidelines, aglc - interim guidelines.

- Referencing AI-generated images

Easy Cite Referencing Tool

The educators within your courses can tell you if you are able to use artificial intelligence (AI) tools in your assessment tasks, including how you can use the tools and what tools you can use. If you use any AI tools, you must appropriately acknowledge and reference the use of these tools and their outputs. Failure to reference the use of these tools can result in academic misconduct .

Please confirm with your course educator before using any AI tools in your assessment tasks.

Please note that the guidelines on how to reference AI tools have been updated in January 2024. This is in response to updated functionality in some tools, including the ability to generate shareable URLs.

We have also created guidelines for referencing AI-generated images on the second part of this guide.

Introduction to AI tools that can generate text

AI tools that generate text, such as RMIT's Val and OpenAI's ChatGPT, are large language models with a conversational type of interface, where you can ask a question, receive a detailed response and follow up with additional queries.

Some generative AI tools are not connected to the internet and are trained on data sets up to a specific time point. Other generative AI tools connect to the internet and will provide URL links to information. There are some points to consider when using the text generated by these tools:

- As these tools function in a similar way to predictive text on your phone, by recognising and reproducing patterns in language, they can generate incorrect information.

- While they can produce citations and references, these are not always correct. If you are relying on the information to be accurate, you should check that the reference cited by the AI tool exists, and that the information cited is present in the original source.

- The data sets used to train these tools often include biased and inaccurate information, as access to scholarly information and valid scientific studies may be limited, and information from social media and other less reputable sources is included.

The Learning Lab Artificial Intelligence Tools module has more information on how these AI tools work, and some points to consider when using them.

Copyright and non-human authors

Current copyright law only recognises humans as authors and creators. One of the moral rights associated with copyright is the right to be acknowledged as the author of a work. From a copyright perspective an AI tool cannot be recognised as the creator of a work , however it is important to explain that an AI tool was used in the creation of the work. This has informed our referencing guidance.

General acknowledgement that AI tools have been used in the creation of a work

In some assessment tasks, you may be able to use AI tools for background research, or to generate an outline for your essay or report. As stated earlier, please follow your educator's guidance before using any AI tools. In this case, rather than citing and referencing specific text generated by AI tools, you will need to provide a general acknowledgement within the body or methods section of your text to explain that an AI tool was used in the creation of your work. Include as much detail as possible, including how you used the AI tool, the prompt used, the date you used the tool, and the name, creator and version of the AI tool.

Example: On the 26th June 2023, I used the May 24 version of OpenAI's ChatGPT to perform background research by using the following prompt "explain the difference between deep learning and machine learning".

Referencing specific text content generated by AI tools

Each of the referencing styles used at RMIT is based on a source style manual. More information on the source style manuals used for each style can be found in Easy Cite . Currently, only the editors of the APA style manual have provided advice on referencing AI-generated content. For the other referencing styles used at RMIT, we have created interim guidelines for referencing AI-generated content that we believe are the best match within that style. These may change in the future as the source style manuals develop or update their guidelines for referencing AI-generated content.

If you are referring to content generated by AI tools within your work, we recommend that you include the shareable link to the content if available, or otherwise include this AI-generated content as an appendix or supplemental information. It is also good practice to include the question or prompt that generated the response to provide context for your readers.

Two sets of reference guidelines are provided below for each style - one is for AI tools that include shareable URLs to the outputs generated from text prompts, which enables your readers to access the outputs themselves. The other is for AI tools that do not provide shareable links, meaning that the readers of your work cannot access the same information themselves.

The current (April 2023) guidelines from the APA style manual editors are to reference outputs from AI tools such as ChatGPT in a similar way to referencing software outputs. Use the name of the creator of the tool as the author and include both an in-text citation and a reference list entry. If a shareable URL to the content is available, include it in your reference list entry. If the content is not shareable, include the prompt used and the output generated in an appendix. Include the general URL for the tool and a note about the appendix in the reference list entry.

In-text citations:

For in-text citations, use the creator of the AI tool as the author (i.e., OpenAI), and the year of the version of the AI model that you have used.

Rule for narrative (author-prominent) citations: Author (year)

Example 1: OpenAI (2023)

Example 2: Anthropic (2024)

Example 3: RMIT (2024)

Rule for parenthetical (information-prominent) citations: (Author, year)

Example 1: (OpenAI, 2023)

Example 2: (Anthropic, 2024)

Example 3: (RMIT, 2024)

Reference list entry example - shareable URL generated by the AI tool:

Rule: Author. (Year). Title of software program (Version) [Format]. Publisher*. URL

*Note: when the publisher and author name are the same, do not repeat the publisher name after the format, and instead move directly to the URL. Include details of the version if known.

Example: OpenAI. (2023). ChatGPT (May 24 version) [Large language model].

https://chat.openai.com/share/81f2e81f-f137-41b6-9881-39af1672ae3c

Reference list entry example - non-shareable AI-generated content:

Rule: Author. (Year). Title of software program (Version) [Format]. Publisher*. URL. Appendix.

*Note: when the publisher and author name are the same, do not repeat the publisher name after the format, and instead move directly to the URL. Include details of the version if known.

Example: Anthropic. (2024). Claude [Large language model]. https://claude.ai/chats. See Appendix for prompt used and output generated.

Example: RMIT. (2024). Val [Large language model]. https://val.rmit.edu.au/. See Appendix for prompt used and output generated.

The Australian Government Style Manual, on which our RMIT Harvard referencing style is based, currently contains no guidelines for referencing AI-generated content, and also has no guidelines for referencing software programs. As the RMIT Harvard style is similar to the APA 7th style, we have based the interim guidelines for RMIT Harvard on the current APA guidelines for referencing AI-generated content, adapted to match the RMIT Harvard style. Please note these are interim guidelines and these may be updated in the future if the Australian Government Style Manual editors release formal advice.

Use the name of the creator of the tool as the author and include both an in-text citation and a reference list entry. If a shareable URL to the content is available, include it in your reference list entry. If the content is not shareable, include the prompt used and the output generated in an appendix. Include the general URL for the tool and a note about the appendix in the reference list entry.

Example 1: (OpenAI 2023)

Example 2: (Anthropic 2024)

Example 3: (RMIT 2024)

Rule: Author (Year) Title of software program (Version) [Format], Publisher*, accessed Day Month Year. URL

*Note: when the publisher and author name are the same, do not repeat the publisher name after the format, and instead move directly to the URL. Include details of the version if known.

Example: OpenAI (2023) ChatGPT (May 24 version) [Large language model], accessed 26 June 2023. https://chat.openai.com/share/81f2e81f-f137-41b6-9881-39af1672ae3c

Rule: Author (Year) Title of software program (Version) [Format], Publisher*, accessed Day Month Year. URL. Appendix.

Example: Anthropic (2024). Claude [Large language model], accessed 22 January 2024. https://claude.ai/chats. See Appendix for prompt used and output generated.

Example: RMIT (2024). Val [Large language model], accessed 27 February 2024. https://val.rmit.edu.au/. See Appendix for prompt used and output generated.

The Chicago Manual of Style editors have released a Q&A post on referencing AI-generated text. We have adapted these guidelines to accommodate the current Australian copyright advice that AI tools cannot be listed as authors - instead write that the text was generated using [the AI tool].

If a shareable URL to the content is available, include it in your reference list entry. If the content is not shareable, include the prompt used and the output generated in an appendix. Include the general URL for the tool and a note about the appendix in the reference list entry.

Chicago A (footnotes)

The Chicago A (footnote) style uses numbered in-text citations that match the corresponding footnote or endnote entry.

Footnote example - shareable URL generated by the AI tool:

Rule: Note number. AI tool used, Month Day, Year, Creator of tool, URL.

Example: 1. Text generated using ChatGPT, June 26, 2023, OpenAI, https://chat.openai.com/share/81f2e81f-f137-41b6-9881-39af1672ae3c

Footnote example - non-shareable AI-generated content:

Rule: Note number. AI tool used, Month Day, Year, Creator of tool, URL, Appendix.

Example: 1. Text generated using Claude, January 22, 2024, Anthropic, https://claude.ai/chats, see Appendix for prompt used and output generated.

Example: 1. Text generated using Val, February 27, 2024, RMIT, https://val.rmit.edu.au/, see Appendix for prompt used and output generated.

The Chicago Manual of Style editors have released a Q&A post on referencing AI-generated text. We have adapted these guidelines to accommodate the current Australian copyright advice that AI tools cannot be listed as authors. Instead, use the creator of the tool as the author in the in-text citation and provide bibliographic details in a reference list entry.

Chicago B (author-date)

The Chicago B (author-date) style uses an author-date format for in-text citations and a corresponding reference list.

In-text citation - narrative (author-prominent):

Rule: Author (year)

Example: OpenAI (2023)

Example: Anthropic (2024)

Example: RMIT (2024)

In-text citation - parenthetical (information-prominent):

Rule: (Author year)

Example: (OpenAI 2023)

Example: (Anthropic 2024)

Example (Val 2024)

Rule: Author. Year. Name of tool . Version (if available). Month Day, Year. URL

Example: OpenAI. 2023. ChatGPT . May 24 version. June 26, 2023. https://chat.openai.com/share/81f2e81f-f137-41b6-9881-39af1672ae3c

Rule: Author. Year. Name of tool . Version (if available). Month Day, Year. URL. Appendix.

Example: Anthropic. 2024. Claude. January 22, 2024. https://claude.ai/chats. See Appendix for prompt used and output generated.

Example: RMIT. 2024. Val . February 27, 2024. https://val.rmit.edu.au/. See Appendix for prompt used and output generated.

The RMIT Vancouver guide is based on the e-book Citing Medicine: The NLM Style Guide for Authors, Editors, and Publishers [Internet]. 2nd edition. The NLM Style Guide does not currently contain any guidelines for referencing AI-generated content, however the International Community of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE) has released guidance on the use of generative AI tools in scholarly work published in medical journals . The advice is that generative AI tools should not be listed or cited as authors, and that the use of AI tools must be acknowledged.

The NLM style guide includes guidelines for referencing a number of internet source types. We have adapted these guidelines below, as we believe this is the best match for the style. Please note these are interim guidelines and these may be updated in the future when the NLM style manual editors release formal advice.

Use the name of the creator of the tool as the author. Include details of the version if known. If a shareable URL to the content is available, include it in your reference list entry. If the content is not shareable, include the prompt used and the output generated in an appendix. Include the general URL for the tool and a note about the appendix in the reference list entry.

The Vancouver style uses numbered in-text citations that match the corresponding footnote or endnote entry.

Rule: Reference number. Name of AI tool [Type of medium]. Creator of tool; Date of version YYYY Mon [cited YYYY Mon DD]. Available from URL

Example: 1. ChatGPT [Internet]. OpenAI; 2023 May [cited 2023 Jun 26]. Available from https://chat.openai.com/share/81f2e81f-f137-41b6-9881-39af1672ae3c

Rule: Reference number. Name of AI tool [Type of medium]. Creator of tool; Date of version YYYY Mon [cited YYYY Mon DD]. URL. Appendix.

Example: 1. Claude [Internet]. Anthropic [cited 2024 Jan 22]. https://claude.ai/chats. See Appendix for prompt used and output generated.

Example: 1. Val [Internet]. RMIT [cited 2024 Feb 27]. https://val.rmit.edu.au/. See Appendix for prompt used and output generated.

The IEEE referencing guide does not currently contain any guidelines for referencing AI-generated content, but the style guide does include guidelines for referencing software. We have adapted the software guidelines below, as we believe this is the best match for the style. Please note these are interim guidelines and these may be updated in the future when the IEEE style manual editors release formal advice.

The IEEE referencing style uses numbered in-text citations that match the corresponding reference list entry.

Include details of the version if known. If a shareable URL to the content is available, include it in your reference list entry. If the content is not shareable, include the prompt used and the output generated in an appendix. Include the general URL for the tool and a note about the appendix in the reference list entry.

Template: Reference number. Title of Software. (version or year), Publisher Name. Accessed: Mon. DD, YYYY. [Type of Medium]. Available: site/path/file

Example: 1. ChatGPT (May 24 Version), OpenAI. Accessed: Jun 23, 2023. [Online]. Available: https://chat.openai.com/share/5a1327c0-e637-4b3c-a3db-c380b8008ca8

Rule: Reference number. Title of Software. (version or year), Publisher Name. Accessed: Mon. DD, YYYY. [Type of Medium]. Available: site/path/file. Appendix.

Example: 1. Claude. (2024), Anthropic. Accessed: Jan 22, 2024. [Online]. Available: https://claude.ai/chats. See Appendix for prompt used and output generated.

Example: 1. Val. (2024), RMIT. Accessed: Feb 27, 2024. [Online]. Available: https://val.rmit.edu.au/. See Appendix for prompt used and output generated.

The Australian Guide to Legal Citation 4th edition does not currently contain any guidelines for referencing AI-generated content, and the style guide does not include guidelines for referencing software.

Our interim advice is to reference AI-generated text as a written correspondence (section 7.12), as we believe this is the best match for the AGLC style. As generative AI tools are not considered authors from a copyright perspective, we recommend using language such as 'response generated using [the creator's AI tool]', rather than using the name of the tool as the author. Please note these guidelines may be updated in the future if the AGLC style manual editors release formal advice.

Rule: Note number Correspondence generated using the AI tool to Recipient, full date, URL

Example: 1 Response generated using OpenAI's ChatGPT to Matt Smith, 23 June 2023, https://chat.openai.com/share/5a1327c0-e637-4b3c-a3db-c380b8008ca8.

Rule: Note number Correspondence generated using the AI tool to Recipient, full date, Appendix.

Example: 1 Response generated using Anthropic's Claude to Matt Smith, 24 January 2024, see Appendix for prompt used and output generated.

Example: 1 Response generated using RMIT's Val to Matt Smith, 27 February 2024, see Appendix for prompt used and output generated.

- Next: Referencing AI-generated images >>

- Last Updated: Feb 27, 2024 3:48 PM

- URL: https://rmit.libguides.com/referencing_AI_tools

Academic genres: the Critical Response

- RMIT University

- Aviation English

- English for Academic Purposes

- Foundation Studies

- IELTS One Skill Retake

- Grammar Fundamentals

- English to Foundation Studies Pathway Bursary

- What makes us different?

- Melbourne for international students

- New Students

- Student Services

- Academic Support

- Activities and Events

- Reaching out support

- Team and Board

- Policies and procedures

- Publication services

- General enquiries

What is a Critical Response?

- a type of writing task, requiring different sections depending on the task requirements

- it may be a ‘response’ to a concept, or an article, or more than one article

- at REW, it requires only two sections: Summary and Discussion

Why is it useful?

- It requires the highly valued academic skills of summarising and critical thought.

- It requires the ability to develop a clear and logical ‘academic argument’, which is extremely important for university and beyond.

- It is a relatively flexible genre, which is both challenging and useful for international students in terms of preparing them for university.

What does my summary need?

A summary can be written in different ways, but ultimately it should:

- give the most important content from a text (whether listening or reading)

- have different wording (i.e. no language copied from the original)

- be significantly shorter than the original

What does my discussion section need?

In each discussion paragraph, you should:

- give one paraphrased idea from the original article/s

- show your 'response' (whether you agree / disagree / partially agree)

- develop your response with more detail

Let's look at some strategies for writing both of these sections.

How do I summarise?

There are many ways to approach this process, but here’s one of the most effective ways: 1. Find the main ideas in your article/s.How do you do this? Look for the following:

- ‘strong’ language, usually shown by adjectives or adverbs (e.g. the most significant / the main reason / terrible / amazing / the best / the worst )

- powerful grammatical structures e.g. short strong simple sentences or sentences that show emphasis (‘It is for this reason that X is important.’ / ‘What makes this significant is...’ / ‘Most importantly, this means...’)

- questions (these sometimes introduce main points, especially if they are at the beginning of a paragraph)

- cause / effect language

2. Paraphrase the main ideas.

The easiest way to do this is by annotating. This means changing the words of the original (and may also include changing word forms and word order of words from the article) and then writing your paraphrases in note form beside the text. Why is this the easiest way? Because then you can copy directly from your notes without worrying about plagiarism.

That’s fine, but don’t expect to pass exams or university courses! 3. Organise your ideas then start writing . Do a quick plan from your notes to make sure you:

- include important points

- paraphrase everything

- have a logical order

- can see where main points can be connected

Here's an example of a plan:

Not so clever country?

- higher taxes are paid

- communities benefit because more jobs and more active economy

- ability to think critically

- specialist skills

- less burden on health care system

- less likely to commit crimes

Ideas from article 'Not so clever country?' in RMIT English Worldwide Advanced Passport book

Now you're ready to write! Remember to first put your heading: Summary. Your first sentence should include:

- the author’s full name (or authors' names if you have two or more)

- the title of the article/s

- the year of the article/s

- the overall topic of the article/s (or their overall position/s)

Then, connect all of the main points together using:

- your own words (avoid copying anything from the original article)

- linking words e.g. First / The author adds that / Thirdly, / Her last point is ... *use the author's family name after the first sentence

- referents e.g. this / it / the / which

- a range of reporting verbs (e.g. claims / states / believes / argues / points out / thinks)

- different sentence structures (simple, compound, complex – if you don’t know how to do this, watch this video )

- academic vocabulary including appropriate collocations

Let's look at an example of a single summary. Note the reporting verbs (in yellow) are in present tense. Even if some of your main points have different verb tenses, you should always keep reporting verbs in present simple.

Summary In the article 'Not so clever country?', Marion Jacobs (2010) argues that cuts to funding for universities have a negative impact. She believes that universities should be supported because of the economic and societal benefits they provide. The economic advantages she explains include more taxes from graduates and extra jobs and income for local communities. Lastly, Jacobs claims that benefits for society include not only graduates' ability to think critically and their specialist skills, but also that they are less of a burden on the health care system and are less likely to commit crimes. (95 words)

What if I need to talk about two articles?

Then you can either summarise them separately or together – use the one you prefer or the most suitable according to the number of main points in the articles. If you put the summaries together, you will have contrasting language between the different articles’ main ideas e.g. while / whereas / but / however. If you do two separate summaries, you will only need one contrast linking word in the first sentence of second article’s summary. You can see all these concepts highlighted below in the example of two summaries:

Two summaries together

In the articles ‘How much English is enough’ (2011) by Jane Cuthbert and ‘Globish? It just doesn’t make sense’ (2014) by Peter Jackson , Globish, a simplified version of English, is discussed. While Cuthbert argues that Globish is a useful development in English language teaching, Jackson thinks that it is idealistic and will not work in reality. He believes that the lack of grammar in Globish can cause misunderstandings, whereas Cuthbert states that Globish does not focus on accuracy and is therefore easier to teach or study independently. In addition , she claims that being independent of culture and limited in vocabulary size are benefits of Globish; however, Jackson feels that it is impossible for language to be separated from culture, as well as the fact that Globish’s limited vocabulary may not be enough for business or deeper levels of communication.

(139 words)

Two separate summaries

In the article ‘How much English is enough?’, Jane Cuthbert (2011) discusses the advantages of Globish, while in the article ‘Globish – it just doesn’t make sense” (2014), Peter Jackson considers its limitations. Cuthbert (2011) argues that the reduction in vocabulary size and grammar promotes confidence and that 1500 words is sufficient for communicative purposes. In addition , she believes that there is no culture in Globish, which makes it more accessible for students. Finally , the author states that Globish is not only easier to teach than English, but also more useful in terms of developing learner independence. However, Jackson (2014) argues against Globish. He believes that its simplicity does not mean it is easier to use, because it could lead to communication problems and is not suitable for certain contexts. The writer also argues that the vocabulary range is too small and that culture cannot be separated from language.

(148 words)

Summary - two ways (based on material in the RMIT English Worldwide Advanced Passport book)

What do the colours highlight?

- blue : author's name or referents

- green : linking phrases expressing contrast

- yellow : other linking phrases

It’s important that these are all varied. Why? Because this shows that you can:

- control a range of grammatical structures

- create cohesion (i.e. your sentences flow – like a river!)

- use a range of academic and less common vocabulary (including collocations) accurately and appropriately

- follow academic convention (do things how they want you to at uni)

Note: style variations are possible. For example, if you do summaries separately, you may still like to introduce both authors and articles in the first sentence (like if you put them together) and then do them separately after the first sentence.

What about the discussion section?

I’m glad you asked! This is where you put your own ideas in response to the author’s ideas. Depending on your task requirements, you may need two, three, or even four discussion paragraphs in this section. Each one will show your response and support for your response to an idea from the original article.

What is support?

It’s any extra information that makes your ideas more clear. For example, you might use a reason or two, an example or two, a fact or statistic, or an explanation of a situation to make your response more credible (logical and believable). In reality, you’ll probably mix a few of these together. In the end, what matters is that someone should be able to read what you’ve written and then clearly understand why you’re supporting or criticising what the author has said.

Actually, you can. In fact, you should! The entire academic world in our context is based on shared knowledge, so we all have a responsibility to think carefully about anything we’re told, compare it with what we know, find out more about it, and develop an informed perspective on it that we can support with logical reasoning and evidence . If you don’t do this, you are not meeting the expectations of the academic community.

How can I write a discussion paragraph?

There are many ways, but here’s a good way to try. 1. Choose an idea from the original article. 2. Think about it. What do you know about it? Do you agree or disagree? Partially agree? Why? This is your response and it needs to be very clear throughout the paragraph. 3. Plan the explanation of your response by thinking of ways to support it. To do this, imagine someone doesn’t believe you and keeps asking you ‘Why do you think that?’ or ‘Why does that matter?’. That way you will explain your response and support it with enough detail. Try to think of one or more of the following:

- explanation

- facts / statistics if you can remember them

Exactly like in your summary, use:

- cohesive devices

- different sentence structures

- academic vocabulary including appropriate collocations

There’s one more step that we haven’t looked at yet... Can you guess what it is? 5. Edit what you’ve written! This means re-reading your writing, looking for mistakes and checking that what you said makes sense. This is vital for two main reasons:

- to ensure that your final text is accurate (in a perfect world, with no mistakes!)

- to improve your ability to check your own writing

What mistakes should you look for? Check:

- subject verb agreement

- nouns – are they countable? Should they be singular or plural? Do you need an article?

- verb tenses – are they the right ones?

- linking words + grammar – did you write a clause (subject + verb...) after linking words like ‘because’? Did you write nouns or verb-ing after linking propositions like ‘due to’ and ‘because of’?

- cohesion – did you use words like ‘this’, ‘it’, ‘the’, and ‘which’ to refer to other things in the paragraph?

- sentence structure: e.g. do you have one subject and one main verb in each clause?

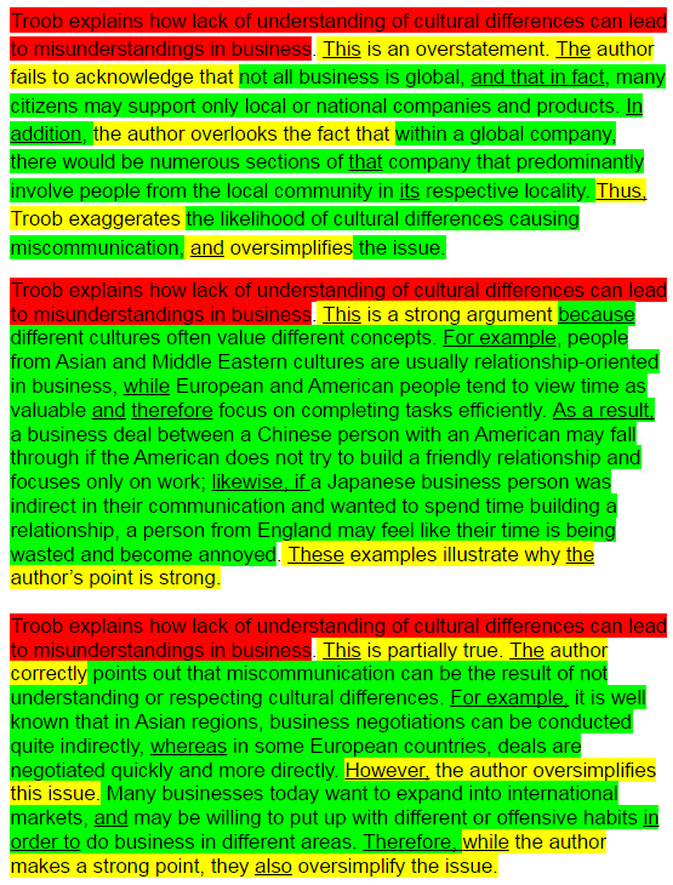

Let’s look at three already edited examples with three different responses. Find the paragraph that:

- supports the author’s idea

- partially agrees with the author’s idea

- disagrees with the author’s idea

Here are some questions to help check if you understand the paragraph structure:

- What is the red section in each paragraph?

- What’s the yellow?

- What’s the green?

- What are the underlined words/phrases?

See if you were right: Answers

- the author’s idea

- my response language

- support for my response

- linking devices (i.e. things that create cohesion)

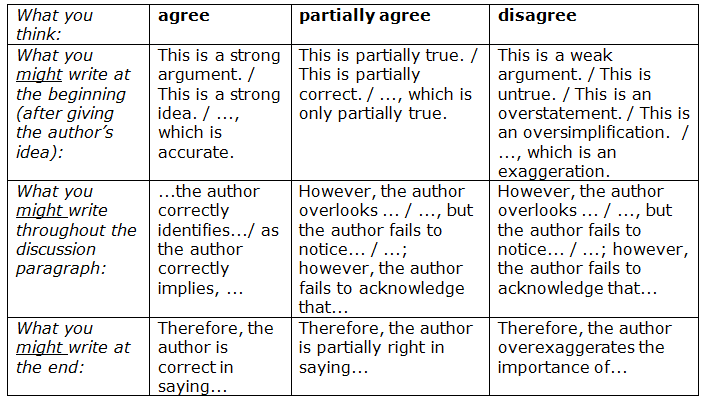

When you write your discussion paragraph, you might use language like this to make your response clear. Which ones are used in the example above?

Why is there no conclusion in these critical responses? It's because they're not a necessary requirement of a critical response task at RMIT Training, although it's ok if you want to write a conclusion once you're sure you have a clear summary and discussion section. In other places around the world, you may always need to do a conclusion. This is why we need to check every time what the task requirements are! Because it's so important to check your own writing, try these ideas if you're not confident about editing:

- watch the sentence structure video on this blog

- try Tense Buster at the RMIT Learning Lab

- download a grammar app

- buy a grammar or academic writing book (see your teacher or a Study Support Teacher for suggestions)

- ask someone like a Study Support Teacher for help

After you've tried these steps, show someone your writing and get their feedback. With a summary, someone must be able to understand the main ideas without seeing the original text, and showing another person is a good way to check this. If they ask questions about what you wrote, you might need to re-write it more clearly. It also helps if you read other people’s writing. Everyone has their own personal writing style, and being exposed to these is helpful for you in terms of developing your style. What are you waiting for? Get started writing the best critical response you've ever written.

- Independent Learning Skills

- Learn English

- Foundation studies

Related articles

RMIT Training is a 2022 Circle Back Initiative Employer – we commit to respond to every applicant

RMIT Training is proud to announce that in 2022, we have joined the Circle Back Initiative to show our commitment to ensure every candidate who applies for a role in our company receives an outcome response.

RMIT English Worldwide announces partnership with COLFUTURO

RMIT Training is thrilled to announce that RMIT English Worldwide (REW) has signed an ELICOS agreement with the prestigious Colombian scholarship body COLFUTURO (the Foundation for the Future of Colombia).

Jake Heinrich appointed Chief Executive Officer of RMIT Training

Experienced international education leader, Jake Heinrich has been appointed Chief Executive Officer of RMIT Training. Heinrich brings extensive experience in the global education sector including more than 25 years of working across Asia, Mexico and Australia.

Acknowledgement of Country

RMIT University acknowledges the people of the Woi wurrung and Boon wurrung language groups of the eastern Kulin Nation on whose unceded lands we conduct the business of the University. RMIT University respectfully acknowledges their Ancestors and Elders, past and present. RMIT also acknowledges the Traditional Custodians and their Ancestors of the lands and waters across Australia where we conduct our business - Artwork 'Luwaytini' by Mark Cleaver, Palawa.

- New students

- Student Wellbeing

- RMIT Training Team and Board

- WGEA Pay Gap Employer Statement

- Copyright © 2024 RMIT University |

- Accessibility |

- Website feedback |

- Complaints |

- RMIT University ABN 49 781 030 034 |

- RMIT Training ABN 61 006 067 349 |

- RMIT University CRICOS provider number: 00122A |

- RMIT Training CRICOS provider number: 01912G |

- Phone: +61 3 9657 5800 |

- Address: 235-251 Bourke Street Melbourne VIC 3000 Australia

Choose Your Test

Sat / act prep online guides and tips, getting college essay help: important do's and don’ts.

College Essays

If you grow up to be a professional writer, everything you write will first go through an editor before being published. This is because the process of writing is really a process of re-writing —of rethinking and reexamining your work, usually with the help of someone else. So what does this mean for your student writing? And in particular, what does it mean for very important, but nonprofessional writing like your college essay? Should you ask your parents to look at your essay? Pay for an essay service?

If you are wondering what kind of help you can, and should, get with your personal statement, you've come to the right place! In this article, I'll talk about what kind of writing help is useful, ethical, and even expected for your college admission essay . I'll also point out who would make a good editor, what the differences between editing and proofreading are, what to expect from a good editor, and how to spot and stay away from a bad one.

Table of Contents

What Kind of Help for Your Essay Can You Get?

What's Good Editing?

What should an editor do for you, what kind of editing should you avoid, proofreading, what's good proofreading, what kind of proofreading should you avoid.

What Do Colleges Think Of You Getting Help With Your Essay?

Who Can/Should Help You?

Advice for editors.

Should You Pay Money For Essay Editing?

The Bottom Line

What's next, what kind of help with your essay can you get.

Rather than talking in general terms about "help," let's first clarify the two different ways that someone else can improve your writing . There is editing, which is the more intensive kind of assistance that you can use throughout the whole process. And then there's proofreading, which is the last step of really polishing your final product.

Let me go into some more detail about editing and proofreading, and then explain how good editors and proofreaders can help you."

Editing is helping the author (in this case, you) go from a rough draft to a finished work . Editing is the process of asking questions about what you're saying, how you're saying it, and how you're organizing your ideas. But not all editing is good editing . In fact, it's very easy for an editor to cross the line from supportive to overbearing and over-involved.

Ability to clarify assignments. A good editor is usually a good writer, and certainly has to be a good reader. For example, in this case, a good editor should make sure you understand the actual essay prompt you're supposed to be answering.

Open-endedness. Good editing is all about asking questions about your ideas and work, but without providing answers. It's about letting you stick to your story and message, and doesn't alter your point of view.

Think of an editor as a great travel guide. It can show you the many different places your trip could take you. It should explain any parts of the trip that could derail your trip or confuse the traveler. But it never dictates your path, never forces you to go somewhere you don't want to go, and never ignores your interests so that the trip no longer seems like it's your own. So what should good editors do?

Help Brainstorm Topics

Sometimes it's easier to bounce thoughts off of someone else. This doesn't mean that your editor gets to come up with ideas, but they can certainly respond to the various topic options you've come up with. This way, you're less likely to write about the most boring of your ideas, or to write about something that isn't actually important to you.

If you're wondering how to come up with options for your editor to consider, check out our guide to brainstorming topics for your college essay .

Help Revise Your Drafts

Here, your editor can't upset the delicate balance of not intervening too much or too little. It's tricky, but a great way to think about it is to remember: editing is about asking questions, not giving answers .

Revision questions should point out:

- Places where more detail or more description would help the reader connect with your essay

- Places where structure and logic don't flow, losing the reader's attention

- Places where there aren't transitions between paragraphs, confusing the reader

- Moments where your narrative or the arguments you're making are unclear

But pointing to potential problems is not the same as actually rewriting—editors let authors fix the problems themselves.

Bad editing is usually very heavy-handed editing. Instead of helping you find your best voice and ideas, a bad editor changes your writing into their own vision.

You may be dealing with a bad editor if they:

- Add material (examples, descriptions) that doesn't come from you

- Use a thesaurus to make your college essay sound "more mature"

- Add meaning or insight to the essay that doesn't come from you

- Tell you what to say and how to say it

- Write sentences, phrases, and paragraphs for you

- Change your voice in the essay so it no longer sounds like it was written by a teenager

Colleges can tell the difference between a 17-year-old's writing and a 50-year-old's writing. Not only that, they have access to your SAT or ACT Writing section, so they can compare your essay to something else you wrote. Writing that's a little more polished is great and expected. But a totally different voice and style will raise questions.

Where's the Line Between Helpful Editing and Unethical Over-Editing?

Sometimes it's hard to tell whether your college essay editor is doing the right thing. Here are some guidelines for staying on the ethical side of the line.

- An editor should say that the opening paragraph is kind of boring, and explain what exactly is making it drag. But it's overstepping for an editor to tell you exactly how to change it.

- An editor should point out where your prose is unclear or vague. But it's completely inappropriate for the editor to rewrite that section of your essay.

- An editor should let you know that a section is light on detail or description. But giving you similes and metaphors to beef up that description is a no-go.

Proofreading (also called copy-editing) is checking for errors in the last draft of a written work. It happens at the end of the process and is meant as the final polishing touch. Proofreading is meticulous and detail-oriented, focusing on small corrections. It sands off all the surface rough spots that could alienate the reader.

Because proofreading is usually concerned with making fixes on the word or sentence level, this is the only process where someone else can actually add to or take away things from your essay . This is because what they are adding or taking away tends to be one or two misplaced letters.

Laser focus. Proofreading is all about the tiny details, so the ability to really concentrate on finding small slip-ups is a must.

Excellent grammar and spelling skills. Proofreaders need to dot every "i" and cross every "t." Good proofreaders should correct spelling, punctuation, capitalization, and grammar. They should put foreign words in italics and surround quotations with quotation marks. They should check that you used the correct college's name, and that you adhered to any formatting requirements (name and date at the top of the page, uniform font and size, uniform spacing).

Limited interference. A proofreader needs to make sure that you followed any word limits. But if cuts need to be made to shorten the essay, that's your job and not the proofreader's.

A bad proofreader either tries to turn into an editor, or just lacks the skills and knowledge necessary to do the job.

Some signs that you're working with a bad proofreader are:

- If they suggest making major changes to the final draft of your essay. Proofreading happens when editing is already finished.

- If they aren't particularly good at spelling, or don't know grammar, or aren't detail-oriented enough to find someone else's small mistakes.

- If they start swapping out your words for fancier-sounding synonyms, or changing the voice and sound of your essay in other ways. A proofreader is there to check for errors, not to take the 17-year-old out of your writing.

What Do Colleges Think of Your Getting Help With Your Essay?

Admissions officers agree: light editing and proofreading are good—even required ! But they also want to make sure you're the one doing the work on your essay. They want essays with stories, voice, and themes that come from you. They want to see work that reflects your actual writing ability, and that focuses on what you find important.

On the Importance of Editing

Get feedback. Have a fresh pair of eyes give you some feedback. Don't allow someone else to rewrite your essay, but do take advantage of others' edits and opinions when they seem helpful. ( Bates College )

Read your essay aloud to someone. Reading the essay out loud offers a chance to hear how your essay sounds outside your head. This exercise reveals flaws in the essay's flow, highlights grammatical errors and helps you ensure that you are communicating the exact message you intended. ( Dickinson College )

On the Value of Proofreading

Share your essays with at least one or two people who know you well—such as a parent, teacher, counselor, or friend—and ask for feedback. Remember that you ultimately have control over your essays, and your essays should retain your own voice, but others may be able to catch mistakes that you missed and help suggest areas to cut if you are over the word limit. ( Yale University )

Proofread and then ask someone else to proofread for you. Although we want substance, we also want to be able to see that you can write a paper for our professors and avoid careless mistakes that would drive them crazy. ( Oberlin College )

On Watching Out for Too Much Outside Influence

Limit the number of people who review your essay. Too much input usually means your voice is lost in the writing style. ( Carleton College )

Ask for input (but not too much). Your parents, friends, guidance counselors, coaches, and teachers are great people to bounce ideas off of for your essay. They know how unique and spectacular you are, and they can help you decide how to articulate it. Keep in mind, however, that a 45-year-old lawyer writes quite differently from an 18-year-old student, so if your dad ends up writing the bulk of your essay, we're probably going to notice. ( Vanderbilt University )

Now let's talk about some potential people to approach for your college essay editing and proofreading needs. It's best to start close to home and slowly expand outward. Not only are your family and friends more invested in your success than strangers, but they also have a better handle on your interests and personality. This knowledge is key for judging whether your essay is expressing your true self.

Parents or Close Relatives

Your family may be full of potentially excellent editors! Parents are deeply committed to your well-being, and family members know you and your life well enough to offer details or incidents that can be included in your essay. On the other hand, the rewriting process necessarily involves criticism, which is sometimes hard to hear from someone very close to you.

A parent or close family member is a great choice for an editor if you can answer "yes" to the following questions. Is your parent or close relative a good writer or reader? Do you have a relationship where editing your essay won't create conflict? Are you able to constructively listen to criticism and suggestion from the parent?

One suggestion for defusing face-to-face discussions is to try working on the essay over email. Send your parent a draft, have them write you back some comments, and then you can pick which of their suggestions you want to use and which to discard.

Teachers or Tutors

A humanities teacher that you have a good relationship with is a great choice. I am purposefully saying humanities, and not just English, because teachers of Philosophy, History, Anthropology, and any other classes where you do a lot of writing, are all used to reviewing student work.

Moreover, any teacher or tutor that has been working with you for some time, knows you very well and can vet the essay to make sure it "sounds like you."

If your teacher or tutor has some experience with what college essays are supposed to be like, ask them to be your editor. If not, then ask whether they have time to proofread your final draft.

Guidance or College Counselor at Your School

The best thing about asking your counselor to edit your work is that this is their job. This means that they have a very good sense of what colleges are looking for in an application essay.

At the same time, school counselors tend to have relationships with admissions officers in many colleges, which again gives them insight into what works and which college is focused on what aspect of the application.

Unfortunately, in many schools the guidance counselor tends to be way overextended. If your ratio is 300 students to 1 college counselor, you're unlikely to get that person's undivided attention and focus. It is still useful to ask them for general advice about your potential topics, but don't expect them to be able to stay with your essay from first draft to final version.

Friends, Siblings, or Classmates

Although they most likely don't have much experience with what colleges are hoping to see, your peers are excellent sources for checking that your essay is you .

Friends and siblings are perfect for the read-aloud edit. Read your essay to them so they can listen for words and phrases that are stilted, pompous, or phrases that just don't sound like you.

You can even trade essays and give helpful advice on each other's work.

If your editor hasn't worked with college admissions essays very much, no worries! Any astute and attentive reader can still greatly help with your process. But, as in all things, beginners do better with some preparation.

First, your editor should read our advice about how to write a college essay introduction , how to spot and fix a bad college essay , and get a sense of what other students have written by going through some admissions essays that worked .

Then, as they read your essay, they can work through the following series of questions that will help them to guide you.

Introduction Questions

- Is the first sentence a killer opening line? Why or why not?

- Does the introduction hook the reader? Does it have a colorful, detailed, and interesting narrative? Or does it propose a compelling or surprising idea?

- Can you feel the author's voice in the introduction, or is the tone dry, dull, or overly formal? Show the places where the voice comes through.

Essay Body Questions

- Does the essay have a through-line? Is it built around a central argument, thought, idea, or focus? Can you put this idea into your own words?

- How is the essay organized? By logical progression? Chronologically? Do you feel order when you read it, or are there moments where you are confused or lose the thread of the essay?

- Does the essay have both narratives about the author's life and explanations and insight into what these stories reveal about the author's character, personality, goals, or dreams? If not, which is missing?

- Does the essay flow? Are there smooth transitions/clever links between paragraphs? Between the narrative and moments of insight?

Reader Response Questions

- Does the writer's personality come through? Do we know what the speaker cares about? Do we get a sense of "who he or she is"?

- Where did you feel most connected to the essay? Which parts of the essay gave you a "you are there" sensation by invoking your senses? What moments could you picture in your head well?

- Where are the details and examples vague and not specific enough?

- Did you get an "a-ha!" feeling anywhere in the essay? Is there a moment of insight that connected all the dots for you? Is there a good reveal or "twist" anywhere in the essay?

- What are the strengths of this essay? What needs the most improvement?

Should You Pay Money for Essay Editing?

One alternative to asking someone you know to help you with your college essay is the paid editor route. There are two different ways to pay for essay help: a private essay coach or a less personal editing service , like the many proliferating on the internet.

My advice is to think of these options as a last resort rather than your go-to first choice. I'll first go through the reasons why. Then, if you do decide to go with a paid editor, I'll help you decide between a coach and a service.

When to Consider a Paid Editor

In general, I think hiring someone to work on your essay makes a lot of sense if none of the people I discussed above are a possibility for you.

If you can't ask your parents. For example, if your parents aren't good writers, or if English isn't their first language. Or if you think getting your parents to help is going create unnecessary extra conflict in your relationship with them (applying to college is stressful as it is!)

If you can't ask your teacher or tutor. Maybe you don't have a trusted teacher or tutor that has time to look over your essay with focus. Or, for instance, your favorite humanities teacher has very limited experience with college essays and so won't know what admissions officers want to see.

If you can't ask your guidance counselor. This could be because your guidance counselor is way overwhelmed with other students.

If you can't share your essay with those who know you. It might be that your essay is on a very personal topic that you're unwilling to share with parents, teachers, or peers. Just make sure it doesn't fall into one of the bad-idea topics in our article on bad college essays .

If the cost isn't a consideration. Many of these services are quite expensive, and private coaches even more so. If you have finite resources, I'd say that hiring an SAT or ACT tutor (whether it's PrepScholar or someone else) is better way to spend your money . This is because there's no guarantee that a slightly better essay will sufficiently elevate the rest of your application, but a significantly higher SAT score will definitely raise your applicant profile much more.

Should You Hire an Essay Coach?

On the plus side, essay coaches have read dozens or even hundreds of college essays, so they have experience with the format. Also, because you'll be working closely with a specific person, it's more personal than sending your essay to a service, which will know even less about you.

But, on the minus side, you'll still be bouncing ideas off of someone who doesn't know that much about you . In general, if you can adequately get the help from someone you know, there is no advantage to paying someone to help you.

If you do decide to hire a coach, ask your school counselor, or older students that have used the service for recommendations. If you can't afford the coach's fees, ask whether they can work on a sliding scale —many do. And finally, beware those who guarantee admission to your school of choice—essay coaches don't have any special magic that can back up those promises.

Should You Send Your Essay to a Service?

On the plus side, essay editing services provide a similar product to essay coaches, and they cost significantly less . If you have some assurance that you'll be working with a good editor, the lack of face-to-face interaction won't prevent great results.

On the minus side, however, it can be difficult to gauge the quality of the service before working with them . If they are churning through many application essays without getting to know the students they are helping, you could end up with an over-edited essay that sounds just like everyone else's. In the worst case scenario, an unscrupulous service could send you back a plagiarized essay.

Getting recommendations from friends or a school counselor for reputable services is key to avoiding heavy-handed editing that writes essays for you or does too much to change your essay. Including a badly-edited essay like this in your application could cause problems if there are inconsistencies. For example, in interviews it might be clear you didn't write the essay, or the skill of the essay might not be reflected in your schoolwork and test scores.

Should You Buy an Essay Written by Someone Else?

Let me elaborate. There are super sketchy places on the internet where you can simply buy a pre-written essay. Don't do this!

For one thing, you'll be lying on an official, signed document. All college applications make you sign a statement saying something like this:

I certify that all information submitted in the admission process—including the application, the personal essay, any supplements, and any other supporting materials—is my own work, factually true, and honestly presented... I understand that I may be subject to a range of possible disciplinary actions, including admission revocation, expulsion, or revocation of course credit, grades, and degree, should the information I have certified be false. (From the Common Application )

For another thing, if your academic record doesn't match the essay's quality, the admissions officer will start thinking your whole application is riddled with lies.

Admission officers have full access to your writing portion of the SAT or ACT so that they can compare work that was done in proctored conditions with that done at home. They can tell if these were written by different people. Not only that, but there are now a number of search engines that faculty and admission officers can use to see if an essay contains strings of words that have appeared in other essays—you have no guarantee that the essay you bought wasn't also bought by 50 other students.

- You should get college essay help with both editing and proofreading

- A good editor will ask questions about your idea, logic, and structure, and will point out places where clarity is needed

- A good editor will absolutely not answer these questions, give you their own ideas, or write the essay or parts of the essay for you

- A good proofreader will find typos and check your formatting

- All of them agree that getting light editing and proofreading is necessary

- Parents, teachers, guidance or college counselor, and peers or siblings

- If you can't ask any of those, you can pay for college essay help, but watch out for services or coaches who over-edit you work

- Don't buy a pre-written essay! Colleges can tell, and it'll make your whole application sound false.

Ready to start working on your essay? Check out our explanation of the point of the personal essay and the role it plays on your applications and then explore our step-by-step guide to writing a great college essay .

Using the Common Application for your college applications? We have an excellent guide to the Common App essay prompts and useful advice on how to pick the Common App prompt that's right for you . Wondering how other people tackled these prompts? Then work through our roundup of over 130 real college essay examples published by colleges .

Stressed about whether to take the SAT again before submitting your application? Let us help you decide how many times to take this test . If you choose to go for it, we have the ultimate guide to studying for the SAT to give you the ins and outs of the best ways to study.

Anna scored in the 99th percentile on her SATs in high school, and went on to major in English at Princeton and to get her doctorate in English Literature at Columbia. She is passionate about improving student access to higher education.

Ask a Question Below

Have any questions about this article or other topics? Ask below and we'll reply!

Improve With Our Famous Guides

- For All Students

The 5 Strategies You Must Be Using to Improve 160+ SAT Points

How to Get a Perfect 1600, by a Perfect Scorer

Series: How to Get 800 on Each SAT Section:

Score 800 on SAT Math

Score 800 on SAT Reading

Score 800 on SAT Writing

Series: How to Get to 600 on Each SAT Section:

Score 600 on SAT Math

Score 600 on SAT Reading

Score 600 on SAT Writing

Free Complete Official SAT Practice Tests

What SAT Target Score Should You Be Aiming For?

15 Strategies to Improve Your SAT Essay

The 5 Strategies You Must Be Using to Improve 4+ ACT Points

How to Get a Perfect 36 ACT, by a Perfect Scorer

Series: How to Get 36 on Each ACT Section:

36 on ACT English

36 on ACT Math

36 on ACT Reading

36 on ACT Science

Series: How to Get to 24 on Each ACT Section:

24 on ACT English

24 on ACT Math

24 on ACT Reading

24 on ACT Science

What ACT target score should you be aiming for?

ACT Vocabulary You Must Know

ACT Writing: 15 Tips to Raise Your Essay Score

How to Get Into Harvard and the Ivy League

How to Get a Perfect 4.0 GPA

How to Write an Amazing College Essay

What Exactly Are Colleges Looking For?

Is the ACT easier than the SAT? A Comprehensive Guide

Should you retake your SAT or ACT?

When should you take the SAT or ACT?

Stay Informed

Get the latest articles and test prep tips!

Looking for Graduate School Test Prep?

Check out our top-rated graduate blogs here:

GRE Online Prep Blog

GMAT Online Prep Blog

TOEFL Online Prep Blog

Holly R. "I am absolutely overjoyed and cannot thank you enough for helping me!”

- RMIT Australia

- RMIT Europe

- RMIT Vietnam

- RMIT Global

- RMIT Online

- Alumni & Giving

- What will I do?

- What will I need?

- Who will help me?

- About the institution

- New to university?

- Studying efficiently

- Time management

- Mind mapping

- Note-taking

- Reading skills

- Argument analysis

- Preparing for assessment

- Critical thinking and argument analysis

- Online learning skills

- Starting my first assignment

- Researching your assignment

- What is referencing?

- Understanding citations

- When referencing isn't needed

- Paraphrasing

- Summarising

- Synthesising

- Integrating ideas with reporting words

- Referencing with Easy Cite

- Getting help with referencing

- Acting with academic integrity

- Artificial intelligence tools

- Understanding your audience

- Writing for coursework

- Literature review

- Academic style

- Writing for the workplace

- Spelling tips

- Writing paragraphs

- Writing sentences

- Academic word lists

- Annotated bibliographies

- Artist statement

- Case studies

- Creating effective poster presentations

- Essays, Reports, Reflective Writing

- Law assessments

- Oral presentations

- Reflective writing

- Art and design

- Critical thinking

- Maths and statistics

- Sustainability

- Educators' guide

- Learning Lab content in context

- Latest updates

- Students Alumni & Giving Staff Library

Learning Lab

Getting started at uni, study skills, referencing.

- When referencing isn't needed

- Integrating ideas

Writing and assessments

- Critical reading

- Poster presentations

- Postgraduate report writing

Subject areas

For educators.

- Educators' guide

The conclusion tells the reader what was covered.

Notice the clearly defined structure in the sample conclusion below.

Although there are many team models used in today’s organisations, to be effective, the selected team model needs to ensure both personal satisfaction and clear, shared goals. ACME Chemical’s personnel fit model showed some success in the early stages, but failed to adapt to changes in the longer term. On the other hand, BJB Minerals’ opt-in, project team model provided individual incentives as well as the broader, team benefits to achieve project success. Teams were then terminated to allow for re-formations for new and emerging goals. Effective teams do achieve significant gains for organisations and as BJB Minerals’ opt-in project model demonstrates, personal validation and achievements alongside realistic goals can be more effective on a personal and company level.

[restate argument]Although there are many team models used in today’s organisations, to be effective, the selected team model needs to ensure both personal satisfaction and clear, shared goals.[end restate argument] [sum up]ACME Chemical’s personnel fit model showed some success in the early stages, but failed to adapt to changes in the longer term. On the other hand, BJB Minerals’ opt-in, project team model provided individual incentives as well as the broader, team benefits to achieve project success. Teams were then terminated to allow for re-formations for new and emerging goals.[end sum up] [relate to big picture]Effective teams do achieve significant gains for organisations and as BJB Minerals’ opt-in project model demonstrates, personal validation and achievements alongside realistic goals can be more effective on a personal and company level.[end relate to big picture]

See the Integrating references tutorial for how to incorporate references into your writing.

- Analyse the task

- Plan and research

- Introduction

Still can't find what you need?

The RMIT University Library provides study support , one-on-one consultations and peer mentoring to RMIT students.

- Facebook (opens in a new window)

- Twitter (opens in a new window)

- Instagram (opens in a new window)

- Linkedin (opens in a new window)

- YouTube (opens in a new window)

- Weibo (opens in a new window)

- Copyright © 2024 RMIT University |

- Accessibility |

- Learning Lab feedback |

- Complaints |

- ABN 49 781 030 034 |

- CRICOS provider number: 00122A |

- RTO Code: 3046 |

- Open Universities Australia

Your Best College Essay

Maybe you love to write, or maybe you don’t. Either way, there’s a chance that the thought of writing your college essay is making you sweat. No need for nerves! We’re here to give you the important details on how to make the process as anxiety-free as possible.

What's the College Essay?

When we say “The College Essay” (capitalization for emphasis – say it out loud with the capitals and you’ll know what we mean) we’re talking about the 550-650 word essay required by most colleges and universities. Prompts for this essay can be found on the college’s website, the Common Application, or the Coalition Application. We’re not talking about the many smaller supplemental essays you might need to write in order to apply to college. Not all institutions require the essay, but most colleges and universities that are at least semi-selective do.

How do I get started?

Look for the prompts on whatever application you’re using to apply to schools (almost all of the time – with a few notable exceptions – this is the Common Application). If one of them calls out to you, awesome! You can jump right in and start to brainstorm. If none of them are giving you the right vibes, don’t worry. They’re so broad that almost anything you write can fit into one of the prompts after you’re done. Working backwards like this is totally fine and can be really useful!

What if I have writer's block?

You aren’t alone. Staring at a blank Google Doc and thinking about how this is the one chance to tell an admissions officer your story can make you freeze. Thinking about some of these questions might help you find the right topic:

- What is something about you that people have pointed out as distinctive?

- If you had to pick three words to describe yourself, what would they be? What are things you’ve done that demonstrate these qualities?

- What’s something about you that has changed over your years in high school? How or why did it change?

- What’s something you like most about yourself?

- What’s something you love so much that you lose track of the rest of the world while you do it?

If you’re still stuck on a topic, ask your family members, friends, or other trusted adults: what’s something they always think about when they think about you? What’s something they think you should be proud of? They might help you find something about yourself that you wouldn’t have surfaced on your own.

How do I grab my reader's attention?

It’s no secret that admissions officers are reading dozens – and sometimes hundreds – of essays every day. That can feel like a lot of pressure to stand out. But if you try to write the most unique essay in the world, it might end up seeming forced if it’s not genuinely you. So, what’s there to do? Our advice: start your essay with a story. Tell the reader about something you’ve done, complete with sensory details, and maybe even dialogue. Then, in the second paragraph, back up and tell us why this story is important and what it tells them about you and the theme of the essay.

THE WORD LIMIT IS SO LIMITING. HOW DO I TELL A COLLEGE MY WHOLE LIFE STORY IN 650 WORDS?

Don’t! Don’t try to tell an admissions officer about everything you’ve loved and done since you were a child. Instead, pick one or two things about yourself that you’re hoping to get across and stick to those. They’ll see the rest on the activities section of your application.

I'M STUCK ON THE CONCLUSION. HELP?

If you can’t think of another way to end the essay, talk about how the qualities you’ve discussed in your essays have prepared you for college. Try to wrap up with a sentence that refers back to the story you told in your first paragraph, if you took that route.

SHOULD I PROOFREAD MY ESSAY?

YES, proofread the essay, and have a trusted adult proofread it as well. Know that any suggestions they give you are coming from a good place, but make sure they aren’t writing your essay for you or putting it into their own voice. Admissions officers want to hear the voice of you, the applicant. Before you submit your essay anywhere, our number one advice is to read it out loud to yourself. When you read out loud you’ll catch small errors you may not have noticed before, and hear sentences that aren’t quite right.

ANY OTHER ADVICE?

Be yourself. If you’re not a naturally serious person, don’t force formality. If you’re the comedian in your friend group, go ahead and be funny. But ultimately, write as your authentic (and grammatically correct) self and trust the process.

And remember, thousands of other students your age are faced with this same essay writing task, right now. You can do it!

- IT support and systems

- RMIT Europe

- RMIT Global

- RMIT Vietnam

- Study online

- Enrol as a new student

- Before semester starts

- Orientation

- First weeks

- New research students

- Class timetables

- Important dates

- Fees, loans and payments

- Program and course information

- Assessments and results

- Research students

- Student Connect

- Study support

- My details and ID card

- Health, safety and wellbeing

- Financial and legal support

- International students

- Indigenous students

- Under 18 students

- LGBTIQ+ students

- Equitable learning and disability

- Emergency and crisis support

- Feedback, complaints and appeals

- Clubs and societies

- Events and activities

- Sport and fitness

- Creative communities

- Multi-faith chaplaincy

- Make friends at RMIT

- Accommodation

- Student rights and responsibilities

- Jobs, careers and employability

- Internships, work experience and WIL

- Scholarships

- Global experiences

- Volunteering

- Student representatives

Access RMIT IT systems, find software to use in your studies, or get tech support if you need help.

Logging in to RMIT systems

RMIT systems

Need tech help? Contact IT Connect

If you're having trouble accessing or using an RMIT system, contact IT Connect for personalised assistance.

More IT services and resources

Cyber safety

All students and staff are responsible for doing their part to protect RMIT data, systems and personal information.

Computers on campus

All RMIT Library locations have computers that students can use and book.

Printing on campus

Find out where and how to print, scan and photocopy on campus using the RMIT printing system.

Free software and apps for students

Download software for use in your studies, including Adobe Creative Cloud, Microsoft 365 and more.

Val GenAI Chatbot

Val is RMIT’s generative artificial intelligence tool. It’s like ChatGPT, but private, secure and free for RMIT students to use.

RMIT Adobe Creative Campus

Access Adobe software for free and get in-person help using it from coaches at the Adobe Hub.

Discounted devices via CompNow

Purchase discounted computers and other devices for personal use via RMIT's CompNow portal. Log in using your RMIT ID and password.

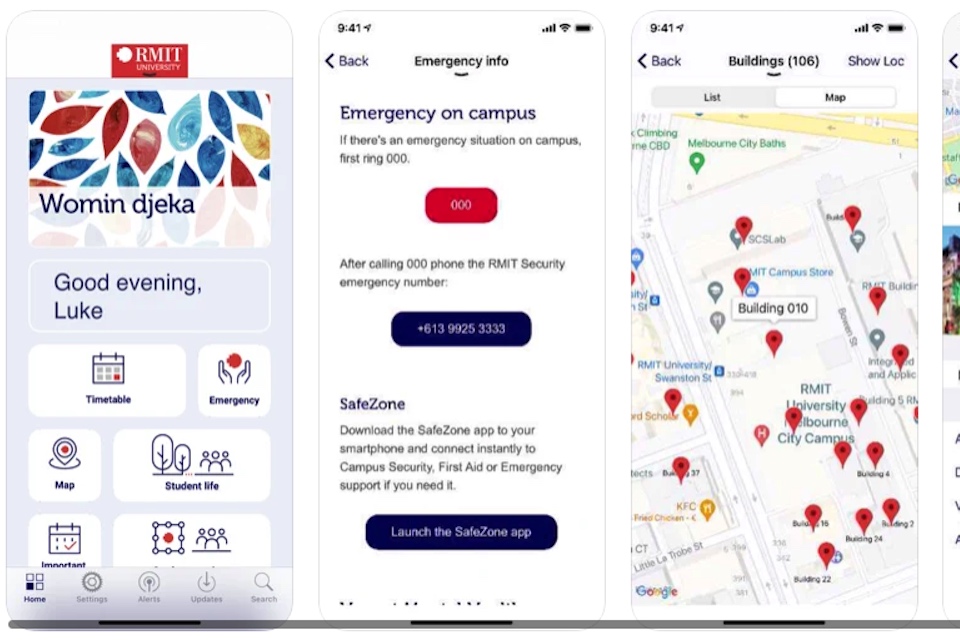

Get the RMIT App

Find all your essential student resources in one app, including class timetables, Canvas, important dates and campus maps.

IT policies and documentation

- Information Technology and Security Policy

- Acceptable Use Standard – Information Technology

- Accessibility (including IT accessibility)

- Website feedback form

- If you're having trouble accessing an RMIT system, try resetting your password via RMIT ID and password and check that you have multi-factor authentication correctly set up

- For personalised IT assistance, contact IT Connect

Acknowledgement of Country

RMIT University acknowledges the people of the Woi wurrung and Boon wurrung language groups of the eastern Kulin Nation on whose unceded lands we conduct the business of the University. RMIT University respectfully acknowledges their Ancestors and Elders, past and present. RMIT also acknowledges the Traditional Custodians and their Ancestors of the lands and waters across Australia where we conduct our business - Artwork 'Luwaytini' by Mark Cleaver, Palawa.

- Campus facilities

- Internships, work experience & WIL

- Copyright © 2024 RMIT University |

- Accessibility |

- Website feedback |

- Complaints |

- ABN 49 781 030 034 |

- CRICOS provider number: 00122A |

- RTO Code: 3046 |

- Open Universities Australia

Getting an essay writing help in less than 60 seconds

Experts to provide you writing essays service..

You can assign your order to:

- Basic writer. In this case, your paper will be completed by a standard author. It does not mean that your paper will be of poor quality. Before hiring each writer, we assess their writing skills, knowledge of the subjects, and referencing styles. Furthermore, no extra cost is required for hiring a basic writer.

- Advanced writer. If you choose this option, your order will be assigned to a proficient writer with a high satisfaction rate.

- TOP writer. If you want your order to be completed by one of the best writers from our essay writing service with superb feedback, choose this option.

- Your preferred writer. You can indicate a specific writer's ID if you have already received a paper from him/her and are satisfied with it. Also, our clients choose this option when they have a series of assignments and want every copy to be completed in one style.

receive 15% off

Eloise Braun

Advertisement

Supported by

‘Film Geek’ Review: A Cinephile’s Guide to New York

The director Richard Shepard details his lifelong obsession with movies in this enthusiastic video essay.

- Share full article

By Calum Marsh

Richard Shepard, the director of the black comedies “Dom Hemingway” and “The Matador,” is a lifelong cinephile with a voracious appetite for movies.

“Film Geek,” a feature-length video essay composed primarily of footage of films that Shepard saw growing up in the 1970s in New York City, delves deep into his obsession. In a voice-over, he recounts his childhood, when he was “addicted to movies, to watching them, to making them.” He is enthusiastic, and the movie aspires to make that enthusiasm infectious.

I appreciate Shepard’s affection: I also grew up loving movies, and I found his wistful reminiscences of being awed by “Jaws” and “Star Wars” relatable. But Shepard’s level of self-regard can be stultifying. For minutes at a time, he simply rattles off the titles of various movies that he saw as a child. I appreciate that seeing “Rocky” made a strong impression on him. I did not need to know that he lost his virginity in the apartment building where John G. Avildsen, the director of “Rocky,” once lived.

“Film Geek” has been compared to Thom Andersen’s great documentary from 2003, “Los Angeles Plays Itself,” and on the level of montage, they share a superficial resemblance: “Film Geek,” like Andersen’s essay film, is brisk and well edited.

But “Los Angeles Plays Itself” is also a thoughtful and incisive work of film criticism, whereas Shepard describes movies in clichés, when he describes movies at all. More often he is talking about himself, a subject of interest to far fewer viewers.

Film Geek Not rated. Running time: 1 hour 35 minutes. In theaters.

Explore More in TV and Movies

Not sure what to watch next we can help..

“Megalopolis,” the first film from the director Francis Ford Coppola in 13 years, premiered at the Cannes Film Festival. Here’s what to know .

Why is the “Planet of the Apes” franchise so gripping and effective? Because it doesn’t monkey around, our movie critic writes .

Luke Newton has been in the sexy Netflix hit “Bridgerton” from the start. But a new season will be his first as co-lead — or chief hunk .

There’s nothing normal about making a “Mad Max” movie, and Anya Taylor-Joy knew that when she signed on to star in “Furiosa,” the newest film in George Miller’s action series.

If you are overwhelmed by the endless options, don’t despair — we put together the best offerings on Netflix , Max , Disney+ , Amazon Prime and Hulu to make choosing your next binge a little easier.