February 3, 2021

16 min read

From Civil Rights to Black Lives Matter

Protest expert Aldon Morris explains how social justice movements succeed

By Aldon Morris

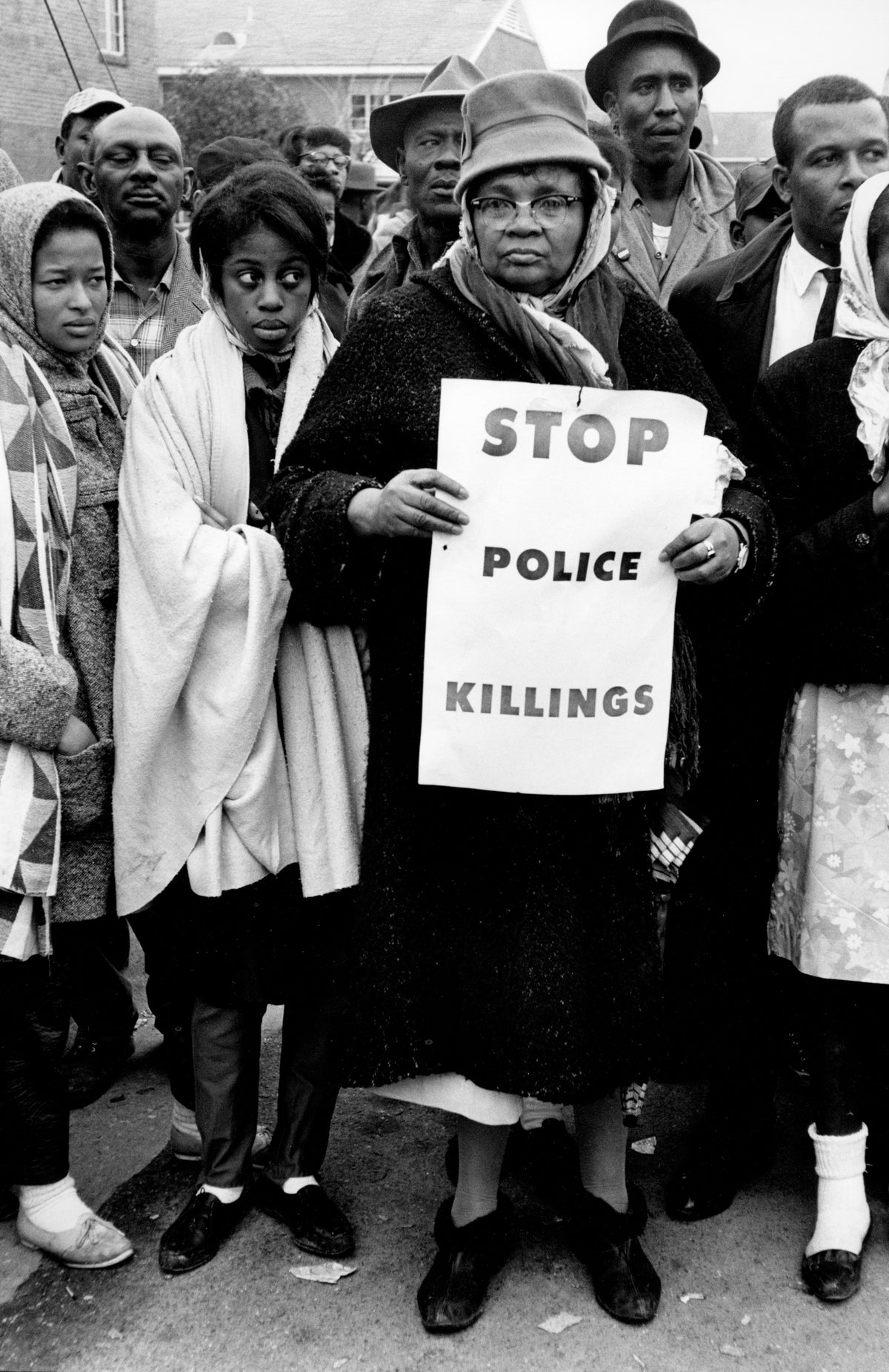

CIVIL RIGHTS supporters march from Selma to Montgomery in Alabama on March 9, 1965, in a campaign to register Black voters.

Flip Schulke Getty Images

One evening 10 years ago 17-year-old Trayvon Martin was walking through a Florida neighborhood with candy and iced tea when a vigilante pursued him and ultimately shot him dead. The killing shocked me back to the summer of 1955, when as a six-year-old boy I heard that a teenager named Emmett Till had been lynched at Money, Miss., less than 30 miles from where I lived with my grandparents. I remember the nightmares, the trying to imagine how it might feel to be battered beyond recognition and dropped into a river.

The similarities in the two assaults, almost six decades apart, were uncanny. Both youths were Black, both were visiting the communities where they were slain, and in both cases their killers were acquitted of murder. And in both cases, the anguish and outrage that Black people experienced on learning of the exonerations sparked immense and significant social movements. In December 1955, days after a meeting in her hometown of Montgomery, Ala., about the failed effort to get justice for Till, Rosa Parks refused to submit to racially segregated seating rules on a bus—igniting the Civil Rights Movement (CRM). And in July 2013, on learning about the acquittal of Martin’s killer, Alicia Garza, Patrisse Cullors and Ayọ Tometi invented the hashtag #BlackLivesMatter, a rallying cry for numerous local struggles for racial justice that sprang up across the U.S.

BLACK LIVES MATTER activists march across the George Washington Bridge in New York City on September 12, 2020, to protest systemic injustices, including the killings of Black people by police.

Credit: Jason D. Little

The Black Lives Matter (BLM) movement is still unfolding, and it is not yet clear what social and political transformations it will engender. But within a decade after Till’s murder, the social movement it detonated overthrew the brutal “Jim Crow” order in the Southern states of the U.S. Despite such spectacular achievements, contemporary scholars such as those of the Chicago School of Sociology continued to view social movements through the lens of “collective behavior theory.” Originally formulated in the late 19th century by sociologist Gabriel Tarde and psychologist Gustave Le Bon, the theory disdained social movements as crowd phenomena: ominous entities featuring rudderless mobs driven hither and thither by primitive and irrational urges.

As a member of what sociologist and activist Joyce Ladner calls the Emmett Till generation, I identify viscerally with struggles for justice and have devoted my life to studying their origins, nature, patterns and outcomes. Around the world, such movements have played pivotal roles in overthrowing slavery, colonialism, and other forms of oppression and injustice. And although the core methods by which they overcome seemingly impossible odds are now more or less understood, these struggles necessarily (and excitingly) continue to evolve faster than social scientists can comprehend them. A post-CRM generation of scholars was nonetheless able to shift the study of movements from a psychosocial approach that asked “What is wrong with the participants? Why are they acting irrationally?” to a methodological one that sought answers to questions such as “How do you launch a movement? How do you sustain it despite repression? What strategies are most likely to succeed, and why?”

Social movements have likely existed for as long as oppressive human societies have, but only in the past few centuries has their praxis—meaning, the melding of theory and practice that they involve—developed into a craft, to be learned and honed. The praxis has always been and is still being developed by the marginalized and has of necessity to be nimbler than the scholarship, which all too often serves the powerful. Key tactics have been applied, refined and shared across continents, including the boycott, which comes from the Irish struggle against British colonialism; the hunger strike, which has deep historical roots in India and Ireland and was widely used by women suffragettes in the U.K.; and nonviolent direct action, devised by Mahatma Gandhi in South Africa and India. They led to the overthrow of many unjust systems, including the global colonial order, even as collective behavior theorists continued to see social movements as irrational, spontaneous and undemocratic.

The CRM challenged these orthodoxies. To understand how extraordinary its achievements were, it is necessary to step into the past and understand how overwhelming the Jim Crow system of racial domination seemed even as late as the 1950s, when I was born. Encompassing the economic, political, legal and social spheres, it loomed over Black communities in the Southern U.S. as an unshakable edifice of white supremacy.

Jim Crow laws, named after an offensive minstrel caricature, were a collection of 19th-century state and local statutes that legalized racial segregation and relegated Black people to the bottom of the economic order. They had inherited almost nothing from the slavery era, and although they were now paid for their work, their job opportunities were largely confined to menial and manual labor. In consequence, nonwhite families earned 54 percent of the median income of white families in 1950. Black people had the formal right to vote, but the vast majority, especially in the South, were prevented from voting through various legal maneuvers and threats of violent retaliation. Black people’s lack of political power allowed their constitutional rights to be ignored—a violation codified in the 1857 “Dred Scott” decision of the Supreme Court asserting that Black people had “no rights which the white man was bound to respect.”

VOTING RIGHTS activists march 54 miles from Selma to Montgomery in 1965. The third attempt to reach Montgomery succeeded on March 25 with the protection of the federal government. The heroism and discipline of the protesters, who endured violent attacks without retaliation or retreat, enabled the passage of the Voting Rights Act that August.

Credit: Buyenlarge Getty Images

Racial segregation, which set Black people apart from the rest of humanity and labeled them as inferiors, was the linchpin of this society. Humiliation was built into our daily lives. As a child, I drank from “colored” water fountains, went around to the back of the store to buy ice cream, attended schools segregated by skin color and was handed textbooks ragged from prior use by white students. A week after classes started in the fall, almost all my classmates would vanish to pick cotton in the fields so that their families could survive. My grandparents were relatively poor, too, but after a lifetime of sharecropping they purchased a plot of land that we farmed; as a proud, independent couple, they were determined that my siblings and I study. Even they could not protect us from the fear, however: I overheard whispered conversations about Black bodies hanging from trees. Between the early 1880s and 1968 more than 3,000 Black people were lynched—hung from branches of trees; tarred, feathered and beaten by mobs; or doused with gasoline before being set ablaze. This routine terror reinforced white domination.

But by 1962, when I moved to Chicago to live with my mother, protests against Jim Crow were raging on the streets, and they thrilled me. The drama being beamed into American living rooms—I remember being glued to the television when Martin Luther King, Jr., delivered his “I Have a Dream” speech in 1963—earned the movement tens of thousands of recruits, including me. And although my attending college was something of an accident, my choice of subject in graduate school, sociology, was not. Naively believing that there were fundamental laws of social movements, I intended to master them and apply them to Black liberation movements as a participant and, I fantasized, as a leader.

As I studied collective behavior theory, however, I became outraged by its denigration of participants in social movements as fickle and unstable, bereft of legitimate grievances and under the spell of agitators. Nor did the syllabus include the pioneering works of W.E.B. Du Bois, a brilliant scholar who introduced empirical methods into sociology, produced landmark studies of inequality and Black emancipation, and co-founded the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) in 1909. I was not alone in my indignation; many other social science students of my generation, who had participated in the movements of the era, did not see their experiences reflected in the scholarship. Rejecting past orthodoxies, we began to formulate an understanding of social movements based on our lived experiences, as well as on immersive studies in the field.

Bus Boycott

In conducting my doctoral research, I followed Du Bois’s lead in trying to understand the lived experiences of the oppressed. I interviewed more than 50 architects of the CRM, including many of my childhood heroes. I found that the movement arose organically from within the Black community, which also organized, designed, funded and implemented it. It continued a centuries-long tradition of resistance to oppression that had begun on slave ships and contributed to the abolition of slavery. And it worked in tandem with more conventional approaches, such as appeals to the conscience of white elites or to the Constitution, which guaranteed equality under the law. The NAACP mounted persistent legal challenges to Jim Crow, resulting in the 1954 Supreme Court decision to desegregate schools. But little changed on the ground.

How could Black people, with their meager economic and material resources, hope to confront such an intransigent system? A long line of Black thinkers, including Frederick Douglass, Ida B. Wells and Du Bois, believed that the answer could be found in social protest. Boycotts, civil disobedience (refusal to obey unjust laws) and other direct actions, if conducted in a disciplined and nonviolent manner and on a massive scale, could effectively disrupt the society and economy, earning leverage that could be used to bargain for change. “Nonviolent direct action seeks to create such a crisis and foster such a tension that a community which has constantly refused to negotiate is forced to confront the issue. It seeks so to dramatize the issue that it can no longer be ignored,” King would explain in an open letter from the Birmingham, Ala., jail.

The reliance on nonviolence was both spiritual and strategic. It resonated with the traditions of Black churches, where the CRM was largely organized. And the spectacle of nonviolent suffering in a just cause had the potential to discomfit witnesses and render violent and intimidating reprisals less effective. In combination with disruptive protest, the sympathy and support of allies from outside the movement could cause the edifice of power to crumble.

The Montgomery bus boycott in 1955, which inaugurated the CRM, applied these tactics with flair and originality. It was far from spontaneous and unstructured. Parks and other Black commuters had been challenging bus segregation for years. After she was arrested for refusing to give up her seat, members of the Women’s Political Council, including Jo Ann Robinson, worked all night to print thousands of leaflets explaining what had happened and calling for a mass boycott of buses. They distributed the leaflets door to door, and to further spread the word, they approached local Black churches. A young minister named King, new to Montgomery, had impressed the congregation with his eloquence; labor leader E. D. Nixon and others asked him to speak for the movement. The CRM, which had begun decades earlier, flared into a full-blown struggle.

The Montgomery Improvement Association, formed by Ralph Abernathy, Nixon, Robinson, King, and others, organized the movement through a multitude of churches and associations. Workshops trained volunteers to endure insults and assaults; strategy sessions planned future rallies and programs; community leaders organized car rides to make sure some 50,000 people could get to work; and the transportation committee raised money to repair cars and buy gas. The leaders of the movement also collected funds to post bail for those arrested and assist participants who were being fired from their jobs. Music, prayers and testimonies of the personal injustices that people had experienced provided moral support and engendered solidarity, enabling the movement to withstand repression and maintain discipline.

Despite reprisals such as the bombing of King’s home, almost the entire Black community of Montgomery boycotted buses for more than a year, devastating the profits of the transport company. In 1956 the Supreme Court ruled that state bus segregation laws were unconstitutional. Although the conventional approach—a legal challenge by the NAACP—officially ended the boycott, the massive economic and social disruption it caused was decisive. Media coverage—in particular of the charismatic King—had revealed to the nation the cruelty of Jim Crow. The day after the ruling went into effect, large numbers of Black people boarded buses in Montgomery to enforce it.

This pioneering movement inspired many others across the South. In Little Rock, Ark., nine schoolchildren, acting with the support and guidance of journalist Daisy Bates, faced down threatening mobs to integrate a high school in 1957. A few years later Black college students, among them Diane Nash and the late John Lewis of Nashville, Tenn., began a series of sit-ins at “whites only” lunch counters. Recognizing the key role that students, with their idealism and their discretionary time, could play in the movement, visionary organizer Ella Baker encouraged them to form their own committee, the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee, which started to plan and execute actions independently. Escalating the challenge to Jim Crow, Black and white activists began boarding buses in the North, riding them to the South to defy bus segregation. When white mobs attacked the buses in Birmingham and the local CRM leadership, fearing casualties, sought to call off the “Freedom Rides,” Nash ensured that they continued. “We cannot let violence overcome nonviolence,” she declared.

ROSA PARKS refused to relinquish her seat to a white man on a bus in Montgomery, Ala., in December 1955, triggering the Civil Rights Movement of the 1950s and 1960s.

Credit: Underwood Archives Getty Images

The sophisticated new tactics had caught segregationists by surprise. For example, when the police jailed King in Albany, Ga., in 1961 in the hope of defeating the movement, it escalated instead: outraged by his arrest, more people joined in. To this day, no one knows who posted bail for King; many of us believe that the authorities let him go rather than deal with more protesters. The movement continually refined its tactics. In 1963 hundreds of people were being arrested in Birmingham, so CRM leaders decided to fill the jails, leaving the authorities with no means to arrest more people. In 1965 hundreds of volunteers, among them John Lewis, marched from Selma to Montgomery in Alabama to protest the suppression of Black voters and were brutally attacked by the police.

The turmoil in the U.S. was being broadcast around the world at the height of the cold war, making a mockery of the nation’s claim to representing the pinnacle of democracy. When President Lyndon B. Johnson formally ended the Jim Crow era by signing the Civil Rights Act in 1964 and the Voting Rights Act in 1965, he did so because massive protests raging in the streets had forced it. The creation of crisis-packed disruption by means of deep organization, mass mobilization, a rich church culture, and thousands of rational and emotionally energized protesters delivered the death blow to one of the world’s brutal regimes of oppression.

As I conducted my doctoral research, the first theories specific to modern social movements were beginning to emerge. In 1977 John McCarthy and Mayer Zald developed the highly influential resource mobilization theory. It argued that the mobilization of money, organization and leadership were more important than the existence of grievances in launching and sustaining movements—and marginalized peoples depended on the largesse of more affluent groups to provide these resources. In this view, the CRM was led by movement “entrepreneurs” and funded by Northern white liberals and sympathizers.

POSTER at a Selma-to-Montgomery march in 1965 protested the killings of Black people by police.

Credit: Steve Schapiro Getty Images

At roughly the same time, the late William Gamson, Charles Tilly and my graduate school classmate Doug McAdam developed political process theory. It argues that social movements are struggles for power—the power to change oppressive social conditions. Because marginalized groups cannot effectively access normal political processes such as elections, lobbying or courts, they must employ “unruly” tactics to realize their interests. As such, movements are insurgencies that engage in conflict with the authorities to pursue social change; effective organization and innovative strategy to outmaneuver repression are key to success. The theory also argues that external windows of opportunity, such as the 1954 Supreme Court decision to desegregate schools, must open for movements to succeed because they are too weak on their own.

Thus, both theories see external factors, such as well-heeled sympathizers and political opportunities, as crucial to the success of movements. My immersive interviews with CRM leaders brought me to a different view, which I conceptualized as the indigenous perspective theory. It argues that the agency of movements emanates from within oppressed communities—from their institutions, culture and creativity. Outside factors such as court rulings are important, but they are usually set in motion and implemented by the community’s actions. Movements are generated by grassroots organizers and leaders—the CRM had thousands of them in multiple centers dispersed across the South—and are products of meticulous planning and strategizing. Those who participate in them are not isolated individuals; they are embedded in social networks such as church, student or friendship circles.

Resources matter, but they come largely from within the community, at least in the early stages of a movement. Money sustains activities and protesters through prolonged repression. Secure spaces are needed where they can meet and strategize; also essential are cultural resources that can inspire heroic self-sacrifice. When facing police armed with batons and attack dogs, for example, the protesters would utter prayers or sing songs that had emerged from the struggle against slavery, bolstering courage and maintaining discipline.

MORE THAN 200,000 people participated in the March on Washington on August 28, 1963, where King articulated the aspirations of millions with his famous “I Have a Dream” speech.

Credit: Hulton Archive Getty Images

The indigenous perspective theory also frames social movements as struggles for power, which movements gain by preventing power holders from conducting economic, political and social business as usual. Tactics of disruption may range from nonviolent measures such as strikes, boycotts, sit-ins, marches and courting mass arrest to more destructive ones, including looting, urban rebellions and violence. Whichever tactics are employed, the ultimate goal is to disrupt the society sufficiently that power holders capitulate to the movement’s demands in exchange for restoration of social order.

Decades later cultural sociologists, including Jeff Goodwin, James Jasper and Francesca Polletta, challenged the earlier theories of resource mobilization and political process for ignoring culture and emotions. They pointed out that for movements to develop, a people must first see themselves as being oppressed. This awareness is far from automatic: many of those subjected to perpetual subordination come to believe their situation is natural and inevitable. This mindset precludes protest. “Too many people find themselves living amid a great period of social change, and yet they fail to develop the new attitudes, the new mental responses, that the new situation demands,” King remarked. “They end up sleeping through a revolution.” But such outlooks can be changed by organizers who make the people aware of their oppression (by informing them of their legal rights, for example, or reminding them of a time when their ancestors were free) and help them develop cultures of resistance.

Collective behavior theorists were right that emotions matter—but they had the wrong end of the stick. Injustice generates anger and righteous indignation, which organizers can summon in strategizing to address the pains of oppression. Love and empathy can be evoked to build solidarity and trust among protesters. Far from being irrational distractions, emotions, along with transformed mental attitudes, are critical to achieving social change.

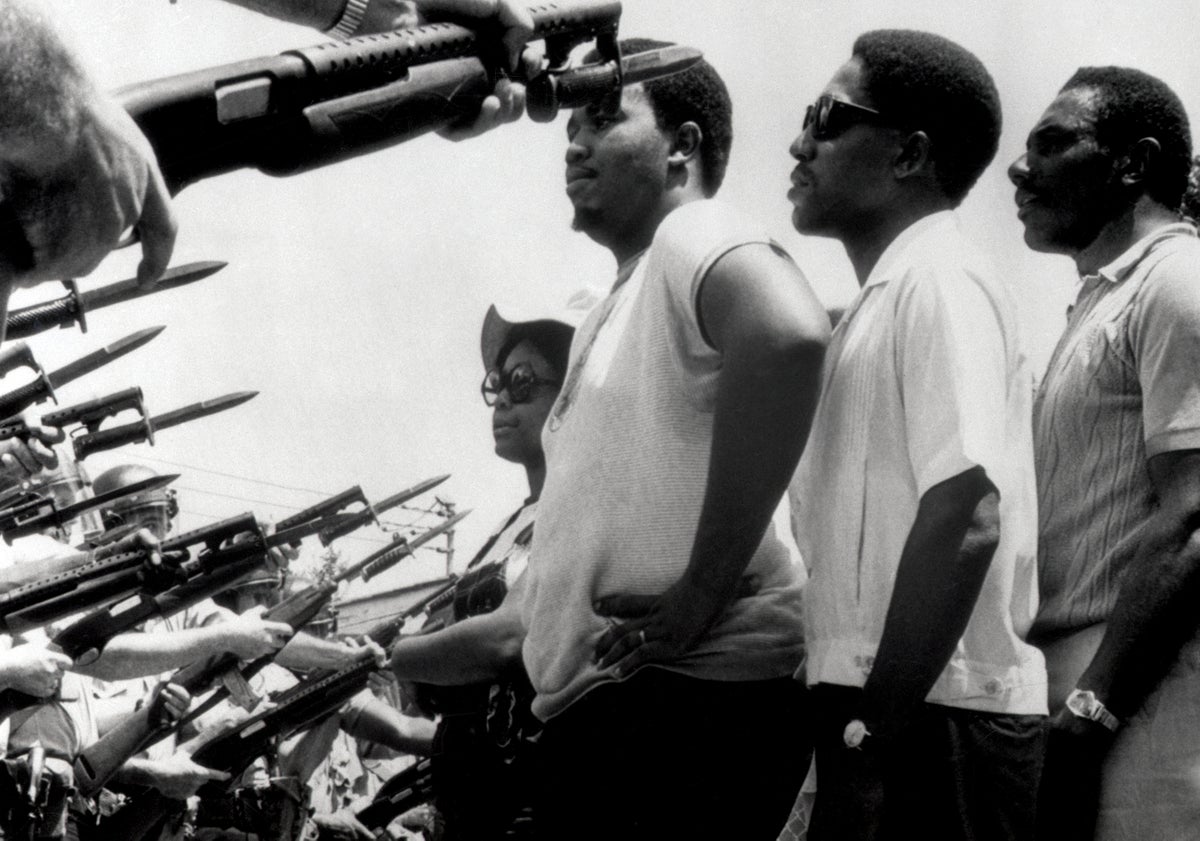

BAYONETS wielded by police officers halt unarmed protesters seeking to reach city hall in Prichard, Ala., in June 1968, months after King’s assassination in Memphis, Tenn., in April.

Credit: Bettmann Getty Images

Black Lives

On April 4, 1968, I was having “lunch” at 7 P.M. at a Chicago tavern with my colleagues—we worked the night shift at a factory that manufactured farming equipment—when the coverage was interrupted to announce that King had been assassinated. At the time, I was attracted by the Black Panthers and often discussed with friends whether King’s nonviolent methods were still relevant. But we revered him nonetheless, and the murder shocked us. When we returned to the factory, our white foremen sensed our anger and said we could go home. Riots and looting were already spreading across the U.S.

The assassination dealt a powerful blow to the CRM. It revived a long-standing debate within the Black community about the efficacy of nonviolence. If the apostle of peace could so easily be felled, how could nonviolence work? But it was just as easy to murder the advocates of self-defense and revolution. A year later the police entered a Chicago apartment at 4:30 A.M. and assassinated two leaders of the Black Panther party.

GEORGE FLOYD’S murder by a police officer in Minneapolis, Minn., on May 25, 2020, triggered the largest protests in U.S. history, including this one in New York City the following June.

Credit: Justin Aharon

A more pertinent lesson was that overreliance on one or more charismatic leaders made a movement vulnerable to decapitation. Similar assaults on leaders of social movements and centralized command structures around the world have convinced the organizers of more recent movements, such as the Occupy movement against economic inequality and BLM, to eschew centralized governance structures for loose, decentralized ones.

The triggers for both the CRM and BLM were the murders of Black people, but the rage that burst forth in sustained protest stemmed from far deeper, systemic injuries. For the CRM, the wound was racial oppression based on Jim Crow; for BLM, it is the devaluation of Black lives in all domains of American life. As scholar Keeanga-Yamahtta Taylor and others point out, when BLM was emerging, over a million Black people were behind bars, being incarcerated at more than five times the rate of white people. Black people have died at nearly three times the rate of white people during the COVID-19 pandemic, laying bare glaring disparities in health and other circumstances. And decades of austerity politics have exacerbated the already enormous wealth gap: the current net worth of a typical white family is nearly 10 times that of a Black family. For such reasons, BLM demands go far beyond the proximate one that the murders stop.

GRIEVOUS INJURIES sustained by 25-year-old Freddie Gray of Baltimore, Md., during his arrest on April 12, 2015, sparked this standoff in front of a police station. Gray died the day after the protest.

Credit: Devin Allen

The first uprisings to invoke the BLM slogan arose in the summer of 2014, following the suffocation death of Eric Garner in July—held in a police chokehold in New York City as he gasped, “I can’t breathe”—and the shooting of Michael Brown in Ferguson, Mo., in August. Tens of thousands of people protested on the streets for weeks, meeting with a militarized response that included tanks, rubber bullets and tear gas. But the killings of Black adults and children continued unabated—and with each atrocity the movement swelled. The last straw was the murder of George Floyd in May 2020 in Minneapolis, Minn., which provoked mass demonstrations in every U.S. state and in scores of countries. Millions of Americans had lost their jobs during the pandemic; they had not only the rage but also the time to express it.

By fomenting disruptions across the globe, BLM has turned racial injustice into an issue that can no longer be ignored. Modern technology facilitated its reach and speed. Gone are the days of mimeographs, which Robinson and her colleagues used to spread news of Parks’s arrest. Bystanders now document assaults on cell phones and share news and outrage worldwide almost instantaneously. Social media helps movements to mobilize people and produce international surges of protests at lightning speed.

CHANTING “Wake up, wake up! This is your fight, too!” a demonstrator summons bystanders to a Black Lives Matter protest in Brooklyn, N.Y., on June 12, 2020.

The participants in BLM are also wonderfully diverse. Most of the local CRM centers were headed by Black men. But Bayard Rustin, the movement’s most brilliant tactician, was kept in the background for fear that his homosexuality would be used to discredit its efforts. In contrast, Garza, Cullors and Tometi are all Black women, and two are queer. “Our network centers those who have been marginalized within Black liberation movements,” the mission statement of their organization, the Black Lives Matter Global Network, announces. Many white people and members of other minority groups have joined the movement, augmenting its strength.

Another key difference is centralization. Whereas the CRM was deeply embedded in Black communities and equipped with strong leaders, BLM is a loose collection of far-flung organizations. The most influential of these is the BLM network itself, with more than 40 chapters spread across the globe, each of which organizes its own actions. The movement is thus decentralized, democratic and apparently leaderless. It is a virtual “collective of liberators” who build local movements while simultaneously being part of a worldwide force that seeks to overthrow race-based police brutality and hierarchies of racial inequality and to achieve the total liberation of Black people.

What the Future Holds

Because societies are dynamic, no theory developed to explain a movement in a certain era can fully describe another one. The frameworks developed in the late 20th century remain relevant for the 21st, however. Modern movements are also struggles for power. They, too, must tackle the challenges of mobilizing resources, organizing mass participation, raising consciousness, dealing with repression and perfecting strategies of social disruption.

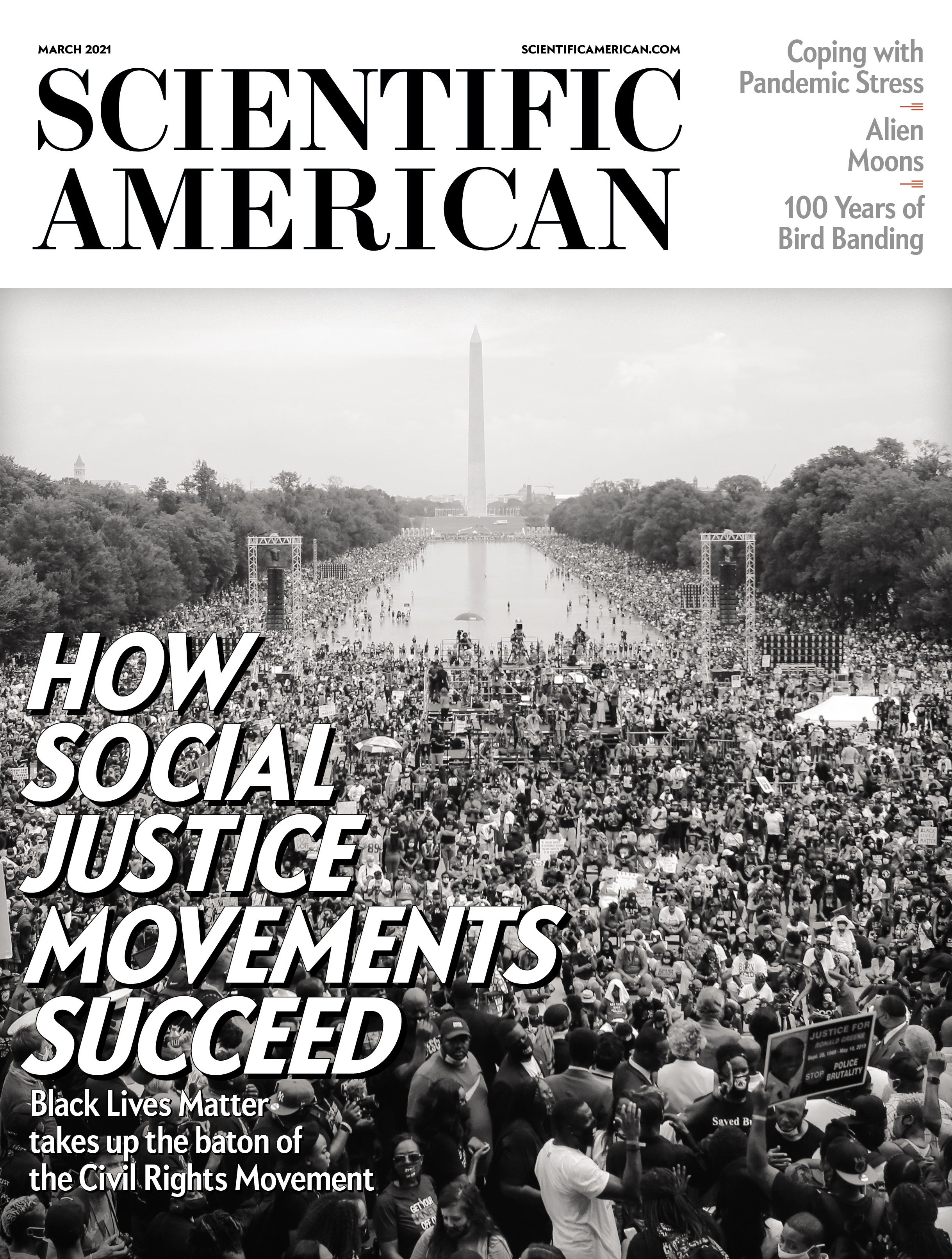

“GET YOUR KNEE OFF OUR NECKS” was the slogan for a protest at the National Mall on August 28, 2020, the 57th anniversary of the historic March on Washington led by King. The event honored the Civil Rights Movement while acknowledging the challenge of eradicating systemic racial and economic injustice in the U.S.

Credit: Joshua Rashaad McFadden

BLM faces many questions and obstacles. The CRM depended on tight-knit local communities with strong leaders, meeting in churches and other safe spaces to organize and strategize and to build solidarity and discipline. Can a decentralized movement produce the necessary solidarity as protesters face brutal repression? Will their porous Internet-based organizational structures provide secure spaces where tactics and strategies can be debated and selected? Can they maintain discipline? If protesters are not executing a planned tactic in a coordinated and disciplined manner, can they succeed? How can a movement correct a course of action that proves faulty?

Meanwhile the forces of repression are advancing. Technology benefits not only the campaigners but also their adversaries. Means of surveillance are now far more sophisticated than the wiretaps the fbi used to spy on King. Agents provocateur can turn peaceful protests into violent ones, providing the authorities with an excuse for even greater repression. How can a decentralized movement that welcomes strangers guard against such subversions?

Wherever injustice exists, struggles will arise to abolish it. Communities will continue to organize these weapons of the oppressed and will become more effective freedom fighters through trial and error. Scholars face the challenge of keeping pace with these movements as they develop. But they must do more: they need to run faster, to illuminate the paths that movements should traverse in their journeys to liberate humanity.

Aldon Morris is Leon Forrest Professor of Sociology and African American Studies at Northwestern University and a previous president of the American Sociological Association. His landmark books include The Origins of the Civil Rights Movement (1986) and The Scholar Denied: W.E.B. Du Bois and the Birth of Modern Sociology (2015).

- Articles & Journals

- Books & e-Books

- Citation Tools & Tips

- Course Reserve Materials

- Dissertations & Theses

- E-Newspapers & Magazines

- Evaluating Information

- Library Collections

- Reference Materials

- Research Guides

- Videos, Images & More

- Borrowing & Access

- View Library Account

- Computers, Printing & Scanning Services

- Accessibility Services

- Services for Undergraduate Students

- Services for Graduate Students

- Services for Distance Learners

- Services for Faculty & Staff

- Services for Alumni

- Services for Community Members

- Book A Research Appointment

- Library Presentation Student Survey

- Off Campus Access & Technical Support

- Resources for Writing

- Campus Guide to Copyright

- Teaching Support

- Gifts & Donations

- Hours & Location

- Library News

- TexShare Policy

- Strategic Plan

- {{guide_search}}

Racism & Social Injustice: Black Lives Matter

- Black Lives Matter

- Civil Rights

- Culturally Responsive Education

- Elections & Voter Suppression

- Microaggressions & Implicit Bias

- Racism & Anti-Racism

- Statistics & Data

Terminology

- Black Lives Matter Foundation, Inc. #BlackLivesMatter (BLM) was formed in 2013 in response to Zimmerman’s acquittal. This Black-centered political movement is the brainchild of three women: Alicia Garza, Patrisse Cullors, and Opal Tometi. It has grown into a global organization, the Black Lives Matter Foundation. It is based in the United States, Canada, and the United Kingdom. According to their website, their mission is to “eradicate white supremacy and build local power to intervene in violence inflicted on Black communities by the state and vigilantes.” They work to improve Black lives by stopping violent acts and advocating for Black innovation, imagination, and joy. This is done through political and ideological intervention, with a focus that also includes women, and members of the LGBTQ+ as well as all others who were not represented by other organizations. #BlackLivesMatter does not have a central structure of a hierarchy and works through local chapters. The organizations regularly hold protests to combat police brutality, inequality, racial profiling, and killings of blacks.

Books & E-books

Free E-book Download

Videos on Systemic Racism and Police Brutality

Fbi & cointelpro.

- COINTELPRO - FBI Records

- COINTELPRO 2? FBI Targets “Black Identity Extremists” Despite Surge in White Supremacist Violence

- The COINTELPRO Papers Documents from the FBI's Secret Wars Against Dissent in the United States

- FBI COINTELPRO-Black Extremism This is the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) main headquarters file on its counterintelligence program (COINTELPRO) against "black nationalist hate groups," as the FBI called them. The file begins in 1967 and ends in 1971, and consists of 26 sections of documents organized in roughly chronological order.

- FBI Intelligence Assessment - Black Identity Extremists Most Likely To Target Law Enforcement Officers (August 3, 2017)

- FBI warned of white supremacists in law enforcement 10 years ago. Has anything changed? - PBSNewsHour

- The Untold Story of COINTELPRO: Past & Present One of the foremost websites that documents the FBI's Counter Intelligence Program in America. NOTE: Internet Archive is provided as original site has been removed.

Database Subscribed Videos

- All Power to The People! Opening with a montage of four hundred years of race injustice in America, this powerful documentary provides the historical context for the establishment of the 60's civil rights movement. Rare clips of Martin Luther King, Malcolm X, Fred Hampton, and other activists transport one back to those tumultuous times. Organized by Bobby Seale and Huey P. Newton, the Black Panther Party embodied every major element of the civil rights movement which preceded it and inspired the black, brown, yellow, Native American, and women's power movements which followed. more... less... The party struck fear in the hearts of the "establishment" which viewed it as a terrorist group. Interviews with former US Attorney General Ramsey Clark, CIA officer Philip Agee, and FBI agents Wes Swearingen and Bill Turner shockingly detail a "secret domestic war" of assassination, imprisonment, and torture as the weapons of repression. Yet, the documentary is not a paean to the Panthers, for while it praises their early courage and moral idealism, it exposes their collapse due to megalomania, corruption, drugs, and narcissism.

- America After Charleston This new PBS town hall meeting, moderated by Gwen Ifill, explores the many issues around race relations that have come to the fore during this tense few months, after a white gunman shot and killed nine African-American parishioners in Charleston, South Carolina, and the removal of the Confederate flag from the state capitol grounds that followed.

- America After Ferguson This PBS town hall meeting, moderated by PBS NEWSHOUR co-anchor and managing editor Gwen Ifill, explores events following Michael Brown's death in Ferguson, Missouri. The program, recorded before an audience on the campus of the University of Missouri-St. Louis, will include national leaders and prominent thinkers in the areas of law enforcement, race and civil rights, as well as government officials, faith leaders and youth.

- Baltimore Rising - The Struggles of Police and Activists Following the Death of Freddie Gray In the wake of the 2015 death of Freddie Gray while in police custody, Baltimore was a city on the edge. Peaceful protests and destructive riots erupted in the immediate aftermath of Gray's death, reflecting the deep divisions between authorities and the community and underscoring the urgent need for reconciliation. more... less... Directed by Sonja Sohn, one of the stars of the acclaimed HBO series The Wire, BALTIMORE RISING follows activists, police officers, community leaders and gang affiliates who struggle to hold Baltimore together while the city awaits the fate of the six police officers involved in the incident. This inspiring film chronicles the determined efforts of people on all sides who fight for justice and a better city, sometimes coming together in unexpected ways and discovering a common humanity. Thought-provoking and timely, BALTIMORE RISING exposes the strife that gripped Baltimore following Freddie Gray's death, and highlights the city's determination to rise above longstanding fault lines in a distraught and damaged community.

- Context Matters: The Permanence of Racism America to Me focuses on a year at Chicago’s Oak Park and River Forest High School (OPRFHS), widely considered to be a safe, well-integrated, academically strong school. In Episode 1, we meet some of its students of color and their families, who have sacrificed to live in this popular district. Their stories begin to reveal the racial cracks and realities of the permanence of racism.

- Leadership Lessons from Black Lives Matter Rinku Sen interviews Patrisse Khan Cullors, Co-founder, Black Lives Matter; Founder and Board Member, Dignity and Power Now.

- Obama Defends Black Lives Matter Movement

- P.S. I Can't Breathe - Black Lives Matter This documentary welcomes dialogue around racial inequality, policing, and the Criminal Justice System by focusing on Eric Garners case. We hope viewers will increase their understanding of issues plaguing Black and Brown Communities by witnessing a massive group of protesters unite for the purpose of justice.

- Show Me Democracy - Student Activism Amidst the Uprising in Ferguson Amidst the uprising in Ferguson, MO, seven St. Louis college students evolve into activists as they demand change through policy and protest. This film examines their personal lives and backgrounds as each of them copes with the fallout of Ferguson. more... less... Six of the students fight for education policy reform through their internship program and try to create more opportunities for low-income and DACA students in their state. One of the seven joins the Black Lives Matter movement and organizes several protests to demonstrate against ongoing racial injustice. Following her on the ground, the camera captures several of her tension-filled protests including a night in Ferguson when the police tear gas protesters. SHOW ME DEMOCRACY asks us to examine how a committed group of college students can make a difference in a complex and imperfect system and what methods have the most impact.

- Whose Streets? An Unflinching Look at the Ferguson Uprising Told by the activists and leaders who live and breathe this movement for justice, WHOSE STREETS? is an unflinching look at the Ferguson uprising. When unarmed teenager Michael Brown is killed by police and left lying in the street for hours, it marks a breaking point for the residents of St. Louis, Missouri. Grief, long-standing racial tensions and renewed anger bring residents together to hold vigil and protest this latest tragedy. Empowered parents, artists, and teachers from around the country come together as freedom fighters. more... less... As the National Guard descends on Ferguson with military grade weaponry, these young community members become the torchbearers of a new resistance. Filmmakers Sabaah Folayan and Damon Davis know this story because they are the story. WHOSE STREETS? is a powerful battle cry from a generation fighting, not for their civil rights, but for the right to live.

Openly Accessible Videos

Watch Free Films & Documentaries on Tubi TV

BLM Articles

- Being Black Helped Me Be Blind and Being Blind Helped Me Understand that #BlackLivesMatter.

- Can You Be BLACK and Make This?

- Thoughts on Black Lives Matter and Bringing our Other Characteristics to the Table.

- Unholy Union: St. Louis Prosecutors and Police Unionize To Maintain Racist State Power

- Where Black Lives Matter Less: Understanding the Impact of Black Victims on Sentencing Outcomes in Texas Capital Murder Cases from 1973 to 2018

- Blue Lives Matter versus Black Lives Matter: Beneficial Social Policies as the Path away from Punitive Rhetoric and Harm

- 'Black Identity Extremist' or Black Dissident?: How United States v. Daniels Illustrates FBI Criminalization of Black Dissent of Law Enforcement, from COINTELPRO to Black Lives Matter

- Black Life Matters United Black Life Matters believe all lives matter. That being said, there are specifically that categorically face the African American community. Issues that can only be addressed if we, the African American people, work together to solve them.

- Black Lives Matter #BlackLivesMatter was founded in 2013 in response to the acquittal of Trayvon Martin’s murderer. Black Lives Matter Foundation, Inc is a global organization in the US, UK, and Canada, whose mission is to eradicate white supremacy and build local power to intervene in violence inflicted on Black communities by the state and vigilantes. By combating and countering acts of violence, creating space for Black imagination and innovation, and centering Black joy, we are winning immediate improvements in our lives.

- Campaign Zero Campaign Zero is an American police reform campaign proposed by activists on a website that was launched on August 21, 2015. The plan consists of ten proposals, all of which are aimed at reducing police violence.

- Color of Change Color Of Change helps you do something real about injustice. We design campaigns powerful enough to end practices that unfairly hold Black people back, and champion solutions that move us all forward. Until justice is real.

- The Movement for Black Lives (M4BL) The Movement for Black Lives (M4BL) formed in December of 2014, was created as a space for Black organizations across the country to debate and discuss the current political conditions, develop shared assessments of what political interventions were necessary in order to achieve key policy, cultural and political wins, convene organizational leadership in order to debate and co-create a shared movement wide strategy. Under the fundamental idea that we can achieve more together than we can separately.

- PBS News Hour - Black Lives Matter

- << Previous: Home

- Next: Civil Rights >>

- Last Updated: May 21, 2024 11:26 AM

- URL: https://library.untdallas.edu/racism

Contact Us:

7350 University Hills Blvd, 3rd Floor, Dallas, Texas 75241 Ph: 972-338-1616 | E-mail: [email protected] © Copyright 2024, UNT Dallas . All rights reserved.

Social Media:

Hours: Mon.-Thur.: 8:00-8:00 | Fri -Sat: 8:00-5:00 | Sun: 12:00-5:00 Directions & Maps to the Library | Privacy Statement

Black Lives Matter: race, racism, and social movements

- race, racism, and social movements

- whiteness, white supremacy, and anti-racism

- Black voices and resources for support

- anti-racism at Berklee

- The Afro-Portuguese Maritime World and the Foundations of Spanish Caribbean Society, 1570-1640 Dissertation on the foundations of the slave trade by David Wheat

- Black Girls Matter: Pushed Out, Overpoliced and Underprotected Report funded by the African American Policy Forum and Center for intersectionality and Social Policy Studies

- "The Forgotten History of How our Government Segregated the United States by the Zinn project.

- GirlTrek Black History Bootcamp A 21-day walking meditation on the activism of African American women throughout history

- Kanopy This link opens in a new window Access streaming movies, documentaries, foreign films, classic cinema, independent films, and educational videos from Berklee. New requests go through the library.

- Swank Digital Campus This link opens in a new window Please note: you will have to create an account to see the films available to Berklee. Swank provides colleges and universities with over 25,000 films, documentaries and TV shows.

- 13th (Youtube/Netflix) by Ava Duvernay

- American Son (Netflix) by Christopher Demos-Brown

- Eyes on the Prize: America's civil rights years

- "This List Of Books, Films And Podcasts About Racism Is A Start, Not A Panacea" Curated lists of books, films, and podcasts from NPR's Code Switch

- The 1619 Project From the New York Times Magazine, the project aims to reframe the country’s history by placing the consequences of slavery and the contributions of black Americans at the very center of our national narrative.

- Black Freedom Struggle This link opens in a new window This site is a curated selection of primary sources for teaching and learning about the struggles and triumphs of Black Americans. Developed with input from Black history scholars and advisors, this resource is freely available on the web and to libraries. The site will include more than 2,000 curated documents around six crucial phases of the U.S. Black freedom struggle. Each time period features an overview plus organized information and links to primary source documents about the relevant people, places, related government documents.

- Their Eyes on the Prize: resources on segregation in education Resources curated by Facing History and Ourselves, an organization that uses the lessons of history to challenge teachers and their students to stand up to bigotry and hate.

Berklee Resources

- Berklee's Commitment to Inclusion Statement

- Berklee Center for Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion (CDEI)

- Berklee CDEI's list of "Books and Speeches by Black Scholars, Activists, and Change Agents"

- Antiracist resources from the Berklee Institute of Jazz and Gender Justice

- Health & Wellness

- Ask a Librarian

- Diversity and Inclusion Collection by Stacey Snyder Last Updated Jun 12, 2024 48 views this year

- Jazz and Gender Justice by Judith S. Pinnolis Last Updated Jun 12, 2024 355 views this year

- Black History Month by Stacey Snyder Last Updated Jun 12, 2024 306 views this year

- << Previous: home

- Next: whiteness, white supremacy, and anti-racism >>

- Last Updated: Jun 12, 2024 1:52 PM

- URL: https://guides.library.berklee.edu/blm

Find anything you save across the site in your account

Has Black Lives Matter Changed the World?

By Jay Caspian Kang

How should we think about the Black Lives Matter movement, now that three years have passed since the worldwide George Floyd protests? In sympathetic circles, the question does not usually inspire a direct answer, but, rather, a seemingly endless set of caveats and follow-up questions. What constitutes success? What changes could possibly be expected in such a short period of time? Are we talking about actual policies or are we talking about changed minds? I’ve engaged in this type of back-and-forth on several occasions during the past few years, and, though I believe the protests were, on balance, a force for good in this country, I wonder whether all this chin-scratching suggests a lack of conviction. Why don’t we have a clearer answer?

In his new book, “ After Black Lives Matter ,” the political scientist Cedric Johnson blows right past the sort of hemming and hawing that has become de rigueur in today’s conversations about the George Floyd protests. Johnson chooses, instead, to level a provocative and expansive critique from the left of the loose collection of protest actions, organizations, and ideological movements—whether prison abolition or calls to defund the police —that make up what we now call Black Lives Matter . He agrees that unchecked police power is a societal ill that should inspire vigorous dissent. His problem is more with the “Black Lives Matter” part—not the assertion, itself, which should be self-evident, but, rather, how the shaping of the slogan and its main beneficiaries (Johnson believes these are mostly corporate entities) promoted a totalizing and obscurantist vision of race and power.

Much like Barbara Fields and Adolph Reed , two Black scholars cited in the book, Johnson is a socialist, and his argument is “inspired and informed by the left-wing of antipolicing struggles,” which he takes great care to distinguish from what he sees as the more corporatized and popular vision of Black Lives Matter, and the naïvete of the police-abolition movement. He does not dismiss the pernicious impact that racism has upon the lives of people in this country, but he does not see much potential in a movement that focusses on race alone, nor does he believe that it accurately assesses the problem with policing. He writes:

During the 2020 George Floyd protests, the politics of Black Lives Matter seemed especially militant and stood in sharp contrast to the pro-policing, authoritarian posturing and hubris of the Trump administration. The fundamental BLM demand, that black lives equally deserve protections guaranteed under the Constitution, momentarily achieved majority-national support. Through slogans like the “New Jim Crow” and “Black Lives Matter,” the problem of expansive carceral power was codified as a uniquely black predicament. Police violence, however, is not meted out against the black population en masse but is trained on the most dispossessed segments of the working class across metropolitan, small town and rural geographies.

The police , in other words, enact violence against all poor people, because, in a capitalist country like the United States, the police serve primarily to reproduce “the market economy, processes of real estate development in central cities and the management of surplus populations.” Poor rural whites, Black people who live in the inner cities, Latinos in depressed agricultural districts, and Native Americans across the country can all be tagged as surplus, and Johnson argues that this condition has a much more direct and meaningful impact on how they are policed than race does. He also believes that the focus on race serves bourgeois interests, because it reduces the question of inequality in this country to skin color; this, in turn, obviates any discussion about how an improvement in basic living standards —health care, housing, child care, and education—could make communities safer. If all you have to do is expunge the racism in the hearts of police officers, or, perhaps, just reduce the number of racist patrol officers on the streets, you don’t have to do much about poverty. Or, at the very least, you can pretend that class conflict and racialized police brutality are two separate issues, when, in fact, they are the same thing.

“After Black Lives Matter” should be commended both for the clarity of its message and the bravery of its convictions. Even among scholars on the left who are critical of identity politics, there’s a wide range of responses to popular works such as “ The 1619 Project ”or Ibram X. Kendi ’s Antiracist series , which seem to focus on race above all other things. Some, like Olúfẹ́mi O. Táíwò , level a more capacious critique of identity politics, even in its most crass and capitalistic forms: though Táíwò may object to the approach and analyses of so-called identitarians, he still sees them as his teammates. Others, like Fields and Reed, are far more dismissive. Johnson certainly falls in this second camp. He rails against “wokelords,” who are keen to shame and confront anyone who may offer up a critique of identity politics; he believes that modern racial-justice discourse “prompts liberal solutions, such as implicit bias training, body cameras, hiring more black police officers and administrators,” which, in turn, “erects unnecessary barriers between would-be allies.”

Johnson argues that, although Black Lives Matter may have dressed itself up in revolutionary clothing, it ultimately still followed the differential logic of a corporate diversity training: one group of people is asked to acknowledge another and fixate on points of difference. “BLM discourse truncates the policing problem as one of endemic antiblackness, and cuts off potential constituencies,” he writes, “treating other communities who have suffered police abuse and citizens who are deeply committed to achieving social justice as merely allies, junior partners rather than political equals and comrades.”

What emerges from “After Black Lives Matter” is a type of pragmatism, one that looks to build solidarity across racial lines. White people, especially poor white people, are also killed by the police, as are poor Latinos and poor Asians. Any change—whether revolutionary, legislative, or reformative—will require a critical mass of people who feel that their own interests are at stake in an anti-policing movement. Black Lives Matter, Johnson argues, may have been effective in getting people out on the streets because of its manipulation of digital platforms, but it also had wide appeal because it did not truly challenge the capitalist, neoliberal order. The reason so many corporations, for example, were so quick to offer funds for Black creators or anti-racism efforts wasn’t that they felt intimidated by what was happening in the streets, but because they saw a shift in how the country felt about race and quickly moved to adjust their optics without touching the underlying exploitative practices. In the summer of 2020, oil companies, multinational banks, the C.I.A., the N.F.L. all came out with commitments to Black Lives Matter. Johnson sees this as “an instance of ideological convergence—between the militant racial liberalism of Black Lives Matter and the operational racial liberalism of the investor class.” A truly transformative movement, then, would be broad and inclusive in its messaging, and also radical in its critique and democratic in its methods.

Johnson’s pragmatism also extends to the debates around defunding or abolishing the police. He reminds the reader that, at certain points in American history, “state coercion was necessary to secure racial justice.” Desegregation, for example, required the support of federal marshals and National Guardsmen, even if it also was opposed, violently, by the local law enforcement. Johnson advocates, instead, to “right-size” and “demilitarize” the police, but argues that “it seems rather naive to think that a complex, populous urban society can exist without any law enforcement at all, especially in those moments when forces threaten social justice and even the basic democratic rights of citizens.”

Johnson’s own prescription is to “abolish the class conditions that modern policing has come to manage.” He argues that any real change to policing will not come from a “mass rejection of racism,” but instead a “shared vision of the good society.” Eliminating racism, Johnson concedes, is a worthwhile goal, but the essentialist vision of race and the way that it narrows down the conversation about change in society down to one group—namely, Black Americans—will always be limited to the oppressed-and-ally relationship, which creates barriers instead of searching for common grievances. The alternative, Johnson argues, is “broadly redistributive left politics centered on public goods” that would ultimately allow for “powerful coalitions built on shared self-interests” to emerge.

I am sympathetic to Johnson’s critique, not only because I also see the limits of identity politics but also because I have seen the needlessly divisive and dispiriting ideology of racial essentialism in action at protests around the country. I’ve written about many of these instances in the past, whether the “wall of white allies” I saw in Minnesota or the harsh reprimand a white protester received from a Black organizer for daring to talk to a reporter. (Her offense, as far as I could tell, wasn’t speaking to the press, but, rather, “centering herself.”) These types of instances, which weren’t exactly common, but did recur during my years of reporting on protests, may have been interesting on an intellectual level—seeing theory in action is always a bit thrilling. But they also convinced me that not much action could come from a movement that endlessly polices its own “allies.” I do not think people stay allies for very long, but I do believe that they act in their self-interests for a lifetime. Therefore, if one is committed to profoundly changing policing, the work will require convincing as many people as possible that they, too, can be abused and killed by the police.

But there’s also a profound contradiction that I haven’t quite been able to square in my own head, and perhaps never will. Johnson is correct in saying that Black Lives Matter, by explicit design, elevated the concerns of Black people over those of others who may have been targeted by the police. But it was this message, and not a broader anti-capitalist critique, which has captivated millions of people for almost a decade now. This message was the one that ultimately resonated, not only in the United States but also in protests around the world.

There were people I saw in every march I attended, from Ferguson to the Floyd protests, who truly did believe that they were doing revolutionary work in the name of Black Lives Matter. In the summer of 2020, I saw nervous first-timers who had no love for corporate remediations on race and were ready to leave their homes and march out into the streets. It is the job of scholars and critics, like Johnson and me, to think about what it all might have meant, yet I don’t think it’s really possible to take an event as large as the summer of 2020 and make such a broad, declarative assessment of the political motivations behind all of it.

Early in the book, Johnson makes the distinction between organized power and mass mobilization. The sheer size and diversity of the Floyd protests pointed to the latter—something he says is “much easier now with the endless opportunities for expressing discontent provided by social media, online petitions, memes and vlogging.” In describing the difference, Johnson is asking the profound political question of the past twenty years: Does the ephemeral nature of social media dilute the power of street protest? Does it turn everything into online symbology , and give the people who show up a false sense that they have accomplished something real?

I wonder, perhaps naïvely, whether we simply need more time to accurately gauge the gains of the summer of 2020. A group of unpopular activists was able to overturn Roe v. Wade after fifty years of planning and organizing. The actual mechanisms for change may have wound through the courts, but anti-abortion activists still had to create the circumstances, whether by influencing conservative legal scholars, fostering their own like Amy Coney Barrett, or even just keeping things together through decades of opposition.

On the left, social movements find their inspiration and fuel from protests, and it’s worth giving credit where it’s due: if not for Black Lives Matter, millions of people might not have explicitly come out into the streets of America to protest the conditions that give rise to police violence. And the demonstrations of 2020 also gave rise to other forms of solidarity. Under the banner of the George Floyd protests, many labor unions, including the Oakland chapter of the International Longshore and Warehouse Union, staged their own actions. These exposed attendees to the differences between working-class solidarity and the types of neoliberal identity politics that only ask for small reforms that do not challenge wealth inequality or even the criminal-justice system in any profound way. Perhaps there is a way to excise the bad part of these mass protests from the good, and still maintain a mass presence on the streets. But, if there is, I have yet to see it in action. ♦

New Yorker Favorites

Summer in the city in the days before air-conditioning .

My childhood in a cult .

How Apollo 13 got lost on its way to the moon— then made it back .

Notes from the Comma Queen: “who” or “whom”?

The surreal case of a C.I.A. hacker’s revenge .

Fiction by Edward P. Jones: “Bad Neighbors”

Support The New Yorker’s award-winning journalism. Subscribe today .

By signing up, you agree to our User Agreement and Privacy Policy & Cookie Statement . This site is protected by reCAPTCHA and the Google Privacy Policy and Terms of Service apply.

By Eyal Press

By Ian Buruma

By Susan B. Glasser

By Daniel Immerwahr

Remembering why Black Lives Matter with Alicia Garza: podcast and transcript

“Black people. I love you. I love us. Our lives matter.” In July of 2013, Alicia Garza wrote these words in reaction to a jury’s acquittal of George Zimmerman in the shooting death of Trayvon Martin. That post turned into a hashtag which became the rallying cry for one of the most recognizable social movements of this generation.

While it can feel like the nation’s current racial discourse is trending downward, the last four or five years have seen an ostensible, rapid expansion of social justice consciousness with public opinion polling showing racial attitudes moving in the right direction. Black Lives Matter was an enormous part of catalyzing these public opinion changes and reform movements. Alicia Garza is at the center of it all and joins us to shed light on the origins of #BlackLivesMatter and how it’s evolved in the years since.

ALICIA GARZA: One of the things that we are really trying to get across is that black people are not a monolith. We are LGBT, we are urban and rural, we are liberal and conservative and the candidate and the campaign that is going to energize us the most is going to act like they know something about us and it's going to go beyond fried chicken and hot sauce.

CHRIS HAYES: Hello and welcome to "Why Is This Happening?" with me, your host Chris Hayes. So there's this term that I started seeing online that people have been writing about the era we're in and it's a tongue-in-cheek term that I think is basically sort of derisive, but kind of in a comical way and it's the “Great Awokening.” You've maybe heard this term, the Great Awokening. And it's a reference to the great awakening, which were at least two different periods of incredible religious fervor that spread through the United States in both the 18th and 19th centuries and you know, really shaped a lot about American spirituality, religion and politics.

It led to the creation of different Christian traditions and new religions and it changed public opinion. It also, you know, provided the seeds for what would become the abolition movement, right? So this real transformation in people's consciousness, the way they thought about their relationship to each other and to God and then that became a social force that ended up in abolition.

The Great Awokening, which is again, a kind of tongue-in-cheek term, is about a sort of social justice consciousness explosion that's happened in this country I would say in the last four or five years, and I think particularly among a certain segment or sector of white people. And that's why I think the kind of Awokening teasingness is embedded in that term, right? That certain kind of person, a white person who is sort of finding a kind of racial consciousness about the nature of white supremacy, the nature of racial hierarchy, the nature of racial exclusion for people of color, the history of the country in that respect.

But I actually, I am kind of a defender of the Great Awokening. I think that one of the crazy paradoxes of our time is that there are two things happening simultaneously, and it's really hard to kind of keep them both in your head. There is a white ethno-nationalist backlash in the country's politics. There is increasingly loud out and proud avowed white supremacists, Nazis, people in the public sphere advocating for blood and soil ethno-nationalism.

There is a president in the White House who is an obvious bigot and racist and says racist and bigoted things and doesn't back down from saying racist and bigoted things and has given permission to other politicians and to other ones of his followers to be outwardly bigoted and racist about black people, about Muslims, about all sorts of different groups.

And at some level, it feels like it's as worse as it's ever been in terms of the country's racial discourse. Well, that's obviously not true. It's as worse as it's been in my lifetime or my adult lifetime in terms of the country's racial discourse and the presence of outwardly white supremacist bigoted ideas about what America should be, that it should be essentially a white man's republic which is lurking all around the Trump administration everywhere you look, right?

The positions they take, the fact they're trying to rig the census explicitly to help white people get more power. The way they talk about immigrants and not just unauthorized immigrants, but legal immigrants, too. The kind of demographic dilution, the idea that there's this great replacement happening which is this really vile white nationalist idea that behind the curtain, Jews like George Soros are paying people to flood the country with non-white folks so that white people won't make a majority. All this stuff is really dangerous, vile, disgusting and right out there.

You can turn on Trump TV and you can hear this kind of stuff. So that's one part of our racial discourse. The other part of our racial discourse is that racial attitudes in public opinion data after public opinion data are getting much better. People are more pro-immigrant now than they have been at any time in recent memory, partly, I think, as response in backlash to what Trump and Trumpism means. Appreciations and perceptions of the challenges that African Americans face, particularly because of structural racism and white supremacy by white people is getting much, much better.

Now if you dig into the data, there are huge, huge differences internally like education level and generationally, right? Young white folks with college degrees are much more likely to answer affirmatively that there are structural impediments to black advancement that are the product of white supremacy and structural racism than say a 65-year-old white person with a high school degree.

All that said, the public opinion is moving in the right direction and also, the politics of a lot of the issues on the ground around race are moving in the right direction. You see these victories. You see a city like Philadelphia elect a public defender to be the chief prosecutor, running explicitly on an agenda of completely overhauling the way we conceive of our prosecutors office, Larry Krasner, who we had on the podcast.

You see in Florida almost a two-thirds majority voting to give felons who have completed their sentence the right to vote. You see reform candidates all over the place across the country winning election on ending cash bail. All of this is stuff that the politics of which has always been intensely racially coded and in the years of the '80s and '90s particularly was used as a kind of form to demagogue on race, right? We're going to throw people in jail and lock away the key. And I lived it firsthand in New York City and I wrote a book about that experience called A Colony in A Nation.

And in many, many ways, public opinion and the politics of those issues are better now, much improved. So that’s the paradox of the moment about America's racial politics this moment. We're super polarized. The most vile kinds of thoughts about racial essentialism and racism and white supremacy are more available than they've ever been and in some ways more empowered than they've ever been. And at the same time, public opinion is moving in the right direction and there are all these local victories.

And it's hard to make sense of how this is the case, but I think you can't tell the story of where we are without talking about the movement for black lives and Black Lives Matter. Because Black Lives Matter beginning in 2013, which was the trial of George Zimmerman for killing teenager and Florida native Trayvon Martin. That phrase and the movement that built up around it, about the deaths of black people at the hands of either white assailants or police officers or the State in some way.

That movement was an enormous part of catalyzing the public opinion changes we've seen, an enormous part of catalyzing the reform movements we've seen. And yet the movement itself feels way less present in the everyday of Trump's America than it did five years ago. The amount of cable news stories about a black man dead at the hands of police is much lower. The amount of demonstrations you see in the wake of that, right?

There was a period of time in which that was so dominant in the news and in consciousness and the dominance of that in the news and the consciousness has gone away, but also, in the wake of it has transformed into really profound and I think amazing changes in American racial attitudes.

So I wanted to talk to someone who's been at the center of this trajectory about where we are right now. Her name is Alicia Garza. She is the co-creator of Black Lives Matter Global Network. She is a principal of this really cool organization called Black Futures Lab, which is a kind of think tank that's trying to think about different ways of imagining the future for black people in America. And she's the director of strategy and partnerships of the National Domestic Worker's Alliance. And you have probably read about her or seen her.

She is just incredibly compelling and dynamic force. If you ever see her speak, you will remember. You will write down her name. You will remember her. You will remember the way that she talks. She was the person that wrote the phrase Black Lives Matter in this impassioned Facebook post in the wake of the acquittal of George Zimmerman for Trayvon Martin's death. She's an organizer and an activist. And you'll hear in this conversation she's got incredible wisdom and first-hand experience in how you build movements and sustain movements for social justice.

And she also has a feature ... I was talking to Tiffany about this. She has something that I'm finding more and more is a kind of a common thread in a lot of people we interview here on #WITHpod and that I find interesting which is that we like to think of American life as very fluid and mobile, that people can begin at any station, rise very high and we don't have these huge barriers. But the reality of it is it's often not that way. It's often like the deck of the Titanic.

People are consigned to different parts of an experience. And something that Alicia has is life experience in many different worlds of American life and experience of being a person who was the other, who was different than the world that she was living in, which you'll hear her talking about. And I think that imbues her, and it imbues a lot of the other people that we talked to on the podcast with this kind of perspective. This almost sort of form of moral prophecy that comes from experiencing yourself in relation to others in this very sort of distinct way.

And so you can hear her talk about how she found her way through her upbringing, through her life experience to the work that she's done and crucially, where we are right now in this moment. How do you think about the paradox between Donald Trump and the White House, white nationalism and ethno-nationalism on the march globally and the movement for black equality and true, genuine, egalitarian multiracial democracy in the 21st century.

You've been on my radar screen for years now and I just thought maybe I'd talk a little bit about your upbringing. You're from the Bay Area, right?

ALICIA GARZA: Born and raised.

CHRIS HAYES: Born and raised. What was your upbringing like and where did you sort of start to get your political consciousness?

ALICIA GARZA: You know, I was born and raised in the Bay Area, lived in San Rafael, California, represent, and then moved to Tiburon and people always at this point go, "Oh, Tiburon." This very swanky place. And yes, I was one of the only black people who lived there for anybody who's asking. I grew up the product ... My mom, she was incredible. She passed away a year ago.

CHRIS HAYES: I’m sorry.

ALICIA GARZA: It's okay. Thank you. She was kind of a jack of all trades and could do everything and anything. But I wouldn't say that my mom or my parents were political at all. I mean in some ways, they lived kind of a political life. They were an interracial couple and so I think you get to avoid politics when you're, you know, challenging them by your very existence.

CHRIS HAYES: Totally.

ALICIA GARZA: But I wouldn't say that they were necessarily political.

CHRIS HAYES: They were not activists. They were not ...

ALICIA GARZA: No.

CHRIS HAYES: It was not dinner table fights on the news.

ALICIA GARZA: Not at all. Not at all. They weren't encouraging me to go to marches and things like that, you know. I'm not a red diaper baby. I actually got politicized at the age of 12. There was a fight happening in my school district about whether or not to offer contraception in school nurses' offices. And my mom, you know, had me as a single mother. And she didn't expect to have me and so she had to figure it out. And from a very, very young age, she talked to me about sex and the real story. She wasn't there's a stork and you know, I didn't get any of that.

It was sex makes babies, babies are expensive and that's the end of the story. So when it came to being able to provide tools for people to be able to determine what they wanted their life to look like, when and if they wanted to start and have families, it seemed like a no-brainer for me, but it was certainly a big deal.

CHRIS HAYES: So was the fight about the accessibility or the availability of contraceptives in the school?

ALICIA GARZA: Yes. Absolutely. And, of course, this was during the Bush era, the first Bush, where you know, there was "Focus On The Family" and there was a huge fight happening nationally, actually, about abstinence only education in schools and then comprehensive sex health ed. And I was right in the middle of that.

CHRIS HAYES: So you became an activist at 12.

ALICIA GARZA: Very much so.

CHRIS HAYES: For the availability of contraceptives in your school.

ALICIA GARZA: Absolutely.

CHRIS HAYES: And did that sort of awaken that kind of part of you?

ALICIA GARZA: It did. It did. I really enjoyed not only kind of uncovering truth, how I thought about it, but also really thought it was important that people had the information that they needed to make decisions that were right for them and been going ever since.

CHRIS HAYES: So what was it like? You said you were one of the few black people where you were growing up.

ALICIA GARZA: Literally one of the few.

CHRIS HAYES: And your parents were a mixed-race marriage. How do you think that sort of formed your consciousness, your perception?

ALICIA GARZA: Well, in a lot of ways, it made me really conscious of being different.

CHRIS HAYES: I can imagine.

ALICIA GARZA: So conscious of being different. And you know, I mean, in the town that I grew up in, you know, which is relatively liberal, right, compared to most places, I remember that my mom would get pulled over in my town and she would have to call my dad to come and pick her up and vouch for her.

CHRIS HAYES: Vouch.

ALICIA GARZA: Because literally, the police in this very small community didn't believe that this woman who's driving a Mercedes or whatever she was driving at the time actually lived there, that the car was hers. And my parents lived in that community for about 25 years.

CHRIS HAYES: And that would happen with you in the car.

ALICIA GARZA: Totally. It would happen with me in the car. That would happen without me in the car. You know, it's very common.

CHRIS HAYES: You know, a thing I think about a lot. I think about how tall people, I think particularly tall women who get tall very early, they tend to slouch, right?

ALICIA GARZA: Yeah.

CHRIS HAYES: And it's protective, but it always strikes me that there's this incredible thing that's happening which is that your perception of the world and the way that you move through the world and stick out in it is actually having the subconscious effect on your spine, right?

CHRIS HAYES: And it's I think about that a lot in the context of different kinds of difference, whether that's disability or race. That's doing some work way below whatever is in the prefrontal cortex.

ALICIA GARZA: That's right.

CHRIS HAYES: That's all the way down through the cells, moving through that world.

ALICIA GARZA: That's right and being very conscious of the fact that you're always being watched and having to kind of get comfortable in that. And I think when I was younger, I was very uncomfortable with it. I really wanted to blend in. But there was no possible way for me to do that, literally no possible way. And so it forced me to get comfortable really early with not only being okay with being different, but being okay in my own skin.

CHRIS HAYES: Was the move toward activism when you're 12, which is young, do you remember that as part of that kind of processing of that difference or something? Like claiming it in some way, right? If you're the focus of attention, you have agency over that, over the eyeballs, right, if you're putting yourself out there.

ALICIA GARZA: Mm-hmm. Yeah. I don't remember. I mean what I know is that I loved talking to my peers about sex and desire and intimacy and also, you know.

CHRIS HAYES: You're not from a Catholic household.

ALICIA GARZA: No. Definitely not. Definitely not.

CHRIS HAYES: I love talking to my peers about sex and intimacy. Yeah.

ALICIA GARZA: I did. And I was even having sex at the time.

CHRIS HAYES: That's totally my upbringing.

ALICIA GARZA: Which is even funnier. But you know, I mean part of it is I do think that what felt important to me was that women like my mother could have the choice as to whether or not they wanted to have a me. My mom had me at what was relatively a young age. I mean she was in her mid-to-late 20s when she had me and I'm in my late 30s and I cannot imagine.

I don't have kids yet and I'm still ... You know, I twitch at the idea. So think about this woman who's, you know, 28 years old and she's trying to figure out what she's going to do. Her whole life is changing in front of her eyes and had my mom been in a state, for example, where abortions were banned or birth control was limited, she would not have the same range of choices that she had with me. And I think that everybody should be able to have the same range of choices. And that's what really drove me.