We Need to Talk About Books

Heart of darkness by joseph conrad [a review].

Four men aboard a yacht on the eastern Thames anchor for the night. The men are pensive, contemplative, in no mood for talk or games. But, somewhat expectedly, one of the men – Marlow – has a tale he wants to share.

Marlow tells them how, as a young man, he had a strong desire for adventure, for seeking out the edges of the known world, and had always felt certain perilous temptation when looking upon the serpentine shape of the Congo as it looks on a map.

Going up that river was like travelling back to the earliest beginnings of the world, when vegetation rioted on the earth and the big trees were kings. An empty stream, a great silence, an impenetrable forest.

Marlow manages to get a job as a steamboat captain, replacing a man who was killed in an argument with natives. Arriving on the African coast, meeting with the company accountant, Marlow first hears of Kurtz; a name that will obsess him during his short time in Africa. Kurtz is a notorious agent for the company. He sends downriver as much ivory as all the other agents combined and an aura of mystery and expectation surrounds him. His success has won him great admiration and jealous enemies.

The point was in his being a gifted creature, and that of all his gifts the one that stood out pre-eminently, that carried with it a sense of real presence, was his ability to talk, his words – the gift of expression, the bewildering, the illuminating, the most exalted and most contemptible, the pulsating stream of light, or the deceitful flow from the heart of an impenetrable darkness.

But Marlow has plenty to deal with of his own. First there is a 200-mile trek inland to reach the central station. Arriving, he finds that the ship he is meant to captain has sunk and it may take months to fish it out and repair it. They need to work fast; the stations upriver and deeper inland rely heavily on regular supplies from the central station. And Kurtz is said to be ill, his station in jeopardy.

Marlow finds himself rapidly becoming obsessed with this enigmatic figure. He desperately hopes to find Kurtz alive and to listen to what he has to say.

Heart of Darkness has a great opening. The writing is very pretty and the story is immediately evocative and transporting. You instantly feel as if you are one of those aboard the yacht, listening to the old seaman telling his tale.

One ship is very much like another, and the sea is always the same. In the immutability of their surroundings the foreign shores, the foreign faces, the changing immensity of life, glide past, veiled not by a sense of mystery but by a slightly disdainful ignorance; for there is nothing mysterious to a seaman unless it be the sea itself, which is the mistress of his existence and as inscrutable as Destiny.

Once Conrad has put you at ease in this relaxed setting he lets Marlow’s story unsettle you with its sense of danger, mystery and ultimately, horror.

Racism, colonialism and imperialism appear to be key themes of the novel. Owen Knowles, who contributed the introduction to this Penguin Classics edition seems to agree. At the time of writing, in the late nineteenth century, European powers were in a scramble to systematically annex and exploit Africa, just as there had been earlier scrambles for the Americas, India and China. As in the previous cases, the argument that the European has a moral duty to ‘civilise’ the non-European served to both disguise and justify the exploitation. Stories about the crimes of exploitation were just beginning to filter through to the public. One interpretation of the novel is that Conrad, via Marlow, is speaking out. Within a few years of the publication of Heart of Darkness (1899) came the Boer War and the Atrocities in the Congo Free State and a noticeable shift in European attitudes.

They were no colonists; their administration was merely a squeeze, and nothing more, I suspect. They were conquerors, and for that you want only brute force – nothing to boast of, when you have it, since your strength is just an accident arising from the weakness of others. They grabbed what they could get and for the sake of what was to be got. It was just robbery with violence, aggravated murder on a great scale, and men going at it blind – as is very proper for those who tackle a darkness. The conquest of the earth, which mostly means the taking it away from those who have a different complexion or slightly flatter noses than ourselves, it is not a pretty thing when you look into it too much.

That being said, Marlow is not immune to the prejudices that were pervasive to his culture and time.

And between the whiles I had to look after the savage who was fireman. He was an improved specimen; he could fire up a vertical boiler. He was there below me, and, upon my word, to look at him was as edifying as seeing a dog in a parody of breeches and a feather hat, walking on his hind legs.

In addition, not everyone is as generous in bestowing credit to Conrad for raising consciousness on these issues. Notably, Chinua Achebe, author of Things Fall Apart , wrote an angry and controversial essay criticising Heart of Darkness , chiefly for its assumption of ‘civilisation’, as defined by the West with Africa and Africans outside of it, and the omission of any African voice speaking to the issues raised in the novel.

While I won’t be defending Conrad on these charges, I do want to say a couple of things that add to the complexity of how to read and interpret Heart of Darkness . The first is that Heart of Darkness is based heavily on Conrad’s own experiences in the Congo. Like Marlow, Conrad was also hired to captain a steamboat whose previous captain had been killed by natives. This edition of Heart of Darkness includes excerpts from Conrad’s Congo Diary . It shows that in Heart of Darkness the line between fact and fiction, between reportage and storytelling is blurred. While we consider the issue of how much the novel speaks out against racism and exploitation and whether it is able to completely escape racism itself, we should also ask to what extent it provides an accurate window into a time, a place and a people and to both the racism and abhorrence of it in that context.

Which leads to the second thing I wanted to say. Fiction has the power to transport the reader and allow them to vicariously experience and empathise with the lives of others. When fiction was written or set in the past it allows the reader to time-travel as well. It is not the characters and the author who travel to our time for us to judge them by our standards, as satisfying as some might find that. Rather it is the reader who is transported to their time to glimpse what that life was like. Understandably, some might not find it a pleasant experience in some cases. Some might also object to any suggestion that we should feel grateful for how far things have come, given how much is left to do and the fate of those born to soon, which is fine. But there is still much to learn from the past. At least, if we don’t wish to feel grateful, we should also avoid its mirror; complacency.

Heart of Darkness is often cited as an early example of the modernist style that would become prevalent in the coming decades. That is clear to see in parts two and three of the novella. While the novel had a beautiful beginning and an engrossing hook of mystery it soon becomes difficult. As Marlow edges closer to the edges of the map, his storytelling begins slipping into stream-of-consciousness, becomes disjointed, unstructured, dreamlike. I admittedly had difficulty following what was really going on and how to interpret it.

In the end, I can’t say I greatly enjoyed Heart of Darkness , but maybe my expectations were too high. Maybe I was expected Apocalypse Now in book form! It is interesting how this novella, largely ignored when it was first published, and even its author considered it to be a minor work, came to be seen as highly influential and a standard text for high-school and university students. Perhaps its effort to speak to racism and colonial exploitation made it more relevant as time went on, both for what it achieved in that regard and for where it failed. Perhaps its modernist technique lends it enough ambiguity to make interpretation futile and subjective, vulnerable to endless analysis and reinterpretation, leaving the reader to see what they expect to see in it. Or perhaps that same technique makes it an important study as an antecedent for those who came in its wake – James Joyce, Virginia Woolf, William Faulkner among them.

Share this:

One comment.

Agree with you about the effectiveness of that opening – it always strikes me that it resembles an impressionist painting of the scene

Leave a comment Cancel reply

This site uses Akismet to reduce spam. Learn how your comment data is processed .

- Already have a WordPress.com account? Log in now.

- Subscribe Subscribed

- Copy shortlink

- Report this content

- View post in Reader

- Manage subscriptions

- Collapse this bar

"Heart of Darkness" Review

Delcommune, Alexandre/Wikimedia Commons/Public Domain

- Authors & Texts

- Top Picks Lists

- Study Guides

- Best Sellers

- Plays & Drama

- Shakespeare

- Short Stories

- Children's Books

Written by Joseph Conrad on the eve of the century that would see the end of the empire that it so significantly critiques, Heart of Darkness is both an adventure story set at the center of a continent represented through breathtaking poetry , as well as a study of the inevitable corruption that comes from the exercise of tyrannical power.

A seaman sat upon a tugboat moored in the river Thames narrates the main section of the story. This man, named Marlow, tells his fellow passengers that he spent a good deal of time in Africa. In one instance, he was called upon to pilot a trip down the river Congo in search of an ivory agent, who was sent as part of the British colonial interest in an unnamed African country. This man, named Kurtz, disappeared without a trace—inspiring worry that he'd gone "native," been kidnapped, absconded with the company's money, or been killed by the insular tribes in the middle of the jungle. As Marlow and his crewmates move closer to the place Kurtz was last seen, he starts to understand the attraction of the jungle. Away from civilization, the feelings of danger and possibility start to become attractive to him because of their incredible power. When they arrive at the inner station, they find that Kurtz has become a king, almost a God to the tribesmen and women who he has bent to his will. He has also taken a wife, despite the fact he has a European fiance at home. Marlow also finds Kurtz ill. Although Kurtz doesn't wish it, Marlow takes him aboard the boat. Kurtz does not survive the journey back, and Marlow must return home to break the news to Kurtz's fiance. In the cold light of the modern world, he is unable to tell the truth and, instead, lies about the way Kurtz lived in the heart of the jungle and the way he died.

The Dark in Heart of Darkness

Many commentators have seen Conrad's representation of the "dark" continent and its people as very much a part of a racist tradition that has existed in Western literature for centuries. Most notably, Chinua Achebe accused Conrad of racism because of his refusal to see the Black man as an individual in his own right, and because of his use of Africa as a setting—representative of darkness and evil. Although it is true that evil—and the corrupting power of evil—is Conrad's subject, Africa is not merely representative of that theme. Contrasted with the "dark" continent of Africa is the "light" of the sepulchered cities of the West, a juxtaposition that does not necessarily suggest that Africa is bad or that the supposedly civilized West is good. The darkness at the heart of the civilized White man (particularly the civilized Kurtz who entered the jungle as an emissary of pity and science of process and who becomes a tyrant) is contrasted and compared with the so-called barbarism of the continent. The process of civilization is where the true darkness lies.

Central to the story is the character of Kurtz, even though he is only introduced late in the story, and dies before he offers much insight into his existence or what he has become. Marlow's relationship with Kurtz and what he represents to Marlow is really at the crux of the novel. The book seems to suggest that we are not able to understand the darkness that has affected Kurtz's soul—certainly not without understanding what he has been through in the jungle. Taking Marlow's point of view, we glimpse from the outside what has changed Kurtz so irrevocably from the European man of sophistication to something far more frightening. As if to demonstrate this, Conrad lets us view Kurtz on his deathbed. In the final moments of his life, Kurtz is in a fever. Even so, he seems to see something that we cannot. Staring at himself he can only mutter, "The horror! The horror!"

Oh, the Style

As well as being an extraordinary story, Heart of Darkness contains some of the most fantastic use of language in English literature. Conrad had a strange history: he was born in Poland, traveled though France, became a seaman when he was 16, and spent a good deal of time in South America. These influences lent his style a wonderfully authentic colloquialism. But, in Heart of Darkness , we also see a style that is remarkably poetic for a prose work . More than a novel, the work is like an extended symbolic poem, affecting the reader with the breadths of its ideas as well as the beauty of its words.

- Quotes From 'Heart of Darkness' by Joseph Conrad

- Why Was Africa Called the Dark Continent?

- Biography of Joseph Conrad, Author of Heart of Darkness

- 'Tarzan of the Apes,' An Adventure Novel With a Complicated Legacy

- "The Jungle Book" Quotes

- "The Black Cat" Study Guide

- Five Common Stereotypes About Africa

- 'Death of a Salesman' Themes and Symbols

- Biography of Chinua Achebe, Author of "Things Fall Apart"

- Gothic Literature

- Atlantis as It Was Told in Plato's Socratic Dialogues

- Edgar Allan Poe's Detailed Philosophy of Death

- Biography of Edgar Rice Burroughs, American Writer, Creator of Tarzan

- 'Lord of the Flies' Themes, Symbols, and Literary Devices

- 'Lord of the Flies' Overview

- Arthurian Romance

Heart of Darkness: Analysis and Themes

By Dr Oliver Tearle (Loughborough University)

First published in 1899, Heart of Darkness – which formed the basis of the 1979 Vietnam war film Apocalypse Now – is one of the first recognisably modernist works of literature in English fiction. Its author was the Polish-born Joseph Conrad, and English wasn’t his first language (or even, for that matter, his second).

As well as being a landmark work of modernism, Conrad’s novella also explores the subject of imperialism, and Conrad’s treatment of this subject has been met with both criticism and praise.

In this post, we’ll offer an analysis of Heart of Darkness in relation to these two key ideas: modernism and imperialism.

The Problem of Storytelling

In a letter of 5 August 1897 to his friend Cunninghame Graham, Joseph Conrad wrote: ‘One writes only half the book – the other half is with the reader.’

In other words, a book should leave the reader with room to manoeuvre: it should be, to borrow Hilary Mantel’s phrase, a book of questions rather than a book of answers. The reader makes up the meaning of the book as much as the writer. This is a key feature of modernist fiction, which is often impressionistic : giving us glimpses and hints but refusing to spell everything out to the reader.

With this in mind, it’s worth considering the moments when Marlow stops and interrupts the tried and tested literary framework of the novella. One of the questions which it’s very easy to trick people out with is the question, ‘Who is the narrator of Heart of Darkness?’ ‘Why, Marlow, of course!’

Except the narrator is not Marlow – not the main narrator, anyway. Marlow doesn’t address us , the reader; he addresses his friends on the boat, the Nellie , and then there is an unnamed narrator, one of the other people on the boat listening to Marlow, and it’s this unnamed individual who addresses us in his role as the conventional narrator.

And Marlow, who tells the story to the real narrator and his companions, cannot just sit and tell it. He has to check with his audience that they are ‘getting it’; and they’re not getting it, at least not fully. They’re having to work hard to ‘see’ what he’s recounting to them. That is, there’s a constant anxiety on Marlow’s part as to whether his audience – his ‘readers’, as it were – are understanding the story he’s telling them.

Marlow interrupts his narrative several times, at least once simply because he is despairing of the efficacy of his own storytelling technique. It’s the literary equivalent of ‘breaking the fourth wall’ – we may just about be beginning to imagine the scene in the heart of Africa when suddenly our imagination is jolted back to Marlow, sitting in a boat on the Thames.

We’re not invited to get too cosy with Marlow’s narrative, and not just because of the dark events he’s describing: the way he describes them is constantly making us question what we are being told:

Do you see the story? Do you see anything? It seems to me I am trying to tell you a dream—making a vain attempt, because no relation of a dream can convey the dream-sensation, that commingling of absurdity, surprise, and bewilderment in a tremor of struggling revolt, that notion of being captured by the incredible which is of the very essence of dreams …

Note the subtle play on the word ‘relation’ here, where as well as meaning ‘the telling of a dream’ (relating a story to someone), it also glimmers with the other meaning of ‘relation’, i.e., one who is related to us, such as a brother or sister. It is as if fiction, stories, are the cousins of dreams, in that they’re both narratives that are at once both vividly and yet only dimly remembered. That is, you remember some aspects of dreams vividly, and others only hazily.

And ‘hazily’ is just the word. Note how the narrator describes Marlow’s way of telling a story, in a passage from Heart of Darkness that has become famous:

But Marlow was not typical (if his propensity to spin yarns be excepted), and to him the meaning of an episode was not inside like a kernel but outside, enveloping the tale which brought it out only as a glow brings out a haze, in the likeness of one of these misty halos that sometimes are made visible by the spectral illumination of moonshine.

This passage pinpoints what Conrad is doing with Heart of Darkness : using the framework or basic structure of many an imperial adventure story of the late nineteenth century ( Heart of Darkness was originally serialised in Blackwood’s Magazine , which was known for its gung-ho tales set in exotic parts of the world which were under European imperial rule), but undermining it by questioning the very basis on which such stories are founded.

Language, as the multilingual Conrad knew, is an imperfect and flawed tool for conveying our experiences.

Delayed Decoding

‘Delayed decoding’ is Ian Watt’s term for the moments in Conrad’s fiction where the narrator withholds information from us so that we have to work out what’s going on bit by bit, just as the narrator himself (and it is always a him self with Conrad) had to at the time. As Watt himself writes, delayed decoding serves ‘mainly to put the reader in the position of being an immediate witness of each step in the process’.

It’s as if you were there, and as confused and bewildered by it all as the narrator himself was. A good example is the moment when Marlow comes upon the abandoned hut in the jungle, and finds a strange book on the ground which contains notes pencilled in the margins which, he tells us, appear to be written in cipher, or code.

He – and we – later find out that it’s not written in code, but Russian. He makes us wait until the point in the narrative when he found out his mistake before he corrects it. This has two effects: it brings us closer to Marlow’s own experience (we learn things as we go along, just as he did at the time), but it also makes us work harder as readers, since we are encouraged to appraise carefully everything we are told. We can’t trust anything we read.

Much modernist fiction may be written in the past tense, as Heart of Darkness is, but a good deal of modernist fiction is narrated as though it were written in the present tense . That is, it wants to recreate the immediacy of the experience, the way it felt for the character/narrator as it happened .

It’s as if it doesn’t trust the overly neat brand of hindsight which is offered by the traditional Victorian novel written in the perfect (past) tense. Delayed decoding is one of the chief ways that Conrad goes about recreating the ‘presentness’ of Marlow’s experience, the sense of what it was like for him – surrounded by things he’s only half-figured out – as these things were happening to him.

The literary critic F. R. Leavis, who was otherwise a great admirer of Conrad, remarked that Conrad often seemed ‘intent on making a virtue out of not knowing what he means.’ Certainly Conrad seems to enjoy uncertainty, obscurity – darkness, if you will, like the Heart of Darkness .

In The English Novel: An Introduction , Terry Eagleton remarks that Conrad’s prose is both vivid or concrete and ambiguous or equivocal. It’s like describing mist in very precise terms, or depicting something as solid and tangible as a spear in terms which seem to make it melt into the air. This takes us back to Marlow’s own comparison between the story he is telling his companions and the experience of a dream.

Heart of Darkness and imperialism

Imperialism is an important theme of Heart of Darkness , but this, too, is treated in both vivid yet ambiguous or hazy terms. As Eagleton observes, the problems with Conrad’s treatment of imperialism are several: first, his depiction of African natives comes across as stereotyped and insufficient (a criticism that Chinua Achebe memorably made), but second, Conrad depicts the whole imperialist mission as irrational and borderline mad.

This overlooks the Enlightenment rationalism that underpinned the European imperial mission: colonialists used their belief in their ‘superior’ reason as an excuse for enslaving other peoples are taking their resources.

This belief may have been misguided and immoral, but it was hardly ‘irrational’: to depict it as such rather lets imperialists off the hook for their crimes, as if they were not in their right minds when they committed their atrocities or plundered other nations for their wealth.

However, when compared with other writers of his period, Conrad can be viewed as a more thoughtful writer on empire than many other late nineteenth-century authors. Consider Marlow’s account of the dying African natives:

They were not enemies, they were not criminals, they were nothing earthly now – nothing but black shadows of disease and starvation, lying confusedly in the greenish gloom. … Then, glancing down, I saw a face near my hand. The black bones reclined at full length with one shoulder against the tree, and slowly the eyelids rose and the sunken eyes looked up at me, enormous and vacant, a kind of blind, white flicker in the depths of the orbs, which died out slowly.

This passage continues:

He had tied a bit of white worsted round his neck – Why? Where did he get it? Was it a badge – an ornament – a charm – a propitiatory act? Was there any idea at all connected with it? It looked startling round his black neck, this bit of white thread from beyond the seas.

Marlow is ‘horror-struck’ by the sight of these starving people, although he does go on to describe them as ‘creatures’, which strikes a discordant note to our modern ears. But it’s clear that Marlow is appalled by the plight of the natives where many colonialists of the time would have simply stepped over the bodies as an inconvenience.

From this, Marlow turns to describing the next European he meets:

When near the buildings I met a white man, in such an unexpected elegance of get-up that in the first moment I took him for a sort of vision. I saw a high starched collar, white cuffs, a light alpaca jacket, snowy trousers, a clean necktie, and varnished boots. No hat. Hair parted, brushed, oiled, under a green-lined parasol held in a big white hand. He was amazing, and had a penholder behind his ear.

The contrast could not be clearer. The ‘greenish gloom’ in which the dying African youth fades away has become that thing of comfort: the European’s ‘green-lined parasol’. The ‘bit of white worsted’ tied around the African’s neck is replaced by the ‘clean necktie’ of the colonialist.

Of course, the novella’s ultimate depiction of the corruption at the heart of the imperial mission is Mr Kurtz himself, who has set himself up as a god among the African natives. An fundamentally, here we are presented with more questions than answers. Kurtz is driven mad by it all – there’s imperialism as an irrational undertaking again – but what is equally telling is Marlow’s decision to lie to Kurtz’s fiancée when he visits her at the end of Heart of Darkness .

Is it because, to borrow Kurtz’s final words, ‘the horror’ would be too great? Is it an act of sympathy or cowardice: is Marlow complicit in the horrors of imperialism in continuing to insulate those ‘back home’ from the atrocities which are carried out abroad so that, for instance, Kurtz’s fiancée can have that ‘grand piano’ (with its ivory keys, of course) standing in the corner of a room ‘like a sombre and polished sarcophagus’?

Discover more from Interesting Literature

Subscribe to get the latest posts to your email.

Type your email…

2 thoughts on “Heart of Darkness: Analysis and Themes”

Your analysis of Heart of Darkness was well written and held my interest throughout. Thank you!

A Conrad fan

It was perfectly possible to be both anti-imperialist and racist when Conrad wrote “Heart of Darkness”. “Race” was used in a much wider and vaguer sense than the word would be used now – where we would attribute something to “culture”, Conrad and his contemporaries attributed it to “race”. People spoke of the “races” of England. Josef Škvorecký examines the presence of the Russian Harlequin in Kurtz’s outpost in his novel “The Engineer of Human Souls” and in an essay “Why the Harlequin?” https://quod.lib.umich.edu/c/crossc/ANW0935.1984.001/269:21?rgn=author;view=image;q1=Skvorecky%2C+Josef

Comments are closed.

Subscribe now to keep reading and get access to the full archive.

Continue reading

Book Review: 'Heart Of Darkness'

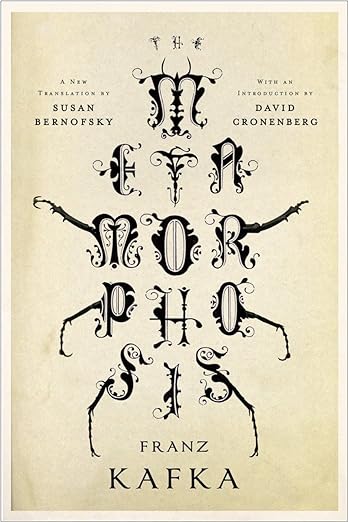

Still high on the list of the world’s 100 best novels, Joseph Conrad’s haunting “Heart of Darkness” continues to fascinate, mystify, and attract adaptors. Although Francis Ford Coppola’s 1979 award-winning film “Apocalypse Now,” starring Marlon Brando is, arguably, the most imaginative of the lot—moving Conrad’s brooding and inscrutable Congo tale to Vietnam—the 1902 novella inspired earlier films (Boris Karloff as the charismatic Kurtz in 1958, John Malkovich in 1993). “Heart of Darkness” has also been turned into radio dramas, theatre pieces, even an opera. But a graphic novel, a comic book?

Why not? as illustrator and cartoonist Peter Kuper might say. He had already taken on adaptations of Franz Kafka and Upton Sinclair, and, as he says in his introduction, which he calls “The Art of Darkness,” he read a lot about the book and showed his work to scholars. He even observes a three-part structure, following the first publication of the novella as a three-part magazine series in 1889. And he thought a lot about the controversy the book ignited in 1977, when the Nigerian novelist Chinua Achebe blasted “Heart of Darkness” as “bloody racist” and insisted it be removed from school curricula.

Those defending the book have argued that Achebe unfairly blamed Conrad for the racial Darwinism and European imperialism of the day. They also say Achebe overlooked the complex and nuanced stance of the narrator, Marlow. As he sits on board The Nellie in London, telling his shipmates about the time he went upriver to find the brilliant master ivory trader, Kurtz, then gravely ill, Marlow, drawn with sharp geometrical facial lines expressing disbelief or dismay is unambiguous about the cruelty and greed of the company he worked for, and sympathetic to the Africans—chained, diseased, dying, dead. In Kuper’s adaptation, they are seen close-up in grey ink-washed panels, terrified, peering out of the steamy dark jungle.

Kuper acknowledges “the confounding and repellent” aspects of Conrad’s book—the European sense of superiority, the stereotyped Congo primitives, but he also notes a resemblance to some attitudes today. In one contemporary nod he even has Marlow signing a non-disclosure agreement with the African Trading Company. Marlow tells his tale to his shipmates on board The Nellie, one of whom, in a sly move by Kuper, resembles Conrad. Kuper also keeps to Conrad’s framing device of narration within narration, Marlow being introduced by an unidentified first person point of view, who’s obviously interested in what Marlow has to say, while another seaman groans that they’re “fated” to hear once again about Marlow’s “inconclusive experiences.” Inconclusive? The “rapacious folly,” the “fascination of the abomination,” the depravity, “the horror, the horror” as Kurtz cries out at the end, stark white letters on black?

No, this is not Joseph Conrad’s “Heart of Darkness,” with its stunning imagery and rococo sentence rhythms, even though Kuper quotes liberally from the text. But it’s a prompt to read or reread Conrad. “ More than ever,” Kuper writes, “we need art that engages with the social discourse.” Kuper is clearly more illustrator here than cartoonist, especially in the opening and closing pages of his book where swashes of white and grey-flecked brush strokes on black snake into a river, with fangs.

Find anything you save across the site in your account

The Trouble with “Heart of Darkness”

By David Denby

“Who here comes from a savage race?” Professor James Shapiro shouted at his students.

“We all come from Africa,” said the one African-American in the class, whom I’ll call Henry, calmly referring to the supposition among most anthropologists that human life originated in sub-Saharan Africa. What Henry was saying was that there are no racial hierarchies among peoples—that we’re all “savages.”

Shapiro smiled. It was not, I thought, exactly the answer he had been looking for, but it was a good answer. Then he was off again. “Are you natural?” he roared at a girl sitting near his end of the seminar table. “What are the constraints for you? What are the rivets? Why are you here getting civilized, reading Lit Hum?”

It was the end of the academic year, and the mood had grown agitated, burdened, portentous. In short, we were reading Joseph Conrad, the final author in Columbia’s Literature Humanities (or Lit Hum) course, one of the two famous “great books” courses that have long been required of all Columbia College undergraduates. Both Lit Hum and the other course, Contemporary Civilization, are devoted to the much ridiculed “narrative” of Western culture, the list of classics, which, in the case of Lit Hum, begins with Homer and ends, chronologically speaking, with Virginia Woolf. I was spending the year reading the same books and sitting in on the Lit Hum classes, which were taught entirely in sections; there were no lectures. At the end of the year, the individual instructors were allotted a week for a free choice. Some teachers chose works by Dostoyevsky or Mann or Gide or Borges. Shapiro, a Shakespeare scholar from the Department of English and Comparative Literature (his book “Shakespeare and the Jews” will be published by Columbia University Press in January), chose Conrad.

The terms of Shapiro’s rhetorical questions—savagery, civilization, constraints, rivets—were drawn from Conrad’s great novella of colonial depredation, “Heart of Darkness,” and the students, almost all of them freshmen, were electrified. Almost a hundred years old, and familiar to generations of readers, Conrad’s little book has lost none of its power to amaze and appall: it remains, in many places, an essential starting point for discussions of modernism, imperialism, the hypocrisies and glories of the West, and the ambiguities of “civilization.” Critics by the dozen have subjected it to symbolic, mythological, and psychoanalytic interpretation; T. S. Eliot used a line from it as an epigraph for “The Hollow Men,” and Hemingway and Faulkner were much impressed by it, as were Orson Welles and Francis Ford Coppola, who employed it as the ground plan for his despairing epic of Americans in Vietnam, “Apocalypse Now.”

In recent years, however, Conrad—and particularly “Heart of Darkness”—has fallen under a cloud of suspicion in the academy. In the curious language of the tribe, the book has become “a site of contestation.” After all, Conrad offered a nineteenth-century European’s view of Africans as primitive. He attacked Belgian imperialism and in the same breath seemed to praise the British variety. In 1975, the distinguished Nigerian novelist and essayist Chinua Achebe assailed “Heart of Darkness” as racist and called for its elimination from the canon of Western classics. And recently Edward W. Said, one of the most famous critics and scholars at Columbia today, has been raising hostile and undermining questions about it. Certainly Said is no breaker of canons. But if Conrad were somehow discredited, one could hardly imagine a more successful challenge to what the academic left has repeatedly deplored as the “hegemonic discourse” of the classic Western texts. There is also the inescapable question of justice to Conrad himself.

Written in a little more than two months, the last of 1898 and the first of 1899, “Heart of Darkness” is both the story of a journey and a kind of morbid fairy tale. Marlow, Conrad’s narrator and familiar alter ego, a British merchant seaman of the eighteen-nineties, travels up the Congo in the service of a rapacious Belgian trading company, hoping to retrieve the company’s brilliant representative and ivory trader, Mr. Kurtz, who has mysteriously grown silent. The great Mr. Kurtz! In Africa, everyone gossips about him, envies him, and, with rare exception, loathes him. The flower of European civilization (“all Europe contributed to the making of Kurtz”), exemplar of light and compassion, journalist, artist, humanist, Kurtz has gone way upriver and at times well into the jungle, abandoning himself to certain . . . practices. Rifle in hand, he has set himself up as god or devil in ascendancy over the Africans. Conrad is notoriously vague about what Kurtz actually does, but if you said “kills some people, has sex with others, steals all the ivory,” you would not, I believe, be far wrong. In Kurtz, the alleged benevolence of colonialism has flowered into criminality. Marlow’s voyage from Europe to Africa and then upriver to Kurtz’s Inner Station is a revelation of the squalors and disasters of the colonial “mission”; it is also, in Marlow’s mind, a journey back to the beginning of creation, when nature reigned exuberant and unrestrained, and a trip figuratively down as well, through the levels of the self to repressed and unlawful desires. At death’s door, Marlow and Kurtz find each other.

Rereading a work of literature is often a shock, an encounter with an earlier self that has been revised, and I found that I was initially discomforted, as I had not been in the past, by the famous manner—the magnificent, alarmed, and (there is no other word) throbbing excitement of Conrad’s laboriously mastered English. Conrad was born in czarist-occupied Poland; though he heard English spoken as a boy (and his father translated Shakespeare), it was his third language, and his prose, now and then, betrays the propensity for high intellectual melodrama and rhymed abstraction (“the fascination of the abomination”) characteristic of his second language, French. Oh, inexorable, unutterable, unspeakable! The great British critic F. R. Leavis, who loved Conrad, ridiculed such sentences as “It was the stillness of an implacable force brooding over an inscrutable intention.” The sound, Leavis thought, was an overwrought, thrilled embrace of strangeness. (In Max Beerbohm’s parody: “Silence, the silence murmurous and unquiet of a tropical night, brooded over the hut that, baked through by the sun, sweated a vapour beneath the cynical light of the stars. . . . Within the hut the form of the white man, corpulent and pale, was covered with a mosquito-net that was itself illusory like everything else, only more so.”)

Read in isolation, some of Conrad’s sentences are certainly a howl, but one reads them in isolation only in criticism like Leavis’s or Achebe’s. Reading the tale straight through, I lost my discomfort after twenty pages or so and fell hopelessly under Conrad’s spell; thereafter, even his most heavily freighted constructions dropped into place, summing up the many specific matters that had come before. Marlow speaks:

“Going up that river was like travelling back to the earliest beginnings of the world, when vegetation rioted on the earth and the big trees were kings. An empty stream, a great silence, an impenetrable forest. The air was warm, thick, heavy, sluggish. There was no joy in the brilliance of sunshine. The long stretches of the waterway ran on, deserted, into the gloom of overshadowed distances. On silvery sandbanks hippos and alligators sunned themselves side by side. The broadening waters flowed through a mob of wooded islands. You lost your way on that river as you would in a desert and butted all day long against shoals trying to find the challenge till you thought yourself bewitched and cut off for ever from everything you had known once—somewhere—far away—in another existence perhaps. There were moments when one’s past came back to one, as it will sometimes when you have not a moment to spare to yourself; but it came in the shape of an unrestful and noisy dream remembered with wonder amongst the overwhelming realities of this strange world of plants and water and silence. And this stillness of life did not in the least resemble a peace. It was the stillness of an implacable force brooding over an inscrutable intention.”

In one sense, the writing now seemed close to the movies: it revelled in sensation and atmosphere, in extreme acts and grotesque violence (however indirectly presented), in shivering enigmas and richly phrased premonitions and frights. In other ways, though, “Heart of Darkness” was modernism at its most intellectually bracing, with tonalities, entirely contemporary and distanced, that I had failed to notice when I was younger—immense pride and immense contempt; a mood of barely contained revolt; and sardonic humor that verged on malevolence:

“I don’t pretend to say that steamboat floated all the time. More than once she had to wade for a bit, with twenty cannibals splashing around and pushing. We had enlisted some of these crew. Fine fellows—cannibals—in their place. They were men one could work with, and I am grateful to them. And, after all, they did not eat each other before my face: they had brought along a provision of chaps on the way for a hippo-meat which went rotten and made the mystery of the wilderness stink in my nostrils. Phoo! I can sniff it now. I had the Manager on board and three or four pilgrims [white traders] with their staves—all complete. Sometimes we came upon a station close by the bank clinging to the skirts of the unknown, and the white men rushing out of a tumble-down hovel with great gestures of joy and surprise and welcome seemed very strange, had the appearance of being held there captive by a spell. The word ‘ivory’ would ring in the air for a while—and on we went again into the silence, along empty reaches, round the still bends, between the high walls of our winding way, reverberating in hollow claps the ponderous beat of the stern-wheel.”

Out of sight of their countrymen back home, who continue to cloak the colonial mission in the language of Christian charity and improvement, the “pilgrims” have become rapacious and cruel. The cannibals eating hippo meat practice restraint; the Europeans do not. That was the point of Shapiro’s taunting initial sally: “savagery” is inherent in all of us, including the most “civilized,” for we live, according to Conrad, in a brief interlude between innumerable centuries of darkness and the darkness yet to come. Only the rivets, desperately needed to repair Marlow’s pathetic steamboat, offer stability—the rivets and the ship itself and the codes of seamanship and duty are all that hold life together in a time of moral anarchy. Marlow, meeting Kurtz at last, despises him for letting go—and at the same time, with breathtaking ambivalence, admires him for going all the way to the bottom of his soul and discovering there, at the point of death, a judgment of his own life. It is perhaps the most famous death scene written since Shakespeare:

“Anything approaching the change that came over his features I have never seen before and hope never to see again. Oh, I wasn’t touched. I was fascinated. It was as though a veil had been rent. I saw on that ivory face the expression of sombre pride, of ruthless power, of craven terror—of an intense and hopeless despair. Did he live his life again in every detail of desire, temptation, and surrender during that supreme moment of complete knowledge? He cried in a whisper at some image, at some vision—he cried out twice, a cry that was no more than a breath:

“ ‘The horror! The horror!’ ”

Much dispute and occasional merriment have long attended the question of what, exactly, Kurtz means by the melodramatic exclamation “The horror!” But surely one of the things he means is his long revelling in “abominations”—is own internal collapse. Shapiro’s opening questions set up a reading of the novella that interrogated the Western civilization of which Kurtz is the supreme representative and of which the students, in their youthful way, were representatives as well.

When Shapiro asked the class why they thought he had chosen “Heart of Darkness,” hands were going up before he had finished his question.

“You chose it because the whole core curriculum is embodied in Kurtz,” said Henry, who had answered Shapiro’s earlier question. “We embody this knowledge, and the book asks, Do we fall into the void—do we drown or come out with a stronger sense of self?”

Henry had turned the book into a test of the course and of himself. Conrad had great personal significance for him, which didn’t surprise me. An African-American from Baltimore, Henry, in his sophomore year at Columbia, had evolved into a fervent Nietzschean, and, though Conrad claimed to dislike Nietzsche, this was a Nietzschean text. The meaning of Henry’s life—his personal myth—required (he had said it in class many times) challenge, struggle, and self-transcendence. He was tall and strong, with a flattop “wedge” haircut and a loud, excited voice. Some months after this class, he got himself not tattooed but branded with the insignia of his black Columbia fraternity—an act of excruciating irony unavailable to members of the master race. Kurtz, however horrifying, was an exemplar for him as for Conrad’s hero, Marlow.

A freshman of Chinese descent from Singapore, who was largely reared on British and Continental literature, also saw the book as a test for Western civilization. But, unlike Henry, she hated the abyss. Kurtz was a seduced man, a portent of disintegration. “Can we deal with the knowledge we are seeking?” she asked. “Or will we say, with Kurtz, ‘The horror’?” For her, Kurtz’s outburst was an admission of the failure of knowledge.

And many others made similar remarks, All of a sudden, at the end of the course, the students were quite willing to see their year of education in Western classics as problematic. Their reading of “the great books” could be affirmed only if it was simultaneously questioned. No doubt Shapiro’s rhetorical questions had shaped their responses, but still their intensity surprised me.

“The book is a kind of test,” said a student from the Washington, D.C., area, who was normally a polite, bland schoolboy type. “Does its existence redeem the male hegemonic line of culture? Does it redeem education in this tradition?” By which I believe that he also meant to ask, “Could the existence of such a book redeem the crimes of imperialism?” That, at any rate, was my question.

The students were in good form, bold and free, and as the class went on they expounded certain points in the text, some of them holding the little paperback in their hands like preachers before the faithful. All year long, Shapiro had struggled to get them to read aloud, and with some emotional commitment to the words. And all too often they had droned, as if they were reading from a computer manual. But now they read aloud spontaneously, and their voices were alive, even ringing.

“For this course, it’s a kind of summing up, isn’t it?” Shapiro said. “We began with the journey to Troy.”

“It has a resemblance to all the journeys through Hell we’ve read,” said a student I will call Alex, a thin, ascetic-looking boy, the son of a professor. He cited the voyages to the underworld in the Odyssey and the Aeneid, and he cited Dante, whom Conrad, in one of his greatest moments, obviously had in mind. Marlow arrives at one of the trading company’s stations, a disastrous ramshackle settlement of wrecked machinery and rusting rails, and there encounters, under the trees, dozens of exhausted African workers who have been left to die. “It seemed to me I had stepped into the gloomy circle of some Inferno,” he says.

“They were dying slowly—it was very clear. They were not enemies, they were not criminals, they were nothing earthly now, nothing but black shadows of disease and starvation lying confusedly in the greenish gloom. Brought from all the recesses of the coast in the legality of time contracts, lost in uncongenial surroundings, fed on unfamiliar food, they sickened, became inefficient, and were then allowed to crawl away and rest. These moribund shapes were free as air—and nearly as thin. I began to distinguish the gleam of the eyes under the trees. Then glancing down I saw a face near my hand. The black bones reclined at full length with one shoulder against the tree, and slowly the eyelids rose and the sunken eyes looked up at me, enormous and vacant, a kind of blind, white flicker in the depths of the orbs which died out slowly. The man seemed young—almost a boy—but you know with them it’s hard to tell. I found nothing else to do but to offer him one of my good Swede’s ship’s biscuits I had in my pocket. The fingers closed slowly on it and held—there was no other movement and no other glance. He had tied a bit of white worsted round his neck—Why? Where did he get it. Was it a badge—an ornament—a charm—a propitiatory act? Was there any idea at all connected with it? It looked startling round his black neck this bit of white thread from beyond the seas.

“Near the same tree two more bundles of acute angles sat with their legs drawn up. One, with his chin propped on his knees, stared at nothing in an intolerable and appalling manner. His brother phantom rested its forehead as if overcome with a great weariness; and all about others were scattered in every pose of contorted collapse, as in some picture of a massacre or a pestilence.”

Despite the last sentence, which links the grove of death to ancient and medieval catastrophes, there is a sense here, as many readers have said, of something unprecedented in horror, something new on earth—what later became known as genocide. It is one of Conrad’s bitter ironies that at least some of the Europeans forcing the Congolese into labor are “liberals” devoted to the “suppression of savage customs.” What they had perpetrated in the Congo was not, perhaps, planned slaughter, but it was a slaughter nonetheless, and some of the students, pointing to the passage, were abashed. Western man had done this. We had created an Inferno on earth. “Heart of Darkness,” written at the end of the nineteenth century, resonates unhappily throughout the twentieth. Marlow’s shock, his amazement before the sheer strangeness of the ravaged human forms, anticipates what the Allied liberators of the concentration camps felt in 1945. The answer to the question “Does the book redeem the West?” was clear enough: No book can provide expiation for any culture. But if some crimes are irredeemable, a frank acknowledgment of the crime might lead to a partial remission of sin. Conrad had written such an acknowledgment.

That was the heart of the liberal reading, and Shapiro’s students rose to it willingly, gravely, ardently—and then, all of a sudden, the class fell into an acrimonious dispute. Alex was not happy with the way Shapiro and the other students were talking about Kurtz and the moral self-judgment of the West. He thought it was glib. He couldn’t see the book in apocalyptic terms. Kurtz was a criminal, an isolated figure. He was not representative of the West or of anything else. “Why is this a critique of the West?” he demanded. “No culture celebrates men like Kurtz. No culture condones what he did.” There was general protest, even a few laughs. “O.K.,” he said, yielding a bit. “It can be read as a critique of the West, but not only of the West.”

From my corner of the room, I took a hard look at him. He was as tight as a drum, dry, a little supercilious. Kurtz had nothing to do with him —that was his unmistakable attitude. He denied the connection that the other students acknowledged. He was cut off in some way, withholding himself. Yet I knew this student. I had seen him only in class, but there was something familiar in him that irked me, though exactly what it was I couldn’t say. Why was he so dense? The other students were not claiming personal responsibility for imperialism or luxuriating in guilt. They were merely admitting participation in an “advanced” civilization that could lose its moral bearings.

Henry, leaning back in his chair—against the wall, behind Alex, who sat at the table—insisted on an existential reading. “Kurtz is an Everyman figure,” he said. “He gets down to the soul, below the layers of parents, religion, society.”

Alex hotly disagreed. They were talking past each other, offering different angles of approach, but there was an edge to their voices which suggested an animus that went beyond mere disagreement. There was an awkward pause, and some of the students stirred uneasily. I had never seen these two quarrel in the past, and what they said presented no grounds for anger, but when each repeated his position, anger filled the room. Shapiro tried to calm things down, and the other students looked at one another in wonder and alarm. The argument between Alex and Henry wasn’t about race, yet race unmistakably hovered over it. In a tangent, Henry brought up the way Conrad, reflecting European assumptions of his time, portrayed the Africans as wild and primitive. He started to make a case similar to Achebe’s (whose hostile essay is included in the current Norton Critical Edition of the text), then stopped in midsentence, abruptly abandoning his position. In our class on “King Lear” and at other times over the past several months, he had argued explicitly as a black man. But at that moment he wasn’t interested. A greater urgency overcame him—not the racial but the existential issue, his own pressing need for identification not just as an African-American but as an embattled man. “Good and evil are conventions,” he said. “They collapse under stress.” And this, he insisted, was true for everyone.

“The book is also about the difference between good and evil,” Alex retorted. “Everyone judges Kurtz.” But this is not correct. Marlow judges Kurtz; Conrad judges Kurtz. But back in Brussels he is mourned as an apostle of enlightenment.

I looked a little closer. Alex was like the fabled “wicked son” in the Passover celebration, the one who says to the others “Why is this important to you ?”—denying a personal connection with an event of mesmerizing significance. I knew him, all right. A pale, narrow face, a bony nose surmounted by glasses, a paucity of flesh, a general air of asexual arrogance. He was very bright and very young. Of all the students in Shapiro’s class, he was—I saw it now—the closest to what I had been at eighteen or nineteen. He was incomparably more self-assured and articulate, but I recognized him all too well. And I was startled. The middle-aged reader, uneasy with earlier versions of himself, little expects his simulacrum to rise up as a walking ghost.

Henry sat sheathed in a green turtleneck sweater, dark glasses, and a baseball cap; I couldn’t see his expression. But Shapiro’s was clear: he was not happy. He had perhaps gone a little too far with his rhetorical questions, striking sparks that threatened to turn into a conflagration, and he quickly moved the conversation in a different direction, getting the students to explicate Conrad’s use of the word “darkness.” Conrad lets us know that even England—where Marlow sits, telling his story—used to be one of the dark places of the earth. For a while, teacher and students explicated the text in a neutral way. All year long, Shapiro had gone back and forth between analyzing the structure and language of the books and attacking the students’ complacencies with rhetorical questions. But sober analysis wasn’t what he wanted, not of this text, and he soon returned to the complicity of the West, and even the Western universities, in a policy that King Leopold II of the Belgians—the man responsible for some of the worst atrocities of colonial Africa—always referred to as noble and self-sacrificing.

“How else would you guys be civilized except for ‘the noble cause’?” Shapiro said. “You guys are all products of the noble cause. Columbia’s motto, translated from the Latin, is ‘In Thy light shall we see light.’ That’s the light that is supposed to penetrate the heart of darkness, isn’t it?”

“But enlightenment comes only by way of darkness,” said Henry, still at it, and Alex demurred angrily again—no darkness for him—and for a terrible moment I thought they were actually going to come to blows. The women in the class, who for the most part had been silent during these exchanges, were appalled and afterward muttered angrily, “It’s a boy thing, macho showing off. ‘Who’s the biggest intellectual?’ ” True, but maybe it was also a race thing. Though Shapiro restored order, something had broken, and the class, which had begun so well, with everyone joining in and expounding, had come unriveted.

Is “Heart of Darkness” a depraved book? The following is one of the passages Chinua Achebe deplores as racist:

“We were wanderers on a prehistoric earth, on an earth that wore the aspect of an unknown planet. We could have fancied ourselves the first of men taking possession of an accursed inheritance, to be subdued at the cost of profound anguish and of excessive toil. But suddenly as we struggled round a bend there would be a glimpse of rush walls, of peaked grass-roofs, a burst of yells, a whirl of black limbs, a mass of and clapping, of feet stamping, of bodies swaying, of eyes rolling under the droop of heavy and motionless foliage. The steamer toiled along slowly on the edge of a black and incomprehensible frenzy. The prehistoric man was cursing us, praying to us, welcoming us—who could tell? We were cut off from the comprehension of our surroundings; we glided past like phantoms, wondering and secretly appalled, as sane men would be before an enthusiastic outbreak in a madhouse. We could not understand because we were too far and could not remember because we were travelling in the night of first ages, of those ages that are gone, leaving hardly a sign—and no memories. “The earth seemed unearthly. We are accustomed to look upon the shackled form of a conquered monster, but there—there you could look at a thing monstrous and free. It was unearthly and the men were . . . No they were not inhuman. Well, you know that was the worst of it—this suspicion of their not being inhuman. It would come slowly to one. They howled and leaped and spun and made horrid faces, but what thrilled you was just the thought of their humanity—like yours—the thought of your remote kinship with this wild and passionate uproar. Ugly. Yes, it was ugly enough, but if you were man enough you would admit to yourself that there was in you just the faintest trace of a response to the terrible frankness of that noise, a dim suspicion of there being a meaning in it which you—you so remote from the night of first ages—could comprehend.”

Achebe believes that “Heart of Darkness” is an example of the Western habit of setting up Africa “as a foil to Europe, a place of negations . . . in comparison with which Europe’s own state of spiritual grace will be manifest.” Conrad, obsessed with the black skin of Africans, had as his real purpose the desire to comfort Europeans in their sense of superiority: “ ‘Heart of Darkness’ projects the image of Africa as ‘the other world,’ the antithesis of Europe and therefore of civilization, a place where man’s vaunted intelligence and refinement are finally mocked by triumphant bestiality.” Achebe dismisses the grove-of-death passage and others like it as “bleeding-heart sentiments,” mere decoration in a book that “parades in the most vulgar fashion prejudices and insults from which a section of mankind has suffered untold agonies and atrocities in the past and continues to do so in many ways and many places today,” and he adds, “I am talking about a story in which the very humanity of black people is called in question.”

Chinua Achebe has written at least one great novel, “Things Fall Apart” (1958), a book I love and from which I have learned a great deal. Yet this article on Conrad (originally a speech delivered at the University of Massachusetts, Amherst, in 1975, and revised for the third Norton edition of the novel in 1987 and reprinted as well in Achebe’s 1988 collection of essays, “Hopes and Impediments”) is an act of rhetorical violence, and I recoiled from it. Achebe regards the book not as an expression of its time or as the elaboration of a fictional situation, in which a white man’s fears of the unknown are accurately represented, but as a general slander against Africans, a simple racial attack. As far as Achebe is concerned, Africans have struggled to free themselves from the prison of colonial discourse, and for him reading Conrad meant reëntering the prison: “Heart of Darkness” is a book in which Europeans consistently have the upper hand.

Reading Achebe, I wanted to argue that most of the students in the Lit Hum class—not Europeans but an American élite—had seen “Heart of Darkness” as a representation of the West’s infamy, and hardly as an affirmation of its “spiritual grace.” I wanted to argue as well that everything in “Heart of Darkness”—not just the spectacular frights of the African jungle but everything, including the city of Brussels and Marlow’s perception of every white character—is rendered sardonically and nightmarishly as an experience of estrangement and displacement. Conrad certainly describes the Africans gesticulating on the riverbank as a violently incomprehensible “other.” But consider the fictional situation! Having arrived fresh from Europe, Marlow, surrounded by jungle, commands a small steamer travelling up the big river en route to an unknown destiny—death, perhaps. He is a character in an adventure story, baffled by strangeness. Achebe might well have preferred that Marlow engage the Africans in conversation or, at least, observe them closely and come to the realization that they, too, are a people, that they, too, are souls, have a destiny, spiritual struggles, triumphs and disasters of selfhood. But could African selfhood be described within this brief narrative, with its extraordinary physical and philosophical momentum, and within Conrad’s purpose of exposing the “pitiless folly” of the Europeans? Achebe wants another story, another hero, another consciousness. As it happens, Marlow, regarding the African tribesmen as savage and incomprehensible, nevertheless feels a kinship with them. He recognizes no moral difference between himself and them. It is the Europeans who have been demoralized.

But what’s the use? Though Achebe is a novelist, not a scholar, variants of his critique have appeared in many academic settings and in response to many classic works. Such publications as Lingua Franca are often filled with ads from university presses for books about literature and race, literature and gender, literature and empire. Whatever these scholars are doing in the classroom, they are seeking to make their reputations outside the classroom with politicized views of literature. F. R. Leavis’s criterion of greatness in literature—moral seriousness—has been replaced by the moral aggressiveness of the academic critic in nailing the author to whatever power formation existed around him. “Heart of Darkness” could indeed be read as racist by anyone sufficiently angry to ignore its fictional strategies, its palpable anguish, and the many differences between Conrad’s eighteen-nineties consciousness of race and our own. At the same time, parts of the academic left now consider the old way of reading fiction for pleasure, for enchantment—my falling hopelessly under Conrad’s spell—to be naïve, an unconscious submission to political values whose nature is disguised precisely by the pleasures of the narrative. In some quarters, pleasure in reading has itself become a political error, rather like sex in Orwell’s “1984.”

As much as Conrad himself, Edward W. Said is a self-created and ambiguous figure. A Palestinian Christian (from a Protestant family), he was brought up in Jerusalem and Cairo, but has built a formidable career in America, where he has assumed the position of the exiled literary man in extremis—an Arab critic of the West who lives and works in the West, a reader who is at home in Western literature but makes an active case for non-Western literature. Said loathes insularity and parochialism, and has disdained “flat-minded” approaches to reading. Over the years, he has gained many disciples and followers, some of whom he has recently chastised for carrying his moral and political critiques of Western literature to the point of caricature. Said has repeatedly discouraged any attempt to “level” the Western canon.

His most famous work is the remarkable “Orientalism” (1978), a charged analysis of the Western habit of constructing an “exotic” image of the Muslim East as an aid to controlling it. In 1993, Said published “Culture and Imperialism” as a sequel to that book, and part of his intention is to bring to account the great European nineteenth- and twentieth-century writers, examining and judging them as a way of combatting the notion—still alive today, Said says—that Europeans and Americans have the right to govern the inhabitants of the Third World.

Most imaginative writers of the nineteenth century, Said maintains, failed to connect their work, their own spiritual practice, to the squalid operations of colonialism. Such writers as Austen, Carlyle, Thackeray, Dickens, Tennyson, and Flaubert were heroes of culture who either harbored racist views of the subject people then dominated by the English and the French or merely acquiesced in the material advantages of empire. They took empire for granted as a space in which their characters might roam and prosper; they colluded in evil. Here and there, one could see in their work shameless traces of the subordinated world: a sugar plantation in Antigua whose earnings sustain in English luxury a landed family (the Bertrams) in Austen’s “Mansfield Park”; a central character in Dickens’s “Great Expectations” (the convict Magwitch) who enriches himself in the “white colony” of Australia and whose secret bequest turns Pip, the novel’s young hero, into a “London gentleman.” These novels, Said says, could not be fully understood unless their connections to the colonial assumptions and practices in the culture at large were analyzed. But how important, I wonder, is the source of the money to either of these novels? Austen mentions the Antigua plantation only a few times; exactly where the Bertrams’ money came from clearly did not interest her. And if Magwitch had made his pile not in Australia but in, say, Scotland, by illegally cornering the market in barley or mash, how great a difference would it have made to the structural, thematic, and metaphorical substance of “Great Expectations”? Magwitch would still be a disreputable convict whom Pip would have to reject as a scoundrel or accept as his true spiritual father. Were these novels, as literature, seriously affected by the alleged imperial nexus? Or is Said making lawyerlike points, not out of necessity but merely because they can be made? Indeed, one begins to suspect that a work like “Mansfield Park” is useful to Said precisely because it’s such an outlandish example. For if Jane Austen is heavily involved in the creation of imperialism, then every music-hall show, tearoom menu, and floral arrangement is also involved. The West’s cultural innocence must be brought to the bar of justice.

In the end, isn’t Said’s thesis a vast tautology, an assumption that imperialism did, indeed, receive the support of a structure that produced . . . imperialism? By Said’s measure, few writers would escape censure. Proust? Indifferent to French exploitation of North African native workers. (And where did the cork that lined the walls of his bedroom come from? Morocco? The very armature of Proust’s aesthetic contemplation partakes of imperial domination.) Henry James? Failed to inquire into the late-nineteenth-century industrial capitalism and overseas expansion that made possible the leisure, the civilized discourse, and the spiritual anguish of so many of his characters. James’s celebrated refinement was as much a product and an expression of American imperialism as Theodore Roosevelt’s pugnacious jingoism. And so on.

When Said arrives at “Heart of Darkness” (a book he loves), he asserts that Conrad, as much as Marlow and Kurtz, was enclosed within the mind-set of imperial domination and therefore could not imagine any possibilities outside it; that is, Conrad could imagine Africans only as ruled by Europeans. It’s perfectly true that “Heart of Darkness” contains a few widely spaced and ambiguous remarks that appear to praise the British variety of overseas domination. But how much do such remarks matter against the overwhelming weight of all the rest—the awful sense of desolation produced by the physical chaos, the death and ravaging cruelty everywhere? What readers remember is the squalor of imperialism, and it’s surely misleading for Said to speak of “Heart of Darkness” as a work that was “an organic part of the ‘scramble for Africa,’ ” a work that has functioned ever since to reassure Westerners that they had the right to rule the Third World. If we are to discuss the question of the book’s historical effect, shouldn’t we ask, on the contrary, whether thousands of European and American readers may not have become nauseated by colonialism after reading “Heart of Darkness”? Said is so eager to find the hidden power in “Heart of Darkness” that he underestimates the power of what’s on the surface. Here is his summing up:

Kurtz and Marlow acknowledge the darkness, the former as he is dying, the latter as he reflects retrospectively on the meaning of Kurtz’s final words. They (and of course Conrad) are ahead of their time in understanding that what they call “the darkness” has an autonomy of its own, and can reinvade and reclaim what imperialism has taken for its own. But Marlow and Kurtz are also creatures of their time and cannot take the next step, which would be to recognize that what they saw, disablingly and disparagingly, as a non-European “darkness” was in fact a non-European world resisting imperialism so as one day to regain sovereignty and independence, and not, as Conrad reductively says, to reestablish the darkness. Conrad’s tragic limitation is that even though he could see clearly that on one level imperialism was essentially pure dominance and land-grabbing, he could not then conclude that imperialism had to end so that “natives” could lead lives free from European domination. As a creature of his time, Conrad could not grant the natives their freedom, despite his severe critique of the imperialism that enslaved them.

I have read this passage over and over, each time with increasing disbelief. It’s not enough that Conrad captured the soul of imperialism, the genocidal elimination of a people forced into labor: no, his “tragic limitation” was his failure to “grant the natives their freedom.” Perhaps Said means something fragmentary—a tiny gesture, an implication, a few words that would suggest the liberated future. But I still find the idea bizarre as a suggested improvement of “Heart of Darkness,” and my mind is flooded with visions from terrible Hollywood movies. Mist slowly lifts from thick, dark jungle, revealing a rainbow in the distance; Kurtz, wearing an ivory necklace, gestures to the jungle as he speaks to a magnificent-looking African chief. “Someday your people will throw off the colonial oppressor. Someday your people will be free. ”

Dear God, a vision of freedom ? After the grove of death? Wouldn’t such a vision amount to the grossest sentimentality? Instead of doing what Said wants, Conrad says that England, too, has been one of the dark places of the earth. Throughout the book, he insists that the darkness is in all men. Conrad is as stern, unyielding, and pessimistic as Said is right-minded, positive, and banal.

Achebe indulges a similar sentimentality. Conrad, he says, was so obsessed with the savagery of the Africans that he somehow failed to notice that Africans just north of the Congo were creating great works of art—making the masks and other art works that only a few years later would astound such painters as Vlaminck, Derain, Picasso, and Matisse, thereby stimulating a new direction in European art. “The point of all this,” Achebe writes, “is to suggest that Conrad’s picture of the people of the Congo seems grossly inadequate.”

But Conrad certainly did not offer “Heart of Darkness” as “a picture of the peoples of the Congo,” any more than Achebe’s “Things Fall Apart,” set in a Nigerian village, purports to be a rounded picture of the British overlords. Conrad, as much as his master, Henry James, was devoted to a ruthless notion of form. Short as it is—only about thirty-five thousand words—“Heart of Darkness” is a mordantly ironic tale of rescue enfolding a philosophical meditation on the complicity between “civilization” and savagery. Conrad practices a narrow economy and omits a great deal. Economy is also a remarkable feature of the art of Chinua Achebe; and no more than Conrad should he be required to render a judgment for all time on every aspect of African civilization.

Achebe wants “Heart of Darkness” ejected from the canon. “The question is whether a novel which celebrates this dehumanization, which depersonalizes a portion of the human race, can be called a great work of art,” he writes. “My answer is: No, it cannot.” Said, to be sure, would never suggest dropping Conrad from the reading lists. Still, one has to wonder if blaming writers for what they fail to write about is not an extraordinarily wrongheaded way of reading them. Among the academic left, literature now inspires restless impatience. Literature excludes: it’s about one thing and not another, represents one point of view and not another, “empowers” one class or race but not another. Literature lacks the perfection of justice, in which all voices must be heard, weighed, balanced. European literature, in particular, is guilty of association with the “winners” of history. Jane Austen is culpable because she failed to dramatize the true nature of colonialism; Joseph Conrad is guilty because he did dramatize it. They are guilty by definition and by category.

In the end, Achebe’s and Said’s complaints come down to this: Joseph Conrad lacked the consciousness of race and imperial power which we have today. Poor, stupid Conrad! Trapped in his own time, he could do no more than write his books. A self-approving moral logic has become familiar on the academic left: So-and-so’s view of women, people of color, and the powerless lacks our amplitude, our humanity, our insistence on the inclusion in discourse of all people. One might think that elementary candor would require the academy to render gratitude to the older writers for yielding such easily detected follies.

Why am I so angry? A disagreeable essay or book does not spell the end of Western civilization, and liberal humanists, of all people, should be able—even required—to listen to points of view that are contrary to their own. But what Achebe and Said (and a fair number of other politicized critics) are offering is not simply a different interpretation of this or that work but something close to an attack on the moral legitimacy of literature.

“There is no way for me to understand your pain,” Henry said the next time the class met, speaking to everyone in general but perhaps to Alex in particular. “Nor is there any way for you to understand mine. The only common ground we have is that we can glimpse the horror.”

It was a portentous remark for so young a man, but he backed it up. Launching into a formal presentation of his ideas about “Heart of Darkness,” he rose from his seat behind Alex to speak. At one point, shouting with excitement, he brushed past him—“Watch out, Alex!” he warned—and threw some coins into the air, first catching them and then letting them drop to the table, where they landed with a clatter and rolled this way and that. Everyone jumped. “That’s what the wilderness does,” he said. “It disperses what we try to hold under control. Kurtz went in and saw that chaos.”

Henry had a talent for melodrama. “Chaos” was another Conradian notion, and I shuddered; our first class on Conrad had come close to breaking apart. Today, however, Shapiro had restored civility, beginning the class with a sombre speech. Hunching over the long table, his voice low, he said, “I had to feel a little despair the other day.” He warned the students against shouting past one another. He spoke very slowly of his own ambivalence in teaching a book that challenges the very nature of Western society. “It’s very hard when you teach a course like Lit Hum, which the outside world represents as the normative, or even conservative, view of social values—it’s very hard to find yourself. As you read Conrad, do you say, ‘Am I going to step away from this culture?’ Or do you say, ‘I’m going to interact with it in some way that recognizes the contradictions and lies that culture tells itself’?”

And Shapiro went on, slowly reëstablishing the frame of his class, situating the book in the year’s work and in the work of the élite university that sits on a hill above Harlem.

Looking back on our little Kulturkampf, I realize now that however much I disliked Achebe’s and Said’s approach, they helped me to understand what happened in the classroom. Just as Alex fought so angrily to keep Western civilization untouched by the stain of Kurtz’s crimes, I initially wanted “Heart of Darkness” to remain impervious to political criticism. In truth, I don’t think any political attack can seriously hurt Conrad’s novella. But to maintain that this book is not embedded in the world—to treat it innocently, as earlier critics did, as a garden of symbols, or as a quest for the Grail or the Father, or whatnot—is itself to diminish Conrad’s achievement. And to pretend that literature has no political component whatsoever is an equal folly.

However wrong or extreme in individual cases, the academic left has alerted readers to the possible hidden assumptions in language and point of view. Achebe and Said jarred me into seeing, for instance, that Shapiro’s way with “Heart of Darkness” was also highly political. I will quickly add that the great value of Shapiro’s “liberal” reading is that it did not depend on reductive control of the book’s meanings: when the class, provoked by Shapiro’s questions, broke down, it did not do so along the clichéd lines of whether Conrad was a racist, or an imperialist. On the contrary, an African-American student had read the book seeking not victimization through literature but self-realization through literature, and white and Asian students, with one exception, had tried in their different ways not to accuse the text but to interrogate themselves. Their responses participated in the liberal consensus of a great university, in which the act of self-criticism is one of the highest goals and a fulfillment of Western education itself. A benevolent politics, but politics nonetheless.

Reading Conrad again, one is struck by his extraordinary unease—and by what he made of it. In the end, his precarious situation both inside and outside imperialism should be seen not as a weakness but as a strength. Yes, Conrad the master seaman had done his time as a colonial employee, working for a Belgian company in 1890, making his own trip up the Congo. He had lived within the consciousness of colonial expansion. But if he had not, could he have written a book like “Heart of Darkness”? Could he have captured with such devastating force the peculiar, hollow triviality of the colonists’ ambitions, the self-seeking, the greed, the pettiness, the lies and evasions? Here was the last great Victorian, insisting on responsibility and order, and fighting, at the same time, an exhausting and often excruciating struggle against uncertainty and doubt of every kind, such that he cast every truth in his fictions as a mocking illusion and turned his morally didactic tale into an endlessly provocative and dismaying battle between stoical assumption of duty and perverse complicity in evil. Conrad’s sea-captain hero Marlow loathes the monstrous Kurtz, yet feels, after Kurtz’s death, an overpowering loyalty to the integrity of what Kurtz discovered in his furious descent into crime.