Find anything you save across the site in your account

Can We Have Prosperity Without Growth?

By John Cassidy

In 1930, the English economist John Maynard Keynes took a break from writing about the problems of the interwar economy and indulged in a bit of futurology. In an essay entitled “Economic Possibilities for Our Grandchildren,” he speculated that by the year 2030 capital investment and technological progress would have raised living standards as much as eightfold, creating a society so rich that people would work as little as fifteen hours a week, devoting the rest of their time to leisure and other “non-economic purposes.” As striving for greater affluence faded, he predicted, “the love of money as a possession . . . will be recognized for what it is, a somewhat disgusting morbidity.”

This transformation hasn’t taken place yet, and most economic policymakers remain committed to maximizing the rate of economic growth. But Keynes’s predictions weren’t entirely off base. After a century in which G.D.P. per person has gone up more than sixfold in the United States, a vigorous debate has arisen about the feasibility and wisdom of creating and consuming ever more stuff, year after year. On the left, increasing alarm about climate change and other environmental threats has given birth to the “degrowth” movement, which calls on advanced countries to embrace zero or even negative G.D.P. growth. “The faster we produce and consume goods, the more we damage the environment,” Giorgos Kallis, an ecological economist at the Autonomous University of Barcelona, writes in his manifesto, “ Degrowth .” “There is no way to both have your cake and eat it, here. If humanity is not to destroy the planet’s life support systems, the global economy should slow down.” In “ Growth: From Microorganisms to Megacities ,” Vaclav Smil, a Czech-Canadian environmental scientist, complains that economists haven’t grasped “the synergistic functioning of civilization and the biosphere,” yet they “maintain a monopoly on supplying their physically impossible narratives of continuing growth that guide decisions made by national governments and companies.”

Once confined to the margins, the ecological critique of economic growth has gained widespread attention. At a United Nations climate-change summit in September, the teen-age Swedish environmental activist Greta Thunberg declared, “We are in the beginning of a mass extinction, and all you can talk about is money and fairy tales of eternal economic growth. How dare you!” The degrowth movement has its own academic journals and conferences. Some of its adherents favor dismantling the entirety of global capitalism, not just the fossil-fuel industry. Others envisage “post-growth capitalism,” in which production for profit would continue, but the economy would be reorganized along very different lines. In the influential book “ Prosperity Without Growth: Foundations for the Economy of Tomorrow ,” Tim Jackson, a professor of sustainable development at the University of Surrey, in England, calls on Western countries to shift their economies from mass-market production to local services—such as nursing, teaching, and handicrafts—that could be less resource-intensive. Jackson doesn’t underestimate the scale of the changes, in social values as well as in production patterns, that such a transformation would entail, but he sounds an optimistic note: “People can flourish without endlessly accumulating more stuff. Another world is possible.”

Even within mainstream economics, the growth orthodoxy is being challenged, and not merely because of a heightened awareness of environmental perils. In “ Good Economics for Hard Times ,” two winners of the 2019 Nobel Prize in Economics, Abhijit Banerjee and Esther Duflo, point out that a larger G.D.P. doesn’t necessarily mean a rise in human well-being—especially if it isn’t distributed equitably—and the pursuit of it can sometimes be counterproductive. “Nothing in either our theory or the data proves the highest G.D.P. per capita is generally desirable,” Banerjee and Duflo, a husband-and-wife team who teach at M.I.T., write.

The two made their reputations by applying rigorous experimental methods to investigate what types of policy interventions work in poor communities; they conducted randomized controlled trials, in which one group of people was subjected to a given policy intervention—paying parents to keep their children in school, say—and a control group wasn’t. Drawing on their findings, Banerjee and Duflo argue that, rather than chase “the growth mirage,” governments should concentrate on specific measures with proven benefits, such as helping the poorest members of society get access to health care, education, and social advancement.

Banerjee and Duflo also maintain that in advanced countries like the United States the misguided pursuit of economic growth since the Reagan-Thatcher revolution has contributed to a rise in inequality, mortality rates, and political polarization. When the benefits of growth are mainly captured by an élite, they warn, social disaster can result.

That’s not to say that Banerjee and Duflo are opposed to economic growth. In a recent essay for Foreign Affairs , they noted that, since 1990, the number of people living on less than $1.90 a day—the World Bank’s definition of extreme poverty—fell from nearly two billion to around seven hundred million. “In addition to increasing people’s income, steadily expanding G.D.P.s have allowed governments (and others) to spend more on schools, hospitals, medicines, and income transfers to the poor,” they wrote. Yet for advanced countries, in particular, they think policies that slow G.D.P. growth may prove to be beneficial, especially if the result is that the fruits of growth are shared more widely. In this sense, Banerjee and Duflo might be termed “slowthers”—a label that certainly applies to Dietrich Vollrath, an economist at the University of Houston and the author of “ Fully Grown: Why a Stagnant Economy Is a Sign of Success .”

As his subtitle suggests, he thinks that slower rates of economic growth in advanced countries are nothing to worry about. Between 1950 and 2000, G.D.P. per person in the U.S. rose at an annual rate of more than three per cent. Since 2000, the growth rate has slowed to about two per cent. (Donald Trump has not, as he promised, boosted over-all G.D.P. growth to four or five per cent.) The phenomenon of slow growth is often bemoaned as “secular stagnation,” a term popularized by Lawrence Summers, the Harvard economist and former Treasury Secretary. Yet Vollrath argues that slower growth is appropriate for a society as rich and industrially developed as ours. Unlike other growth skeptics, he doesn’t base his case on environmental concerns or rising inequality or the shortcomings of G.D.P. as a measurement. Rather, he explains this phenomenon as the result of personal choices—the core of economic orthodoxy.

Vollrath offers a detailed decomposition of the sources of economic growth, which uses a mathematical technique that the eminent M.I.T. economist Robert Solow pioneered in the nineteen-fifties. The movement of women into the workplace provided a onetime boost to the labor supply; in its aftermath, other trends dragged down the growth curve. As countries like the United States have become richer and richer, Vollrath points out, their inhabitants have chosen to spend less time at work and to have smaller families—the result of higher wages and the advent of contraceptive pills. G.D.P. growth slows when the growth of the labor force declines. But this isn’t any sort of failure, in Vollrath’s view: it reflects “the advance of women’s rights and economic success.”

Vollrath estimates that about two-thirds of the recent slowdown in G.D.P. growth can be accounted for by the decline in the growth of labor inputs. He also cites a switch in spending patterns from tangible goods—such as clothes, cars, and furniture—to services, such as child care, health care, and spa treatments. In 1950, spending on services accounted for forty per cent of G.D.P.; today, the proportion is more than seventy per cent. And service industries, which tend to be labor-intensive, exhibit lower rates of productivity growth than goods-producing industries, which are often factory-based. (The person who cuts your hair isn’t getting more efficient; the plant that makes his or her scissors probably is.) Since rising productivity is a key component of G.D.P. growth, that growth will be further constrained by the expansion of the service sector. But, again, this isn’t necessarily a failure. “In the end, that reallocation of economic activity away from goods and into services comes down to our success,” Vollrath writes. “We’ve gotten so productive at making goods that this has freed up our money to spend on services.”

Taken together, slower growth in the labor force and the shift to services can explain almost all the recent slowdown, according to Vollrath. He’s unimpressed by many other explanations that have been offered, such as sluggish rates of capital investment, rising trade pressures, soaring inequality, shrinking technological possibilities, or an increase in monopoly power. In his account, it all flows from the choices we’ve made: “Slow growth, it turns out, is the optimal response to massive economic success.”

Vollrath’s analysis implies that all the major economies are likely to see slower growth rates as their populations age—a pattern first established in Japan during the nineteen-nineties. But two-per-cent growth isn’t negligible. If the U.S. economy continues to expand at this rate, it will have doubled in size by 2055, and a century from now it will be almost eight times its current size. If you think about growth-compounding in other rich countries, and developing economies growing at somewhat faster rates, you can readily summon up scenarios in which, by the end of the next century, global G.D.P. has risen fiftyfold, or even a hundredfold.

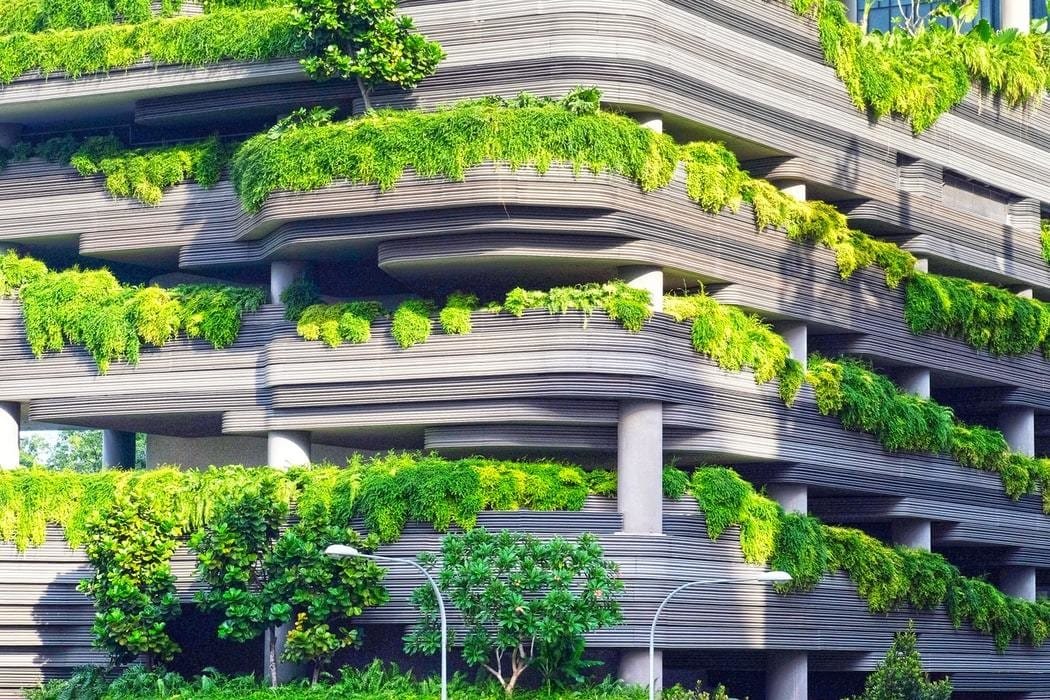

Is such a scenario environmentally sustainable? Proponents of “green growth,” who now include many European governments, the World Bank, the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development, and all the remaining U.S. Democratic Presidential candidates, insist that it is. They say that, given the right policy measures and continued technological progress, we can enjoy perpetual growth and prosperity while also reducing carbon emissions and our consumption of natural resources. A 2018 report by the Global Commission on the Economy and Climate, an international group of economists, government officials, and business leaders, declared, “We are on the cusp of a new economic era: one where growth is driven by the interaction between rapid technological innovation, sustainable infrastructure investment, and increased resource productivity. We can have growth that is strong, sustainable, balanced, and inclusive.”

This judgment reflected a belief in what’s sometimes termed “absolute decoupling”—a prospect in which G.D.P. can grow while carbon emissions decline. The environmental economists Alex Bowen and Cameron Hepburn have conjectured that, by 2050, absolute decoupling may appear “to have been a relatively easy challenge,” as renewables become significantly cheaper than fossil fuels. They endorse scientific research into green technology, and hefty taxes on fossil fuels, but oppose the idea of stopping economic growth. From an environmental perspective, they write, “it would be counterproductive; recessions have slowed and in some cases derailed efforts to adopt cleaner modes of production.”

For a time, official carbon-emissions figures seemed to support this argument. Between 2000 and 2013, Britain’s G.D.P. grew by twenty-seven per cent while emissions fell by nine per cent, Kate Raworth, an English economist and author, noted in her thought-provoking book, “ Doughnut Economics: Seven Ways to Think Like a 21st Century Economist ,” published in 2017. The pattern was similar in the United States: G.D.P. up, emissions down. Globally, carbon emissions were flat between 2014 and 2016, according to figures from the International Energy Agency. Unfortunately, this trend didn’t last. According to a recent report from the Global Carbon Project, carbon emissions worldwide have been edging up in each of the past three years.

The pause in the rise of emissions may well have been the temporary product of a depressed economy—the Great Recession and its aftermath—and the shift from coal to natural gas, which can’t be repeated. According to a recent report by the United Nations and a number of climate-research institutes, “Governments are planning to produce about 50% more fossil fuels by 2030 than would be consistent with a 2°C pathway and 120% more than would be consistent with a 1.5°C pathway.” (Those were the targets established in the 2016 Paris Agreement.) In a recent review of the literature about green growth, Giorgos Kallis and Jason Hickel, an anthropologist at Goldsmiths, University of London, concluded that “green growth is likely to be a misguided objective, and that policymakers need to look toward alternative strategies.”

Can such “alternative strategies” be implemented without huge ruptures? For decades, economists have cautioned that they can’t. “If growth were to be abandoned as an objective of policy, democracy too would have to be abandoned,” Wilfred Beckerman, an Oxford economist, wrote in “ In Defense of Economic Growth ,” which appeared in 1974. “The costs of deliberate non-growth, in terms of the political and social transformation that would be required in society, are astronomical.” Beckerman was responding to the publication of “The Limits to Growth,” a widely read report by an international team of environmental scientists and other experts who warned that unrestrained G.D.P. growth would lead to disaster, as natural resources such as fossil fuels and industrial metals ran out. Beckerman said that the authors of “The Limits to Growth” had greatly underestimated the capacity of technology and the market system to produce a cleaner and less resource-intensive type of economic growth—the same argument that proponents of green growth make today.

Whether or not you share this optimism about technology, it’s clear that any comprehensive degrowth strategy would have to deal with distributional conflicts in the developed world and poverty in the developing world. As long as G.D.P. is steadily rising, all groups in society can, in theory, see their living standards rise at the same time. Beckerman argued that this was the key to avoiding such conflict. But, if growth were abandoned, helping the worst off would pit winners against losers. The fact that, in many Western countries over the past couple of decades, slower growth has been accompanied by rising political polarization suggests that Beckerman may have been on to something.

Some degrowth proponents say that distributional conflicts could be resolved through work-sharing and income transfers. A decade ago, Peter A. Victor, an emeritus professor of environmental economics at York University, in Toronto, built a computer model, since updated, to see what would happen to the Canadian economy under various scenarios. In a degrowth scenario, G.D.P. per person was gradually reduced by roughly fifty per cent over thirty years, but offsetting policies—such as work-sharing, redistributive-income transfers, and adult-education programs—were also introduced. Reporting his results in a 2011 paper, Victor wrote, “There are very substantial reductions in unemployment, the human poverty index and the debt to GDP ratio. Greenhouse gas emissions are reduced by nearly 80%. This reduction results from the decline in GDP and a very substantial carbon tax.”

More recently, Kallis and other degrowthers have called for the introduction of a universal basic income, which would guarantee people some level of subsistence. Last year, when progressive Democrats unveiled their plan for a Green New Deal, aiming to create a zero-emission economy by 2050, it included a federal job guarantee; some backers also advocate a universal basic income. Yet Green New Deal proponents appear to be in favor of green growth rather than degrowth. Some sponsors of the plan have even argued that it would eventually pay for itself through economic growth.

There’s another challenge for growth skeptics: how would they reduce global poverty? China and India lifted millions out of extreme deprivation by integrating their countries into the global capitalist economy, supplying low-cost goods and services to more advanced countries. The process involved mass rural-to-urban migration, the proliferation of sweatshops, and environmental degradation. But the eventual result was higher incomes and, in some places, the emergence of a new middle class that is loath to give up its gains. If major industrialized economies were to cut back their consumption and reorganize along more communal lines, who would buy all the components and gadgets and clothes that developing countries like Bangladesh, Indonesia, and Vietnam produce? What would happen to the economies of African countries such as Ethiopia, Ghana, and Rwanda, which have seen rapid G.D.P. growth in recent years, as they, too, have started to join the world economy? Degrowthers have yet to provide a convincing answer to these questions.

Given the scale of the environmental threat and the need to lift up poor countries, some sort of green-growth policy would seem to be the only option, but it may involve emphasizing “green” over “growth.” Kate Raworth has proposed that we adopt environmentally sound policies even when we’re uncertain how they will affect the long-term rate of growth. There are plenty of such policies available. To begin with, all major countries could take more definitive steps to meet their Paris Agreement commitments by investing heavily in renewable sources of energy, shutting down any remaining coal-fired power plants, and introducing a carbon tax to discourage the use of fossil fuels. According to Ian Parry, an economist at the World Bank, a carbon tax of thirty-five dollars per ton, which would raise the price of gasoline by about ten per cent and the cost of electricity by roughly twenty-five per cent, would be sufficient for many countries, including China, India, and the United Kingdom, to meet their emissions pledges. A carbon tax of this kind would raise a lot of money, which could be used to finance green investments or reduce other taxes, or even be handed out to the public as a carbon dividend.

Taking energy efficiency seriously is also vital. In a 2018 piece for the New Left Review , Robert Pollin, an economist at the University of Massachusetts, Amherst, who has helped design Green New Deal plans for a number of states, listed several measures that can be taken, including insulating old buildings to reduce heat loss, requiring cars to be more fuel efficient, expanding public transportation, and reducing energy use in the industrial sector. “Expanding energy-efficiency investment,” he pointed out, “supports rising living standards because, by definition, it saves money for energy consumers.”

To ameliorate the effects of slower G.D.P. growth, policies such as work-sharing and universal basic income could also be considered—especially if the warnings about artificial intelligence eliminating huge numbers of jobs turn out to be true. In the United Kingdom, the New Economics Foundation has called for the standard workweek to be shortened from thirty-five to twenty-one hours, a proposal that harks back to Victor’s modelling and Keynes’s 1930 essay. Proposals like these would have to be financed by higher taxes, particularly on the wealthy, but that redistributive aspect is a feature, not a bug. In a low-growth world, it is essential to share what growth there is more equitably. Otherwise, as Beckerman argued many years ago, the consequences could be catastrophic.

Finally, rethinking economic growth may well require loosening the grip on modern life exercised by competitive consumption, which undergirds the incessant demand for expansion. Keynes, a Cambridge aesthete, believed that people whose basic economic needs had been satisfied would naturally gravitate to other, non-economic pursuits, perhaps embracing the arts and nature. A century of experience suggests that this was wishful thinking. As Raworth writes, “Reversing consumerism’s financial and cultural dominance in public and private life is set to be one of the twenty-first century’s most gripping psychological dramas.” ♦

News & Politics

By signing up, you agree to our User Agreement and Privacy Policy & Cookie Statement . This site is protected by reCAPTCHA and the Google Privacy Policy and Terms of Service apply.

By Caleb Crain

By Nathan Heller

By Benjamin Wallace-Wells

A recipe for a successful nation

Professor of Psychology and Business, University of Calgary

Disclosure statement

Piers Steel does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

University of Calgary provides funding as a founding partner of The Conversation CA.

University of Calgary provides funding as a member of The Conversation CA-FR.

View all partners

When you think of the ideal version of your nation, it likely reflects your own values. We vote in accordance with our values and live our own lives according to them as well.

Critical to the success of both people and their nations are the values they adopt. Personal values are central to where people end up in life. Values influence actions and these subsequent actions help determine life’s outcomes, both in terms of happiness and financial success.

Those who value friendship over work, for example, experience a different world than their more diligent counterparts. And as it is true for you, so is it true for your country.

At the national level, cultural values influence what institutions are formed and how they perform. It is difficult to maintain a democracy if the underlying values necessary to sustain it aren’t respected in the first place.

However, and here’s the twist, the values that shape personal success aren’t always the same as those that govern national success. Sometimes called “ the social dilemma ,” what is best associated with success for ourselves can be disastrous for the nation. So what is the value recipe for success?

We answered this question in our recent article “ The Happy Culture: A Theoretical, Meta-Analytic and Empirical Review of the Relationship Between Culture and Wealth and Subjective Well-Being .” Among one of the largest studies ever conducted, spanning over 40 years of data for both individuals and countries, we establish what values predict both a good life and a thriving nation.

The four core values

The values we studied were based on the work of the social psychologist, Geert Hofstede , who developed one of the oldest and most established cultural models. The terms used to describe these values were developed during the early 1970s and reflect the times:

Masculinity vs Femininity: Masculine values reflect a desire for achievement, ability to plan for the future but also conspicuous consumption or materialism, whereas feminine values are more socially oriented and altruistic.

Individualism vs Collectivism: Individualists essentially follow their own path, while collectivists let the needs or desires of the group determine their actions.

Low vs. High Power Distance: Power distance indicates the degree to which one accepts inequality, hierarchy or authoritarianism.

Low vs High Uncertainty Avoidance: High uncertainty avoidance reflects a desire for rules or consistency and a belief that the world is a dangerous place and what is new or unpredictable should be avoided.

Values for a successful life

So what values should you adopt? You probably want to know the ones that make you wealthy and happy. Focusing on wealth alone doesn’t cut it. Values turn out to be more important for predicting happiness than salary, with one sensible exception: Pay satisfaction.

For everything else, the values best associated with a happy and wealthy life were low individualism, low power distance — in other words, a lack of authoritarianism in your life — and low uncertainty avoidance.

Masculinity had a mixed effect. While the ability to plan for the future can be universally recommended, that “need for achievement” component comes at quite a cost. Those who score higher on masculinity make more money but also tend to be unhappier, despite the higher pay. By the way, this isn’t a new observation. Economist Adam Smith wrote about it more than 250 years ago.

We also looked at an element related to masculinity called gender inegalitarianism, which is typically studied in terms of how it adversely affects women — it’s similar to what we’re learning amid the ongoing Harvey Weinstein scandal . It is notable that chauvinism typically doesn’t benefit chauvinists themselves. It is among the best indicators of an unhappy life. Everyone would be better off with less of it.

Values for a successful nation

Moving on, we repeated our research strategy with 48 countries or regions, from Australia to Vietnam. Drawing on four decades of cultural indices as well as national well-being, corruption and GDP-per-capita data, we replicated some of our previous individual level relationships, but found them to be significantly stronger at the national level.

Repeatedly, values were key predictors of a successful nation but often in contradiction to popular or anecdotal advice. In stark contrast to the economic historian Niall Ferguson’s widely promoted killer cultural apps aimed at achieving prosperity, promoting the need for achievement as well as materialism , values associated with masculinity, is terrible for a nation, both in terms of happiness and wealth. Worse advice than Ferguson’s has rarely been given.

Hoping for a strong man? Expect the worst

A much better case can be made for promoting co-operation, trade and reciprocal altruism, all associated with more feminine cultures. High power distance and high uncertainty avoidance were excellent predictors of an incompetent or corrupt government that showed toxic trickle-down effects on the wealth and happiness of the population.

This constellation of values often manifests when people look for an authority or “strong man” to solve national problems, fear the outsider (especially immigrants) and have an over-reliance on prison and punishment as well as a willingness to trade liberty for security. A nation or two that is turning in this direction might pop into your mind right now. If so, expect even worse to come.

Individualism requires financial means

For the most part, the set of values that prove detrimental to individual success are the same for the nation, with one exception.

Individualism switches outcomes. While often negatively associated with a person’s individual well-being, nations that promote individual liberty and the freedom to follow one’s own path are indeed happiest, especially if these nations are wealthy.

Apparently, if emphasizing personal fulfilment, it is best to have the financial means to fulfil.

All of this can be considered a wake-up call.

Values play key role

Both economics and political science typically operate from the assumption that cultural values are irrelevant to the functioning of a nation.

With the steady rise of illiberal and dysfunctional democracies, we are learning that values do play a role, a lesson that increases in costs the slower we are to absorb it. In order to perform, our nation’s institutions need people with supporting underlying values that are considered important to the population.

Aside from regarding dangerously high levels of inequality as being desirable (high power distance, for example), fear is particularly poisonous to a nation (high uncertainty avoidance).

Unfortunately, fear is also particularly effective at maintaining a viewing audience, spurring all forms of media to emphasize, distort or even manufacture stories of threat. Disentangling the promotion of cultural toxins from the more beneficial roles of the Fourth Estate appears to be the challenge of our time .

- Masculinity

Research Fellow (Cultural Landscape Design)

Lecturer / Senior Lecturer - Marketing

Assistant Editor - 1 year cadetship

Executive Dean, Faculty of Health

Lecturer/Senior Lecturer, Earth System Science (School of Science)

- International edition

- Australia edition

- Europe edition

Dear America: writer, thinkers and activists on how to build a better country

We’ve asked a group of experts to share concrete ideas to address some of America’s deepest problems

- Guardian readers shared their own ideas for creating a better America. Read them here

America has some big problems that need fixing.

The last year laid bare hard truths: about existing inequalities made unbearably worse by the Covid-19 pandemic, about a democratic system dangerously vulnerable to its own institutional weaknesses, about the proliferating catastrophes heading our way if we don’t act with urgency to stop the climate crisis.

It’s our hope that the coming year will offer a fresh start. It’s certainly an opportunity for fresh ideas. We’ve asked nine experts to share one, concrete way to address some of America’s most intractable challenges. Their answers are below.

How to fix America’s misinformation crisis

Teach our children critical thinking By Rebecca Solnit

There is hardly a thing in the US that couldn’t benefit from change right now, but something I think about a lot is public education, from preschool to high school. If it were up to me, we’d throw out a lot of the existing curriculum and start over. The conspiracy theories and delusions across the political spectrum – from anti-vaxxers to QAnon devotees to climate deniers to Confederacy cosplayers – prove that we desperately need a citizenship equipped with critical thinking skills.

By this I mean the capacity to evaluate and factcheck information and sources, and to analyze them to decide what makes sense and who and what can be trusted. Over and over, I run into statements from people who don’t understand that the conclusion they’re brandishing can’t be reached from the data they’ve glommed on to or that their information is itself corrupt or simply wrong. I dream of a curriculum emphasizing research skills, analytical skills, practice in exercising judgment and using language with accuracy.

These things are vital for a functioning democracy and a society inoculated against conspiracy theories, hucksters and delusions. The current pandemic has shown us how dangerous is this capacity to believe things that don’t make sense, but are ideologically convenient, and Donald J Trump’s whole political career was about reaping the benefits of this incapacity.

Rebecca Solnit is a Guardian US columnist. She is also the author of Men Explain Things to Me and The Mother of All Questions. Her most recent book is Whose Story Is This? Old Conflicts, New Chapters

How to bridge the racial wealth gap

With reparations for slavery By Dedrick Asante-Muhammad

The United States – and its economy – is based on a white supremacist concentration of wealth and resources. To end this disparity, which rears its head in everything from the racial wealth divide to police brutality and mass incarceration, a massive redistribution of wealth and resources is required.

Today, African Americans collectively own just 4% of the nation’s total wealth. To own a share of wealth proportionate to their 13% of the population, African Americans would require another $10tn.

A long-term and consistent cash infusion will make a world of difference for wealth development, particularly for a community whose median household income is only $40,000. A 20-year injection of $20,000 annually to every African American who can identify an enslaved ancestor in the United States is the type of radical reform needed to build an American economy and society that gets us past the divisions and inequality of the past. Read more .

Dedrick Asante-Muhammad is the chief of race, wealth and community at the National Community Reinvestment Coalition and an associate fellow of the Institute for Policy Studies

How to fix inequality

Tax the wealth of the dead By Robert Reich

Already, 60% of America’s personal wealth is inherited. If present trends continue, it will be close to 80% in a few decades. So much for the myth of the “self-made man” or woman, and for America’s traditional disdain of aristocracy.

What to do? Joe Biden has rejected a tax on great wealth but he’s open to getting rid of the “stepped-up-basis on death” rule. This obscure tax provision allows heirs to avoid paying capital gains taxes on the increased value of assets accumulated during the life of the deceased.

Such untaxed gains account for more than half of the value of estates over $100m . If these capital gains were taxed at death, they would generate in excess of $400bn over the next decade .

It won’t solve economic inequality on its own, but it’s a good place to start.

Robert Reich, a former US secretary of labor, is professor of public policy at the University of California at Berkeley

How to fix America’s economy

Put workers at the center By Darren Walker

Time magazine just recognized frontline workers as 2020 “ Guardians of the Year ” – rightly so. For nine months, working people have toiled to keep us all afloat through unprecedented disaster.

And yet, even as they’re hailed as heroes, frontline workers have been treated as expendable. Already, America’s workers – especially Black and brown workers – have suffered extreme levels of infection, job loss and poverty.

If we want to honor these heroes, we can offer immediate relief by prioritizing them for vaccines and financial support. We can protect them and aid the recovery by adopting paid leave and sick days, ensuring personal protective equipment and enforcing and improving health and safety policies. And we must push for permanent reform – such as a comprehensive workers’ bill of rights – that addresses systemic inequalities and gives them access to well-paid employment, healthcare and affordable housing.

No one should be forced to choose between their lives and their livelihoods. We must reimagine our world with workers at the center.

Darren Walker is president of the Ford Foundation

How to tackle the climate emergency

For starters, cut the money pipeline By Bill McKibben

There’s no one way to fix climate change, of course – it’s the biggest problem humans have ever encountered. But convincing banks and asset managers to cut their ties with the fossil fuel industry would go a long way.

New York state recently decided to divest its $226bn pension fund from oil and gas – if Citibank and Barclays and Bank of America and BlackRock and the rest would follow suit, the crimp in the money pipeline that feeds the fires of global warming would make a huge difference.

JP Morgan Chase alone has poured a quarter-trillion dollars into fossil fuel since the Paris climate agreement – Donald Trump was not its only saboteur. It’s time for that kind of vandalism to end.

Bill McKibben is an author and Schumann distinguished scholar in environmental studies at Middlebury College, Vermont

How to create a more inclusive democracy

Build grassroots movements By Alejandra Gomez

In 2020, Lucha’s grassroots effort helped turn Arizona blue. Ours wasn’t just the largest progressive field campaign in Arizona – it was the only progressive field campaign in Arizona.

We started to organize ourselves in 2010 because we felt abandoned by the Democratic party, which did nothing to protect us from anti-immigrant policies threatening our communities.

We built a larger, diverse coalition that reflected the community. We created grassroots infrastructure and developed the leadership capacity of immigrant women in our communities. In 2016, alongside our coalition partners, we passed a higher minimum wage and defeated America’s toughest sheriff. We continued organizing our tías , abuelas y comadres across Arizona. By 2020, our coalition was able to energize a large coalition of Latinx, Black and Indigenous women and immigrant voters.

Arizona organizers showed what’s possible when you put resources into expanding the electorate and developing the next generation of leaders – mujeres , immigrants, and people of color. Now it’s up to the Democratic party to follow our lead if they truly want to win up and down the ballot. La Lucha sigue.

Alejandra Gomez, co-executive director of L ucha, has dedicated her life to a commitment to social, racial and economic justice by building power alongside community through grassroots organizing and mobilization

How to fix America’s water crisis

Start with rural America By Catherine Coleman Flowers

In the wealthiest country in the world, at least 2 million people lack access to basic water and sanitation, and, too often, sustainable wastewater infrastructure becomes the burden of the homeowner. As a result, throughout rural America, straight-piping, failing septic systems, and treatment systems that pour sewage into yards and homes are common.

Who is affected? Mainly Black, Indigenous, migrant and poor white communities. Climate change is making things worse in areas where there are rising water tables, melting permafrost and failing infrastructure. The health impact is devastating; in 2017, I partnered with tropical disease experts at Baylor College of Medicine on a study that found rampant hookworm in rural Alabama. My fear is that the next pandemic will emerge from right here in Lowndes county.

There is no simple solution, but to start, we need to change the engineering paradigm by including affected residents in the process of designing effective and affordable sanitation systems. Collaborative action – between communities, engineers, governments and NGOs – is crucial to ensuring that all Americans have access to clean water and soil.

Catherine Coleman Flowers is an environmental activist bringing attention to the problem of inadequate waste and water sanitation infrastructure in rural communities. A 2020 MacArthur fellow, she is the author of Waste: One Woman’s Fight Against America’s Dirty Secret

How to break our addiction to air travel

Look to the lessons of 2020 By Kim Cobb

What insights does 2020 provide about our long overdue transition away from fossil-fueled air travel? First, let’s be clear – this is not the future that #flyingless advocates hoped for. In the low-carbon future of our dreams, we can zip across wide distances via high-speed trains and run straight into the arms of our loved ones upon arrival. We can crowd into packed conference halls with colleagues from our region, while we connect with farther-flung colleagues via virtual platforms.

We’ll look back on 2020 as a screen-filled dystopia that placed new value on in-person connections. By the same token, it will be nice to know that going forward, we have a viable, remote alternative for those trips where the climate costs, and associated injustices, outweigh the value for us as an individual. For me, that would be almost all flights. But going forward, it’s an urgent question for everyone to ask themselves.

Kim Cobb is the Georgia Power chair and professor in the School of Earth and Atmospheric Sciences and director of the global change program at the Georgia Institute of Technology

How to reduce the plastic choking our planet

‘Strive for consistency, not perfection’ By Rachel Garcia

Many people think that recycling is the answer to America’s plastic problem, but the truth is that only 9% of plastic waste gets remade into something new. The rest is sitting in a landfill or the oceans, polluting our planet and even breaking down into microplastics that enter our bodies.

Many people assume that to make a difference, you need to change everything about your lifestyle, but smaller actions do add up. Put a canvas or reusable tote filled with fabric produce bags in your trunk or near your door. Try to buy loose produce instead of produce wrapped or boxed in plastic packaging. Instead of buying new Tupperware, take a look at your own pantry for the glass jars right at your fingertips! Empty tomato sauce, pickle or jelly jars can easily become clear, organized storage if you soak off the labels with baking soda and vinegar.

To create lasting habits, don’t make drastic changes overnight. The key to reducing your plastic waste is to strive for consistency, not perfection.

Rachel Garcia is the owner of Dry Goods Refillery, a plastic and package-free pantry in Maplewood, N ew Jersey

Most viewed

Covering a story? Visit our page for journalists or call (773) 702-8360.

New Certificate Program

Top stories.

- Inside the Lab: A first-hand look at University of Chicago research

- Scav reflections: “for the love of the pursuit and the joy in the attempt”

- W. Ralph Johnson, pre-eminent UChicago critic of Latin poetry, 1933‒2024

- Big Brains: All Episodes

Why Some Nations Prosper and Others Fail, with James Robinson (Ep. 37)

A leading University of Chicago scholar explains why some nations fall into poverty while others succeed.

It’s a simple question to ask, but seems impossible to answer: What causes one nation to succeed and another to fail? What exactly are the origins of global inequality?

There are few people who have spent more time trying to answer this question than Prof. James Robinson. Robinson’ first book, Why Nations Fail, was an international best-seller. It laid out in clear and stark terms what the origins of prosperity and poverty really are. Now, he’s written a sequel, The Narrow Corridor , which further explains what ingredients you need to create a prosperous nation.

Subscribe to Big Brains on Apple Podcasts , Stitcher and Spotify . (Episode published December 2, 2019)

Recommended:

- New book examines why liberty blossoms in some states but wilts in others

- The Narrow Corridor : the fine line between despotism and anarchy— Financial Times

- The Upside of Populism —Foreign Policy

- James Robinson: “Everywhere people are interested in liberty”— Prospect magazine

- Pearson Global Forum in Berlin to focus on deconstructing conflict

Transcript:

Paul Rand: There are certain books that are so important you see them everywhere.

James Robinson: Maybe you know the book Guns, Germs and Steel?

Paul Rand: Guns, Germs and Steel by Jared Diamond is certainly one of those books. It redefined the way we thought about human history by arguing that some nations succeeded while others failed because of where their geographic locations and natural resources.

James Robinson: So Jared Diamond, you know, he's a very good friend of mine. And we actually edited a book together once. So he's been a great inspiration for me on many levels. But I actually think, fundamentally, his explanation of human history is wrong. It’s not about exogenous factors that condemn certain societies to poverty or bless them with prosperity. It’s really about how humans themselves organize their societies that makes the difference.

Paul Rand: James Robinson is a prominent political scientist and economist at the University of Chicago as well as the director of the Pearson Institute for the Study and Resolution of Global Conflicts. He’s also the author of his own well-renowned book, Why Nations Fail , which gives a very different view of human history. One that tells a story about how our political and economic institutions have determined why nations succeed.

James Robinson: I mean, I've given probably a hundred talks about Why Nations Fail at this point. And what I see is that this notion of extractive and inclusive institutions is very simple, and it resonates with people because it gives them a language for helping people kind of process all this information that they have in the world, but they don't really know how to organize it or order it.

Paul Rand: Why Nations Fail was a huge success. Now, Robinson and his co-author Darren Acemoglu have written a sequel. It explains how and when these institutions come about and why our world looks the way it does.

James Robinson: Economists understand what generates prosperity. You know, they understand it's about investment in public goods and education and property rights and innovation. And so to me I've never been interested so much in rich countries because, like, what's curious is why is it that when everyone agrees why is that doesn't get going in Haiti or Sierra Leone? So, to me, the puzzle has always been about poor countries and about why poor countries can't take advantage of all this stuff which is in economics textbooks.

Paul Rand: From The University of Chicago this is Big Brains, a podcast about pioneering research and pivotal breakthroughs reshaping our world. On this episode, James Robinson and prosperity and poverty of nations…I’m your host Paul Rand.

Paul Rand: It’s one of those questions that’s so simple to ask but it seems too big to answer. Why do some nations fail while others succeed? There’s probably few other people on the planet who have worked harder to find an answer than James Robinson and his co-author Darren Acemoglu.

James Robinson: You know, successful countries in our view are just countries that manage to generate high levels of living standards for their people and failed countries are countries that don't, where there's mass poverty and deprivation.

Paul Rand: OK. And so when you think about it, is there a fundamental idea of things that if you had to summarize what it is that that pushes nations to fail or to succeed? How do you typically talk about that?

James Robinson: Yeah, I think that whether or not a nation succeeds or fails depends on how the people in that society themselves organize that society, organize the institutions, the rules that create different patterns of incentives and opportunities.

Paul Rand: This may sound basic, but it’s actually a radical idea. For decades, scholars have argued that what separates successful and failed nations is their geographic location, resources or culture. To illustrate why those theories don’t work, we need to go to two towns along the southern border of the US…Nogales, Arizona and Nogales, Mexico.

James Robinson: Yeah. We start the book with these what the social scientists would called natural experiments. Where you have kind of experimental like variation in the way societies are organized, holding constant cultural factors or geographical factors. So it's a powerful way of trying to show that these other types of theories that people often like can't really explain what you observe. And what really matters about Nogales, which is essentially one town with a fence running down the middle is that the northern half is in the United States and the southern half is in Mexico.

Paul Rand: North of the fence, in Nogales Arizona, people invest in businesses and houses without fear of theft by others or the government. Their kids are in school and they have relatively good incomes. South of the fence, in Nogales, Mexico, incomes drop to one-third, education rates plummet and infant mortality rises. Yet there is no difference in geography, climate and very little difference in culture on either side of the fence. So, what exactly caused the difference in living standards?

James Robinson: You know, if you thought about over the last hundred years why was Mexico so different from the US? Well, first of all, Mexico had this autocratic one-party state until extremely recently, the PRI, from the late 1920s, right the way through in the 1990s.

TAPE: The PRI was created by military elites clinging to power after winning the Mexican Revolution.

James Robinson: So there was just one hegemonic political party.

TAPE: A long period of economic growth market by authoritarian controls characterized Mexico in the 1940, 50s and 60s

James Robinson: There was no accountability. There was no political competition. There was no Democrat democracy at all. So that's part of what. What we call inclusive political institutions is about. It's about having political power broadly distributed in society so people's preferences count and it's also about the state and the capacity of the state. So, the Mexican state has just been much less able to develop capacity to provide public goods and order. And why is that? Well, you know, because it was used as a tool of patronage and politics by the one-party state. So, in our theory, the first layer, is economic institutions that create different patterns of incentives and opportunities in the economic sphere. But lying behind that is political institutions. You know, politics is the study of how societies make collective choices. And, for us, the way the economy is organized is a collective choice. The economic institutions, the rules, property rights, whatever it is that comes out of the political system. So, lurking behind economic differences must be political differences.

Paul Rand: Robinson and Acemoglu say there are two kinds of institutions, extractive and inclusive. Understanding how they work creates a useful framework for figuring out why nations succeed or fail. We’ll start with extractive institutions.

James Robinson: If I look at the specific institutions of Haiti, or Sierra Leone, or Uzbekistan, obviously the details are extremely different. You know, the way the labor market works, the way property rights to land are. So, you need a language which sort of says, okay, the details, they’re all different but actually these institutions have this one thing in common. Okay, they're extractive. And what does that mean? It means they take away people's incentives and opportunities or they concentrate incentives and opportunities.

Paul Rand: How do you take away someone’s incentives?

James Robinson: Well, you well think you know think about the security of property rights. You know, if you go to rural Haiti, property rights are very ill defined. Nobody has a proper title given by the government. There's endless disputes over boundaries over who owns what. So if you're thinking of investing and saving and building ditches, investing in your land, farming, the fact that your property rights are contestable and vague and, you know, insecure undermines your incentives.

Paul Rand: And this makes sense, right? If you live in a place where your land, home, or possesions could be and regularly are taken away by others or the government. You’re not going to have an incentive to invest. And no investment means no long term growth. Often these states concentrate the wealth of the country amongst a few at the top by extracting it from the occupants through taxes and labor.

James Robinson: So we talk about slavery or the way many colonial societies were constructed. You know, if you look at South Africa, for example, under apartheid,

Tape: Apartheid really began in 1948 but separating black Africans from the white minority had long been a policy aim. Laws made white people officially superior and the large black majority faced discrimination in every aspect of their lives.

James Robinson: where rules and regulations stop black people, you know, stop black people occupying many types of professions, stop black people owning land, pushed black people into these Bantustans.

Tape: There were separate public facilities, transport and schools. Interracial marriage was banned, many had no right to citizenship and were regarded as aliens in major cities.

James Robinson: You know, here's clear examples of how people's incentives and opportunities were stripped away.

Paul Rand: So…what do inclusive institutions look like…

James Robinson: So here's a good example of an inclusive institution, which I think sort of drives the point home. The patent system. So in the book, we have a photograph of the patent that Edison took out when he invented the light bulb. Economists know since the work of Robert Solow in the 1950s that what drives economic growth is incentives, innovation, new technologies, productivity increasing devices, machines, ideas. And so how do you get that going? Okay. Well, ideas are easy to copy. You know, I could come up with the idea for a light bulb and you could say, oh, that's a great idea, I'm going to use that to do something else. So, that's a problem from the incentive point of view because it means that if I have an idea, maybe I can benefit from it. But you can also benefit from it, too. So, the wealth that idea generates spills over every way. Right. So my private incentives are different from the social incentives. So, the idea of a patent is, by protecting your intellectual property rights, you kind of bring the private incentives closer to the social incentives. So, a patent protects your intellectual property rights and it creates incentives for innovation. But the interesting thing about the patent system in the US is that this was open to everybody. Everybody paid the same fee to take out a patent, and the state protected your intellectual property rights. It’s a very important thing, you know, it's in the Constitution, the first patent board .

Paul Rand: I didn’t know that.

James Robinson: And the first patent board was regarded as so important that Jefferson was on it. You know, Jefferson was there deciding whether or not your idea deserved the patent. If you look at who were these people who took out patents in the 19th century in the U.S., when the U.S. was becoming the world's technological leader. What's interesting about that is they come from all over the social spectrum, elites, non elites, farmers, artisans. You know, Edison, he was home schooled. His father was a roofing contractor, you know, so. So he was not an elite. And the message there is creativity, ideas, talent, entrepreneurship, it's sort of spread very widely in society. You don't know where it is, I don't know where it is, the government doesn't know where it is, you've got to create a system of rules which can harness all that latent talent. And that's this idea of inclusive institutions that create broad based incentives and opportunities. So people with ideas and talent and creativity can come to the top. And we know that's what drives innovation and productivity and prosperity. And that's what you don't have in Haiti. That's what you didn't have in Mexico. You know, you don't have a system of rules. Most people are excluded from opportunities, chances, finance, property rights, education. So that all the benefits are concentrated in the hands of a small subset of society. And that may create wealth for them, which is part of the problem, but it creates poverty for the society in which they're living.

Paul Rand: A few months ago, Robinson and Acemoglu released their follow up to Why Nations Fail, it was a book called The Narrow Corridor . That’s after the break.

James Robinson: I think that in why nations fail, we did a good job of making this connection between inclusive and extractive economic institutions and economic success and failure, and then trying to show how there was a politics lying behind that. But then then the question comes up. Okay. So, why is the world divided into countries which have extractive political institutions and inclusive political institutions? Where does that come from? You know, the current book, I think makes two contributions. One, it tries to emphasize this notion of liberty as important both in itself, but also deeply connected to economic success. So liberty is, you know, you're free in the economic sphere, in the social sphere, in the political sphere to undertake your choices, to do what you want to do without the threat of influence by other people, at least up to the extent whereby your choices don't adversely affect other people. So I think we have a fairly classical definition of liberty. But then the question is what explains these massive variations in the extent to which societies, people in different societies in the world benefit from liberty or experienced liberty? So, what are the mechanisms that lead to that or don't lead to it? And how, historically has liberty emerged in some parts the world and not other parts of the world? You know, why is there much more liberty in Western Europe than in China, for example, or in India, or why is there more liberty I would say in North America than there is in Latin America. The way we tried to think about this creation of liberty or illiberty is to say, you know, you can think of this as coming out of a balance between the power of the state and the power or the organization of society.

Paul Rand: And Robinson and Acemoglu argue that there are three kinds of states—or Leviathans as they call them—the absent leviathan, the despotic leviathan, and the shackled leviathan.

James Robinson: So a despotic leviathan is perhaps the simplest thing to think about. We characterize, say, China right the way back since the first dynasty as a despotic leviathan where the apparatus of the state and the institutions of the state completely dominated society. Another possibility, the kind of stark opposite to that would be where society dominates the state. Now, think of Yemen. You know, in Yemen, there's never really been a centralized state which has any authority over society. Society is kind of organized around kinship groups and tribes that are armed. They organize and provide public goods completely independent of the state. And that's true of many parts of the world. You know, in sub-Saharan Africa, you know think of Lebanon, think of large parts of the Philippines or Pakistan or Nepal. So that's not a strange anomaly, its presence in the modern world. And it's very prevalent historically. So we call that the absent leviathan. And so state dominates society or society dominates the state and in between, and this is the key to kind of liberty or creating what we call the shackled leviathan, the third type of state, is this balance between state and society.

Paul Rand: That balance between state and society is the narrow corridor from the book’s title…

James Robinson: Yes, it’s this sort of zone where state and society are balanced. It’s an equilibrium and it’s a contested equilibrium. You know that state institutions don't want to be controlled by society. State elites would like to not be accountable and they'd like to do what they want. And society has to force them to be accountable. But what about the other side? You know, what about going off the rails in the other direction where in some sense discontent from society about institutions throws you out of this corridor

Tape: We are going to drain the swamp

James Robinson: You know, President Trump is a sort of complicated phenomena. But it's clear that he identified a lot of discontent in U.S. society about the way things were working that other politicians didn't get and they didn't understand.

Tape: Everybody’s so angry with the democrats and so angry with the republicans that’s why he’s got the support he’s got. He’s the screw you Washington vote, that’s all he is.

James Robinson: And those are real issues, I think. Problems of this massive increase in inequality, and employment and marginalization and I think there are real social problems here and there’s disillusionment with the ability of institutions to cope with these problems. So it's a challenge to stay in the corridor and maybe that's what we're seeing now.

Paul Rand: Okay. So. So let me get a little historical with you for a moment. If we look at societies, nations falling back to arguably the Mesopotamian times. If you were going to say, here's where I start looking at studying these things. Are these things learned over time or are they forgotten over time? And we are doomed to keep learning these lessons over and over again?

James Robinson: Yeah. To me, it's not it's not really a matter of knowledge. You know, if you ask me about why did ancient Athens boom economically? I’d tell a similar story. I think the emphasis in the book is very much on persistence. We start the book by talking about this famous prediction when the Berlin Wall fell down that all the world was going to converge to liberal democracy by Francis Fukuyama.

Tape: The end of history refers to what I think still remains a question of whether that process is one that can terminate, whether that evolution finally culminates in a certain kind of civilization that in a certain sense will be the last civilization mankind will achieve because in a certain sense it’s the right one it’s the one that fits human nature in an appropriate way.

James Robinson: Yeah. But our view is that no, actually, the pattern in history is not convergence, it's divergence. China has been where it's been for to over two thousand years, Yemen, we actually know quite a lot about Yemen going back a thousand years, and it looked pretty like it does now a thousand years ago. So this is not this is not something…nobody's bouncing about. You're kind of stuck in these very different steady states. You know, these very different types of leviathan. And our story about the history of Europe or how Europe develop these types of shackled leviathan, that's also deeply historically rooted, you know, has to do with the collapse of the Western Roman Empire and the way that these Germanic tribes, which had very participatory political institutions, merged with late Roman state institutions, administrative institutions, legal institutions, fiscal institutions to kind of bring this balance between state and society together. That's the roots of this thing. That's a long time ago. So actually, there's a lot of what social scientists call path dependence in this process.

Paul Rand: Path dependence?

James Robinson: That once you get a particular constellation of institutions in a society, that does tend to reproduce itself. So that's why you have this divergence, not convergence. Now, of course, it's also true that societies do go out to the corridor. So particularly we talk about the German case. So I'd mentioned the Germanic tribes. So you might think, okay Germany, Germany should be in the corridor and it is in the long run. But also, if you think about German history, there's clear moments where they went outside to the corridor, think about the Nazi state. You know, for 15 years, there's a bottom up push out of the state. You know, that's an interesting example of disillusionment with institutions, the inability of institutions to resolve conflicts, to resolve economic problems, the crisis of the depression and the hyperinflation. What I find super interesting is that you get these very unstable dynamics that can throw a society out of the corridor. But when they crash. You get back into the corridor. Germans after 1945 had a a kind of common understanding of how things were going to work and how institutions ought to be structured. And they were able to recreate this shackled leviathan. They had a blueprint for creating this shackled leviathan. Understanding how you did that from the past, which you know, which nobody in Haiti or Sierra Leone has.

Paul Rand: I can’t imagine that there’s not a listener paying attention to this right now that’s not thinking about in the U.S. And you mentioned that there are certainly some evolutions that are going on and some things that President Trump identified that that arguably got exploited. Do you look at this and say that we’re moving toward an absent or despotic state right now in the United States, and that's something we should be concerned about?

James Robinson: I don't think so, because I think the history of the U.S., you know, going back to this kind of historical path dependence, the history of the U.S. suggests that the institutions are capable of responding to these challenges. People have to make compromises, they have to make new deals, they have to make coalitions. And I think that's what has to happen in the U.S. now. And I think the past suggests there's some reason to be optimistic that that will happen. You know, I think Democratic politicians are probably woken up at this point and realize there are a lot of problems that they weren't very aware of. And I'm you know, I'm even in the Brexit context, for example. I mean, I'm English, you know, and in the Brexit context, I always think, people say, oh, what a terrible thing this referendum was and how David Cameron was so crazy. But actually, I think the opposite is true. You know, what the referendum showed is that there is deep seeded kind of animosities, you know, all those deep seeded discontent about the way many things work that the political elites were not aware of.

Paul Rand: Now they are.

James Robinson: Absolutely. And that's a good thing.

Paul Rand: And it is you think about it and we've talked about that. You do travel the world and you lecture. You consult. You speak. Are people looking at you and saying, I want to figure out in my country what I should be learning from? And we bring in economists. We bring in politicians. We bring in scientists. Are you finding that you're consulted and saying, help me understand as I am looking to evolve my society?

James Robinson: Yeah, I do not consult, actually. In the sense of, you know, governments pay me to come and tell them what to do. I had one experience of that and I didn't enjoy it.

Paul Rand: Why didn't you enjoy it?

James Robinson: Because I felt everybody was over promising. You know, my view of the world is if you want to understand how to improve economic performance in Colombia, for example, we have these general ideas about institutions, inclusive institutions. You have to make institutions more inclusive. But as soon as you're in the business of trying to give policy advice, then all the details become extremely significant. So what you have to do in Colombia is going to be extremely different from what you have to do in Sierra Leone or what you have to do in Argentina. And then you need a lot of, you know, thick knowledge of those societies. And so I think this business of running around the world telling, Kazakhstan what to do is a fool's game. And I felt extremely uncomfortable personally to be involved in that. And I've never done it ever since. Actually going and telling people about my ideas and talking to them…

Paul Rand: They can do with it what they will.

James Robinson: Yes. And for me, I find that incredibly interesting. You know, I want to I think these general concepts are useful, but I always tell them, you know, OK, if you want to think about how to make institutions more inclusive, then you need to start thinking about all these details and trying to identify what's extractive or what works and what doesn't work and what's the politics around that. And how do you solve these problems.

Paul Rand: Well, let me ask you, this is not a consulting assignment, but if you're with students and the question came up with all the knowledge that you have and the question was, well, how do you develop if you're going to start with a clean sheet of paper and design, the perfect society? How would you think about doing that?

James Robinson: You know, one of the things that I personally find very enjoyable is all the sort of diversity in the world. What impresses me about the history of humanity is the incredible diversity of the types of societies that humans have created. I think there's fundamental political and economic problems that people have to solve in these societies, and they solve them in different ways. You know, because humans are creative and they're innovative and it's interesting if you think about like Homo-sapiens, Homo-sapiens spread all over the world without speciating. They populated Greenland, but there wasn't like a Homo-Greenland-ious or whatever. You know, well how did they do that? How did they adapt to such a totally different environment without speciating? You know, they invented igloos and ice fishing. So that seems like kind of a wacky example but I think it tells you a lot about why social science is interesting. You know, all those different ways you can do things, cultures and everything, you can still have prosperity. You know, you can still have public goods. You can still have investments. So all of that variation is consistent with having basic inclusive societies. You know, for us, that's the story. That's the big story is human innovation and creativity. And humans create these very different types of societies and some of them diffuse and spread and others don't. And that’s the pattern. So I think, look, what we would like to do is probably write a book where we could convince people that this was the right way to think about things. I think we've done bits and pieces of that in these two books, but I don't think we're quite there yet. We don't have quite the right way of doing that yet.

Paul Rand: Your book, Why Nations Fail was an international bestseller. Hopefully your new one will follow suit. As you write these books, why do you think that they get the attention they do. What do you. think you hope people get something out of it? What is it that you were hoping for? How do you think that's happening? Where's the attraction?

James Robinson: You know, there's enormous academic research but it’s so impenetrable for non-academics. You know, the language is impenetrable? The methods are impenetrable. But often, you know, the ideas can be said in quite a simple way. And I think Darren and I, we sort of read everything. We've always been inspired by political science, by anthropology, by reading history, by social, you know, by all sorts of things. One of the reasons we wrote why nations fail is that many of the things that we found inspiring or stimulated research we were never able to include in an academic paper because that's just inappropriate. You know, it's not scientific or whatever. And we thought, well, you know, gosh, all these things have inspired us, you know, and helped us think about the world. Maybe they'll inspire other people to. And it's been surprisingly we never thought the book was going to be successful, to be honest with you. We thought we'd have a shot at it. But we were expecting to fail dismally. But it's been it's been incredibly rewarding.

Paul Rand: I would argue that that the simplicity and clarity of in or outside the corridor is also a compelling and hopefully understandable concept that will push this conversation even to a next degree.

James Robinson: Well, we're hoping so, too, but we'll have to wait and see.

Episode List

How to manifest your future using neuroscience, with James Doty (Ep. 135)

‘Mind Magic’ author explains the scientific research on how to train our brain to achieve our goals

Why we die—and how we can live longer, with Nobel laureate Venki Ramakrishnan (Ep. 134)

Nobel Prize-winning scientist explains how our quest to slow aging is becoming a reality

What dogs are teaching us about aging, with Daniel Promislow (Ep. 133)

World’s largest study of dogs finds clues in exercise, diet and loneliness

Where has Alzheimer’s research gone wrong? with Karl Herrup (Ep. 132)

Neurobiologist claims the leading definition of the disease may be flawed—and why we need to fix it to find a cure

Why breeding millions of mosquitoes could help save lives, with Scott O’Neill (Ep. 131)

Nonprofit's innovative approach uses the bacteria Wolbachia to combat mosquito-borne diseases

Why shaming other countries often backfires, with Rochelle Terman (Ep. 130)

Scholar examines the geopolitical impacts of confronting human rights violations

Can Trump legally be president?, with William Baude (Ep. 129)

Scholar who ignited debate over 14th Amendment argument for disqualification examines upcoming Supreme Court case

What our hands reveal about our thoughts, with Susan Goldin-Meadow (Ep. 128)

Psychologist examines the secret conversations we have through gestures

Psychedelics without the hallucinations: A new mental health treatment? with David E. Olson (Ep. 127)

Scientist examines how non-hallucinogenic drugs could be used to treat depression, addiction and anxiety

Do we really have free will? with Robert Sapolsky (Ep. 126)

Renowned scholar argues that biology doesn’t shape our actions; it completely controls them

Subscribe to the Big Brains Insider newsletter

Shared Prosperity: A New Goal for a Changing World

- This page in:

Inequality often weakens a nation's economy and social stability.

STORY HIGHLIGHTS

- The World Bank Group will be promoting shared prosperity, or inclusive economic growth.

- A new Shared Prosperity Indicator will track income growth among a nation's bottom 40 percent.

- The new indicator marks a departure from how economists have traditionally measured a country's progress.

The World Bank Group’s mission to help free the world of poverty has been translated into two clearly articulated goals. The first goal is a moral imperative to end extreme poverty for the 1.2 billion people who continue to live with hunger and destitution.

Along with lingering poverty, groups of people are fall behind in some developing countries that enjoyed strong economic growth over the past decade – in many cases with widening inequality as a result. The second goal established by the World Bank Group is therefore to promote shared prosperity.

Jaime Saavedra-Chanduvi , the Bank’s Acting Vice President for Poverty Reduction and Economic Management, explains why the institution decided to focus on shared prosperity, and how this will guide its work in coming years.

What does the term “shared prosperity” mean for the Bank?

The shared prosperity goal captures two key elements, economic growth and equity, and it will seek to foster income growth among the bottom 40 percent of a country’s population. Without sustained economic growth, poor people are unlikely to increase their living standards. But growth is not enough by itself. Improvement in the Shared Prosperity Indicator requires growth to be inclusive of the less well- off.

Why is the Bank focusing on shared prosperity at this time?

We know that economic growth is sometimes accompanied by greater inequality and social exclusion. Our focus on shared prosperity reflects the fact that many countries are seeking rapid and sustained increases in living standards for all of their citizens, not just the privileged few. While ending extreme poverty by 2030 is a clear target and priority, our mission is not just about the poorest developing countries. We care about poor people wherever they are.

Jaime Saavedra-Chanduvi

Does the shared prosperity goal imply reducing inequality by redistributing wealth?

No. We need to focus first on growing, as fast as possible, the welfare of the less well off. But we’re not suggesting that countries redistribute an economic pie of a certain size, or to take from the rich and give to the poor.

Rather, we’re saying that if a country can grow the size of its pie, while at the same time share it in ways that boost the income of the bottom 40 percent of its population, then it is moving toward shared prosperity. So the goal combines the notions of rising prosperity and equity.

We’ll be tracking growth in incomes of the bottom 40 percent, and due to the fact that that this will be done alongside national income growth monitoring (which countries already do), countries will see directly how the less well-off are faring.

We do not use as an indicator of the shared prosperity goal the growth of the bottom 40 percent relative to the average growth rate, because there are periods in the development process when incomes of the poor are rising fast, and that is a good outcome even if there is some increase in inequality. But we also recognize that steady increases in inequality are not socially and politically sustainable over long periods.

It’s a fact that no country has transitioned from middle to high-income status with high levels of inequality. A persistent rise in inequality (or being stuck at high levels of inequality) will ultimately limit income growth of the less well-off and, eventually, limit economic growth itself.

How can the new Shared Prosperity Indicator measure progress over time?

Tracking the incomes of the bottom 40 percent of a nation’s population is a departure from how economists have traditionally measured progress – by focusing mainly on growth in the gross domestic product (GDP) per capita.

The assumption in the past was that a growing GDP would trickle down to the poor – well, now we know that’s not always the case. The Shared Prosperity Indicator will instead take the direct route of measuring income growth of those we are concerned about: the less-well off.

What will it take for a country to achieve shared prosperity?

The path to shared prosperity for a country will depend on both context and time. There are many pathways to shared prosperity, and they often complement one another. Plus, different societies assign specific roles to the government, firms, civil society and citizens in general. Let me mention a few examples.

First, prosperity can be broad-based if growth generates jobs and economic opportunities for all segments of the population. The private sector is typically the main engine job creation, but the government plays a critical role by implementing policies and regulations that promote a favorable environment to maintain high investment rates, and by investing in labor skills needed to build a modern and dynamic workforce.

However, the pattern of growth has to be such that it generates income opportunities for the poor. So the poverty impact of natural resources-based growth that does not pull the rest of the economy will be very different than growth sustained by agricultural productivity increases, for example.

Second, there is a need for a healthy and stable “social contract” in every country that commits to investments that improve and equalize opportunities for all citizens.