Click through the PLOS taxonomy to find articles in your field.

For more information about PLOS Subject Areas, click here .

Loading metrics

Open Access

Peer-reviewed

Research Article

Understanding the impacts of health information systems on patient flow management: A systematic review across several decades of research

Roles Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Resources, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing

* E-mail: [email protected]

Affiliation Department of Human-Centred Computing, Faculty of Information Technology, Monash University, Melbourne, Australia

Roles Conceptualization, Supervision, Writing – review & editing

Roles Supervision, Writing – review & editing

Affiliation Office of Research and Ethics, Eastern Health, Melbourne, Australia

Affiliation Monash Centre for Health Research and Implementation, Monash University, Melbourne, Australia

- Quy Nguyen,

- Michael Wybrow,

- Frada Burstein,

- David Taylor,

- Joanne Enticott

- Published: September 12, 2022

- https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0274493

- Peer Review

- Reader Comments

Patient flow describes the progression of patients along a pathway of care such as the journey from hospital inpatient admission to discharge. Poor patient flow has detrimental effects on health outcomes, patient satisfaction and hospital revenue. There has been an increasing adoption of health information systems (HISs) in various healthcare settings to address patient flow issues, yet there remains limited evidence of their overall impacts.

To systematically review evidence on the impacts of HISs on patient flow management including what HISs have been used, their application scope, features, and what aspects of patient flow are affected by the HIS adoption.

A systematic search for English-language, peer-review literature indexed in MEDLINE and EMBASE, CINAHL, INSPEC, and ACM Digital Library from the earliest date available to February 2022 was conducted. Two authors independently scanned the search results for eligible publications, and reporting followed the PRISMA guidelines. Eligibility criteria included studies that reported impacts of HIS on patient flow outcomes. Information on the study design, type of HIS, key features and impacts was extracted and analysed using an analytical framework which was based on domain-expert opinions and literature review.

Overall, 5996 titles were identified, with 44 eligible studies, across 17 types of HIS. 22 studies (50%) focused on patient flow in the department level such as emergency department while 18 studies (41%) focused on hospital-wide level and four studies (9%) investigated network-wide HIS. Process outcomes with time-related measures such as ‘length of stay’ and ‘waiting time’ were investigated in most of the studies. In addition, HISs were found to address flow problems by identifying blockages, streamlining care processes and improving care coordination.

HIS affected various aspects of patient flow at different levels of care; however, how and why they delivered the impacts require further research.

Citation: Nguyen Q, Wybrow M, Burstein F, Taylor D, Enticott J (2022) Understanding the impacts of health information systems on patient flow management: A systematic review across several decades of research. PLoS ONE 17(9): e0274493. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0274493

Editor: Yong-Hong Kuo, University of Hong Kong, HONG KONG

Received: May 17, 2022; Accepted: August 28, 2022; Published: September 12, 2022

Copyright: © 2022 Nguyen et al. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Data Availability: All relevant data is provided in the article and in the supporting file S3. Copies of the included studies are freely available online.

Funding: QDN was supported by a Ph.D. scholarship jointly funded by the Monash University Graduate Research Industry Partnership (GRIP) program and by Eastern Health. The Funders of this work did not have any direct role in the design of the study, its execution, analyses, interpretation of the data, or decision to submit results for publication.

Competing interests: No authors have competing interests

1. Introduction

Patient flow refers to the progressive movement of patients through different units or departments of the care setting. The aim of patient flow management is to provide safe and efficient patient care while assuring the best use of resources [ 1 ]. Hospitals around the world have undertaken several efforts and strategies to tackle patient flow problems and to provide high-quality care at the right time and right place. Meanwhile, there is an extensive stream of research reporting methods and interventions addressing patient flow problems. A recent umbrella review [ 2 ] found that over 25 different interventions have been used by hospitals around the world to solve the overcrowding issues in the emergency department (ED). However, previous studies focused primarily on interventions for a single, isolated hospital unit or ward with ED being the most frequently mentioned [ 3 , 4 ]. While many systematic reviews related to patient flow interventions have been done, a summary of these systematic reviews shows that most of these reviews have focused on traditional, non-IT interventions such as triage, streaming, and fast track. Systematic reviews on using health information systems (HISs) to tackle patient flow problems exist; however, they are often limited to a single specific system, such as computer provider order entry (CPOE) system [ 5 ]; methods such as computer simulation modelling [ 6 ]; or measures such as length of stay (LOS) [ 7 ].

HISs have been adopted by health providers to improve patient flow in various healthcare settings. For example, in emergency care, the automatic push notification system was used to address ED congestion, reduce LOS, and decrease patient load by providing updated information and improving patient navigation [ 8 ]. Dashboard systems were adopted to coordinate ambulance services and improve access to emergency services across multiple hospitals [ 9 ]. HISs provides data about ED visits which were used to create a robust prediction about hospital admissions and increase logistical efficiency [ 10 ]. In addition, Blaya et al. [ 11 ] investigated the use of HISs in improving access to laboratory results and the quality of care. These are a few examples illustrating the impacts of HISs on patient flow management.

In recent patient flow research, it has been suggested that utilising advanced data analytics techniques for patient flow management can be achieved by adopting HISs. For example, Rutherford et al. [ 12 ] claim that data analytics is essential in achieving improvement in systematic-wide flows through its capabilities in matching patient demand and hospital supply. Real-time demand capacity has been successfully implemented in many healthcare organisations to predict and match supply and demand [ 13 ]. Similarly, Berg et al. [ 14 ] called for a shift in the research paradigm from predicting and controlling to analysing and managing to achieve better flow outcomes. This can be done through the application of information technology in analysing data to proactively manage patient flows. Despite the rich tradition of inquiry in research about the use of HISs in patient flow management, to date, to the best of our knowledge, no systematic review has been conducted to assess the impacts of a broad range of HISs on patient flow management, highlighting an evidence gap in the literature. Therefore, a systematic review of this topic will provide more complete insights as to how HISs have been adopted for and impacted patient flow management practice.

2. Objectives

This systematic literature review aimed to examine and summarise information from published studies on the use of HISs in healthcare settings to manage and improve patient flows. We are interested in exploring what information systems have been adopted for managing patient flow and solving flow problems such as blockages, delays, and overcrowding, and their effectiveness. We examined studies that focused on department-level (e.g., ED), hospital-wide, and network-wide interventions. Particularly, our objectives are to provide critical analysis on:

- Study characteristics: Chronological and geographical distribution of the studies, study settings, and research designs.

- Study contents: What types and features of information system have been used for patient flow management, their results and effectiveness on patient flow outcomes.

3. Research questions

This review addresses the following research questions:

- What HISs have been used for hospitals’ patient flow management?

- What are the impacts of HISs on patient flow outcomes?

- In what ways, have HISs been used to manage patient flow?

4.1 Search strategy

We searched for peer-reviewed journal articles published in English from MEDLINE and EMBASE via Ovid, CINAHL, INSPEC, and ACM Digital Library from the earliest date available to February 2022. In addition, we examined the reference lists of the search results to retrieve further eligible papers. The search was conducted from June 2020 to July 2020 and then re-run in February 2022 before the data extraction process.

With the assistance of a subject librarian, we developed a systematic search strategy for this review ( S1 File ). To obtain the most comprehensive search results, we employed medical subject headings (MeSH) keywords when they are available in combination with free text keywords from the PICOS framework. We combined the following terms ( Table 1 ) in our search for relevant studies.

- PPT PowerPoint slide

- PNG larger image

- TIFF original image

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0274493.t001

4.2 Eligibility

Table 2 specifies the inclusion and exclusion criteria used in the title and abstract screening process for this review.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0274493.t002

We included studies that described the impacts of HISs that were actually implemented and adopted for managing patient flow or solving patient flow problems. We excluded papers describing prototype systems, systems that were not implemented in practice or papers without real impacts of HISs on patient flow management such as those just reporting simulated results, simulation tests, or prediction models. Studies that focused on measures such as length of stay (LOS), and waiting time for clinical purposes without any relation to or discussion of patient flow management purposes were also excluded from this review.

Type of studies.

Apart from excluding simulation studies and review papers, we imposed no restrictions on the study’s design or publication date as long as the studies examined the effects of HIS on patient flow management.

Participants.

We included studies that were conducted in various healthcare settings including teaching hospitals, specialist hospitals and general hospitals (both public and private) and clinical centres. As long as the studies were conducted in these settings, we imposed no restrictions on the number of departments, units or wards involved. We also selected studies that addressed patient flow management at the network level, i.e., between different hospital sites and hospital centres. Studies investigating interventions in services not directly related to patient flow and patient access (such as financial services or insurance) were excluded from our review.

Type of intervention.

Health information system is a broad concept and hospitals generally adopt and use several types of information systems to manage their operations. In this review, we selected studies that addressed any type of computerised information systems that have been implemented and had impacts on patient flow outcomes. We also excluded paper-based information management systems, personal digital assistance devices, and medical tools such as surgery robots, CT scanners, heart rate measuring devices.

4.3 Study selection

To assist the selection of eligible studies for this review, we used the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines with four key phases [ 16 ].

Initially, the first author searched through the pre-identified online databases by using combinations of the keywords to identify related studies. Duplicates were subsequently removed by using a tool called Covidence [ 17 ] and manually double checking by the first author. In the second step, two reviewers scanned the abstract of all studies to remove irrelevant or ineligible studies based on the predefined inclusion and exclusion criteria. The remaining studies went into the third step in which two reviewers assessed the full-text studies and further eliminated irrelevant papers. The final phase involved extracting data from included studies. We endeavoured to look for full-text files of the eligible papers in all resources available including using intra-library service to retrieve as many as possible

4.4 Data extraction and quality assessment

Information from the papers was extracted in the final list using an electronic data extraction form. Each study was given a unique identification number to ensure a consistent way of identifying studies between the two reviewers. The following data were extracted: authors, journals where the studies were published, year of publication, hospital’s country, the study settings, study objectives, study design, description of the information systems used, factors affecting the adoption of HISs for patient flow management, the effects of HISs on patient flow outcomes, study results, study limitation and research gaps ( S4 File , Example of data extraction form).

The GRADE [ 18 ] approach was adopted to assess the overall quality level of the evidence based on their design. GRADE approach provides particular useful guidelines for assessing health technology studies with heterogeneous study designs. Using the guidelines, the quality of evidence would be assessed as follows:

- High quality for randomized trial studies without serious limitations

- Low quality for observational studies

- ‘0’ level of quality for studies where quality is not assessable such as expert opinion and studies without objective evidence.

4.5 Analytic frameworks

We adopted literature review and expert opinion to develop frameworks that describe types of HISs, their functional capabilities, and associated benefits ( Table 3 ). We also used the conceptual model of Donabedian [ 19 ] as a framework for the analysis on patient flow outcomes. Donabedian’s model categorises care quality into three groups: structure, process, and outcomes.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0274493.t003

The literature search returned 5996 studies and the removal of duplicates reduced the number to 5095. After the first level of screening in which we screened the titles and abstracts and applied the exclusion criteria, 4824 studies were removed. We then proceeded to screen the full-text of 271 studies and 231 of them were excluded. In addition, four studies were added to the final pool through the reverse snowballing technique. Details of the screening process is summarised in Fig 1 , following the PRISMA flow diagram [ 16 ].

From : Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG, The PRISMA Group (2009). Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses: The PRISMA Statement. PLoS Med 6(7): e1000097. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed1000097 .

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0274493.g001

We included 44 studies for our systematic review. The included studies reported mixed impacts of HISs on patient flow management, which can be categorised as follows:

- 33 studies reported positive impacts [ 9 , 20 – 51 ]

- 7 studies reported negative impacts [ 52 – 58 ] and 4 studies reported no impacts of ISs [ 59 – 62 ]. However, among the seven studies with negative impacts, two [ 55 , 58 ] found that the negative effects were temporary and the patient flow measures returned back at pre-implementation baselines.

5.1 Types and features of the HIS

The included 44 studies reported the impacts of 17 different types of HIS on patient flow: eight EHR systems, eight EMR systems, seven patient tracking systems, four computerised provider order entry systems (CPOE), three patient flow dashboard systems, three departmental information systems including ED (1) and Radiology (2), and one each for workflow management, admission prediction, documentation management, patient scheduling, medical prescribing, patient discharge management, patient referral management system, bed management, consultation management, clinical information management, and Asthma management. Table 4 summarises details of the study site and publication profile of the included studies (publication year, country and study settings).

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0274493.t004

Research on the application of HISs to patient flow management can be dated back to the 1980s; however, it has gained prominence over the last decade. A majority of included studies were published in the period 2011–2020 (63.6%), compared to 29.5% of the 2001–2010 period and 6.8% of the 1988–2000 period. In addition, most of the studies selected for this review were published in developed countries where their governments have implemented promotional programs to increase the adoption of HISs in the healthcare sector. The number of studies from the USA was the highest with 24 studies, followed by Australia with nine studies. Canada and South Korea contributed three and two studies, respectively. One study was conducted in each of the followings: England, Italy, Japan, Portugal, Uganda, and Taiwan.

In terms of settings, 20 of the reviewed studies discussed the impacts of HIS interventions at the department level, while eleven studies addressed hospital-wide level and three studies address network-wide level. Within the department level, 15 studies focused on EDs, three in Radiology and two in Paediatrics. Studies focused on hospital-wide patient flow when they include the coordination between several departments or units. For example, Westbrook et al. [ 51 ] discussed the impacts of CPOE on the flow of patients between ED and Pathology departments in Australian hospitals. In addition, we found that four studies described the impacts of HISs on patient flow across hospital networks [ 9 , 31 , 39 , 42 ]. Fig 2 depicts where the reported HIS were studied in the care continuum and the number of studies.

The numbers in the circles correspond to the number of relevant studies reviewed.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0274493.g002

Specific functions of the 17 types of HIS that were described in the 44 studies included patient or event tracking (12 studies), clinical documentation management (12 studies), order entry (8 studies), patient registration (3 studies). Bed management, decision support, discharge management, patient flow reporting and prescription management were each included in three studies. Alert, disease detection, picture archiving, staff performance management, referral management, and reminder, were each discussed in one study. Almost all of the included HISs had the capability to integrate data from other systems. Twelve studies did not describe system features. Details of the HIS features and reported benefits are provided in S2 File .

5.2 Impacts on patient flow measures

Table 5 provides a summary of how key patient flow measures were grouped into three categories based on Donabedian model [ 19 ] and the number of studies that included these measures. Details of the included studies and HISs’ impacts on patient flow measures are provided in S3 File , Characteristics of all included studies and their findings.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0274493.t005

Impacts on outcome measures.

Outcomes measures were the most studied measures in the included papers. This is not surprising because health outcomes are the end products of care and the target of health interventions. Studies examined two main types of outcome measures: individual outcomes and organisational outcomes. Almost all studies focused on individual outcome measures in which time-related measures included LOS (25), waiting time (13), treatment time (6), test turnaround time (TAT) (6), and boarding time (2). The effects of HISs on these time related measures were mixed. With regard to LOS, following the use of HISs: 14 studies [ 22 – 25 , 29 , 32 , 33 , 36 , 38 , 39 , 41 , 43 , 45 , 51 ] reported a decrease in LOS, 7 studies [ 9 , 52 – 55 , 57 , 62 ] reported an increased LOS and 4 studies [ 58 – 61 ] found no difference. While most of these studies measured LOS in the ED, five studies [ 25 , 39 , 41 , 43 , 45 ] measured inpatient LOS and two studies [ 23 , 59 ] reported changes in patient LOS at paediatrics centres. The ED LOS was not consistently defined. ED LOS was defined as the difference between ED exit time and the recorded arrival time [ 52 ]. Whereas some studies [ 22 , 59 ] calculated detailed components which constitute the total LOS including time from arrival to triage, arrival to doctor, doctor to disposition, most other studies just reported the mean LOS.

Similarly, 14 studies reported impacts of HISs on waiting time. The results were mixed with 10 positive changes (reduction in waiting time), 2 negative and one with no statistically significant difference. Waiting time measures included waiting for the doctor, waiting for medical treatment, waiting for consultation and for examination. Three studies [ 43 , 58 , 59 ] examined impacts of EHRs on patients waiting for doctor time. In one study [ 59 ], investigators measured the mean patient flow time in a paediatric practice in the USA and found that although the mean patient flow time increased from 56.24 min to 81.43 min one month after the EHR implementation and to 64.60 min 12 months later, patients’ waiting time (check-in to front desk and front desk to triage) actually dropped down by 1.51 and 9.33 min. Their findings suggested the EHR led to more positive results than negative because it reduced waiting for administrative works, allowing more time to be spent on treatment activities. Two studies [ 54 , 56 ] reported negative impacts of HIS on the waiting time of ED patients. Gray and Fernandes [ 54 ] examined the adoption of CPOE in an ED in London Health Sciences Centre with around 100,000 patients per year to determine that CPOE caused an average increase of 5 min in waiting time. A more significant increase in waiting time from 40 to 78 min was observed in a 54,000 patient-per-year ED with the EMR system by Mohan, Bishop, and Mallows [ 56 ].

Treatment time is an important component of LOS and it directly influences health outcomes. However, in this review, we could only identify six studies that used this measure to assess the effectiveness of HIS. Unfortunately, these studies did not provide detailed explanation how the HIS affected treatment time. Three studies [ 22 , 23 , 44 ] found that health providers reduced treatment time when using an ED information system and a patient tracking system for their practice. The patient tracking system was used in a paediatric centre with 24,000 visits annually and it reduced the time of faculty paediatricians spent in Exam room from 11.33 to 6.53 min [ 23 ]. Meanwhile Baumlin et al. [ 22 ] determined a dramatic decrease by 1.90 h in the doctor-to-disposition time after an ED information system was implemented. Two studies about the EHR systems [ 58 , 59 ] and an asthma management system [ 60 ] did not identify a significant difference in treatment caused by the interventions.

TAT is another time-related measure and it was investigated in 6 studies [ 21 , 22 , 38 , 41 , 48 , 51 ]. TAT is defined as the time lapse between when the test is ordered and when the result is available [ 41 ]. Four studies [ 21 , 22 , 39 , 41 ] examined TAT of the radiology examinations and laboratory results; one study [ 48 ] investigated TAT of housekeeping services and one study [ 51 ] reported pathology examinations. All of the studies reported impressive reductions in TAT after the implementation of a HIS. For example, Nitrosi et al. [ 41 ] noted a decrease in the mean chest exam TAT from 33.9 to 9.62 h.

Finally, boarding time is an important patient flow measure that is often referred to as access block or bed block and it is a main patient flow problem [ 63 ]. Two studies [ 22 , 52 ] examined this measure although Pyron and Carter-Templeton [ 43 ] investigated provider discharge-to-nurse discharge time, which can be related to boarding time, but they did not explain or describe how this measure was calculated. Baumlin et al. [ 22 ] reported that the use of an ED information system reduced boarding time for the patient by 28% from 6.77 h to 4.90 h. By contrast, Feblowitz et al. [ 52 ] noticed an increase in the mean boarding time per patient from 211.2 min to 221.4 min in the long term (1 year after the implementation of an electronic documentation system) in an ED. However, neither study provided a causal relationship between HIS implementation and the changes in boarding time.

In addition to time-related measures, included studies also investigated other important individual outcomes including: four studies on the percentage of patients who left without being seen (LWBS), three studies on patient satisfaction, one each for mortality rate, and readmission rate. LWBS was studied in the ED setting. Three studies [ 54 , 56 , 61 ] reported increases of LWBS percentage with the most significant increase being reported in the study about a CPOE system from 24.3% to 42.0% [ 54 ], while Jensen [ 33 ] determined a reduction of 7.6%, but this study did not provide any subjective evidence. Patient satisfaction was measured in three studies with one positive result [ 35 ], one negative [ 62 ], and one neutral result [ 58 ]. The EHR system was found to reduce ED patient satisfaction because it increased LOS; however, the negative impacts lasted for only eight weeks before returning to the baseline from before the intervention implementation [ 62 ]. One study reported that the use of a patient discharging system [ 37 ] was associated with improvement in LOS for early discharge patients without higher rates of readmission. In another study, Inokuchi et al. [ 32 ] investigated the impacts of a newly-developed EMR system on the mortality rate at 28 days after hospitalisation and found no changes resulting from the intervention, which is a positive outcome.

Apart from the patient-related outcome measures above, studies also examined organisational outcomes including four studies about hospital costs, and one each for staff satisfaction, film saving and staff stress level. Three studies [ 33 , 47 , 53 ] calculated the reduction in LOS as hospital cost saving. The first study found that EMR systems were associated with 5.9% to 10.3% higher cost per discharge while with the implementation of a patient flow system, Jensen [ 33 ] reported that the hospital saved between 67,800 and 214,200 USD. The transition from traditional into digital radiology room through the implementation of a PACS system was found to reduce 90% of the film [ 41 ]. Staff satisfaction was examined in a study [ 49 ] which reported positive outcomes after the implementation of an electronic prescribing system. In a study about a workflow management system, Li et al. [ 35 ] found that the intervention greatly improved sonographers’ productivity while reducing their stress level, which was measured by a 5-point Likert scale. Measures related to organisational outcome are an interesting part of the HIS literature because most of the evidence in patient flow intervention focused primarily on patient-related outcome measures.

Impacts on process measures.

Studies examined a variety of measures related to staff productivity in clinical processes, and medical guideline adherence. Four studies examined the effect of HIS on the number of medical services performed by the staff. Two studies showed increased number of surgeries [ 31 ] and radiology tests [ 41 ]. Nitrosi and colleagues [ 41 ] studied the impacts of a PACS and found that the number of imaging procedures increased by 7% although the number of technologies and radiologists remained unchanged. An increase of 37% in the number of surgeries after a surgery information system was observed by Gomes and Lapao [ 31 ]. However, EHR implementation was found to decrease the number of patients that clinical staff could see [ 55 ] although the negative impact was only temporary and resolved three months post-implementation. The implementation of HIS did not change the medical guideline adherence of the staff when they are already providing care that adheres to the relevant guideline [ 60 ]. The number of patients seen per shift by medical staff was measured by Mohan, Bishop, and Mallows [ 56 ] in an investigation of the effectiveness of an EMR system and the impact was negative. Mathews et al. [ 37 ] and Tran et al. [ 49 ] both measured the impact of HIS on the percentage of early discharged patients and show positive outcomes. Finally, Tran et al. [ 49 ] reported an increase in the number of prescriptions prepared the day before discharge as a positive effect of a prescription system.

Impacts on structure measures.

Evidence on the impact of HIS on structure measures was more limited than data on process and outcome measures. Six of the 44 studies reported some data on structure measures. These structure measures are related to flow problems facing healthcare organisations and they were studied in ED settings. Almost all of the six studies reported positive impacts of HIS on these structure measures including the number of patient diversions and the number of ED patients with LOS over 12h [ 33 ], the proportion of early discharged patients [ 37 ], ED avoidance percentage [ 38 ], and the number and proportion of access blocks and hospital occupancy rates [ 27 ]. The study of Crilly et al. [ 27 ] found that the number of access blocks and hospital occupancy rates did not change after the implementation of a patient admission prediction system, but this is actually a positive outcome because the hospital presentations were increasing during the study period. By contrast, in one study, Mohan, Bishop, and Mallows [ 56 ] investigated the effect of an EMR system on the percentage of ambulance offloading time of more than 30 min which is also known as ambulance boarding and they found that the percentage went up from 10.5% to 13.3%.

5.3 Quality assessment of the included studies

Using the GRADE approach to assess the quality level of the evidence through their study design, two RCT studies [ 32 , 60 ] were assessed as high quality and 38 observational studies using retrospective or prospective data were rated low quality. Four studies including three expert opinions and one stating improvement without figures did not provide objective evidence and they were rated ‘0’ (the lowest rating). Two studies using multi-method design with both qualitative and quantitative components were rated low quality, based on the assessment of their quantitative component. Details of the quality assessment are provided in S5 File , Quality assessment of the included studies.

6. Discussion

6.1 summary of key findings.

This systematic review summarised and synthesised evidence from studies about HISs that have been applied to improve patient flow in both inpatient and outpatient settings. Overall, 33 out of the 44 included studies reported positive impacts of HIS on patient flow measures while 7 determined negative impacts, and 4 studies reported no significant impact. Half of the studies focused on patient flow at the departmental level; however, 18 studies reported the impact of HIS on the hospital-wide level and 4 studies reported network-wide impacts on HIS. Healthcare settings adopted at least 17 types of HIS to address patient flow problems and improve care efficiency.

We found that core features of the HIS interventions, that affected patient flow, included patient tracking, documentation management, order entry, patient registration, bed management, decision support, discharge management, prescription management and patient flow reporting. When it comes to the impacts of HIS on specific patient flow measures, most studies focused on outcome measures at both: patient (individual) and organisational level. Changes in individual outcomes were evident in time-related measures including length of stay (LOS), waiting time, treatment time, test turnaround time (TAT), and boarding time, and other measures such as left without being seen and patient satisfaction. Organisational outcome measures were noted in hospital costs, film saving, staff satisfaction, and staff stress level. Process measures and structure measures, although less examined in the included studies than outcome measures, are important measures. While process measures related to staff productivity and guideline adherence, structure measures included flow problems such as patient diversion, access block, hospital occupancy, ambulance offloading time, and ED patient with LOS over 12 h.

Noted HIS benefits included improvements in various patient flow aspects: access to needed information, staff communication, care coordination, work processes, and decision support. Ineffective interaction between hospital units is one of the most common causes of poor patient flow [ 64 ]. HISs were effective in fostering care coordination and collaboration among multidisciplinary teams by imposing a common set of flow key performance indicators (KPIs), and metrics into practice. The application of these common, sometimes “simple”, rules help develop common understandings and it is a key to governing complex systems [ 12 ]. In addition, the involvement of all team members in the development process of HIS is critical to achieving shared understandings. In this review, the effectiveness of HIS in care coordination was evident in many care processes such as patient check-in [ 59 ], elective waiting list management [ 31 ], bed management [ 36 , 48 ], ambulance distribution [ 38 ], and discharge [ 36 , 37 , 49 ]. By integrating information from multiple siloed systems, patient flow-related HIS reduce the time needed for care providers to acquire sufficient information to make critical decisions. Real-time data, notifications, and alerts functions are key features that enabled users to get the most updated information in a timely manner. The development of HISs often included redesigning the embedded care process or processes, an opportunity for care settings to eliminate redundant steps and apply best practices to their care processes. Streamlined work processes helped reduce waiting time for test results and free up staff from redundant information [ 22 , 34 ]. In addition, high degree of automation resulting from the HIS adoption contributed to the reduction in human errors, which can cause medical and health complications, and cognitive workload for hospital staff as they were not required to remember complex rules.

However, it still remains unclear how and why these interventions produced or did not produce positive or negative impacts. Most of the included studies were observational, before and after studies, making it challenging to establish the cause and effect link between HIS interventions and changes in patient flow measures. This has important implications because without a thorough understanding of why and how HIS affected patient flow, it is difficult to generalise the findings to other healthcare settings.

6.2 Strength and limitations

To date, several systematic reviews have been conducted to investigate interventions addressing patient flow problems; however, they focused mostly on operational methods such as triage, fast track, streaming [ 2 ]. Systematic reviews on the impact of HIS on patient flow are small in number and limited to single specific systems such as CPOE [ 5 ]. To the best of our knowledge, this review was the first attempt to evaluate a broad range of HISs applied in patient flow management. The novelty of this review lies in its research aim, and inclusion criteria, unlike most previous reviews on patient flow interventions, here, we included different types of HISs and broad scope of healthcare settings including departmental, organisational and network levels. Our findings provide different stakeholders with important insights for their implementation and adoption of HISs to optimise patient flow.

However, this review has several limitations. The first relates to the heterogeneous nature of the search terminology and the quantity and scope of the evidence. Although we conducted a comprehensive search, in many important domains, we could only identify a limited number of studies. The second limitation relates to the synthesis of varied outcomes and a broad range of HISs. In this review, we attempted to address this limitation by adopting analytic frameworks, which were based on domain experts and published literature, and by synthesising not only the health information system but also their functional features. Third, descriptions of the HIS interventions and the implementation process were often very limited, making it challenging to fully assess the system features and associated benefits. Fourth, most of the included studies are before-and-after, observational studies and therefore understanding of how and why HISs affected patient flow outcomes was very limited. Finally, we decided not to include a meta-analysis because of the diverse, heterogeneous outcomes reported in the included studies. A meta-analysis, in this case, is inappropriate and can be more of a hindrance than a help [ 65 ].

6.3 Implications for patient flow management practice

Hospitals and care centres have implemented several interventions to tackle patient flow problems to deliver optimal care. However, up until recently, most of the efforts were focused on addressing ED overcrowding problems [ 3 , 66 , 67 ]. It is evident in the literature that focusing solely on ED problems will not likely achieve optimal flow because EDs do not operate separately, rather they are part of an interconnected system [ 68 ]. Therefore, literature has urged that patient flow needs to be viewed from the whole system of care viewpoint and called for a shift from ED-focused to system-wide or hospital-wide interventions [ 12 , 69 ]. However, the gap between understanding the problem and having solutions to solve the problem seems still far. For example, even a holistic approach like Lean healthcare was still attached to a specific department or care process [ 4 ]. The frequently reported intervention to improve inpatient flow was implementing a specialised staff or team to coordinate patient flow across hospital units; however, the solution still posed significant challenges [ 3 ]. This systematic review found that apart from 22 studies focusing on department level, many studies reported hospital-wide or even network-wide level. HISs’ potential to address patient flow at the hospital-wide level were noted in their ability to improve communication between multidisciplinary teams [ 25 , 36 ], enhance care coordination [ 36 , 49 ], improve access to needed information [ 41 , 43 ], and streamline care processes [ 25 , 59 ]. One of the prominent causes of admission bottleneck is inefficient discharges [ 68 ] because any delays in inpatient discharge will increase hospital occupancy and ED overcrowding [ 69 ]. HISs showed their effectiveness in discharge prediction and established standardised discharge criteria for improving the discharge process [ 37 ]. These “medical-readiness criteria” have been shown to facilitate efficient planning and care coordination [ 37 ]. Addressing patient flow problems sometimes goes beyond hospital scope to a higher level of network-wide scope. A dashboard system was developed in Alberta, Canada to address ED overcrowding by coordinating emergency services between different emergency rooms within the region [ 9 ]. HISs were also used within a network of different hospitals to address the need for rehabilitation care services and improve the consultation process [ 42 ]. HISs can be scalable to a nationwide level to reduce waiting time for elective surgical patients [ 31 ]. By providing information about capacity, occupancy and demand, they can be highly effective in addressing the mismatch between supply and demand to improve patient flow.

6.4 Implications for future research

Moving forward, this review suggests important areas for future research in the field. First, additional studies need to explore barriers and facilitators of the HISs related to patient flow management. This will offer valuable implications for healthcare organisations to drive their HIS project to success and derive the most from their investment. Second, learning about the effectiveness of HISs on patient flow and associated factor during the post-implementation phase could help to advance the field. This is because of the evolutionary nature of HIS development in which factors associated with the application of HIS can be captured and used as lessons learned for the next evolution of the HIS [ 70 ]. In this review, only the study of Inokuchi et al. [ 32 ] addressed this topic. Patient flow is often negatively affected during the implementation of HIS because of changes in the workflow and human resources. Although the effect seemed temporary, learning about these periods and associated factors will bring implications for researchers and policymakers when considering the project timeline and expected challenges. Furthermore, although HISs are found to help healthcare organisations address patient flow management areas such as care coordination, timely access to information, and communication barriers, understanding why and how HIS could enhance each of these aspects can be extremely helpful. Part of the reasons to explain this is because most of the selected studies in this review did not include adequate details of the underlining technologies of the HIS interventions such as: what are the technical supports and architectures, what are the input and output data, or how the output data are represented in the user interface. The lack of technical specifications of the HIS interventions made it hard to fully comprehend how they contributed to the changes in patient flow management. Finally, during the last two years, the COVID-19 pandemic has completely disrupted patient flow management all over the world. Yet, we could not identify any studies on the role of HIS in remedying the impacts of the pandemic on patient flow.

7. Conclusion

Health information systems (HISs) provide clear benefits in managing patient flow over traditional paper record management systems. However, without a systematic evaluation and summary of the available evidence, stakeholders interested in adopting HISs in healthcare settings for patient low management might be lost in the ocean of information. This is especially true when it comes to the questions of what HIS to invest, what benefits and impacts to expect and how to maximize the values from their investment. This systematic review has revealed an increasing interest in adopting HIS to address patient flow issues in healthcare settings in the last decade. HISs can be effective solutions for patient flow management at the organisational-wide or even network-wide levels due to their great scalability and integrability. HISs were often found to be effective in improving communication and care coordination between team members, providing timely access to high quality information for decision making, and streamlining care processes. These improvements contributed to more efficient patient flow throughout the care continuum. As more healthcare and health-related data are generated, there are great opportunities for HISs such as decision support systems, and dashboard systems to help healthcare organisations harness the power of big-data analytics and achieve optimal patient flow. This review shows that HISs can impact various aspects of patient flow at different levels of care; however, how and why they delivered the impacts will require further research.

Supporting information

S1 file. search strategy..

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0274493.s001

S2 File. Reported benefits of HISs on patient flow management.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0274493.s002

S3 File. Table of all included studies and findings.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0274493.s003

S4 File. Example of data extraction form.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0274493.s004

S5 File. Quality assessment of the included studies.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0274493.s005

S6 File. PRISMA checklist.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0274493.s006

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the Faculty of Information Technology (Monash University) subject librarian, Mario Sos for his great expertise and valuable feedback in developing the search strategy. We are grateful for generous help from Quang H Vo in screening the titles, abstracts and full-text papers in our review. Also, Angela Melder from Monash Centre for Health Research and Implementation, Monash University and Monash Health gave us valuable feedback on the inclusion/exclusion criteria during the screening process.

- View Article

- PubMed/NCBI

- Google Scholar

- 12. Rutherford PA, Provost LP, Kotagal UR, Luther K, Anderson A. Achieving hospital-wide patient flow. IHI White Paper. Cambridge: Institute for Healthcare Improvement. 2017.

- 17. Covidence systematic review software, Veritas Health Innovation, Melbourne, Australia. Available at www.covidence.org .

To read this content please select one of the options below:

Please note you do not have access to teaching notes, methods for evaluating hospital information systems: a literature review.

EuroMed Journal of Business

ISSN : 1450-2194

Article publication date: 16 May 2008

It is widely accepted that the use of information and communication technology (ICT) in the healthcare sector offers great potential for improving the quality of services provided, the efficiency and effectiveness of personnel, and also reducing organizational expenses. This paper seeks to examine various hospital information system (HIS) evaluation methods.

Design/methodology/approach

In this paper a comprehensive search of the literature concerning the evaluation of complex health information systems is conducted and used to generate a synthesis of the literature around evaluation efforts in this field. Three approaches for evaluating hospital information systems are presented – user satisfaction, usage, and economic evaluation.

The main results are that during the past decade, computers and information systems, as well as their resultant products, have pervaded hospitals worldwide. Unfortunately, methodologies to measure the various impacts of these systems have not evolved at the same pace. To summarize, measurement of users' satisfaction with information systems may be the most effective evaluation method in comparison with the rest of the methods presented.

Practical implications

The methodologies, taxonomies and concepts presented in this paper could benefit researchers and practitioners in the evaluation of HISs.

Originality/value

This review points out the need for more thorough evaluations of HISs that look at a wide range of factors that can affect the relative success or failure of these systems.

- Information systems

- Customer satisfaction

- Economic performance

Aggelidis, V.P. and Chatzoglou, P.D. (2008), "Methods for evaluating hospital information systems: a literature review", EuroMed Journal of Business , Vol. 3 No. 1, pp. 99-118. https://doi.org/10.1108/14502190810873849

Emerald Group Publishing Limited

Copyright © 2008, Emerald Group Publishing Limited

Related articles

We’re listening — tell us what you think, something didn’t work….

Report bugs here

All feedback is valuable

Please share your general feedback

Join us on our journey

Platform update page.

Visit emeraldpublishing.com/platformupdate to discover the latest news and updates

Questions & More Information

Answers to the most commonly asked questions here

- Research article

- Open access

- Published: 04 September 2014

Implementing electronic health records in hospitals: a systematic literature review

- Albert Boonstra 1 ,

- Arie Versluis 2 &

- Janita F J Vos 1

BMC Health Services Research volume 14 , Article number: 370 ( 2014 ) Cite this article

94k Accesses

169 Citations

55 Altmetric

Metrics details

The literature on implementing Electronic Health Records (EHR) in hospitals is very diverse. The objective of this study is to create an overview of the existing literature on EHR implementation in hospitals and to identify generally applicable findings and lessons for implementers.

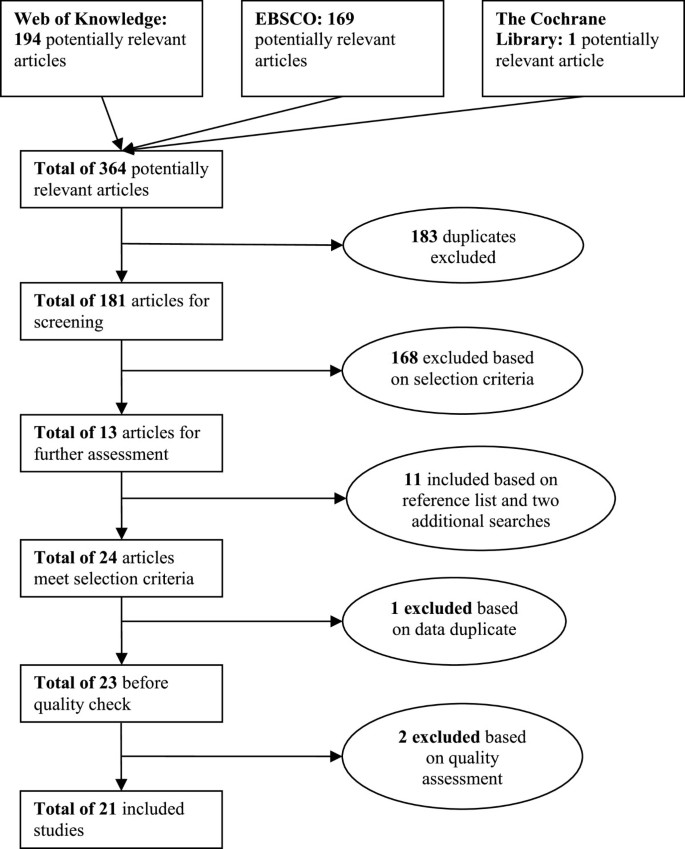

A systematic literature review of empirical research on EHR implementation was conducted. Databases used included Web of Knowledge, EBSCO, and Cochrane Library. Relevant references in the selected articles were also analyzed. Search terms included Electronic Health Record (and synonyms), implementation, and hospital (and synonyms). Articles had to meet the following requirements: (1) written in English, (2) full text available online, (3) based on primary empirical data, (4) focused on hospital-wide EHR implementation, and (5) satisfying established quality criteria.

Of the 364 initially identified articles, this study analyzes the 21 articles that met the requirements. From these articles, 19 interventions were identified that are generally applicable and these were placed in a framework consisting of the following three interacting dimensions: (1) EHR context, (2) EHR content, and (3) EHR implementation process.

Conclusions

Although EHR systems are anticipated as having positive effects on the performance of hospitals, their implementation is a complex undertaking. This systematic review reveals reasons for this complexity and presents a framework of 19 interventions that can help overcome typical problems in EHR implementation. This framework can function as a reference for implementers in developing effective EHR implementation strategies for hospitals.

Peer Review reports

In recent years, Electronic Health Records (EHRs) have been implemented by an ever increasing number of hospitals around the world. There have, for example, been initiatives, often driven by government regulations or financial stimulations, in the USA [ 1 ], the United Kingdom [ 2 ] and Denmark [ 3 ]. EHR implementation initiatives tend to be driven by the promise of enhanced integration and availability of patient data [ 4 ], by the need to improve efficiency and cost-effectiveness [ 5 ], by a changing doctor-patient relationship toward one where care is shared by a team of health care professionals [ 5 ], and/or by the need to deal with a more complex and rapidly changing environment [ 6 ].

EHR systems have various forms, and the term can relate to a broad range of electronic information systems used in health care. EHR systems can be used in individual organizations, as interoperating systems in affiliated health care units, on a regional level, or nationwide [ 1 , 2 ]. Health care units that use EHRs include hospitals, pharmacies, general practitioner surgeries, and other health care providers [ 7 ].

The implementation of hospital-wide EHR systems is a complex matter involving a range of organizational and technical factors including human skills, organizational structure, culture, technical infrastructure, financial resources, and coordination [ 8 , 9 ]. As Grimson et al. [ 5 ] argue, implementing information systems (IS) in hospitals is more challenging than elsewhere because of the complexity of medical data, data entry problems, security and confidentiality concerns, and a general lack of awareness of the benefits of Information Technology (IT). Boonstra and Govers [ 10 ] provide three reasons why hospitals differ from many other industries, and these differences might also affect EHR implementations. The first reason is that hospitals have multiple objectives, such as curing and caring for patients, and educating new physicians and nurses. Second, hospitals have complicated and highly varied structures and processes. Third, hospitals have a varied workforce including medical professionals who possess high levels of expertise, power, and autonomy. These distinct characteristics justify a study that focuses on the identification and analysis of the findings of previous studies on EHR implementation in hospitals.

Study aim, theoretical framework, and terminology

In dealing with the complexity of EHR implementation in hospitals, it is helpful to know which factors are seen as important in the literature and to capture the existing knowledge on EHR implementation in hospitals. As such, the objective of this research is to identify, categorize, and analyze the existing findings in the literature on EHR implementation processes in hospitals. This could contribute to greater insight into the underlying patterns and complex relationships involved in EHR implementation and could identify ways to tackle EHR implementation problems. In other words, this study focusses on the identification of factors that determine the progress of EHR implementation in hospitals. The motives behind implementing EHRs in hospitals and the effects on performance of implemented EHR systems are beyond the scope of this paper.

To our knowledge, there have been no systematic reviews of the literature concerning EHR implementation in hospitals and this article therefore fills that gap. Two interesting related review studies on EHR implementation are Keshavjee et al. [ 11 ] and McGinn et al. [ 12 ]. The study of Keshavjee et al. [ 11 ] develops a literature based integrative framework for EHR implementation. McGinn et al. [ 12 ] adopt an exclusive user perspective on EHR and their study is limited to Canada and countries with comparable socio-economic levels. Both studies are not explicitly focused on hospitals and include other contexts such as small clinics and national or regional EHR initiatives.

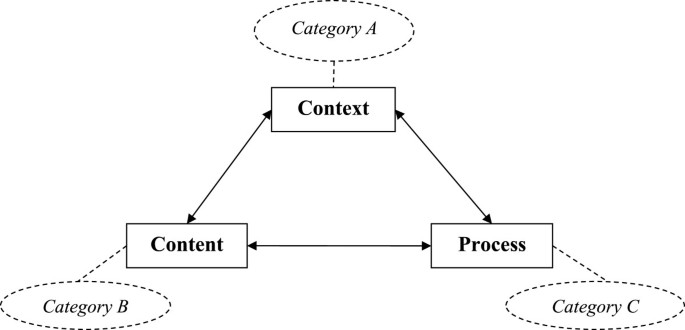

This systematic review is explicitly focused on hospital-wide, single hospital EHR implementations and identifies empirical studies (that include collected primary data) that reflect this situation. The categorization of the findings from the selected articles draws on Pettigrew’s framework for understanding strategic change [ 13 ]. This model has been widely applied in case study research into organizational contexts [ 14 ], as well as in studies on the implementation of health care innovations [ 15 ]. It generates insights by analyzing three interactive dimensions – context , content , and process – that together shape organizational change. Pettigrew’s framework [ 13 ] is seen as applicable because implementing an EHR artefact is an organization-wide effort. This framework was specifically selected for its focus on organizational change, its ease of understanding, and its relatively general dimensions allowing a broad range of findings to be included. The framework structures and focusses the analysis of the findings from the selected articles.

An organization’s context can be divided into internal and external components. External context refers to the social, economic, political, and competitive environments in which an organization operates. The internal context refers to the structure, culture, resources, capabilities, and politics of an organization. The content covers the specific areas of the transformation under examination. In an EHR implementation, these are the EHR system itself (both hardware and software), the work processes, and everything related to these (e.g. social conditions). The process dimension concerns the processes of change, made up of the plans, actions, reactions, and interactions of the stakeholders, rather than work processes in general. It is important to note that Pettigrew [ 13 ] does not see strategic change as a rational analytical process but rather as an iterative, continuous, multilevel process. This highlights that the outcome of an organizational change will be determined by the context, content, and process of that change. The framework with its three categories, shown in Figure 1 , illustrates the conceptual model used to categorize the findings of this systematic literature review.

Pettigrew ’ s framework [ 13 ] ] and the corresponding categories.

In the literature, several terms are used to refer to electronic medical information systems. In this article, the term Electronic Health Record (EHR) is used throughout. Commonly used terms identified by ISO (the International Organization for Standardization) [ 16 ] plus another not identified by ISO are outlined below and used in our search. ISO considers Electronic Health Record (EHR) to be an overall term for “ a repository of information regarding the health status of a subject of care , in computer processable form ” [ 16 ], p. 13. ISO uses different terms to describe various types of EHRs. These include Electronic Medical Record (EMR), which is similar to an EHR but restricted to the medical domain. The terms Electronic Patient Record (EPR) and Computerized Patient Record (CPR) are also identified. Häyrinen et al. [ 17 ] view both terms as having the same meaning and referring to a system that contains clinical information from a particular hospital. Another term seen is Electronic Healthcare Record (EHCR) which refers to a system that contains all the available health information on a patient [ 17 ] and can thus be seen as synonymous with EHR [ 16 ]. A term often found in the literature is Computerized Physician Order Entry (CPOE). Although this term is not mentioned by ISO [ 16 ] or by Häyrinen et al. [ 17 ], we included CPOE for three reasons. First, it is considered by many to be a key hospital-wide function of an EHR system e.g. [ 8 , 18 ]. Second, from a preliminary analysis of our initial results, we found that, from the perspective of the implementation process, comparable issues and factors emerged from both CPOEs and EHRs. Third, the implementation of a comprehensive electronic medical record requires physicians to make direct order entries [ 19 ]. Kaushal et al. define a CPOE as “ a variety of computer - based systems that share the common features of automating the medication ordering process and that ensure standardized , legible , and complete orders ” [ 18 ], p. 1410. Other terms found in the literature were not included in this review as they were considered either irrelevant or too broadly defined. Examples of such terms are Electronic Client Record (ECR), Personal Health Record (PHR), Digital Medical Record (DMR), Health Information Technology (HIT), and Clinical Information System (CIS).

Search strategies

In order for a systematic literature review to be comprehensive, it is essential that all terms relevant to the aim of the research are covered in the search. Further, we need to include relevant synonyms and related terms, both for electronic medical information systems and for hospitals. By adding an * to the end of a term, the search engines pick out other forms, and by adding “ “ around words one ensures that only the complete term is searched for. Further, by including a ? as a wildcard character, every possible combination is included in the search.

The search used three categories of keywords. The first category included the following terms as approximate synonyms for hospital: “hospital*”, “healthcare”, and “clinic*”. The second category concerned implementation and included the term “implement*”. For the third category, electronic medical information systems, the following search terms were used: “Electronic Health Record*”, “Electronic Patient Record*”, “Electronic Medical Record*”, “Computeri?ed Patient Record*”, “Electronic Healthcare Record*”, “Computeri?ed Physician Order Entry”.

This relatively large set of keywords was necessary to ensure that articles were not missed in the search, and required a large number of search strategies to cover all those keywords. As we were seeking papers about the implementation of electronic medical information systems in hospitals , the search strategies included the terms shown in Table 1 .

The following three search engines were chosen based on their relevance to the field and their accessibility by the researcher: Web of knowledge, EBSCO, and The Cochrane Library. Most search engines use several databases but not all of them were relevant for this research as they serve a wide range of fields. Appendix A provides an overview of the databases used. The reference lists included in articles that met the selection criteria were checked for other possibly relevant studies that had not been identified in the database search.

The articles identified from the various search strategies had to be academic peer-reviewed articles if they were to be included in our review. Further, they were assessed and had to satisfy the following criteria to be included: (1) written in English, (2) full text available online, (3) based on primary empirical data, (4) focused on hospital-wide EHR implementation, and (5) meeting established quality criteria. A long list of abstracts was generated, and all of them were independently reviewed by two of the authors. They independently reviewed the abstracts, eliminated duplicates and shortlisted abstracts for detailed review. When opinions differed, a final decision over inclusion was made following a discussion between the researchers.

Data analysis

The quality of the articles that survived this filtering was assessed by the first two authors using the Standard Quality Assessment Criteria for Evaluating Primary Research Papers [ 18 ]. In other words, the quality of the articles was jointly assessed by evaluating whether specific criteria had been addressed, resulting in a rating of 2 (fully addressed), 1 (partly addressed), or 0 (not addressed) for each criteria. Different questions are posed for qualitative and quantitative research and, in the event of a mixed-method study, both questionnaires were used. Papers were included if they received at least half of the total possible points, admittedly a relatively liberal cut-off point given comments in the Standard Quality Assessment Criteria for Evaluating Primary Research Papers [ 20 ].

The next step was to extract the findings of the reviewed articles and to analyze these with the aim of reaching general findings on the implementation of EHR systems in hospitals. Categorizing these general findings can increase clarity. The earlier introduced conceptual model, based on Pettigrew’s framework for understanding strategic change, includes three categories: context (A), content (B), and process (C). As our review is specifically aimed at identifying findings related to the implementation process, possible motives for introducing such a system, as well as its effects and outcomes, are outside its scope. The authors held frequent discussions between themselves to discuss the meaning and the categorization of the general findings.

Paper selection

Applying the 18 search strategies listed in Table 1 with the various search engines resulted in 364 articles being identified. The searches were carried out on 12 March 2013 for search strategies 1–15 and on 18 April 2013 for search strategies 16–18. The latter three strategies were added following a preliminary analysis of the first set of results which highlighted several other terms and descriptions for information technology in health care. Not surprisingly, many duplicates were included in the 364 articles, both within and between search engines. Using the Refworks functions for identifying exact and close duplicates, 160 duplicates were found. However, this procedure did not identify all the duplicates present and the second author carried out a manual check that identified an additional 23 duplicates. When removing duplicates, we retained the link to the first search engine that identified the article and, as the Web of Knowledge was the first search engine used, most articles appear to have stemmed from this search engine. This left 181 different articles which were screened on title and abstract to check whether they met the selection criteria. When this was uncertain, the contents of the paper were further investigated. This screening resulted in just 13 articles that met all the selection criteria. We then performed two additional checks for completeness. First, checking the references of these articles identified another nine articles. Second, as suggested by the referees of this paper, we also used the term “introduc*” instead of “implement*”, together with the other two original categories of terms, and the term “provider” instead of “physician”, as part of CPOE. Each of these two searches identified one additional article (see Table 1 ). Of these resulting 24 articles, two proved to be almost identical so one was excluded, resulting in 23 articles for a final quality assessment.The results of the quality assessment can be found in Appendix B. The results show that two articles failed to meet the quality threshold and so 21 articles remained for in-depth analysis. Figure 2 displays the steps taken in this selection procedure.

Selection procedure.

To provide greater insight into the context and nature of the 21 remaining articles, an overview is provided in Table 2 . All the studies except one were published after 2000. This reflects the recent increase in effort to implement organization-wide information systems, such as EHR systems, and also increasing incentives from governments to make use of EHR systems in hospitals. Of the 21 studies, 14 can be classified as qualitative, 6 as quantitative, and 1 as a mixed-method study. Most studies were conducted in the USA, with eight in various European countries. Teaching and non-teaching hospitals are almost equally the subject of inquiry, and some researchers have focused on specific types of hospitals such as rural, critical access, or psychiatric hospitals. Ten of the articles were in journals with a five-year impact factor in the Journal Citation Reports 2011 database. There is a huge difference in the number of citations but one should never forget that newer studies have had fewer opportunities to be cited.

Theoretical perspectives of reviewed articles

In research, it is common to use theoretical frameworks when designing an academic study [ 41 ]. Theoretical frameworks provide a way of thinking about and looking at the subject matter and describe the underlying assumptions about the nature of the subject matter [ 42 ]. By building on existing theories, research becomes focused in aiming to enrich and extend the existing knowledge in that particular field [ 42 ]. To provide a more thorough understanding of the selected articles, their theoretical frameworks, if present, are outlined in Table 3 .

It is striking that no specific theoretical frameworks have been used in the research leading to 13 of the 21 selected articles. Most articles simply state their objective as gaining insight into certain aspects of EHR implementation (as shown in Table 1 ) and do not use a particular theoretical approach to identify and categorize findings. As such, these articles add knowledge to the field of EHR implementation but do not attempt to extend existing theories.

Aarts et al. [ 21 ] introduce the notion of the sociotechnical approach: emphasizing the importance of focusing both on the social aspects of an EHR implementation and on the technical aspects of the system. Using the concept of emergent change, they argue that an implementation process is far from linear and predictable due to the contingencies and the organizational complexity that influences the process. A sociotechnical approach and the concept of emergent change are also included in the theoretical framework of Takian et al. [ 37 ]. Aarts et al. [ 21 ] elaborate on the sociotechnical approach when stating that the fit between work processes and the information technology determines the success of the implementation. Aarts and Berg [ 22 ] introduce a model of success or failure in information system implementation. They see creating synergy among the medical work practices, the information system, and the hospital organization as necessary for implementation, and argue that this will only happen if sufficient people accept a change in work practices. Cresswell et al.’s study [ 26 ] is also influenced by sociotechnical principles and draws on Actor-Network Theory. Gastaldi et al. [ 28 ] perceive Electronic Health Records as knowledge management systems and question how such systems can be used to develop knowledge assets. Katsma et al. [ 31 ] focus on implementation success and elaborate on the notion that implementation success is determined by system quality and acceptance through participation. As such, they adopt more of a social view on implementation success rather than a sociotechnical approach. Rivard et al. [ 34 ] examine the difficulties in EHR implementation from a cultural perspective. They not only view culture as a set of assumptions shared by an entire collective (an integration perspective) but also expect subcultures to exist (a differentiation perspective), as well as individual assumptions not shared by a specific (sub-) group (fragmentation perspective). Ford et al. [ 27 ] focus on an entirely different topic and investigate the IT adoption strategies of hospitals using a framework that identifies three strategies. These are the single-vendor strategy (in which all IT is purchased from a single vendor), the best-of-breed strategy (integrating IT from multiple vendors), and the best-of-suit strategy (a hybrid approach using a focal system from one vendor as the basis plus other applications from other vendors).

To summarize, the articles by Aarts et al. [ 21 ], Aarts and Berg [ 22 ], Cresswell et al. [ 26 ], and Takian et al. [ 37 ] apply a sociotechnical framework to focus their research. Gastaldi et al. [ 28 ] see EHRs as a means to renew organizational capabilities. Katsma et al. [ 31 ] use a social framework by focusing on the relevance of an IT system as perceived by the user and the participation of users in the implementation process. Rivard et al. [ 34 ] analyze how organizational cultures can be receptive to EHR implementation. Ford et al. [ 27 ] look at adoption strategies, leading them to focus on the selection procedure for Electronic Health Records. The 13 other studies did not use an explicit theoretical lens in their research.

Implementation-related findings

The process of categorization started by assessing whether a specific finding from a study should be placed in Category A, B, or C. Thirty findings were placed in Category A (context), 31 in Category B (content), and 66 in Category C (process). Comparing and combining the specific findings resulted in several general findings within each category. The general findings are each given a code (category character plus number) and the related code is indicated alongside each specific finding in Appendix C. Findings that were only seen in one article, and thus were lacking support, were discarded.

Category A - context

The context category of an EHR implementation process includes both internal variables (such as resources, capabilities, culture, and politics) and external variables (such as economic, political, and social variables). Six general findings were identified, all but one related to internal variables. An overview of the findings and corresponding articles can be found in Table 4 . The lack of general findings related to external variables reflects our decision to exclude the underlying reasons (e.g. political or social pressures) for implementing an EHR system from this review. Similarly, internal findings related to aspects such as perceived financial benefits or improved quality of care, are outside our scope.

A1: Large (or system-affiliated), urban, not-for-profit, and teaching hospitals are more likely to have implemented an EHR system due to having greater financial capabilities, a greater change readiness, and less focus on profit

The research reviewed shows that larger or system-affiliated hospitals are more likely to have implemented an EHR system, and that this can be explained by their easier access to the large financial resources required. Larger hospitals have more financial resources than smaller hospitals [ 30 ] and system-affiliated hospitals can share costs [ 27 ]. Hospitals situated in urban areas more often have an EHR system than rural hospitals, which is attributed to less knowledge of EHR systems and less support from medical staff in rural hospitals [ 29 ]. The fact that not-for-profit hospitals more often have an EHR system fully implemented and teaching hospitals slightly more often than private hospitals is attributed to the latter’s more wait-and-see approach and the more progressive change-ready nature of public and teaching hospitals [ 27 , 32 ].

A2: EHR implementation requires the selection of a mature vendor who is committed to providing a system that fits the hospital’s specific needs

Although this finding is not a great surprise, it is relevant to discuss it further. A hospital selecting its own vendor can ensure that the system will match the specific needs of that hospital [ 32 ]. Further, it is important to deal with a vendor that has proven itself on the EHR market with mature and successful products. The vendor must also be able to identify hospital workflows and adapt its product accordingly, and be committed to a long-term trusting relationship with the hospital [ 33 ]. With this in mind, the initial price of the system should not be the overriding consideration: the organization should be willing to avoid purely cost-oriented vendors [ 28 ], as costs soon mount if problems arise.

A3: The presence of hospital staff with previous experience of health information technology increases the likelihood of EHR implementation as less uncertainty is experienced by the end-users

In order to be able to work with an EHR system, users must be capable of using information technology such as computers and have adequate typing skills [ 19 , 32 ]. Knowledge of, and previous experience with, EHR systems or other medical information systems reduces uncertainty and disturbance for users, and this results in a more positive attitude towards the system [ 29 , 32 , 37 , 38 ].

A4: An organizational culture that supports collaboration and teamwork fosters EHR implementation success because trust between employees is higher

The influence of organizational culture on the success of organizational change is addressed in almost all the popular approaches to change management, as well as in several of the articles in this literature review. Ash et al. [ 23 , 24 ] and Scott et al. [ 35 ] highlight that a strong culture with a history of collaboration, teamwork, and trust between different stakeholder groups minimizes resistance to change. Boyer et al. [ 25 ] suggest creating a favorable culture that is more adaptive to EHR implementation. However, creating a favorable culture is not necessarily easy: a comprehensive approach including incentives, resource allocation, and a responsible team was used in the example of Boyer et al. [ 25 ].

A5: EHR implementation is most likely in an organization with little bureaucracy and considerable flexibility as changes can be rapidly made

A highly bureaucratic organizational structure hampers change: it slows the process and often leads to inter-departmental conflict [ 19 ]. Specifically, appointing a multidisciplinary team to deal with EHR-related issues can prevent conflict and stimulate collaboration [ 25 ].

A6: EHR system implementation is difficult because cure and care activities must be ensured at all times

During the process of implementing an EHR system, it is of the utmost importance that all relevant information is always available [ 28 , 34 , 39 ]. Ensuring the continuity of quality care while implementing an EHR system is difficult and is an important distinction from many other IT implementations.

Category B - content

The content of the EHR implementation process consists of the EHR system and the corresponding objectives, assumptions, and complementary services. Table 5 lists the five extracted general findings. These focus on both the hardware and software of the EHR system, and its relation to work practices and privacy.

B1: Creating a fit by adapting both the technology and work practices is a key factor in the implementation of EHR

This finding elaborates on the sociotechnical approach identified in the earlier section on the theories adopted in the articles. Several authors [ 21 , 26 , 31 , 37 ] make clear that creating a fit between the EHR system and the existing work practices requires an initial acknowledgement that an EHR implementation is not just a technical project and that existing work practices will change due to the new system. By customizing and adapting the system to meet specific needs, users will become more open to using it [ 19 , 26 , 28 ].

B2: Hardware availability and system reliability, in terms of speed, availability, and a lack of failures, are necessary to ensure EHR use

In several articles, authors highlight the importance of having sufficient hardware. A system can only be used if it is available to the users, and a system will only be used if it works without problems. Ash et al. [ 24 ], Scott et al. [ 35 ], and Weir et al. [ 19 ] refer to the speed of the system as well as to the availability of a sufficient number of adequate terminals see also [ 40 ] in various locations. Systems must be logically structured [ 29 ], reliable [ 32 ], and provide safe information access [ 37 ]. Boyer et al. [ 25 ] also mention the importance of technical aspects but add that these are not sufficient for EHR implementation.