100+ Best Sociology Research Topics

Table of contents

- 1 What is Sociology Research Paper?

- 2 Tips on How To Choose a Good Sociology Research Topic

- 3 Culture and Society Sociology Research Topics

- 4 Urban Sociology Topics

- 5 Education Sociology Research Topics

- 6 Race and Ethnicity Sociology Research Topics

- 7 Medicine and Mental Health Sociology Research Topics

- 8 Family Sociology Research Topics

- 9 Environmental Sociology Research Topics

- 10 Crime Sociology Research Topics

- 11 Sociology Research Topics for High School Students

- 12.1 Conclusion

As the name suggests, Sociology is one topic that provides users with information about social relations. Sociology cuts into different areas, including family and social networks.

As the name suggests, Sociology is one topic that provides users with information about social relations. Sociology cuts into different areas, including family and social networks. It cuts across all other categories of relationships that involve more than one communicating human. Hence this is to say that sociology, as a discipline and research interest, studies the behaviour and nature of humans when associating with each other.

Sociology generally involves research. It analyses empirical data to conclude humans psychology. Factor analysis is one of the popular tools with which sociology research is carried out. Other tools that stand out are research papers.

Sociology research topics and research are deep data-based studies. With which experts learn more about the human-to-human association and their respective psychology. There are dedicated easy sociology research topics on gender and sociology research topics for college students. They are majorly passed on as a thesis. This article will consider Sociology Research papers and different types of essay topics relevant to modern times.

What is Sociology Research Paper?

A sociology Research paper or essay is written in a format similar to a report. It is fundamentally rooted in statistical analysis, Interviews, questionnaires, text analysis, and many more metrics. It is a sociology research paper because it includes studying the human state in terms of living, activity, couples and family association, and survival.

The most demanding part of a sociology research writing project is drafting a quantitative analysis. Many college projects and post-graduate theses will require quantitative analysis for results. However, sociology topics for traditional purposes may only need textual analysis founded on simple close-end questionnaires.

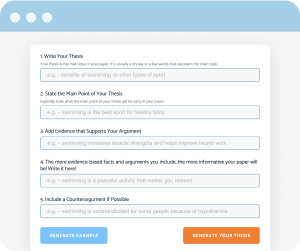

To write a sociology research topic, one will need to know the problem and how to get the needed solution. A sociology project must have a problem, a hypothesis, and the possible best solution for solving it. It must also be unique, which means it is not just a piece of writing that can be lifted anywhere from the internet. It is best to pay for a research paper founded on sociology to know how to create an excellent context matter or use it for your project.

Tips on How To Choose a Good Sociology Research Topic

It is one thing to understand the concept of a research topic and another to know how to write a sociology paper . There are processes and things that must be followed for a research paper to come outright. It includes researching, outlining, planning, and organizing the steps.

It is important to have a systematic arrangement of your steps. This is done in other to get excellent Sociology research topic ideas. The steps to getting perfect Sociology research paper topics are outlined below.

- Choose a topic that works with your Strength While it may be tempting to pick a unique topic, you should go for one that you can easily work on. This is very important as you will be able to provide a strong case. That is when dealing with a subject you understand compared to one that you barely know how works. Unless otherwise stated, always choose a topic you understand.

- Pick a good Scope The next step you should take after selecting a topic is to narrow it to a problem or several related problems that a single hypothesis can conveniently encompass. This will help you achieve a better concentration of effort and give you a very strong ground as you know the direction of the research before you even start.

While these steps are significant, you should have a concrete understanding of sociology to craft a standard project. If that is a little complex for you, you should buy a research paper on sociology at affordable prices to get what you want. You can find several reliable service providers online.

Culture and Society Sociology Research Topics

Culture and society are the foundation of sociology research projects. Humans are divided into different cultures and are categorized into societies. There is a sense of class, status, and, sadly, race bias. Sociology paper projects usually focus on these metrics to understand why humans act the way they do and what is expected over the years.

This section will consider the best sociology research paper topics examples that you can work with.

- The effect of cultural appropriation in the long term.

- The effect of media on human attitude and behavior.

- How political differences affect friendship and family relationships.

- Important social justice issues affecting society.

- Association between political affiliation and religion.

- Adult children who care for their children while also caring for their aged parents.

- Senior citizens who are beyond retirement age and still in the workforce.

- The effect and evolution of cancel culture.

- Public distrust in political appointees and elected officials.

- The unique separation challenges that those who work from home face in their workplace.

Urban Sociology Topics

With immense progress in every sector and the continuous evolution of technology, the conventional and more conservative way of association is fading off. These days, almost every person wants to be associated with the urban lifestyle. This section considers Easy sociology research titles in urban lifestyles and what they hold for the future.

- The human relationship and social media.

- Characteristics of long-lasting childhood relationship.

- Industrial Revolution and its impact on a relationship and family structure.

- Factors that lead to divorce.

- Urban spacing and policy.

- Urban services as regards local welfare.

- Socialisation: how it has evolved over time.

- Infertility and its impact on marriage success.

- Marginalised and vulnerable groups in urban areas.

Education Sociology Research Topics

Education is social. The younger age group of any society population is the target of sociology research. Most Sociology Research Topics on Education focus on how teenagers and young adults relate with themselves, modernized equipment, and the available resources.

Here are some topics on Education Sociology Research Topic:

- The relationship between success in school and socioeconomic status.

- To what extent do low-income families rely on the school to provide food for their children?

- The outcome of classroom learning compared to homeschool pupils.

- How does peer pressure affect school children?

- To what extent do standardized admission tests determine college success?

- What is the link between k-12 success and college success?

- The role of school attendance on children’s social skills progress.

- How to promote equality among school children from economic handicap backgrounds.

- The bias prevalent in the k-12 curricula approved by the state.

- The effect of preschool on a child’s elementary school success.

Race and Ethnicity Sociology Research Topics

Race and ethnicity are major categories in sociology, and as such, there are many sociology research topics and ideas that you can select from. This section considers several race-based titles for research.

- The race-based bias that happens in the workplace.

- Pros and cons of interracial marriages.

- Areas of life where race-based discrimination is prevalent.

- Racial stereotypes have the potential to destroy people’s life.

- How does nationality determine career development?

- Assimilation and immigration.

- Voter’s behaviour towards gender and race.

- Gender and racial wage gaps.

- As an American immigrant, how do I become a validated voter?

- Underpinning ethics of nationality, ethnicity, and race.

Medicine and Mental Health Sociology Research Topics

Medical sociology research topics ideas are among the more social science project work option available to social scientists. Society has always affected the growth of medicine and mental health, and some data back this claim.

There are many medicines & mental health Sociological Topics that you can work on, and the major ones are considered in this section.

- The impact of COVID-19 on our health.

- Is milk harmful to adults, or is it another myth?

- Unhealthy and healthy methods of dealing with stress.

- Is it ethical to transplant organs?

- How do people become addicts?

- How does lack of regular sleep affect our health?

- The effect of sugar consumption on our health.

- The effects of bullying on the person’s mental health.

- The relationship between social depression or anxiety and social media presence.

- The effects of school shootings on students’ mental health, parents, staff, and faculty.

Family Sociology Research Topics

Sociology research topics on family are one of the more interesting sociology-based topics that researchers and experts consider. Here are some topics in family sociology research topics.

- How does divorce affect children?

- The impact of cross-racial adoption on society and children.

- The impact of single parenting on children.

- Social programs are designed for children who have challenges communicating with their parents.

- Sociology of marriage and families.

- How to quit helicopter parenting.

- The expectation of parents on the work that nannies do.

- Should children learn gender studies from childhood?

- Can a healthy kid be raised in an unconventional family?

- How much should parents influence their children’s attitudes, behaviour, and decisions?

Environmental Sociology Research Topics

This section considers sociology research titles on the environment

- Should green energy be used instead of atomic energy sources?

- The relationship between nature and consumerism culture.

- The bias from the media during environmental issues coverage.

- Political global changes are resulting in environmental challenges.

- How to prevent industrial waste from remote areas of the world.

- Utilising of natural resources and the digital era.

- Why middle school students should be taught social ecology.

- What is the connection between environmental conditions and group behaviour?

- How can the condition of an environment affect its population, public health, economic livelihoods, and everyday life?

- The relationship between economic factors and environmental conditions.

Crime Sociology Research Topics

There are multiple Sociology research topics on crime that researchers can create projects on. Here are the top choices to select from.

- The crime rate changes in places where marijuana is legalised.

- How does the unemployment rate influence crime?

- The relationship between juvenile crime and the social, economic status of the family.

- Factors that determine gang membership or affiliation.

- How does upbringing affect adult anti-social behaviour?

- How does cultural background and gender affect how a person views drug abuse.

- The relationship between law violation and mental health.

- How can gun possession be made safe with stricter laws?

- The difference between homicide and murder.

- The difference between criminal and civil cases.

Sociology Research Topics for High School Students

High school students are a major part of sociology research due to the peculiarity of the population. Here are some topics in sociology research.

- The effect of social media usage in the classroom.

- The impact of online communication on one’s social skills.

- The difference between spiritualism and religion.

- Should males and females have the same rights in the workplace?

- How gender and role stereotypes are presented on TV.

- The effect of music and music education on teenagers.

- The effect of globalisation on various cultures.

- What influences the problematic attitudes of young people towards their future.

- The effect of meat consumption on our environment.

- The factors contributing to the rate of high school dropouts.

Sociology Research Topics for College Students

Several sociology research topics focus on college students, and this section will consider them.

- Immigration and assimilation.

- Big cities and racial segregation.

- Multicultural Society and dominant cultures.

- College students and social media.

- The role of nationalities and language at school.

- School adolescents and their deviant behaviour.

- Ways of resolving conflict while on campus.

- Social movements impact the awareness of bullying.

- The role models of the past decade versus the ones in recent times.

- The effect of changes in the educational field on new students.

Sociology is a fascinating field of study, and there are plenty of compelling research topics to choose from. Writing an essay on sociology can be a challenging task if you don’t know where to start. If you’re feeling overwhelmed, you can always turn to a writing essay service for help. There are many services that offer professional assistance in researching and crafting a sociology essay. From exploring popular sociological theories to looking at current events, there are countless topics to consider.

This article has considered a vast Sociology research topics list. The topics were divided into ten different categories directly impacted by the concept of sociology. These topic examples are well-drafted and are in line with the demand for recent sociological concepts. Therefore if you seek topics in sociology that you would love to work on, then the ones on this list are good options to consider.

However, you need to understand the basics of draft sociology research to get the benefits of these topics. If that is not possible given the time frame of the project, then you could opt to buy sociology research on your desired topic of interest.

Readers also enjoyed

WHY WAIT? PLACE AN ORDER RIGHT NOW!

Just fill out the form, press the button, and have no worries!

We use cookies to give you the best experience possible. By continuing we’ll assume you board with our cookie policy.

Click through the PLOS taxonomy to find articles in your field.

For more information about PLOS Subject Areas, click here .

- Medical sociology

- Medical humanities

- Get an email alert for Medical sociology

- Get the RSS feed for Medical sociology

Showing 1 - 10 of 10

View by: Cover Page List Articles

Sort by: Recent Popular

Taking a critical stance towards mixed methods research: A cross-disciplinary qualitative secondary analysis of researchers’ views

Sergi Fàbregues, Elsa Lucia Escalante-Barrios, [ ... ], Joan Miquel Verd

What are the characteristics that lead physicians to perceive an ICU stay as non-beneficial for the patient?

Jean-Pierre Quenot, Audrey Large, [ ... ], on behalf of the INSTINCT study group

The research topic landscape in the literature of social class and inequality

Liang Guo, Shikun Li, [ ... ], Lawrence King

Microblog sentiment analysis using social and topic context

Xiaomei Zou, Jing Yang, Jianpei Zhang

Ambiguity in Social Network Data for Presence, Sensitive-Attribute, Degree and Relationship Privacy Protection

Mehri Rajaei, Mostafa S. Haghjoo, Eynollah Khanjari Miyaneh

Enhanced Performance of Community Health Service Centers during Medical Reforms in Pudong New District of Shanghai, China: A Longitudinal Survey

Xiaoming Sun, Yanting Li, [ ... ], Yimin Zhang

Suicide Contagion: A Systematic Review of Definitions and Research Utility

Qijin Cheng, Hong Li, Vincent Silenzio, Eric D. Caine

Health-Related Quality of Life and Sense of Coherence among the Unemployed with Autotelic, Average, and Non-Autotelic Personalities: A Cross-Sectional Survey in Hiroshima, Japan

Kazuki Hirao, Ryuji Kobayashi

Suicide Ideation of Individuals in Online Social Networks

Naoki Masuda, Issei Kurahashi, Hiroko Onari

Visualizing Rank Deficient Models: A Row Equation Geometry of Rank Deficient Matrices and Constrained-Regression

Robert M. O’Brien

Connect with Us

- PLOS ONE on Twitter

- PLOS on Facebook

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Springer Nature - PMC COVID-19 Collection

Taking “The Promise” Seriously: Medical Sociology’s Role in Health, Illness, and Healing in a Time of Social Change

Bernice a. pescosolido.

Department of Sociology, Indiana University, 1022 E. Third Street, Bloomington, IN 47405 USA

In 1959, C.W. Mills published his now famous treatise on what sociology uniquely brings to understanding the world and the people in it. Every sociologist, of whatever ilk, has had at least a brush with the “sociological imagination,” and nearly everyone who has taken a sociology course has encountered some version of it. As Mills argued, the link between the individual and society, between personal troubles and social issues, between biography and history, or between individual crises and institutional contradictions represents the core vision of the discipline of sociology. While reminding ourselves of the “promise” may be a bit trite, its mention raises the critical question: Why do we have to continually remind ourselves of the unique contribution that we, as sociologists, bring to understanding health, illness, and healing?

Introduction: Taking Stock of the Intellectual and Societal Landscape of Medical Sociology

Perhaps, we remind ourselves because the sociological imagination is so complex – a multilayered perspective that ties together dynamics processes, social structures, and individual variation. While Mills ( 1959 , p. 4) himself argued that “ordinary men…do not possess the quality of mind essential to grasp the interplay,” this seems a bit overplayed. There have always been people – in the academy, in the workroom, or in the home – who have heard and understood the deafening voice of oppressive social norms drowning out opportunity. There have always been people who have noted, described, and taken advantage of changes in opportunity structures to improve their fate. And, despite modern medicine’s reductionist and mechanical view of the body, which may or may not be changing, there have always been the Rudolph Virchows, the Milton and Ruth Roemers, the George Readers, and the Howard Waitzkins, alongside the majority. While the sociological perspective may find a particular challenge in the United States with its strong strain of individualism, there have always been those who have captured the hearts, sparked the intelligence, and harnessed the energy of the group as a way to overcome the existing limits of their surroundings. From the rise [and fall] of unions; to the improvement of working conditions in toxic factory work; to the formation of professional associations in medicine, nursing and their specialties; to women’s health cooperatives designed to counter the insensitivity of regular medicine, instances of confronting the status quo through affiliation and association stand as exemplars of the tacit, “on-the-ground” understanding of the sociological imagination.

I would argue, rather, that we need to be reminded of the central premises of sociology and what we bring to table precisely because we have been successful, even if quietly so. In essence, the major dilemma that we confront at present is that the “promise” is obvious, not only to ourselves, but to others. The idea that context matters has taken hold across the sociomedical sciences, the bio-medical sciences, and even the basic sciences like genetics and cognitive science (see Pescosolido 2006 for a review). Ideas of health and health care disparities (which we have called inequalities for over 100 years in sociology, and for over 50 years in the subfield of medical sociology); fundamental causes (as Link and Phelan, 1995 , so eloquently labeled sociologists’ baseline concern with power, stratification and social differentiation); and social networks as vectors of social and organizational influence (now renamed “Network Science”) stand front and center in the concerns of the National Institutes of Health and other major scientific organizations. Whether our arguments and research findings have been persistent, robust and convincing, or whether these insights coincide with the recognition by the more reductionist sciences that even their most sophisticated approaches cannot solve the problems of the body and the mind alone, is of little consequence. When the newly appointed director of the NIH, Dr. Francis Collins, who led the Human Genome Project, announces the launching of a special program to increase attention and resources to basic behavioral and social science (November 18, 2009, www.oppnet.nih.gov ) using phrases like “synergy,” “vital component,” and “complex factors that affect individuals, our communities and our environment,” the crack in the door of mainstream biomedical science becomes just a little wider, and the seat at the table becomes just a little more possible.

Sometimes, the role of sociologists is obvious in these new declarations of important directions in science and medicine; other times, they appear as “discoveries” without much, if any, attribution. But to belabor the historical debt that contemporary health and health care researchers and policymakers may owe us is a waste of both time and energy. Sociology has a history of conceptualizing social life, making that view understandable, and having its insights and even its language absorbed as “common sense” into both academic and civil life (e.g., clique, identity, self-fulfilling prophecy, social class, disparities, networks). More to the point, Mills argued that the sociological imagination is a “task” as well as a “promise.” He described that task – “to grasp history and biography and the relations between the two within society” ( 1959 , p. 6) – through the work of major sociologists of his time as “comprehensive,” “graceful,” “intricate,” “subtle,” and “ironic.” With “many-sided constructions,” a focus on meaning, and a willingness to look across social institutions like polity, the economy, and the domestic sphere (1959, p. 6), Auguste Comte and others came to define sociology’s aspiration as the “Queen of the Social Sciences,” a phrase more commonly used now by economists or political scientists to describe their discipline. Similarly, Mills ( 1959 ) sees sociology as holding “the best statements of the full promise of the social sciences as a whole” ( 1959 , p. 24), and I have argued elsewhere that taking sociology’s view of social interactions in networks represents one promising approach to integrating the health sciences (Pescosolido 2006 ).

The complexities in topic, theory and methods, sometimes the object of divisions in sociology and sometimes a detriment in the “sound bite” approach to modern society, continue to be our strength, and are not always obvious to others who adopt the mantra of “context.” Our research focuses on how individuals, organizations, and nations are “selected and formed, liberated and repressed, made sensitive and blunted” (Mills 1959 , p. 7). We accept the unexpected, we expect latent functions of policies and actions of even those who are trying to do good, we understand that being an outsider has its advantages in understanding the world, and we embrace the notion of comparison and reject a “provincial narrowing to the interest to the Western societies” ( 1959 , p. 12). Whenever we look at a life, a “disease,” a health care system, or a nation’s epidemiological profile, examining which “values are cherished yet threatened” ( 1959 , p. 11) is inevitable. As Hung ( 2004 ) has recently documented for the SARS virus and Epstein ( 1996 ) for HIV/AIDS, the societal reactions to viral pandemics are deeply rooted in social cleavages rather than biological fact, whether this reaction unearthed the racist view of the “Yellow peril” or the homophobic view of the “Gay plague.”

In sum, at this point in time, it may be more important than ever to recall our mission and accept the uneasiness which is endemic (and according to Mills, necessary) to it. The sociological imagination requires “the capacity to shift from one perspective to another – from the political to the psychological….to range from the most impersonal and remote transformations to the most intimate features of the human self – and to see the relations between the two” ( 1959 , p. 7). Our training emphasizes this, our theories conceptualize it, and the wide variety of our research methods reflect it. We bring this self-consciousness to the problems of health, illness, and healing, and hopefully to their solutions. Which subfield of sociology, more than the sociology of health, illness, and healing, provides a critical window into making “clear the elements of contemporary uneasiness and indifference” that Mills sees as “the social scientists’ foremost political and intellectual task” ( 1959 , p. 13)? While Mills may have been premature, or flat out wrong, in his prediction that the social sciences would overthrow the dominance of the physical and biological sciences, his view was prescient regarding the rising importance of “context” in biomedical sciences ( 1959 , p. 13) and increasing doubts about the inevitable and pristine nature of science. As those inside the “House of Medicine” itself dare to question the utility of the “gold standard” (RCT, the randomized clinical trial) versus observational studies (Concato et al. 2000 ), the validity of the placebo as a “control” (Leuchter et al. 2002 ), and the robustness of “established” genetic links (Gelernter et al. 1991 ), the radical critiques of the objectivity of science and the inevitability of linear progress in science have come from inside as well as outside (Gieryn 1983 ; Latour 1999 ). It is naïve to assume or even expect a reconstruction of the prestige hierarchy of the sciences, as Mills does to some extent. He forgets that institutional supports undergird that dominance, as any of us who have served on interdisciplinary review panels will attest. Yet, the idea that there may be occasional openings for concerns and approaches by social scientists was prophetic. This may be one of those unique times to work together to push not only our understandings forward, but to foster institutional social change. At the least, it is a time when social scientists, especially sociologists, need to have their voices heard; that is, to have a place at the table to guard against a crass, out-of-date, and generally poor appropriation of the social sciences’ basic ideas and tools. Those of us who witnessed a wider acceptance of (even called for) social science methods such as ethnography in the 1980s and 1990s in the mental health research agenda, also witnessed the dumping of the term into one sentence of a traditional research proposal without any idea of its complexity, rigor, or even utility to expand the limited insights of clinical research. Bearman ( 2008 , p. vi) downplays concerns that this kind of scientific diffusion may “distort the sociological project” because “the beauty of sociology as a discipline rests in its hybridity with respect to method and data” and new research concerns can become a potential “lever” for sociology to escape some of its own “hegemonic” foci.

The Task Ahead: Mapping the Landscape of Health, Illness, and Healing for the Next Decades

As Mills reminds us, the insights of sociology are both “a terrible lesson and a magnificent one.” Perhaps, this is more true in medical sociology than in other areas of the discipline; maybe not. Yet, the historical and contemporary landscape of health, illness, and healing challenges medical sociologists to think about both the issues/topics that have drawn and continue to draw our attention, as well as new ones on the horizon.

The Metaphor of Cartography

Recently, Sigrun Olafsdottir and I ( 2009 , 2010) drew from the “cultural turn” in sociology to reframe key theoretical and methodological issues in health care utilization research. We considered whether some individuals map a larger set of choices, examined if and how they differentiate between different sources of formal treatment, and questioned whether the way we ask those in our research about their experiences shapes the responses they give. This imagery of cultural landscapes and boundaries (Gieryn 1983 , 1999 ) seems to fit the multifaceted, complex nature of health, illness, and healing in the current era. Individuals use cultural maps to make sense of the world, affecting information availability and personal understandings, as well as signaling possible appropriate action. While Gieryn’s work focuses on professions, primarily scientists and the rhetorical strategies they use to establish, extend, and protect their societal authority, these ideas have broader relevance, not only for other professionals like physicians, but for the public. In particular, the concept of “boundary-work” becomes central as individuals, whatever their position, confront illness, define disease, and react to treatment options. The term “cultural mapping,” targeting the terrain of choices, as well as individuals’ recognition, acceptance, or rejection of them, informs us about the boundaries of their experience, and values shaping action, whether their own (as in rational choice theory) or that of others (as in labeling, social influence, and social control theories).

In essence, cultural landscapes shape individuals’ everyday decisions and actions, including those of medical sociologists. The metaphor of cultural cartography allows us not only to organize our topical research agendas but also our challenges for the next generation of medical sociology. In essence, two different maps require our attention. One is a map of topographical changes in health and health care that mark out new or continued areas of inquiry; the second maps the boundaries of discipline, the joint jurisdiction of sociology with the subfield of medical sociology, and how these two symbiotically share intellectual territory.

Contextualizing and Researching Health, Medicine, Health Care, and the Biomedical Sciences: Time of Change from the Outside

There is little doubt that the essential questions of sociology and medical sociology – more specifically, of the importance of Weber’s link between lifestyle (i.e., social psychological as well as social organization) and life chances – remain paramount and require our continued attention. Causes (epidemiology) and consequences (outcomes, health services research) continue to crudely, and increasingly inaccurately, define research agendas as we emphasize more dynamic processes which connect the two. Medical sociologists continue to more broadly conceive the landscape of epidemiology than do our sister subfields of medicine and public health. That is, with regard to issues of mortality and morbidity, the distribution and the determinants of disease must consider issues of professional power, social movements, contested meaning, and social construction (or its cousin specific to medical sociology, medicalization) as well as traditional risk and protective factors like genetics, biological markers, psychological trauma, or even individuals lifestyles (Brown 1995 ; McKinlay 1996 ). To understand utilization, adherence, health care system, and outcomes, we need to incorporate dynamic views, describe different response pathways, and confront changing boundaries of legitimacy regarding potential patients, healers, and formal structures of care (Pescosolido 1991 , 1992 ).

In addition to these classic, general prescriptions, three newer but deep-seated developments call for sociological theorizing and research. Necessarily, some of these are intertwined with our classic concerns but, nevertheless, they raise new challenges.

Human Genome Project and the Larger Push for Understanding Context

Not all that new, the first phase of the project, designed to determine the sequence of base pairs in the entire human genome, began in 1990 and continued for 13 years. Yet, as Francis Collins and others have noted, we are only beginning to understand what we have and can learn both in a positive and negative sense. Sociologists have tread into that territory lightly, now starting to work their way toward the profound implications of this massive project and the larger cultural institutions that created and continue to nurture it (e.g., Phelan 2005 ). Perhaps, the most obvious is the potential for collaborative projects on epigenetics and on gene-environment interactions (g x e) (i.e., how environmental conditions which include society not only trigger or suppress genetic predispositions but, in fact, change the genome itself; Szyf 2009 ). While complicated, this may not be the most challenging. It was a recent special issue of the American Journal of Sociology (Bearman 2008 , p. vi) that turned an obvious research question on its head: “What can we learn about social structure and social processes, and what can we learn about our accounts about social structure and social processes, by ‘thinking about genetics’?” Fleshing this out even a little raises classic sociological questions. How is the genetics agenda constructed by medicine, by insurance companies, by the public, and by science itself, to name just a few? What does this mean for the definition and behavioral implications of human health, legitimate constructions of illness by the public and the profession, shifting definitions of vulnerability, and changes in the nature and targets of prejudice and discrimination? While bioethicists and philosophers have asked and deliberated on these questions, medical sociologists bring evidence to bear on the creation, maintenance, and effects of this now dominant weltanschauung in medicine, science, and society. We have the tools to ensure that the powerful forces of society are understood, elaborated, and included in our understandings of the onset of what becomes labeled disease and disorder. We have the tools to uncover the unexpected, latent functions of this direction which, in themselves, will raise new challenges for the very institutions that placed their hopes in “the language of God” (Collins 2006 ).

The Mess that Is “Translational Science” and the Need for Sociological Clarity

Of the new “medical speak” that dominates discussions of future directions, the current ubiquitous term is “translation.” Unfortunately, while critically targeting the lack of effective transfer across stakeholder communities, this term has confounded discussions and attempts to provide solutions. Even in a quick survey of existing documents that call for “translation,” at least three meanings are evident. The first translation dilemma, which can be referred to as a dissemination problem, suggests a need for more effective ways to communicate information between scientists and “end-users.” The second translation dilemma, an implementation problem (also the efficacy–effectiveness gap), suggests a need to understand how to translate science into services that result in meaningful clinical care (National Advisory Mental Health Council 2000 ). Finally, the third translation dilemma, referred to as a problem of integration , suggests that the insights and potential contributions of different branches of science have not been fully incorporated in efforts to either establish research agendas or to provide high quality effective care in the formal treatment sector.

Each of these suggests complicated problems, all recast as problems of “translation,” for a diverse array of stakeholder communities and, to date, traditional research approaches have not offered good answers. Each calls for sociological research on a series of basic questions. First, why do providers and consumers fail to take advantage of cutting-edge science? A frequent complaint expressed by research scientists, payers, and policy makers is that cutting-edge interventions are neither adopted in day-to-day clinical work nor accepted by individuals with health problems who might benefit. Second, why do treatments that have been “proven” to work in randomized clinical trials fail to work in real world settings? A continual frustration of providers is that clinical research fails to take into account the challenges of day-to-day clinical work and does not offer a realistic understanding of the complexities and limitations of providing care. A similar frustration of consumers and advocates is that clinical research fails to take into account the complex realities of the lives of persons who fall ill, especially those with chronic and stigmatized problems. Third, why has health services research not been able to bridge the gap to allow proven clinical interventions to find application to the “real world” needs of consumers, practitioners, payers, and policy makers (Pellmar and Eisenberg 2000 )? Each of these requires an understanding of “cultures” – the culture of the public, the culture of the clinic, the culture of community, and of organizations. Sociological research holds the potential to understand how cultures are shaped; how they are enacted; how they clash or coincide with one another; and how, in the end, cultural scripts facilitate, retard, or even prohibit institutional social change. Sometimes, these discussions have the reductionist tone of lack of motivation without understanding the power of institution and resource as well as the social network structures that cripple innovation. More importantly, these challenges call for a holistic approach to research in which different levels of change, as well as the individuals in them, are conceptualized as linked and intertwined, with outcomes measured through innovative quantitative approaches and mechanisms observed through in-depth qualitative observations. In no way would such studies exclude the expertise of other scientists; indeed they call for it. However, the multilayered, multimethod and connected approach inherent in medical sociology provides an overarching organizing framework that can facilitate the integration of different interdisciplinary insights (Pescosolido 2006 ).

The “Hundred Year’s War” of American Medicine and Mechanic’s Continued Call for Sociological Understandings

Ironically, exactly 100 years ago, the Flexner Report “closed the books” on the blueprint for the primary structure and power of medicine in America. The 1910 document, crafted by middle-class men with middle-class values building the new institutions of industrial society, called for the active and specific funneling of large amounts of money from the new industrial tycoons who, themselves, had other ideas about what the US health care system should look like (Pescosolido and Martin 2004 ). However, drawing from the recent “successes” of the “new” scientific medical schools of Germany, France, and the United Kingdom, the Flexner Report set a trajectory and the Rockefeller Foundation fiscally supported a process of mimetic isomorphism for other emergent medical institutions. America’s health care system was built primarily with private funds, dominated by the allopathic physician, and supported though a fee-for-service economy (Freidson 1970 ; Starr 1982 ). The era from the Flexner report until President Nixon’s proclamation of a “Health Care Crisis” in 1970 has been described by McKinlay and Marceau ( 2002 ) as the “Golden Age of Doctoring,” by Clarke and her colleagues as the “Medicalization Era” (Clarke and Shim 2010 ), and by us, using Eliot Freidson’s ( 1970 ) terms, as “The Era of Professional Dominance” (Pescosolido and Boyer 2001 ). Working in a primarily private health care system, physicians determined both the nature of medical care and the arrangements under which it was provided. Even with the introduction of private (and later public) insurance, the American system remained an anomaly on the global landscape. The richest country in the world, which spent more on research, technology, and care than any other, also was home to the greatest number and proportion of uninsured citizens and to standard indicators of population health that fell way below those of countries with fewer resources and less of them devoted to health.

The year 2010, 100 years after the Flexner Report, saw the initial passage of President Obama’s Health Care Plan. What will result from this shift in the U.S. position on health care as right and as privilege? Will it be dramatic and devastating as some claim? Dramatic and good as others claim? Given the early capitulation to (or some would say, inclusion) of key opponents of earlier reforms, will this plan result in more patching of an essentially private system in the stranglehold of insurance and pharmaceutical companies? Will reform suffer the fate of what many of us thought/hoped would be the “second great transformation” (Stone 1999 ) or “construction of the second social contract” between American medicine and society (Pescosolido and Kronenfeld 1995 ) in the Clinton Health Reform of 1990? Or, will this “accommodation,” as was the case with high physician reimbursement levels during the Medicaid/Medicare deliberations, mean that something will actually change?

The failed federal effort of the 1990s nevertheless ushered in the “Era of Managed Care” which both supporters and critics of the existing health care system feared (Pescosolido and Boyer 2001 ). But as Mechanic et al. ( 2001 ) documented, the introduction of managed care did little to change the amount of time that physicians and patients spent together in the examining room before that event. In fact, the amount of time that physicians spent in interaction with their patients was already minimal, reflecting a typical romantization of past social institutions rather than data on its actual operation. By 1999, health care scholars talked about the “backlash” against managed care which began as early as the mid-1990s and resulted in the weakening of many of its proposed strategies to limit choice of physicians, access to specialists, and cut costs. This “managed care lite” (Mechanic 2004 ) did provide a short-term control of costs which soon gave way to escalating fiscal pressure and further increases in the number of uninsured Americans. By the end of the decade, Swartz ( 1999 ) proclaimed the “death of managed care” and Vladeck ( 1999 ) announced that managed care had had its “Fifteen Minutes of Fame,” warning that “Big Fix” political solutions oversell, inevitably producing negative overreactions.

What will medicine, the health care system, and population health look like as a result of reform? At what point, and how, will we see the landscape of the US as truly different? Carol Boyer and I (2001) agree that the 1970s began the “end of unquestioned dominance,” but are we still “drifting” as Freidson ( 1970 ) warned, or are we reconstructing the American social contract between civil society and the “medical-industrial complex” (McKinlay 1974 )? How much of our view of “change” can or cannot be backed up by real data? After all, given larger claims of the “consumer backlash” or “consumer revolution” that would change the power balance, we find little significant decrease in the public’s view of the authority or expertise of physicians (Pescosolido et al. 2001 ). If there is a decrease in the confidence in American medicine, as Schlesinger ( 2002 ) claims, how much of this disillusionment is not exclusive to modern medicine, but rather reflects a generalized reaction to social institutions, developed in the modern, industrial era, to larger changes in contemporary society (Pescosolido and Rubin 2000 ). Rubin ( 1996 ) argued that the social and economic bases of modern society were “tarnished” in the early 1970s, marking a general turning point for social institutions in the face of diminished growth that had accompanied the post World War II era. To simply look at trends in the response to medicine and health care may miss the point of our general prescription to understand social life in context.

Community, professional, and the health care systems are in a state of constant change, in big and small ways, and claims of improvement or deterioration pale in comparison to actual research that contextualizes and documents societal level change (Pescosolido et al. 2010, on contentions and data on the dissipating stigma of mental illness in U.S. society). Such claims are important because they often come to have a life of their own, shaping priorities for research and treatment. But claims are research questions subject to empirical examination with social science data. Have we taken up Mills’ task to bring the “comprehensive,” “graceful,” “intricate,” and “many sided constructions” of sociology to changes in health, illness, and healing? Mechanic ( 1993 ) has repeatedly pointed out that sociologists are not well represented, doing the research on the organization of care that can provide both the subtle and dramatic, expected and ironic, impacts on the profession, the public, and health institutions. A sociological perspective, alone or integrated with others, is critical in marking and analyzing the impact on individuals, organizations, and groups of reform.

Putting Our Own House in Order: Time of Change from the Inside

There are, of course, many more important questions. At this historical moment of structural reform and reconsideration of research agendas, these appear to loom large. If medical sociologists are to attend to these or other critical issues in health, illness, and healing, a reflection on where we stand is essential. In fact, the logic of this volume was designed around the reflections of the editors, the contributors, and those who attended some of our early planning events.

Sociologists have regularly, if only occasionally, lamented our basic and internal barriers to progress – whether Lester Ward ( 1907 ) arguing that sociologists do not know enough biology to reject it or Alvin Gouldner ( 1970 ) alerting us to a brewing crisis in “Western sociology” because of a blind reliance on “objective” data (more below). Sociology weathered these critiques, changing sometimes in small ways and other times in large ways, but most often, noting the critique, integrating it in some way and to some extent in some corner of the discipline, and moving on. Sociology has survived functionalism and its dominant status attainment theory in the 1960s and 1970s, Marxism and the 1980s dominating return to historical sociology, and postmodernism’s declaration that everything is virtually unknowable except through one’s own personal experiences (in which Anthropology did not fare so well as a discipline; Pescosolido and Rubin 2000 ). Sociology is likely to both encounter and survive many more of these critiques; perhaps ironically because of the embedded Catholicism in its theory and method. While our richness lies in the breadth and inclusion, as noted above, this is also the source of confusion regarding sociology’s “brand.”

Decoding the Discipline and the Subfield: The Three Medical Sociologies

The looseness of our boundaries of inquiry and methods of intellectual mining is not without its costs. Recently, Pace and Middendorf ( 2004 ) argued that understanding the challenges in learning the heart of a discipline’s contribution requires asking a series of questions. This “decoding of the disciplines” seems just as relevant to reflecting on the research voice we use to address our “publics” (Burawoy 2005 ), whether students, ourselves, our colleagues in other disciplines, providers, policy makers, or the general population. While this approach places disciplines at the center of discussions, Pace and Middendorf ( 2004 , p. 4) note the critical but paradoxical requirement to consider the boundaries that we cross with other disciplines. Decoding first relies on the identification of “bottlenecks,” those places or issues where the end goals are not being met. They argue that, too often, this part of the process is skipped in favor of trying solutions which, while well meaning, miss the mark.

Following these directions, two often simultaneous concerns appear to echo through decades of writings on the discipline and the subfield. Mills ( 1959 ) warned of the “lazy safety of specialization” (Mills 1959 , p. 21). Gouldner ( 1970 ), Gans ( 1989 ), Burawoy ( 2005 ), and others have asked sociologists to be more engaged with civil society, more normative and less pristinely and scientifically aloof, and more willing to engage in activities that have a more immediate impact on the world. Bringing the two concerns of relevance and specialization to the same point on the intellectual map, Collins took up the concern of whether sociology “has lost its public impact or even its impulse to public action” ( 1986 , p. 1336), pointing to the proliferation of specialties as the source of internal, disciplinary boundary disputes, including pushing to the fringes those sociologists who took a more applied approach. While our subfields have allowed us to make the increasingly large professional association and annual meetings feel smaller, more personal and relevant, building up an “espirit de corps” ( 1986 , p. 1341) that facilitates the socialization of our new colleague, Collins sees the result that we “scarcely recognize the names of eminent practitioners in specialties other than our own…having become congeries of outsiders to each other” ( 1986 , p. 1340).

Medical sociology has not been immune to these centrifugal forces, arguing to the ASA that even if not formally the case, we “own” and caretake the Journal of Health and Social Behavior; revel in the realization that it has the third highest impact factor among journals in the discipline following our two flagship journals, the American Sociological Review and the American Journal of Sociology; or boast about our section membership hovering around the thousand mark. From its earliest days, Strauss ( 1957 ) articulated the fuzzy distinction between a sociology OF medicine and a sociology IN medicine which evoked the basic-applied distinction. We reported on concerns among our colleagues in medical sociology (Pescosolido and Kronenfeld 1995 ), with Levine ( 1995 ) suggesting that such territorial disputes trickle down, in part, from the larger discipline.

Not surprisingly, the second step in decoding follows from the identification of bottlenecks. In essence, knowing the landscape is key to traversing it successfully. Because Collins ( 1986 , p. 1355), in the end, finds “a pathological tendency to miss the point of what is happening in areas other than our own,” advocates that we work in two or three specialties, sequentially or simultaneously. Because Burawoy ( 2005 ) sees two dimensions that define our work (instrumental and reflexive), he argues for the legitimacy of four “brands” of sociological work which individuals can embrace simultaneously or sequentially. In medical sociology, Levine’s plea for “creative integration” draws together the insights of “structure seekers” and “meaning seekers” (Pearlin 1992 ). In fact, using a cartological metaphor, he called for us to become more “cognizant of the theoretical and methodological ‘tributaries’ that feed into the subfield that is medical sociology” (Levine 1995 , p. 2). In 1995, we argued for the integration of the mainstream and the subfield (Pescosolido and Kronenfeld 1995 ).

The Boundary Divisions that Matter: The Three Medical Sociologies

The terrain has changed because there have been deep-seated changes in the bedrock underlying medical sociology. The sources of these tectonic shifts lie in three interconnected but altered features of institutional supports. They are: (1) The demise of medical sociology training programs; (2) The growing presence of “other” sociologists in the sociology of health, illness, and healing; and (3) The increased presence of sociologists in medicine, public health, and related fields. Each comes with its own strengths and weakness, and together, they produce major impediments in building a cumulated set of findings from and for sociology in the areas of health, illness, and healing. Two dimensions are critical – training (What do we pass on in research on health, illness, and healing?) and audience (Who do we want to talk to?).

Our House and Corner of the Map: Medical Sociology by and for Medical Sociology

Post-WWII, the NIH, and particularly the NIMH, saw the development of subfields of social science within its purview. Training programs were funded in social psychology, medical sociology, and methodology, to name only a few. The demise of these training programs at sociology departments such as Yale, Wisconsin, and Indiana Universities resulted from narrowing NIH foci away from the broad concerns with stratification, institutions, medical sociology, social psychology to disease-specific problems beginning in the 1990s. But some training programs or major training emphases have survived (Rutgers, UCSF in the School of Nursing, Brandeis, Columbia), some have arisen in their wake (Indiana, Vanderbilt; Maryland), and some have fallen away (Wisconsin, Yale, UCLA).

This does not mean that there are not major medical sociologists elsewhere training individuals, nor does it mean that individuals are not doing medical sociology-relevant dissertations or research. However, it does mean two things. First, medical sociologists trained in these programs sometimes do not have the strong connection to the mainstream of the discipline, which is an aspect of Collins’ concerns. The success of our own journals and lines of research have produced a bit of insularity, pushing forward streams of research that neither draw from nor are engaged in dialog with the mainstream discussions. Whether this reflects a narrowing of the mainstream journals (see Pescosolido et al. 2007 ) or a narrowing of medical sociologists’ interests and reference groups is immaterial. Second, it also means that the findings of medical sociology that have been built over three generations have not become part of the larger stock of knowledge of the discipline and are sometimes absent in mainstream work that would profit from its insights (see below).

The main point is that the interchange between significant, relevant contributions in medical sociology and significant, relevant contributions in the mainstream disciplines and its other subfields is not happening. This decreases the accumulation of tools in the sociological toolbox, whether practitioners of our subfield, other subfields or the mainstream of the discipline.

Our Country: Mainstream Sociology with a Focus on Health, Illness, or Healing

Mills’ link between larger opportunities and challenges and individual behaviors is no less applicable to our research enterprise than it is to the phenomena we research. The availability of funding sources affects how sociologists are able to do their work; with sociology’s broad focus on social institutions, health becomes a focus of those who are concerned with general forces (e.g., inequality, organizations, and communities) than with the social indictors of outcomes. That is, health and health care is only one of a number of life chances affected by larger contextual forces. Dramatic instances of unequal life chances cannot help but draw the interests of sociologists. The increase in interdisciplinary research teams and the relative “wealth” of the NIH (e.g., versus the NSF) has brought more sociologists into research that addresses health, illness, and healing. All of these developments are good for the discipline and the subfield, as well as for the accumulation of social science and insights for the medical sciences.

Again, however, this focused attention by sociologists on areas traditionally defined as medical sociology is not without its costs. Specifically, it leads to a “quibble,” not necessarily an unimportant one, with this brand of research. As Jane McLeod so eloquently put it in her comments on the “Author Meets the Critics” Session at ASA in 2003, such work tends to suffer from “The Fatal Attraction Syndrome.” In other words, the insights of medical sociology research are ignored and “rediscovered.” Declaring the need for a sociological subfield of “social autopsy” disregards medical sociology’s line of research on social epidemiology that pioneered sociology’s focus on how issues of class, race, and gender shape mortality and morbidity (McLeod 2004 ).

This is not misrepresentation, but missed opportunity. Classic works embraced by medical sociology were penned by sociologists who did not appear to consider themselves “medical sociologists” (e.g., Erving Goffman, Everett Hughes). Rather, in contemporary research, the lack of training in and knowledge of medical sociology as a subfield yields a weaker picture of sociology’s contributions to our understanding of the social forces that shape health, illness, and healing. It may suggest to those both inside and outside the subfield that the discipline of sociology is not at the cutting edge.

Abandoning Home and Country for Richer, More Powerful Neighborhoods: Medical Sociologists Packed and Gone to Medicine, Public Health, and Policy

Differences in employment opportunities, either restricted in sociology or open in schools of medicine and public health, and the greater distribution and impact of scientific journals and dissemination outlets in those fields, create a third community on the sociological landscape. These are sociologists who tend to be very well trained in medical sociology and who bring a prominence to sociological ideas in health, illness, and healing. What can be the problem here? In fact, there is no immediate issue, because both sociologists and medical sociologists “find” much of their work. However, not all of their research can be fully integrated into the discipline without their presence, literally and figuratively, in sociology venues. The problem is that, in their geographic positions outside the discipline, they will not likely train the next generation of medical sociologists. In addition, many of these sociologists are precisely the ones who focus on health care organization and policy, a topic about which David Mechanic finds the subfield relatively weak in addressing. With the demise of strong medical sociology training programs in the top ranked departments, the two problems mentioned above are magnified. If the majority of sociologists tackling issues of health care organization and reform are outside our training spheres, this will likely exacerbate the shortage of a new generation of medical sociologists pursuing these topics. Avoiding the “loss” of their expertise to schools of public health, medicine and management alone, without a parallel emphasis in the subfield, requires effort on both sides, with each valuing the contributions and venues of the other.

Triangulating the Community Map to Develop a Blueprint for the Next Decade of Research

Rethinking communities and landscapes.

The analysis of these different locations and communities on the map of the sociology of health, illness, and healing guided our vision for this Handbook. It was meant to suggest, in Durkheimian fashion, that the whole of our contributions is greater than the sum of its parts. The sociology of health, illness, and healing is constituted and enriched by medical sociology, mainstream sociology, and sociological work coming out of public health, medicine, and policy analysis. Of course, the divisions are fuzzy; old divisions have been eliminated: and support for them is waning. Many who do research and teaching in these areas, cross the boundary lines easily and with grace.

For example, as Collins ( 1989 ) pointed out, in some corners of the sociological landscape, the debates over whether sociology is a “science” are futile. With “science” mistakenly equated with quantitative research, Collins contends that sociology, like other sciences, engages in the “formulation of generalized principles, organized into models of the underlying processes that generate the social world” (Collins 1989 , p. 1124). Similarly, to righteously equate medical sociology only with publication in sociological journals, but not publication in the general or medical journals, is equally problematic. The problem is how, in this era of proliferating opportunities for sociologists in diverse employment positions and in a wider range of journals, can we take advantage of all of these contributions and pass them on to the next generation? Sociological knowledge can advance, as Collins ( 1989 ) notes, with a coherence of theoretical conceptions across different areas and methods of research. Critique is good, and something that sociologists are extraordinarily proficient in; but this is useful only to the purpose of moving our understanding of the world forward.

This volume is a first step, we hope, in facilitating that coherence by explicitly bringing together these three different strains of medical sociology, by bringing their authors in contact with one another, with other medical sociologists, and with the next generation of researchers. That is, we have tried to take direct account of the potential contributions from diverse vantage points on the landscape of sociology. Specifically, the editors have sought out contributions from each of the three communities of sociological research on health, illness, and healing, including making an attempt, albeit a preliminary one, to escape the surface of American medical sociology. We ignore where on the intellectual and field/subfield/disciplinary map they come from. In this way, we hope to complement the Handbook of Medical Sociology , now in its 6th edition, which has served since 1963 to represent the cutting edge of the subfield.

Organizing by Elevation

We organize the insights along a vertically integrated map that carries the spirit of C.W. Mills forward in acknowledging individuals and contexts. In fact, in this first section, we step back even from the map of sociology so as not to ignore two facts – other disciplines aim to understand the same phenomena as medical sociology, further complicating our task of surveying existing contributions and gathering “leads;” and the U.S. brand of medical sociology, and sociology in general, tends to take one kind of perspective that may have different contours from the uniquely salient insights brought by medical sociologists in other countries. Thus, Rogers and Pilgrim, from the University of Manchester and University of Central Lancashire, respectively, follow this introduction by demarcating our relationship to other sociomedical disciplines from the UK landscape. Most importantly, taking the case of mental health, psychiatry, and sociology, they examine how these disciplines approach the same problems, how they construct them, and whether their contributions even matter to “science.” They look at boundary disputes and collaborations as they have played out in the UK, arguing that boundaries have been movable historically. Conflicts and separation followed early conversations and collaboration. Yet, they see signs of a return to more congenial shared intellectual space that stems from the movement to an integrated team approach in treatment and new substantive “identities” like health services research which situate individuals of different approaches onto common property.

Whether the world is more complex, as globalization theorists claim, or the world of sociology has embraced greater complexity than it had when Mills wrote, the next chapter outlines the Network Episode Model – Phase III as a set of multiple contexts that are considered simultaneously as we proceed. While sociologists have always acknowledged multiple contexts, the NEM separates out macro-contexts that intersect and now, can be researched simultaneously, whether through team ethnography (Burton 2007 ; Newman et al. 2004 ) or through Hierarchical Linear Modeling (Xie and Hannum 1996 ). We also go to and beneath the micro-foundations of macro-sociology that Collins ( 1981 ) addressed. While our focus may be on the “illness career,” there are levels below the individual which have to be reckoned with if we are to get past the old nature vs. nurture dichotomies. Thus, while macro levels can match the cartographic metaphor more-or-less literally of “place,” the sociological insight of vertical integration also guide us to more micro levels below the surface of the individual (e.g., their genetic inheritance). But at each level, the NEM argues that sociology must explicitly measure contextual factors and the connecting mechanisms of influence, calling for multi-method approaches which maximize the ability of empirical research to match “the promise.”

This section ends with a critical assessment of the theory of fundamental causality and suggests several forward-looking research directions. Freese and Lutfey argue that the SES-health association has to be unpacked in each time and place. Yet, they also see this as insufficient because it fails to tell us why this link transcends time and place. This widespread association has to be confronted with universalities, distinctions, and tensions. Ending with a focus on future research, they point to the potential of looking both in structure and “under the skin” using the interplay of quantitative and qualitative methods and offering three considerations for medical sociology to more strongly influence health policy.

Connecting Communities

This section deals with “places” above the health care system, looking to comparisons across countries (Beckfield and Olafsdottir; Ruggie); organized individuals taking on health and health care issues in the public (Brown and colleagues), policy spheres (Ruggie), or those institutions outside medicine (Aldigé, Medina and McCranie). We start with a look across countries, the area of comparative health systems, where Ruggie argues that there may be those who remain dubious about lessons that can be learned from cross-national analyses. She aims to convince them, admirably so, by pointing to the well-known paradox that was alluded to earlier about the high spending of resources and the low level of return in the U.S. She identifies persistent barriers in aims and means that result in inequitable health care in the U.S. Ruggie outlines and documents eight lessons about health care systems that the U.S. can learn from the experience of other nations. She ends by pointing to the ubiquitous relationship between poverty and poor health, in all countries, and the final lesson which supports the role that efforts outside the health care system have in improving health outcomes. Beckfield and Olafsdottir push this further, arguing that the welfare state offers a window into understanding how societies organize their economic, political, and cultural landscape. In turn, different forms of social organization are critical to understanding the causes of health, illness, and healing, and how these reverberate through the lives of individuals and societies. They lay out types and mechanisms through politics, health institutions, and lay culture, offering a set of propositions and hypotheses that, if examined empirically, will push our understandings of macro-level factors and perhaps unearth new suggestions for social change.

Remaining with the influence of civil society, Brown and his colleagues target the increasing influence of health activists and the health social movements that they populate. Arguing that such efforts have increased in number and broadened medicine’s concern to include issues of justice, poverty, and toxic work conditions, they provide theoretical and analytic concepts on relevant collective actions. The concepts they find to hold the most potential – empowerment, movement-driven medicalization and disempowerment, institutional political economy, and lay-professional relationships – connect to each of the “above the individual” NEM levels. Their ecosocial view connects communities, inequalities and disproportionate exposure to toxic conditions (e.g., environmental hazards and stressors) that translate into health disparities and that set a broader territory for the institution of medicine, as well as for medical sociology.

The final two pieces examine the role of institutions outside of medicine as they work with and against the aims of the profession, its ancillary occupations, and its organizations. Medina and McCranie reopen the classic claim that medicine “won” jurisdiction over deviance, having first “dibs” to define it as a problem of disease, eliminating the power of law or religion over societal response (Freidson 1970 ). Looking to the case of psychopathy, they reconsider the meaning of medicalization and the potential of thinking about “layers” of control as a better fit in the contemporary era. Ending with a call for recognizing and researching the multiplicity of institutional responsibility, this piece provides the perfect lead-in to Alidgé’s summary of the insights from sociology’s long but fairly sparse line of research on the intersection of legal and medical control of mental illness. Focusing on the “collision” that occurred in the wake of the civil rights movement, Aldigé details the complex sociohistorical forces that have shaped and reshaped the points of strain and support between two major institutions of social control of deviance.

Connecting to Medicine: The Profession and Its Organizations

With the dominance of the concept of medicalization (Zola 1972 ; Conrad 2005 ) and its dissemination into scientific and public life, we asked Clarke and Shim, who had offered an extension of the concept (biomedicalization; Clarke et al. 2003 ), to step back, review the current status of different approaches, update us on their own thinking (including addressing the critiques), and craft one possible future agenda. Entering into this assessment from the view of the sociology of science and technology, rather than pure medical sociology per se, they explore the potential for building bridges across the terrains of medical sociology, medical anthropology, medicine, and other neighboring terrains that share a concern with understanding how the boundaries of medical jurisdiction expand.

Hafferty and Castellani push past issues of medicalization and pursue medical sociology’s attention to and then abandonment of interest in the profession of medicine. Ironically, they contend that after medical sociologists documented and debate the rise of the profession to dominance, the subfield (and the larger discipline) has missed the take-up by medicine itself of issues of “professionalism” in light of its acknowledgement of the role of larger contextual factors defining its work. This change reopens the call for a sociological perspective and they provide a roadmap. Part of sociology’s turn away from issues of the institutional situation of medicine meant that there has been little attention to the fate of women as doctors since Lorber and Moore’s ( 2002 ) pioneering 1984 study. Finally, Boulis and Jacobs give us an update on the status of women in medicine. Taking us past even the insights of their comprehensive project ( 2008 ), providing the necessary background to understand where women are in the profession, they elaborate on whether medicine’s early sexist climate has changed, even if only around the edges. In the end, they conclude that progress has been slow at best; and, if and how the profession changes vis-á-vis gender has more to do with structural pressures than changing values.

The final two chapters in this section move to the organization of the health care system itself, with Caronna asking about the socio-historical logics that have shaped and continue to shape medicine in the U.S., while Kronenfeld explores the absence, for the most part, of medical sociologists in research on central policy questions relevant to health and health care. The former, as Caronna herself indicates, can illuminate the past and shape the future. By emphasizing the complex web of trust issues necessary to maintain a health care system, she guides us through the three logics of the past and asks whether we are entering a fourth, calling for more sociological research. Kronenfeld refutes the idea that policy studies belong to political science, staking sociology’s claim by surveying the past meaning and emphases of health care policy-making processes and noting a lacunae of broad system level analyses.

Connecting to the People: The Public as Patient and Powerful Force

This fourth section targets individuals outside the health care system as they interact with and affect it. Figert begins this journey through the community, asking whether or not medicalization theory has underplayed the potential of lay individuals in the medicalization process. The thread of reevaluating our theoretical concepts that revolve around professional power continues, with a reconsideration of Zola, Conrad, Clarke, and Epstein but expanding consideration to a more explicit role of expertise. This includes the expertise of the lay person as well as the expertise of professionals, noting that much current discussion debates the influence of the former. Tying into the earlier chapters by Brown and colleagues, she brings up how social movements may have shifted the landscape of medicine, and she reminds us of the formality of the classic formulations in Parsons’ patient role. This opens the path for May’s reformulation of Parsons’ “vision” of the physician–patient interaction. While recognizing that the organization of health care matters because it penetrates the clinical encounter, May targets the social relationship in the clinic as the place where their effects are mobilized and enacted. The arrival of “disease management” and “self-management” have become a routine part of “mundane medicine,” the care that comes with the greater prominence of chronic illness and disease. Digging further into the encounter, Heritage and Maynard review research from process, discourse, and conversational analyses that reveal in detail how the clinical encounter proceeds, what its key turning points are, and how there has been a clear and gradual movement to greater power balance between physicians and patients. Finally, Wright acknowledges that technological advances have widened the examination room, bringing with them greater expertise but also challenges from the public. With electronic records and publically available health information technology, Wright argues that sociologists should track the ramifications of these changes on trust, confidentiality, authority, and the social dynamics of how information is collected, managed, and used by both providers and their clients.

Connecting Personal and Cultural Systems

Much of the interest in the social sciences of late stems from the concern with health disparities. Alegría and her colleagues take this on in a holistic fashion, offering a larger framework within which to develop hypotheses and measures. Drawing from the notion of cumulative disadvantage across time and levels of organization, the Social Cultural Framework for Health Care Disparities serves to guide further and more integrated studies. They set the stage for more specific concerns. Among these, areas that continue to attract research attention are race and gender. In a review of the black–white differences in health, Jackson and Cummings point to the paradox of the Black middle class. Counterintuitive to the SES-health gradient, they provide evidence that the Black middle class does not fare better in health status than the White lower class, and end by suggesting that accumulated network capital, limited by residential segregation, is ripe for future research. In a similar vein, Read and Gorman turn their attention to gender. They give an overview of what we know about male–female differences in mortality and morbidity, theories used to explain these, and three challenges that remain in the gendered profile of health – immigration, the life course, and co-morbidities between mental and physical health. To assist in future research, the final note in this section involves methods for unraveling the mechanisms that underlie many of the associations that have been documented. Pairing sociologists who come from different methodological corners of the sociological landscape, Watkins, Swidler and Biruk describe and illustrate the use of “hearsay ethnography.” Relying on individuals in the communities they study to hear and record what their social network ties discuss, they show the advantages over traditional survey and ethnographic methods in gathering data on “meaning” in everyday life.

Connecting to Dynamics: The Health and Illness Career