- Craft and Criticism

- Fiction and Poetry

- News and Culture

- Lit Hub Radio

- Reading Lists

- Literary Criticism

- Craft and Advice

- In Conversation

- On Translation

- Short Story

- From the Novel

- Bookstores and Libraries

- Film and TV

- Art and Photography

- Freeman’s

- The Virtual Book Channel

- Behind the Mic

- Beyond the Page

- The Cosmic Library

- The Critic and Her Publics

- Emergence Magazine

- Fiction/Non/Fiction

- First Draft: A Dialogue on Writing

- The History of Literature

- I’m a Writer But

- Lit Century

- Tor Presents: Voyage Into Genre

- Windham-Campbell Prizes Podcast

- Write-minded

- The Best of the Decade

- Best Reviewed Books

- BookMarks Daily Giveaway

- The Daily Thrill

- CrimeReads Daily Giveaway

The 10 Best Essay Collections of the Decade

Ever tried. ever failed. no matter..

Friends, it’s true: the end of the decade approaches. It’s been a difficult, anxiety-provoking, morally compromised decade, but at least it’s been populated by some damn fine literature. We’ll take our silver linings where we can.

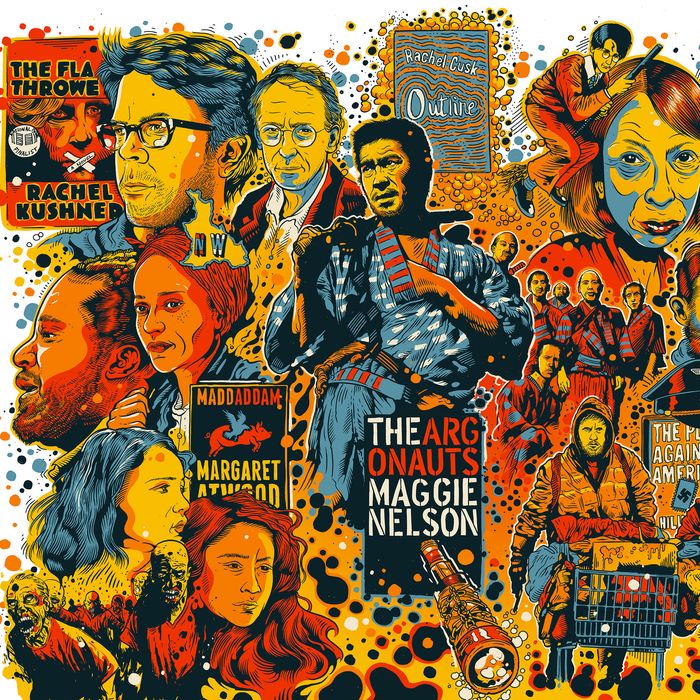

So, as is our hallowed duty as a literary and culture website—though with full awareness of the potentially fruitless and endlessly contestable nature of the task—in the coming weeks, we’ll be taking a look at the best and most important (these being not always the same) books of the decade that was. We will do this, of course, by means of a variety of lists. We began with the best debut novels , the best short story collections , the best poetry collections , and the best memoirs of the decade , and we have now reached the fifth list in our series: the best essay collections published in English between 2010 and 2019.

The following books were chosen after much debate (and several rounds of voting) by the Literary Hub staff. Tears were spilled, feelings were hurt, books were re-read. And as you’ll shortly see, we had a hard time choosing just ten—so we’ve also included a list of dissenting opinions, and an even longer list of also-rans. As ever, free to add any of your own favorites that we’ve missed in the comments below.

The Top Ten

Oliver sacks, the mind’s eye (2010).

Toward the end of his life, maybe suspecting or sensing that it was coming to a close, Dr. Oliver Sacks tended to focus his efforts on sweeping intellectual projects like On the Move (a memoir), The River of Consciousness (a hybrid intellectual history), and Hallucinations (a book-length meditation on, what else, hallucinations). But in 2010, he gave us one more classic in the style that first made him famous, a form he revolutionized and brought into the contemporary literary canon: the medical case study as essay. In The Mind’s Eye , Sacks focuses on vision, expanding the notion to embrace not only how we see the world, but also how we map that world onto our brains when our eyes are closed and we’re communing with the deeper recesses of consciousness. Relaying histories of patients and public figures, as well as his own history of ocular cancer (the condition that would eventually spread and contribute to his death), Sacks uses vision as a lens through which to see all of what makes us human, what binds us together, and what keeps us painfully apart. The essays that make up this collection are quintessential Sacks: sensitive, searching, with an expertise that conveys scientific information and experimentation in terms we can not only comprehend, but which also expand how we see life carrying on around us. The case studies of “Stereo Sue,” of the concert pianist Lillian Kalir, and of Howard, the mystery novelist who can no longer read, are highlights of the collection, but each essay is a kind of gem, mined and polished by one of the great storytellers of our era. –Dwyer Murphy, CrimeReads Managing Editor

John Jeremiah Sullivan, Pulphead (2011)

The American essay was having a moment at the beginning of the decade, and Pulphead was smack in the middle. Without any hard data, I can tell you that this collection of John Jeremiah Sullivan’s magazine features—published primarily in GQ , but also in The Paris Review , and Harper’s —was the only full book of essays most of my literary friends had read since Slouching Towards Bethlehem , and probably one of the only full books of essays they had even heard of.

Well, we all picked a good one. Every essay in Pulphead is brilliant and entertaining, and illuminates some small corner of the American experience—even if it’s just one house, with Sullivan and an aging writer inside (“Mr. Lytle” is in fact a standout in a collection with no filler; fittingly, it won a National Magazine Award and a Pushcart Prize). But what are they about? Oh, Axl Rose, Christian Rock festivals, living around the filming of One Tree Hill , the Tea Party movement, Michael Jackson, Bunny Wailer, the influence of animals, and by god, the Miz (of Real World/Road Rules Challenge fame).

But as Dan Kois has pointed out , what connects these essays, apart from their general tone and excellence, is “their author’s essential curiosity about the world, his eye for the perfect detail, and his great good humor in revealing both his subjects’ and his own foibles.” They are also extremely well written, drawing much from fictional techniques and sentence craft, their literary pleasures so acute and remarkable that James Wood began his review of the collection in The New Yorker with a quiz: “Are the following sentences the beginnings of essays or of short stories?” (It was not a hard quiz, considering the context.)

It’s hard not to feel, reading this collection, like someone reached into your brain, took out the half-baked stuff you talk about with your friends, researched it, lived it, and represented it to you smarter and better and more thoroughly than you ever could. So read it in awe if you must, but read it. –Emily Temple, Senior Editor

Aleksandar Hemon, The Book of My Lives (2013)

Such is the sentence-level virtuosity of Aleksandar Hemon—the Bosnian-American writer, essayist, and critic—that throughout his career he has frequently been compared to the granddaddy of borrowed language prose stylists: Vladimir Nabokov. While it is, of course, objectively remarkable that anyone could write so beautifully in a language they learned in their twenties, what I admire most about Hemon’s work is the way in which he infuses every essay and story and novel with both a deep humanity and a controlled (but never subdued) fury. He can also be damn funny. Hemon grew up in Sarajevo and left in 1992 to study in Chicago, where he almost immediately found himself stranded, forced to watch from afar as his beloved home city was subjected to a relentless four-year bombardment, the longest siege of a capital in the history of modern warfare. This extraordinary memoir-in-essays is many things: it’s a love letter to both the family that raised him and the family he built in exile; it’s a rich, joyous, and complex portrait of a place the 90s made synonymous with war and devastation; and it’s an elegy for the wrenching loss of precious things. There’s an essay about coming of age in Sarajevo and another about why he can’t bring himself to leave Chicago. There are stories about relationships forged and maintained on the soccer pitch or over the chessboard, and stories about neighbors and mentors turned monstrous by ethnic prejudice. As a chorus they sing with insight, wry humor, and unimaginable sorrow. I am not exaggerating when I say that the collection’s devastating final piece, “The Aquarium”—which details his infant daughter’s brain tumor and the agonizing months which led up to her death—remains the most painful essay I have ever read. –Dan Sheehan, Book Marks Editor

Robin Wall Kimmerer, Braiding Sweetgrass (2013)

Of every essay in my relentlessly earmarked copy of Braiding Sweetgrass , Dr. Robin Wall Kimmerer’s gorgeously rendered argument for why and how we should keep going, there’s one that especially hits home: her account of professor-turned-forester Franz Dolp. When Dolp, several decades ago, revisited the farm that he had once shared with his ex-wife, he found a scene of destruction: The farm’s new owners had razed the land where he had tried to build a life. “I sat among the stumps and the swirling red dust and I cried,” he wrote in his journal.

So many in my generation (and younger) feel this kind of helplessness–and considerable rage–at finding ourselves newly adult in a world where those in power seem determined to abandon or destroy everything that human bodies have always needed to survive: air, water, land. Asking any single book to speak to this helplessness feels unfair, somehow; yet, Braiding Sweetgrass does, by weaving descriptions of indigenous tradition with the environmental sciences in order to show what survival has looked like over the course of many millennia. Kimmerer’s essays describe her personal experience as a Potawotami woman, plant ecologist, and teacher alongside stories of the many ways that humans have lived in relationship to other species. Whether describing Dolp’s work–he left the stumps for a life of forest restoration on the Oregon coast–or the work of others in maple sugar harvesting, creating black ash baskets, or planting a Three Sisters garden of corn, beans, and squash, she brings hope. “In ripe ears and swelling fruit, they counsel us that all gifts are multiplied in relationship,” she writes of the Three Sisters, which all sustain one another as they grow. “This is how the world keeps going.” –Corinne Segal, Senior Editor

Hilton Als, White Girls (2013)

In a world where we are so often reduced to one essential self, Hilton Als’ breathtaking book of critical essays, White Girls , which meditates on the ways he and other subjects read, project and absorb parts of white femininity, is a radically liberating book. It’s one of the only works of critical thinking that doesn’t ask the reader, its author or anyone he writes about to stoop before the doorframe of complete legibility before entering. Something he also permitted the subjects and readers of his first book, the glorious book-length essay, The Women , a series of riffs and psychological portraits of Dorothy Dean, Owen Dodson, and the author’s own mother, among others. One of the shifts of that book, uncommon at the time, was how it acknowledges the way we inhabit bodies made up of variously gendered influences. To read White Girls now is to experience the utter freedom of this gift and to marvel at Als’ tremendous versatility and intelligence.

He is easily the most diversely talented American critic alive. He can write into genres like pop music and film where being part of an audience is a fantasy happening in the dark. He’s also wired enough to know how the art world builds reputations on the nod of rich white patrons, a significant collision in a time when Jean-Michel Basquiat is America’s most expensive modern artist. Als’ swerving and always moving grip on performance means he’s especially good on describing the effect of art which is volatile and unstable and built on the mingling of made-up concepts and the hard fact of their effect on behavior, such as race. Writing on Flannery O’Connor for instance he alone puts a finger on her “uneasy and unavoidable union between black and white, the sacred and the profane, the shit and the stars.” From Eminem to Richard Pryor, André Leon Talley to Michael Jackson, Als enters the life and work of numerous artists here who turn the fascinations of race and with whiteness into fury and song and describes the complexity of their beauty like his life depended upon it. There are also brief memoirs here that will stop your heart. This is an essential work to understanding American culture. –John Freeman, Executive Editor

Eula Biss, On Immunity (2014)

We move through the world as if we can protect ourselves from its myriad dangers, exercising what little agency we have in an effort to keep at bay those fears that gather at the edges of any given life: of loss, illness, disaster, death. It is these fears—amplified by the birth of her first child—that Eula Biss confronts in her essential 2014 essay collection, On Immunity . As any great essayist does, Biss moves outward in concentric circles from her own very private view of the world to reveal wider truths, discovering as she does a culture consumed by anxiety at the pervasive toxicity of contemporary life. As Biss interrogates this culture—of privilege, of whiteness—she interrogates herself, questioning the flimsy ways in which we arm ourselves with science or superstition against the impurities of daily existence.

Five years on from its publication, it is dismaying that On Immunity feels as urgent (and necessary) a defense of basic science as ever. Vaccination, we learn, is derived from vacca —for cow—after the 17th-century discovery that a small application of cowpox was often enough to inoculate against the scourge of smallpox, an etymological digression that belies modern conspiratorial fears of Big Pharma and its vaccination agenda. But Biss never scolds or belittles the fears of others, and in her generosity and openness pulls off a neat (and important) trick: insofar as we are of the very world we fear, she seems to be suggesting, we ourselves are impure, have always been so, permeable, vulnerable, yet so much stronger than we think. –Jonny Diamond, Editor-in-Chief

Rebecca Solnit, The Mother of All Questions (2016)

When Rebecca Solnit’s essay, “Men Explain Things to Me,” was published in 2008, it quickly became a cultural phenomenon unlike almost any other in recent memory, assigning language to a behavior that almost every woman has witnessed—mansplaining—and, in the course of identifying that behavior, spurring a movement, online and offline, to share the ways in which patriarchal arrogance has intersected all our lives. (It would also come to be the titular essay in her collection published in 2014.) The Mother of All Questions follows up on that work and takes it further in order to examine the nature of self-expression—who is afforded it and denied it, what institutions have been put in place to limit it, and what happens when it is employed by women. Solnit has a singular gift for describing and decoding the misogynistic dynamics that govern the world so universally that they can seem invisible and the gendered violence that is so common as to seem unremarkable; this naming is powerful, and it opens space for sharing the stories that shape our lives.

The Mother of All Questions, comprised of essays written between 2014 and 2016, in many ways armed us with some of the tools necessary to survive the gaslighting of the Trump years, in which many of us—and especially women—have continued to hear from those in power that the things we see and hear do not exist and never existed. Solnit also acknowledges that labels like “woman,” and other gendered labels, are identities that are fluid in reality; in reviewing the book for The New Yorker , Moira Donegan suggested that, “One useful working definition of a woman might be ‘someone who experiences misogyny.'” Whichever words we use, Solnit writes in the introduction to the book that “when words break through unspeakability, what was tolerated by a society sometimes becomes intolerable.” This storytelling work has always been vital; it continues to be vital, and in this book, it is brilliantly done. –Corinne Segal, Senior Editor

Valeria Luiselli, Tell Me How It Ends (2017)

The newly minted MacArthur fellow Valeria Luiselli’s four-part (but really six-part) essay Tell Me How It Ends: An Essay in Forty Questions was inspired by her time spent volunteering at the federal immigration court in New York City, working as an interpreter for undocumented, unaccompanied migrant children who crossed the U.S.-Mexico border. Written concurrently with her novel Lost Children Archive (a fictional exploration of the same topic), Luiselli’s essay offers a fascinating conceit, the fashioning of an argument from the questions on the government intake form given to these children to process their arrivals. (Aside from the fact that this essay is a heartbreaking masterpiece, this is such a good conceit—transforming a cold, reproducible administrative document into highly personal literature.) Luiselli interweaves a grounded discussion of the questionnaire with a narrative of the road trip Luiselli takes with her husband and family, across America, while they (both Mexican citizens) wait for their own Green Card applications to be processed. It is on this trip when Luiselli reflects on the thousands of migrant children mysteriously traveling across the border by themselves. But the real point of the essay is to actually delve into the real stories of some of these children, which are agonizing, as well as to gravely, clearly expose what literally happens, procedural, when they do arrive—from forms to courts, as they’re swallowed by a bureaucratic vortex. Amid all of this, Luiselli also takes on more, exploring the larger contextual relationship between the United States of America and Mexico (as well as other countries in Central America, more broadly) as it has evolved to our current, adverse moment. Tell Me How It Ends is so small, but it is so passionate and vigorous: it desperately accomplishes in its less-than-100-pages-of-prose what centuries and miles and endless records of federal bureaucracy have never been able, and have never cared, to do: reverse the dehumanization of Latin American immigrants that occurs once they set foot in this country. –Olivia Rutigliano, CrimeReads Editorial Fellow

Zadie Smith, Feel Free (2018)

In the essay “Meet Justin Bieber!” in Feel Free , Zadie Smith writes that her interest in Justin Bieber is not an interest in the interiority of the singer himself, but in “the idea of the love object”. This essay—in which Smith imagines a meeting between Bieber and the late philosopher Martin Buber (“Bieber and Buber are alternative spellings of the same German surname,” she explains in one of many winning footnotes. “Who am I to ignore these hints from the universe?”). Smith allows that this premise is a bit premise -y: “I know, I know.” Still, the resulting essay is a very funny, very smart, and un-tricky exploration of individuality and true “meeting,” with a dash of late capitalism thrown in for good measure. The melding of high and low culture is the bread and butter of pretty much every prestige publication on the internet these days (and certainly of the Twitter feeds of all “public intellectuals”), but the essays in Smith’s collection don’t feel familiar—perhaps because hers is, as we’ve long known, an uncommon skill. Though I believe Smith could probably write compellingly about anything, she chooses her subjects wisely. She writes with as much electricity about Brexit as the aforementioned Beliebers—and each essay is utterly engrossing. “She contains multitudes, but her point is we all do,” writes Hermione Hoby in her review of the collection in The New Republic . “At the same time, we are, in our endless difference, nobody but ourselves.” –Jessie Gaynor, Social Media Editor

Tressie McMillan Cottom, Thick: And Other Essays (2019)

Tressie McMillan Cottom is an academic who has transcended the ivory tower to become the sort of public intellectual who can easily appear on radio or television talk shows to discuss race, gender, and capitalism. Her collection of essays reflects this duality, blending scholarly work with memoir to create a collection on the black female experience in postmodern America that’s “intersectional analysis with a side of pop culture.” The essays range from an analysis of sexual violence, to populist politics, to social media, but in centering her own experiences throughout, the collection becomes something unlike other pieces of criticism of contemporary culture. In explaining the title, she reflects on what an editor had said about her work: “I was too readable to be academic, too deep to be popular, too country black to be literary, and too naïve to show the rigor of my thinking in the complexity of my prose. I had wanted to create something meaningful that sounded not only like me, but like all of me. It was too thick.” One of the most powerful essays in the book is “Dying to be Competent” which begins with her unpacking the idiocy of LinkedIn (and the myth of meritocracy) and ends with a description of her miscarriage, the mishandling of black woman’s pain, and a condemnation of healthcare bureaucracy. A finalist for the 2019 National Book Award for Nonfiction, Thick confirms McMillan Cottom as one of our most fearless public intellectuals and one of the most vital. –Emily Firetog, Deputy Editor

Dissenting Opinions

The following books were just barely nudged out of the top ten, but we (or at least one of us) couldn’t let them pass without comment.

Elif Batuman, The Possessed (2010)

In The Possessed Elif Batuman indulges her love of Russian literature and the result is hilarious and remarkable. Each essay of the collection chronicles some adventure or other that she had while in graduate school for Comparative Literature and each is more unpredictable than the next. There’s the time a “well-known 20th-centuryist” gave a graduate student the finger; and the time when Batuman ended up living in Samarkand, Uzbekistan, for a summer; and the time that she convinced herself Tolstoy was murdered and spent the length of the Tolstoy Conference in Yasnaya Polyana considering clues and motives. Rich in historic detail about Russian authors and literature and thoughtfully constructed, each essay is an amalgam of critical analysis, cultural criticism, and serious contemplation of big ideas like that of identity, intellectual legacy, and authorship. With wit and a serpentine-like shape to her narratives, Batuman adopts a form reminiscent of a Socratic discourse, setting up questions at the beginning of her essays and then following digressions that more or less entreat the reader to synthesize the answer for herself. The digressions are always amusing and arguably the backbone of the collection, relaying absurd anecdotes with foreign scholars or awkward, surreal encounters with Eastern European strangers. Central also to the collection are Batuman’s intellectual asides where she entertains a theory—like the “problem of the person”: the inability to ever wholly capture one’s character—that ultimately layer the book’s themes. “You are certainly my most entertaining student,” a professor said to Batuman. But she is also curious and enthusiastic and reflective and so knowledgeable that she might even convince you (she has me!) that you too love Russian literature as much as she does. –Eleni Theodoropoulos, Editorial Fellow

Roxane Gay, Bad Feminist (2014)

Roxane Gay’s now-classic essay collection is a book that will make you laugh, think, cry, and then wonder, how can cultural criticism be this fun? My favorite essays in the book include Gay’s musings on competitive Scrabble, her stranded-in-academia dispatches, and her joyous film and television criticism, but given the breadth of topics Roxane Gay can discuss in an entertaining manner, there’s something for everyone in this one. This book is accessible because feminism itself should be accessible – Roxane Gay is as likely to draw inspiration from YA novels, or middle-brow shows about friendship, as she is to introduce concepts from the academic world, and if there’s anyone I trust to bridge the gap between high culture, low culture, and pop culture, it’s the Goddess of Twitter. I used to host a book club dedicated to radical reads, and this was one of the first picks for the club; a week after the book club met, I spied a few of the attendees meeting in the café of the bookstore, and found out that they had bonded so much over discussing Bad Feminist that they couldn’t wait for the next meeting of the book club to keep discussing politics and intersectionality, and that, in a nutshell, is the power of Roxane. –Molly Odintz, CrimeReads Associate Editor

Rivka Galchen, Little Labors (2016)

Generally, I find stories about the trials and tribulations of child-having to be of limited appeal—useful, maybe, insofar as they offer validation that other people have also endured the bizarre realities of living with a tiny human, but otherwise liable to drift into the musings of parents thrilled at the simple fact of their own fecundity, as if they were the first ones to figure the process out (or not). But Little Labors is not simply an essay collection about motherhood, perhaps because Galchen initially “didn’t want to write about” her new baby—mostly, she writes, “because I had never been interested in babies, or mothers; in fact, those subjects had seemed perfectly not interesting to me.” Like many new mothers, though, Galchen soon discovered her baby—which she refers to sometimes as “the puma”—to be a preoccupying thought, demanding to be written about. Galchen’s interest isn’t just in her own progeny, but in babies in literature (“Literature has more dogs than babies, and also more abortions”), The Pillow Book , the eleventh-century collection of musings by Sei Shōnagon, and writers who are mothers. There are sections that made me laugh out loud, like when Galchen continually finds herself in an elevator with a neighbor who never fails to remark on the puma’s size. There are also deeper, darker musings, like the realization that the baby means “that it’s not permissible to die. There are days when this does not feel good.” It is a slim collection that I happened to read at the perfect time, and it remains one of my favorites of the decade. –Emily Firetog, Deputy Editor

Charlie Fox, This Young Monster (2017)

On social media as in his writing, British art critic Charlie Fox rejects lucidity for allusion and doesn’t quite answer the Twitter textbox’s persistent question: “What’s happening?” These days, it’s hard to tell. This Young Monster (2017), Fox’s first book,was published a few months after Donald Trump’s election, and at one point Fox takes a swipe at a man he judges “direct from a nightmare and just a repulsive fucking goon.” Fox doesn’t linger on politics, though, since most of the monsters he looks at “embody otherness and make it into art, ripping any conventional idea of beauty to shreds and replacing it with something weird and troubling of their own invention.”

If clichés are loathed because they conform to what philosopher Georges Bataille called “the common measure,” then monsters are rebellious non-sequiturs, comedic or horrific derailments from a classical ideal. Perverts in the most literal sense, monsters have gone astray from some “proper” course. The book’s nine chapters, which are about a specific monster or type of monster, are full of callbacks to familiar and lesser-known media. Fox cites visual art, film, songs, and books with the screwy buoyancy of a savant. Take one of his essays, “Spook House,” framed as a stage play with two principal characters, Klaus (“an intoxicated young skinhead vampire”) and Hermione (“a teen sorceress with green skin and jet-black hair” who looks more like The Wicked Witch than her namesake). The chorus is a troupe of trick-or-treaters. Using the filmmaker Cameron Jamie as a starting point, the rest is free association on gothic decadence and Detroit and L.A. as cities of the dead. All the while, Klaus quotes from Artforum , Dazed & Confused , and Time Out. It’s a technical feat that makes fictionalized dialogue a conveyor belt for cultural criticism.

In Fox’s imagination, David Bowie and the Hydra coexist alongside Peter Pan, Dennis Hopper, and the maenads. Fox’s book reaches for the monster’s mask, not really to peel it off but to feel and smell the rubber schnoz, to know how it’s made before making sure it’s still snugly set. With a stylistic blend of arthouse suavity and B-movie chic, This Young Monster considers how monsters in culture are made. Aren’t the scariest things made in post-production? Isn’t the creature just duplicity, like a looping choir or a dubbed scream? –Aaron Robertson, Assistant Editor

Elena Passarello, Animals Strike Curious Poses (2017)

Elena Passarello’s collection of essays Animals Strike Curious Poses picks out infamous animals and grants them the voice, narrative, and history they deserve. Not only is a collection like this relevant during the sixth extinction but it is an ambitious historical and anthropological undertaking, which Passarello has tackled with thorough research and a playful tone that rather than compromise her subject, complicates and humanizes it. Passarello’s intention is to investigate the role of animals across the span of human civilization and in doing so, to construct a timeline of humanity as told through people’s interactions with said animals. “Of all the images that make our world, animal images are particularly buried inside us,” Passarello writes in her first essay, to introduce us to the object of the book and also to the oldest of her chosen characters: Yuka, a 39,000-year-old mummified woolly mammoth discovered in the Siberian permafrost in 2010. It was an occasion so remarkable and so unfathomable given the span of human civilization that Passarello says of Yuka: “Since language is epically younger than both thought and experience, ‘woolly mammoth’ means, to a human brain, something more like time.” The essay ends with a character placing a hand on a cave drawing of a woolly mammoth, accompanied by a phrase which encapsulates the author’s vision for the book: “And he becomes the mammoth so he can envision the mammoth.” In Passarello’s hands the imagined boundaries between the animal, natural, and human world disintegrate and what emerges is a cohesive if baffling integrated history of life. With the accuracy and tenacity of a journalist and the spirit of a storyteller, Elena Passarello has assembled a modern bestiary worthy of contemplation and awe. –Eleni Theodoropoulos, Editorial Fellow

Esmé Weijun Wang, The Collected Schizophrenias (2019)

Esmé Weijun Wang’s collection of essays is a kaleidoscopic look at mental health and the lives affected by the schizophrenias. Each essay takes on a different aspect of the topic, but you’ll want to read them together for a holistic perspective. Esmé Weijun Wang generously begins The Collected Schizophrenias by acknowledging the stereotype, “Schizophrenia terrifies. It is the archetypal disorder of lunacy.” From there, she walks us through the technical language, breaks down the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual ( DSM-5 )’s clinical definition. And then she gets very personal, telling us about how she came to her own diagnosis and the way it’s touched her daily life (her relationships, her ideas about motherhood). Esmé Weijun Wang is uniquely situated to write about this topic. As a former lab researcher at Stanford, she turns a precise, analytical eye to her experience while simultaneously unfolding everything with great patience for her reader. Throughout, she brilliantly dissects the language around mental health. (On saying “a person living with bipolar disorder” instead of using “bipolar” as the sole subject: “…we are not our diseases. We are instead individuals with disorders and malfunctions. Our conditions lie over us like smallpox blankets; we are one thing and the illness is another.”) She pinpoints the ways she arms herself against anticipated reactions to the schizophrenias: high fashion, having attended an Ivy League institution. In a particularly piercing essay, she traces mental illness back through her family tree. She also places her story within more mainstream cultural contexts, calling on groundbreaking exposés about the dangerous of institutionalization and depictions of mental illness in television and film (like the infamous Slender Man case, in which two young girls stab their best friend because an invented Internet figure told them to). At once intimate and far-reaching, The Collected Schizophrenias is an informative and important (and let’s not forget artful) work. I’ve never read a collection quite so beautifully-written and laid-bare as this. –Katie Yee, Book Marks Assistant Editor

Ross Gay, The Book of Delights (2019)

When Ross Gay began writing what would become The Book of Delights, he envisioned it as a project of daily essays, each focused on a moment or point of delight in his day. This plan quickly disintegrated; on day four, he skipped his self-imposed assignment and decided to “in honor and love, delight in blowing it off.” (Clearly, “blowing it off” is a relative term here, as he still produced the book.) Ross Gay is a generous teacher of how to live, and this moment of reveling in self-compassion is one lesson among many in The Book of Delights , which wanders from moments of connection with strangers to a shade of “red I don’t think I actually have words for,” a text from a friend reading “I love you breadfruit,” and “the sun like a guiding hand on my back, saying everything is possible. Everything .”

Gay does not linger on any one subject for long, creating the sense that delight is a product not of extenuating circumstances, but of our attention; his attunement to the possibilities of a single day, and awareness of all the small moments that produce delight, are a model for life amid the warring factions of the attention economy. These small moments range from the physical–hugging a stranger, transplanting fig cuttings–to the spiritual and philosophical, giving the impression of sitting beside Gay in his garden as he thinks out loud in real time. It’s a privilege to listen. –Corinne Segal, Senior Editor

Honorable Mentions

A selection of other books that we seriously considered for both lists—just to be extra about it (and because decisions are hard).

Terry Castle, The Professor and Other Writings (2010) · Joyce Carol Oates, In Rough Country (2010) · Geoff Dyer, Otherwise Known as the Human Condition (2011) · Christopher Hitchens, Arguably (2011) · Roberto Bolaño, tr. Natasha Wimmer, Between Parentheses (2011) · Dubravka Ugresic, tr. David Williams, Karaoke Culture (2011) · Tom Bissell, Magic Hours (2012) · Kevin Young, The Grey Album (2012) · William H. Gass, Life Sentences: Literary Judgments and Accounts (2012) · Mary Ruefle, Madness, Rack, and Honey (2012) · Herta Müller, tr. Geoffrey Mulligan, Cristina and Her Double (2013) · Leslie Jamison, The Empathy Exams (2014) · Meghan Daum, The Unspeakable (2014) · Daphne Merkin, The Fame Lunches (2014) · Charles D’Ambrosio, Loitering (2015) · Wendy Walters, Multiply/Divide (2015) · Colm Tóibín, On Elizabeth Bishop (2015) · Renee Gladman, Calamities (2016) · Jesmyn Ward, ed. The Fire This Time (2016) · Lindy West, Shrill (2016) · Mary Oliver, Upstream (2016) · Emily Witt, Future Sex (2016) · Olivia Laing, The Lonely City (2016) · Mark Greif, Against Everything (2016) · Durga Chew-Bose, Too Much and Not the Mood (2017) · Sarah Gerard, Sunshine State (2017) · Jim Harrison, A Really Big Lunch (2017) · J.M. Coetzee, Late Essays: 2006-2017 (2017) · Melissa Febos, Abandon Me (2017) · Louise Glück, American Originality (2017) · Joan Didion, South and West (2017) · Tom McCarthy, Typewriters, Bombs, Jellyfish (2017) · Hanif Abdurraqib, They Can’t Kill Us Until they Kill Us (2017) · Ta-Nehisi Coates, We Were Eight Years in Power (2017) · Samantha Irby, We Are Never Meeting in Real Life (2017) · Alexander Chee, How to Write an Autobiographical Novel (2018) · Alice Bolin, Dead Girls (2018) · Marilynne Robinson, What Are We Doing Here? (2018) · Lorrie Moore, See What Can Be Done (2018) · Maggie O’Farrell, I Am I Am I Am (2018) · Ijeoma Oluo, So You Want to Talk About Race (2018) · Rachel Cusk, Coventry (2019) · Jia Tolentino, Trick Mirror (2019) · Emily Bernard, Black is the Body (2019) · Toni Morrison, The Source of Self-Regard (2019) · Margaret Renkl, Late Migrations (2019) · Rachel Munroe, Savage Appetites (2019) · Robert A. Caro, Working (2019) · Arundhati Roy, My Seditious Heart (2019).

Emily Temple

Previous article, next article.

- RSS - Posts

Literary Hub

Created by Grove Atlantic and Electric Literature

Sign Up For Our Newsletters

How to Pitch Lit Hub

Advertisers: Contact Us

Privacy Policy

Support Lit Hub - Become A Member

Become a Lit Hub Supporting Member : Because Books Matter

For the past decade, Literary Hub has brought you the best of the book world for free—no paywall. But our future relies on you. In return for a donation, you’ll get an ad-free reading experience , exclusive editors’ picks, book giveaways, and our coveted Joan Didion Lit Hub tote bag . Most importantly, you’ll keep independent book coverage alive and thriving on the internet.

Become a member for as low as $5/month

Essay on 21st Century Literature

Students are often asked to write an essay on 21st Century Literature in their schools and colleges. And if you’re also looking for the same, we have created 100-word, 250-word, and 500-word essays on the topic.

Let’s take a look…

100 Words Essay on 21st Century Literature

What is 21st century literature.

21st Century Literature is writing from the year 2000 onwards. It includes novels, poems, and plays. This period is marked by the use of digital technology and cultural diversity. Writers use the internet to share their work. They also explore themes like identity, globalization, and technology.

Features of 21st Century Literature

This literature is known for its variety. It has a mix of different styles, genres, and themes. Many books deal with real-world issues. They talk about politics, social changes, and personal struggles. Writers use simple language to express complex ideas.

Impact of Technology

Technology has a big role in this literature. Writers use it to create new forms of storytelling. E-books and audiobooks are popular. Online platforms allow writers to reach a global audience. They can also interact with readers in real-time.

Representation and Diversity

21st Century Literature is rich in diversity. It includes voices from different cultures, races, and genders. This literature challenges old ideas and promotes equality. It helps us understand different perspectives and experiences.

250 Words Essay on 21st Century Literature

Introduction to 21st century literature.

21st century literature is the writing that’s been created from the year 2000 to now. It’s a time of great change and new thoughts. It’s a time when writers have more freedom and creativity than ever before.

One key feature of 21st century literature is diversity. Many writers from different backgrounds, cultures, and experiences are sharing their stories. This means you’ll find books about all kinds of people and places.

Technology’s Impact

Technology has also played a big role in shaping 21st century literature. With the internet and social media, writers can share their work with the world instantly. This has led to new types of writing, like blogs and tweets, becoming part of literature.

Themes and Genres

In terms of themes, 21st century literature often deals with issues like identity, diversity, and change. Also, many new genres have emerged, such as young adult fiction and graphic novels.

In conclusion, 21st century literature is rich and diverse. It reflects our changing world and the many voices within it. It’s an exciting time to be a reader and a writer.

500 Words Essay on 21st Century Literature

Topics and themes.

One of the key features of 21st Century Literature is the variety of topics it covers. Writers from all over the world have been telling stories about different cultures, experiences, and views. Many books talk about important issues like climate change, social justice, and mental health. These are topics that people care about a lot today.

Style and Form

The way stories are told in 21st Century Literature is also very different. Writers have been playing with the form and structure of their books. Some books might not have a clear start, middle, and end. Others might use different points of view or mix up the timeline. This makes the books more interesting and gives readers new ways to think about the story.

Influence of Technology

21st Century Literature is also known for its focus on representation and diversity. Writers are telling stories about people from all walks of life. This includes people of different races, religions, genders, and sexual orientations. These stories help us understand and appreciate the experiences of people who might be different from us.

In conclusion, 21st Century Literature is a rich and exciting field. It covers a wide range of topics and uses new and innovative ways to tell stories. It’s influenced by technology and focused on representation and diversity. As readers, we’re lucky to have so many interesting books to choose from. As we move further into the 21st Century, it will be exciting to see how literature continues to evolve.

Apart from these, you can look at all the essays by clicking here .

Happy studying!

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Part 4: Romantic and (Post)Modernist Culture

4.101: postmodern and 21st century literature in america, postmodernity/postmodernism.

Our current period in history has been called by many the postmodern age (or “postmodernity”) and many contemporary critics are understandably interested in making sense of the time in which they live. Although an admirable endeavor, such critics inevitably run into difficulties given the sheer complexity of living in history: we do not yet know which elements in our culture will win out and we do not always recognize the subtle but insistent ways that changes in our society affect our ways of thinking and being in the world. One symptom of the present’s complexity is just how divided critics are on the question of postmodern culture, with a number of critics celebrating our liberation and a number of others lamenting our enslavement….

One of the problems in dealing with postmodernism is in distinguishing it from modernism. In many ways, postmodern artists and theorists continue the sorts of experimentation that we can also find in modernist works, including the use of self-consciousness, parody, irony, fragmentation, generic mixing, ambiguity, simultaneity, and the breakdown between high and low forms of expression. In this way, postmodern artistic forms can be seen as an extension of modernist experimentation; however, others prefer to represent the move into postmodernism as a more radical break, one that is a result of new ways of representing the world including television, film (especially after the introduction of color and sound), and the computer. Many date postmodernity from the sixties when we witnessed the rise of postmodern architecture; however, some critics prefer to see WWII as the radical break from modernity, since the horrors of Nazism (and of other modernist revolutions like communism and Maoism) were made evident at this time. The very term “postmodern” was, in fact, coined in the forties by the historian, Arnold Toynbee. ( Click this link for more about the aforementioned aspects of postmodernism.)

Postmodernist Literature

Postmodernism is difficult to define. Don DeLillo is recognized as one of America’s premier postmodernist novelists, yet he rejects the term entirely. “If I had to classify myself,” he explains in a 2010 interview in the Saint Louis Beacon , “it would be in the long line of modernists, from James Joyce through William Faulkner and so on. That has always been my model.”

DeLillo in New York City, 2011

Literally, the term postmodernism refers to culture that comes after Modernism, referring specifically to works of art created in the decades following the 1950s. The term’s most precise definition comes from architecture, where it refers to a contemporary style of building that rejects the austerity and minimalism of modernist architecture’s glass boxes and towers; postmodernist architects retain the functionalist core of the modernist building but then decorate their boxes and towers with playful colors, forms, and ornaments that reference disparate historical eras. Indeed, play with media and materials, and with forms, styles, and content is one of the chief characteristics of postmodernist art.

While postmodernist architects play with the material of their buildings, postmodernist writers play with the material that their poems and stories are made of, namely language and the book. Postmodernist writers freely use all the challenging experimental literary techniques developed by the modernists earlier in the twentieth century as well as new, even more experimental techniques of their own invention. In fiction, many postmodernist authors adopt the self-referential style of “ metafiction ,” a story that is just as much about the process of telling a story as it is about describing characters and events. Donald Barthelme’s postmodernist short story, “The School,” contains metafictional elements that comment on the process of storytelling and meaning-making, as when the narrator describes how the “lesson plan called for tropical fish input” even though all the students in the schoolroom knew the fish would soon die. Who is telling this story? Bartheleme? The unnamed narrator? The lesson plan? The stories that make up history itself are often a playground for postmodernist authors, as they take material found in history books and weave it into new tales that reveal secret histories and dimly perceived conspiracies. David Foster Wallace’s essay, “Consider the Lobster,” is a good example of the narrative excess found in postmodern literature. In this essay written for Gourmet magazine, Wallace uses his visit to the Maine Lobster Festival to tell a history of the lobster since the Jurassic period that eventually turns against the organizers of the festival themselves, who may or may not be covering up the truth about how much lobsters suffer in their cooking pots. The form of the essay cannot even contain Wallace’s ideas, which spill over into twenty excessively long footnotes, many of which are little essays in themselves. In addition to playing with the form of literature and the notion of authorship, postmodernist writers also often play with popular sub-genres such as the detective story, horror, and science fiction. For example, in her poem “Diving into the Wreck,” Adrienne Rich evokes both the detective story and science fiction as she imagines a futuristic diver visiting a deep sea wreck in order to solve the mystery of why literature and history have been mostly about men and not women.

Not all works of postmodernist literature are stylistically experimental or playful. Rather, their authors explore the meaning and value of postmodernity as a cultural condition. Several philosophers and literary critics many of whose names have become synonymous with postmodernism itself have helped us understand what the postmodern condition may be. “Poststructuralist” philosophers such as Jacques Derrida and Jean Baudrillard have argued that words and texts do not reflect the world but instead exist as their own self-referential systems, containing and even creating the world they describe. When we perceive the world, Derrida’s philosophy of “deconstruction” claims, we see not things but “signs” that can be understood only through their relation to other signs. “There is no outside the text,” Derrida famously claimed in his book Of Grammatology (1967). In this way, words and books and texts are powerful things, for in them our world itself is created an insight that many postmodernist creative writers share. Baudrillard, in turn, argues in his book, Simulacra and Simulation (1981), that the real world has been filled up with and even replaced by simulations that we now treat as reality: simulacra. These postmodern sensibilities are reflected in both Allen Ginsberg’s poem, “A Supermarket in California,” and our selection from DeLillo’s White Noise . In Ginsberg’s poem, food has become “brilliant stacks of cans” knowable only by their similarity to each other. The “neon fruit supermarket” is not even a simulation of a real farm but instead is a simulacra full of families who have probably never even seen a farm. In DeLillo’s novel, we find the insight that the collected photographs of “the most photographed barn in America” are more real than the physical barn being photographed. Nobody knows why this particular barn is the most photographed barn in America. The barn is famous simply because it is a much-copied text, valued more as a sign in relation to other signs (all those photos of the same thing) than as a thing in itself with a specific history and a particular use. In his book Postmodernism (1991), the leftist critic Frederic Jameson chastises postmodernism for being the “cultural logic of late capitalism,” which for him is a culture that erases the real meanings and relations of things such as the most photographed barn in America, replacing true history with nostalgic simulacra.

Read this excerpt about “the most photographed barn in America” from DeLillo’s White Noise (1985):

Several days later Murray asked me about a tourist attraction known as the most photographed barn in America. We drove 22 miles into the country around Farmington. There were meadows and apple orchards. White fences trailed through the rolling fields. Soon the sign started appearing. THE MOST PHOTOGRAPHED BARN IN AMERICA. We counted five signs before we reached the site. There were 40 cars and a tour bus in the makeshift lot. We walked along a cowpath to the slightly elevated spot set aside for viewing and photographing. All the people had cameras; some had tripods, telephoto lenses, filter kits. A man in a booth sold postcards and slides — pictures of the barn taken from the elevated spot. We stood near a grove of trees and watched the photographers. Murray maintained a prolonged silence, occasionally scrawling some notes in a little book.

“No one sees the barn,” he said finally.

A long silence followed.

“Once you’ve seen the signs about the barn, it becomes impossible to see the barn.”

He fell silent once more. People with cameras left the elevated site, replaced by others.

“We’re not here to capture an image, we’re here to maintain one. Every photograph reinforces the aura. Can you feel it, Jack? An accumulation of nameless energies.”

There was an extended silence. The man in the booth sold postcards and slides.

“Being here is a kind of spiritual surrender. We see only what the others see. The thousands who were here in the past, those who will come in the future. We’ve agreed to be part of a collective perception. It literally colors our vision. A religious experience in a way, like all tourism.”

Another silence ensued.

“They are taking pictures of taking pictures,” he said.

He did not speak for a while. We listened to the incessant clicking of shutter release buttons, the rustling crank of levers that advanced the film.

“What was the barn like before it was photographed?” he said. “What did it look like, how was it different from the other barns, how was it similar to other barns?”

The culture of postmodernism in general exhibits a skepticism towards the grand truth claims and unifying narratives that have organized culture since the time of the Enlightenment. In postmodern culture, history becomes a field of competing histories and the self becomes a hybrid being with multiple, partial identities. In his provocative study, The Postmodern Condition (1979), the philosopher Jean Francois Lyotard argues that what defines the present postmodern historical era is the collapse of “grand narratives” that explain all experience, faiths, and truths, such as those found in science, politics, and religion; in place of all-explaining master narratives, he argues, we now know the world through smaller micro-narratives that don’t all fit together into a greater coherent whole.

These insights are thoroughly explored in the confessional, feminist, and multicultural American literature of this era, whose authors write from their subjective points of view rather than presuming to represent the sum total of all American experiences, and whose works show us that American history has been far from the same experience for all Americans. For example, both Sylvia Plath and Theodore Roethke have poems about their fathers, but their appreciation of their respective fathers is shaped by both their genders and their own personal histories. Roethke feels a kinship with his father. Plath, however, sees her father as an enemy. The Native American author Leslie Marmon Silko tells her story specifically from the point of view of a member of the Laguna Pueblo tribe, whose members use old stories about the Yellow Woman and the ka’tsina spirit to understand their tribe’s relationship to the rest of America. In the works of African-American literature in this section, we find similar explorations of cultural identity.

Read these excerpts from Almanac of the Dead (1991) by Leslie Marmon Silko:

James Baldwin uses the African-American music of the blues and jazz to describe the relationship between the two brothers in his story, “Sonny’s Blues.” Ralph Ellison, in the first chapter from his novel Invisible Man (1952), writes about the experience of attending a segregated school that keeps black Americans separate from white Americans. Toni Morrison and Alice Walker, in their stories, explore the hybrid nature of African-American identity itself, showing us the tensions that arise when one’s identity is both American and black.

The varied, playful, experimental literature of postmodernism, the critic Brian McHale helpfully observes in his book Constructing Postmodernism (1993), presents readers not with many ways to know our one world but instead with many knowable worlds created within many disparate works in many different ways. Modernist authors all strove to devise new techniques with which to accurately represent the world, McHale observes. Postmodernist authors, however, are no longer concerned with representing one knowable world but instead with creating many literary worlds that represent a diversity of experiences. Thus, much as the American literature of the contemporary era presents us with a record of how the nation has known, questioned, and even redefined itself, so too does the literature of postmodernism present us with a record of how writers have known, questioned, and even redefined what literature is.

Literature in the 21st Century

In many ways, the literature of this century is still postmodern, as it challenges grand narratives, monolithic constructions of identity, and many traditions and techniques of literature of the past. (And if it is not, there is no term for what is post-postmodern!) One motif that has persisted and proliferated during this century revolves around the impact of technology on the topics postmodern writers addressed in the latter part of the 21st century. Cyberpunk , which dealt with the “down and out” struggling to survive or transform a dystopian setting in which technology both empowers and enslaves, and which rose to prominence in the 1980s with authors such as William Gibson, Pat Cadagin, and Bruce Sterling, set the groundwork for this genre.

William Gibson at a 2007 reading from his new book Spook Country at Bolen Books in Victoria BC Canada.

Fiction writers such as Alaya Dawn Johnson continue to question essentializing of sexual identity and practice, and a patriarchal, if not-so-dystopian society in a work such as The Summer Prince . Larissa Lai considers the same kind of topics with the integration and, at times, through the lens of Chinese mythology. The Circle by David Eggers confronts the loss of privacy and authentic selfhood via technology, and the question of if progress or self-definition is more important in an ever speeding up world. And M.T. Anderson’s Feed calls into question the supposed utopia of a world proming instant gratification at the expense of destroying the environment, dumbing down the citizenry, and a general loss of humanity.

Johnson in 2013

In drama Jennifer Haley has written plays suggesting there today exists a blurring of the material and digital in relation to video games ( Neighborhood 3: Requisition of Doom ) and virtual reality ( The Nether ). And Jordan Harrison’s play Marjorie Prime addresses the possibilities and limitations of technology for filling the gap of losing a loved one and preserving one’s “existence” after death.

What this era is and will be known as is still unclear, and the dominance of visual and aural narrative forms is likely pushing the written narrative to a less pervasive and influential role than anytime before the emergence of the alphabet. But, then again, what constitutes literature is also changing with the times, as everything from video games to websites have been analyzed as forms of literature this century. So, maybe this is a transformational time for literature and we will just have to wait to see how the changes play out.

- Postmodernism. Authored by : Amy Berke, et al.. Provided by : LibreTexts. Located at : https://human.libretexts.org/Bookshelves/Literature_and_Literacy/Book%3A_Writing_the_Nation_-_A_Concise_Introduction_to_American_Literature_1865_to_Present_(Berke%2C_Bleil_and_Cofer)/06%3A_American_Literature_Since_1945_(1945_-_Present)/6.06%3A_Postmodernism . License : CC BY-NC-SA: Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike

- Authored by : Thousand Robots. Provided by : Wikimedia Commons. Located at : https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Don_DeLillo#/media/File:Don_delillo_nyc_02-cropped.jpg . License : CC BY: Attribution

- Uncle Gibby. Authored by : Dylan Parker . Provided by : Wikimedia Commons. Located at : https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/William_Gibson#/media/File:Uncle_Gibby.jpg . License : CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Johnson in 2013. Authored by : Luigi Novi. Provided by : Wikimedia Commons. Located at : https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Alaya_Dawn_Johnson#/media/File:6.30.13AlayaJohnsonByLuigiNovi1.jpg . License : CC BY: Attribution

- General Introduction to the Postmodern. Authored by : Dino Franco Felluga. Provided by : Purdue University. Located at : https://cla.purdue.edu/academic/english/theory/postmodernism/modules/introduction.html . License : Public Domain: No Known Copyright

- The Most Photographed Barn in America Exerpts from White Noise by Don DeLillo. Authored by : Benjamin Mako Hill. Provided by : WordPress. Located at : https://mako.cc/copyrighteous/extra/most_photographed_barn_in_america.html . License : CC0: No Rights Reserved

- Contending Worldviews in Leslie Marmon Silko's Almanac of the Dead. Authored by : Theresa Delgadillo. Provided by : WordPress. Located at : https://library.osu.edu/site/mujerestalk/2014/08/12/contending-worldviews-in-leslie-marmon-silkos-almanac-of-the-dead/ . License : CC0: No Rights Reserved

- Literature in the 21st Century and Conclusion. Authored by : Steven Hymowech. Provided by : Lumen Learning. Located at : https://courses.lumenlearning.com/suny-fmcc-hum140/chapter/4-101-postmodern-literature/ . License : Public Domain: No Known Copyright

- New Media for Art. Provided by : Lumen Learning. Located at : https://courses.lumenlearning.com/boundless-arthistory/chapter/new-media-for-art/ . License : CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

Privacy Policy

- Search Menu

Sign in through your institution

- Browse content in Arts and Humanities

- Browse content in Architecture

- History of Architecture

- Browse content in Art

- History of Art

- Browse content in Classical Studies

- Classical Literature

- Religion in the Ancient World

- Browse content in History

- Colonialism and Imperialism

- Diplomatic History

- Environmental History

- Genocide and Ethnic Cleansing

- Historical Geography

- History by Period

- History of Agriculture

- History of Gender and Sexuality

- Industrial History

- Intellectual History

- International History

- Legal and Constitutional History

- Local and Family History

- Maritime History

- Military History

- Political History

- Regional and National History

- Revolutions and Rebellions

- Slavery and Abolition of Slavery

- Social and Cultural History

- Theory, Methods, and Historiography

- Urban History

- World History

- Linguistics

- Browse content in Literature

- Literary Studies (European)

- Literary Studies (Romanticism)

- Literary Studies (American)

- Literary Studies - World

- Literary Studies (1500 to 1800)

- Literary Studies (19th Century)

- Literary Studies (20th Century onwards)

- Literary Studies (British and Irish)

- Literary Studies (Early and Medieval)

- Literary Studies (Fiction, Novelists, and Prose Writers)

- Literary Studies (Plays and Playwrights)

- Literary Studies (Poetry and Poets)

- Literary Studies (Postcolonial Literature)

- Literary Studies (Queer Studies)

- Literary Studies (War Literature)

- Literary Studies (Women's Writing)

- Literary Theory and Cultural Studies

- Shakespeare Studies and Criticism

- Media Studies

- Browse content in Music

- Applied Music

- Ethnomusicology

- Music Cultures

- Music and Media

- Music Theory and Analysis

- Musical Scores, Lyrics, and Libretti

- Musical Structures, Styles, and Techniques

- Musicology and Music History

- Performance Practice and Studies

- Race and Ethnicity in Music

- Browse content in Performing Arts

- Browse content in Philosophy

- Aesthetics and Philosophy of Art

- Epistemology

- History of Western Philosophy

- Metaphysics

- Moral Philosophy

- Philosophy of Science

- Philosophy of Language

- Philosophy of Mind

- Philosophy of Law

- Philosophy of Religion

- Philosophy of Mathematics and Logic

- Social and Political Philosophy

- Browse content in Religion

- Biblical Studies

- Christianity

- History of Religion

- Judaism and Jewish Studies

- Qumran Studies

- Religion and Politics

- Religion and Art, Literature, and Music

- Religious Studies

- Browse content in Society and Culture

- Cultural Studies

- Technology and Society

- Browse content in Law

- Company and Commercial Law

- Browse content in Comparative Law

- Systems of Law

- Browse content in Constitutional and Administrative Law

- Government Powers

- Local Government Law

- Criminal Law

- Employment and Labour Law

- Environment and Energy Law

- History of Law

- Human Rights and Immigration

- Intellectual Property Law

- Browse content in International Law

- Public International Law

- Jurisprudence and Philosophy of Law

- Law and Politics

- Law and Society

- Browse content in Legal System and Practice

- Legal Skills and Practice

- Medical and Healthcare Law

- Browse content in Policing

- Police Regional Planning

- Property Law

- Browse content in Medicine and Health

- History of Medicine

- Browse content in Public Health and Epidemiology

- Public Health

- Browse content in Science and Mathematics

- Browse content in Biological Sciences

- Microbiology

- Zoology and Animal Sciences

- Browse content in Earth Sciences and Geography

- Palaeontology

- Environmental Science

- History of Science and Technology

- Browse content in Psychology

- Clinical Psychology

- Cognitive Psychology

- Developmental Psychology

- Evolutionary Psychology

- Health Psychology

- Social Psychology

- Browse content in Social Sciences

- Browse content in Anthropology

- Theory and Practice of Anthropology

- Browse content in Business and Management

- Business Ethics

- Business History

- Corporate Social Responsibility

- Criminology and Criminal Justice

- Browse content in Economics

- Agricultural, Environmental, and Natural Resource Economics

- Econometrics and Mathematical Economics

- Economic Systems

- Economic History

- Economic Development and Growth

- Financial Markets

- History of Economic Thought

- International Economics

- Labour and Demographic Economics

- Macroeconomics and Monetary Economics

- Microeconomics

- Public Economics

- Urban, Rural, and Regional Economics

- Browse content in Environment

- Climate Change

- Conservation of the Environment (Social Science)

- Social Impact of Environmental Issues (Social Science)

- Browse content in Politics

- African Politics

- Comparative Politics

- Conflict Politics

- Environmental Politics

- International Relations

- Middle Eastern Politics

- Political Economy

- Political Theory

- Politics and Law

- Public Policy

- Russian Politics

- UK Politics

- US Politics

- Browse content in Regional and Area Studies

- African Studies

- Asian Studies

- Native American Studies

- Browse content in Sociology

- Childhood Studies

- Economic Sociology

- Health, Illness, and Medicine

- Migration Studies

- Organizations

- Race and Ethnicity

- Social Theory

- Social Stratification, Inequality, and Mobility

- Sociology of Religion

- Sociology of Education

- Urban and Rural Studies

- Reviews and Awards

- Journals on Oxford Academic

- Books on Oxford Academic

- < Previous chapter

- Next chapter >

2 The Value of Literature

- Published: November 2004

- Cite Icon Cite

- Permissions Icon Permissions

This chapter first looks at the value and definition of art as it should and can be if ever it has moral value. The chapter asks the question why and how are artistic and literary activity morally valuable and excellent? For this question to merit an answer, two issues are addressed in the chapter. The first issue is the relationship of beauty to truth and goodness. In what ways are they compatible? The second issue deals with the uniqueness of beauty and in what ways is it different from the true and the good. For example, In the Republic , Plato speaks of the artist as an imitator twice removed from reality. In that sense, what we today call reality may have implications of deception in such a way that it blocks us from understanding a more essential meaning, a more genuine reality. This initiates the chapter's search for the truth and goodness of literature and literary criticism.

Personal account

- Sign in with email/username & password

- Get email alerts

- Save searches

- Purchase content

- Activate your purchase/trial code

- Add your ORCID iD

Institutional access

Sign in with a library card.

- Sign in with username/password

- Recommend to your librarian

- Institutional account management

- Get help with access

Access to content on Oxford Academic is often provided through institutional subscriptions and purchases. If you are a member of an institution with an active account, you may be able to access content in one of the following ways:

IP based access

Typically, access is provided across an institutional network to a range of IP addresses. This authentication occurs automatically, and it is not possible to sign out of an IP authenticated account.

Choose this option to get remote access when outside your institution. Shibboleth/Open Athens technology is used to provide single sign-on between your institution’s website and Oxford Academic.

- Click Sign in through your institution.

- Select your institution from the list provided, which will take you to your institution's website to sign in.

- When on the institution site, please use the credentials provided by your institution. Do not use an Oxford Academic personal account.

- Following successful sign in, you will be returned to Oxford Academic.

If your institution is not listed or you cannot sign in to your institution’s website, please contact your librarian or administrator.

Enter your library card number to sign in. If you cannot sign in, please contact your librarian.

Society Members

Society member access to a journal is achieved in one of the following ways:

Sign in through society site

Many societies offer single sign-on between the society website and Oxford Academic. If you see ‘Sign in through society site’ in the sign in pane within a journal:

- Click Sign in through society site.

- When on the society site, please use the credentials provided by that society. Do not use an Oxford Academic personal account.

If you do not have a society account or have forgotten your username or password, please contact your society.

Sign in using a personal account

Some societies use Oxford Academic personal accounts to provide access to their members. See below.

A personal account can be used to get email alerts, save searches, purchase content, and activate subscriptions.

Some societies use Oxford Academic personal accounts to provide access to their members.

Viewing your signed in accounts

Click the account icon in the top right to:

- View your signed in personal account and access account management features.

- View the institutional accounts that are providing access.

Signed in but can't access content

Oxford Academic is home to a wide variety of products. The institutional subscription may not cover the content that you are trying to access. If you believe you should have access to that content, please contact your librarian.

For librarians and administrators, your personal account also provides access to institutional account management. Here you will find options to view and activate subscriptions, manage institutional settings and access options, access usage statistics, and more.

Our books are available by subscription or purchase to libraries and institutions.

| Month: | Total Views: |

|---|---|

| October 2022 | 1 |

| October 2023 | 2 |

| April 2024 | 1 |

- About Oxford Academic

- Publish journals with us

- University press partners

- What we publish

- New features

- Open access

- Rights and permissions

- Accessibility

- Advertising

- Media enquiries

- Oxford University Press

- Oxford Languages

- University of Oxford

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University's objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide

- Copyright © 2024 Oxford University Press

- Cookie settings

- Cookie policy

- Privacy policy

- Legal notice

This Feature Is Available To Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account

This PDF is available to Subscribers Only

For full access to this pdf, sign in to an existing account, or purchase an annual subscription.

- Submissions

- Author Guidelines

- Research Integrity

- Publication Ethics Statement

- Competing Interests

- Ensuring a Blind Review

C21 Literature Special Issue: The Century at 25

An exit out of the 'hive': post-apocalyptic fictions of data capitalism and technological acceleration.

Rebecca Bevington (University of York)

Linda Grant's Dys-Chrony: Interwoven Temporalities in A Stranger City (2019)

Ulla Rahbek (University of Copenhagen)

The Body that Writes: Gender, Class and the Abject Female Body in Hannah Kent’s Burial Rites (2013)

Kiriaki Massoura (Northumbria University)

Ways of Looking: The Composite Novel and Posthuman Community in Jon McGregor's Reservoir 13

Adele Guyton (KU Leuven)

The Writing of Ruins: Beckett, Late Modernism, and the Inhuman in Don DeLillo’s Postmillennial Fiction

Marc Farrant (University of Amsterdam)

Spreading the Word: What Fifty Shades of Grey Means for World Literature

Waiyee Loh (Kanagawa University)

#MeToo and the Northern Ireland Troubles: Anna Burns' Milkman

Matt McGuire (Western Sydney University)

C21 Literature: Journal of 21st-century Writings is the journal of the British Association for Contemporary Literary Studies (BACLS). The journal is dedicated to examining the genres, forms of publication, and circulation of 21st-century writings. C21 Literature is a logical development of the explosion of interest in 21st-century writings, seen in book groups, university courses, and the development of online publishing.

Volume 11 • Issue 1 • 2024 • Spring 2024

Rebecca Bevington

2024-01-17 Volume 11 • Issue 1 • 2024 • Spring 2024

Migration and the Dystopian Imagination of European Border Regimes

2024-02-28 Volume 11 • Issue 1 • 2024 • Spring 2024

Jennifer Cooke, Contemporary Feminist Life-Writing: The New Audacity (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2020), 234 pages, £83.99 (hardback)

Ines Garcia

2024-05-07 Volume 11 • Issue 1 • 2024 • Spring 2024

Kristian Shaw, Brexlit: British Literature and the European Project. Bloomsbury Academic, 2021.

Wiktoria Maria Tunska

Posted by Dr Caroline Edwards on 2024-01-18

The twenty-first century is nearly a quarter done. The contemporary – that category which has so often been theorised, following Barthes and Agamben, as fundamentally out of step with its own time – is starting to synchronise its watch with the temporal bounds of the current century. Despite a flurry of critical efforts to name, characterise, and categorise the paradigm shifts of the present in [...]

Posted by Siân Adiseshiah on 2022-09-16

We are pleased to announce that C21 is advertising for two positions: 1) a Deputy Editor and 2) a Reviews Editor. Both these roles require some prior experience of editorial work, peer review, or academic writing and communications. C21 already has two Deputy Editors but is creating an opening for a third to share the workload so each role is not too onerous. An opening [...]

Posted by Dr Caroline Edwards on 2022-07-07

We're delighted to announce the re-launch of C21!After ten years of managing the journal, Professor Katy Shaw is standing down as Editor-in-Chief. The British Association of Contemporary Literary Studies has appointed two new Editors-in-Chief: Dr Siân Adiseshiah (Loughborough University) and Dr Caroline Edwards (Birkbeck, University of London). They join the current team of Deputy Editors, [...]

Posted by Katy Shaw on 2021-02-02

C21 Literature is seeking NEW article submissions for 2021.Please read the journal submission guidelines and the scope of the journal pages on this site, or take a look at our database of previous publications before submitting. If you have any questions relating to a future submission, please email our Editor: Professor Katy Shaw [email protected] also welcome expressions of [...]

Posted by Katy Shaw on 2020-12-10

Essential? Different? Exceptional? The Book Trade and Covid-19by Professor Claire Squires, University of Stirling, UKFor many - probably all readers on this platform - a book is an essential Christmas gift to give or receive. Those rectangular objects, so bibliographically obvious nestled in their wrapping paper under the Christmas tree, also form delightful seasonal and familial [...]

Literature in the 21st Century

Coordinators.

Prof. dr. Ellen Rutten, Dr. Arent van Nieukerken, Dr. Eric Metz

Members of the research group

Carrol Clarkson, Yra van Dijk, Shelley Godsland, Christ-Maria Lerm Hayes, Eric Metz, Divya Nadkarni, Arent van Nieukerken, Esther Peeren, Suze van der Poll, Ellen Rutten, Jenny Stelleman, Thomas Vaessens, Philip Westbroek.

Description of the research programme of the research group

The research group ‘Literary Studies in the 21 st Century’ focuses on the description, categorization and analysis of various types of “literariness” that have developed just before and after 2000. Hitherto, academic research of 21 st -century literature has largely focused on grasping general cultural processes: literary texts have usually – and fruitfully – been employed as illustrating the rhythms of cultural change. Much less attention has been devoted to the development and/or evolvement of various types of “literariness” as a specific feature of these general processes. However, the relationship between individual literary phenomena (poems, novels, plays, essays) and the realm of cultural narrations is essentially mediated by a “middle ground” of literary conventions, such as generic conventions, narrative structures, stylistic devices etc. The relative neglect of this field of studies in the discourse of cultural studies – a discourse that not seldomly overlooks the categories elaborated by twentieth- century (post-)structuralist narratology and poetics – has led to many misrepresentations, not only of the immanent development of various local literary traditions, but also of their transnational and transregional interaction. Our research group aims to correct one-sidedness by exploring “multivoiced” ( à la Bakhtin) representations of literariness as a major branch of cultural transformation in the new millennium.

The research questions that the group will critically address include the following two:

- How do 21 st -century authors relate to trans-Atlantic postmodernism in its different phases? In answering this question we explore the interaction between both positive views of postmodernism (as a universal model of cultural “progress” and “emancipation) and negative interpretations (of postmodernism as boasting a “disintegrating” impact that, e.g., home-grown literary traditions can combat)?

- How do contemporary literary authors engage with previous phases of cultural narrations? Relevant examples of engagement with existing paradigms include the wish to return to “Christian European culture” or different forms of “positivist” anti- relativism.