- Request Info

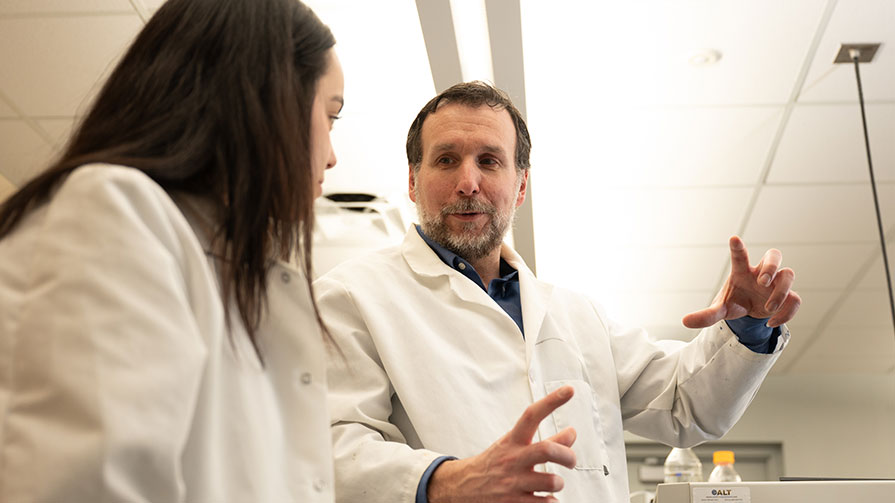

"Incredible achievement and great tragedy unfolded on the treacherous slopes of Mount Everest in the spring of 1996," begins Trustee Professor of Management Michael Roberto ’s landmark 2003 case study Mount Everest–1996 . Recently named a “Classic Case” by The Case Centre, a nonprofit dedicated to furthering business education and the case study method, it documents the harrowing story of an ill-fated attempt to summit one of the world’s tallest mountains led by some of the world’s top climbers.

Mount Everest–1996 also exemplifies Roberto’s commitment to using immersive, real-world examples to educate the next generation of leaders. A good case study serves a springboard for discussion and introspection as well as an informational resource, he explains. “The case method is about putting a student in the shoes of a decision maker. It’s not about the professor coming in and preaching and teaching a bunch of theory through a lecture, but instead giving the students a messy, real world situation.”

The story of Everest Roberto speaks from experience. When The Case Centre compiled a 2017 list of the 40 best-selling case study authors in the world, he ranked #25. His award-winning case studies range from an examination of the rise of Planet Fitness to a multimedia analysis of the 2003 Columbia space shuttle accident.

“Everest always captures the imagination. If you want students to learn, you've got to motivate them and one way you do that is to use really compelling settings.”

Mount Everest–1996 is the case study for which Roberto is perhaps best known. It explores a March 1996 tragedy in which five mountaineers from two widely-respected teams, including the teams’ two leaders, Rob Hall and Scott Fischer, perished while attempting to summit Mount Everest during an especially deadly season. Roberto’s examination of the disaster has been used in graduate and undergraduate courses around the world and he has been invited to personally teach the case at institutions ranging from Fortune 500 companies to West Point and the Naval War College to the Federal Bureau of Investigation.

Fascinated by Into Thin Air , an account written by expedition survivor Jon Krakauer, Roberto realized the story could be used to teach students about high-stakes decision-making. He exhaustively researched and worked on the case for more than a year, including learning about mountaineering and studying accounts from the surviving climbers.

Total immersion The resulting case study recounts the events and decisions that led to the disaster, from issues involving logistics and inter-personal conflicts to larger questions of leadership under stress conditions. It’s a perfect starting point for students to explore a range of key topics including team dynamics, evaluating risk, and knowing when to cut losses.

“A great case has to have some element or points to debate, some level of tension, and some level of uncertainty.”

The subject matter, Roberto notes, draws students in and gets them thinking. “Everest always captures the imagination,” he says. “If you want students to learn, you've got to motivate them and one way you do that is to use really compelling settings.”

But even though the story is extraordinary, the lessons it offers are universal, Roberto asserts. “I think one of the reasons the case study has been so compelling is because, while we haven't all been in a life-or-death situation like that, we've all been in teams that broke down in similar ways or we’ve been in situations where we've thrown good money after bad – whether it's a home improvement project or a used car or a business project,” he states. “I think the case touches on some essentials of human nature and group behavior that are very fundamental.”

Learning from failure Part of the success of Mount Everest–1996 can be attributed to its approach. In developing the case study as a member of the Harvard Business Faculty, Roberto decided to take a different tack than the others he was seeing. “When I looked around, it seemed that 99% of the case studies that students were studying were success stories,” Roberto remembers. “I wanted to write about a failure.”

In studying failure, students aren’t presented with a clear-cut path to follow or a list of instructions to memorize and replicate. Instead, they are required to do their own analysis and consider what they might do in a similar situation. “If there's a clear right answer, that's a bad case,” Roberto explains. “A great case has to have some element or points to debate, some level of tension, and some level of uncertainty.”

“I have students I had 20 years ago who still remember this case.”

That sort of ambiguity lies at the heart of Mount Everest–1996 . “So much of what is written about Everest expeditions and those kinds of things is about the heroic person who gets to the top,” says Roberto. “This is about being able to look and say, ‘Yes, these qualities are needed to do great, ambitious, remarkable things, but, in a way, some of those same qualities can also get you in trouble.”

A lasting impact The Everest tragedy’s inherent humanity is one of the qualities that has made it so resonant for students, Roberto believes. “I don't look at Hall and Fischer and say, ‘Oh they're terrible leaders.’ I look at the case and say, ‘But for the grace of God, go I,’” he states. “The mistakes they made were very human. I don't teach it as they're bad people or bad leaders so much as they made some bad choices for some of the same reasons we all make bad choices.”

For nearly two decades, students studying Mount Everest–1996 have learned from those choices and take away lessons they’ve used to go out into the world and lead their own teams. The time they spend with the case study, Roberto says, tends to stick with them. “They never forget it,” he says. “I have students I had 20 years ago who still remember this case.”

Related Stories

June 27, 2024

June 20, 2024

June 17, 2024

June 13, 2024

June 11, 2024

- Starting a Business

- Growing a Business

- Small Business Guide

- Business News

- Science & Technology

- Money & Finance

- For Subscribers

- Write for Entrepreneur

- Tips White Papers

- Entrepreneur Store

- United States

- Asia Pacific

- Middle East

- South Africa

Copyright © 2024 Entrepreneur Media, LLC All rights reserved. Entrepreneur® and its related marks are registered trademarks of Entrepreneur Media LLC

What the 1996 Everest Disaster Teaches About Leadership When leaders fall prey to analytical bias and unexamined assumptions, the consequences can be very bad.

By Murray Newlands Edited by Dan Bova Oct 6, 2016

Opinions expressed by Entrepreneur contributors are their own.

Leading a team requires more than just an ability to make decisions. To be a strong leader, you need to possess an awareness of how people tick. What is your team capable of, and what problematic behavior are they enacting? More importantly, do you know when your decision-making and leadership abilities might be compromised, so you can head catastrophe off at the pass?

Michael A. Roberto's article, Lessons From Everest , illuminates some essential lessons on leadership, drawing on psychology from the 1996 Everest disaster. During an attempt to summit Everest in 1996 -- immortalized in Jon Krakauer's book Into Thin Air -- a powerful storm swept the mountain, obscuring visibility for the 23 climbers on return to base camp. Five people died on the mountain that day, the most disastrous tragedy on Everest until an earthquake-caused avalanche in 2014.

Of course, there are many conflicting ideas as to what may have contributed to such an unprecedented disaster, and the argument stands that the climbers were well aware of the inherent danger of climbing Everest.

But Roberto's article calls into account the decision-making abilities of experienced trek leaders Rob Hall and Scott Fischer. Drawing from behavioral decision-making, Roberto concludes that the two leaders were operating under some common cognitive biases that likely contributed to the Everest disaster.

Related: The Responsibility of a True Leader Is to Be a Great Coach

These common and predictable cognitive biases impair judgement and the choices that people make and are especially disastrous in leaders. I've condensed some common cognitive biases that Roberto found in action on Everest. If you want to be a truly powerful leader, take them time to learn more about your decision-making -- you may even recognize a few of these biases in yourself.

The sunk-cost effect.

People who are operating under the sunk-cost effect tend to double down on their commitment to a course of action in which they have invested considerable resources, like time, money or effort. The sunk cost effect causes normally rational people to throw away common sense, allowing past investment decisions to effect their future choices, "despite seeing consistently poor results," writes Roberto, escalating what could have been non-situation.

All three of these resources -- time, money and effort -- had been spent on Everest. The trek cost more than $70,000. Each climber had spent years training and preparing, and the final push to the summit was over 18 hours long, following weeks of difficulty acclimating and hiking to base camp. The final push to the summit was incredibly dangerous and required perfect timing so auxiliary oxygen bottles would last and climbers would not get caught in darkness on their return to camp. Hall and Fischer "knew that individuals would find it difficult to turn around after coming so far and expending such an effort," and past Everest guides even reported climbers laughing in their face when told that they would not be able to summit.

Hall and Fischer, despite mentioning numerous times that climbers would be turned around if they could not make the summit by 1:00 pm or 2:00 pm at the very latest, did not turn the climbers around. None of the 23 climbers made it to the summit by 1:00 pm, and only six climbers made it by 2:00 pm. Roberto writes: "Doug Hansen, a climber on Hall's team, expressed this very sentiment during his final descent: "I've put too much of myself into this mountain to quit now without giving it everything I've got.' Hansen had [previously] climbed the mountain with Hall's expedition in 1995, and Hall had turned him around just 330 vertical feet from the summit."

Related: 10 Signs That You Suck As a Leader

Unfortunately, Hansen did give the mountain everything he had. He did not reach the summit until after 4:00 pm, and he perished on his way back to base camp. Hansen's thinking was clouded by the sunk-cost effect, and he paid with his life. Other climbers experienced severe blindness and sickness, yet still pressed on.

The sunk cost effect can be incredibly motivating to those people who should have, and otherwise would have, changed course to a more logical path -- experts and novices alike. As a leader, your awareness of this cognitive bias is necessary to save you and your team from massive failures and even tragedies.

Overconfidence bias.

According to Roberto, most leaders experience an overconfidence bias in such widely varying fields as medicine, engineering, academia and business. Overconfidence is fairly normal among high-achieving individuals because possessing strong confidence is necessary to reach such heights of success and expertise. The remarkable achievements of starting and running a multi-million dollar business, or planning and executing one of the most difficult climbs on the planet, requires more confidence than most possess.

However, that same overconfidence can circle back around to create distressing problems. Hall had made the summit of Everest four times and led more than 39 people to the summit, leading him to believe that he could not fail. In fact, Hall is recorded by Krakauer expressing his belief that some future team would experience disaster on Everest, but did not believe that disaster would befall his team. He was only worried that his team would be the one called on to rescue the hypothetical struggling team. Hall's overconfidence blinded him. He couldn't see that he could be the one who failed.

Successful leaders often have an overabundance of confidence, so this cognitive bias is essential to understand. While confidence is crucial for any leader, this should not preclude preparing for possible failures in a comprehensive way. You should never be caught off guard.

Recency effect.

The recency effect is a cognitive bias that leads decision makers to rely very heavily on the most readily available information and evidence, particularly information that appeared most recently. Instead of looking for all possible sources of information and weighing them equally, the recency effect bias leads people to believe -- wrongly -- that recently presented evidence is good enough and will hold. Roberto gives the example of a study where chemical engineers misdiagnosed a product failure "because they tended to rely too heavily on causes that they had experienced recently."

This critical error played out on Everest in Hall and Fischer's incorrect assumption that the weather would be calm and agreeable. They both led expeditions on Everest for several previous seasons that experienced only agreeable weather, however, this was the outlier, not the norm. For many seasons prior to Hall and Fischer's expeditions, storms were the norm. In fact, there were three consecutive years in the mid-eighties where no one made the summit due to terrible winds. Both guides failed to look at past weather patterns and did not realize that they had experienced strangely calm weather.

Related: Three Critical Realities All Leaders Must Face

Effective leaders must take all information, not just recent results, into account when making high-pressure decisions. This bias is also exacerbated when interacting with the overconfidence bias, as high-powered leaders who already have a propensity for overconfidence are more likely to assume that the most recent evidence is good, having been correct in the past.

Roberto goes into more depth about the causes of the tragedy on Everest (and I highly recommend you read the entire study for even more insight into leadership dynamics and group communication), but it's clear that if Hall and Fischer had possessed a working knowledge of cognitive biases, they may have been able to avert the disaster.

Your effectiveness as a leader depends on your ability to foresee small problems before they engorge into uncontrollable complications. Doing the work to identify where your problematic areas are can not only make you a better leader, but can help others to be better leaders, too.

Entrepreneur, business advisor and online-marketing professional

Want to be an Entrepreneur Leadership Network contributor? Apply now to join.

Editor's Pick Red Arrow

- Lock The Average American Can't Afford a House in 99% of the U.S. — Here's a State-By-State Breakdown of the Mortgage Rates That Tip the Scale

- Richard Branson Shares His Extremely Active Morning Routine : 'I've Got to Look After Myself'

- Lock This Flexible, AI-Powered Side Hustle Lets a Dad of Four Make $32 an Hour , Plus Tips: 'You Can Make a Substantial Amount of Money'

- Tennis Champion Coco Gauff Reveals the Daily Habits That Help Her Win On and Off the Court — Plus a 'No Brainer' Business Move

- Lock 3 Essential Skills I Learned By Growing My Business From the Ground Up

- 50 Cent Once Sued Taco Bell for $4 Million. Here's How the Fast-Food Giant Got on the Rapper's Bad Side .

Most Popular Red Arrow

She grew her side hustle sales from $0 to over $6 million in just 6 months — and an 'old-school' mindset helped her do it.

Cynthia Sakai, designer and founder of the luxury personal care company evolvetogether, felt compelled to help people during the pandemic.

I Started Over 300 Companies. Here Are 4 Things I Learned About Scaling a Business.

It takes a delicate balance of skill, hard work and instinct to grow a successful business. This serial entrepreneur loves the unique challenge; here are the key lessons she's learned along the way.

'Why Shouldn't They Participate?': AT&T CEO Calls on Big Tech to Help Subsidize Internet Access

AT&T's CEO called out the seven biggest tech companies in the world.

'Cannot Stop Crying': Hooters Employees Shocked After Dozens of Restaurants Suddenly Close Without Warning

The chain is the latest fast-casual restaurant to face difficult decisions amid inflation.

5 SEO Techniques to Help Your SaaS Business Rank in 2024

Discover five game-changing SEO techniques that can help you rely less on paid ads and cut down your customer acquisition costs.

Disney World Is Making a Major Change to Its Popular Genie+ System — Here's What to Know

Resort guests can now book a ride up to a week in advance among other changes.

Successfully copied link

Academia.edu no longer supports Internet Explorer.

To browse Academia.edu and the wider internet faster and more securely, please take a few seconds to upgrade your browser .

Enter the email address you signed up with and we'll email you a reset link.

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

Mount Everest Case Study Analysis (from "High-Stakes Decision Making: The Lessons of Mount Everest" case)

Mount Everest case demonstrates just how important leadership is for a group that works towards a common goal. This case doesn’t only provide information that can be applied to studying extreme sports team dynamics. It rather suggests that the “right” leadership must be present to ensure the success of any common venue. The leaders of the two expeditions presented in the case, Hall and Fischer, underestimated the importance of maintaining a strong team culture within a group of people who were driven by self-interest, which lead to the subsequent failure of both expeditions. If Hall and Fischer dedicated more effort towards building trust among the team members and communicated their beliefs more clearly, the result wouldn’t have been so unfortunate. Otherwise, the expeditions had a low chance of success from its beginning.

Loading Preview

Sorry, preview is currently unavailable. You can download the paper by clicking the button above.

RELATED TOPICS

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

- Find new research papers in:

- Health Sciences

- Earth Sciences

- Cognitive Science

- Mathematics

- Computer Science

- Academia ©2024

- Harvard Business School →

- Faculty & Research →

- November 2002 (Revised January 2003)

- HBS Case Collection

Mount Everest-1996

- Format: Print

- | Language: English

- | Pages: 22

More from the Author

- October 2013

- Faculty Research

Decision Making at the Top: The All-Star Sports eBusiness Division

Everest leadership and team simulation.

- November 2006

- Harvard Business Review

Facing Ambiguous Threats

- Decision Making at the Top: The All-Star Sports eBusiness Division By: David A. Garvin and Michael A. Roberto

- Everest Leadership and Team Simulation By: Michael A. Roberto and Amy C. Edmondson

- Facing Ambiguous Threats By: Michael A. Roberto, Richard M.J. Bohmer and Amy C. Edmondson

Press Release

Climate change and human impacts are altering mt. everest faster and more significantly than previously known.

National Geographic Rolex Logo Lockup

Photograph by National Geographic Rolex Logo Lockup

November 20, 2020 Washington, D.C . -- Today, new findings from the most comprehensive scientific expedition to Mt. Everest in history have been released in the interdisciplinary scientific journal One Earth . Featuring a collection of research papers and commentaries on Mt. Everest, known locally as Sagarmatha and Chomolangma, the research identifies critical information about the Earth’s highest-mountain glaciers and the impacts they are experiencing due to climate change. As part of the 2019 National Geographic and Rolex Perpetual Planet Everest Expedition, climate scientists studied the environmental changes including Everest’s “death zone” to understand future impacts for life on Earth as global temperatures rise.

This new research fills a critical knowledge gap on the health and status of high-mountain environments, which are incredibly difficult to study due to the inhospitable environmental conditions. Key findings include:

- The highest-ever recorded sample of microplastics was found on the “Balcony” of Mt. Everest at 8,440 m, one of the last resting spots before reaching the summit. This microplastic is likely coming from the clothing and equipment worn by climbers, highlighting the impacts of humans on even the highest reaches of our planet.

- Researchers surveyed nearly 80 glaciers around Mt. Everest and found evidence of consistent glacial mass loss over the last 60 years and that glaciers are thinning, even at extreme altitudes above 6,000 m. Using declassified spy satellites and a new highest-resolution data set, this is the most complete assessment of the status of the world’s highest glacier as a baseline for future research on its changes.

- Additionally, the research captures the first documented surge of a glacier (when it moves 10 to 100 times faster than it normally does) in the Mt. Everest region, a phenomenon that can put people and communities at risk.

Glaciers like those on Everest provide ⅕ of the global population with a steady supply of fresh water around the world. But due to the extreme conditions of these high mountains, little information up until now has existed about the impacts of climate change at elevations above 5,000m.

“Mountains and their rapidly-disappearing glaciers are the “water towers” of our planet, storing and transporting freshwater to nearly two billion people around the world. That water supply is increasingly under threat due to rising temperatures, melting glaciers, pollution, and other human-caused and environmental stressors,” said Paul Mayewski, Scientific and Expedition Lead, and Director, Climate Change Institute University of Maine, and lead author of the preview “Pushing Climate Change Science to the Roof of the World” published in One Earth.

Microplastic pollution at the highest point on Earth is a direct result of increased tourism and waste accumulation. A large proportion of that waste is made out of non-biodegradable plastic. While visible plastic has been reported on Mt. Everest previously, the pristine environment at Earth’s highest peaks is changing. The new data highlights that the collected snow samples had significantly more microplastics compared to the stream samples, with the majority of microplastics being fibrous.

“With increased tourism, microplastics throughout Mt. Everest is expected to rise, creating issues for the environment and people of the Khumbu region,” said Imogen Napper, National Geographic Explorer and first author of “Reaching New Heights in Plastic Pollution — Preliminary Findings of Microplastics on Mount Everest."

Results from the highest weather stations in the world demonstrate that the majority of precipitation to the Mt. Everest region is sourced in the Bay of Bengal, highlighting the importance of atmospheric circulation to high mountain glaciers. Further, the weather stations enabled a full reconstruction of climber’s oxygen availability during past Everest summit attempts to generate a comparison of climbing difficulty.

From April to May 2019, an international, multidisciplinary team of scientists conducted the most comprehensive single scientific expedition to Mt. Everest in the Khumbu Region of Nepal as part of the National Geographic and Rolex partnership. Team members from eight countries, including 17 Nepali researchers conducted trailblazing research in five areas of science that are critical to understanding environmental changes and their impacts: biology, glaciology, meteorology, geology and mapping.

Scientists are now utilizing the samples and data they collected during the Expedition to gain unique insights into how climate change and human populations are affecting even the highest reaches of our planet. Even the highest glaciers on Earth are reeling from human activity around the globe.

“Mountains will outlast us,” the One Earth editorial team wrote in its “The Changing Face of Mountains” editorial. “But without immediate action and integrated approaches to adaptation and sustainable development, they will lose their majesty. They will become diminished. With consequences for us all.”

Papers from the National Geographic collaboration include:

- King et al.: “Six decades of glacier mass changes around Mt. Everest revealed by historical and contemporary images,” an Article publishing in One Earth (ONEEAR266)

- Napper et al.: “Reaching new heights in plastic pollution – preliminary findings of microplastics on Mount Everest,” an Article publishing in One Earth (ONEEAR267)

- Perry et al.: “Precipitation Characteristics and Moisture Source Regions on Mt. Everest in the Khumbu, Nepal,” an Article publishing in One Earth (ONEEAR258)

- Matthews et al.: “Into Thick(er) Air? Oxygen Availability at Humans’ Physiological Frontier on Mount Everest,” an Article publishing in iScience (ISCI101718)

- Elvin et al.: “Behind the scenes of a comprehensive scientific expedition to Mt. Everest,” a Backstory publishing in One Earth (ONEEAR253)

- Mayewski et al.: “Climate Change in the Hindu Kush Himalayas: Basis and Gaps,” a Reflection publishing in One Earth (ONEEAR254)

- Miner et al.: “An overview of physical risks in the Mt. Everest region,” a Primer publishing in One Earth (ONEEAR255)

- “Voices from the roof of the world,” a collection of 6 Voices publishing in One Earth (ONEEAR252)

- Mayewski et al.: “Pushing Climate Change Science to the Roof of the World,” a Preview publishing in One Earth (ONEEAR268)

- Elmore et al.: “Understanding the World’s Water Towers through High-Mountain Expeditions and Scientific Discovery,” a Preview publishing in One Earth (ONEEAR264)

- “Everest Night Lights,” a Visual Earth publishing in One Earth (ONEEAR265)

- “Birth of Sagarmatha,” a Visual Earth publishing in One Earth (ONEEAR269)

This work was supported by the National Geographic Society and Rolex. To learn more about the Everest Expedition, please visit: https://www.nationalgeographic.org/projects/perpetual-planet/everest/ and tune into our YouTube page to get a closer look at the 2019 National Geographic and Rolex Perpetual Planet Everest Expedition

Related Files:

PDFs of all papers

Selection of images available for media use

To embed videos related to the National Geographic and Rolex Perpetual Planet Everest Expedition, please visit:

- Everest Expedition

- Meteorology

- 360: The Science

- 360: The Mission

Media Contact

The National Geographic Society is a global nonprofit organization that uses the power of science, exploration, education and storytelling to illuminate and protect the wonder of our world. Since 1888, National Geographic has pushed the boundaries of exploration, investing in bold people and transformative ideas, providing more than 15,000 grants for work across all seven continents, reaching 3 million students each year through education offerings, and engaging audiences around the globe through signature experiences, stories and content.

To learn more, visit www.nationalgeographic.org or follow us on Instagram , LinkedIn, and Facebook .

- Case Studies

Strategy & Execution

Mount Everest--1996

Mount Everest--1996 ^ 303061

Want to buy more than 1 copy? Contact: [email protected]

Are you an educator?

Register as a Premium Educator at hbsp.harvard.edu , plan a course, and save your students up to 50% with your academic discount.

Product Description

Publication Date: November 12, 2002

Source: Harvard Business School

The Inside the Case video that accompanies this case includes teaching tips and insight from the author (available to registered educators only). Describes the events that transpired during the May 1996, Mount Everest tragedy. Examines the flawed decisions that climbing teams made before and during the ascent. Teach this case online with new suggestions added to the Teaching Note.

This Product Also Appears In

Buy together, related products.

Leadership Lessons of Mount Everest

Banc One--1996

India in 1996

Copyright permissions.

If you'd like to share this PDF, you can purchase copyright permissions by increasing the quantity.

Order for your team and save!

The marketplace for case solutions.

Mount Everest – 1996 – Case Solution

This case study discusses the Mount Everest tragedy which happened sometime in May of 1996. It looks into the critical decisions that the climbing teams came up with before and during the event.

Michael A. Roberto; Gina M. Carioggia Harvard Business Review ( 303061-PDF-ENG ) November 12, 2002

Case questions answered:

We have uploaded two case solutions, which both answer the following questions:

- Why did this tragedy on Mount Everest occur? What is the root cause of the problem?

- Are tragedies such as this simply inevitable in a place like Mount Everest?

- What is your evaluation of Scott Fisher and Rob Hall as leaders? Did they make some poor decisions? If so, why?

- What are the lessons from this Mount Everest – 1996 case for general managers in business enterprises?

Not the questions you were looking for? Submit your own questions & get answers .

Mount Everest - 1996 Case Answers

You will receive access to two case study solutions! The second is not yet visible in the preview.

1. Why did this tragedy occur on Mount Everest? What is the root cause of the problem?

Hiking Mount Everest is a risky activity and the aim of every professional climber. It looks like the power of nature and mountains is unconquered. However, every year, the best of the best is trying to prove it wrong. They find themselves in Nepal to fight the elements and to summit the top of the world.

In my opinion, there is the only factor that generalizes all the roots of the tragedy. This is, let us say, a base of the source. At the beginning of the 1990s, the commercialization of Everest began.

The first commercial expeditions to Mount Everest started to offer mountain tour guides who were there to realize the dream of every climber. They deliver it all-inclusive. It includes the delivery of participants to the base camp, organization of the routes, and settlement at the camps on the way, training, acclimatization, and others.

However, summiting is still not guaranteed. Simple huh? All of that was for 65,000 USD back in 1996. In pursuit of big money, the mountain guides and the companies accept to take clients with little climbing experience. This they do even if it is clear that they would not have a single chance to summit.

Organizers start to act extremely irresponsibly towards the mountain, which takes away the lives of people year by year. In the history of Mount Everest, there have already been up to 250 deaths (only known ones).

The main reasons for tragedies are avalanches, severe weather conditions, fallings from height, health issues such as lack of oxygen, frostbite, etc.

Back to irresponsibility. During the expeditions in 1996, the climbing was not well prepared. In the preparation stage of the voyage of Mountain Madness, it was purchased an insufficient amount of oxygen equipment, which was a critical moment later.

There were also old-fashioned radio sets that weren’t working regularly, which did not allow guides to stay connected to the base camp during the climb.

Tour guides were even ignoring the precautious measures and continued the planned summiting the day when the weather was not expected to be good. They also did not follow instructions when it was agreed to start descending at 2 PM, and they did not turn back those who were running late.

Of course, hacking Mount Everest is all about natural power, weather conditions, experience, and probably some luck. However, the rules that started to be broken in pursuit of huge revenues with the commercialization of Everest appeared to be fatal back in 1996.

” We don’t need competition between people. There is competition between every person and this mountain. The last word always belongs to the mountain” – Anatoli Boukreev.

2. Are tragedies such as this simply inevitable in a place like Mount Everest?

This sort of tragedy is inevitable in a place like Everest. That’s totally true. Climbing is a dangerous activity by itself, but it becomes too risky when it comes to the summit, almost reaching 9000 meters above sea level when the human body is not supposed to function at this sort of altitude.

The smallest mistake or recklessness will cost a life. Every person deciding to summit Mount Everest realizes that it can be their last climb.

The best thing a human being can do is to maximally prepare physically and mentally, plan the schedule of acclimatization and summiting, observe the weather forecast, acquire necessary equipment, and follow regular instructions for hiking an 8000-meter peak. This gives no guarantees; however, it minimizes the risk of fatality by human mistake.

3. What is your evaluation of Scott Fisher and Rob Hall as leaders? Did they make some poor decisions? If so, why?

Rob Hall and Scott Fisher were among the first mountain guides to start the commercial guided tour to Mount Everest. Beginning in 1992, Rob Hall founded the first expedition-guiding company, Adventure Consultants.

With vast experience in climbing at a high altitude, he successfully summited Mount Everest 5 times and guided 39 clients to the top. Rob was considered the safest guide, and that’s why he was charging more than his competitor companies.

Rob seemed to be determined to his rules and always explained the process of climbing the summit. He was well-organized, experienced, and responsible.

He did a great job providing an acclimatization routing. His team of tour guides consisted of two climbers: one with more experience and the other with less. Rob did not have…

Unlock Case Solution Now!

Get instant access to this case solution with a simple, one-time payment ($24.90).

After purchase:

- You'll be redirected to the full case solution.

- You will receive an access link to the solution via email.

Best decision to get my homework done faster! Michael MBA student, Boston

How do I get access?

Upon purchase, you are forwarded to the full solution and also receive access via email.

Is it safe to pay?

Yes! We use Paypal and Stripe as our secure payment providers of choice.

What is Casehero?

We are the marketplace for case solutions - created by students, for students.

Leading a Team to the Top of Mount Everest

This transcript has been edited for length and clarity.

Brian Kenny: In 1922, a British team led by George Mallory set out to be the first ever to scale the summit of Mount Everest. They failed. In 1924 during a second attempt, they disappeared altogether. Since then, thousands of people have made the attempt; many have succeeded while others have succumbed to the brutal conditions at 29,000 feet above sea level. What does it take to successfully lead a team to the top of the highest peak in the world? Today we'll speak with Professor Amy Edmondson about Everest: A Leadership and Team Simulation . I'm your host Brian Kenny and you're listening to Cold Call.

Professor Edmondson teaches MBA and doctoral students as well as executives at Harvard Business School. Her areas of expertise include leadership, teams, innovation, and organizational learning. I think those are all pretty well appropriate for the conversation we're going to have today. Amy, welcome.

Amy : Thank you, delightful to be here.

Kenny: Set up the scenario for us about the simulation.

Edmondson: We designed the simulation to create conditions whereby (participants) have to share information and share it extremely, thoughtfully, and systematically, while requiring them to listen intently to each other in order to solve a series of challenges along the way in a pseudo climb of Everest.

We used Everest as the backdrop because it's engaging, it's exciting, it's exhilarating. The simulation is not really about Everest, it just uses that context. What it's about is the very real challenges of people in diverse teams, meaning teams with diverse expertise trying to make decisions, trying to solve problems, trying to forge new territory. That's a challenging interpersonal and technical activity. We created the simulation to give students an experience of just how challenging that can be.

Kenny: Why did you choose to do a simulation rather than just write a case about it?

Edmondson: One of the reasons that a simulation is appropriate is that it puts people in a situation where, at first glance, they think it should be relatively easy. We do the simulation each year with all of the MBA students, and most of them will take one look at it and they'll see what information they have, and they'll see what the task ahead is, and they won't be daunted by it. They think it looks pretty straightforward, and it is—but only if you listen deeply to what each other have to say.

The first and most powerful reason to use a simulation is that a great number of the teams will not do as well as they thought ... and it's an emotional experience. Whereas (in some other case studies) you sometimes can sit back and think, "Oh yeah, I would have done fine in that situation if I were really in it."

This isn't really being in the situation, but it's one step closer to being in an actual situation, having to take action, having to sort through ambiguous data, make decisions, and see how well you do. Another big difference here with cases is that there are right answers in this simulation and you can come to them if, again, if you manage the process well. It gives (students) an opportunity to realize they may not be as good team members as they thought they were.

Kenny: Explain what the team looks like. One of the things I enjoyed about this, and I think probably the participants did too, there's a bit of gamification to this. You sort of feel like you're playing a game or play acting in some ways. Who were the members of the team?

Edmondson: You are playing a game and you are play acting in a very real way. There are five members of each team, and the participants are usually randomly assigned. All of those folks have their own distinct backgrounds or back stories, if you will, and they also have access because of their expertise and because of their life stories, to different data, different information. Only by sharing that different information can the teams do well, make good decisions.

Kenny: How much do the students know? As they are sitting down have they been given a briefing document or do they just sit down and told, "This is your role"?

Kenny: I should also say that this is a multimedia case, meaning that there are videos components. One of the videos that the students watch before they begin the simulation is (an interview with) somebody who actually scaled Mount Everest and what he describes is a pretty daunting experience.

Edmondson: Jim Clarke, who's one of our wonderful alumni, did an actual Everest climb and he describes in just a terrific interview some of the features of that climb, the preparation you need, the training, the tools, the equipment. One of my favorite parts of the interview with Jim Clarke is when he says once you get above the Hillary Step, basically it takes maybe five breaths to take one step. I think in a way the video makes students over cautious, which doesn't always help them.

Kenny: It's a great dietary aid too because I think he said he burned 16,000 calories a day…

Edmondson: And you're not hungry.

Kenny: And you're not hungry. I think it probably does put some fear in the participants but that's important, right? Because as they go through this process they need to be factoring in all of these different physical elements of the climb.

Edmondson: They do need to be careful, they need to be systematic, they need to be disciplined. They don't need to be superstitiously risk averse. In other words, what is not helpful is saying, "Oh, the weather doesn't look good, we'll just stay here" or, "Oh, you look like your health is faltering a little, we'll just stay here." You can't climb the mountain if you don't climb the mountain.

Kenny: What is the goal then, what's the ultimate goal for each team?

Edmondson: The goal is to climb the mountain, and the goal is to get everybody up the mountain. That's the way you get the most points.

Kenny: What are some of the challenges that the teams are going to encounter as they're scaling the mountain?

Edmondson: They know already that they have the challenge of safely climbing the mountain. What they don't know is that at various points on the climb they'll be hit by an unexpected challenge. I won't tell you here for purposes of suspense for the simulation exactly what those are, but they're each challenges that the team can absolutely solve if they use the information they have.

Kenny: You've done this with MBA students, you've also done it with students in our executive education program. They're different just by virtue of the fact that some have more experience and more team dynamics than others. How they come at this? Do they come at it differently?

Edmondson: On average the MBA students will do a little bit better because this really is a simulation in which you have to take the number seriously, you have to take the process seriously. The executives have a slightly higher tendency to shoot from the hip.

Kenny: I bet they enjoy this, I bet this is kind of a fun.

Edmondson: They love it, they love it. Another thing we do with the MBAs, and I occasionally do this with the executives, is we give them little cameras and we ask them to videotape their team process while they're having these discussions. Then we send them back to watch certain segments of their videotapes.

Kenny: Pretty amazing and probably very similar to the kinds of conversations that we all have every day with our own teams at work.

Edmondson: Absolutely. In fact the real goal of the simulation was that the premise that in order to make good team decisions, and when you have diverse skills, diverse expertise gathered around the table, you've got to thoughtfully, systematically share those insights, share those areas of expertise. Yet, it is so much harder than most people think it is.

The second thing is that we come around the table with some shared goals, of course, but we also have some conflicting goals, and we don't usually deal with those as thoughtfully as we should.

Kenny: Have you been to Mount Everest?

Edmondson: I have not. I have been to Nepal, I've been to Kathmandu. But I have not been to Everest.

Kenny: Closer than most.

Edmondson: Yes, closer than most.

Kenny: Amy, thanks so much for joining me today.

Edmondson: My pleasure. Thank you Brian.

Kenny: You can find Everest: A Leadership and Team Simulation along with thousands of cases in the HBS case collection at hbr.org. I'm your host Brian Kenny and you've been listening to Cold Call, the official podcast of Harvard Business School.

Read more

Close

- 25 Jun 2024

- Research & Ideas

Rapport: The Hidden Advantage That Women Managers Bring to Teams

- 27 Jun 2016

These Management Practices, Like Certain Technologies, Boost Company Performance

How transparency sped innovation in a $13 billion wireless sector.

- 11 Jun 2024

- In Practice

The Harvard Business School Faculty Summer Reader 2024

- 24 Jan 2024

Why Boeing’s Problems with the 737 MAX Began More Than 25 Years Ago

- Problems and Challenges

- Strategic Planning

- Groups and Teams

- Management Teams

- Cooperation

- Interpersonal Communication

Sign up for our weekly newsletter

- Their Choice

- Choose to Lead

- Tomorrow’s Choices, Today

- Show Me the Data

- Our mission

- Let’s collaborate

Bad decisions put to the test on Mount Everest

Or how cognitive biases proved to be the downfall of experienced mountaineers.

- Tomorrow's Choices, Today

- Bad decisions put to the…

In May 1996, two rival mountaineering companies embarked upon a new ascent of Mount Everest. The expeditions were led respectively by the charismatic Rob Hall and Scott Fischer, who aimed to take their new clients to the top of the world. On the 10th of May, the two teams were descending from the summit when they were caught out by a violent storm. The leaders of both groups of climbers, as well as two of their clients and a guide, died that day, unable to reach the nearest base camp.

Climbing Everest is no trivial matter. Since the first ascent in 1950, 280 people are believed to have met their end there. Though it is still not the world’s most dangerous mountain: Annapurna I, K2 and Nanga Parbat all have fatality rates of between 20% and 28%. Compared with these deadly rivals, it could be argued that Everest has been the most climbed and is one of the safest mountains. So why is it that experienced, well-equipped professionals (who had, among other things, bottled oxygen) ended up making a series of bad decisions that ultimately condemned them to death?

Cognitive biases, or why our choices are not always logical

In 1970, two big names from the world of psychology, Amos Tversky and Daniel Kahneman, sparked a revolution by proving that humans are not rational creatures and that our choices are not always logical. In other words, many of our judgements, choices and decisions are often the result of largely arbitrary rules, rather than of statistical and logical calculations. This is mainly due to the existence of “cognitive biases”, a sort of subconscious neurological mechanism that can influence or disrupt our relationship to reality, impacting our opinions and behaviours without us noticing.

According to Kahneman, the source of these biases lies in the complex interplay of two systems in our brain, which he labels “System 1” and “System 2” . He argues that in System 1 the brain forms thoughts in a fast, automatic way. It makes decisions spontaneously and instinctively, often guided by emotions. In System 2, thoughts are formed in a slower, more deliberative way. The brain makes decisions consciously and rationally.

The downside of System 2 is that it assumes you have the time and desire to engage in deep reflection. For practical reasons, most of our day-to-day decisions are therefore made by System 1; if all our decisions were based on a drawn-out thought process, it would take days and we would have no time for anything else.

Most of the time, the shortcuts that our brain creates via System 1 are both useful and sensible. They allow us to quickly sort and interpret the information we receive, so that we can take action. Sometimes, however, things can go wrong. The shortcuts taken by our fast brain (System 1) can at times prove harmful. In such instances, we talk about “cognitive biases” – the name given to the many shortcuts in thinking that, rather than taking us safely and efficiently to the right destination, instead lead us into trouble.

Cognitive biases tested on Mount Everest

In 2002, six years after the incident on Everest, Michael Roberto, a research assistant at Harvard Business School, investigated the accident that cost the lives of some of those on the expedition. After analysing the accounts of the survivors and questioning them carefully on the sequence of events leading up to the incident, he established that at least three key cognitive biases could have led to bad decisions being made during the ascent , contributing to the catastrophic outcome.

The “sunk cost fallacy” entails sticking with a decision that you know is a bad one for fear of wasting the sacrifices you have made so far. This could explain why the climbers persisted in their ascent despite a dire weather forecast and in full knowledge of the risks they were running, particularly not having enough energy or oxygen to make the descent. In his account of the expedition, the American journalist Jon Krakauer – who had been invited to join the expedition – recalls how difficult it was for certain members of the team to accept that they should turn back when the decision needed to be made. They had sacrificed so much, financially, physically and psychologically to get to where they were, that it seemed unthinkable to give up so close to the goal. In the words of Doug Hansen, one of the client mountaineers who died that day: “ I’ve put too much of myself into this mountain to quit now, without giving it everything I’ve got ”. Although Rob Hall, the leader of the expedition, was fully aware of the dangers involved in continuing the ascent and had himself set out rigid rules designed specifically to avoid any temptation to break them in a moment of weakness, he was unable to stand up to one of his clients. Worse still, he accompanied Doug Hansen on his final ascent, knowing full well that they would not have enough oxygen or strength for the descent. Neither man made it down.

They had sacrificed so much, financially, physically and psychologically to get to where they were, that it seemed unthinkable to give up so close to the goal.

The overconfidence bias involves overestimating our capabilities, skills or the strength of our judgement at the time of making a choice. It could explain the guides’ poor assessments of their own abilities. It is worth remembering that the leaders of the two expeditions were experienced mountaineers who had both climbed Everest several times and successfully taken dozens of people to the summit over the five previous years. Fischer was therefore used to brushing aside the doubts of his clients, reassuring them that everything was under control. He is said to have told a journalist: “I believe 100 percent I’m coming back…. My wife believes 100 percent I’m coming back. She isn’t concerned about me at all when I’m guiding because I’m gonna make all the right choices”. As Michael Roberto noted in his analysis, Fischer was not the only one to have boasted about having complete confidence in himself. Several other members of the expedition had similarly overestimated their physical and psychological capabilities and were in no doubt as to their ability to successfully reach the summit and make it back down.

The “recency bias” , potentially interpreted as a variant of confirmation bias (only seeing what we want to see) also seems to have played a role in the Everest drama. This biais could be what led the expedition leaders to underestimate the likelihood of a violent storm catching them off-guard, and therefore failing to prepare for such an eventuality. The weather during their recent expeditions had been good; in fact, it had been particularly mild over the previous five years. They therefore only took these medium-term observations into account, subconsciously ignoring the older weather data that clearly showed that storms were a frequent occurrence on Everest. Had they widened the scope of their analysis to include this older data, they would have recalled that in the mid-1980s – just ten years earlier – there had been no expeditions up Everest for three consecutive years due to bad weather.

A fourth bias could be at play in these events: the “authority bias” . The fact that there was a defined hierarchy among the climbers meant that some of them, particularly the guides, were reluctant to question the decisions of the leaders, even at times of crisis. For example, one of the guides is reported to have said that he did not dare express his disagreement with some of the decisions made by Rob Hall (the expedition leader), preferring to defer to the experience, status and authority of his “superior”, rather than voicing his reservations. More generally, Michael Roberto highlights that the team lacked “psychological safety” – a climate in which everyone feels able to speak up and debate differing viewpoints. Had there been a feeling of mutual trust and opportunities to calmly discuss possible differences in opinion, certain biases may well have not undermined the rationality of the expedition leaders when it was at its most vulnerable.

Understanding and recognising the existence of biases can help us to avoid certain traps, particularly when we have to make crucial decisions, whether it’s coming back from Everest safe and sound or not ruining your business (or your life).

Besides demonstrating the disastrous consequences cognitive biases can lead to in high-risk situations, the case of the 1996 expedition also shows how difficult it can be to resist them, even when we are aware of their existence and the risks they pose. The strict rules that the mountaineers had set for themselves before making their ascent – including turning back if they had not reached the summit by 2.00 p.m. – were specifically intended to protect them from any biais: they knew all too well that their judgement would be seriously impaired while approaching the summit as a result of extreme fatigue and lack of oxygen. But instead of abiding by their rules, they let their biases take over and lead them straight to their death.

Specialists believe that over 90% of our mental behaviour is subconscious and automatic, and thus that our judgements and behaviours are dictated without us being aware of it. In this context, understanding and recognising the existence of biases can help us to avoid certain traps, particularly when we have to make crucial decisions , whether it’s coming back from Everest safe and sound or not ruining your business (or your life).

- #Leadership

Author: Sophie Guignard

A graduate of ESCP and Sciences Po Paris, Sophie began her career at Lazard, then ran a magazine in Buenos Aires before joining the editorial staff of Le Monde. She then co-founded Heidi.news, in Switzerland, and now develops editorial projects for various media and events. She is the author of 'Je choisis donc je suis: comment prenons-nous les grandes décisions de notre vie’ (Flammarion, 2021) [English Translation: I choose therefore I am: how do we make the big decisions in our lives?]

License and Republishing

The Choice - Republishing rules

We publish under a Creative Commons license with the following characteristics Attribution/Sharealike .

- You may not make any changes to the articles published on our site, except for dates, locations (according to the news, if necessary), and your editorial policy. The content must be reproduced and represented by the licensee as published by The Choice, without any cuts, additions, insertions, reductions, alterations or any other modifications. If changes are planned in the text, they must be made in agreement with the author before publication.

- Please make sure to cite the authors of the articles , ideally at the beginning of your republication.

- It is mandatory to cite The Choice and include a link to its homepage or the URL of thearticle. Insertion of The Choice’s logo is highly recommended.

- The sale of our articles in a separate way, in their entirety or in extracts, is not allowed , but you can publish them on pages including advertisements.

- Please request permission before republishing any of the images or pictures contained in our articles. Some of them are not available for republishing without authorization and payment. Please check the terms available in the image caption. However, it is possible to remove images or pictures used by The Choice or replace them with your own.

- Systematic and/or complete republication of the articles and content available on The Choice is prohibited.

- Republishing The Choice articles on a site whose access is entirely available by payment or by subscription is prohibited.

- For websites where access to digital content is restricted by a paywall, republication of The Choice articles, in their entirety, must be on the open access portion of those sites.

- The Choice reserves the right to enter into separate written agreements for the republication of its articles, under the non-exclusive Creative Commons licenses and with the permission of the authors. Please contact The Choice if you are interested at [email protected] .

Individual cases

Extracts: It is recommended that after republishing the first few lines or a paragraph of an article, you indicate "The entire article is available on ESCP’s media, The Choice" with a link to the article.

Citations: Citations of articles written by authors from The Choice should include a link to the URL of the authors’ article.

Translations: Translations may be considered modifications under The Choice's Creative Commons license, therefore these are not permitted without the approval of the article's author.

Modifications: Modifications are not permitted under the Creative Commons license of The Choice. However, authors may be contacted for authorization, prior to any publication, where a modification is planned. Without express consent, The Choice is not bound by any changes made to its content when republished.

Authorized connections / copyright assignment forms: Their use is not necessary as long as the republishing rules of this article are respected.

Print: The Choice articles can be republished according to the rules mentioned above, without the need to include the view counter and links in a printed version.

If you choose this option, please send an image of the republished article to The Choice team so that the author can review it.

Podcasts and videos: Videos and podcasts whose copyrights belong to The Choice are also under a Creative Commons license. Therefore, the same republishing rules apply to them.

Recommended articles

Behind the Algorithm: Unveiling Trust Issues in AI Decisions

Navigating the new normal: Strategies for making decisions amid extreme uncertainty

The future of work: Why we need to think beyond the hype of the four-day week

Sign up for the newsletter, sign up for the newsletter.

Get our top interviews and expert insights direct to your inbox every month. The choice is yours, but we don't think you'll regret it.

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

The Everest case suggests that both of these approaches may lead to erroneous conclusions and reduce our capability to learn from experience. We need to recognize multiple factors that contribute to large-scale organizational failures, and to explore the linkages among the psychological and sociological forces involved at the individual, group ...

Mount Everest—1996. Incredible achievement and great tragedy unfolded on the treacherous slopes of Mount Everest in the spring of 1996. Ninety-eight men and women climbed successfully to the summit, but sadly, 15 individuals lost their lives. On May 10alone, 23 people reached the summit, including Rob Hall and Scott Fischer, two of the world ...

The Leadership Lessons of Mount Everest. Our Twin Otter was descending at a dangerously steep angle, but at the last minute the pilot managed to pull the nose up and ease us onto the runway. We ...

On May 10 1996, 47 people in three teams set out to climb the 8,848 metre high Mount Everest. Eight of them would not come back. This is the Rob Hall story, a case study on leadership and decision ...

5 min read. ·. Jul 8, 2021. --. "Mount Everest is a peak in the Himalaya mountain range. It is located between Nepal and Tibet. At 8,849 meters, it is considered the tallest point on Earth ...

The case revolves around the disaster tragedy that happened on Mount Everest on May 11, 1996, making it one of the deadliest days on Mount Everest up to the years 2014 and 2015, when 16 and 18 fatalities occurred during each year, respectively. On May 10, the summit of Mount Everest was reached by 23 climbers.

Mount Everest-1996 is the case study for which Roberto is perhaps best known. It explores a March 1996 tragedy in which five mountaineers from two widely-respected teams, including the teams' two leaders, Rob Hall and Scott Fischer, perished while attempting to summit Mount Everest during an especially deadly season. Roberto's examination ...

During an attempt to summit Everest in 1996 -- immortalized in Jon Krakauer's book Into Thin Air -- a powerful storm swept the mountain, obscuring visibility for the 23 climbers on return to base ...

The Inside the Case video that accompanies this case includes teaching tips and insight from the author (available to registered educators only). Describes the events that transpired during the May 1996, Mount Everest tragedy. Examines the flawed decisions that climbing teams made before and during the ascent.

Mount Everest Case Study Analysis (from "High-Stakes Decision Making: The Lessons of Mount Everest" case) Daniel Voronin. Mount Everest case demonstrates just how important leadership is for a group that works towards a common goal. This case doesn't only provide information that can be applied to studying extreme sports team dynamics.

Roberto, Michael, and Gina Carioggia. "Mount Everest-1996." Harvard Business School Case 303-061, November 2002. (Revised January 2003.)

Why study Mount Everest? Professor Roberto described what managers can learn from mountain climbing in an e-mail interview with HBS Working Knowledge senior editor Martha Lagace.. Lagace: In your new research, you tried to learn from a tragic episode on Mount Everest. You've applied a variety of theories from management to study why events on May 10, 1996 went horribly wrong.

November 20, 2020 Washington, D.C.. -- Today, new findings from the most comprehensive scientific expedition to Mt. Everest in history have been released in the interdisciplinary scientific journal One Earth.Featuring a collection of research papers and commentaries on Mt. Everest, known locally as Sagarmatha and Chomolangma, the research identifies critical information about the Earth's ...

Product Description. The Inside the Case video that accompanies this case includes teaching tips and insight from the author (available to registered educators only). Describes the events that transpired during the May 1996, Mount Everest tragedy. Examines the flawed decisions that climbing teams made before and during the ascent.

The 1996 Mount Everest disaster occurred on 10-11 May 1996 when eight climbers caught in a blizzard died on Mount Everest while attempting to descend from the summit. Over the entire season, 12 people died trying to reach the summit, making it the deadliest season on Mount Everest at the time and the third deadliest after the 23 fatalities resulting from avalanches caused by the April 2015 ...

The 1996 Mount Everest climbing disaster: The breakdown of learning in teams. October 2004; Human Relations 57(10):1263-1284; ... A case study of the Binna Burra Lodge, one of Australia's longest ...

Elmes, M. & Barry, D. Deliverance, denial, and the death zone: A study of narcissism and regression in the May 1996 Everest climbing disaster . Journal of Applied Behavioral Science, 1999, 35, 163-187 .

Mount Everest - 1996 - Case Solution. This case study discusses the Mount Everest tragedy which happened sometime in May of 1996. It looks into the critical decisions that the climbing teams came up with before and during the event. Michael A. Roberto; Gina M. Carioggia. Harvard Business Review ( 303061-PDF-ENG)

Brian Kenny: In 1922, a British team led by George Mallory set out to be the first ever to scale the summit of Mount Everest. They failed. In 1924 during a second attempt, they disappeared altogether. Since then, thousands of people have made the attempt; many have succeeded while others have succumbed to the brutal conditions at 29,000 feet ...

This award-winning simulation uses the dramatic context of a Mount Everest expedition to reinforce student learning in group dynamics and leadership. Students play one of 5 roles on a team of climbers attempting to summit the mountain. During each round of play they must collectively discuss whether to attempt the next camp en route to the summit. Ultimately, teams must climb through 5 camps ...

Bad decisions put to the…. In May 1996, two rival mountaineering companies embarked upon a new ascent of Mount Everest. The expeditions were led respectively by the charismatic Rob Hall and Scott Fischer, who aimed to take their new clients to the top of the world. On the 10th of May, the two teams were descending from the summit when they ...

First-year students find out as they participate together in, "Everest: A Leadership and Team Simulation.". Harvard Business School professor Amy Edmondson talks about the choice to use Mt ...