Click through the PLOS taxonomy to find articles in your field.

For more information about PLOS Subject Areas, click here .

Loading metrics

Open Access

Peer-reviewed

Research Article

Trauma informed interventions: A systematic review

Roles Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Project administration, Resources, Supervision, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing

* E-mail: [email protected]

Affiliations School of Nursing, The Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, Maryland, United States of America, Bloomberg School of Public Health, The Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, Maryland, United States of America

Roles Formal analysis, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing

Affiliation School of Nursing, Duke University, Durham, North Carolina, United States of America

Roles Data curation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing

Affiliation School of Public Health, University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, Minnesota, United States of America

Roles Formal analysis, Writing – review & editing

Affiliation School of Nursing, The Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, Maryland, United States of America

Roles Data curation, Writing – review & editing

Affiliation School of Nursing, Vanderbilt University, Nashville, Tennessee, United States of America

Affiliation Medstar Good Samaritan Hospital, Baltimore, Maryland, United States of America

Roles Data curation, Formal analysis, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing

- Hae-Ra Han,

- Hailey N. Miller,

- Manka Nkimbeng,

- Chakra Budhathoki,

- Tanya Mikhael,

- Emerald Rivers,

- Ja’Lynn Gray,

- Kristen Trimble,

- Sotera Chow,

- Patty Wilson

- Published: June 22, 2021

- https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0252747

- Reader Comments

Health inequities remain a public health concern. Chronic adversity such as discrimination or racism as trauma may perpetuate health inequities in marginalized populations. There is a growing body of the literature on trauma informed and culturally competent care as essential elements of promoting health equity, yet no prior review has systematically addressed trauma informed interventions. The purpose of this study was to appraise the types, setting, scope, and delivery of trauma informed interventions and associated outcomes.

We performed database searches— PubMed, Embase, CINAHL, SCOPUS and PsycINFO—to identify quantitative studies published in English before June 2019. Thirty-two unique studies with one companion article met the eligibility criteria.

More than half of the 32 studies were randomized controlled trials (n = 19). Thirteen studies were conducted in the United States. Child abuse, domestic violence, or sexual assault were the most common types of trauma addressed (n = 16). While the interventions were largely focused on reducing symptoms of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) (n = 23), depression (n = 16), or anxiety (n = 10), trauma informed interventions were mostly delivered in an outpatient setting (n = 20) by medical professionals (n = 21). Two most frequently used interventions were eye movement desensitization and reprocessing (n = 6) and cognitive behavioral therapy (n = 5). Intervention fidelity was addressed in 16 studies. Trauma informed interventions significantly reduced PTSD symptoms in 11 of 23 studies. Fifteen studies found improvements in three main psychological outcomes including PTSD symptoms (11 of 23), depression (9 of 16), and anxiety (5 of 10). Cognitive behavioral therapy consistently improved a wide range of outcomes including depression, anxiety, emotional dysregulation, interpersonal problems, and risky behaviors (n = 5).

Conclusions

There is inconsistent evidence to support trauma informed interventions as an effective approach for psychological outcomes. Future trauma informed intervention should be expanded in scope to address a wide range of trauma types such as racism and discrimination. Additionally, a wider range of trauma outcomes should be studied.

Citation: Han H-R, Miller HN, Nkimbeng M, Budhathoki C, Mikhael T, Rivers E, et al. (2021) Trauma informed interventions: A systematic review. PLoS ONE 16(6): e0252747. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0252747

Editor: Vedat Sar, Koc University School of Medicine, TURKEY

Received: July 1, 2020; Accepted: May 23, 2021; Published: June 22, 2021

Copyright: © 2021 Han et al. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Data Availability: This is a systematic review. All relevant data were extracted from the published studies included in the review.

Funding: This study was supported, in part, by a grant from the Johns Hopkins Provost Discovery Award (HRH). Additional funding was received from the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (UL1TR003098, HRH), National Institute of Nursing Research (P30NR018093, HRH; T32NR012704, HM), National Institute on Aging (R01AG062649, HRH; F31AG057166, MN), Robert Wood Johnson Foundation Health Policy Research Scholar program (MN), and Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (5T06SM060559‐ 07, PW). The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript. There was no additional external funding received for this study.

Competing interests: The authors have declared that no competing interests exist.

Despite the United States’ commitment to health equity, health inequities remain a pressing concern among some of the nation’s marginalized populations, such as racial/ethnic or gender minority populations. For example, according to the 2016 National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES), 29.1% of Mexican Americans and 24.3% of African Americans with diabetes had hemoglobin A1C greater than 9% (the gold standard of glucose control with levels ≤ 7% deemed adequate), compared to 11% in non-Hispanic whites [ 1 ]. The 2016 survey also revealed that 40.9% and 41.5% of Mexican Americans and African Americans with hypertension, respectively, had their blood pressure under control, compared to 51.7% in non-Hispanic whites. In 2014, 83% of all new diagnoses of HIV infection in the United States occurred among gay, bisexual, and other men who have sex with men, with African American men having the highest rates [ 2 ].

Several factors have been discussed as root causes of health inequities. For example, Farmer et al. [ 3 ] noted structural violence—the disadvantage and suffering that stems from the creation and perpetuation of structures, policies and institutional practices that are innately unjust—as a major determinant of health inequities. According to Farmer et al., because systemic exclusion and disadvantage are built into everyday social patterns and institutional processes, structural violence creates the conditions which sustain the proliferation of health and social inequities. For example, a recent analysis [ 4 ] using a sample including 4,515 National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey participants between 35 and 64 years of age revealed that black men and women had fewer years of education, were less likely to have health insurance, and had higher allostatic load (i.e., accumulation of physiological perturbations as a result of repeated or chronic stressors such as daily racial discrimination) compared to white men (2.5 vs 2.1, p <.01) and women (2.6 vs 1.9, p <.01). In the analysis, allostatic load burden was associated with higher cardiovascular and diabetes-related mortality among blacks, independent of socioeconomic status and health behaviors.

Browne et al. [ 5 ] identified essential elements of promoting health equity in marginalized populations such as trauma-informed and culturally competent care. In particular, trauma-informed care is increasingly getting closer attention and has been studied in a variety of contexts such as addiction treatment [ 6 – 8 ] and inpatient psychiatric care [ 9 ]. While there is a growing body of the literature on trauma-informed care, no prior review has systematically addressed trauma-informed interventions; one published review of literature [ 10 ] limited its scope to trauma survivors in physical healthcare settings. As such, the purpose of this paper is to conduct a systematic review and synthesize evidence on trauma-informed interventions.

For the purpose of this paper, we defined trauma as physical and psychological experiences that are distressing, emotionally painful, and stressful and can result from “an event, series of events, or set of circumstances” such as a natural disaster, physical or sexual abuse, or chronic adversity (e.g., discrimination, racism, oppression, poverty) [ 11 , 12 ]. We aim to: 1) describe the types, setting, scope, and delivery of trauma informed interventions and 2) evaluate the study findings on outcomes in association with trauma informed interventions in order to identify gaps and areas for future research.

Five electronic databases—PubMed, Embase, Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL), SCOPUS and PsycINFO—were searched from the inception of the databases to identify relevant quantitative studies published in English. The initial literature search was conducted in January 2018 and updated in June 2019 using the same search strategy.

Review design

We conducted a systematic review of quantitative evidence to evaluate the effects of trauma informed interventions. Due to heterogeneity relative to study outcomes, designs, and statistical analyses approaches among the included studies, we qualitatively synthesized the study findings. Three trained research assistants extracted study data. Specifically, we used the PICO framework to extract and organize key study information. The PICO framework offers a structure to address the following questions for study evidence [ 13 ]: Patient problem or population (i.e., patient characteristics or condition); Intervention (type of intervention tested or implemented); Comparison or control (comparison treatment or control condition, if any), and Outcome (effects resulting from the intervention).

Eligibility

Inclusion criteria..

Articles were screened for their relevance to the purpose of the review. Articles were included in this review if the study was: about trauma informed approach (i.e., an approach to address the needs of people who have experienced trauma) or an aspect of this approach, published in English language and involved participants who were 18 years and older. Also, only quantitative studies conducted within a primary care or community setting were included.

Exclusion criteria.

Exclusion criteria were: studies in or with military populations, refugee or war-related trauma populations, studies with mental health experts and clinicians as research subjects or studies of incarcerated and inpatient populations. Conference abstracts that had limited information on study characteristics were also excluded.

Search strategy and selection of studies

Search strategy..

Following consultation with a health science librarian, peer-reviewed articles were searched in PubMed, Embase, CINAHL, SCOPUS and PsycINFO using MeSH and Boolean search techniques. Search terms included: "trauma focused" OR "trauma-focused" OR "trauma informed" OR "trauma-informed." We also searched for the term trauma within three words of informed or focus ((trauma W/3 informed) OR (trauma W/3 focused), or (traumaN3 (focused OR informed)). Detailed search terms for each database are provided in Appendix 1.

Study selection.

The initial electronic search yielded 7,760 references and the follow-up search yielded 5,207 which were all imported into the Covidence software for screening [ 14 ]. Screening of the references was conducted by 2 independent reviewers and disagreements were resolved through consensus. There were 4,103 duplicates removed from the imported articles and 8,864 studies were forwarded to the title and abstract screening stage. Eight thousand five hundred and twenty-one studies were excluded because they were irrelevant. Three hundred and forty-three abstracts were identified to be read fully. Following this, 311 articles were excluded for focusing on other psychological conditions (n = 120), were non-experimental studies (n = 78) and were in inpatient or incarcerated populations (n = 46). One additional companion article was identified during full text review. Therefore, thirty-three articles met the inclusion criteria and are reported in this review. Fig 1 provides details of the selection process and identifies the reasons why articles were excluded at each stage.

- PPT PowerPoint slide

- PNG larger image

- TIFF original image

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0252747.g001

Quality assessment

We used the Joanna Briggs Institute quality appraisal tools [ 15 ] for randomized controlled trials (RCTs), quasi-experimental studies, and retrospective studies to assess the rigor of each study included in this review. The Joanna Briggs Institute quality appraisal tools [ 15 ] include items asking about methodological elements that are critical to the rigor of each type of study designs. In particular, one of the items for RCTs addresses participant blinding to treatment assignment. Due to the nature of trauma-informed interventions included in our review, it was decided that participant blinding is not relevant and hence was removed from the appraisal list for RCTs. No studies were excluded on the basis of the quality assessment. The quality assessment process was conducted independently by two raters. Inter-rater agreement rates ranged from 56% to 100% with the resulting statistic indicating substantial agreement (average inter-rater agreement rate = 77%). Discrepancies between raters were resolved via inter-rater discussion.

Overview of studies

Table 1 summarizes the main characteristics of the 32 unique studies included in the review, with one companion article [ 16 ] for a study which was later reported with a more thorough examination of findings [ 17 ] totaling 33 articles. More than half (n = 19) of the 32 studies were RCTs [ 17 – 35 ] whereas twelve studies were quasi-experimental [ 36 – 47 ] and one was retrospective study [ 48 ]. Thirteen studies were conducted in the U.S. [ 17 – 19 , 22 , 26 , 27 , 29 , 35 , 39 – 41 , 45 , 47 ]; five in the Netherlands [ 30 , 31 , 33 , 38 , 48 ]; three in Canada [ 23 , 25 , 46 ]; two in Australia [ 21 , 24 ]; two in the United Kingdom [ 36 , 44 ]; two in Sweden [ 42 , 43 ]; on study in Chile [ 20 ]; Iran [ 32 ]; Haiti [ 37 ]; South Africa [ 34 ]; and Germany [ 28 ]. Fourteen of the studies only included females in their sample [ 18 , 20 , 21 , 23 – 25 , 27 , 28 , 38 – 41 , 45 , 48 ]. The average sample size was 78 participants, with a range from 10 participants [ 38 ] to 297 participants [ 48 ]. Of the studies included, 67% had a sample size above 50 [ 18 – 22 , 26 , 29 – 34 , 36 , 37 , 39 – 42 , 46 – 48 ].

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0252747.t001

The studies included in this review recruited their study populations largely based on the type of trauma they were aiming to address, such as individuals that experienced interpersonal traumatic event such as child abuse, sexual assault, or domestic violence [ 16 – 18 , 20 – 22 , 24 – 26 , 35 , 40 – 43 , 45 , 46 ], individuals with substance abuse disorders [ 19 , 47 , 48 ], couples experiencing clinically significant marital issues [ 23 ], individuals with limb amputations [ 38 ], dental phobia [ 28 ], or fire service personnel suffering from post-traumatic stress disorder [ 44 ]. Trauma was self-reported in eight articles [ 16 , 17 , 20 , 22 , 26 , 34 , 35 , 47 ]. In contrast, nine studies clearly identified a measurement of trauma; the Trauma History Questionnaire [ 19 , 45 ], the Childhood Trauma Questionnaire [ 23 , 25 ], the Childhood Maltreatment Interview Schedule [ 23 ], the Revised Conflict Tactics Scale adapted for sex work [ 39 ], the Traumatic Events Screening Instrument for Adults [ 27 ], the Life Events Checklist [ 46 ], and the Adverse Childhood Experiences [ 18 ]. Two studies used a clinical tool (e.g. eye movement desensitization and reprocessing [ 38 ] and Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4 th edition [ 41 ] to identify or diagnose trauma. Fifteen studies did not include direct measurements for trauma [ 21 , 24 , 28 – 33 , 36 , 37 , 40 , 42 – 44 , 48 ].

Quality ratings

Tables 2 – 4 shows final scores of quality assessment. Quality of the 32 unique studies included in this review varied across individual studies. Twelve of 19 RCTs included in the review were of high quality (i.e., 9 to 11) [ 17 , 18 , 20 , 21 , 24 , 26 , 28 , 29 , 31 , 33 – 35 ] and six were of medium quality (i.e., 5 to 8) [ 19 , 22 , 23 , 25 , 27 , 30 ]. One study scored 4 of 12 [ 32 ]. The low rating study [ 32 ] lacked relevant information to adequately score its methodological rigor. Most RCTs clearly described randomization, group equivalence at baseline, rates and reasons for attrition, study outcomes, and analysis. Blinding of outcomes assessors to treatment assignment was used and described in several RCTs [ 17 , 20 , 21 , 24 , 27 , 35 ], whereas blinding of those delivering treatment was discussed clearly in only one study [ 25 ]. The majority of the quasi-experimental studies were of high quality (i.e., 7 or higher), except two, which scored 2 of 9 [ 37 ] and 6 of 9 [ 39 ], respectively. Six of twelve quasi-experimental studies [ 36 , 41 – 44 , 47 ] had a comparison group to strengthen internal validity of causal inferences by comparing intervention and control groups. Some of these studies, however, noted differences in baseline assessments between groups [ 36 , 43 , 44 ]. Finally, one retrospective study [ 48 ] scored 11 of 11 and hence was rated as high quality.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0252747.t002

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0252747.t003

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0252747.t004

Characteristics of trauma-informed interventions

Type of intervention..

Table 5 details the trauma informed intervention characteristics included in this review. The two most frequently used interventions were eye movement desensitization and reprocessing (EMDR) [ 28 , 30 , 31 , 33 , 36 , 38 ]—a multi-phase intervention using bilateral stimulation, such as left-to-right eyes movements or hand tapping, to desensitize individuals to a traumatic memory or image—and trauma-focused cognitive behavioral therapy or cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) [ 26 , 27 , 32 , 46 , 48 ]—a psychological approach to introduce emotional regulation and coping strategies (e.g., deep muscle relaxation, yoga, thought discovery and breathing techniques) to deal with negative feelings and behaviors surrounding a trauma of interest [ 32 , 48 ]. The implementation of CBT varied on the trauma of interest. Other studies implemented interventions using general trauma focused therapy [ 22 , 43 ], emotion focused therapy [ 23 , 25 ], stress reduction programs [ 17 ], cognitive processing therapy [ 24 ], brief electric psychotherapy [ 31 ], present focused group therapy [ 26 ], compassion focused therapy [ 44 ], prolonged exposure [ 45 ], stress inoculation training [ 45 ], psychodynamic therapy [ 45 ], and visual schema displacement therapy [ 30 ]. A number of studies included more than one of these therapies [ 13 , 26 , 30 , 31 , 33 , 36 , 45 ].

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0252747.t005

Setting, scope, and delivery of intervention.

Twenty of the interventions were identified to occur in an outpatient clinic/setting [ 19 – 21 , 24 , 25 , 27 – 29 , 31 – 34 , 36 , 39 , 40 , 42 , 43 , 46 – 48 ]. Four of the studies took place in a research lab or office [ 23 , 26 , 41 , 45 ], one study occurred in the community [ 17 ], and one study implemented therapy in three locations, two of which were outpatient and one of which was a residential treatment center [ 47 ]. Lastly, one study occurred in internally displaced people’s camps within a metropolitan area in Haiti [ 37 ]. The remaining studies did not identify a specific setting [ 22 , 35 , 38 , 44 ].

The interventions ranged in length and time, but most often occurred weekly. The longest intervention was done by Lundqvist and colleagues [ 43 ], which lasted a total length of 2-years and included 46 sessions. Several other studies included 20 sessions or more [ 18 , 22 , 23 , 25 , 26 ]. The interventions were most commonly delivered by medical professionals, including but not limited to: psychologists or psychiatrists, therapists, social workers, mental health clinicians and physicians [ 16 , 17 , 20 – 29 , 33 , 36 , 38 , 39 , 41 , 44 – 47 ]. The articles frequently noted that the interventionists were masters-level-prepared or higher in their profession [ 21 , 23 , 25 – 27 , 33 , 40 , 47 ]. In addition to standard education and licensure, many of the professionals implementing the interventions were required to obtain further training in the therapy of interest [ 23 – 25 , 27 – 30 , 33 , 36 , 38 – 40 , 46 , 47 ]. Two studies were identified to be delivered by lay persons [ 34 , 37 ].

Fidelity was addressed in 16 of the included articles [ 16 , 19 , 21 , 23 , 24 , 26 – 30 , 33 – 35 , 45 – 47 ]. The manner in which fidelity was addressed varied by study. Videotaping or audiotaping therapy sessions [ 21 , 23 , 24 , 28 – 30 , 33 , 35 ] were most common, followed by deploying regular supervision of the therapy sessions [ 21 , 23 , 27 , 29 , 33 , 46 ], using a training manual or intervention protocols [ 19 , 21 , 33 , 46 ], or having individuals unaffiliated with the study or blind to the intervention rate sessions [ 21 , 26 , 28 , 35 ]. Additionally, three articles utilized fidelity checks/checklists to ensure components of the intervention were addressed [ 16 , 30 , 47 ] or had patients and/or therapists rate therapy sessions [ 26 , 34 , 45 ]. Finally, one study had quality assurance worksheets completed after each session that were later reviewed by the study coordinator [ 34 ].

Effects of trauma-informed interventions

Trauma-informed interventions were tested to improve several psychological outcomes, such as post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), depression, and anxiety. The most frequently assessed psychological outcome was PTSD, which was examined in 23 out of the 32 studies [ 17 , 20 – 27 , 31 , 33 , 35 – 39 , 41 , 42 , 44 – 48 ]. Among the studies that assessed PTSD as an outcome, 11 found significant reductions in PTSD symptoms and severity following the trauma-informed intervention [ 17 , 20 , 21 , 24 , 26 , 28 , 34 , 42 , 45 – 47 ], however, one of these studies, which utilized outpatient psychoeducation, did not find significant differences in reduction between the intervention and control group [ 20 ]. Trauma-informed interventions that were associated with a significant reduction in PTSD were a mindfulness-based stress reduction program [ 16 ], two therapies using the Trauma Recovery and Empowerment Model (TREM) [ 47 ], CBT [ 26 , 46 ], EMDR [ 28 ], general trauma-focused therapy [ 42 ], psychodynamic therapy [ 45 ], stress inoculation therapy [ 45 ], present-focused therapy [ 26 ], and cognitive processing therapy [ 24 ]. In addition, an intervention designed to reduce stress and improve HIV care engagement improved PTSD symptoms; however, this intervention was not intended to treat PTSD [ 34 ].

Other commonly assessed psychological symptoms, including depression and anxiety, were examined in 16 [ 17 – 21 , 24 – 26 , 29 , 31 , 32 , 35 , 40 , 44 , 47 , 48 ] and 10 [ 21 , 24 , 25 , 28 , 29 , 35 , 36 , 44 , 47 , 48 ] studies, respectively. Among these, trauma-informed interventions were associated with decreased or improved depressive symptoms in 9 studies [ 17 , 18 , 20 , 21 , 24 , 32 , 35 , 47 , 48 ] and decreased or improved anxiety in 5 studies [ 21 , 28 , 35 , 47 , 48 ]. For example, Vitriol and colleagues found that outpatient psychoeducation resulted in improved depressive symptoms in women with severe depression and childhood trauma [ 20 ]. Similarly, Kelly and colleagues found that female survivors of interpersonal violence experienced a significantly greater reduction of depressive symptoms in the intervention group (mindfulness-based stress reduction) compared to the control group [ 16 , 17 ]. Other therapies that resulted in improved depressive symptoms were TREM [ 47 ], prolonged exposure therapy [ 21 ], CBT [ 32 , 46 ], psychoeducational cognitive restructuring [ 35 ], and financial empowerment education [ 18 ]. Cognitive processing therapy similarly resulted in large reductions in depression symptoms, however this reduction was also observed in the control group [ 24 ]. The same studies showed that TREM [ 47 ], prolonged exposure therapy [ 21 ], CBT [ 48 ], and psychoeducational cognitive restructuring [ 35 ] were associated with improved anxiety. Lastly, in a separate study than the one highlighted above, EMDR was associated with improved anxiety [ 28 ].

A select number of the studies found associations between trauma-informed interventions and other psychological outcomes such as attachment anxiety, attachment avoidance, psychiatric symptoms or dental distress. For example, the trauma-informed mindfulness-based reduction program implemented by Kelly and colleagues was associated with a greater decrease in anxious attachment, measured by the Relationship Structures Questionnaire, compared to the waitlist group [ 17 ]. Similarly, Masin-Moyer and colleagues found that TREM and an attachment-informed TREM (ATREM) were associated with significant reductions in group attachment anxiety, group attachment avoidance, and psychological distress in women with a history of interpersonal trauma [ 47 ]. Additionally, individuals in an outpatient substance abuse treatment program, consisting of psychoeducational seminars and trauma-informed addiction treatment, experienced significantly better outcomes of psychiatric severity, measured by the Global Appraisal of Individual Needs scale, compared to a control treatment group [ 19 ]. Doering and colleagues found that EMDR, compared to the control group, was associated with significantly greater improvement in dental stress, anxiety and fear in patients with dental-phobia [ 28 ].

There was a series of interpersonal, emotional and behavioral outcomes assessed in the included studies. For example, adult females that were sexually abused in childhood experienced a significant improvement in social interaction and social adjustment after receiving trauma focused group therapy [ 43 ]. Similarly, Dalton and colleagues found that couples that received emotion focused therapy experienced a significant reduction in relationship distress [ 23 ] and MacIntosh and colleagues found that individuals that received CBT reported lower interpersonal problems post-treatment [ 46 ]. Trauma-based interventions were also associated with emotional outcomes. Visual schema displacement therapy and EMDR both were superior to the control treatment in reducing emotional disturbance and vividness of negative memories [ 30 ]. In a separate study, CBT was found to reduce levels of emotional dysregulation in individuals that experienced childhood sexual abuse [ 46 ]. Lastly, trauma-informed interventions were associated with behavioral outcomes, including HIV risk reduction [ 26 ], decreased days of alcohol use [ 27 ], and improvements in avoidance of client condom negotiations, frequency of sex trade under influence of drugs or alcohol, and use of intimate partner violence support [ 40 ]. Interventions that were associated with these behavioral outcomes included trauma focused and present focused group therapy [ 26 ], CBT [ 27 ], and a trauma-informed support, validation, and safety-promotion dialogue intervention [ 40 ].

Publication bias

We analyzed three sets of outcome variables for publication bias: PTSD, depression, and anxiety. Based on Begg and Mazumdar test, there was no evidence of publication bias for PTSD (z = 1.55, p = 0.121) and anxiety (z = 0.29, p = 0.769). However, there was some evidence of publication bias for depression (z = 5.19, p<.001). The statistically significant publication bias for depression appears to be mainly due to large effect sizes in Nixon [ 24 ] and Bowland [ 35 ].

According to our database search, this is the first systematic review to critically appraise trauma-informed interventions using a comprehensive definition of trauma. In particular, our definition encompassed both physical and psychological experiences resulting from various circumstances including chronic adversity. Overall, there was inconsistent evidence to suggest trauma informed interventions in addressing psychological outcomes. We found that trauma-informed interventions were effective in improving PTSD [ 17 , 20 , 21 , 24 , 26 , 28 , 34 , 42 , 45 – 47 ] and anxiety [ 21 , 28 , 35 , 47 , 48 ] in less than half of the studies where these outcomes were included. We also found that depression was improved in less than about two thirds of the studies where the outcome was included [ 17 , 18 , 20 , 21 , 24 , 32 , 35 , 47 , 48 ]. Although limited in the number of published studies included this review, available evidence consistently supported trauma-informed interventions in addressing interpersonal [ 23 , 43 , 46 ], emotional [ 30 , 46 ], and behavioral outcomes [ 26 , 27 , 40 ].

Effective trauma informed intervention models used in the studies varied, encompassing CBT, EMDR, or other cognitively oriented approaches such as mindfulness exercises [ 16 , 24 , 26 , 28 , 32 , 35 , 45 , 46 , 48 ]. In particular, CBT was noted as an effective trauma informed intervention strategy which successfully led to improvements in a wide range of outcomes such as depression [ 32 , 48 ], anxiety [ 48 ], emotional dysregulation [ 46 ], interpersonal problems [ 23 , 46 ], and risky behaviors (e.g., days of alcohol use) [ 27 ]. While the majority of the studies included in the review were focused on interpersonal trauma such as child abuse, sexual assault, or domestic violence [ 16 – 18 , 20 – 22 , 24 – 26 , 35 , 40 – 43 , 45 , 46 ], growing evidence demonstrates perceived discrimination and racism as significant psychological trauma and as underlying factors in inflammatory-based chronic diseases such as cardiovascular disease or diabetes [ 4 ]. Future trauma informed interventions should consider a wide-spectrum of trauma types, such as racism and discrimination, by which racial/ethnic minorities are disproportionately affected from [ 49 ].

While the majority of the trauma informed interventions were delivered by specialized medical professionals trained in the therapy [ 16 , 17 , 20 – 29 , 33 , 36 , 38 – 41 , 44 – 47 ], several of the articles lacked full descriptions of interventionist training and fidelity monitoring [ 20 , 22 , 25 , 36 , 38 – 41 , 44 ]. Two studies were identified to be delivered by lay persons [ 34 , 37 ]. There is sufficient evidence to suggest that lay persons, upon training, can successfully cover a wide scope of work and produce the full impact of community-based intervention approaches [ 50 ]. Given such, there is a strong need for trauma informed intervention studies to clearly elaborate the contents and processes of lay person training such as competency evaluation and supervision to optimize the use of this approach.

There are methodological issues to be taken into consideration when interpreting the findings in this review. While twenty-three of 32 studies were of high quality [ 17 , 18 , 20 , 21 , 24 , 26 , 28 , 29 , 31 , 33 – 36 , 38 , 40 – 48 ], some studies lacked methodological rigor, which might have led to false negative results (no effects of trauma informed interventions). For example, about one-third (31%) had a sample size less than 50 [ 17 , 23 – 25 , 27 , 28 , 35 , 38 , 43 , 45 ]. In addition, half of the quasi-experimental studies [ 37 – 40 , 45 , 46 ] did not have a comparison group or when they had one, group differences were noted in baseline assessments [ 36 , 43 , 44 ]. In several studies, therapists took on both traditional treatment and research responsibilities (e.g., delivery of the intervention) [ 20 , 25 , 29 , 32 , 33 , 36 , 40 , 46 , 47 ], yet blinding of those delivering treatment was discussed clearly in only one study [ 25 ]. This dual role is likely to have led to the disclosure of group allocation, hence, threatening the internal validity of the results. Future studies should address these issues by calculating proper sample size a priori, using a comparison group, and concealing group assignments.

Review limitations

Several limitations of this review should be noted. First, by using narrowly defined search terms, it is possible that we did not extract all relevant articles in the existing literature. However, to avoid this, we conducted a systematic electronic search using a comprehensive list of MeSH terms, as well as similar keywords, with consultation from an experienced health science librarian. Additionally, we hand searched our reference collections, Second, the trauma informed interventions included in this review were implemented to predominantly address trauma related to sexual or physical abuse among women. Thus, our findings may not be applicable to trauma related to other types of incidence such as chronic adversity (e.g., racism or discrimination). Likewise, there were insufficient studies addressing a wider range of trauma impacts such as emotion regulation, dissociation, revictimization, non-suicidal self-injury or suicidal attempts, or post-traumatic growth. Future research is warranted to address these broader impacts of trauma. We included only articles written in English; therefore, we limited the generalizability of the findings concerning studies published in non-English languages. Finally, we used arbitrary cutoff scores to categorize studies as low, medium, and high quality (quality ratings of 0-4, 5-8, and 9+ for RCTs and 0-3, 4-6, 7+ for quasi-experimental studies, respectively). Using this approach, each quality-rating item was equally weighted. However, certain factors (e.g., randomization method) may contribute to the study quality more so than others.

Our review of 33 articles shows that there is inconsistent evidence to support trauma informed interventions as an effective intervention approach for psychological outcomes (e.g., PTSD, depression, and anxiety). With growing evidence in health disparities, adopting trauma informed approaches is a growing trend. Our findings suggest the need for more rigorous and continued evaluations of the trauma informed intervention approach and for a wide range of trauma types and populations.

Supporting information

S1 checklist..

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0252747.s001

S1 Appendix. Search strategies.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0252747.s002

Acknowledgments

We would like to express our appreciation to a medical librarian, Stella Seal for her assistance with article search. Both Kristen Trimble and Sotera Chow were students in the Masters Entry into Nursing program and Hailey Miller and Manka Nkimbeng were pre-doctoral fellows at The Johns Hopkins University when this work was initiated.

- 1. Health disparities data. 2020 May 28 [cited 28 May 2020]. In healthypeople.gov [Internet]. Available from: https://www.healthypeople.gov/2020/data-search/health-disparities-data/health-disparities-widget .

- 2. HIV and AIDS. 2018 April [cited 28 May, 2020]. In: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality [Internet]. Available from: https://www.ahrq.gov/research/findings/nhqrdr/chartbooks/effectivetreatment/hiv.html .

- 3. Farmer P, Kim YJ, Kleinman A, Basilico M. Introduction: A biosocial approach to global health. In: Farmer P, Kim YJ, Kleinman A, Basilico M, editor. Reimagining global health: An introduction. Berkeley and Los Angeles, CA: University of California Press; 2013. p. 1–14.

- View Article

- PubMed/NCBI

- Google Scholar

- 11. National Institute of Mental Health. Helping children and adolescents cope with violence and disasters: What parents can do. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; 2013.

- 12. Trauma and violence. 2019 [Last updated on August 2]. [Internet]. Available from: https://www.samhsa.gov/trauma-violence .

- 13. Evidence-based practice in health. 2020 Dec 21. [cited 21 December 2020]. [Internet]. Available from https://canberra.libguides.com/c.php?g=599346&p=4149722#s-lg-box-12888072 .

- 14. Covidence systematic review software, Veritas Health Innovation. 2019 [Last updated on February 4]. [Internet]. Available at: https://www.covidence.org/ .

- 15. Tufanaru C, Munn Z, Aromataris E, Campbell J, Hopp L. Chapter 3: Systematic reviews of effectiveness. In: Aromataris E MZ, editor. Joanna Briggs Institute Reviewer’s Manual . The Joanna Briggs Institute; 2017.

- Open access

- Published: 14 September 2022

Trauma-informed care in the UK: where are we? A qualitative study of health policies and professional perspectives

- Elizabeth Emsley 1 ,

- Joshua Smith 1 ,

- David Martin 2 &

- Natalia V. Lewis 3

BMC Health Services Research volume 22 , Article number: 1164 ( 2022 ) Cite this article

13k Accesses

9 Citations

15 Altmetric

Metrics details

Trauma-informed (TI) approach is a framework for a system change intervention that transforms the organizational culture and practices to address the high prevalence and impact of trauma on patients and healthcare professionals, and prevents re-traumatization in healthcare services. Review of TI approaches in primary and community mental healthcare identified limited evidence for its effectiveness in the UK, however it is endorsed in various policies. This study aimed to investigate the UK-specific context through exploring how TI approaches are represented in health policies, and how they are understood and implemented by policy makers and healthcare professionals.

A qualitative study comprising of a document analysis of UK health policies followed by semi-structured interviews with key informants with direct experience of developing and implementing TI approaches. We used the Ready Extract Analyse Distil (READ) approach to guide policy document review, and the framework method to analyse data.

We analysed 24 documents and interviewed 11 professionals from healthcare organizations and local authorities. TI approach was included in national, regional and local policies, however, there was no UK- or NHS-wide strategy or legislation, nor funding commitment. Although documents and interviews provided differing interpretations of TI care, they were aligned in describing the integration of TI principles at the system level, contextual tailoring to each organization, and addressing varied challenges within health systems. TI care in the UK has had piecemeal implementation, with a nation-wide strategy and leadership visible in Scotland and Wales and more disjointed implementation in England. Professionals wanted enhanced coordination between organizations and regions. We identified factors affecting implementation of TI approaches at the level of organization (leadership, service user involvement, organizational culture, resource allocation, competing priorities) and wider context (government support, funding). Professionals had conflicting views on the future of TI approaches, however all agreed that government backing is essential for implementing policies into practice.

Conclusions

A coordinated, more centralized strategy and provision for TI healthcare, increased funding for evaluation, and education through professional networks about evidence-based TI health systems can contribute towards evidence-informed policies and implementation of TI approaches in the UK.

Peer Review reports

Individual, interpersonal and collective trauma is a highly prevalent and costly public health problem [ 1 ]. The WHO World Mental Health Survey identified that 70% of participants had experienced lifetime traumas, including physical violence, intimate partner sexual violence, and trauma related to war [ 2 ]. People experiencing socio-economic disadvantage, women, minoritized ethnic groups, and the LGBTQ + community are disproportionally affected by violence and trauma [ 3 , 4 ]. Adverse childhood experiences (ACEs) are stressful or traumatic events that occur during childhood or adolescence [ 5 ]. In England, a household survey found that nearly half of adults had experienced at least one ACE, including childhood sexual, physical or verbal abuse, as well as household domestic violence and abuse (DVA) [ 6 ]. DVA is considered to be a chronic and cumulative cause of complex trauma [ 7 ]. Up to 29% women and 13% men have experienced DVA in their lifetime, at a cost of £14 billion a year to the UK economy [ 7 , 8 , 9 ].

Cumulative trauma across the lifespan is associated with multiple health consequences [ 10 ]. The links between cumulative adversity from ACEs, DVA and other traumatic experiences are explained within the ecobiodevelopmental framework and the concept of toxic stress [ 11 ]. In a systematic review and meta-analysis of 37 observational studies of health behaviours and adult disease, patients with four or more ACEs were at higher risk of a range of poorer health outcomes including cardiovascular disease and mental ill health, versus those with no ACEs history [ 12 ]. Individuals and families who have experienced violence and trauma seek support from healthcare and other services for the physical, psychological and socioeconomic consequences of trauma [ 1 , 13 ]. In the household survey in England and Wales, adults who had experienced four ACEs were twice as likely to attend their general practice repeatedly, compared with those with no ACEs history, and incidence of health service use rose as the ACEs experiences increased [ 14 ]. In a systematic review 47% of patients in mental health services had experienced physical abuse and 37% had experienced sexual abuse [ 15 ].

If the high prevalence and negative impacts of trauma are not recognised and addressed in healthcare services, there may be negative consequences for patients and healthcare professionals. Patients may not disclose trauma or recognise the impact of trauma on their health [ 16 ]. Patients may also be at risk of re-triggering and re-traumatization, for example by the removal of choice regarding treatment, judgemental responses following a disclosure of abuse, seclusion and restraint [ 17 , 18 , 19 ]. Re-traumatization within health services can affect both patients and members of staff, with the latter experiencing vicarious trauma [ 20 ]. The resulting chronic stress may impact on staff members’ ability to empathise and support others [ 21 ]. Many healthcare staff themselves have lived experience of trauma. A recent systematic review of healthcare professionals’ own experience of DVA, reported a pooled lifetime prevalence of 31.3% (95% CI [24.7%, 38.7%] [ 22 ].

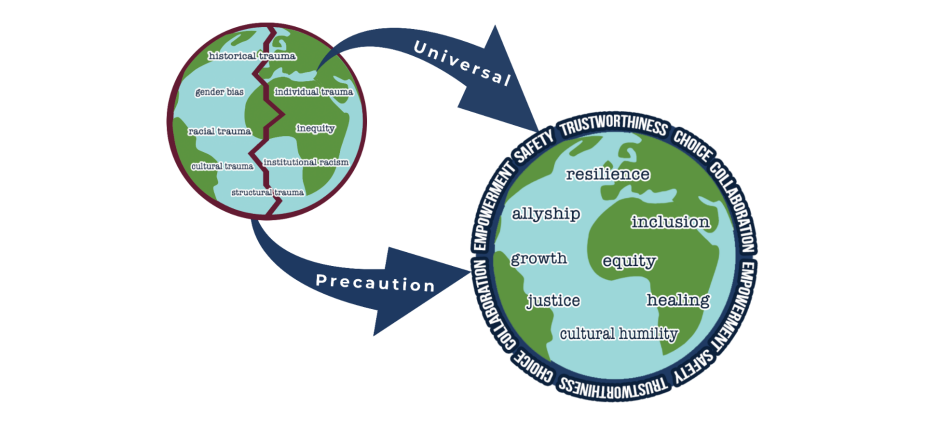

Over last 20 years, several frameworks for a trauma-informed (TI) approach at the health systems level have been developed [ 13 , 17 , 23 , 24 , 25 , 26 , 27 , 28 ]. These frameworks aim to prevent re-traumatization in healthcare services and mitigate the high prevalence and negative effects of violence and trauma on patients and healthcare professionals. A TI approach (synonyms TI care, TI service system) starts from the assumption that every patient and healthcare professional could potentially have been affected by trauma [ 13 ]. By realising and recognising these experiences and their impacts, we can respond by providing services in a trauma-informed way to improve healthcare experience and outcomes for both patients and staff. The process of becoming a TI system is guided by key principles of safety, trust, peer support, collaboration, empowerment and cultural sensitivity [ 13 ]. The most cited frameworks for a system-level TI approach are those by Harris and Fallot [ 29 ], and the US Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) [ 13 ]. These frameworks highlight that it is necessary to, firstly, change organizational culture and environments (organizational domain) and then change clinical practices (clinical domain) by incorporating the four TI assumptions and six TI principles throughout the ten implementation domains within a health system [ 13 ] . Other authors proposed similar constructs for the framework of TI approach, often using slightly differing terminology [ 29 , 30 ]. The authors consistently highlighted that the framework of TI approach is not a protocol but rather high-level guidance applicable to any human service system and should be tailored to the organizational and wider contexts. The process of becoming a TI system is described as a transformation journey rather than a one-off activity.

Despite a 20-year history of the TI approach framework, several reviews have found limited evidence for their effectiveness in health systems, with most studies conducted in North America and only one qualitative study in the UK [ 31 , 32 , 33 ]. Despite little evidence of acceptability, effectiveness, and cost effectiveness in the UK context, policies and guidelines at national, regional and organisational levels recommend implementing TI approaches in healthcare organisations and systems. It is important to understand how TI approaches are being introduced into policy documents, and how these policies are being interpreted and applied within UK healthcare. This study aims to understand the UK-specific context for implementing a TI approach in healthcare by exploring:

How are TI approaches represented in UK health policies?

How are TI approaches understood by policy makers and healthcare professionals?

How are TI approaches implemented in the UK?

This study of UK policy and practice will help us understand what TI approaches mean for policy makers and professionals to inform future UK-specific policy and TI approaches in healthcare.

To answer our research questions, and consider perspectives from different standpoints, we conducted a multi-method qualitative study comprised of a document analysis of UK health policies followed by semi-structured interviews with key informants. Document analysis explored how TI approaches are represented in UK health policy while interviews explored professional views on how they are understood and implemented. We used the Ready Extract Analyse Distil (READ) approach [ 34 ], to guide the review of health policies and the framework method [ 35 ], to analyse data. The framework method is suitable for applied health research conducted by multi-disciplinary teams with varied experiences of qualitative analysis.

Data collection

Data collection occurred between October 2020 and June 2021, with researchers and interviewees based in remote settings due to social distancing restrictions during the COVID-19 pandemic. Sample size was informed by the concept of information power [ 36 ], and restricted by the available funding and a tight timeline.

Document search

We defined policy as ‘a statement of the government’s position, intent or action’ [ 37 ], and considered this definition at the level of a nation, local authority or organization. Two researchers (EE, NVL) identified key policy and related contextual documents, which provided background information on TI approaches. We identified documents through: (i) searches for peer reviewed and grey literature in our earlier systematic review on TI primary care and community mental healthcare [ 31 ], (ii) snowballing of references from included documents, (iii) signposting by interview participants and experts in the field of TI care. Researchers retrieved documents meeting the inclusion criteria: adult healthcare, UK-focus and discussion of TI approaches. We excluded documents on child healthcare, trauma-specific interventions and non-UK focus.

Qualitative interviews

We conducted virtual semi-structured interviews with professionals at decision making levels who have direct experience of developing and implementing TI approaches in the UK healthcare system. We agreed to recruit up to 10 professionals from national and local governments and healthcare organisations. Researchers sent an expression of interest letter via email and Twitter to: (i) individuals and professional networks of policy makers, (ii) authors of included policy documents, (iii) individuals recommended by interview participants. Interested individuals contacted study researchers who checked their eligibility, sent participant information leaflets, answered questions, and arranged interviews with those eligible and willing to proceed. Interviews were conducted over the Zoom video call platform. Researchers obtained verbal informed consent, asked demographic questions, and followed a flexible topic guide to ensure primary issues were covered during all interviews but allowing participants to introduce unanticipated issues. The topic guide explored participant experiences of developing and implementing TI approaches and their views on how TI approaches have come to be represented in policy and implementation (Additional file 1 ). The interviews were audio-recorded with consent, professionally transcribed verbatim, and anonymised.

Data analysis started alongside data collection, to help refine and guide further data collection [ 35 ]. We followed the four-step READ approach to document review in health policy research: 1) ‘Ready your materials’ which involves agreeing the type and quantity of documents to analyse, 2) ‘Extract data’ whereby key document information such as basic data and concepts are organized, 3)’Analyse data’ when data is interpreted and findings are developed, 4) ‘Distil your findings’ which involves assessing whether there is sufficient data to answer the research question and findings are refined into a narrative [ 34 ].

In step one, two researchers (EE, NVL) agreed to use purposive sampling to gather 24 documents representing a broad range of document categories including primary legislation, parliamentary documents, NHS and Public Health England strategy and planning documents, service-user perspectives, evaluation reports, and guidance on ‘how to do’ TI approach [ 38 ]. EE ordered included documents chronologically. In step two, EE read and re-read all included documents and used a customized Excel form to extract data on document title, authors, year, source, objectives, target audience, focus, key messages, referenced evidence, policies/guidelines, and recommendations. During data extraction, researchers made notes about how each document answered the following questions: What is TI care? TI care for whom? Why TI care? EE and NVL met regularly to discuss preliminary ideas for analysis.

In step three, we imported all included documents and interview transcripts into NVivo R project and applied the framework method [ 35 ]. To address variability in definitions and terminology regarding TI approaches, we included key concepts from the well-known SAMHSA system-level framework [ 13 ], as a basis for our coding frame, for example the six TI principles. First, all researchers read four documents and two interview transcripts and independently manually coded text relevant to our research questions using a combination of inductive and deductive coding [ 39 ]. Deductive coding helped to identify concepts related to TI care, even if the document itself did not specifically use the “trauma-informed” term. The researchers then met to compare initial thematic codes and agree on a ‘working analytical framework’ which was imported into NVivo and applied to the documents and interviews transcripts. We refined the framework by adding and merging thematic codes identified subsequently, ran matrix coding queries by data sub-sets (documents, interviews), and combined codes into final analytical themes that answered our research questions. During the analysis stage, researchers met bi-weekly to finalise the dataset, develop and refine coding frame and themes. We wrote reflective diaries and analytical notes and discussed how our clinical backgrounds in general practice and psychiatry, and varied experiences of qualitative research, could have influenced the analysis.

In step four, we stopped document review when we reached the pre-specified number of documents and discussed common findings. First, we illustrated how TI approaches have developed in the UK over time by creating an integrated timeline with document publication dates, the years when interview participants began working in this area, and broader contextual factors from national news and related media. Then we integrated findings from the analysis of documents and interviews through three iterative cycles of developing final analytical themes cutting across documents and interviews. Researchers produced written accounts of the themes, and tables with illustrative quotes that explained how TI approaches have been represented in policy documents, understood, and implemented in the UK.

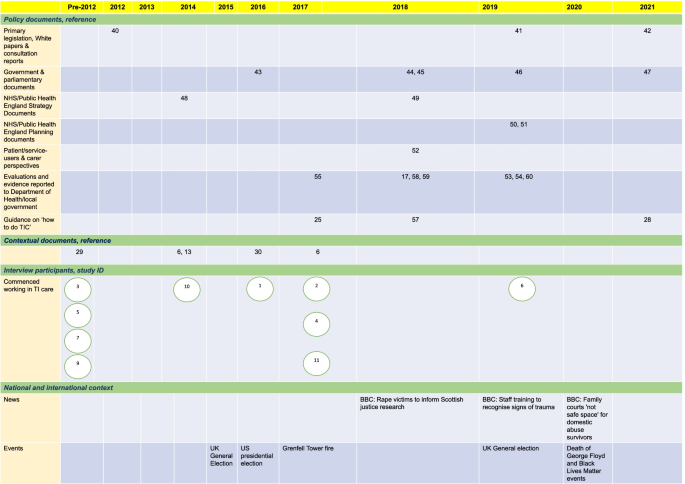

Policy documents

We identified 50 documents and selected 24 policy documents at national, local, and organizational levels. The remaining 26 documents provided context and a background on TI approaches. The documents included were published over nine years (2012–2021) and considered all UK nations, multiple sectors, government policy and service-user voices. The documents either mentioned a TI approach or discussed related concepts such as a patient choice and safety of services (Table 1 ).

Mirroring the historical development of TI approaches from mental health services [ 13 , 29 ], across both documents and interviews, mental health was the most referenced sector ( n = 24), followed by women’s health ( n = 11), healthcare for rough-sleepers ( n = 7), primary care ( n = 4) and major incident management ( n = 1). The level of application of the TI approach varied from one organization [ 55 ], to a public health board [ 59 ], to NHS-wide [ 48 , 50 ]. The geographic coverage of policy documents ranged from UK wide ( n = 10) to regional application ( n = 24). Scotland emerged as a leading region with the TI knowledge and skills framework for the Scottish Workforce [ 25 ].

The timeline of TI approaches and related concepts in the UK showed a steady growth between 2012 and 2021 with parallel developments from top-down and bottom-up (Fig. 1 ).

An integrated timeline of how TI approaches have developed in the UK. Document publication dates, the years when interview participants began working in this area, and broader contextual factors from national news and related media are captured. The number/s in each cell correspond to a document reference [ 6 , 13 , 17 , 25 , 28 , 29 , 30 , 40 , 41 , 42 , 43 , 44 , 45 , 46 , 47 , 48 , 49 , 50 , 51 , 52 , 53 , 54 , 55 , 57 , 58 , 59 , 60 ]

We identified few documents prior to 2012, with the Health and Social Care Act published in 2012. Although the Act did not specifically use the term TI care, it discussed related concepts of a greater voice for patients, enabling patient choice and safety of services. We found a noticeable clustering of documents in 2018 and 2019. Potential contributions could be the release of key contextual documents such as the US SAMHSA guidance and the National ACEs Study in the preceding years [ 13 , 14 ]. Other possible reasons could be the high-profile MeToo and Black Lives Matter movements and tragedies like Grenfell fire. Relevant news articles, including calls for rape victim support and professional training on trauma, came to the fore in 2018–2021. These events and activities have brought the issues of trauma, vulnerable populations, intersectionality, and racial justice to the foreground and may have helped achieve a focus on TI approaches as a responsive system-level framework.

In total, 21 professionals expressed interest, 2 did not have direct experience of TI approach at the system level, 8 did not respond by the deadline, 11 provided consent and were interviewed. Interviews lasted between 32 and 68 min (mean 52 min). We achieved a maximum variation sample representing diversity of gender (4 men, 7 women), organizations (public, private, third sector), professional role (frontline to leadership positions), and direct experience of developing and/or implementing TI approaches in healthcare (from 2 to 25 years). Most participants developed and implemented TI approaches in England, at the level of organizations and local authorities (Table 2 ).

Three out of ten interview participants had been involved in developing and implementing TI approaches prior to the release of the first document in 2012, with the rest becoming involved in 2017, just prior to the clustering of documents in 2018 and 2019 indicating a pivotal wave of popularity of the TI approach framework at this time. Participants explained that their clinical practice facilitated interest in the topic.

Our framework analysis has produced three analytical themes with seven sub-themes:

How TI approaches are represented in UK health policies

How ti approaches are understood, ti care as different from other practices, ti care as a contextually tailored organizational approach.

TI care as a remedy to challenges;

How TI approaches are implemented

Piecemeal implementation and a need for a shared vision, factors that facilitated or hindered implementation, the evidence-policy gap, the future of ti care in the uk.

We found that the TI approach is referenced in government initiatives and included in policies at a national level, as well as in NHS and non-NHS organizations, local authorities, and devolved nations; however, there was no dedicated strategy or a position statement, nor was there an agreed terminology and framework, or a robust evidence base in the UK. Despite growing endorsement of TI approaches in policy documents (Fig. 1 ), positive statements at the national and NHS level were not backed up with legislation, guidance, funding commitment, and resource allocation.

We found divergent interpretations of a TI approach versus other concepts related to trauma, such as ACEs, psychologically informed environments and standard good clinical practice. One participant unified concepts such as TI care, ACEs and psychologically informed environments in recognising past traumatic experiences. Another participant detached the terms ACEs and TI care, reflecting that ACEs have become well known in research whereas a TI approach is a pragmatic way of supporting those who have experienced trauma. All documents and most participants clearly differentiated between a TI approach at the system level and standalone TI practices (e.g., routine enquiry about ACEs, one-off training about trauma). However, some participants considered standalone TI practices to be a TI approach. Documents and most interviewees differentiated TI approach from a good clinical practice by incorporation of the TI assumptions and principles [ 25 ].

In line with the SAMHSA guidance [ 13 ], document and interview data showed that the framework of a TI approach needs to be tailored to the organizational and wider context. Policy documents advised organizations to clarify what TI care means for them, and that application of the framework should depend on the needs of service users and organisations [ 25 , 28 , 52 , 54 , 59 , 60 ]. Several documents suggested that this organizational tailoring should be informed by service-users through co-production and co-design of services [ 17 , 28 , 49 , 52 , 53 , 54 , 55 , 60 , 61 ].

TI care as a remedy to challenges

In all policy documents and in nine interviews, TI approaches were presented as a remedy to a variety of problems within health systems. Sixteen of twenty-five documents justified a TI approach as a way for addressing the high prevalence and negative impact of violence and trauma on patients, with eleven documents considering its impact on staff. The growing international evidence base for the impact of psychological trauma and the need for service response was used in documents and interviews to justify TI approaches as a pragmatic solution to these concerns. However, the documents and interview participants justified the need for TI care by citing US and Welsh epidemiological studies on ACEs, DVA and patient accounts of being re-traumatized in services. We found no references to intervention studies that demonstrated effectiveness, cost-effectiveness, or acceptability of TI approaches in the UK.

In the NHS Long Term Plan, TI care was also identified as a component of a new model of integrated care [ 50 ]. A TI approach has also been presented as a solution to addressing the collective trauma of the COVID-19 pandemic for patients and staff [ 62 ].

Interviewees confirmed the piecemeal implementation of TI approaches in the UK and felt that a shared national vision would be beneficial. Participants agreed that the implementation of TI approaches varied across the UK, with Scotland having more strategic coordinated implementation (additional file 2 , quote 1). We found that different regions and organizations reinvented the TI approach wheel, with interviewees expressing a need for national coordination. Participants expressed the need for adequate allocated resources and a more unified approach across organizations and sectors as a solution to the patchy implementation in England (additional file 2 , quote 2). They gave examples of the bottom-up networking initiatives driven by experts in TI care who created opportunities for sharing best practice and resources for implementing TI approaches. Participants cited a UK-wide Trauma Informed Community of Action and local TI care working groups.

One participant from England suggested that whilst the SAMSHA definition of TI approach was widely cited, they did not feel there was an agreed set of components and activities for implementing the framework in practice. This participant felt that a consensus on shared practice standards was a necessary next step for TI care in the UK.

At the organization level, some participants felt high level leadership support was needed, and if lacking is a barrier to implementing a TI approach. To achieve effective implementation leaders with power and those with passion were felt to be important. The concept of organizational champions garnered support when “ champions act as influencers and their credibility within services adds to the potential for buy-in from other staff ”, fostering sustainable change [ 53 ]. One participant warned against a reliance on top-down leadership, explaining that when a senior leader leaves an organization’s priorities can change. The participant also felt that change driven from the top-down, might lead to resistance from front-line staff (additional file 2 , quote 3). Some interviewees reaffirmed the view that people with lived experience should be involved in leading implementation of TI approaches (additional file 2 , quote 4).

Some interviewees felt that passionate individuals alone cannot create effective change without support at the organization level (additional file 2 , quote 5). Collective responsibility and organizational commitment were highlighted as an essential factor to support individuals with passion. In contrast, unsupportive organizational culture and high-pressure environments was perceived as a barrier (additional file 2 , quote 6). One document cited scarcity of resources and low staff morale, as well as a resistance to new initiatives and upheaval [ 52 ]. Competing demands and opportunity costs were also raised (additional file 2 , quote 7).

At the wider context level, documents highlighted the value of political support capable of influencing practice nationally [ 17 ]. Some interviewees explained disconnected and decentralized implementation of TI approaches across the UK by a shortage of political will and leadership in the central UK government, compared with those of the devolved administrations in Scotland and Wales (additional file 2 , quote 8). Proposed explanations included smaller territories, populations and governments, and “ more of a left-leaning social conscience politics” (Participant 3). Another interviewee called for a united parliamentary leadership recognised by government and capable of influencing policy.

Inadequate funding and commissioning of services was also described as a barrier, partly explaining regional differences in implementation of TI care (additional file 2 , quote 9). The COVID-19 pandemic was perceived as a barrier that contributed to the backlog of initiatives and work in the pipeline (additional file 2 , quote 10).

UK policies on implementation of TI approaches were not supported by UK-specific, methodologically robust, evidence for effectiveness, cost effectiveness and acceptability. Participants explained the policy-evidence gap by citing methodological challenges of evaluating system-level transformation and a need for commitment from commissioners and funders (additional file 2 , quote 11). In addition, participants who developed and implemented TI approaches in their organizations and regions did not have the capacity to evaluate their initiatives and disseminate the findings (additional file 2 , quote 12).

Participants had differing views on the future of TI care in the UK, although most agreed on its permanency. Some interviewees felt that TI approaches have already gained a critical momentum in the UK. In contrast to comments about TI care as a passing trend or ‘buzzword’ in the absence of in depth understanding, several interviewees voiced confidence that TI approach is here to stay, and will evolve, being incorporated into policy as well as being adopted more widely. Others were less optimistic and were concerned that insufficient political backing means policy endorsement will not translate to meaningful practice change.

Some participants thought that TI care should become a mandatory consideration with stronger central policy or monitoring by national watchdogs. They felt that the support of additional nation-wide regulatory measures could be beneficial. In contrast, some interviewees showed scepticism, fearing the creation of further ‘box-ticking’ measures. They feared that efforts to police or monitor providers could create a burden of empty bureaucracy without improving practice (additional file 2 , quote 13).

Our document analysis of health policies and interviews with professionals found differing representation, understanding, and implementation of TI approaches in the UK with wide variations between geographical areas, services, and individual professionals. Cross-sectoral endorsement of TI approaches in policies was not supported by high-level legislation or funding, and a UK-specific evidence base. Despite divergent and conflicting interpretations of TI approaches, the common understanding was that it differs from other practices by integrating TI principles at the organisational level and it should be tailored to the organization and wider contexts. It can also address NHS problems from integrated care to post-COVID recovery. We found more centralized implementation of TI approaches in Scotland and Wales versus piecemeal implementation in England. The implementation of TI approaches in England was driven from the bottom-up by passionate dedicated leaders at the level of organization or local authority, who called for more coordinated working supported by the UK government and NHS leaders. We identified factors that facilitated or hindered implementation of TI approaches at the level of organization (leadership, service user involvement, organizational culture, resource allocation, competing priorities) and wider context (government support, funding). The evidence-policy gap in TI care implementation can be explained by limited funding and evaluation capacity. Professionals had differing views on the future of TI approaches, however all agreed that without political backing at the government level, policy endorsement will not translate into meaningful implementation.

Our finding of a marked difference in the landscape of TI approaches in healthcare systems between the devolved nations, with evidence of a unified national strategy emerging in Scotland and Wales and notably absent in England could have several explanations. These include smaller territories, populations, and governments in devolved nations, with clear buy-in from government-level leadership in Scotland. Our analysis highlighted the initiatives of local decision-makers in England who have developed and implemented TI approaches in their own organizations and local authorities. The absence of a national strategy in England contributed to the piecemeal implementation, with some regions leading the way, and others silent. As local TI leads have been left to ‘find their own way’, they may not always have been aware of similar initiatives in other organizations and regions. A proposed solution was bottom-up initiatives aiming to bring the local TI leads together to share resources and good practice. This finding indicates the need for a leader on TI approaches within or linked to the UK government who can support and strengthen the bottom-up initiatives.

Another important finding is confirmation of the evidence-policy gap, with proposed reasons emerging in the analysis. Interview participants explained an absence of UK evidence on the effectiveness of TI approaches by a need for more interest from commissioners and funders, as well as a lack of physical and methodological capacity to evaluate system-level TI approaches. The former can be resolved through funding calls and comprehensive, transparent evaluation. The latter can be addressed by funding evaluations and raising awareness regarding available methodologies and tools for evaluating TI system change interventions [ 32 , 33 ].

Our finding of differing understanding of TI-approaches is in line with prior literature [ 63 ]. We found that some participants interpreted standalone TI practices (e.g., ACEs enquiry, one-off training about TI care) as a TI approach. Such interpretations are not supported by evidence. Authors of the ACEs study explained that the ACEs score is not a diagnostic tool, therefore care should be taken if used as part of community-wide screening, with rigorous evaluation of its use [ 64 ]. Recent reviews also found limited evidence on outcomes from routine enquiry, recommending further research [ 65 , 66 ]. Several systematic reviews demonstrated that standalone awareness raising did not result in change in behaviour and practices among healthcare professionals [ 67 , 68 ].

These misunderstandings can be explained by the conceptual mutability of a TI approach framework, lack of awareness about existing frameworks, and a need for coordinated working led by experts in TI approaches. The evidence of emerging working groups and UK-wide professional networks on TI care is promising. However, these initiatives require adequate funding and coordination to sustain momentum and develop further. These professional networks can become the platform for education about evidence-based TI approaches contributing to increasing value and reducing waste in research and implementation in this field.

This study is methodologically robust with perspectives drawn from UK policy documents and professionals, who have direct experience of developing and implementing TI approaches. Data analysis occurred alongside data collection, to help refine and guide further data collection. The limitations include no professional informants from devolved nations and no participants at the level of UK government. Due to time and funding restrictions, we could only recruit 11 professionals and did not interview patients including those with lived experience of trauma. Our small sample size could have resulted in underrepresentation of views of some stakeholders. Future research should recruit informants from these groups to draw a complete picture of the landscape of TI approaches in the UK.

Although health policies endorse implementation of TI approaches in the UK, they do not provide specific legislation, strategy or funding and are not supported by evidence of effectiveness. Understanding and implementation of TI approaches varies between regions, organizations, and individual professionals; however, all agree that if implemented at the system level and contextually tailored, TI approaches can mitigate varied problems withing NHS. The implementation of TI approaches in the UK is driven by local experts in TI care. A coordinated, more centralized strategy and enhanced provisioning for TI healthcare, including increased funding for evaluation and education through TI professional networks, can contribute towards evidence-informed policies and implementation of TI approaches in the UK.

Availability of data and materials

Data are available at the University of Bristol data repository, data.bris, at https://doi.org/10.5523/bris.2awc5pqkavac12d6jm1qp9wetm .

For reference: Lewis, N. (2022): TAPCARE policy review study. https://doi.org/10.5523/bris.2awc5pqkavac12d6jm1qp9wetm

All methods were performed in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations as detailed here: https://www.biomedcentral.com/getpublished/editorial-policies#research+involving+human+embryos%2C+gametes%2C+and+stem+cells .

Abbreviations

Adverse childhood experiences

Coronavirus disease

Domestic violence and abuse

National Health Service

Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration

Trauma-informed

United Kingdom

United States of America

Magruder KM, McLaughlin KA, Elmore Borbon DL. Trauma is a public health issue. Eur J Psychotraumatol. 2017;8(1):1375338.

Article Google Scholar

Kessler RC, et al. Trauma and PTSD in the who world mental health surveys. Eur J Psychotraumatol. 2017;8(sup5):1353383.

Hatch SL, Dohrenwend BP. Distribution of traumatic and other stressful life events by race/ethnicity, gender, SES and age: a review of the research. Am J Community Psychol. 2007;40(3–4):313–32.

Ellis AE. Providing trauma-informed affirmative care: Introduction to special issue on evidence-based relationship variables in working with affectional and gender minorities. Pract Innov. 2020;5(3):179–88.

Prevention, C.f.D.C.a., Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACEs): preventing early trauma to improve adult health, in CDC Vital Signs. 2019.

Bellis MA, et al. National household survey of adverse childhood experiences and their relationship with resilience to health-harming behaviors in England. BMC Med. 2014;12:72.

Scottish government. NHS Education for Scotland, S.G. Domestic abuse- and trauma-informed practice: companion document.

Statistics, O.f.N., Percentage of adults aged 16 to 74 years who were victims of domestic abuse in the last year, by ethnic group: year ending March 2018 to year ending March 2020, in Crime Survey for England and Wales (CSEW). 2020.

Rhys Oliver, B.A., Stephen Roe, Miriam Wlasny The economic and social costs of domestic abuse. 2019. 77.

Sacchi L, Merzhvynska M, Augsburger M. Effects of cumulative trauma load on long-term trajectories of life satisfaction and health in a population-based study. BMC Public Health. 2020;20(1):1612.

Shonkoff JP, Garner AS. The lifelong effects of early childhood adversity and toxic stress. Pediatrics. 2012;129(1):e232–46.

Hughes K, et al. The effect of multiple adverse childhood experiences on health: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Public Health. 2017;2(8):e356–66.

Administration, S.A.a.M.H.S., SAMHSA’s Concept of Trauma and Guidance for a Trauma-Informed Approach . Department of Health and Human Services USA, 2014: p. 27.

Bellis M, et al. The impact of adverse childhood experiences on health service use across the life course using a retrospective cohort study. J Health Serv Res Policy. 2017;22(3):168–77.

Mauritz MW, et al. Prevalence of interpersonal trauma exposure and trauma-related disorders in severe mental illness . Eur J Psychotraumatol. 2013;4:4.

Heron RL, Eisma MC. Barriers and facilitators of disclosing domestic violence to the healthcare service: a systematic review of qualitative research. Health Soc Care Community. 2021;29(3):612–30.

Department of Health and Social Care, A. The Women’s Mental Health Taskforce: Final report. 2018. 73.

Sweeney A, et al. A paradigm shift: relationships in trauma-informed mental health services. BJPsych advances. 2018;24(5):319–33.

Schippert ACSP, Grov EK, Bjørnnes AK. Uncovering re-traumatization experiences of torture survivors in somatic health care: A qualitative systematic review. PLoS ONE. 2021;16(2):e0246074–e0246074.

Article CAS Google Scholar

Jimenez RR, et al. Vicarious trauma in mental health care providers. J Interprofessional Educ Pract. 2021;24:100451.

Sweeney A, et al. Trauma-informed mental healthcare in the UK: what is it and how can we further its development? Ment Health Rev J. 2016;21:174–92.

Dheensa, S., et al., Healthcare Professionals' Own Experiences of Domestic Violence and Abuse: A Meta-Analysis of Prevalence and Systematic Review of Risk Markers and Consequences. Trauma Violence Abuse, 2022: p. 15248380211061771.

Harris M, F.R., Using trauma theory to design service systems. San Francisco. CA: Jossey-Bass; 2001.

Google Scholar

S, H. Medical Directors' Recommendations on Trauma-informed Care for Persons with Serious Mental Illness. 2018. 1–20.

Scottish government. NHS Education for Scotland, S.G. Transforming psychological trauma: a knowledge and skills framework for the Scottish workforce. 2017. 124.

Government of Canada. Canada, G.o. Trauma and violence-informed approaches to policy and practice. 2018.

Kimberg L, W.M., Trauma and trauma-informed care. New York. NY: Springer, Berlin Heidelberg; 2019.

Clare Law, L.W., Mickey Sperlich, Julie Taylor, A good practice guide to support implementation of trauma-informed care in the perinatal period . 2021: p. 42.

Harris M, Fallot RD. Envisioning a trauma-informed service system: a vital paradigm shift. New Dir Ment Health Serv. 2001;89:3–22.

Bowen EA, Murshid NS. Trauma-informed social policy: a conceptual framework for policy analysis and advocacy. Am J Public Health. 2016;106(2):223–9.