- Affiliate Program

- UNITED STATES

- 台灣 (TAIWAN)

- TÜRKIYE (TURKEY)

- Academic Editing Services

- - Research Paper

- - Journal Manuscript

- - Dissertation

- - College & University Assignments

- Admissions Editing Services

- - Application Essay

- - Personal Statement

- - Recommendation Letter

- - Cover Letter

- - CV/Resume

- Business Editing Services

- - Business Documents

- - Report & Brochure

- - Website & Blog

- Writer Editing Services

- - Script & Screenplay

- Our Editors

- Client Reviews

- Editing & Proofreading Prices

- Wordvice Points

- Partner Discount

- Plagiarism Checker

- APA Citation Generator

- MLA Citation Generator

- Chicago Citation Generator

- Vancouver Citation Generator

- - APA Style

- - MLA Style

- - Chicago Style

- - Vancouver Style

- Writing & Editing Guide

- Academic Resources

- Admissions Resources

How to Make a Literature Review in Research (RRL Example)

What is an RRL in a research paper?

A relevant review of the literature (RRL) is an objective, concise, critical summary of published research literature relevant to a topic being researched in an article. In an RRL, you discuss knowledge and findings from existing literature relevant to your study topic. If there are conflicts or gaps in existing literature, you can also discuss these in your review, as well as how you will confront these missing elements or resolve these issues in your study.

To complete an RRL, you first need to collect relevant literature; this can include online and offline sources. Save all of your applicable resources as you will need to include them in your paper. When looking through these sources, take notes and identify concepts of each source to describe in the review of the literature.

A good RRL does NOT:

A literature review does not simply reference and list all of the material you have cited in your paper.

- Presenting material that is not directly relevant to your study will distract and frustrate the reader and make them lose sight of the purpose of your study.

- Starting a literature review with “A number of scholars have studied the relationship between X and Y” and simply listing who has studied the topic and what each scholar concluded is not going to strengthen your paper.

A good RRL DOES:

- Present a brief typology that orders articles and books into groups to help readers focus on unresolved debates, inconsistencies, tensions, and new questions about a research topic.

- Summarize the most relevant and important aspects of the scientific literature related to your area of research

- Synthesize what has been done in this area of research and by whom, highlight what previous research indicates about a topic, and identify potential gaps and areas of disagreement in the field

- Give the reader an understanding of the background of the field and show which studies are important—and highlight errors in previous studies

How long is a review of the literature for a research paper?

The length of a review of the literature depends on its purpose and target readership and can vary significantly in scope and depth. In a dissertation, thesis, or standalone review of literature, it is usually a full chapter of the text (at least 20 pages). Whereas, a standard research article or school assignment literature review section could only be a few paragraphs in the Introduction section .

Building Your Literature Review Bookshelf

One way to conceive of a literature review is to think about writing it as you would build a bookshelf. You don’t need to cut each piece by yourself from scratch. Rather, you can take the pieces that other researchers have cut out and put them together to build a framework on which to hang your own “books”—that is, your own study methods, results, and conclusions.

What Makes a Good Literature Review?

The contents of a literature review (RRL) are determined by many factors, including its precise purpose in the article, the degree of consensus with a given theory or tension between competing theories, the length of the article, the number of previous studies existing in the given field, etc. The following are some of the most important elements that a literature review provides.

Historical background for your research

Analyze what has been written about your field of research to highlight what is new and significant in your study—or how the analysis itself contributes to the understanding of this field, even in a small way. Providing a historical background also demonstrates to other researchers and journal editors your competency in discussing theoretical concepts. You should also make sure to understand how to paraphrase scientific literature to avoid plagiarism in your work.

The current context of your research

Discuss central (or peripheral) questions, issues, and debates in the field. Because a field is constantly being updated by new work, you can show where your research fits into this context and explain developments and trends in research.

A discussion of relevant theories and concepts

Theories and concepts should provide the foundation for your research. For example, if you are researching the relationship between ecological environments and human populations, provide models and theories that focus on specific aspects of this connection to contextualize your study. If your study asks a question concerning sustainability, mention a theory or model that underpins this concept. If it concerns invasive species, choose material that is focused in this direction.

Definitions of relevant terminology

In the natural sciences, the meaning of terms is relatively straightforward and consistent. But if you present a term that is obscure or context-specific, you should define the meaning of the term in the Introduction section (if you are introducing a study) or in the summary of the literature being reviewed.

Description of related relevant research

Include a description of related research that shows how your work expands or challenges earlier studies or fills in gaps in previous work. You can use your literature review as evidence of what works, what doesn’t, and what is missing in the field.

Supporting evidence for a practical problem or issue your research is addressing that demonstrates its importance: Referencing related research establishes your area of research as reputable and shows you are building upon previous work that other researchers have deemed significant.

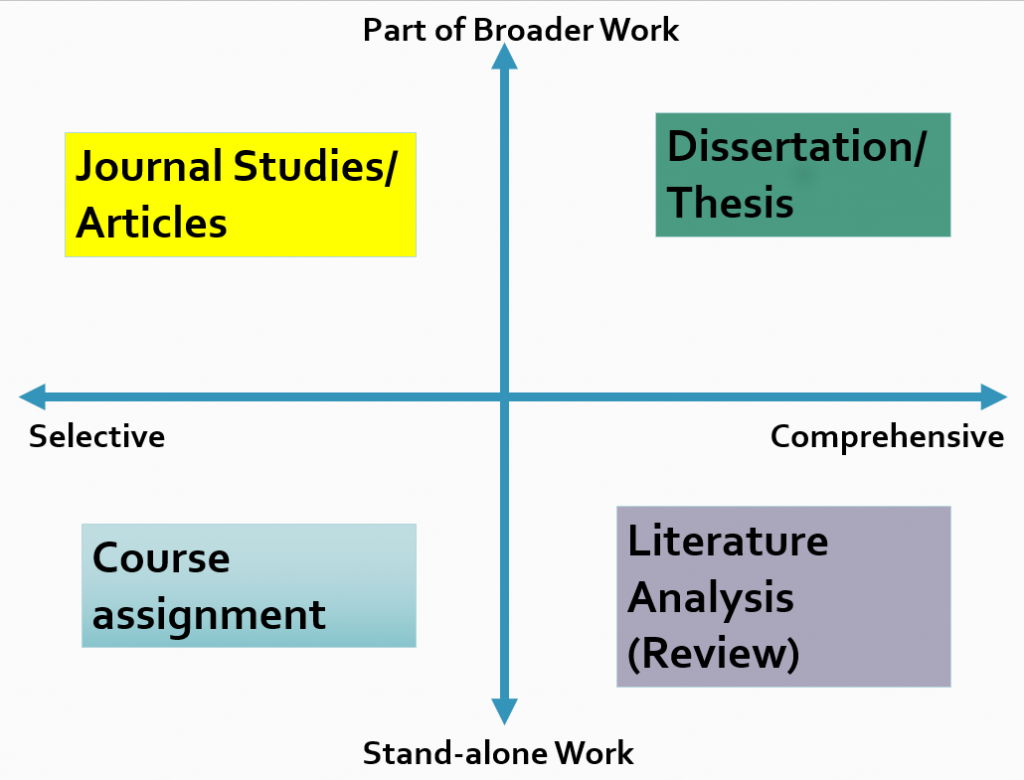

Types of Literature Reviews

Literature reviews can differ in structure, length, amount, and breadth of content included. They can range from selective (a very narrow area of research or only a single work) to comprehensive (a larger amount or range of works). They can also be part of a larger work or stand on their own.

- A course assignment is an example of a selective, stand-alone work. It focuses on a small segment of the literature on a topic and makes up an entire work on its own.

- The literature review in a dissertation or thesis is both comprehensive and helps make up a larger work.

- A majority of journal articles start with a selective literature review to provide context for the research reported in the study; such a literature review is usually included in the Introduction section (but it can also follow the presentation of the results in the Discussion section ).

- Some literature reviews are both comprehensive and stand as a separate work—in this case, the entire article analyzes the literature on a given topic.

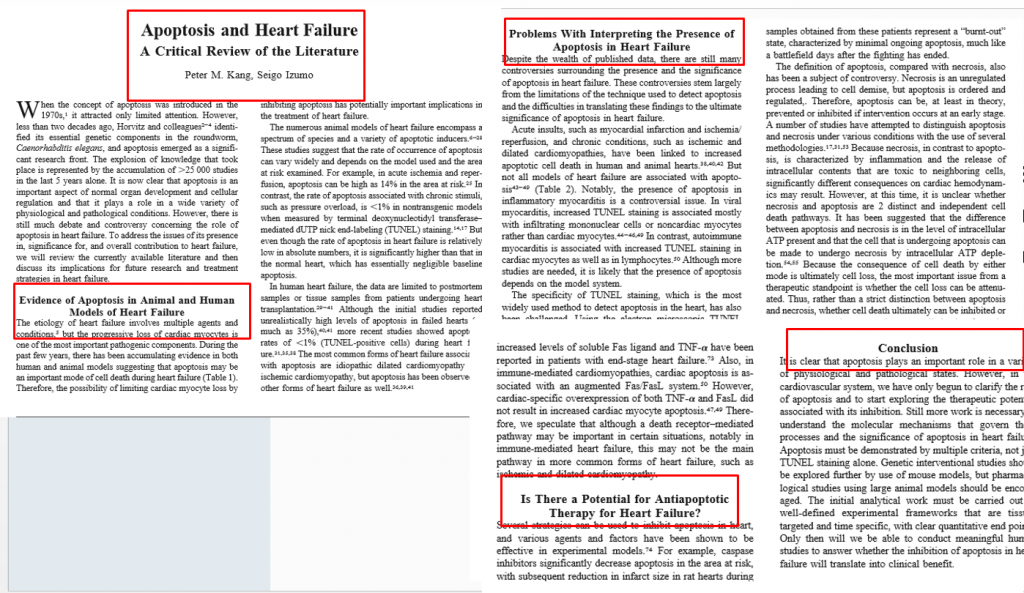

Literature Reviews Found in Academic Journals

The two types of literature reviews commonly found in journals are those introducing research articles (studies and surveys) and stand-alone literature analyses. They can differ in their scope, length, and specific purpose.

Literature reviews introducing research articles

The literature review found at the beginning of a journal article is used to introduce research related to the specific study and is found in the Introduction section, usually near the end. It is shorter than a stand-alone review because it must be limited to very specific studies and theories that are directly relevant to the current study. Its purpose is to set research precedence and provide support for the study’s theory, methods, results, and/or conclusions. Not all research articles contain an explicit review of the literature, but most do, whether it is a discrete section or indistinguishable from the rest of the Introduction.

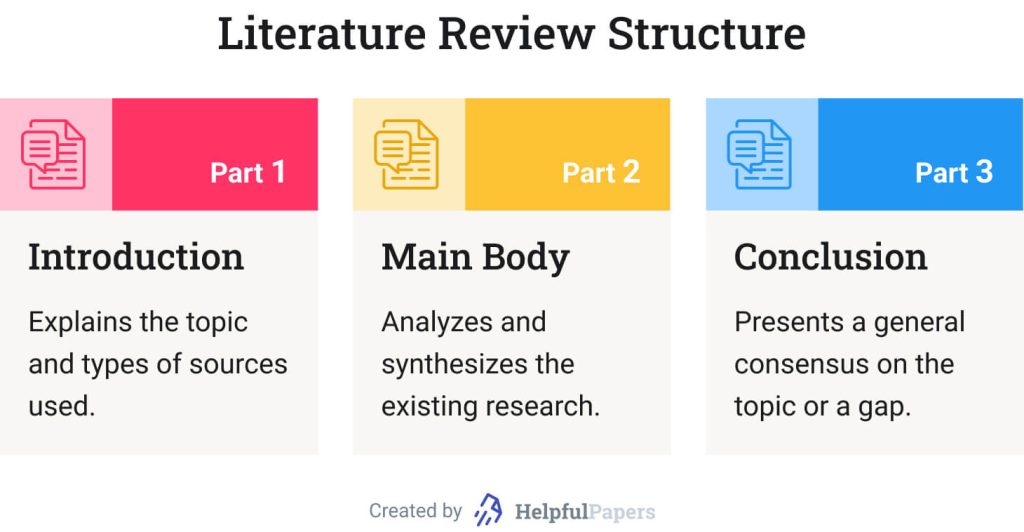

How to structure a literature review for an article

When writing a literature review as part of an introduction to a study, simply follow the structure of the Introduction and move from the general to the specific—presenting the broadest background information about a topic first and then moving to specific studies that support your rationale , finally leading to your hypothesis statement. Such a literature review is often indistinguishable from the Introduction itself—the literature is INTRODUCING the background and defining the gaps your study aims to fill.

The stand-alone literature review

The literature review published as a stand-alone article presents and analyzes as many of the important publications in an area of study as possible to provide background information and context for a current area of research or a study. Stand-alone reviews are an excellent resource for researchers when they are first searching for the most relevant information on an area of study.

Such literature reviews are generally a bit broader in scope and can extend further back in time. This means that sometimes a scientific literature review can be highly theoretical, in addition to focusing on specific methods and outcomes of previous studies. In addition, all sections of such a “review article” refer to existing literature rather than describing the results of the authors’ own study.

In addition, this type of literature review is usually much longer than the literature review introducing a study. At the end of the review follows a conclusion that once again explicitly ties all of the cited works together to show how this analysis is itself a contribution to the literature. While not absolutely necessary, such articles often include the terms “Literature Review” or “Review of the Literature” in the title. Whether or not that is necessary or appropriate can also depend on the specific author instructions of the target journal. Have a look at this article for more input on how to compile a stand-alone review article that is insightful and helpful for other researchers in your field.

How to Write a Literature Review in 6 Steps

So how do authors turn a network of articles into a coherent review of relevant literature?

Writing a literature review is not usually a linear process—authors often go back and check the literature while reformulating their ideas or making adjustments to their study. Sometimes new findings are published before a study is completed and need to be incorporated into the current work. This also means you will not be writing the literature review at any one time, but constantly working on it before, during, and after your study is complete.

Here are some steps that will help you begin and follow through on your literature review.

Step 1: Choose a topic to write about—focus on and explore this topic.

Choose a topic that you are familiar with and highly interested in analyzing; a topic your intended readers and researchers will find interesting and useful; and a topic that is current, well-established in the field, and about which there has been sufficient research conducted for a review. This will help you find the “sweet spot” for what to focus on.

Step 2: Research and collect all the scholarly information on the topic that might be pertinent to your study.

This includes scholarly articles, books, conventions, conferences, dissertations, and theses—these and any other academic work related to your area of study is called “the literature.”

Step 3: Analyze the network of information that extends or responds to the major works in your area; select the material that is most useful.

Use thought maps and charts to identify intersections in the research and to outline important categories; select the material that will be most useful to your review.

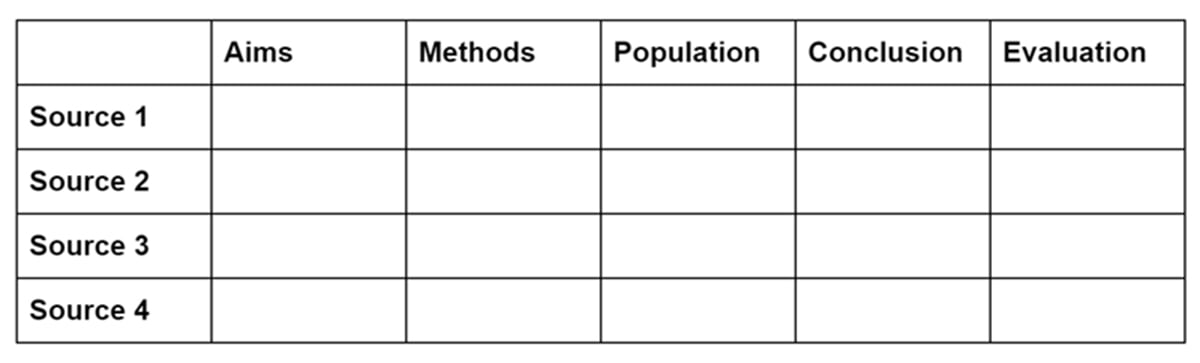

Step 4: Describe and summarize each article—provide the essential information of the article that pertains to your study.

Determine 2-3 important concepts (depending on the length of your article) that are discussed in the literature; take notes about all of the important aspects of this study relevant to the topic being reviewed.

For example, in a given study, perhaps some of the main concepts are X, Y, and Z. Note these concepts and then write a brief summary about how the article incorporates them. In reviews that introduce a study, these can be relatively short. In stand-alone reviews, there may be significantly more texts and more concepts.

Step 5: Demonstrate how these concepts in the literature relate to what you discovered in your study or how the literature connects the concepts or topics being discussed.

In a literature review intro for an article, this information might include a summary of the results or methods of previous studies that correspond to and/or confirm those sections in your own study. For a stand-alone literature review, this may mean highlighting the concepts in each article and showing how they strengthen a hypothesis or show a pattern.

Discuss unaddressed issues in previous studies. These studies that are missing something you address are important to include in your literature review. In addition, those works whose theories and conclusions directly support your findings will be valuable to review here.

Step 6: Identify relationships in the literature and develop and connect your own ideas to them.

This is essentially the same as step 5 but focused on the connections between the literature and the current study or guiding concepts or arguments of the paper, not only on the connections between the works themselves.

Your hypothesis, argument, or guiding concept is the “golden thread” that will ultimately tie the works together and provide readers with specific insights they didn’t have before reading your literature review. Make sure you know where to put the research question , hypothesis, or statement of the problem in your research paper so that you guide your readers logically and naturally from your introduction of earlier work and evidence to the conclusions you want them to draw from the bigger picture.

Your literature review will not only cover publications on your topics but will include your own ideas and contributions. By following these steps you will be telling the specific story that sets the background and shows the significance of your research and you can turn a network of related works into a focused review of the literature.

Literature Review (RRL) Examples

Because creating sample literature reviews would take too long and not properly capture the nuances and detailed information needed for a good review, we have included some links to different types of literature reviews below. You can find links to more literature reviews in these categories by visiting the TUS Library’s website . Sample literature reviews as part of an article, dissertation, or thesis:

- Critical Thinking and Transferability: A Review of the Literature (Gwendolyn Reece)

- Building Customer Loyalty: A Customer Experience Based Approach in a Tourism Context (Martina Donnelly)

Sample stand-alone literature reviews

- Literature Review on Attitudes towards Disability (National Disability Authority)

- The Effects of Communication Styles on Marital Satisfaction (Hannah Yager)

Additional Literature Review Format Guidelines

In addition to the content guidelines above, authors also need to check which style guidelines to use ( APA , Chicago, MLA, etc.) and what specific rules the target journal might have for how to structure such articles or how many studies to include—such information can usually be found on the journals’ “Guide for Authors” pages. Additionally, use one of the four Wordvice citation generators below, choosing the citation style needed for your paper:

Wordvice Writing and Academic Editing Resources

Finally, after you have finished drafting your literature review, be sure to receive professional proofreading services , including paper editing for your academic work. A competent proofreader who understands academic writing conventions and the specific style guides used by academic journals will ensure that your paper is ready for publication in your target journal.

See our academic resources for further advice on references in your paper , how to write an abstract , how to write a research paper title, how to impress the editor of your target journal with a perfect cover letter , and dozens of other research writing and publication topics.

- USC Libraries

- Research Guides

Organizing Your Social Sciences Research Paper

- 5. The Literature Review

- Purpose of Guide

- Design Flaws to Avoid

- Independent and Dependent Variables

- Glossary of Research Terms

- Reading Research Effectively

- Narrowing a Topic Idea

- Broadening a Topic Idea

- Extending the Timeliness of a Topic Idea

- Academic Writing Style

- Applying Critical Thinking

- Choosing a Title

- Making an Outline

- Paragraph Development

- Research Process Video Series

- Executive Summary

- The C.A.R.S. Model

- Background Information

- The Research Problem/Question

- Theoretical Framework

- Citation Tracking

- Content Alert Services

- Evaluating Sources

- Primary Sources

- Secondary Sources

- Tiertiary Sources

- Scholarly vs. Popular Publications

- Qualitative Methods

- Quantitative Methods

- Insiderness

- Using Non-Textual Elements

- Limitations of the Study

- Common Grammar Mistakes

- Writing Concisely

- Avoiding Plagiarism

- Footnotes or Endnotes?

- Further Readings

- Generative AI and Writing

- USC Libraries Tutorials and Other Guides

- Bibliography

A literature review surveys prior research published in books, scholarly articles, and any other sources relevant to a particular issue, area of research, or theory, and by so doing, provides a description, summary, and critical evaluation of these works in relation to the research problem being investigated. Literature reviews are designed to provide an overview of sources you have used in researching a particular topic and to demonstrate to your readers how your research fits within existing scholarship about the topic.

Fink, Arlene. Conducting Research Literature Reviews: From the Internet to Paper . Fourth edition. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE, 2014.

Importance of a Good Literature Review

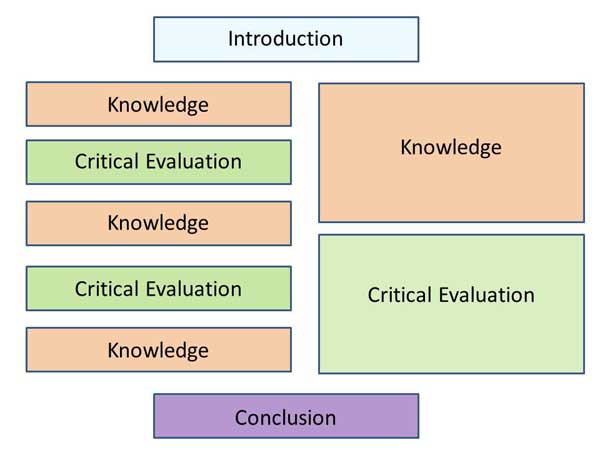

A literature review may consist of simply a summary of key sources, but in the social sciences, a literature review usually has an organizational pattern and combines both summary and synthesis, often within specific conceptual categories . A summary is a recap of the important information of the source, but a synthesis is a re-organization, or a reshuffling, of that information in a way that informs how you are planning to investigate a research problem. The analytical features of a literature review might:

- Give a new interpretation of old material or combine new with old interpretations,

- Trace the intellectual progression of the field, including major debates,

- Depending on the situation, evaluate the sources and advise the reader on the most pertinent or relevant research, or

- Usually in the conclusion of a literature review, identify where gaps exist in how a problem has been researched to date.

Given this, the purpose of a literature review is to:

- Place each work in the context of its contribution to understanding the research problem being studied.

- Describe the relationship of each work to the others under consideration.

- Identify new ways to interpret prior research.

- Reveal any gaps that exist in the literature.

- Resolve conflicts amongst seemingly contradictory previous studies.

- Identify areas of prior scholarship to prevent duplication of effort.

- Point the way in fulfilling a need for additional research.

- Locate your own research within the context of existing literature [very important].

Fink, Arlene. Conducting Research Literature Reviews: From the Internet to Paper. 2nd ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage, 2005; Hart, Chris. Doing a Literature Review: Releasing the Social Science Research Imagination . Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, 1998; Jesson, Jill. Doing Your Literature Review: Traditional and Systematic Techniques . Los Angeles, CA: SAGE, 2011; Knopf, Jeffrey W. "Doing a Literature Review." PS: Political Science and Politics 39 (January 2006): 127-132; Ridley, Diana. The Literature Review: A Step-by-Step Guide for Students . 2nd ed. Los Angeles, CA: SAGE, 2012.

Types of Literature Reviews

It is important to think of knowledge in a given field as consisting of three layers. First, there are the primary studies that researchers conduct and publish. Second are the reviews of those studies that summarize and offer new interpretations built from and often extending beyond the primary studies. Third, there are the perceptions, conclusions, opinion, and interpretations that are shared informally among scholars that become part of the body of epistemological traditions within the field.

In composing a literature review, it is important to note that it is often this third layer of knowledge that is cited as "true" even though it often has only a loose relationship to the primary studies and secondary literature reviews. Given this, while literature reviews are designed to provide an overview and synthesis of pertinent sources you have explored, there are a number of approaches you could adopt depending upon the type of analysis underpinning your study.

Argumentative Review This form examines literature selectively in order to support or refute an argument, deeply embedded assumption, or philosophical problem already established in the literature. The purpose is to develop a body of literature that establishes a contrarian viewpoint. Given the value-laden nature of some social science research [e.g., educational reform; immigration control], argumentative approaches to analyzing the literature can be a legitimate and important form of discourse. However, note that they can also introduce problems of bias when they are used to make summary claims of the sort found in systematic reviews [see below].

Integrative Review Considered a form of research that reviews, critiques, and synthesizes representative literature on a topic in an integrated way such that new frameworks and perspectives on the topic are generated. The body of literature includes all studies that address related or identical hypotheses or research problems. A well-done integrative review meets the same standards as primary research in regard to clarity, rigor, and replication. This is the most common form of review in the social sciences.

Historical Review Few things rest in isolation from historical precedent. Historical literature reviews focus on examining research throughout a period of time, often starting with the first time an issue, concept, theory, phenomena emerged in the literature, then tracing its evolution within the scholarship of a discipline. The purpose is to place research in a historical context to show familiarity with state-of-the-art developments and to identify the likely directions for future research.

Methodological Review A review does not always focus on what someone said [findings], but how they came about saying what they say [method of analysis]. Reviewing methods of analysis provides a framework of understanding at different levels [i.e. those of theory, substantive fields, research approaches, and data collection and analysis techniques], how researchers draw upon a wide variety of knowledge ranging from the conceptual level to practical documents for use in fieldwork in the areas of ontological and epistemological consideration, quantitative and qualitative integration, sampling, interviewing, data collection, and data analysis. This approach helps highlight ethical issues which you should be aware of and consider as you go through your own study.

Systematic Review This form consists of an overview of existing evidence pertinent to a clearly formulated research question, which uses pre-specified and standardized methods to identify and critically appraise relevant research, and to collect, report, and analyze data from the studies that are included in the review. The goal is to deliberately document, critically evaluate, and summarize scientifically all of the research about a clearly defined research problem . Typically it focuses on a very specific empirical question, often posed in a cause-and-effect form, such as "To what extent does A contribute to B?" This type of literature review is primarily applied to examining prior research studies in clinical medicine and allied health fields, but it is increasingly being used in the social sciences.

Theoretical Review The purpose of this form is to examine the corpus of theory that has accumulated in regard to an issue, concept, theory, phenomena. The theoretical literature review helps to establish what theories already exist, the relationships between them, to what degree the existing theories have been investigated, and to develop new hypotheses to be tested. Often this form is used to help establish a lack of appropriate theories or reveal that current theories are inadequate for explaining new or emerging research problems. The unit of analysis can focus on a theoretical concept or a whole theory or framework.

NOTE : Most often the literature review will incorporate some combination of types. For example, a review that examines literature supporting or refuting an argument, assumption, or philosophical problem related to the research problem will also need to include writing supported by sources that establish the history of these arguments in the literature.

Baumeister, Roy F. and Mark R. Leary. "Writing Narrative Literature Reviews." Review of General Psychology 1 (September 1997): 311-320; Mark R. Fink, Arlene. Conducting Research Literature Reviews: From the Internet to Paper . 2nd ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage, 2005; Hart, Chris. Doing a Literature Review: Releasing the Social Science Research Imagination . Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, 1998; Kennedy, Mary M. "Defining a Literature." Educational Researcher 36 (April 2007): 139-147; Petticrew, Mark and Helen Roberts. Systematic Reviews in the Social Sciences: A Practical Guide . Malden, MA: Blackwell Publishers, 2006; Torracro, Richard. "Writing Integrative Literature Reviews: Guidelines and Examples." Human Resource Development Review 4 (September 2005): 356-367; Rocco, Tonette S. and Maria S. Plakhotnik. "Literature Reviews, Conceptual Frameworks, and Theoretical Frameworks: Terms, Functions, and Distinctions." Human Ressource Development Review 8 (March 2008): 120-130; Sutton, Anthea. Systematic Approaches to a Successful Literature Review . Los Angeles, CA: Sage Publications, 2016.

Structure and Writing Style

I. Thinking About Your Literature Review

The structure of a literature review should include the following in support of understanding the research problem :

- An overview of the subject, issue, or theory under consideration, along with the objectives of the literature review,

- Division of works under review into themes or categories [e.g. works that support a particular position, those against, and those offering alternative approaches entirely],

- An explanation of how each work is similar to and how it varies from the others,

- Conclusions as to which pieces are best considered in their argument, are most convincing of their opinions, and make the greatest contribution to the understanding and development of their area of research.

The critical evaluation of each work should consider :

- Provenance -- what are the author's credentials? Are the author's arguments supported by evidence [e.g. primary historical material, case studies, narratives, statistics, recent scientific findings]?

- Methodology -- were the techniques used to identify, gather, and analyze the data appropriate to addressing the research problem? Was the sample size appropriate? Were the results effectively interpreted and reported?

- Objectivity -- is the author's perspective even-handed or prejudicial? Is contrary data considered or is certain pertinent information ignored to prove the author's point?

- Persuasiveness -- which of the author's theses are most convincing or least convincing?

- Validity -- are the author's arguments and conclusions convincing? Does the work ultimately contribute in any significant way to an understanding of the subject?

II. Development of the Literature Review

Four Basic Stages of Writing 1. Problem formulation -- which topic or field is being examined and what are its component issues? 2. Literature search -- finding materials relevant to the subject being explored. 3. Data evaluation -- determining which literature makes a significant contribution to the understanding of the topic. 4. Analysis and interpretation -- discussing the findings and conclusions of pertinent literature.

Consider the following issues before writing the literature review: Clarify If your assignment is not specific about what form your literature review should take, seek clarification from your professor by asking these questions: 1. Roughly how many sources would be appropriate to include? 2. What types of sources should I review (books, journal articles, websites; scholarly versus popular sources)? 3. Should I summarize, synthesize, or critique sources by discussing a common theme or issue? 4. Should I evaluate the sources in any way beyond evaluating how they relate to understanding the research problem? 5. Should I provide subheadings and other background information, such as definitions and/or a history? Find Models Use the exercise of reviewing the literature to examine how authors in your discipline or area of interest have composed their literature review sections. Read them to get a sense of the types of themes you might want to look for in your own research or to identify ways to organize your final review. The bibliography or reference section of sources you've already read, such as required readings in the course syllabus, are also excellent entry points into your own research. Narrow the Topic The narrower your topic, the easier it will be to limit the number of sources you need to read in order to obtain a good survey of relevant resources. Your professor will probably not expect you to read everything that's available about the topic, but you'll make the act of reviewing easier if you first limit scope of the research problem. A good strategy is to begin by searching the USC Libraries Catalog for recent books about the topic and review the table of contents for chapters that focuses on specific issues. You can also review the indexes of books to find references to specific issues that can serve as the focus of your research. For example, a book surveying the history of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict may include a chapter on the role Egypt has played in mediating the conflict, or look in the index for the pages where Egypt is mentioned in the text. Consider Whether Your Sources are Current Some disciplines require that you use information that is as current as possible. This is particularly true in disciplines in medicine and the sciences where research conducted becomes obsolete very quickly as new discoveries are made. However, when writing a review in the social sciences, a survey of the history of the literature may be required. In other words, a complete understanding the research problem requires you to deliberately examine how knowledge and perspectives have changed over time. Sort through other current bibliographies or literature reviews in the field to get a sense of what your discipline expects. You can also use this method to explore what is considered by scholars to be a "hot topic" and what is not.

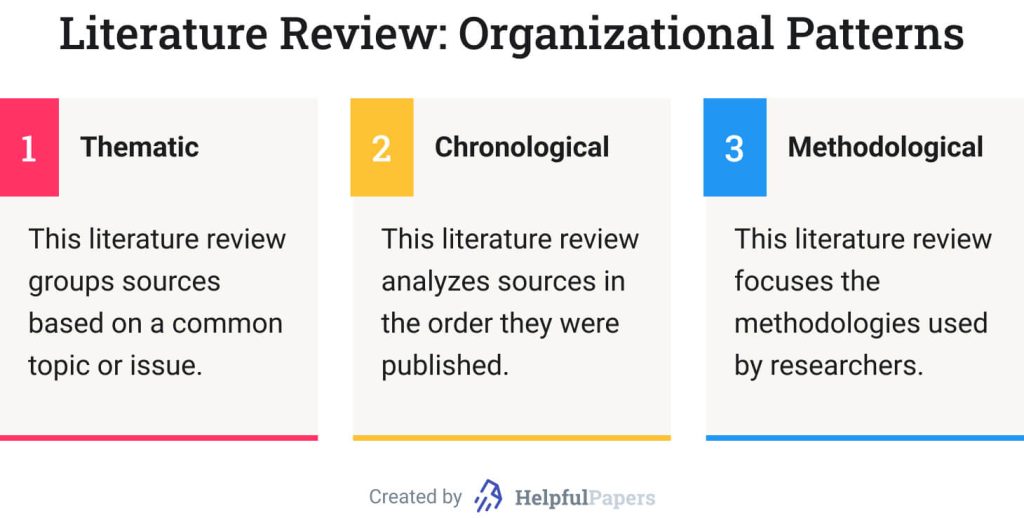

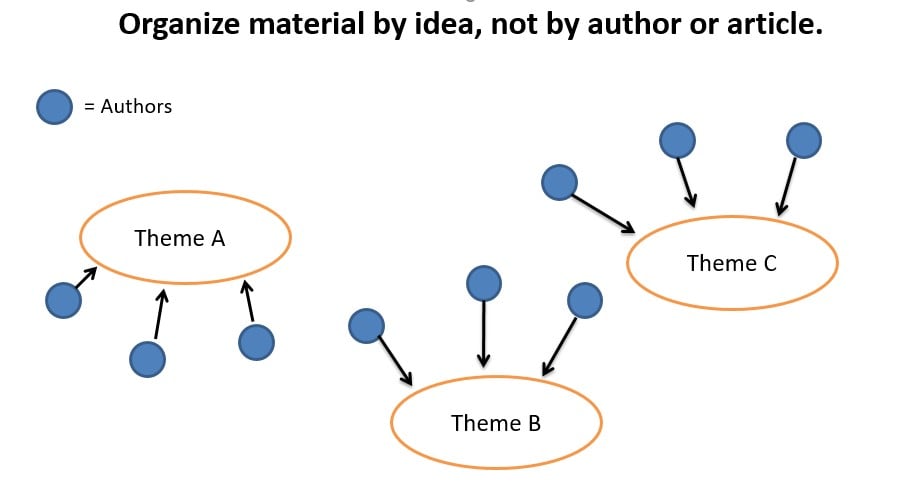

III. Ways to Organize Your Literature Review

Chronology of Events If your review follows the chronological method, you could write about the materials according to when they were published. This approach should only be followed if a clear path of research building on previous research can be identified and that these trends follow a clear chronological order of development. For example, a literature review that focuses on continuing research about the emergence of German economic power after the fall of the Soviet Union. By Publication Order your sources by publication chronology, then, only if the order demonstrates a more important trend. For instance, you could order a review of literature on environmental studies of brown fields if the progression revealed, for example, a change in the soil collection practices of the researchers who wrote and/or conducted the studies. Thematic [“conceptual categories”] A thematic literature review is the most common approach to summarizing prior research in the social and behavioral sciences. Thematic reviews are organized around a topic or issue, rather than the progression of time, although the progression of time may still be incorporated into a thematic review. For example, a review of the Internet’s impact on American presidential politics could focus on the development of online political satire. While the study focuses on one topic, the Internet’s impact on American presidential politics, it would still be organized chronologically reflecting technological developments in media. The difference in this example between a "chronological" and a "thematic" approach is what is emphasized the most: themes related to the role of the Internet in presidential politics. Note that more authentic thematic reviews tend to break away from chronological order. A review organized in this manner would shift between time periods within each section according to the point being made. Methodological A methodological approach focuses on the methods utilized by the researcher. For the Internet in American presidential politics project, one methodological approach would be to look at cultural differences between the portrayal of American presidents on American, British, and French websites. Or the review might focus on the fundraising impact of the Internet on a particular political party. A methodological scope will influence either the types of documents in the review or the way in which these documents are discussed.

Other Sections of Your Literature Review Once you've decided on the organizational method for your literature review, the sections you need to include in the paper should be easy to figure out because they arise from your organizational strategy. In other words, a chronological review would have subsections for each vital time period; a thematic review would have subtopics based upon factors that relate to the theme or issue. However, sometimes you may need to add additional sections that are necessary for your study, but do not fit in the organizational strategy of the body. What other sections you include in the body is up to you. However, only include what is necessary for the reader to locate your study within the larger scholarship about the research problem.

Here are examples of other sections, usually in the form of a single paragraph, you may need to include depending on the type of review you write:

- Current Situation : Information necessary to understand the current topic or focus of the literature review.

- Sources Used : Describes the methods and resources [e.g., databases] you used to identify the literature you reviewed.

- History : The chronological progression of the field, the research literature, or an idea that is necessary to understand the literature review, if the body of the literature review is not already a chronology.

- Selection Methods : Criteria you used to select (and perhaps exclude) sources in your literature review. For instance, you might explain that your review includes only peer-reviewed [i.e., scholarly] sources.

- Standards : Description of the way in which you present your information.

- Questions for Further Research : What questions about the field has the review sparked? How will you further your research as a result of the review?

IV. Writing Your Literature Review

Once you've settled on how to organize your literature review, you're ready to write each section. When writing your review, keep in mind these issues.

Use Evidence A literature review section is, in this sense, just like any other academic research paper. Your interpretation of the available sources must be backed up with evidence [citations] that demonstrates that what you are saying is valid. Be Selective Select only the most important points in each source to highlight in the review. The type of information you choose to mention should relate directly to the research problem, whether it is thematic, methodological, or chronological. Related items that provide additional information, but that are not key to understanding the research problem, can be included in a list of further readings . Use Quotes Sparingly Some short quotes are appropriate if you want to emphasize a point, or if what an author stated cannot be easily paraphrased. Sometimes you may need to quote certain terminology that was coined by the author, is not common knowledge, or taken directly from the study. Do not use extensive quotes as a substitute for using your own words in reviewing the literature. Summarize and Synthesize Remember to summarize and synthesize your sources within each thematic paragraph as well as throughout the review. Recapitulate important features of a research study, but then synthesize it by rephrasing the study's significance and relating it to your own work and the work of others. Keep Your Own Voice While the literature review presents others' ideas, your voice [the writer's] should remain front and center. For example, weave references to other sources into what you are writing but maintain your own voice by starting and ending the paragraph with your own ideas and wording. Use Caution When Paraphrasing When paraphrasing a source that is not your own, be sure to represent the author's information or opinions accurately and in your own words. Even when paraphrasing an author’s work, you still must provide a citation to that work.

V. Common Mistakes to Avoid

These are the most common mistakes made in reviewing social science research literature.

- Sources in your literature review do not clearly relate to the research problem;

- You do not take sufficient time to define and identify the most relevant sources to use in the literature review related to the research problem;

- Relies exclusively on secondary analytical sources rather than including relevant primary research studies or data;

- Uncritically accepts another researcher's findings and interpretations as valid, rather than examining critically all aspects of the research design and analysis;

- Does not describe the search procedures that were used in identifying the literature to review;

- Reports isolated statistical results rather than synthesizing them in chi-squared or meta-analytic methods; and,

- Only includes research that validates assumptions and does not consider contrary findings and alternative interpretations found in the literature.

Cook, Kathleen E. and Elise Murowchick. “Do Literature Review Skills Transfer from One Course to Another?” Psychology Learning and Teaching 13 (March 2014): 3-11; Fink, Arlene. Conducting Research Literature Reviews: From the Internet to Paper . 2nd ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage, 2005; Hart, Chris. Doing a Literature Review: Releasing the Social Science Research Imagination . Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, 1998; Jesson, Jill. Doing Your Literature Review: Traditional and Systematic Techniques . London: SAGE, 2011; Literature Review Handout. Online Writing Center. Liberty University; Literature Reviews. The Writing Center. University of North Carolina; Onwuegbuzie, Anthony J. and Rebecca Frels. Seven Steps to a Comprehensive Literature Review: A Multimodal and Cultural Approach . Los Angeles, CA: SAGE, 2016; Ridley, Diana. The Literature Review: A Step-by-Step Guide for Students . 2nd ed. Los Angeles, CA: SAGE, 2012; Randolph, Justus J. “A Guide to Writing the Dissertation Literature Review." Practical Assessment, Research, and Evaluation. vol. 14, June 2009; Sutton, Anthea. Systematic Approaches to a Successful Literature Review . Los Angeles, CA: Sage Publications, 2016; Taylor, Dena. The Literature Review: A Few Tips On Conducting It. University College Writing Centre. University of Toronto; Writing a Literature Review. Academic Skills Centre. University of Canberra.

Writing Tip

Break Out of Your Disciplinary Box!

Thinking interdisciplinarily about a research problem can be a rewarding exercise in applying new ideas, theories, or concepts to an old problem. For example, what might cultural anthropologists say about the continuing conflict in the Middle East? In what ways might geographers view the need for better distribution of social service agencies in large cities than how social workers might study the issue? You don’t want to substitute a thorough review of core research literature in your discipline for studies conducted in other fields of study. However, particularly in the social sciences, thinking about research problems from multiple vectors is a key strategy for finding new solutions to a problem or gaining a new perspective. Consult with a librarian about identifying research databases in other disciplines; almost every field of study has at least one comprehensive database devoted to indexing its research literature.

Frodeman, Robert. The Oxford Handbook of Interdisciplinarity . New York: Oxford University Press, 2010.

Another Writing Tip

Don't Just Review for Content!

While conducting a review of the literature, maximize the time you devote to writing this part of your paper by thinking broadly about what you should be looking for and evaluating. Review not just what scholars are saying, but how are they saying it. Some questions to ask:

- How are they organizing their ideas?

- What methods have they used to study the problem?

- What theories have been used to explain, predict, or understand their research problem?

- What sources have they cited to support their conclusions?

- How have they used non-textual elements [e.g., charts, graphs, figures, etc.] to illustrate key points?

When you begin to write your literature review section, you'll be glad you dug deeper into how the research was designed and constructed because it establishes a means for developing more substantial analysis and interpretation of the research problem.

Hart, Chris. Doing a Literature Review: Releasing the Social Science Research Imagination . Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, 1 998.

Yet Another Writing Tip

When Do I Know I Can Stop Looking and Move On?

Here are several strategies you can utilize to assess whether you've thoroughly reviewed the literature:

- Look for repeating patterns in the research findings . If the same thing is being said, just by different people, then this likely demonstrates that the research problem has hit a conceptual dead end. At this point consider: Does your study extend current research? Does it forge a new path? Or, does is merely add more of the same thing being said?

- Look at sources the authors cite to in their work . If you begin to see the same researchers cited again and again, then this is often an indication that no new ideas have been generated to address the research problem.

- Search Google Scholar to identify who has subsequently cited leading scholars already identified in your literature review [see next sub-tab]. This is called citation tracking and there are a number of sources that can help you identify who has cited whom, particularly scholars from outside of your discipline. Here again, if the same authors are being cited again and again, this may indicate no new literature has been written on the topic.

Onwuegbuzie, Anthony J. and Rebecca Frels. Seven Steps to a Comprehensive Literature Review: A Multimodal and Cultural Approach . Los Angeles, CA: Sage, 2016; Sutton, Anthea. Systematic Approaches to a Successful Literature Review . Los Angeles, CA: Sage Publications, 2016.

- << Previous: Theoretical Framework

- Next: Citation Tracking >>

- Last Updated: May 20, 2024 9:47 AM

- URL: https://libguides.usc.edu/writingguide

Student Academic Success Center

Related work / literature review / research review, download pdf handout: literature reviews, watch video: literature reviews.

A literature review, research review, or related work section compares, contrasts, synthesizes, and provides introspection about the available knowledge for a given topic or field. The two terms are sometimes used interchangeably (as they are here), but while both can refer to a section of a longer work, “literature review” can also describe a stand-alone paper.

When you start writing a literature review, the most straightforward course may be to compile all relevant sources and compare them, perhaps evaluating their strengths and weaknesses. While this is a good place to start, your literature review is incomplete unless it creates something new through these comparisons. Luckily, our resources can help you do this!

With these resources, you’ll learn:

- How to write a literature review that contributes rather than summarizes

- Common mistakes to avoid

- Useful phrases to show agreement and disagreement between sources

Need one-on-one help with your literature review or research article? Schedule an appointment with one of our consultants now!

Schedule an Appointment

Quick Links

- Academic Calendar

- Academic Integrity

- Bias Reporting and Response

- Statement of Assurance

- Documents, Forms, and News [Internal Staff Only]

Other Helpful Departments

- Disability Resources

- Center for Student Diversity & Inclusion

- Graduate Education

- Office of International Education

- University Health Services

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- J Korean Med Sci

- v.37(16); 2022 Apr 25

A Practical Guide to Writing Quantitative and Qualitative Research Questions and Hypotheses in Scholarly Articles

Edward barroga.

1 Department of General Education, Graduate School of Nursing Science, St. Luke’s International University, Tokyo, Japan.

Glafera Janet Matanguihan

2 Department of Biological Sciences, Messiah University, Mechanicsburg, PA, USA.

The development of research questions and the subsequent hypotheses are prerequisites to defining the main research purpose and specific objectives of a study. Consequently, these objectives determine the study design and research outcome. The development of research questions is a process based on knowledge of current trends, cutting-edge studies, and technological advances in the research field. Excellent research questions are focused and require a comprehensive literature search and in-depth understanding of the problem being investigated. Initially, research questions may be written as descriptive questions which could be developed into inferential questions. These questions must be specific and concise to provide a clear foundation for developing hypotheses. Hypotheses are more formal predictions about the research outcomes. These specify the possible results that may or may not be expected regarding the relationship between groups. Thus, research questions and hypotheses clarify the main purpose and specific objectives of the study, which in turn dictate the design of the study, its direction, and outcome. Studies developed from good research questions and hypotheses will have trustworthy outcomes with wide-ranging social and health implications.

INTRODUCTION

Scientific research is usually initiated by posing evidenced-based research questions which are then explicitly restated as hypotheses. 1 , 2 The hypotheses provide directions to guide the study, solutions, explanations, and expected results. 3 , 4 Both research questions and hypotheses are essentially formulated based on conventional theories and real-world processes, which allow the inception of novel studies and the ethical testing of ideas. 5 , 6

It is crucial to have knowledge of both quantitative and qualitative research 2 as both types of research involve writing research questions and hypotheses. 7 However, these crucial elements of research are sometimes overlooked; if not overlooked, then framed without the forethought and meticulous attention it needs. Planning and careful consideration are needed when developing quantitative or qualitative research, particularly when conceptualizing research questions and hypotheses. 4

There is a continuing need to support researchers in the creation of innovative research questions and hypotheses, as well as for journal articles that carefully review these elements. 1 When research questions and hypotheses are not carefully thought of, unethical studies and poor outcomes usually ensue. Carefully formulated research questions and hypotheses define well-founded objectives, which in turn determine the appropriate design, course, and outcome of the study. This article then aims to discuss in detail the various aspects of crafting research questions and hypotheses, with the goal of guiding researchers as they develop their own. Examples from the authors and peer-reviewed scientific articles in the healthcare field are provided to illustrate key points.

DEFINITIONS AND RELATIONSHIP OF RESEARCH QUESTIONS AND HYPOTHESES

A research question is what a study aims to answer after data analysis and interpretation. The answer is written in length in the discussion section of the paper. Thus, the research question gives a preview of the different parts and variables of the study meant to address the problem posed in the research question. 1 An excellent research question clarifies the research writing while facilitating understanding of the research topic, objective, scope, and limitations of the study. 5

On the other hand, a research hypothesis is an educated statement of an expected outcome. This statement is based on background research and current knowledge. 8 , 9 The research hypothesis makes a specific prediction about a new phenomenon 10 or a formal statement on the expected relationship between an independent variable and a dependent variable. 3 , 11 It provides a tentative answer to the research question to be tested or explored. 4

Hypotheses employ reasoning to predict a theory-based outcome. 10 These can also be developed from theories by focusing on components of theories that have not yet been observed. 10 The validity of hypotheses is often based on the testability of the prediction made in a reproducible experiment. 8

Conversely, hypotheses can also be rephrased as research questions. Several hypotheses based on existing theories and knowledge may be needed to answer a research question. Developing ethical research questions and hypotheses creates a research design that has logical relationships among variables. These relationships serve as a solid foundation for the conduct of the study. 4 , 11 Haphazardly constructed research questions can result in poorly formulated hypotheses and improper study designs, leading to unreliable results. Thus, the formulations of relevant research questions and verifiable hypotheses are crucial when beginning research. 12

CHARACTERISTICS OF GOOD RESEARCH QUESTIONS AND HYPOTHESES

Excellent research questions are specific and focused. These integrate collective data and observations to confirm or refute the subsequent hypotheses. Well-constructed hypotheses are based on previous reports and verify the research context. These are realistic, in-depth, sufficiently complex, and reproducible. More importantly, these hypotheses can be addressed and tested. 13

There are several characteristics of well-developed hypotheses. Good hypotheses are 1) empirically testable 7 , 10 , 11 , 13 ; 2) backed by preliminary evidence 9 ; 3) testable by ethical research 7 , 9 ; 4) based on original ideas 9 ; 5) have evidenced-based logical reasoning 10 ; and 6) can be predicted. 11 Good hypotheses can infer ethical and positive implications, indicating the presence of a relationship or effect relevant to the research theme. 7 , 11 These are initially developed from a general theory and branch into specific hypotheses by deductive reasoning. In the absence of a theory to base the hypotheses, inductive reasoning based on specific observations or findings form more general hypotheses. 10

TYPES OF RESEARCH QUESTIONS AND HYPOTHESES

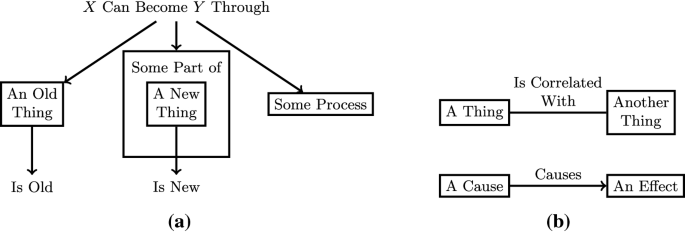

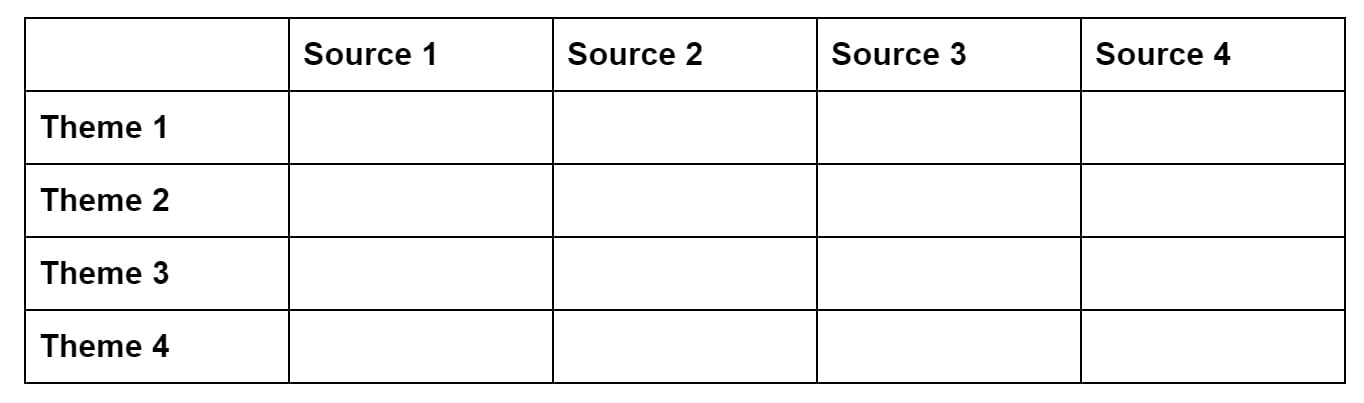

Research questions and hypotheses are developed according to the type of research, which can be broadly classified into quantitative and qualitative research. We provide a summary of the types of research questions and hypotheses under quantitative and qualitative research categories in Table 1 .

Research questions in quantitative research

In quantitative research, research questions inquire about the relationships among variables being investigated and are usually framed at the start of the study. These are precise and typically linked to the subject population, dependent and independent variables, and research design. 1 Research questions may also attempt to describe the behavior of a population in relation to one or more variables, or describe the characteristics of variables to be measured ( descriptive research questions ). 1 , 5 , 14 These questions may also aim to discover differences between groups within the context of an outcome variable ( comparative research questions ), 1 , 5 , 14 or elucidate trends and interactions among variables ( relationship research questions ). 1 , 5 We provide examples of descriptive, comparative, and relationship research questions in quantitative research in Table 2 .

Hypotheses in quantitative research

In quantitative research, hypotheses predict the expected relationships among variables. 15 Relationships among variables that can be predicted include 1) between a single dependent variable and a single independent variable ( simple hypothesis ) or 2) between two or more independent and dependent variables ( complex hypothesis ). 4 , 11 Hypotheses may also specify the expected direction to be followed and imply an intellectual commitment to a particular outcome ( directional hypothesis ) 4 . On the other hand, hypotheses may not predict the exact direction and are used in the absence of a theory, or when findings contradict previous studies ( non-directional hypothesis ). 4 In addition, hypotheses can 1) define interdependency between variables ( associative hypothesis ), 4 2) propose an effect on the dependent variable from manipulation of the independent variable ( causal hypothesis ), 4 3) state a negative relationship between two variables ( null hypothesis ), 4 , 11 , 15 4) replace the working hypothesis if rejected ( alternative hypothesis ), 15 explain the relationship of phenomena to possibly generate a theory ( working hypothesis ), 11 5) involve quantifiable variables that can be tested statistically ( statistical hypothesis ), 11 6) or express a relationship whose interlinks can be verified logically ( logical hypothesis ). 11 We provide examples of simple, complex, directional, non-directional, associative, causal, null, alternative, working, statistical, and logical hypotheses in quantitative research, as well as the definition of quantitative hypothesis-testing research in Table 3 .

Research questions in qualitative research

Unlike research questions in quantitative research, research questions in qualitative research are usually continuously reviewed and reformulated. The central question and associated subquestions are stated more than the hypotheses. 15 The central question broadly explores a complex set of factors surrounding the central phenomenon, aiming to present the varied perspectives of participants. 15

There are varied goals for which qualitative research questions are developed. These questions can function in several ways, such as to 1) identify and describe existing conditions ( contextual research question s); 2) describe a phenomenon ( descriptive research questions ); 3) assess the effectiveness of existing methods, protocols, theories, or procedures ( evaluation research questions ); 4) examine a phenomenon or analyze the reasons or relationships between subjects or phenomena ( explanatory research questions ); or 5) focus on unknown aspects of a particular topic ( exploratory research questions ). 5 In addition, some qualitative research questions provide new ideas for the development of theories and actions ( generative research questions ) or advance specific ideologies of a position ( ideological research questions ). 1 Other qualitative research questions may build on a body of existing literature and become working guidelines ( ethnographic research questions ). Research questions may also be broadly stated without specific reference to the existing literature or a typology of questions ( phenomenological research questions ), may be directed towards generating a theory of some process ( grounded theory questions ), or may address a description of the case and the emerging themes ( qualitative case study questions ). 15 We provide examples of contextual, descriptive, evaluation, explanatory, exploratory, generative, ideological, ethnographic, phenomenological, grounded theory, and qualitative case study research questions in qualitative research in Table 4 , and the definition of qualitative hypothesis-generating research in Table 5 .

Qualitative studies usually pose at least one central research question and several subquestions starting with How or What . These research questions use exploratory verbs such as explore or describe . These also focus on one central phenomenon of interest, and may mention the participants and research site. 15

Hypotheses in qualitative research

Hypotheses in qualitative research are stated in the form of a clear statement concerning the problem to be investigated. Unlike in quantitative research where hypotheses are usually developed to be tested, qualitative research can lead to both hypothesis-testing and hypothesis-generating outcomes. 2 When studies require both quantitative and qualitative research questions, this suggests an integrative process between both research methods wherein a single mixed-methods research question can be developed. 1

FRAMEWORKS FOR DEVELOPING RESEARCH QUESTIONS AND HYPOTHESES

Research questions followed by hypotheses should be developed before the start of the study. 1 , 12 , 14 It is crucial to develop feasible research questions on a topic that is interesting to both the researcher and the scientific community. This can be achieved by a meticulous review of previous and current studies to establish a novel topic. Specific areas are subsequently focused on to generate ethical research questions. The relevance of the research questions is evaluated in terms of clarity of the resulting data, specificity of the methodology, objectivity of the outcome, depth of the research, and impact of the study. 1 , 5 These aspects constitute the FINER criteria (i.e., Feasible, Interesting, Novel, Ethical, and Relevant). 1 Clarity and effectiveness are achieved if research questions meet the FINER criteria. In addition to the FINER criteria, Ratan et al. described focus, complexity, novelty, feasibility, and measurability for evaluating the effectiveness of research questions. 14

The PICOT and PEO frameworks are also used when developing research questions. 1 The following elements are addressed in these frameworks, PICOT: P-population/patients/problem, I-intervention or indicator being studied, C-comparison group, O-outcome of interest, and T-timeframe of the study; PEO: P-population being studied, E-exposure to preexisting conditions, and O-outcome of interest. 1 Research questions are also considered good if these meet the “FINERMAPS” framework: Feasible, Interesting, Novel, Ethical, Relevant, Manageable, Appropriate, Potential value/publishable, and Systematic. 14

As we indicated earlier, research questions and hypotheses that are not carefully formulated result in unethical studies or poor outcomes. To illustrate this, we provide some examples of ambiguous research question and hypotheses that result in unclear and weak research objectives in quantitative research ( Table 6 ) 16 and qualitative research ( Table 7 ) 17 , and how to transform these ambiguous research question(s) and hypothesis(es) into clear and good statements.

a These statements were composed for comparison and illustrative purposes only.

b These statements are direct quotes from Higashihara and Horiuchi. 16

a This statement is a direct quote from Shimoda et al. 17

The other statements were composed for comparison and illustrative purposes only.

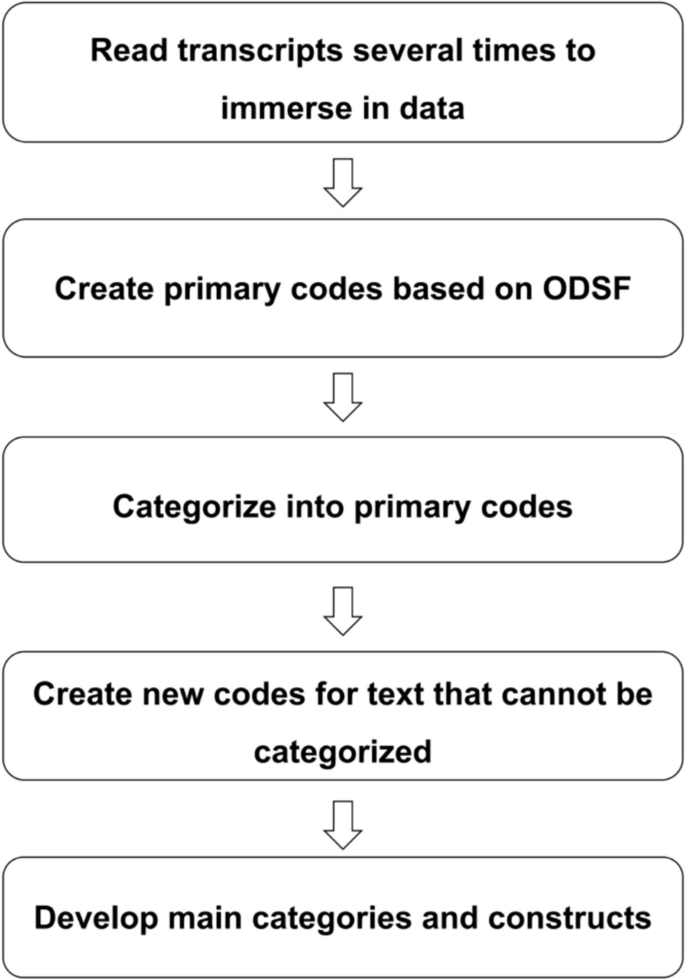

CONSTRUCTING RESEARCH QUESTIONS AND HYPOTHESES

To construct effective research questions and hypotheses, it is very important to 1) clarify the background and 2) identify the research problem at the outset of the research, within a specific timeframe. 9 Then, 3) review or conduct preliminary research to collect all available knowledge about the possible research questions by studying theories and previous studies. 18 Afterwards, 4) construct research questions to investigate the research problem. Identify variables to be accessed from the research questions 4 and make operational definitions of constructs from the research problem and questions. Thereafter, 5) construct specific deductive or inductive predictions in the form of hypotheses. 4 Finally, 6) state the study aims . This general flow for constructing effective research questions and hypotheses prior to conducting research is shown in Fig. 1 .

Research questions are used more frequently in qualitative research than objectives or hypotheses. 3 These questions seek to discover, understand, explore or describe experiences by asking “What” or “How.” The questions are open-ended to elicit a description rather than to relate variables or compare groups. The questions are continually reviewed, reformulated, and changed during the qualitative study. 3 Research questions are also used more frequently in survey projects than hypotheses in experiments in quantitative research to compare variables and their relationships.

Hypotheses are constructed based on the variables identified and as an if-then statement, following the template, ‘If a specific action is taken, then a certain outcome is expected.’ At this stage, some ideas regarding expectations from the research to be conducted must be drawn. 18 Then, the variables to be manipulated (independent) and influenced (dependent) are defined. 4 Thereafter, the hypothesis is stated and refined, and reproducible data tailored to the hypothesis are identified, collected, and analyzed. 4 The hypotheses must be testable and specific, 18 and should describe the variables and their relationships, the specific group being studied, and the predicted research outcome. 18 Hypotheses construction involves a testable proposition to be deduced from theory, and independent and dependent variables to be separated and measured separately. 3 Therefore, good hypotheses must be based on good research questions constructed at the start of a study or trial. 12

In summary, research questions are constructed after establishing the background of the study. Hypotheses are then developed based on the research questions. Thus, it is crucial to have excellent research questions to generate superior hypotheses. In turn, these would determine the research objectives and the design of the study, and ultimately, the outcome of the research. 12 Algorithms for building research questions and hypotheses are shown in Fig. 2 for quantitative research and in Fig. 3 for qualitative research.

EXAMPLES OF RESEARCH QUESTIONS FROM PUBLISHED ARTICLES

- EXAMPLE 1. Descriptive research question (quantitative research)

- - Presents research variables to be assessed (distinct phenotypes and subphenotypes)

- “BACKGROUND: Since COVID-19 was identified, its clinical and biological heterogeneity has been recognized. Identifying COVID-19 phenotypes might help guide basic, clinical, and translational research efforts.

- RESEARCH QUESTION: Does the clinical spectrum of patients with COVID-19 contain distinct phenotypes and subphenotypes? ” 19

- EXAMPLE 2. Relationship research question (quantitative research)

- - Shows interactions between dependent variable (static postural control) and independent variable (peripheral visual field loss)

- “Background: Integration of visual, vestibular, and proprioceptive sensations contributes to postural control. People with peripheral visual field loss have serious postural instability. However, the directional specificity of postural stability and sensory reweighting caused by gradual peripheral visual field loss remain unclear.

- Research question: What are the effects of peripheral visual field loss on static postural control ?” 20

- EXAMPLE 3. Comparative research question (quantitative research)

- - Clarifies the difference among groups with an outcome variable (patients enrolled in COMPERA with moderate PH or severe PH in COPD) and another group without the outcome variable (patients with idiopathic pulmonary arterial hypertension (IPAH))

- “BACKGROUND: Pulmonary hypertension (PH) in COPD is a poorly investigated clinical condition.

- RESEARCH QUESTION: Which factors determine the outcome of PH in COPD?

- STUDY DESIGN AND METHODS: We analyzed the characteristics and outcome of patients enrolled in the Comparative, Prospective Registry of Newly Initiated Therapies for Pulmonary Hypertension (COMPERA) with moderate or severe PH in COPD as defined during the 6th PH World Symposium who received medical therapy for PH and compared them with patients with idiopathic pulmonary arterial hypertension (IPAH) .” 21

- EXAMPLE 4. Exploratory research question (qualitative research)

- - Explores areas that have not been fully investigated (perspectives of families and children who receive care in clinic-based child obesity treatment) to have a deeper understanding of the research problem

- “Problem: Interventions for children with obesity lead to only modest improvements in BMI and long-term outcomes, and data are limited on the perspectives of families of children with obesity in clinic-based treatment. This scoping review seeks to answer the question: What is known about the perspectives of families and children who receive care in clinic-based child obesity treatment? This review aims to explore the scope of perspectives reported by families of children with obesity who have received individualized outpatient clinic-based obesity treatment.” 22

- EXAMPLE 5. Relationship research question (quantitative research)

- - Defines interactions between dependent variable (use of ankle strategies) and independent variable (changes in muscle tone)

- “Background: To maintain an upright standing posture against external disturbances, the human body mainly employs two types of postural control strategies: “ankle strategy” and “hip strategy.” While it has been reported that the magnitude of the disturbance alters the use of postural control strategies, it has not been elucidated how the level of muscle tone, one of the crucial parameters of bodily function, determines the use of each strategy. We have previously confirmed using forward dynamics simulations of human musculoskeletal models that an increased muscle tone promotes the use of ankle strategies. The objective of the present study was to experimentally evaluate a hypothesis: an increased muscle tone promotes the use of ankle strategies. Research question: Do changes in the muscle tone affect the use of ankle strategies ?” 23

EXAMPLES OF HYPOTHESES IN PUBLISHED ARTICLES

- EXAMPLE 1. Working hypothesis (quantitative research)

- - A hypothesis that is initially accepted for further research to produce a feasible theory

- “As fever may have benefit in shortening the duration of viral illness, it is plausible to hypothesize that the antipyretic efficacy of ibuprofen may be hindering the benefits of a fever response when taken during the early stages of COVID-19 illness .” 24

- “In conclusion, it is plausible to hypothesize that the antipyretic efficacy of ibuprofen may be hindering the benefits of a fever response . The difference in perceived safety of these agents in COVID-19 illness could be related to the more potent efficacy to reduce fever with ibuprofen compared to acetaminophen. Compelling data on the benefit of fever warrant further research and review to determine when to treat or withhold ibuprofen for early stage fever for COVID-19 and other related viral illnesses .” 24

- EXAMPLE 2. Exploratory hypothesis (qualitative research)

- - Explores particular areas deeper to clarify subjective experience and develop a formal hypothesis potentially testable in a future quantitative approach

- “We hypothesized that when thinking about a past experience of help-seeking, a self distancing prompt would cause increased help-seeking intentions and more favorable help-seeking outcome expectations .” 25

- “Conclusion

- Although a priori hypotheses were not supported, further research is warranted as results indicate the potential for using self-distancing approaches to increasing help-seeking among some people with depressive symptomatology.” 25

- EXAMPLE 3. Hypothesis-generating research to establish a framework for hypothesis testing (qualitative research)

- “We hypothesize that compassionate care is beneficial for patients (better outcomes), healthcare systems and payers (lower costs), and healthcare providers (lower burnout). ” 26

- Compassionomics is the branch of knowledge and scientific study of the effects of compassionate healthcare. Our main hypotheses are that compassionate healthcare is beneficial for (1) patients, by improving clinical outcomes, (2) healthcare systems and payers, by supporting financial sustainability, and (3) HCPs, by lowering burnout and promoting resilience and well-being. The purpose of this paper is to establish a scientific framework for testing the hypotheses above . If these hypotheses are confirmed through rigorous research, compassionomics will belong in the science of evidence-based medicine, with major implications for all healthcare domains.” 26

- EXAMPLE 4. Statistical hypothesis (quantitative research)

- - An assumption is made about the relationship among several population characteristics ( gender differences in sociodemographic and clinical characteristics of adults with ADHD ). Validity is tested by statistical experiment or analysis ( chi-square test, Students t-test, and logistic regression analysis)

- “Our research investigated gender differences in sociodemographic and clinical characteristics of adults with ADHD in a Japanese clinical sample. Due to unique Japanese cultural ideals and expectations of women's behavior that are in opposition to ADHD symptoms, we hypothesized that women with ADHD experience more difficulties and present more dysfunctions than men . We tested the following hypotheses: first, women with ADHD have more comorbidities than men with ADHD; second, women with ADHD experience more social hardships than men, such as having less full-time employment and being more likely to be divorced.” 27

- “Statistical Analysis

- ( text omitted ) Between-gender comparisons were made using the chi-squared test for categorical variables and Students t-test for continuous variables…( text omitted ). A logistic regression analysis was performed for employment status, marital status, and comorbidity to evaluate the independent effects of gender on these dependent variables.” 27

EXAMPLES OF HYPOTHESIS AS WRITTEN IN PUBLISHED ARTICLES IN RELATION TO OTHER PARTS

- EXAMPLE 1. Background, hypotheses, and aims are provided

- “Pregnant women need skilled care during pregnancy and childbirth, but that skilled care is often delayed in some countries …( text omitted ). The focused antenatal care (FANC) model of WHO recommends that nurses provide information or counseling to all pregnant women …( text omitted ). Job aids are visual support materials that provide the right kind of information using graphics and words in a simple and yet effective manner. When nurses are not highly trained or have many work details to attend to, these job aids can serve as a content reminder for the nurses and can be used for educating their patients (Jennings, Yebadokpo, Affo, & Agbogbe, 2010) ( text omitted ). Importantly, additional evidence is needed to confirm how job aids can further improve the quality of ANC counseling by health workers in maternal care …( text omitted )” 28

- “ This has led us to hypothesize that the quality of ANC counseling would be better if supported by job aids. Consequently, a better quality of ANC counseling is expected to produce higher levels of awareness concerning the danger signs of pregnancy and a more favorable impression of the caring behavior of nurses .” 28

- “This study aimed to examine the differences in the responses of pregnant women to a job aid-supported intervention during ANC visit in terms of 1) their understanding of the danger signs of pregnancy and 2) their impression of the caring behaviors of nurses to pregnant women in rural Tanzania.” 28

- EXAMPLE 2. Background, hypotheses, and aims are provided

- “We conducted a two-arm randomized controlled trial (RCT) to evaluate and compare changes in salivary cortisol and oxytocin levels of first-time pregnant women between experimental and control groups. The women in the experimental group touched and held an infant for 30 min (experimental intervention protocol), whereas those in the control group watched a DVD movie of an infant (control intervention protocol). The primary outcome was salivary cortisol level and the secondary outcome was salivary oxytocin level.” 29

- “ We hypothesize that at 30 min after touching and holding an infant, the salivary cortisol level will significantly decrease and the salivary oxytocin level will increase in the experimental group compared with the control group .” 29

- EXAMPLE 3. Background, aim, and hypothesis are provided

- “In countries where the maternal mortality ratio remains high, antenatal education to increase Birth Preparedness and Complication Readiness (BPCR) is considered one of the top priorities [1]. BPCR includes birth plans during the antenatal period, such as the birthplace, birth attendant, transportation, health facility for complications, expenses, and birth materials, as well as family coordination to achieve such birth plans. In Tanzania, although increasing, only about half of all pregnant women attend an antenatal clinic more than four times [4]. Moreover, the information provided during antenatal care (ANC) is insufficient. In the resource-poor settings, antenatal group education is a potential approach because of the limited time for individual counseling at antenatal clinics.” 30

- “This study aimed to evaluate an antenatal group education program among pregnant women and their families with respect to birth-preparedness and maternal and infant outcomes in rural villages of Tanzania.” 30

- “ The study hypothesis was if Tanzanian pregnant women and their families received a family-oriented antenatal group education, they would (1) have a higher level of BPCR, (2) attend antenatal clinic four or more times, (3) give birth in a health facility, (4) have less complications of women at birth, and (5) have less complications and deaths of infants than those who did not receive the education .” 30

Research questions and hypotheses are crucial components to any type of research, whether quantitative or qualitative. These questions should be developed at the very beginning of the study. Excellent research questions lead to superior hypotheses, which, like a compass, set the direction of research, and can often determine the successful conduct of the study. Many research studies have floundered because the development of research questions and subsequent hypotheses was not given the thought and meticulous attention needed. The development of research questions and hypotheses is an iterative process based on extensive knowledge of the literature and insightful grasp of the knowledge gap. Focused, concise, and specific research questions provide a strong foundation for constructing hypotheses which serve as formal predictions about the research outcomes. Research questions and hypotheses are crucial elements of research that should not be overlooked. They should be carefully thought of and constructed when planning research. This avoids unethical studies and poor outcomes by defining well-founded objectives that determine the design, course, and outcome of the study.