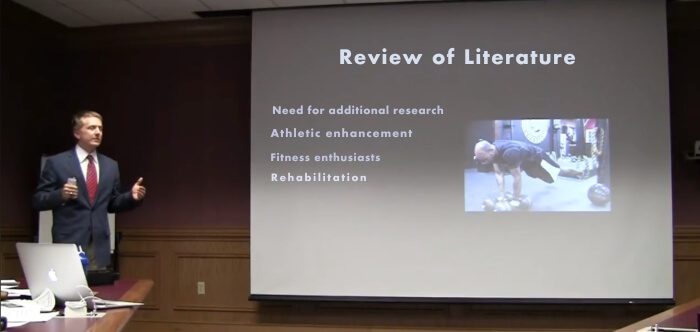

How Do You Present a Literature Review in a Conference?

Presenting a literature review at a conference is an art that balances information delivery with engaging storytelling. In the context of “How do you present a literature review in a conference?” it’s essential to transform your extensive review into a concise, impactful presentation.

The presentation involves highlighting key findings, elaborating on methodologies, and illustrating their significance in relation to the conference’s theme. To captivate your audience, incorporate visuals and accurately cite your sources, ensuring your presentation is both informative and visually appealing.

Moreover, an engaging delivery style can substantially impact audience reception. Be prepared to handle questions and encourage discussions, turning your presentation into an interactive learning experience. For more insights and detailed guidance, continue reading our comprehensive article.

What Is the Literature Review?

A literature review is a scholarly endeavor that synthesizes existing research on a specific topic. It’s not merely a summary; it critically analyzes and links various studies. This comprehensive overview helps identify patterns, gaps, and the current state of knowledge.

In undertaking a literature review, the researcher examines relevant publications to establish an understanding of the subject. This process involves evaluating sources’ relevance, credibility, and contributions to the field. The outcome is a cohesive narrative contextualizing the research within its academic landscape, providing a foundation for new inquiries.

Can You Present a Literature Review at A Conference?

Yes, presenting a literature review at a conference is a valuable contribution. It offers insights into existing research and highlights emerging trends in a specific field. This presentation can spark discussions and foster academic collaborations.

When presenting a literature review at an event with multinational participants , the key is to distill complex information into accessible insights. This involves selecting key studies, weaving them into a narrative, and emphasizing their collective significance. Such a presentation can illuminate research gaps, setting the stage for future work.

In doing so, the presenter navigates through various studies, offering a critical analysis and synthesis. This approach educates and engages the audience, inviting them to explore the subject deeper. The literature review thus catalyzes knowledge exchange and scholarly debate at the conference.

Why Should You Present Your Literature Review at A Conference?

Presenting a literature review at a conference is a strategic move for any researcher or academic. It is a platform to share findings, gain feedback, and engage with peers. This opportunity can significantly impact one’s academic journey and research direction.

- Showcasing Expertise : Presenting a review establishes you as a knowledgeable professional. It highlights your ability to analyze and synthesize complex information.

- Networking Opportunities : Conferences attract like-minded professionals, offering a space to build valuable connections. Sharing your review can lead to collaborations and future research opportunities.

- Receiving Constructive Feedback : Peer conference feedback can refine your understanding and approach. This interaction often leads to improvements in your research methodology and perspective.

- Identifying Research Gaps : Discussing your review exposes you to different viewpoints, revealing gaps in current research. This insight can guide your future research endeavors.

Presenting a literature review at a conference is not just about sharing knowledge; it’s a gateway to professional growth, collaboration, and refining your research. It’s an invaluable experience for anyone looking to make a mark in their academic field.

How Do You Present a Literature Review in A Conference?

The process of presenting a literature review at a conference requires careful preparation and strategic execution. It involves a deep understanding of the subject matter and the ability to succinctly and engagingly convey complex ideas. This guide offers a structured approach to ensure your presentation is impactful and memorable.

Step 1: Understand Your Audience

Before you begin, assess who will be attending your session. Tailor your presentation to their knowledge level, interests, and the conference theme.

Step 2: Condense Your Content

Select key findings and essential studies from your review. Focus on presenting these elements clearly and concisely to maintain audience engagement.

Step 3: Create a Compelling Narrative

Weave your selected studies into a story that highlights their relevance and interconnections. This narrative approach makes your presentation more relatable and easier to follow.

Step 4: Utilize Visual Aids

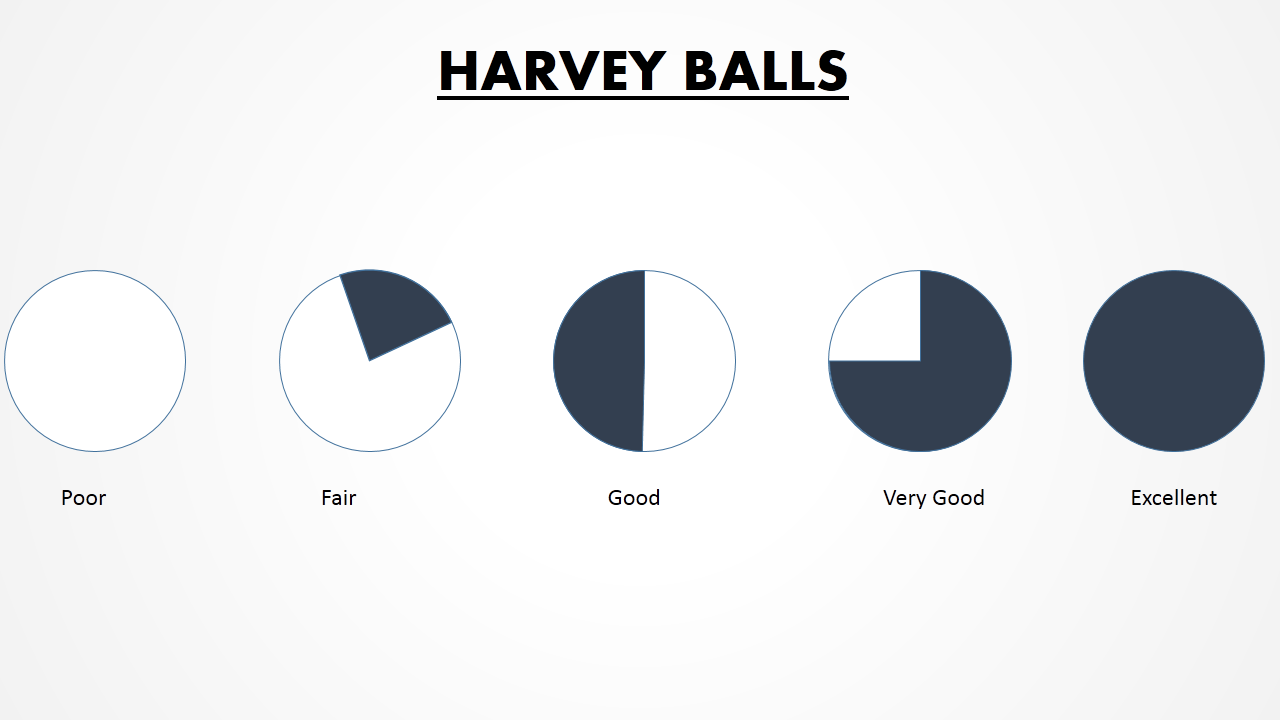

Incorporate visuals like graphs, charts, and infographics to illustrate complex points. These aids can make your presentation more dynamic and understandable.

Step 5: Practice Your Delivery

Rehearse your presentation multiple times. Focus on clarity, pacing, and maintaining a conversational tone to keep your audience engaged.

Step 6: Prepare for Questions

Anticipate potential questions and prepare thoughtful responses. Engaging with your audience in this way can deepen their understanding and interest.

A literature review at a conference offers an ideal platform for showcasing your work and engaging with the academic community. Your presentation will be both informative and engaging if you follow these steps.

Considerations While Presenting Your Paper at A Conference

Presenting a paper at a conference is a crucial moment for any researcher or academic. It’s an opportunity to share your work with peers and experts in your field, receive feedback, and build your professional network. However, several considerations should be taken into account to ensure the presentation is effective and well-received.

- Understand Your Audience : Tailor your presentation to the audience’s expertise and interests. This ensures that your content is relevant and engaging to them.

- Clarity and Conciseness : Be clear and to the point in your delivery. Avoid overloading your presentation with excessive detail or jargon.

- Effective Use of Visuals : Use visuals like charts and slides to complement your speech. Ensure they are clear, relevant, and aid in understanding your points.

- Engaging Delivery : Practice your speech to maintain a natural, confident tone. Avoid monotonous delivery to keep the audience interested.

- Time Management : Adhere strictly to your allotted time slot. Plan your presentation to cover all points without rushing or overextending.

- Prepare for Questions : Anticipate questions and prepare concise, informative answers. This interaction can enhance the audience’s understanding of your work.

A successful conference presentation starts by understanding your audience’s needs and interests. Clear and engaging communication ensures your message resonates, while effective visuals enhance comprehension and retention.

Good time management keeps the presentation focused and allows for interactive discussions or Q&A sessions, fostering deeper engagement with your audience. By considering these factors, you can ensure that your presentation not only conveys your research effectively but also leaves a positive impression on your audience.

Tips to Select the Right Conference for Presenting Your Literature Review

Selecting the right conference to present your research is a critical decision that can significantly impact your academic and professional journey. It’s about finding a platform where your work will be appreciated and can contribute meaningfully to the field. This guide provides strategic tips to help you make an informed choice.

Relevance to Your Field

Choose a conference that aligns closely with your research area. This ensures your work is relevant to the attendees. Look for events where current trends and developments in your field are discussed. A conference with a specific focus can provide a more engaged audience for your topic.

Conference Reputation

Research the conference’s standing in the academic community. Established conferences often attract high-quality research and renowned speakers. Check past conference proceedings to gauge the quality of presentations. A reputable conference can add significant value to your CV and professional profile.

Type of Audience

Consider the typical audience of the conference. Whether it’s more academic or industry-focused can affect the reception of your work. A diverse audience can provide varied perspectives, enriching the discussion around your research. Tailor your presentation to suit the audience for maximum impact.

Networking Opportunities

Evaluate the networking potential of the conference. Conferences are excellent for meeting peers, mentors, and leaders in your field. Look for events that facilitate networking, such as workshops or social gatherings. Networking can open doors to collaborations and future research opportunities.

Publication Opportunities

Some conferences offer publication opportunities in journals or conference proceedings. Choose conferences where your work has the potential to be published. This can provide broader exposure and enhance your research’s credibility. Ensure the publication aligns with reputable and relevant academic journals.

Location and Accessibility

Consider the conference’s location and your ability to attend. The benefits of attending top-notch international conferences are appealing; however, local or regional conferences can also be beneficial. Factor in travel costs, visa requirements, and the conference’s accessibility. Sometimes, a nearby conference can offer more engagement and less logistical stress.

Selecting the right conference requires careful consideration of factors like relevance, reputation, audience type, networking opportunities, publication potential, and location. Making an informed choice can enhance your presentation’s impact, contribute to your professional development, and broaden your academic horizons.

Closing Remarks

In summarizing the key aspects of presenting a literature review at a conference, it’s clear that meticulous preparation and strategic considerations are paramount. From understanding your audience to selecting the right conference, each step is crucial for a successful presentation. “How do you present a literature review in a conference?” becomes a question of not just content, but context and delivery.

Accurate application of these principles ensures that your literature review is not only well-received but also stands out as a significant contribution to your field. Missteps in any of these areas, whether in presentation style or conference selection, can lead to missed opportunities and diminished impact.

Thus, the importance of precision and thoroughness in every aspect of conference presentation cannot be overstated. This holistic approach shapes not only how your work is perceived but also your professional trajectory in the academic community.

Leave a Comment Cancel Reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Don’t miss our future updates! Get subscribed today!

Sign up for email updates and stay in the know about all things Conferences including price changes, early bird discounts, and the latest speakers added to the roster.

Meet and Network With International Delegates from Multidisciplinary Backgrounds.

Useful Links

Quick links, secure payment.

Copyright © Global Conference Alliance Inc 2018 – 2024. All Rights Reserved. Developed by Giant Marketers Inc .

DEAN’S BOOK w/ Prof. CONNIE GRIFFIN

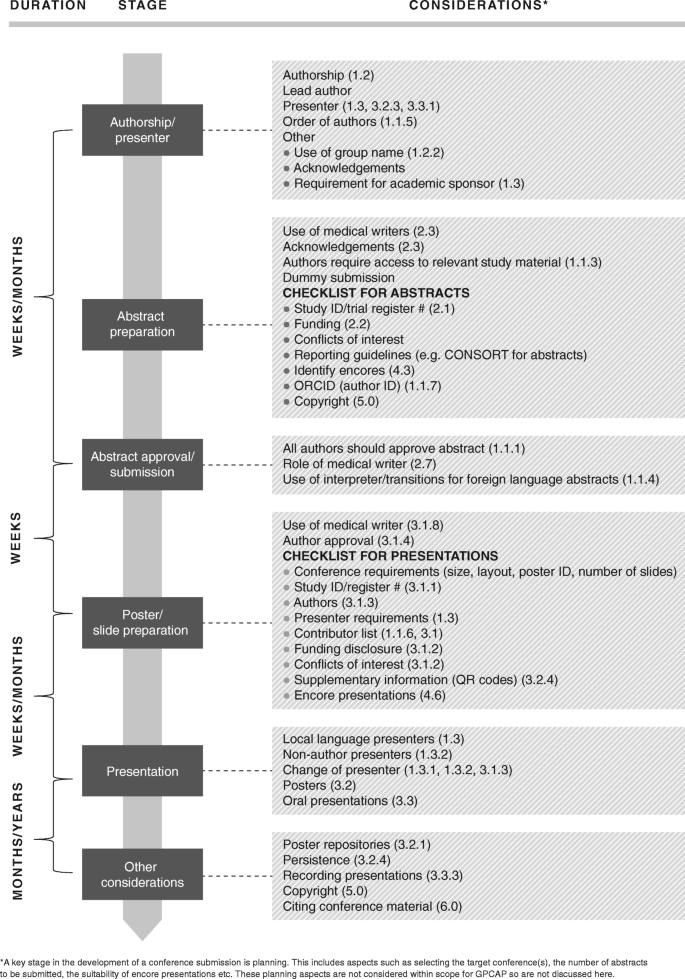

Honors291g-cdg’s blog, literature review/poster presentation guide.

Literature Review & Poster/Visual Presentation Guide GIVING & GETTING EFFECTIVE PRESENTATIONS PRESENTATIONS In many disciplines presentations are given at academic conferences, symposia, and other places where scholars share their work with one another (including the Massachusetts Undergraduate Research Conference). It can be very challenging to display and communicate all of one’s research findings in a synthesized manner and short timeframe. Following are some thoughts about both preparing your presentation and also how to maximize your experience as an audience member. I. PRESENTER’S ROLE: The overall purpose of your presentation is to share your research process and findings with the class. In all cases, whatever topic you choose for your research, the objective is to stimulate in your listeners an understanding of that topic and how you went about developing that understanding for yourself as a researcher. The purpose of your talk is to present your research. Keep that goal in mind as you consider what to include and how to organize it.. In the visual portion of your presentation, be sure to include the following:

1) Title 2) Your research question 3) Examples of what you found (results) including a. Visual and quantitative information b. Important quotes 4) Your conclusion

Remember to keep your presentation (and your visual material) concise. It is very easy to overwhelm an audience with too much text. Also, be sure to use a font size that is large enough to read from several feet away. Presentation considerations. Five minutes go fast! Therefore, stick with the most important points (details can come in the Q&A session), and be sure to organize your presentation logically. Be sure to practice. Nothing will prepare you better than giving your presentation several times to an audience. Speak slowly, clearly, expressively. Make eye contact. Also make sure your visual really does support your oral presentation and aid your audience! Concluding your presentation. End your presentation with a quick summary or suggestion of what’s been gained by your research. Then be prepared for questions. Be ready with a question of your own in case the audience needs prompting. A crucial part of your presentation is thinking about how to engage the audience. Listen closely, be sure you understand each questioner’s intent, and then answer as directly as possible. II. AUDIENCE’S ROLE: Even when not presenting, you play a crucial role in the presentation and determining its quality. As a listener, demonstrate your interest: make eye contact with the presenter as you listen closely, and take notes so you can ask informed, pertinent, and helpful questions during the Q&A period. Putting a presenter at ease can go a long way to ensuring an effective presentation.

The Cersonsky Lab at UW-Madison

The Cersonsky Lab is a research group based at the University of Wisconsin - Madison, Department of Chemical and Biological Engineering

8 Tips for a Literature Review Presentation

by Caleb Youngwerth

Literature reviews for research are very different from any other presentation you may have done before, so prepare to relearn how to present. The goals of research literature reviews are different, the style is different, even the pacing is different. Even if you have previously done a literature review in an academic setting, you will still want to know these tips. I found this out the hard way, so you don’t have to. Also, to clarify, these tips are meant for a literature review of a topic, not a singular study or paper, though many of the tips do apply to both.

1. Highlight current research

The point of a literature review for research is to highlight the current state of research related to your topic, not to simply give background information. Background information is important and should be included, but the focus of the presentation should be showing some current studies that either confirm or challenge the topic you are studying. As much as textbooks from 30 years ago might seem to have all the information you need for your presentation, a research study from this decade does a far better job representing the current state of the topic, which is the end goal of the presentation. Also, since the new research should be the focal point of the presentation, as a general piece of advice, try to give each research study a minimum of one full slide, so you can give a fuller picture of what the study actually concluded and how they reached their conclusion.

2. Alternate old and new

The best way to keep people listening to your presentation is to vary what you include in your presentation. Rather than trying to give all of the background information first and then showcase all the flashy new research, try to use the two interchangeably. Organize the presentation by idea and give all the background needed for the idea, then develop the idea further by using the new research studies to help illustrate your point. By doing this, you not only avoid having to backtrack and reteach the background for each and every new study, but also help keep the presentation interesting for the audience. This method also helps the audience avoid being overwhelmed since only a little bit of new information is introduced at a time. Obviously, you may need to include a brief introductory section that contains nothing but textbook information that is absolutely necessary to understand anything about the topic, but the more varied the presentation, the better.

3. Use complete sentences

Every presentation class up to this point probably has taught you that slides with full sentences are harmful to your presentation because it is distracting to the listener. Unlearn all that information for this style of presentation. Bullet points are still good, but you should have complete ideas (which usually means complete sentences) for every single point. If someone would be able to read your slides and not hear you, and still be able to understand most of your presentation, your literature review is perfect in a research setting. The point of this presentation is to share all the new information you have learned, so hiding it is helping no one. You still do not want to be reading your slides verbatim and can absolutely add information beyond the slides, but all your main ideas should be on the slides.

4. Read smart

I will admit that I stole this tip from Rosy, but it is a very good tip, so I decided to include it. When you read, you want to read as much as you can, but wasting time reading an irrelevant research study is helping no one. When finding a new study, read the abstract, then the conclusion, then the pictures. If it looks like a good study from those three parts, or you personally find it interesting, you then can go over the actual paper and read it, but by reading the less dense parts first, you can get a general idea of the study without actually having to take a lot of time to read the entire paper. Though textbooks and review papers generally are a little more difficult to read using this method, you can still look at the introduction, pictures, and conclusion and save time reading the rest if the source ends up not being interesting or important.

5. Reading is good for you

As much as you want to read smart when you can, the more you read, the more knowledgeable you become. The goal of the presentation is to become an expert on you topic, so the only way you can do that is by reading as much as you can. You should read more information than you present, since many sources you read probably will not fit in a time-constrained presentation. As Rosy likes to say, in anything research, only about 10% of what you know should actually be shared with the world. By reading more, you are better-suited to answer questions, and you also just generally are able to understand what you are studying better because, chances are, the main purpose of this presentation for you is to help you better understand your research. If something looks interesting and is vaguely related to your topic, read it; it will be beneficial to you, even if you do not end up presenting the information.

6. Let pictures talk for you

When reading research papers, the pictures are usually the best part. Your presentation should be the same way. The best way to be able to show the concept you are trying to explain is to literally show it. The best way to show the results of a research study is usually by showing a graph or infographic, so if the paper has a graph that shows the results, you should absolutely use it. Charts, diagrams, and even videos can also help illustrate a piece of background information that might be difficult to put into words. That being said, you should know and be able to explain every single part of the graphic. Otherwise, it loses meaning and makes the audience even more confused. Captions can and should be used to help explain the graphic, not only to remind you, but also let your audience know what the general idea of the graphic is. Since they keep slides interesting, you should probably have some sort of picture on every slide, otherwise the slides will be not only bland, but also likely less informative.

7. Avoid overcrowded slides

Just because you should have a lot of information in your presentation does not mean that your slides need to show that. In fact, a slide with too much information will only harm your presentation since your audience will be distracted trying to read all of a long slide while you are trying to explain it. Doing anything to make slides less dense will help avoid having the audience focused on the slide, so they focus on you more. Transitions that only show one point at a time or wait to reveal an image can be helpful in breaking up an overcrowded slide. Also, simply adding more slides can help since it accomplishes the purpose of putting less information on your slides while still keeping the exact same amount of information. You still want to share as much information as you can with the audience, but overcrowded slides do not accomplish this purpose.

8. Expect questions

Another thing that might be slightly different about a research presentation is questions. Most presentations have the question section after the presenter has finished. Research presentations are different because they allow for questions during the presentation (assuming it is a presentation to a small group). If you get any questions in the middle of the presentation, it is not someone being rude, but simply a fellow researcher who is legitimately curious about your topic. Of course, there will be a question period after the presentation, but you may be asked questions during the presentation. If you read enough information on the topic, you should be able to answer any question easily, but if the question is completely unrelated to anything you read, then it is perfectly reasonable to answer that you did not research the specific area in question. Overall, the questions related to your presentation should not be your biggest worry, but you should definitely be ready.

These are not all the rules for a literature review presentation nor are they set in stone. These are just some tips that I was told or learned that were the most helpful for me, so I hope they will help you too. I had to rewrite my presentation entirely my first literature review because I did not understand some of these differences, so if you give the presentation when you are scheduled to go, you are already better off than I was. Also, do not be afraid to ask anyone in the research group, even Rosy, if you need help. Chances are everyone in the group has given a literature review presentation at some point, so we would be more than happy to help you if you are confused about something. That being said, we are not experts on your topic, so specific questions about organization and content are going to have to be figured out by yourself. Either way, no matter what you do, do not stress out about this presentation. The goal of the presentation is mostly just to help improve your knowledge on a topic, and the presentation is simply to share with the group some of the information you have learned. Best of luck with the presentation, and I hope these tips help clear up what exactly the goal of a literature review presentation in a research setting is.

Jump to navigation

Cochrane Training

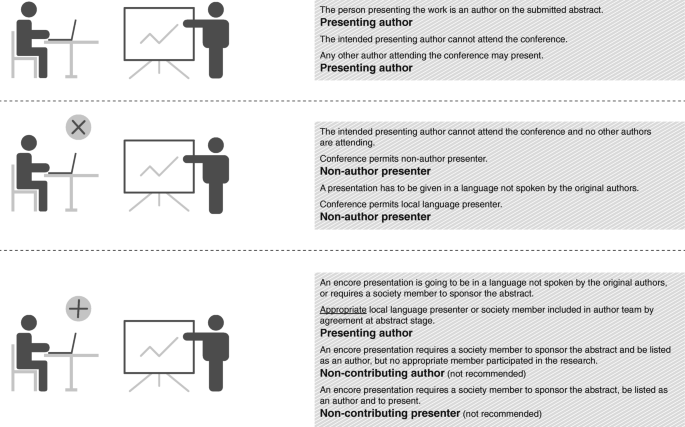

Presenting at conferences.

Academic conferences are a useful way to present the results of a Cochrane review to people either through an oral presentation, a poster presentation, or a booth. Conferences also have the additional benefit of networking and an opportunity to promote both Cochrane and the results of your review to peers.

How to present at conferences

Oral presentation.

Good oral presentations should be captivating, get the message across clearly, consider the language and context of the audience, and keep people engaged throughout. Not everyone can be an expert public speaker, and in many ways, it takes practice to become good at delivering engaging oral presentations. Our resources below can help.

The ‘Community Templates’ section on the brand resources page provides templates for PowerPoint presentations that can be used at conferences. There is a video on Creating a PowerPoint Presentation to explain how to use the template.

This video gives some tips for effective presentations at conferences such as:

- Choosing your content

- Using an appropriate structure

- Eliminating jargon

- Creating effective slides

- Finding your passion!

Poster presentation

Make your poster one that people want to stop and look at when you are at a conference. If you are preparing a poster presentation, these resources will help your work stand out in a sea of posters:

- The ‘Community Templates’ on the brand resources page provide pre-branded poster templates. They are very simple to use – you just need to download and add in the content.

- Cochrane officially endorses the #betterposter design. These new templates offer posters with less text and a decluttered design with the main finding in plain English as the highlighted feature. Learn more about the design and watch a quick introduction.

- This information sheet contains useful questions for preparing a poster for a conference.

Conference booth

At some conferences, you may have the opportunity to showcase your work at a booth. If you have multiple dissemination products that you created, you can display them here. You might also want to bring screens or computers to make your booth more interactive. Like posters, you want to make sure your booth is one that people want to visit and interact with.

You can contact Cochrane to discuss your event , get clarification on Cochrane event policies, or help with event branding such as special banners, flyers or branded items to give away.

If you are hosting the symposium or conference, contact Cochrane to have it listed and promoted on our website.

Sharing your presentation

When you know you'll be presenting at a conference, share the details on social media. For more information on social media platforms and how to use them effectively, visit this page. On social media, tell people where you are going, what you'll be presenting, and provide a link to sign up to attend (if possible).

During your presentation, you might want to consider having a colleague or peer live-tweeting. This will give you content to re-tweet later, and give people in the room content to share as well. Others in the room might also be tweeting about your presentation, which you can re-tweet later. You might want to consider live streaming your presentation on YouTube, Facebook or Instagram so your followers who aren’t in attendance can watch you present in real time.

If you don’t have your own social media accounts, we can share a picture of you at a conference on Cochrane’s social media. It is great to get a picture beside your poster, at your booth, or beside something with the conference name. If you are interested, please send the following to Muriah Umoquit at [email protected] : - Your name - Your Instagram/Twitter handle if you want it included - The related Review or Centre group - Title of your poster or presentation - Link to Cochrane Review if appropriate - Title of the conference - Official conference hashtag - A picture

After your presentation, you can distribute materials to your audience so that the information stays with them. This could be copies or recordings of the presentation, or another dissemination product related to what you presented. You can distribute in person at the conference, afterwards if you have the details of who attended your session, or through social media for anyone who may have followed you on a social media platform because of your presentation.

Evaluating the effect of your presentation

Many conferences will do their own evaluation of their conference programming, including oral presentations that were given. They may ask attendees questions about the topic that was presented, the effectiveness of the presenters, and the quality of the presentation. Ask your conference host whether they evaluate presentations. If they do, you can request feedback on your presentation that way.

You can also seek feedback on your own from your audience if you gave a presentation. You can do this through hard copy surveys at tables or chairs that you can collect, through email after your presentation, or you can do live evaluation surveys. These work by surveying people in real time through posing a question you can embed in your presentation, and have audience members provide input on their phones by visiting a link you give them. Sli.do and Menti are popular tools for this.

Examples of presenting at conferences by Cochrane groups

This is a great case study of how Cochrane UK used a booth at a conference – with great tips on what to do before, during, and after the conference.

Back to top

Journal of Education and Research in Nursing

Guidelines for Conducting a Literature Review and Presenting Conference Papers

A literature review provides a solid background for a research paper and reveals a comprehensive knowledge of the literature. Apart from providing you with a useful overview of a particular subject area, a literature review is important for keeping you up to date with what is current in your field. There is no simple recipe for good conference presentations and scholars in different disciplines will take different approaches. Finally, the quality, of the literature review provides an academic with credibility in his or her field. This literature review and conference papers should be prepared very seriously. This paper will outline the nature and purpose of a literature review and present guidelines for how to conduct and write a literature review and also will give practical knowledge about preparing and presenting of good conference.

Derleme Makale Yazımında, Konferans ve Bildiri Sunumu Hazırlamada Pratik Bilgiler

Derleme makaleler belirli bir konunun yararlı bir ‘toparlaması’ olmanın yanı sıra, araştırmacıların uzmanlık alanlarındaki yenilikleri izleyebilmeleri açısından da son derece önemlidir. Bu tip çalışmalar araştırma makalelerine dayanak oluşturdukları gibi kapsamlı bir literatür taramasını da içerir. Başarılı bir konferans ya da bildiri sunumunun basit bir reçetesi yoktur ve farklı disiplinlerde çalışan akademisyenlerin de farklı yaklaşımları söz konusu olmaktadır. Bir akademisyenin kendi alanındaki prestijine katkıda bulunan bu yazıların ve konferans ya da bildiri sunumlarının özenle hazırlanmaları gerekir. Bu yazıda, derleme makalenin temel yapısı ile amaçlarının özetlenmesi, başarılı bir derleme yazı, konferans veya bildiri sunumu hazırlama ve bu bildirilerin sunumuna yönelik pratik bilgilerin iletilmesi amaçlandı.

Journal Citation Indicator: 0.18 CiteScore: 1.1 Source Normalized Impact per Paper: 0.22 SCImago Journal Rank: 0.348

- Abstrating and Indexing

- Aim and Scope

- Editorial Board

- Ethics Policy

- ICMJE Recommendations

- Koç University Semahat Arsel Nursing Education and Research Center

Copyright © 2024 Journal of Education and Research in Nursing

- - Google Chrome

Intended for healthcare professionals

- Access provided by Google Indexer

- My email alerts

- BMA member login

- Username * Password * Forgot your log in details? Need to activate BMA Member Log In Log in via OpenAthens Log in via your institution

Search form

- Advanced search

- Search responses

- Search blogs

- How to prepare an...

How to prepare an effective research poster

- Related content

- Peer review

- Lucia Hartigan , registrar 1 ,

- Fionnuala Mone , fellow in maternal fetal medicine 1 ,

- Mary Higgins , consultant obstetrician 1 2

- 1 National Maternity Hospital, Dublin

- 2 Obstetrics and Gynaecology, Medicine and Medical Sciences, University College Dublin

- mhiggins{at}nmh.ie

Being asked to give a poster presentation can be exciting, and you need not be daunted by the prospect of working out how to prepare one. As Lucia Hartigan and colleagues explain, many options are available

The long nights are over, the statistics have been run, the abstract has been written, and the email pops into your inbox: “Congratulations! You have been accepted for a poster presentation.”

All that work has been worthwhile. Your consultant congratulates you and your colleagues are envious of your having a legitimate excuse to go away for a couple of days, but now you have to work out how to prepare a poster. Do not despair, for you have many options.

Firstly, take this seriously. A poster is not a consolation prize for not being given an oral presentation. This is your chance to show your work, talk to others in the field, and, if you are lucky, to pick up pointers from experts. Given that just 45% of published abstracts end in a full paper, 1 this may be your only chance to get your work out there, so put some effort into it. If you don’t have access to the services of a graphic designer, then some work will be entailed as it normally takes us a full day to prepare the layout of a poster. If you are lucky enough to have help from a graphic designer, then you will need to check that the data are correct before it is sent to the printer. After all, it will be your name on the poster, not the graphic designer’s.

Secondly, check the details of the requirements. What size poster should you have? If it is too big, it may look arrogant. If it is too small, then it may seem too modest and self effacing. Should it be portrait or landscape? Different meetings have different requirements. Some may stay with traditional paper posters, so you need to factor in printing. Others present them electronically, but may have a deadline by which you need to have uploaded the poster. When planning a meeting the organisers work out how many poster boards there will be and then the numbers, so follow their requirements and read the small print.

Then make a template. It can be tempting to “borrow” a poster template from someone else, and this may buy you some time, but it is important to check what page set-up and size have been selected for the template. If it’s meant for an A2 size and you wish to print your poster on A0 paper, then the stretching may lead to pixillation, which would not look good.

Next, think about your layout. Use text boxes to cover the following areas: title (with authors, institution, and logo), background, methods, results, and conclusions. Check that the text boxes are aligned by using gridlines, and justify your text. Use different colours for titles, and make sure you can read the title from 3 metres away. Some people will put their abstract in a separate box in the top right hand corner underneath the title, and then expand a little in the other areas. That is fine, so long as you follow the golden rule of writing a poster: do not include too much text. One study showed that less than 5% of conference attendees visit posters at meetings and that few ask useful questions. 2 The same research found that, in addition to the scientific content of a poster, the factors that increase visual appeal include pictures, graphs, and a limited use of words. 2 The ideal number of words seems to be between 300 and 400 per square metre.

Now make it look pretty and eye catching, and use lots of graphics. Outline text boxes or fill them with a different colour. If you can present the data using a graph, image, or figures rather than text, then do so, as this will add visual appeal. If you want to put a picture in the background, and it is appropriate to do so, fade the image so that it does not distract from the content.

Fonts are important. Check whether the meeting has set criteria for fonts; if they have, then follow them. You do not want to stand out for the wrong reason. If there are no specified criteria, then the title should be in point size 72-84, depending on the size of the poster. The authors’ names should be either the same size, but in italics, or else a couple of sizes smaller.

If you are including the hospital logo, don’t take a picture that will not size up properly when enlarged. Instead, obtain a proper copy from the hospital administrators.

References can be in small writing. No one is likely to read them, and you are including them only to remind yourself what you learnt in the literature review. One intriguing possibility is the use of a trigger image to link the poster to online content. 3

Finally, there are also things you should not do. Don’t leave your figures unlabelled, include spelling errors, use abbreviations without an explanation, or go outside the boundaries of the poster. Don’t be ashamed that you “only” have a poster. At a good meeting you may find that the comments from passers by are an amazing peer review. We have presented at meetings where world experts have given feedback, and with that feedback we have written the paper on the flight home.

Competing interests: We have read and understood the BMJ Group policy on declaration of interests and have no relevant interests to declare.

- ↵ Scherer RW, Langenberg P, von Elm E. Full publication of results initially presented in abstracts. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2007 ; 2 : MR000005 . OpenUrl PubMed

- ↵ Goodhand JR, Giles CL, Wahed M, Irving PM, Langmead L, Rampton DS. Poster presentations at medical conferences: an effective way of disseminating research? Clin Med 2011 ; 1 : 138 -41. OpenUrl

- ↵ Atherton S, Javed M, Webster S, Hemington-Gorse S. Use of a mobile device app: a potential new tool for poster presentations and surgical education. J Visual Comm Med 2013 ; 36 (1-2): 6 -10. OpenUrl

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Health Serv Res

- v.42(1 Pt 1); 2007 Feb

Preparing and Presenting Effective Research Posters

Associated data.

APPENDIX A.2. Comparison of Research Papers, Presentations, and Posters—Contents.

Posters are a common way to present results of a statistical analysis, program evaluation, or other project at professional conferences. Often, researchers fail to recognize the unique nature of the format, which is a hybrid of a published paper and an oral presentation. This methods note demonstrates how to design research posters to convey study objectives, methods, findings, and implications effectively to varied professional audiences.

A review of existing literature on research communication and poster design is used to identify and demonstrate important considerations for poster content and layout. Guidelines on how to write about statistical methods, results, and statistical significance are illustrated with samples of ineffective writing annotated to point out weaknesses, accompanied by concrete examples and explanations of improved presentation. A comparison of the content and format of papers, speeches, and posters is also provided.

Each component of a research poster about a quantitative analysis should be adapted to the audience and format, with complex statistical results translated into simplified charts, tables, and bulleted text to convey findings as part of a clear, focused story line.

Conclusions

Effective research posters should be designed around two or three key findings with accompanying handouts and narrative description to supply additional technical detail and encourage dialog with poster viewers.

An assortment of posters is a common way to present research results to viewers at a professional conference. Too often, however, researchers treat posters as poor cousins to oral presentations or published papers, failing to recognize the opportunity to convey their findings while interacting with individual viewers. By neglecting to adapt detailed paragraphs and statistical tables into text bullets and charts, they make it harder for their audience to quickly grasp the key points of the poster. By simply posting pages from the paper, they risk having people merely skim their work while standing in the conference hall. By failing to devise narrative descriptions of their poster, they overlook the chance to learn from conversations with their audience.

Even researchers who adapt their paper into a well-designed poster often forget to address the range of substantive and statistical training of their viewers. This step is essential for those presenting to nonresearchers but also pertains when addressing interdisciplinary research audiences. Studies of policymakers ( DiFranza and the Staff of the Advocacy Institute 1996 ; Sorian and Baugh 2002 ) have demonstrated the importance of making it readily apparent how research findings apply to real-world issues rather than imposing on readers to translate statistical findings themselves.

This methods note is intended to help researchers avoid such pitfalls as they create posters for professional conferences. The first section describes objectives of research posters. The second shows how to describe statistical results to viewers with varied levels of statistical training, and the third provides guidelines on the contents and organization of the poster. Later sections address how to prepare a narrative and handouts to accompany a research poster. Because researchers often present the same results as published research papers, spoken conference presentations, and posters, Appendix A compares similarities and differences in the content, format, and audience interaction of these three modes of presenting research results. Although the focus of this note is on presentation of quantitative research results, many of the guidelines about how to prepare and present posters apply equally well to qualitative studies.

WHAT IS A RESEARCH POSTER?

Preparing a poster involves not only creating pages to be mounted in a conference hall, but also writing an associated narrative and handouts, and anticipating the questions you are likely to encounter during the session. Each of these elements should be adapted to the audience, which may include people with different levels of familiarity with your topic and methods ( Nelson et al. 2002 ; Beilenson 2004 ). For example, the annual meeting of the American Public Health Association draws academics who conduct complex statistical analyses along with practitioners, program planners, policymakers, and journalists who typically do not.

Posters are a hybrid form—more detailed than a speech but less than a paper, more interactive than either ( Appendix A ). In a speech, you (the presenter) determine the focus of the presentation, but in a poster session, the viewers drive that focus. Different people will ask about different facets of your research. Some might do policy work or research on a similar topic or with related data or methods. Others will have ideas about how to apply or extend your work, raising new questions or suggesting different contrasts, ways of classifying data, or presenting results. Beilenson (2004) describes the experience of giving a poster as a dialogue between you and your viewers.

By the end of an active poster session, you may have learned as much from your viewers as they have from you, especially if the topic, methods, or audience are new to you. For instance, at David Snowdon's first poster presentation on educational attainment and longevity using data from The Nun Study, another researcher returned several times to talk with Snowdon, eventually suggesting that he extend his research to focus on Alzheimer's disease, which led to an important new direction in his research ( Snowdon 2001 ). In addition, presenting a poster provides excellent practice in explaining quickly and clearly why your project is important and what your findings mean—a useful skill to apply when revising a speech or paper on the same topic.

WRITING FOR A VARIED PROFESSIONAL AUDIENCE

Audiences at professional conferences vary considerably in their substantive and methodological backgrounds. Some will be experts on your topic but not your methods, some will be experts on your methods but not your topic, and most will fall somewhere in between. In addition, advances in research methods imply that even researchers who received cutting-edge methodological training 10 or 20 years ago might not be conversant with the latest approaches. As you design your poster, provide enough background on both the topic and the methods to convey the purpose, findings, and implications of your research to the expected range of readers.

Telling a Simple, Clear Story

Write so your audience can understand why your work is of interest to them, providing them with a clear take-home message that they can grasp in the few minutes they will spend at your poster. Experts in communications and poster design recommend planning your poster around two to three key points that you want your audience to walk away with, then designing the title, charts, and text to emphasize those points ( Briscoe 1996 ; Nelson et al. 2002 ; Beilenson 2004 ). Start by introducing the two or three key questions you have decided will be the focus of your poster, and then provide a brief overview of data and methods before presenting the evidence to answer those questions. Close with a summary of your findings and their implications for research and policy.

A 2001 survey of government policymakers showed that they prefer summaries of research to be written so they can immediately see how the findings relate to issues currently facing their constituencies, without wading through a formal research paper ( Sorian and Baugh 2002 ). Complaints that surfaced about many research reports included that they were “too long, dense, or detailed,” or “too theoretical, technical, or jargony.” On average, respondents said they read only about a quarter of the research material they receive for detail, skim about half of it, and never get to the rest.

To ensure that your poster is one viewers will read, understand, and remember, present your analyses to match the issues and questions of concern to them, rather than making readers translate your statistical results to fit their interests ( DiFranza and the Staff of the Advocacy Institute 1996 ; Nelson et al. 2002 ). Often, their questions will affect how you code your data, specify your model, or design your intervention and evaluation, so plan ahead by familiarizing yourself with your audience's interests and likely applications of your study findings. In an academic journal article, you might report parameter estimates and standard errors for each independent variable in your regression model. In the poster version, emphasize findings for specific program design features, demographic, or geographic groups, using straightforward means of presenting effect size and statistical significance; see “Describing Numeric Patterns and Contrasts” and “Presenting Statistical Test Results” below.

The following sections offer guidelines on how to present statistical findings on posters, accompanied by examples of “poor” and “better” descriptions—samples of ineffective writing annotated to point out weaknesses, accompanied by concrete examples and explanations of improved presentation. These ideas are illustrated with results from a multilevel analysis of disenrollment from the State Children's Health Insurance Program (SCHIP; Phillips et al. 2004 ). I chose that paper to show how to prepare a poster about a sophisticated quantitative analysis of a topic of interest to HSR readers, and because I was a collaborator in that study, which was presented in the three formats compared here—as a paper, a speech, and a poster.

Explaining Statistical Methods

Beilenson (2004) and Briscoe (1996) suggest keeping your description of data and methods brief, providing enough information for viewers to follow the story line and evaluate your approach. Avoid cluttering the poster with too much technical detail or obscuring key findings with excessive jargon. For readers interested in additional methodological information, provide a handout and a citation to the pertinent research paper.

As you write about statistical methods or other technical issues, relate them to the specific concepts you study. Provide synonyms for technical and statistical terminology, remembering that many conferences of interest to policy researchers draw people from a range of disciplines. Even with a quantitatively sophisticated audience, don't assume that people will know the equivalent vocabulary used in other fields. A few years ago, the journal Medical Care published an article whose sole purpose was to compare statistical terminology across various disciplines involved in health services research so that people could understand one another ( Maciejewski et al. 2002 ). After you define the term you plan to use, mention the synonyms from the various fields represented in your audience.

Consider whether acronyms are necessary on your poster. Avoid them if they are not familiar to the field or would be used only once or twice on your poster. If you use acronyms, spell them out at first usage, even those that are common in health services research such as “HEDIS®”(Health Plan Employer Data and Information Set) or “HLM”(hierarchical linear model).

Poor: “We use logistic regression and a discrete-time hazards specification to assess relative hazards of SCHIP disenrollment, with plan level as our key independent variable.” Comment: Terms like “discrete-time hazards specification” may be confusing to readers without training in those methods, which are relatively new on the scene. Also the meaning of “SCHIP” or “plan level” may be unfamiliar to some readers unless defined earlier on the poster.

Better: “Chances of disenrollment from the State Children's Health Insurance Program (SCHIP) vary by amount of time enrolled, so we used hazards models (also known as event history analysis or survival analysis) to correct for those differences when estimating disenrollment patterns for SCHIP plans for different income levels.” Comment: This version clarifies the terms and concepts, naming the statistical method and its synonyms, and providing a sense of why this type of analysis is needed.

To explain a statistical method or assumption, paraphrase technical terms and illustrate how the analytic approach applies to your particular research question and data:

Poor : “The data structure can be formulated as a two-level hierarchical linear model, with families (the level-1 unit of analysis) nested within counties (the level-2 unit of analysis).” Comment: Although this description would be fine for readers used to working with this type of statistical model, those who aren't conversant with those methods may be confused by terminology such as “level-1” and “unit of analysis.”

Better: “The data have a hierarchical (or multilevel) structure, with families clustered within counties.” Comment: By replacing “nested” with the more familiar “clustered,” identifying the specific concepts for the two levels of analysis, and mentioning that “hierarchical” and “multilevel” refer to the same type of analytic structure, this description relates the generic class of statistical model to this particular study.

Presenting Results with Charts

Charts are often the preferred way to convey numeric patterns, quickly revealing the relative sizes of groups, comparative levels of some outcome, or directions of trends ( Briscoe 1996 ; Tufte 2001 ; Nelson et al. 2002 ). As Beilenson puts it, “let your figures do the talking,” reducing the need for long text descriptions or complex tables with lots of tiny numbers. For example, create a pie chart to present sample composition, use a simple bar chart to show how the dependent variable varies across subgroups, or use line charts or clustered bar charts to illustrate the net effects of nonlinear specifications or interactions among independent variables ( Miller 2005 ). Charts that include confidence intervals around point estimates are a quick and effective way to present effect size, direction, and statistical significance. For multivariate analyses, consider presenting only the results for the main variables of interest, listing the other variables in the model in a footnote and including complex statistical tables in a handout.

Provide each chart with a title (in large type) that explains the topic of that chart. A rhetorical question or summary of the main finding can be very effective. Accompany each chart with a few annotations that succinctly describe the patterns in that chart. Although each chart page should be self-explanatory, be judicious: Tufte (2001) cautions against encumbering your charts with too much “nondata ink”—excessive labeling or superfluous features such as arrows and labels on individual data points. Strive for a balance between guiding your readers through the findings and maintaining a clean, uncluttered poster. Use chart types that are familiar to your expected audience. Finally, remember that you can flesh out descriptions of charts and tables in your script rather than including all the details on the poster itself; see “Narrative to Accompany a Poster.”

Describing Numeric Patterns and Contrasts

As you describe patterns or numeric contrasts, whether from simple calculations or complex statistical models, explain both the direction and magnitude of the association. Incorporate the concepts under study and the units of measurement rather than simply reporting coefficients (β's) ( Friedman 1990 ; Miller 2005 ).

Poor: “Number of enrolled children in the family is correlated with disenrollment.” Comment: Neither the direction nor the size of the association is apparent.

Poor [version #2]: “The log-hazard of disenrollment for one-child families was 0.316.” Comment: Most readers find it easier to assess the size and direction from hazards ratios (a form of relative risk) instead of log-hazards (log-relative risks, the β's from a hazards model).

Better: “Families with only one child enrolled in the program were about 1.4 times as likely as larger families to disenroll.” Comment: This version explains the association between number of children and disenrollment without requiring viewers to exponentiate the log-hazard in their heads to assess the size and direction of that association. It also explicitly identifies the group against which one-child families are compared in the model.

Presenting Statistical Test Results

On your poster, use an approach to presenting statistical significance that keeps the focus on your results, not on the arithmetic needed to conduct inferential statistical tests. Replace standard errors or test statistics with confidence intervals, p- values, or symbols, or use formatting such as boldface, italics, or a contrasting color to denote statistically significant findings ( Davis 1997 ; Miller 2005 ). Include the detailed statistical results in handouts for later perusal.

To illustrate these recommendations, Figures 1 and and2 2 demonstrate how to divide results from a complex, multilevel model across several poster pages, using charts and bullets in lieu of the detailed statistical table from the scientific paper ( Table 1 ; Phillips et al. 2004 ). Following experts' advice to focus on one or two key points, these charts emphasize the findings from the final model (Model 5) rather than also discussing each of the fixed- and random-effects specifications from the paper.

Presenting Complex Statistical Results Graphically

Text Summary of Additional Statistical Results

Multilevel Discrete-Time Hazards Models of Disenrollment from SCHIP, New Jersey, January 1998–April 2000

Source : Phillips et al. (2004) .

SCHIP, State Children's Health Insurance Program; LRH, log relative-hazard; SE, standard error.

Figure 1 uses a chart (also from the paper) to present the net effects of a complicated set of interactions between two family-level traits (race and SCHIP plan) and a cross-level interaction between race of the family and county physician racial composition. The title is a rhetorical question that identifies the issue addressed in the chart, and the annotations explain the pattern. The chart version substantially reduces the amount of time viewers need to understand the main take-home point, averting the need to mentally sum and exponentiate several coefficients from the table.

Figure 2 uses bulleted text to summarize other key results from the model, translating log-relative hazards into hazards ratios and interpreting them with minimal reliance on jargon. The results for family race, SCHIP plan, and county physician racial composition are not repeated in Figure 2 , averting the common problem of interpreting main effect coefficients and interaction coefficients without reference to one another.

Alternatively, replace the text summary shown in Figure 2 with Table 2 —a simplified version of Table 1 which presents only the results for Model 5, replaces log-relative hazards with hazards ratios, reports associated confidence intervals in lieu of standard errors, and uses boldface to denote statistical significance. (On a color slide, use a contrasting color in lieu of bold.)

Relative Risks of SCHIP Disenrollment for Other * Family and County Characteristics, New Jersey, January 1998–April 2000

Statistically significant associations are shown in bold.

Based on hierarchical linear model controlling for months enrolled, months-squared, race, SCHIP plan, county physician racial composition, and all variables shown here. Scaled deviance =30,895. Random effects estimate for between-county variance =0.005 (standard error =0.006). SCHIP, State Children's Health Insurance Program; 95% CI, 95% confidence interval.

CONTENTS AND ORGANIZATION OF A POSTER

Research posters are organized like scientific papers, with separate pages devoted to the objectives and background, data and methods, results, and conclusions ( Briscoe 1996 ). Readers view the posters at their own pace and at close range; thus you can include more detail than in slides for a speech (see Appendix A for a detailed comparison of content and format of papers, speeches, and posters). Don't simply post pages from the scientific paper, which are far too text-heavy for a poster. Adapt them, replacing long paragraphs and complex tables with bulleted text, charts, and simple tables ( Briscoe 1996 ; Beilenson 2004 ). Fink (1995) provides useful guidelines for writing text bullets to convey research results. Use presentation software such as PowerPoint to create your pages or adapt them from related slides, facilitating good page layout with generous type size, bullets, and page titles. Such software also makes it easy to create matching handouts (see “Handouts”).

The “W's” (who, what, when, where, why) are an effective way to organize the elements of a poster.

- In the introductory section, describe what you are studying, why it is important, and how your analysis will add to the existing literature in the field.

- In the data and methods section of a statistical analysis, list when, where, who, and how the data were collected, how many cases were involved, and how the data were analyzed. For other types of interventions or program evaluations, list who, when, where, and how many, along with how the project was implemented and assessed.

- In the results section, present what you found.

- In the conclusion, return to what you found and how it can be used to inform programs or policies related to the issue.

Number and Layout of Pages

To determine how many pages you have to work with, find out the dimensions of your assigned space. A 4′ × 8′ bulletin board accommodates the equivalent of about twenty 8.5″ × 11″ pages, but be selective—no poster can capture the full detail of a large series of multivariate models. A trifold presentation board (3′ high by 4′ wide) will hold roughly a dozen pages, organized into three panels ( Appendix B ). Breaking the arrangement into vertical sections allows viewers to read each section standing in one place while following the conventions of reading left-to-right and top-to-bottom ( Briscoe 1996 ).

- At the top of the poster, put an informative title in a large, readable type size. On a 4′ × 8′ bulletin board, there should also be room for an institutional logo.

Suggested Layout for a 4′ × 8′ poster.

- In the left-hand panel, set the stage for the research question, conveying why the topic is of policy interest, summarizing major empirical or theoretical work on related topics, and stating your hypotheses or project aims, and explaining how your work fills in gaps in previous analyses.

- In the middle panel, briefly describe your data source, variables, and methods, then present results in tables or charts accompanied by text annotations. Diagrams, maps, and photographs are very effective for conveying issues difficult to capture succinctly in words ( Miller 2005 ), and to help readers envision the context. A schematic diagram of relationships among variables can be useful for illustrating causal order. Likewise, a diagram can be a succinct way to convey timing of different components of a longitudinal study or the nested structure of a multilevel dataset.

- In the right-hand panel, summarize your findings and relate them back to the research question or project aims, discuss strengths and limitations of your approach, identify research, practice, or policy implications, and suggest directions for future research.

Figure 3 (adapted from Beilenson 2004 ) shows a suggested layout for a 4′ × 8′ bulletin board, designed to be created using software such as Pagemaker that generates a single-sheet presentation; Appendix C shows a complete poster version of the Phillips et al. (2004) multilevel analysis of SCHIP disenrollment. If hardware or budget constraints preclude making a single-sheet poster, a similar configuration can be created using standard 8.5″ × 11″ pages in place of the individual tables, charts, or blocks of text shown in Figure 3 .

Find out well in advance how the posters are to be mounted so you can bring the appropriate supplies. If the room is set up for table-top presentations, tri-fold poster boards are essential because you won't have anything to attach a flat poster board or pages to. If you have been assigned a bulletin board, bring push-pins or a staple gun.

Regardless of whether you will be mounting your poster at the conference or ahead of time, plan how the pages are to be arranged. Experiment with different page arrangements on a table marked with the dimensions of your overall poster. Once you have a final layout, number the backs of the pages or draw a rough sketch to work from as you arrange the pages on the board. If you must pin pages to a bulletin board at the conference venue, allow ample time to make them level and evenly spaced.

Other Design Considerations

A few other issues to keep in mind as you design your poster. Write a short, specific title that fits in large type size on the title banner of your poster. The title will be potential readers' first glimpse of your poster, so make it inviting and easy to read from a distance—at least 40-point type, ideally larger. Beilenson (2004) advises embedding your key finding in the title so viewers don't have to dig through the abstract or concluding page to understand the purpose and conclusions of your work. A caution: If you report a numeric finding in your title, keep in mind that readers may latch onto it as a “factoid” to summarize your conclusions, so select and phrase it carefully ( McDonough 2000 ).

Use at least 14-point type for the body of the poster text. As Briscoe (1996) points out, “many in your audience have reached the bifocal age” and all of them will read your poster while standing, hence long paragraphs in small type will not be appreciated! Make judicious use of color. Use a clear, white, or pastel for the background, with black or another dark color for most text, and a bright, contrasting shade to emphasize key points or to identify statistically significant results ( Davis 1997 ).

NARRATIVE TO ACCOMPANY A POSTER

Prepare a brief oral synopsis of the purpose, findings, and implications of your work to say to interested parties as they pause to read your poster. Keep it short—a few sentences that highlight what you are studying, a couple of key findings, and why they are important. Design your overview as a “sound byte” that captures your main points in a succinct and compelling fashion ( Beilenson 2004 ). After hearing your introduction, listeners will either nod and move along or comment on some aspect of your work that intrigues them. You can then tailor additional discussion to individual listeners, adjusting the focus and amount of detail to suit their interests. Gesture at the relevant pages as you make each point, stating the purpose of each chart or table and explaining its layout before describing the numeric findings; see Miller (2005) for guidelines on how to explain tables and charts to a live audience. Briscoe (1996) points out that these mini-scripts are opportunities for you to fill in details of your story line, allowing you to keep the pages themselves simple and uncluttered.

Prepare short answers to likely questions about various aspects of your work, such as why it is important from a policy or research perspective, or descriptions of data, methods, and specific results. Think of these as little modules from an overall speech—concise descriptions of particular elements of your study that you can choose among in response to questions that arise. Beilenson (2004) also recommends developing a few questions to ask your viewers, inquiring about their reactions to your findings, ideas for additional questions, or names of others working on the topic.

Practice your poster presentation in front of a test audience acquainted with the interests and statistical proficiency of your expected viewers. Ideally, your critic should not be too familiar with your work: A fresh set of eyes and ears is more likely to identify potential points of confusion than someone who is jaded from working closely with the material while writing the paper or drafting the poster ( Beilenson 2004 ). Ask your reviewer to identify elements that are unclear, flag jargon to be paraphrased or defined, and recommend changes to improve clarity ( Miller 2005 ). Have them critique your oral presentation as well as the contents and layout of the poster.

Prepare handouts to distribute to interested viewers. These can be produced from slides created in presentation software, printed several to a page along with a cover page containing the abstract and your contact information. Or package an executive summary or abstract with a few key tables or charts. Handouts provide access to the more detailed literature review, data and methods, full set of results, and citations without requiring viewers to read all of that information from the poster ( Beilenson 2004 ; Miller 2005 ). Although you also can bring copies of the complete paper, it is easier on both you and your viewers if you collect business cards or addresses and mail the paper later.

The quality and effectiveness of research posters at professional conferences is often compromised by authors' failure to take into account the unique nature of such presentations. One common error is posting numerous statistical tables and long paragraphs from a research paper—an approach that overwhelms viewers with too much detail for this type of format and presumes familiarity with advanced statistical techniques. Following recommendations from the literature on research communication and poster design, this paper shows how to focus each poster on a few key points, using charts and text bullets to convey results as part of a clear, straightforward story line, and supplementing with handouts and an oral overview.

Another frequent mistake is treating posters as a one-way means of communication. Unlike published papers, poster sessions are live presentations; unlike speeches, they allow for extended conversation with viewers. This note explains how to create an oral synopsis of the project, short modular descriptions of poster elements, and questions to encourage dialog. By following these guidelines, researchers can substantially improve their conference posters as vehicles to disseminate findings to varied research and policy audiences.

CHECKLIST FOR PREPARING AND PRESENTING AN EFFECTIVE RESEARCH POSTERS

- Design poster to focus on two or three key points.

- Adapt materials to suit expected viewers' knowledge of your topic and methods.

- Design questions to meet their interests and expected applications of your work.

- Paraphrase descriptions of complex statistical methods.

- Spell out acronyms if used.

- Replace large detailed tables with charts or small, simplified tables.

- Accompany tables or charts with bulleted annotations of major findings.

- Describe direction and magnitude of associations.

- Use confidence intervals, p -values, symbols, or formatting to denote statistical significance.

Layout and Format

- Organize the poster into background, data and methods, results, and study implications.

- Divide the material into vertical sections on the poster.

- Use at least 14-point type in the body of your poster, at least 40-point for the title.

Narrative Description

- Rehearse a three to four sentence overview of your research objectives and main findings.

- Summary of key studies and gaps in existing literature

- Data and methods

- Each table, chart, or set of bulleted results

- Research, policy, and practice implications

- Solicit their input on your findings

- Develop additional questions for later analysis

- Identify other researchers in the field

- Prepare handouts to distribute to interested viewers.

- Print slides from presentation software, several to a page.

- Or package an executive summary or abstract with a few key tables or charts.

- Include an abstract and contact information.

Acknowledgments

I would like to thank Ellen Idler, Julie Phillips, Deborah Carr, Diane (Deedee) Davis, and two anonymous reviewers for helpful comments on earlier drafts of this work.

Supplementary Material

The following supplementary material for this article is available online:

APPENDIX A.1. Comparison of Research Papers, Presentations, and Posters—Materials and Audience Interaction.

Suggested Layout for a Tri-Fold Presentation Board.

Example Research Poster of Phillips et al. 2004 Study.

- Beilenson J. Developing Effective Poster Presentations. Gerontology News. 2004; 32 (9):6–9. [ Google Scholar ]

- Briscoe MH. Preparing Scientific Illustrations: A Guide to Better Posters, Presentations, and Publications. 2. New York: Springer-Verlag; 1996. [ Google Scholar ]

- Davis M. Scientific Papers and Presentations. New York: Academic Press; 1997. [ Google Scholar ]

- DiFranza JR. A Researcher's Guide to Effective Dissemination of Policy-Related Research. Princeton, NJ: The Robert Wood Johnson Foundation; 1996. the Staff of the Advocacy Institute, with Assistance from the Center for Strategic Communications. [ Google Scholar ]

- Fink A. How to Report on Surveys. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications; 1995. [ Google Scholar ]

- Friedman GD. Be Kind to Your Reader. American Journal of Epidemiology. 1990; 132 (4):591–3. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Maciejewski ML, Diehr P, Smith MA, Hebert P. Common Methodological Terms in Health Services Research and Their Symptoms. Medical Care. 2002; 40 :477–84. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- McDonough J. Experiencing Politics: A Legislator's Stories of Government and Health Care. Berkeley: University of California Press; 2000. [ Google Scholar ]

- Miller JE. The Chicago Guide to Writing about Multivariate Analysis. Chicago Guides to Writing, Editing and Publishing. Chicago: University of Chicago Press; 2005. [ Google Scholar ]

- Nelson DE, Brownson RC, Remington PL, Parvanta C, editors. Communicating Public Health Information Effectively: A Guide for Practitioners. Washington, DC: American Public Health Association; 2002. [ Google Scholar ]

- Phillips JA, Miller JE, Cantor JC, Gaboda D. Context or Composition. What Explains Variation in SCHIP Disenrollment? Health Services Research. 2004; 39 (4, part I):865–8. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Snowdon D. Aging with Grace: What the Nun Study Teaches Us about Leading Longer, Healthier, and More Meaningful Lives. New York: Bantam Books; 2001. [ Google Scholar ]

- Sorian R, Baugh T. Power of Information Closing the Gap between Research and Policy. Health Affairs. 2002; 21 (2):264–73. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Tufte ER. The Visual Display of Quantitative Information. 2. Cheshire, CT: Graphics Press; 2001. [ Google Scholar ]

Purdue Online Writing Lab Purdue OWL® College of Liberal Arts

Conference Presentations

Welcome to the Purdue OWL

This page is brought to you by the OWL at Purdue University. When printing this page, you must include the entire legal notice.

Copyright ©1995-2018 by The Writing Lab & The OWL at Purdue and Purdue University. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, reproduced, broadcast, rewritten, or redistributed without permission. Use of this site constitutes acceptance of our terms and conditions of fair use.

This resource provides a detailed overview of the common types of conference papers and sessions graduate students can expect, followed by pointers on presenting conference papers for an audience.

Types of conference papers and sessions

Panel presentations are the most common form of presentation you will encounter in your graduate career. You will be one of three to four participants in a panel or session (the terminology varies depending on the organizers) and be given fifteen to twenty minutes to present your paper. This is often followed by a ten-minute question-and-answer session either immediately after your presentation or after all of the speakers are finished. It is up to the panel organizer to decide upon this framework. In the course of the question-and-answer session, you may also address and query the other panelists if you have questions yourself. Note that you can often propose a conference presentation by yourself and be sorted onto a panel by conference organizers, or you can propose a panel with a group of colleagues. Self-proposed panels typically have more closely related topics than conference-organized panels.

Roundtables feature an average of five to six speakers, each of whom gets the floor for approximately five to ten minutes to speak on their respective topics and/or subtopics. At times, papers from the speakers might be circulated in advance among the roundtable members or even prospective attendees.

Workshops feature one or a few organizers, who usually give a brief presentation but spend the majority of the time for the session facilitating an activity that attendees will do. Some common topics for these sessions typically include learning a technology or generating some content, such as teaching materials.

Lightning talks (or Ignite talks, or Pecha Kucha talks) are very short presentations where presenters' slide decks automatically advance after a few seconds; most individual talks are no longer than 5 minutes, and a lightning talk session typically invites 10 or more presenters to participate over the course of an hour or two rather than limiting the presenters like a panel presentation. A lightning talk session will sometimes be held as a sort of competition where attendees can vote for the best talk.

SIGs (Special Interest Groups) are groups of scholars focused on a particular smaller topic within the purview of the larger conference. The structure of these sessions varies by conference and even by group, but in general they tend to be structured either more like a panel presentation, with presenters and leaders, or more like a roundtable, with several speakers and a particular meeting agenda. These styles resemble, respectively, a miniconference focusing on a particular topic and a committee meeting.

Papers with respondents are structured around a speaker who gives an approximately thirty-minute paper and a respondent who contributes their own thoughts, objections, and further questions in the following fifteen minutes. Finally, the speaker gets that same amount of time to formulate their reply to the respondent.