- Prospective Student

- Accepted Undergraduate Student

- Current Student

- Alumnus or Alumna

- Student Life

- Academic Calendars

- Academic Calendars Are Temporarily Unavailable

- Graduate Programs

- Online Programs

- Program Directory

- Undergraduate

- Center for Accessibility Services and Academic Accommodations

- Peer Mentor Program

- Services for Distance and Online Students

- AIC Core Education (ACE) Program

- AIC Plan For Excellence (APEX)

- CASAA current students

- CASAA new students

- Contact Us CASAA

- Course Catalogs

Credit Hours Calculator

- Disability Law

- Information Technology

- Institutional Review Board

- Lost Password

- Non Degree programs

- Noonan Tutoring Center

- Noonan Tutoring Services

- Occupational Therapy Student Resources

- Academic Regulations

- Cooperating Colleges of Greater Springfield

- Course Offerings

- Credit Hour Policy

- Early College Program FAQ

- Family Educational Rights and Privacy Act (FERPA)

- Registrar FAQ

- Reduced Summer Tuition for Undergraduate Students

- Reset Password

- Student Success Advising

- The Innovation and Media Hive

- Tutoring Program FAQ

- Request REACH Information

- Services and Pricing

- Student Testimonials

What is a Credit Hour?

AIC uses the industry-standard Carnegie Unit to define credit hours for both traditional and distance courses.

Each credit hour corresponds to a minimum of 3 hours of student engagement per week for a traditional 14-week course or 6 hours per week for a 7-week course. This time may be spent on discussions, readings and lectures, study and research, and assignments.

Most courses at AIC are three credit hours.

© 2024 American International College

How Much Time Do College Students Spend on Homework

by Jack Tai | Oct 9, 2019 | Articles

Does college life involve more studying or socializing?

Find out how much time college students need to devote to their homework in order to succeed in class.

We all know that it takes hard work to succeed in college and earn top grades.

To find out more about the time demands of studying and learning, let’s review the average homework amounts of college students.

HowtoLearn.com expert, Jack Tai, CEO of OneClass.com shows how homework improves grades in college and an average of how much time is required.

How Many Hours Do College Students Spend on Homework?

Classes in college are much different from those in high school.

For students in high school, a large part of learning occurs in the classroom with homework used to support class activities.

One of the first thing that college students need to learn is how to read and remember more quickly. It gives them a competitive benefit in their grades and when they learn new information to escalate their career.

Taking a speed reading course that shows you how to learn at the same time is one of the best ways for students to complete their reading assignments and their homework.

However, in college, students spend a shorter period in class and spend more time learning outside of the classroom.

This shift to an independent learning structure means that college students should expect to spend more time on homework than they did during high school.

In college, a good rule of thumb for homework estimates that for each college credit you take, you’ll spend one hour in the classroom and two to three hours on homework each week.

These homework tasks can include readings, working on assignments, or studying for exams.

Based upon these estimates, a three-credit college class would require each week to include approximately three hours attending lectures and six to nine hours of homework.

Extrapolating this out to the 15-credit course load of a full-time student, that would be 15 hours in the classroom and 30 to 45 hours studying and doing homework.

These time estimates demonstrate that college students have significantly more homework than the 10 hours per week average among high school students. In fact, doing homework in college can take as much time as a full-time job.

Students should keep in mind that these homework amounts are averages.

Students will find that some professors assign more or less homework. Students may also find that some classes assign very little homework in the beginning of the semester, but increase later on in preparation for exams or when a major project is due.

There can even be variation based upon the major with some areas of study requiring more lab work or reading.

Do College Students Do Homework on Weekends?

Based on the quantity of homework in college, it’s nearly certain that students will be spending some of their weekends doing homework.

For example, if each weekday, a student spends three hours in class and spends five hours on homework, there’s still at least five hours of homework to do on the weekend.

When considering how homework schedules can affect learning, it’s important to remember that even though college students face a significant amount of homework, one of the best learning strategies is to space out study sessions into short time blocks.

This includes not just doing homework every day of the week, but also establishing short study blocks in the morning, afternoon, and evening. With this approach, students can avoid cramming on Sunday night to be ready for class.

What’s the Best Way to Get Help with Your Homework?

In college, there are academic resources built into campus life to support learning.

For example, you may have access to an on-campus learning center or tutoring facilities. You may also have the support of teaching assistants or regular office hours.

That’s why OneClass recommends a course like How to Read a Book in a Day and Remember It which gives a c hoice to support your learning.

Another choice is on demand tutoring.

They send detailed, step-by-step solutions within just 24 hours, and frequently, answers are sent in less than 12 hours.

When students have on-demand access to homework help, it’s possible to avoid the poor grades that can result from unfinished homework.

Plus, 24/7 Homework Help makes it easy to ask a question. Simply snap a photo and upload it to the platform.

That’s all tutors need to get started preparing your solution.

Rather than retyping questions or struggling with math formulas, asking questions and getting answers is as easy as click and go.

Homework Help supports coursework for both high school and college students across a wide range of subjects. Moreover, students can access OneClass’ knowledge base of previously answered homework questions.

Simply browse by subject or search the directory to find out if another student struggled to learn the same class material.

Related articles

NEW COURSE: How to Read a Book in a Day and Remember It

Call for Entries Parent and Teacher Choice Awards. Winners Featured to Over 2 Million People

All About Reading-Comprehensive Instructional Reading Program

Parent & Teacher Choice Award Winner – Letter Tracing for Kids

Parent and Teacher Choice Award Winner – Number Tracing for Kids ages 3-5

Parent and Teacher Choice Award winner! Cursive Handwriting for Kids

One Minute Gratitude Journal

Parent and Teacher Choice Award winner! Cursive Handwriting for Teens

Make Teaching Easier! 1000+ Images, Stories & Activities

Prodigy Math and English – FREE Math and English Skills

Recent Posts

- 5 Essential Techniques to Teach Sight Words to Children

- 7 Most Common Reading Problems and How to Fix Them

- Best Program for Struggling Readers

- 21 Interactive Reading Strategies for Pre-Kindergarten

- 27 Education Storybook Activities to Improve Literacy

Recent Comments

- Glenda on How to Teach Spelling Using Phonics

- Dorothy on How to Tell If You Are an Employee or Entrepreneur

- Pat Wyman on 5 Best Focus and Motivation Tips

- kapenda chibanga on 5 Best Focus and Motivation Tips

- Jennifer Dean on 9 Proven Ways to Learn Anything Faster

College Homework: What You Need to Know

- April 1, 2020

Samantha "Sam" Sparks

- Future of Education

Despite what Hollywood shows us, most of college life actually involves studying, burying yourself in mountains of books, writing mountains of reports, and, of course, doing a whole lot of homework.

Wait, homework? That’s right, homework doesn’t end just because high school did: part of parcel of any college course will be homework. So if you thought college is harder than high school , then you’re right, because in between hours and hours of lectures and term papers and exams, you’re still going to have to take home a lot of schoolwork to do in the comfort of your dorm.

College life is demanding, it’s difficult, but at the end of the day, it’s fulfilling. You might have had this idealized version of what your college life is going to be like, but we’re here to tell you: it’s not all parties and cardigans.

How Many Hours Does College Homework Require?

Here’s the thing about college homework: it’s vastly different from the type of takehome school activities you might have had in high school.

See, high school students are given homework to augment what they’ve learned in the classroom. For high school students, a majority of their learning happens in school, with their teachers guiding them along the way.

In college, however, your professors will encourage you to learn on your own. Yes, you will be attending hours and hours of lectures and seminars, but most of your learning is going to take place in the library, with your professors taking a more backseat approach to your learning process. This independent learning structure teaches prospective students to hone their critical thinking skills, perfect their research abilities, and encourage them to come up with original thoughts and ideas.

Sure, your professors will still step in every now and then to help with anything you’re struggling with and to correct certain mistakes, but by and large, the learning process in college is entirely up to how you develop your skills.

This is the reason why college homework is voluminous: it’s designed to teach you how to basically learn on your own. While there is no set standard on how much time you should spend doing homework in college, a good rule-of-thumb practiced by model students is 3 hours a week per college credit . It doesn’t seem like a lot, until you factor in that the average college student takes on about 15 units per semester. With that in mind, it’s safe to assume that a single, 3-unit college class would usually require 9 hours of homework per week.

But don’t worry, college homework is also different from high school homework in how it’s structured. High school homework usually involves a take-home activity of some kind, where students answer certain questions posed to them. College homework, on the other hand, is more on reading texts that you’ll discuss in your next lecture, studying for exams, and, of course, take-home activities.

Take these averages with a grain of salt, however, as the average number of hours required to do college homework will also depend on your professor, the type of class you’re attending, what you’re majoring in, and whether or not you have other activities (like laboratory work or field work) that would compensate for homework.

Do Students Do College Homework On the Weekends?

Again, based on the average number we provided above, and again, depending on numerous other factors, it’s safe to say that, yes, you would have to complete a lot of college homework on the weekends.

Using the average given above, let’s say that a student does 9 hours of homework per week per class. A typical semester would involve 5 different classes (each with 3 units), which means that a student would be doing an average of 45 hours of homework per week. That would equal to around 6 hours of homework a day, including weekends.

That might seem overwhelming, but again: college homework is different from high school homework in that it doesn’t always involve take-home activities. In fact, most of your college homework (but again, depending on your professor, your major, and other mitigating factors) will probably involve doing readings and writing essays. Some types of college homework might not even feel like homework, as some professors encourage inter-personal learning by requiring their students to form groups and discuss certain topics instead of doing take-home activities or writing papers. Again, lab work and field work (depending on your major) might also make up for homework.

Remember: this is all relative. Some people read fast and will find that 3 hours per unit per week is much too much time considering they can finish a reading in under an hour.The faster you learn how to read, the less amount of time you’ll need to devote to homework.

College homework is difficult, but it’s also manageable. This is why you see a lot of study groups in college, where your peers will establish a way for everyone to learn on a collective basis, as this would help lighten the mental load you might face during your college life. There are also different strategies you can develop to master your time management skills, all of which will help you become a more holistic person once you leave college.

So, yes, your weekends will probably be chock-full of schoolwork, but you’ll need to learn how to manage your time in such a way that you’ll be able to do your homework and socialize, but also have time to develop your other skills and/or talk to family and friends.

College Homework Isn’t All That Bad, Though

Sure, you’ll probably have time for parties and joining a fraternity/sorority, even attend those mythical college keggers (something that the person who invented college probably didn’t have in mind). But I hate to break it to you: those are going to be few and far in between. But here’s a consolation, however: you’re going to be studying something you’re actually interested in.

All of those hours spent in the library, writing down papers, doing college homework? It’s going to feel like a minute because you’re doing something you actually love doing. And if you fear that you’ll be missing out, don’t worry: all those people that you think are attending those parties aren’t actually there because they, too, will be busy studying!

About the Author

News & Updates

How to clean a leather couch, legal 101 the process of serving subpoena, why is learning through play important at home, too.

Time Management Calculator

Students often believe they do not have enough time to study for exams, participate in extracurriculars, have jobs, and have a social life. Students often plan their day and then use the leftover time to study. If you plan your priority activities first (i.e. eating, sleeping, studying, working, etc.), you will still have time to do everything else that you want to do. This time calculator will help you understand how you are organizing your time throughout the week.

- Enter the number of credits you are taking. The calculator will then automatically calculate your class and study time. This calculation is based on the idea that for every hour you are in class, you should spend about 2-3 hours studying outside of class. You can adjust this if you believe you are taking a class that requires less than this ratio but we encourage students to consider budgeting this amount of time first.

- Enter the number of hours you spend on other activities. The calculator assumes that you will be getting 8 hours of sleep each night. This should remain the same! Getting enough sleep is one of the most important things you can do to improve your time management.

- Based on your results adjust your time as needed to achieve a positive and sustainable work/life balance. Small changes can help you organize your time more efficiently!

How Much Homework is Too Much?

When redesigning a course or putting together a new course, faculty often struggle with how much homework and readings to assign. Too little homework and students might not be prepared for the class sessions or be able to adequately practice basic skills or produce sufficient in-depth work to properly master the learning goals of the course. Too much and some students may feel overwhelmed and find it difficult to keep up or have to sacrifice work in other courses.

A common rule of thumb is that students should study three hours for each credit hour of the course, but this isn’t definitive. Universities might recommend that students spend anywhere from two or three hours of study or as much as six to nine hours of study or more for each course credit hour. A 2014 study found that, nationwide, college students self reported spending about 17 hours each week on homework, reading and assignments. Studies of high school students show that too much homework can produce diminishing returns on student learning, so finding the right balance can be difficult.

There are no hard and fast rules about the amount of readings and homework that faculty assign. It will vary according to the university, the department, the level of the classes, and even other external factors that impact students in your course. (Duke’s faculty handbook addresses many facets of courses, such as absences, but not the typical amount of homework specifically.)

To consider the perspective of a typical student that might be similar to the situations faced at Duke, Harvard posted a blog entry by one of their students aimed at giving students new to the university about what they could expect. There are lots of readings, of course, but time has to be spent on completing problem sets, sometimes elaborate multimedia or research projects, responding to discussion posts and writing essays. Your class is one of several, and students have to balance the needs of your class with others and with clubs, special projects, volunteer work or other activities they’re involved with as part of their overall experience.

The Rice Center for Teaching Excellence has some online calculators for estimating class workload that can help you get a general understanding of the time it may take for a student to read a particular number of pages of material at different levels or to complete essays or other types of homework.

To narrow down your decision-making about homework when redesigning or creating your own course, you might consider situational factors that may influence the amount of homework that’s appropriate.

Connection with your learning goals

Is the homework clearly connected with the learning goals of your students for a particular class session or week in the course? Students will find homework beneficial and valuable if they feel that it is meaningful . If you think students might see readings or assignments as busy work, think about ways to modify the homework to make a clearer connection with what is happening in class. Resist the temptation to assign something because the students need to know it. Ask yourself if they will actually use it immediately in the course or if the material or exercises should be relegated to supplementary material.

Levels of performance

The type of readings and homework given to first year students will be very different from those given to more experienced individuals in higher-level courses. If you’re unsure if your readings or other work might be too easy (or too complex) for students in your course, ask a colleague in your department or at another university to give feedback on your assignment. If former students in the course (or a similar course) are available, ask them for feedback on a sample reading or assignment.

Common practices

What are the common practices in your department or discipline? Some departments, with particular classes, may have general guidelines or best practices you can keep in mind when assigning homework.

External factors

What type of typical student will be taking your course? If it’s a course preparing for a major or within an area of study, are there other courses with heavy workloads they might be taking at the same time? Are they completing projects, research, or community work that might make it difficult for them to keep up with a heavy homework load for your course?

Students who speak English as a second language, are first generation students, or who may be having to work to support themselves as they take courses may need support to get the most out of homework. Detailed instructions for the homework, along with outlining your learning goals and how the assignment connects the course, can help students understand how the readings and assignments fit into their studies. A reading guide, with questions prompts or background, can help students gain a better understanding of a reading. Resources to look up unfamiliar cultural references or terms can make readings and assignments less overwhelming.

If you would like more ideas about planning homework and assignments for your course or more information and guidance on course design and assessment, contact Duke Learning Innovation to speak with one of our consultants .

Time Managment Calculator

Time management.

How much time should you be studying per week? Research suggests that students should spend approximately 2-3 hours, per credit hour, studying in order to be successful in their courses. STEM classes often require 3-4 hours, per credit hour, of studying to be successful.

- Think about how you normally study. Where do you study? What time of the day do you prefer to study?

- Consider using the Intense Study Session/Pomodoro Technique . Take a break every 40-45 minutes, walk around your room, or stretch to help keep you motivated.

- Do you review the lecture material immediately after class? Doing this give the best chance for retaining the information and understanding the material.

Procrastination

- Do you tend to put assignments, reading or prepping for an exam off until the last minute?

- Do you always end up cramming for exams at 3am.? Do you always find yourself doing an "all-nighter"?

- Are you feeling like you can never get enough sleep and don't have time for recreation or student activities?

If this sounds like YOU,you may be suffering from: PROCRASTINATION

It's a common student disorder affecting up to 75-95% of students which, if left to run unchecked, may result in missed assignments, low grades, stress and poor mental health.

Time Management Calculator

Sometimes the simple act of writing down and planning out how your time is being spent each day, helps you determine different ways to more efficiently manage your time. This time management calculator may help you manage your time more efficiently. (Adapted from the University of Connecticut)

Instructions

- Each question is asking you to submit an average

- You must answer the questions in order.

- Insert your "Hours Per Day" for Questions 01-05 and click "Multiply" for each.

- Next, insert your "Hours Per Week" for Questions 06-09.

- Click "Add" to total your "Hours Per Week" for all activities (except studying).

- Faculty Associates

- Our Partners

- Academic Events

- Certificate in University Teaching

- Classroom Support

- Consultations

- Course & Curriculum Design

- Learning Communities

- Peer Support of Teaching

- Support for Scholarship of Teaching and Learning

- Video and Design

- ACUE Courses

- Event & Workshop Calendar

- GTA Orientation

- New Faculty Orientation

- Sessions by Demand

- Video Catalog

- Writing Effective Learning Outcomes

- WVU Course Delivery Rubric

- WVU Course Design Rubric

- QM Resources

- QM Training

- Submit a Course for QM Review

- Course Contingency Planning

- Go2Knowledge

- Magna Digital Library

- General Resources

- University Testing Center

- Tutoring Centers

- SpeakWrite Writing Studio

- Mental Health Resources

- Online Students Resources

- Student Success

- Syllabus Builder

- Syllabus Policies and Statements

- iClicker Cloud

- TLC Beckley

Credit Hours and Time Equivalencies

The general rule provided by the U.S. Department of Education and regional accreditors is that one academic credit hour is composed of 15 hours of direct instruction (50-60 minute hours) and 30 hours of out-of-class student work (60-minute hours). This means that a student spends 45 total hours of time on 1 credit, and 135 total hours (45 hours of direct instruction and 90 hours of out-of-class student work) over the course of a semester in a typical 3 credit class. Time per week calculations for various course lengths can be found further down the page.

There can be nuances in the way this is applied depending on the type of course you are delivering. For online courses, one must distinguish between direct instruction and student work “outside the classroom,” see below. For study abroad courses, student work expectations are replaced with cultural engagement time. In experiential courses, the distinction between direct instruction and out-of-class time is dropped altogether and the time is combined to become 45 hours per credit. (See the WVU Catalog credit hour definitions for more details.)

When working with online and hybrid courses, it can become difficult to distinguish direct instruction from student work “outside the classroom.” The TLC provides the following basic guidance.

“Direct instruction” includes:

- In-class lecture (for hybrid courses)

- Text in a learning module

- Video (instructor or departmentally created)

- Video from other sources (equivalent to a guest speaker or a movie watched during class time)

- Multimedia interaction (learning objects)

- Discussions, blogs, wikis

- Exams and quizzes

- Any instructor-guided activity including small group activities

- Any assignment or activity you would traditionally do “in-class”

“Out-of-class student work” includes:

- Videos or podcasts created by authors other than the instructor intended to replace readings

- Prep of presentations

- Group work that traditionally would be done “outside of class”

Estimating how much time an activity or reading will take can be tricky. There are numerous course workload estimators available on the web, as well as websites that offer tables of time equivalencies for common activities. Students may also participate at different speeds, so start with a good base and refine your content and activities over time.

In accordance with federal regulations, online distance education courses are required to have regular and substantive instructor-initiated interactions, which will include both direct instruction and student work. All students in a course should have similar opportunities for instructor interaction, which is particularly important for courses with a mix of on-site and distance students like HyFlex.

See our page on substantive interaction for more information.

Incorporating active learning in online and hybrid courses may make it more difficult to map “in-class” time to traditional categories of “direct instruction.” However, instructor-led activity, or group work centered around instructional activities (active learning), would also be appropriate to count as class time, in contrast to student work outside of class, and in many cases could also fulfill the regular and substantive instructor-initiated interaction requirements. The above lists are not exhaustive.

If you are exploring this topic you can also request TLC assistance .

Course Time Per Week

The amount of time that should be offered in a course per week will vary with the length of the course.

Time per week over 15 weeks:

1 Credit Course: 1 hr direct instruction, 2 hrs student work 3 Credit Course: 3 hrs direct instruction, 6 hrs student work

Time per week over 8 weeks:

1 Credit Course: ~2 hrs direct instruction, 4 hrs student work 3 Credit Course: ~6 hrs direct instruction, 12 hrs student work

Time per week over 6 weeks:

1 Credit Course: 2.5 hrs direct instruction, 5 hrs student work 3 Credit Course: 7.5 hrs direct instruction, 15 hrs student work

Time per week over 5 weeks (see the section on Compressed Courses below):

1 Credit Course: 3 hrs direct instruction, 6 hrs student work 3 Credit Course: 9 hrs direct instruction, 18 hrs student work

Time per week over 3 weeks (see the section on Compressed Courses below):

1 Credit Course: 5 hrs direct instruction, 10 hrs student work 3 Credit Course: 15 hrs direct instruction, 30 hrs student work

Compressed Courses

Courses less than 6 weeks may be eligible to be delivered as compressed format courses. Compressed format courses must be marked as such in CIM Courses , must contain sufficient content for students to meet the course outcomes, must have regular and substantive instructor-initiated interaction, must use the same or similar key assessments as standard format courses, but do not need to meet the typical time-based credit hour requirements. These courses receive higher assessment scrutiny from the Department of Education and thus the Provost’s Office, and are required to show comparison student performance data to standard deliveries of the course.

Correspondence Courses

Correspondence courses have similar assessment requirements to compressed courses but do not need to meet the requirements for regular and substantive instructor-initiated interaction. See the WVU catalog on Modality Definitions for more information.

Code of Federal Regulations: Chapter 34, §600.2 .

WVU Catalog: Credit Hour Definition

WVU Catalog: Modality Definitions

WVU College of Law: Determination of Credit Hours Worked

RICE: Workload Estimator (calculator)

Penn State: Hours of Instructional Activity Equivalents (HIA) for Undergraduate Courses

- Accreditations

- Web Standards

- Privacy Notice

- Questions or Comments?

© 2024 West Virginia University. WVU is an EEO/Affirmative Action employer — Minority/Female/Disability/Veteran. Last updated on December 22, 2021.

- A-Z Site Index

- WVU Careers

- WVU on Facebook

- WVU on Twitter

- WVU on YouTube

- College Prep & Testing

- College Search

- Applications & Admissions

- Alternatives to 4-Year College

- Orientation & Move-In

- Campus Involvement

- Campus Resources

- Homesickness

- Diversity & Inclusion

- Transferring

- Residential Life

- Finding an Apartment

- Off-Campus Life

- Mental Health

- Alcohol & Drugs

- Relationships & Sexuality

- COVID-19 Resources

- Paying for College

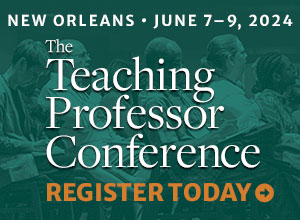

- Banking & Credit

- Success Strategies

- Majors & Minors

- Study Abroad

- Diverse Learners

- Online Education

- Internships

- Career Services

- Graduate School

- Graduation & Celebrations

- First Generation

- Shop for College

- Academics »

Student Study Time Matters

Vicki nelson.

Most college students want to do well, but they don’t always know what is required to do well. Finding and spending quality study time is one of the first and most important skills that your student can master, but it's rarely as simple as it sounds.

If a student is struggling in class, one of the first questions I ask is, “How much time do you spend studying?”

Although it’s not the only element, time spent studying is one of the basics, so it’s a good place to start. Once we examine time, we can move on to other factors such as how, where, what and when students are studying, but we start with time .

If your student is struggling , help them explore how much time they are spending on schoolwork.

How Much Is Enough?

Very often, a student’s answer to how much time they spend hitting the books doesn’t match the expectation that most professors have for college students. There’s a disconnect about “how much is enough?”

Most college classes meet for a number of “credit hours” – typically 3 or 4. The general rule of thumb (and the definition of credit hour adopted by the Department of Education) is that students should spend approximately 2–3 hours on outside-of-class work for each credit hour or hour spent in the classroom.

Therefore, a student taking five 3-credit classes spends 15 hours each week in class and should be spending 30 hours on work outside of class , or 45 hours/week total.

When we talk about this, I can see on students’ faces that for most of them this isn’t even close to their reality!

According to one survey conducted by the National Survey of Student Engagement, most college students spend an average of 10–13 hours/week studying, or less than 2 hours/day and less than half of what is expected. Only about 11% of students spend more than 25 hours/week on schoolwork.

Why Such a Disconnect?

Warning: math ahead!

It may be that students fail to do the math – or fail to flip the equation.

College expectations are significantly different from the actual time that most high school students spend on outside-of-school work, but the total picture may not be that far off. In order to help students understand, we crunch some more numbers.

Most high school students spend approximately 6 hours/day or 30 hours/week in school. In a 180 day school year, students spend approximately 1,080 hours in school. Some surveys suggest that the average amount of time that most high school students spend on homework is 4–5 hours/week. That’s approximately 1 hour/day or 180 hours/year. So that puts the average time spent on class and homework combined at 1,260 hours/school year.

Now let’s look at college: Most semesters are approximately 15 weeks long. That student with 15 credits (5 classes) spends 225 hours in class and, with the formula above, should be spending 450 hours studying. That’s 675 hours/semester or 1,350 for the year. That’s a bit more than the 1,260 in high school, but only 90 hours, or an average of 3 hours more/week.

The problem is not necessarily the number of hours, it's that many students haven’t flipped the equation and recognized the time expected outside of class.

In high school, students’ 6-hour school day was not under their control but they did much of their work during that time. That hour-or-so a day of homework was an add-on. (Some students definitely spend more than 1 hour/day, but we’re looking at averages.)

In college, students spend a small number of hours in class (approximately 15/week) and are expected to complete almost all their reading, writing and studying outside of class. The expectation doesn’t require significantly more hours; the hours are simply allocated differently – and require discipline to make sure they happen. What students sometimes see as “free time” is really just time that they are responsible for scheduling themselves.

Help Your Student Adjust to College Academics >

How to Fit It All In?

Once we look at these numbers, the question that students often ask is, “How am I supposed to fit that into my week? There aren’t enough hours!”

Again: more math.

I remind students that there are 168 hours in a week. If a student spends 45 hours on class and studying, that leaves 123 hours. If the student sleeps 8 hours per night (few do!), that’s another 56 hours which leaves 67 hours, or at least 9.5 hours/day for work or play.

Many colleges recommend that full-time students should work no more than 20 hours/week at a job if they want to do well in their classes and this calculation shows why.

Making It Work

Many students may not spend 30 or more hours/week studying, but understanding what is expected may motivate them to put in some additional study time. That takes planning, organizing and discipline. Students need to be aware of obstacles and distractions (social media, partying, working too many hours) that may interfere with their ability to find balance.

What Can My Student Do?

Here are a few things your student can try.

- Start by keeping a time journal for a few days or a week . Keep a log and record what you are doing each hour as you go through your day. At the end of the week, observe how you have spent your time. How much time did you actually spend studying? Socializing? Sleeping? Texting? On social media? At a job? Find the “time stealers.”

- Prioritize studying. Don’t hope that you’ll find the time. Schedule your study time each day – make it an appointment with yourself and stick to it.

- Limit phone time. This isn’t easy. In fact, many students find it almost impossible to turn off their phones even for a short time. It may take some practice but putting the phone away during designated study time can make a big difference in how efficient and focused you can be.

- Spend time with friends who study . It’s easier to put in the time when the people around you are doing the same thing. Find an accountability partner who will help you stay on track.

- If you have a job, ask if there is any flexibility with shifts or responsibilities. Ask whether you can schedule fewer shifts at prime study times like exam periods or when a big paper or project is due. You might also look for an on-campus job that will allow some study time while on the job. Sometimes working at a computer lab, library, information or check-in desk will provide down time. If so, be sure to use it wisely.

- Work on strengthening your time management skills. Block out study times and stick to the plan. Plan ahead for long-term assignments and schedule bite-sized pieces. Don’t underestimate how much time big assignments will take.

Being a full-time student is a full-time job. Start by looking at the numbers with your student and then encourage them to create strategies that will keep them on task.

With understanding and practice, your student can plan for and spend the time needed to succeed in college.

Get stories and expert advice on all things related to college and parenting.

Table of Contents

- Rhythm of the First Semester

- Tips from a Student on Making It Through the First Year

- Who Is Your First‑Year Student?

- Campus Resources: Your Cheat Sheet

- Handling Roommate Issues

- Study Time Matters

- The Importance of Professors and Advisors

- Should My Student Withdraw from a Difficult Course?

- Essential Health Conversations

- A Mental Health Game Plan for College Students and Families

- Assertiveness is the Secret Sauce

- Is Your Student at Risk for an Eating Disorder?

- Learning to Manage Money

- 5 Ways to Begin Career Prep in the First Year

- The Value of Outside Opportunities

Housing Timeline

Don't Miss Out!

Get engaging stories and helpful information all year long. Join our college parent newsletter!

Powerful Personality Knowledge: How Extraverts and Introverts Learn Differently

College Preparedness: Recovering from the Pandemic

College Reality Check

How Many Credits is Too Much for a College Semester

After deciding which institutions to add to your college list and choosing which school to pick after getting a handful of acceptance letters, it’s time to figure out which classes to take and how many. And an integral part of this critical moment is figuring out how many credits you should take.

Most colleges and universities with a semester system recommend 15 credits per semester, which amounts to 30 credits per year. Full-time students are enrolled in at least 12 credits and a maximum of 18 credits per semester. The right number of credits to take per semester is on a case-to-case basis.

In order to get your hands on a bachelor’s degree, you must complete a total of 120 credits.

Deciding the number of credits to take per semester is a matter that’s not just about whether or not you will be able to graduate from college on time. It’s about many other things too, such as those that have something to do with scholarships or grants or whether you will be balancing college and work or looking after your kids.

How Many Hours is One Credit Equivalent To?

Simply put, one credit is equivalent to one hour spent inside a classroom per week. So, in other words, a three-credit course (most undergraduate courses are three credits each) is equivalent to three hours spent inside a classroom per week. One credit also entails two hours of homework per week.

The number of credits you enroll in per semester will determine the number of hours you will have to spend inside a classroom — the more credits you take, the more classes you have to attend.

When doing the math, it’s not just the hours of classroom work per credit you should take into account.

It’s also a must that you factor in the number of hours of homework per credit required — learning academic courses does not begin and end inside a classroom. As a matter of fact, per credit, you will have to devote more time to doing homework than listening to your professor per week.

Considering both classes and homework, one credit is equivalent to three hours of studying. That’s one hour of classroom work and two hours of studying at home or in your dorm.

Here are the formulas for calculating the number of hours you will have to spend per week and per semester:

- (Number of credits x 3 hours) = total study hours per week

- (Number of credits x 3 hours) x (15 weeks per semester) = total study hours per semester

Based on the formulas given above, students who enroll in 15 credits per semester spend around 45 hours on studying and around 675 hours on studying per semester — that’s around 27% of the entire week or semester!

While one credit will always be equivalent to one hour of classroom work per week, unfortunately, one credit doesn’t necessarily mean two hours of homework per year. This matter is subjective in that it will depend on the type of learner you are and the difficulty of the course.

For instance, the general education course Math and the Engineering major pre-requisite course Calculus 1 are both three-credit courses. However, you will surely have to spend more time on the latter!

It goes without saying that deciding the number of credits to take per semester is not as easy as many students would like to think it is. Other than the fact that different courses have different difficulty levels despite having the exact same number of credits, there are also a handful of other things to take into account when deciding on a particular number.

And this takes us to this pressing question…

Factors to Consider When Deciding the Number of Credits

There are many factors to take into account when deciding how many credits to enroll in per semester. Leading the list is the number that students can realistically take, as determined by their lives outside the campus. There are also considerations such as school requirements and aid stipulations.

Knowing the right number of credits to take is important not only for first-time, first-year students but also for students from other year levels when enrolling every semester.

Here are some of the things to keep in mind before you settle on a particular number of credits:

College timetable

Do you want to become a bachelor’s degree holder in four years? Then opt for 15 credits per semester, which is equivalent to 30 credits per academic year. More than 60% of students at public and private institutions graduate in six years, and a common reason for it is taking the minimum or below the minimum number of credits per semester.

Needless to say, the more credits you complete per semester, the faster you will graduate from college.

Thinking about going for an accelerated program in order to graduate from college at a much faster rate? Then it’s a must that you complete the required number of credits per semester, which can be 18 credits or more.

Full-time vs. part-time

Most colleges and universities define full-time students as students enrolled in at least 12 credits per semester. It goes without saying that they define part-time students as those enrolled in less than 12 credits per semester.

Refrain from assuming that part-time students, since they take fewer credits per semester, do not graduate on time. Some of them, for instance, may be part-time students as a result of transfer credits. Still, the majority of part-time students usually graduate in six years — or sometimes longer.

Financial aid

First things first: both full-time and part-time college students are eligible for federal financial aid.

So, if you are planning on becoming a part-time student, fret not as you may still get monetary help from the government — the US Department of Education stipulates that you only have to be enrolled half-time in order to qualify, which is equivalent to at least six credits per semester.

However, there are scholarships and grants that students may lose if they go from being full-time students to part-time students. This is when the importance of carefully reading terms and conditions comes in.

Traditional vs. non-traditional

According to the National Center for Education Statistics (NCES), you are considered a non-traditional student if you are a part-time college student. So, in other words, if you enroll in less than 12 credits per semester, you will automatically become a non-traditional student — well, at least in the eyes of NCES.

Whether you are a traditional or non-traditional student can impact your decision credit-wise.

But just because students are regarded as non-traditional ones doesn’t mean right away that they are taking fewer credits per semester than anyone else.

For instance, online college students, which are non-traditional students, may enroll in 15 credits per semester or more, thus allowing them to earn a bachelor’s degree in four years or less.

Related Article: Is an Online College Degree Worth It?

Just Before You Enroll in a Certain Number of Credits

Students can choose anywhere from 12 credits to 18 credits per semester. They can take fewer than 12 credits or more than 18 credits per semester, although, in most instances, they will have to get permission beforehand.

But getting your hands on a permit to do so is not enough.

When figuring out how many credits to enroll in per semester, consider important deciding factors such as your school or program’s requirements, financial aid’s stipulations and personal life’s demands.

Related Questions

Are credits and credit hours the same?

Credits and credit hours are one and the same. Some colleges and universities may prefer “credit”, while others may prefer “credit hours”. Both credits and credit hours refer to the number of hours a student will spend in a course. For instance, a three-credit course is equivalent to three hours spent in the classroom.

Do credits have an expiration date?

Credits earned in college are good for life. So, in other words, they do not expire. However, it’s possible for some credits to not transfer into a program after several years. That’s because it’s not uncommon for academic programs to undergo some changes, causing some credits from certain courses to become valueless.

Read Also: 40 Ways to Save Money in College

Independent Education Consultant, Editor-in-chief. I have a graduate degree in Electrical Engineering and training in College Counseling. Member of American School Counselor Association (ASCA).

Similar Posts

40 Ways to Save Money in College: Conventional and Nonconventional

How to Get Straight A’s in High School: Secrets of an Overachiever Exposed

What to Bring to a College Dorm: Checklist

How Much Free Time Do You Have in College? More Than You Think

How to Have Fun in College Without Compromising Your Grades

How Much Does a College Dorm Cost?

Time on Task in Online Courses

Understanding how time “works” in online teaching and course design is often a challenge for online instructors, especially those new to online education. Four distinct yet related questions can express the challenge:

- How do I determine the total time on task (per week and for the entire course) expected of students in my online course?

- How can I calculate how much time students will actually need to complete the course assignments, assessments, and other tasks?

- What should students be doing with their time to effectively and efficiently accomplish the goals and learning outcomes for my online course?

- What should I be doing with my time as an online instructor?

Let us address each of these questions in turn.

Determining Time on Task in Online Education

The academic credit model, developed on the Carnegie unit over 100 years ago, is based on classroom hours for students and corresponding contact hours for faculty. Online courses appear not to fit this model, as by definition they do not have face-to-face classroom/seat time. The consensus within U.S. higher education is that one college credit requires 15 hours of classroom time plus additional homework time for students (typically two or three hours per hour of classroom time). How can this model accommodate courses that have no seat time?

The answer to this question is to de-emphasize the course mode or "delivery" method (online, F2F, blended, hybrid, HyFlex, etc.) and focus instead on total time on task (by course and/or week). This is the approach taken by the New York State Education Department, Office of College and University Evaluation, in its current policies for distance/online learning. The relevant section is worth quoting in full:

Time on task is the total learning time spent by a student in a college course, including instructional time as well as time spent studying and completing course assignments (e.g., reading, research, writing, individual and group projects.) Regardless of the delivery method or the particular learning activities employed, the amount of learning time in any college course should meet the guideline of the Carnegie unit, a total of 45 hours for one semester credit (in conventional classroom education this breaks down into 15 hours of instruction plus 30 hours of student work/study out of class.) "Instruction" is provided differently in online courses than in classroom-based courses. Despite the difference in methodology and activities, however, the total "learning time" online can usually be counted. Rather than try to distinguish between "in-class" and "outside-class" time for students, the faculty member developing and/or teaching the online course should calculate how much time a student doing satisfactory work would take to complete the work of the course, including: Reading course presentations/ "lectures" Reading other materials Participation in online discussions Doing research Writing papers or other assignments Completing all other assignments (e.g. projects) The total time spent on these tasks should be roughly equal to that spent on comparable tasks in a classroom-based course. Time spent downloading or uploading documents, troubleshooting technical problems, or in chat rooms (unless on course assignments such as group projects) should not be counted. In determining the time on task for an online course, useful information include: The course objectives and expected learning outcomes The list of topics in the course outline or syllabus; the textbooks, additional readings, and related education materials (such as software) required Statements in course materials informing students of the time and/or effort they are expected to devote to the course or individual parts of it A listing of the pedagogical tools to be used in the online course, how each will be used, and the expectations for participation (e.g., in an online discussion, how many substantive postings will be required of a student for each week or unit?) Theoretically, one should be able to measure any course, regardless of delivery method, by the description of content covered. However, this is difficult for anyone other than the course developer or instructor to determine accurately, since the same statement of content (in a course outline or syllabus) can represent many different levels of breadth and depth in the treatment of that content, and require widely varying amounts of time.

In sum, regardless of course mode or type of learning activities assigned, the total amount of student time on task for any RIT course (on-campus, online, independent study, capstone, etc.) should total 45 hours per credit/contact hour. To get the total number of time-on-task hours, multiply 45 times the number of credits. For a 3-credit course, for instance, that works out to 135 hours total. In practical terms, the 45 hours per credit is a minimum recommendation, as many programs at RIT and elsewhere expect more time on task per credit hour.

The hours per week vary depending upon the length (in weeks) of the course. See Figure 1 below for a breakdown of the time on task for RIT’s 3-credit course formats. To get the time-on-task hours per week, divide the total hours per course by the number of weeks. For a 1-week online course, for example, the instructor and/or course developer knows that students can expect to spend a minimum of 9 hours per week on course work.

Calculating the Time Needed To Complete Specific Online Tasks

The above guidelines from the New York State Education Department address how to determine not only total time on task, but also the time needed to complete specific learning tasks. For a variety of factors, it is far more challenging to determine the latter than the former. One of the biggest factors, of course, is student variability in ability, experience, and motivation. Nonetheless, the higher education literature does offer at least four viable methods for calculating completion times for learning tasks in any course mode:

- The experiential method. The least studied, but probably the most common method. As McDaniel (2011) wrote, “Faculty can use their experience to estimate the time and effort needed by the typical student to engage successfully in each of the learning activities in a particular field, course, and program…Using these estimates, the designers of courses determine if students have the requisite time to meet course expectations.”

- The proxy method. Similar to the experiential method, but with a formula. Here the instructor and/or course designer first calculates how much time it takes them to complete a given task, and this figure is then multiplied by some factor. As Carnegie Mellon University (2013) explains to their faculty, “To calculate how long it will take students to read an article or complete an assignment, you can estimate that your students will take three to four times longer to read than it takes you.”

- The survey method. Involves surveying students after they have completed a given task. Carnegie Mellon University (2013) advises faculty “to ask students how long it took them to do various assignments, and use this information in future course planning.”

- The “workload estimator” tool . Built by an award-winning team originally at Rice University, but now at the Wake Forest University’s Center for Teaching Excellence (Wake Forest University, 2021), instructors at any university can use this online tool to calculate “completion times” for Reading, Writing, and Exams along a continuum of variables, including page density, number of new concepts, difficulty, and purpose.

Learning Time for Students in Online Courses

Having addressed the determination of time on task, and the calculation of completion times for learning tasks, let us move on to the matter of what students can and should be doing with their time to effectively and efficiently accomplish the goals and learning outcomes for their online courses.

Despite some significant differences in communication technologies and pedagogical methods, online courses are similar to on-campus courses in many important respects. As we have seen, total time on task is the same for online and on-campus courses of equal lengths. Additionally, an online course will have the identical goals and learning outcomes as its on-campus counterpart. The online course must be equal in content and challenge as the on-campus course (Vai & Sosulski, 2011).

How students spend their time in on-campus and online courses is directly related to the assignments, assessments, and other tasks given by instructors. In the classroom portion of on-campus courses , students typically do some of the following activities:

- Listen to and take notes on lectures, presentations, and multimedia.

- Participate in whole-class and small-group discussions with other students and the instructor.

- Engage in experiential learning activities, such as labs, studios, field trips, and simulations.

- Practice developing new competencies.

- Take quizzes or exams.

- Write short in-class essays.

Students typically do the following as outside-class activities in on-campus courses :

- Read articles and books.

- Review class notes.

- Solve homework problems.

- Conduct and write-up research.

- Complete projects and other major assignments.

- Prepare classroom presentations.

- Meet with instructor during their office hours.

The same categories of learning tasks or activities exist in both course modes, though online instructors usually modify the on-campus activities to make best use of online communication technologies and pedagogies. It should be noted that on-campus instructors are increasing incorporating online learning tools and methods into their courses. Here are several representative samples of on-campus learning activities that have been modified for the online learning environment:

- An asynchronous video lecture may be an instructor’s commentary on the readings, with some links to illustrative images, media, or text.

- Small-group work may be a quick breakout in a synchronous web meeting or an extended discussion in the asynchronous discussion.

- Experiential learning activities can be virtual labs, in-person interviews, activities within the community, and actual or virtual field trips.

- Either the synchronous web meeting or the whole-class asynchronous discussion area will allow the instructor to expand upon the lecture. It also facilitates post-lecture Q & A and general student interaction.

As these samples suggest, online teaching and design (especially in asynchronous formats) incorporates and, at the same time, changes the discrete on-campus activities. The online lecture is both lecture and reading. Individual time and effort spent in small-group work is visible and persistent (unlike face-to-face group work) and consists of research, reading, and writing. Experiential learning activities include student reports back to the instructor and/or the entire class. Whole-class online discussion is reading, writing, and (ideally) instructor-to-student and peer-to-peer feedback/review.

Example Tasks and Completion Times for One Week of an Online Course

Here is an example of one week (9 hours) of learning tasks or activities and respective completion times for a 15-week, 3-credit course:

- Three, 15-minute chunked lectures (text or video) that cover one course topic each; links to illustrative web resources are included in each mini-lecture (1 hour).

- Assume that students spend additional time to review these lectures and explore the links to web resources (1/2 hour).

- Assign readings (1 hour).

- Require students to complete a ten-item online quiz to check their understanding of key terms and concepts from the readings and lectures (1 hour).

- Assign a discussion topic on a contemporary issue with a triple-layer response requirement (i.e., original post, responses to other classmates’ posts, responses to responses) (2 hours).

- Stipulate that small groups meet in their web-conferencing “room” and/or asynchronous discussion area to work on an iterative deliverable for their group project; for example, discussing and producing an outline of their final report (1 and 1/2 hour).

- Work on final research paper/project and presentation, which are due at the end of the course (2 hours).

Instructional Time for Faculty in Online Courses

The following (Vai & Sosulski, 2011) is most likely how an instructor spends their time in an asynchronous online course, assuming they are both designing and teaching or “delivering” the course:

- Designing the course and creating/curating the course materials . This is typically accomplished before the course begins, and therefore not counted in calculating online teaching time.

- Posting new information after the course has been fully designed and is “live.” In response to contemporary events and student needs/interests, the instructor is putting up announcements with just-in-time videos, calling attention to relevant material outside the course shell, posting commentaries on the discussions and other activities in the course, etc., as needed.

- Checking in on student interactions, participation, and questions about the course. This most typically happens in a dedicated discussion area (i.e., a Q & A or Ask the Instructor discussion forum), but also in email and in other ways and “places” online, such as blogs, wikis, web-conferencing meetings, etc.

- Giving feedback on assignments. Activities such as providing written comments (along with grades) when using the grade book, and giving more extensive written feedback on student worked that is posted to the assignment tool in the course.

- Class management . Includes activities such as sending out reminders of assignments that are due, grouping/pairing of students for team projects, and introducing new assignments and requirements.

Carnegie Mellon University, 2013. Solve a teaching problem: Assign a reasonable amount of work . Retrieved Dec. 2, 2021.

McDaniel, E. A. (2011). Level of student effort should replace contact time in course design. Journal of Information Technology Education , 10(10).

Vai, M. & Sosulski, K. (2011). Essentials of online course design: A standards-based guide . New York and London: Routledge.

Wake Forest University, 2021. Workload estimator 2.0 . Retrieved Dec. 2, 2021.

- Teaching and Learning

Questioning the Two-Hour Rule for Studying

- August 28, 2017

- Lolita Paff, PhD

F aculty often tell students to study two hours for every credit hour. Where and when did this rule of thumb originate? I’ve been unable to track down its genesis. I suspect it started around 1909, when the Carnegie Unit (CU) was accepted as the standard measure of class time. [See Heffernan (1973) and Shedd (2003) for thorough histories of the credit hour.] The U.S. Department of Education defines the credit hour as “One hour of classroom or direct faculty instruction and a minimum of two hours of out of class student work each week for approximately fifteen weeks for one semester…” The expectation was the norm when I was in college in the 1980s and more seasoned professors indicate it was expected in the 1970s too.

Is the two-hour rule relevant today? Why two hours? Why not one? Or three? Study resources and tools have changed dramatically in the past century. Typing papers, researching, and collaborating required a lot more time in prior decades. Personal computers, mobile devices, and the Internet have dramatically changed what goes on in and out of class, yet the two-hour rule persists.

What should be done during study time? Of bigger concern than the emphasis on time is the lack of direction about what to do during those hours. Some schools (Binghamton University, is one) require that course syllabi state what students might do outside of class, “completing assigned readings, studying for tests and examinations, participating in lab sessions, preparing written assignments, and other course-related tasks.” That’s a start, but it’s not enough.

Before we blame students by saying they should already know what to do, let’s consider an example. I studied classical piano for a dozen years. Each week the teacher would instruct on notation, technique, and interpretation. Lessons always included detailed descriptions and a discussion of what I was to do during practice. How long I was to practice was only an estimate. The emphasis was on what needed to be done, not how long it would take. Practice time consisted of warm-up exercises, scales, and work on compositions. I didn’t always practice diligently (sorry, Mrs. Farr), but I consistently knew what I should be doing during practice to improve as a pianist.

Can most students say the same? A statement on the syllabus, particularly one that emphasizes policies, probably doesn’t get much attention from students during study time. Likewise, a teacher’s admonition to “study X hours per week” is easily forgotten or ignored. In addition, we lose credibility with our students if we tell them to “study two hours per credit” for no other reason than that’s the way it’s always been done. We should be more concerned with outcomes than time.

Shift focus from time to task. I recognize that telling students to study doesn’t mean it will happen. I’m also not suggesting everything students do outside of class should be graded. But instead of telling students how long to study, emphasize mastery. Provide examples of active learning strategies so they can use their time more effectively. In addition to active reading assignments and graded homework, the following activities promote engagement and go beyond students’ typical study strategies, such as creating note cards or “looking over” their notes.

- Practice Problems: Provide extra, ungraded problems. Suggest they mix different types of problems to simulate an exam. Ask them to solve problems they’ve created. Provide additional problems and hold back the solutions to allow students some time to work without the answers. Consider incorporating a couple of these questions on exams to motivate practice.

- Rewrite Notes in Your Own Words: Rewrites are an opportunity to “replay” what was said and done in class. Be intentional about asking students if they have questions about what they’ve written in their notes. Occasionally set aside a couple of minutes in class for students to compare notes and seek clarification.

- Concept Maps: Students can use note cards to accomplish deep understanding if they try to connect single pieces of information on each card to other concepts through a concept map. These can be drawn by hand or created with software. Emphasize substance over form. The purpose is to make connections and see the content from different perspectives (Berry & Chew, 2008).

- Respond to Learning Reflection Prompts: How is X related to Y? What other information would you want to find? What was the most challenging topic in the chapter? How does this material connect to what you learned before? Reflection prompts promote connections across topics, helping students see content more holistically. Incorporate reflection in graded work as appropriate. Reflection assignments can be independent and ungraded or incorporated in class or online.

- Quiz to Learn: Provide sample questions or ask students to create multiple-choice questions as part of their study activities. Occasionally use one or two student-created questions on exams, or reward exceptional examples with extra credit.

- Crib Sheets: Even if they’re not allowed during an exam, the process of identifying what to put on a “cheat” sheet and organizing the information promotes thinking about the relative importance and relationships among concepts. Set aside a few minutes of class time for students to compare and contrast their sheets as part of student-led exam review.

I think it’s time to retire the two-hour rule. For many students, studying is something only done before an exam and homework is completed because it’s graded. If we want to develop self-directed learners, these narrow conceptions of what it means to “study” must change. Teachers broaden and reshape students’ perceptions of homework and study by de-emphasizing time and focusing on substance. We can help students see class time, study time, and homework as an integrated system of activities designed to advance learning. We do that by being as specific and intentional about structuring students’ out-of-class study activities, graded or otherwise, as we are about what goes on during class.

References: Berry, J.W. & Chew, S.L. (2008). Improving Learning Through Interventions of Student-Generated Questions and Concept Maps. Teaching of Psychology, 35: 305-312.

Binghamton University Syllabus Policy. https://www.binghamton.edu/academics/provost/faculty-staff-handbook/handbook-vii.html#A8 Accessed: July 26, 2017.

Heffernan, J.M. (1973). The Credibility of the Credit Hour: The History, Use and Shortcomings of the Credit System. The Journal of Higher Education , 44(1): 61-72.

Shedd, J.M. (2003). The History of the Student Credit Hour, New Directions for Higher Education, 122 (Summer): 3-12.

US Department of Education Credit Hour Definition. https://www.ecfr.gov/cgi-bin/text-idx?rgn=div8&node=34:3.1.3.1.1.1.23.2 Accessed: July 26, 2017

Dr. Lolita Paff is an associate professor of business and economics at Penn State Berks. She also serves on the advisory board of the Teaching Professor Conference.

Stay Updated with Faculty Focus!

Get exclusive access to programs, reports, podcast episodes, articles, and more!

- Opens in a new tab

Welcome Back

Username or Email

Remember Me

Already a subscriber? log in here.

Module 7: Learning Strategies

Class-time to study-time ratio, learning outcomes.

- Describe typical ratios of in-class to out-of-class work per credit hour and how to effectively schedule your study time

Class-Time and Study-Time Ratios

After Kai decides to talk to his guidance counselor about his stress and difficulty balancing his activities, his guidance counselor recommends that Kai create a schedule. This schedule will help him set time for homework, studying, work, and leisure activities so that he avoids procrastinating on his schoolwork. His counselor explains that if Kai sets aside specific time to study every day—rather than simply studying when he feels like he has the time—his study habits will become more regular, which will improve Kai’s learning.

At the end of their session, Kai and his counselor have put together a rough schedule for Kai to further refine as he goes through the next couple of weeks.

Although Kai knows that studying is important and he is trying to keep up with homework, he really needs to work on time management. This skill is challenging for many college students, especially ones with lots of responsibilities outside of school. Unlike high school classes, college classes meet less often and college students are expected to do more independent learning, homework, and studying.

You might have heard that the ratio of classroom time to study time should be one to two or one to three. This ratio would mean that for every hour you spend in class, you should plan to spend two to three hours out of class working independently on course assignments. If your composition class meets for one hour, three times a week, you’d be expected to devote from six to nine hours each week on reading assignments, writing assignments, etc.

However, it’s important to keep in mind that the one-to-two or one-to-three time ratio is generally more appropriate for semester-long courses of eighteen weeks. More and more institutions of higher learning are moving away from semesters to terms ranging from eight to sixteen weeks long.

The recommended class-time to study-time ratio might change depending on the course (how rigorous it is and how many credits it’s worth), the institution’s expectations, the length of the school term, and the frequency with which a class meets. For example, if you’re used to taking classes on a quarter system of ten weeks, but then you start taking courses over an eight-weeks period, you may need to spend more time studying outside of class since you’re trying to learn the same amount of information in a shorter term period. You may also find that if one of the courses you’re taking is worth one-and-a-half credit hours but the rest of your courses are worth one credit hour each, you may need to put in more study hours for your one-and-a-half credit hours course. Finally, if you’re taking a course that only meets once a week such as a writing workshop, you may consider putting in more study and reading time in between class meetings than the general one-to-two or one-to-three ratio.

If you account for all the classes you’re taking in a given semester, the study time really adds up—and if it sounds like a lot of work, it is! Remember, this schedule is temporary while you’re in school. The only way to stay on top of the workload is by creating a schedule to help you manage your time. You might decide to use a weekly or monthly schedule—or both. Whatever you choose, the following tips can help you design a smart schedule that’s easy to follow and stick with.

Start with Fixed Time Commitments

First off, mark down the commitments that don’t allow any flexibility. These include class meetings, work hours, appointments, etc. Capturing the fixed parts of your schedule can help you see where there are blocks of time that can be used for other activities.

Kai’s Schedule

Kai is taking four classes: Spanish 101, U.S. History, College Algebra, and Introduction to Psychology. He also has a fixed work schedule—he works 27 hours a week.

Consider Your Studying and Homework Habits

When are you most productive? Are you a morning person or a night owl? Block out your study times accordingly. You’ll also want to factor in any resources you might need. For instance, if you prefer to study very early or late in the day, and you’re working on a research paper, you might want to check the library hours to make sure it’s open when you need it.

Since Kai’s Spanish class starts his schedule at 9:00 a.m. every day, Kai decides to use that as the base for his schedule. He doesn’t usually have trouble waking up in the mornings (except for on the weekends), so he decides that he can do a bit of studying before class. His Spanish practice is often something he can do while eating or traveling, so this gives him a bit of leniency with his schedule.

Kai’s marked work in grey, classes in green, and dedicated study time in yellow:

Even if you prefer weekly over monthly schedules, write reminders for yourself and keep track of any upcoming projects, papers, or exams. You will also want to prepare for these assignments in advance. Most students eventually discover (the hard way) that cramming for exams the night before and waiting till the last minute to start on a term paper is a poor strategy. Procrastination creates a lot of unnecessary stress, and the resulting final product—whether an exam, lab report, or paper—is rarely your best work. Try simple things to break down large tasks, such as setting aside an hour or so each day to work on them during the weeks leading up to the deadline. If you get stuck, get help from your instructor early, rather than waiting until the day before an assignment is due.

Schedule Leisure Time

It might seem impossible to leave room in your schedule for fun activities, but every student needs and deserves to socialize and relax on a regular basis. Try to make this time something you look forward to and count on, and use it as a reward for getting things done. You might reserve every Friday or Saturday evening for going out with friends, for example. Perhaps your children have sporting events or special occasions you want to make time for. Try to reschedule your study time so you have enough time to study and enough time to do things outside of school that you want to do.

When you look at Kai’s schedule, you can see that he’s left Friday, Saturday, and Sunday evenings open. While he plans on using Sundays to complete larger assignments when he needs to, he’s left his Friday and Saturday evenings open for leisure.

time ratio: in an academic context, this refers to the number of hours a student should plan to work for each hour spent in a scheduled class

- College Success. Authored by : Jolene Carr. Provided by : Lumen Learning. License : CC BY: Attribution

- Six Tips for College Health and Safety. Provided by : Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Located at : http://www.cdc.gov/features/collegehealth/ . License : Public Domain: No Known Copyright

Table of Contents

- Credit Hour Definition

- Course Proposals and Changes

- Credit Hour Reviews

- Office of Assessment and Planning

- Office of the Associate Academic Vice President – Undergraduate Studies

Implementing Procedures

- University Curriculum Handbook

Related Policies

- Academic Credit, Grades, and Records Policy

- Internships Policy

- Registration Policy

- Tuition and Fees Policy

Contents, Related Policies, Applicability ▾

This policy defines a credit hour and describes the processes designed to assure that the definition is followed throughout the university.

The university measures academic credit in credit hours. In accordance with federal regulations, a credit hour for all courses and programs at the university is an amount of work represented in intended learning outcomes and verified by evidence of student achievement that reasonably approximates not less than: