Because differences are our greatest strength

The 13 disability categories under IDEA

How do kids qualify for special education? Learn about the 13 disability categories and other important details about Individualized Education Programs (IEPs).

By Julie Rawe

Expert reviewed by Rayma Griffin, MA, MEd

Updated April 9, 2024

What are the 13 disability categories in special education ? And why do they matter?

To qualify for services, kids need to have a disability that impacts their schooling. The Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA) groups disabilities into 13 categories. But this doesn’t mean the law only covers 13 disabilities . Some of the categories cover a wide range of challenges.

IDEA disability categories

To get an Individualized Education Program (IEP), kids need to meet the requirements for at least one category. Keep reading to learn about the 13 disability categories and why all of them require finding that the disability “adversely affects” a child’s education.

1. Specific learning disability (SLD)

This category covers a wide range of learning challenges. These include differences that make it hard to read, write, listen, speak, reason, or do math. Here are some common examples of specific learning disabilities (SLD):

Dyscalculia

Written expression disorder (you may also hear this referred to as dysgraphia)

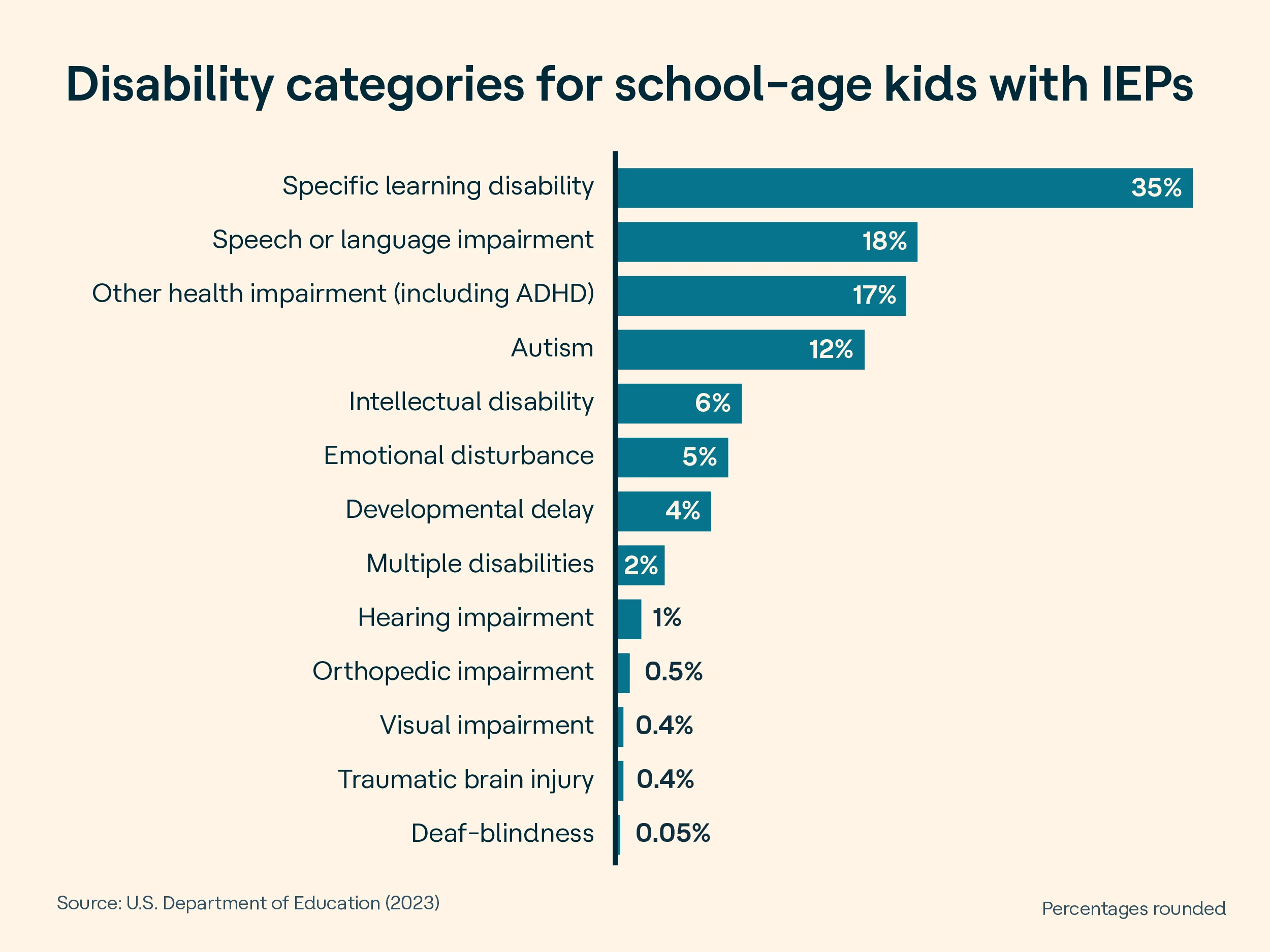

This is by far the most common category in special education. The numbers vary a bit from year to year. But students with learning disabilities tend to make up about a third of all students who have IEPs. In the 2020–21 school year, around 35 percent of students who had IEPs qualified under this category.

2. Speech or language impairment

This is the second most common category in special education. A lot of kids have IEPs for speech impediments. Common examples include lisping and stuttering.

Language disorders can be covered in this category too. Or they can be covered in the learning disability category. These disorders make it hard for kids to understand words or express themselves.

3. Other health impairment

This is another commonly used category. It covers a wide range of conditions that may limit a child’s strength, energy, or alertness. One example is ADHD . Many kids who qualify for an IEP under this category have attention deficits.

Other examples in this category include epilepsy, sickle cell anemia, and Tourette syndrome.

4. Autism spectrum disorder (ASD)

ASD is a common developmental disability. It affects social and communication skills. It can also impact behavior.

5. Intellectual disability

This category covers below-average intellectual ability. Kids with Down syndrome often qualify for special education under this category.

6. Emotional disturbance

This category covers mental health issues. Examples include anxiety disorder, bipolar disorder, and oppositional defiant disorder. (Some emotional or conduct disorders may also be covered under “other health impairment.”)

7. Developmental delay

This category can be used for young kids who are late in meeting developmental milestones like walking and talking.

Different states have different rules about this category. It’s also the only category in IDEA that has an age limit. It can’t be used after age 9.

8. Multiple disabilities

Many kids have more than one disability, such as ADHD and autism. But this category is only used when the combination of disabilities requires a highly specialized approach, such as intellectual disability and blindness.

9. Hearing impairment, including deafness

This category includes a range of hearing issues that can be permanent or that can change over time. (This category does not include auditory processing disorder , which is considered a learning disability.)

10. Orthopedic impairment

This category covers issues with bones, joints, and muscles. One example is cerebral palsy.

11. Visual impairment, including blindness

This category covers a range of vision problems, including partial sight and blindness. But if eyewear can correct a vision problem, then a child wouldn’t qualify for special education under this category.

12. Traumatic brain injury

This category covers brain injuries that happen at some point after a child is born. These can be caused by things like being shaken as a baby or hitting your head in an accident.

13. Deaf-blindness

This category covers kids with severe hearing and vision loss. Their communication challenges are so unique that programs for just the deaf or blind can’t meet their needs.

What “adversely affects” means

Kids need to have a disability to qualify for special education. But IDEA says schools must also find that the disability “adversely affects” a child’s performance in school. This means it has to have a negative impact on how the student is doing in school.

Learn how schools decide if a child is eligible for special education .

Primary disability category

When kids have more than one disability, it’s a good idea to include all of them in the IEP. This can help get the right services and supports in place.

But the IEP will likely need to list a primary disability category. This is mainly for data-tracking reasons and will not limit the amount or type of services a child receives.

Variations in some states

Depending on where you live, your state may have more than 13 disability categories. For example, some states may split hearing impairment and deafness into two categories.

In most states, a child’s disability category is listed in their IEP. Iowa is the only state that doesn’t do this. (But it still keeps track of disability categories and reports this data to the federal government.)

To learn more about the categories in your state, contact a Parent Training and Information Center . They’re free and there’s at least one in every state.

Podcast: “IEPs: The 13 disability categories”

Listen to a 13-minute episode of “Understood Explains: IEPs.” Special educator Juliana Urtubey explains what you need to know about the 13 disability categories in IDEA.

Explore related topics

Understanding ieps.

The difference between IEPs and 504 plans

Download: Anatomy of an IEP

- Student Disability Services Homewood

- Available Assistive Technology

- Accommodation Descriptions

Examples of Disabilities

- Documentation Guidelines

- Student Rights & Responsibilities

- Requesting Housing Accommodations

- Grievance Procedures

- Voter Registration

- Career Resources

- Information Guides

- Providing Accommodations in the Classroom

- Faculty Rights & Responsibilities

- Frequently Asked Questions

- Meet the Staff

- Disability Coordinator List

- SDS Application Form (New Students and First-Time Requests)

Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder

Terminology.

ADHD are neurological conditions affecting both learning and behavior. They result from chronic disturbances in the areas of the brain that regulate attention, impulse control, and the executive functions, which control cognitive tasks, motor activity, and social interactions. Hyperactivity may or may not be present. Treatable, but not curable, ADHD affects three to six percent of the population.

Characteristics (may include)

- Inability to stay on task

- Easily distracted

- Poor time management skills

- Difficulty in preparing class assignments, keeping appointments, and attending class on time.

- Reading comprehension difficulties

- Difficulty with math problems requiring changes in action, operation and order

- Inability to listen selectively during lectures, resulting in problems with note taking

- Lack of organization in work, especially written work and essay questions

- Difficulty following directions, listening and concentrating

- Blurting out answers

- Poor handwriting

Considerations and Instructional Strategies

- Since these students often also have learning disabilities, effective accommodations may include those also used with students with learning disabilities.

- Effective instructional strategies include providing opportunities for students to learn using visual, auditory and hands-on approaches.

Blindness/Low Vision

The following terms are used in an educational context to describe students with visual disabilities:

- “Totally blind” students learn via Braille or other nonvisual media.

- “Legally blind” indicates that a student has less than 20/200 vision in the more functional eye or a very limited field of vision (20 degrees at its widest point).

- “Low vision” refers to a severe vision loss in distance and near vision. Students use a combination of vision and other senses to learn, and they may require adaptations in lighting or the print size, and, in some cases, Braille.

- If needed, introduce yourself at the beginning of a conversation and notify the student when you are exiting the room.

- Nonverbal cues depend on good visual acuity. Verbally acknowledging key points in the conversation facilitates the communication process.

- A student may use a guide dog or white cane for mobility assistance. A guide dog is a working animal and should not be petted.

- When giving directions, be clear: say “left” or “right,” “step up,” or “step down.” Let the student know where obstacles are; for example, “the chair is to your left” or “the stairs start in about three steps.”

- When guiding or walking with a student, verbally offer your elbow instead of grabbing his or hers.

- Allow the student to determine the most ideal seating location so he or she can see, hear and, if possible, touch as much of the presented material as possible.

- Discuss special needs for field trips or other out-of-class activities well in advance.

- Assist the student in labeling lab materials so that they are easily identifiable.

- Familiarize the student with the layout of the classroom or laboratory, noting the closest exits, and locating emergency equipment.

- Ask the student if he or she will need assistance during an emergency evacuation and assist in making a plan if necessary.

Brain Injuries

Brain injury may occur in many ways. Traumatic brain injury typically results from accidents; however, insufficient oxygen, stroke, poisoning, or infection may also cause brain injury. Brain injury is one of the fastest growing types of disabilities, especially in the age range of 15 to 28 years.

Characteristics

Highly individual; brain injuries can affect students very differently. Depending on the area(s) of the brain affected by the injury, a student may demonstrate difficulties with:

- Organizing thoughts, cause-effect relationships, and problem-solving

- Processing information and word retrieval

- Generalizing and integrating skills

- Social interactions

- Short-term memory

- Balance or coordination

- Communication and speech

- Brain injury can cause physical, cognitive, behavioral, and/or personality changes that affect the student in the short term or permanently.

- Recovery may be inconsistent. A student might take one step forward, two back, do nothing for a while and then unexpectedly make a series of gains.

- Effective teaching strategies include providing opportunities for a student to learn using visual, auditory and hands-on approaches.

- Ask the student if he or she will need assistance during an emergency evacuation and assist in making arrangements if necessary.

Deaf/Hard of Hearing

Students who are d/Deaf or hard of hearing require different accommodations depending on several factors, including the degree of hearing loss, the age of onset, and the type of language or communication system they use. They may use a variety of communication methods, including lip reading, cued speech, signed English and/or American Sign Language.

Deaf or hard of hearing students may:

- be skilled lip readers, but many are not; only 30 to 40 percent of spoken English is distinguishable on the mouth and lips under the best of conditions

- also have difficulties with speech, reading and writing skills, given the close relationship between language development and hearing

- use speech, lip reading, hearing aids and/or amplification systems to enhance oral communication

- be members of a distinct linguistic and cultural group; as a cultural group, they may have their own values, social norms and traditions

- use American Sign Language as their first language, with English as their second language

- American Sign Language (ASL) is not equivalent to English; it is a visual-spatial language having its own syntax and grammatical structure.

- Look directly at the student during a conversation, even when an interpreter is present, and speak in natural tones.

- Make sure you have the student’s attention before speaking. A light touch on the shoulder, wave or other visual signal will help.

- Recognize the processing time the interpreter takes to translate a message from its original language into another language; the student may need more time to receive information, ask questions and/or offer comments.

Communicating with Students who are d/Deaf

Students who are d/Deaf communicate in different ways depending on several factors: amount of residual hearing, type of deafness, language skills, age at onset of deafness, speech abilities, speech reading skills, personality, intelligence, family environment and educational background. Some are more easily understood than others. Some use speech only or a combination of sign language, finger spelling, and speech, writing, body language and facial expression. Students who are deaf use many ways to convey an idea to other people. The key is to find out which combination of techniques works best with each student. The important thing is not how you exchange ideas or feelings, but that you communicate.

To communicate with a person who is d/Deaf in a one-to-one situation

- Get the student’s attention before speaking. A tap on the shoulder, a wave, or another visual signal usually works. Clue the student into the topic of discussion. It is helpful to know the subject matter being discussed in order to pick up words and follow the conversation. This is especially important for students who depend on oral communication.

- Speak slowly and clearly. Do not yell, exaggerate, or over enunciate. It is estimated that only three out of 10 spoken words are visible on the lips. Overemphasis of words distorts lip movements and makes speech reading more difficult. Try to enunciate each word without force or tension. Short sentences are easier to understand than long ones. Look directly at the student when speaking. Even a slight turn of your head can obscure the speech reading view. Do not place anything in your mouth when speaking. Mustaches that obscure the lips and putting your hands in front of your face can make lip reading difficult.

- Maintain eye contact. Eye contact conveys the feeling of direct communication. Even if an interpreter is present, speak directly to the student. He or she will turn to the interpreter as needed. Avoid standing in front of a light source, such as a window or bright light. The bright background and shadows created on the face make it almost impossible to speech read.

- First repeat, and then try to rephrase a thought rather than repeating the same words. If the student only missed one or two words the first time, one repetition will usually help. Particular combinations of lip movements sometimes are difficult to speech read. If necessary, communicate by paper and pencil or by typing to each other on the computer email or fax. Getting the message across is more important than the method used. Use pantomime, body language, and facial expression to help communicate.

- Be courteous during conversation. If the phone rings or someone knocks at the door, excuse yourself and tell him or her that you are answering the phone or responding to the knock. Don’t ignore the student and talk with someone else while he or she waits.

- Use open-ended questions, which must be answered by more than “yes”, or “no.” Do not assume that the message was understood if the student nods his or her head. Open-ended questions ensure that your information has been communicated.

Participating in group situations with people who are d/Deaf

- Seat the student to his or her best advantage. This usually means a seat opposite the speaker, so that he or she can see the person’s lips and body language. The interpreter should be next to the speaker, and both should be illuminated clearly. Be aware of the room lighting.

- Provide new vocabulary in advance. It is difficult, if not impossible, to speech read or read finger spelling of unfamiliar vocabulary. If new vocabulary cannot be presented in advance, write the terms on paper, a blackboard, or an overhead projector. If a lecture or film will be presented, a brief outline or script given to the student and interpreter in advance helps them in following the presentation.

- Avoid unnecessary pacing and speaking when writing on a blackboard. It is difficult to speech read a person in motion and impossible to speech read one whose back is turned. Write or draw on the blackboard, then face the group and explain the work. If you use an overhead projector, don’t look down at it while speaking. Make sure the student does not miss vital information. Provide in writing any changes in meeting times, special assignments, or additional instructions. Allow extra time when referring to manuals or texts since the student who is deaf must look at what has been written and then return attention to the speaker or interpreter.

- Slow down the pace of communication slightly to facilitate understanding. Allow extra time for the student to ask or answer questions. Repeat questions or statements made from the back of the room. Remember that students who are deaf are cut off from whatever happens outside their visual area. Use hands-on experience whenever possible in training situations. Students who are deaf often learn quickly by doing. A concept, which may be difficult to communicate verbally, may be explained more easily by a hands-on demonstration.

- Use of an interpreter in large, group settings makes communication much easier. The interpreter will be a few words behind the speaker in transferring information; therefore, allow time for the student to obtain all the information and ask questions.

Using an Interpreter

- Speak clearly and in a normal tone, facing the person using the interpreter (do not face the interpreter).

- Do not rush through a lecture or presentation. The interpreter or the deaf student may ask the speaker to slow down or repeat a word or sentence for clarification. Allow time to study handouts, charts or overheads. A deaf student cannot watch the interpreter and study written information at the same time.

- Permit only one person at a time to speak during group discussions. It is difficult for an interpreter to follow several people speaking at once. Since the interpreter needs to be a few words behind the conversation, give the interpreter time to finish before the next person begins so the deaf student can join in or contribute to the discussion.

- If a class session is more than an hour and a half, two interpreters will usually be scheduled and work on a rotating basis. It is difficult to interpret for more than an hour and a half, and following an interpreter for a long time is tiring for a deaf student. Schedule breaks during lengthy classes so both may have a rest.

- Provide good lighting for the interpreter. If the interpreting situation requires darkening the room to view slides, videotapes, or films, auxiliary lighting is necessary so that the deaf student can see the interpreter. If a small lamp or spotlight cannot be obtained, check to see if lights can be dimmed, but still provides enough light to see the interpreter. If you are planning to present any video taped materials in your classroom, please order tapes that are closed captioned. Please request equipment that will display closed captioning, or request a VCR with a closed captioning decoder from Information Technology.

- You may ask the student to arrange for an interpreter for meetings during office hours. Often your classroom interpreter can schedule this time with you. For field trips and other required activities outside of regularly scheduled class time, the student must make a written request to the DS office as soon as possible, but at least two weeks before the event.

- Some courses require frequent use of a textbook during class time. Providing a desk copy to the interpreter for the semester will often facilitate communication. For technical courses, it can allow interpreters time to prepare signs for new vocabulary before interpreting the lecture.

- Bound by a professional code of ethics, interpreters are hired by the University to interpret what occurs in the classroom; interpreters are not permitted to join into conversations, voice personal opinions, or serve as general classroom aides. Do not make comments to interpreters that are not intended to be interpreted to the deaf student.

Adapted from: Communicating with a Student who is Deaf, Seattle Community College; Regional Education Center for Deaf Students.

An Online Orientation to serving students who are deaf or hard of hearing is available through the Postsecondary Education Programs Network website . The training takes about one hour and upon completion, participants may download and print a certificate issued by PEPNet.

Learning Disabilities

Learning disabilities are neurologically-based and may interfere with the acquisition and use of listening, speaking, reading, writing, reasoning, or mathematical skills. They affect the manner in which individuals with average or above-average intellectual abilities process and/or express information. A learning disability may be characterized by a marked discrepancy between intellectual potential and academic achievement resulting from difficulties with processing information. The effects may change depending upon the learning demands and environments and may manifest in a single academic area or impact performance across a variety of subject areas and disciplines.

Difficulties may be seen in one or more of the following areas:

- oral and/or written expression

- reading comprehension and basic reading skills

- problem-solving

- ability to listen selectively during lectures, resulting in problems with note-taking

- mathematical calculation and reasoning

- interpreting social cues

- time management

- organization of tasks, such as in written work and/or essay questions

- following directions and concentrating

- short-term memory

Instructors who use a variety of instructional modes will enhance learning for students with learning disabilities. A multi-sensory approach to teaching will increase the ability of students with different functioning learning channels—auditory, visual and/or haptic (hands-on)—to benefit from instruction.

Medical Disabilities

Other disabilities include conditions affecting one or more of the body’s systems. These include respiratory, immunological, neurological, and circulatory systems.

- Chronic Fatigue Syndrome

- Epilepsy/Seizure Disorder

- Fibromyalgia

- Lupus Erythematosus

- Multiple Sclerosis

- Chemical Dependency

- Epstein Barr virus

- Multiple Chemical Sensitivity

- Renal Disease

- The condition of a student with a medical disability may fluctuate or deteriorate over time, causing the need for and type of accommodation to vary.

- Fatigue may be a significant factor in the student’s ability to complete required tasks within regular time limits.

- Some of these conditions will cause the student to exceed an attendance policy. A reasonable accommodation should reflect the nature of the class requirements and the arrangements initiated by the student for completing the assignments. If you need assistance or guidance in determining a reasonable standard of accommodation, consult with a DS coordinator.

- A student may need to leave the classroom early and unexpectedly; the student should be held accountable for missed instruction.

Physical Disabilities

A variety of physical disabilities result from congenital conditions, accidents, or progressive neuromuscular diseases. These disabilities may include conditions such as spinal cord injury (paraplegia or quadriplegia), cerebral palsy, spina bifida, amputation, muscular dystrophy, cardiac conditions, cystic fibrosis, paralysis, polio/post-polio, and stroke.

Are highly individual; the same diagnosis can affect students very differently.

- When talking with a person who uses a wheelchair, try to converse at eye level; sit down if a chair is available.

- Make sure the classroom layout is accessible and free from obstructions.

- If a course is taught in a laboratory setting, provide an accessible workstation. Consult with the student for specific requirements, then with DS if additional assistance or equipment is needed.

- If a student also has a communication disability, take time to understand the person. Repeat what you understand, and when you don’t understand, say so.

- Ask before giving assistance, and wait for a response. Listen to any instructions the student may give; the student knows the safest and most efficient way to accomplish the task at hand.

- Let the student set the pace when walking or talking.

- A wheelchair is part of a student’s personal space; do not lean on, touch, or push the chair, unless asked.

- When field trips are a part of course requirements, make sure accessible transportation is available.

- Ask the student if he or she will need assistance during an emergency evacuation, and assist in making a plan if necessary.

Psychiatric Disabilities

Psychiatric disabilities refer to a wide range of behavioral and/or psychological problems characterized by anxiety, mood swings, depression, and/or a compromised assessment of reality. These behaviors persist over time; they are not in response to a particular event. Although many individuals with psychiatric disabilities are stabilized using medications and/or psychotherapy, their behavior and effect may still cycle.

- Students with psychiatric disabilities may not be comfortable disclosing the specifics of their disability.

- If a student does disclose, be willing to discuss how the disability affects him or her academically and what accommodations would be helpful.

- With treatment and support, many students with psychiatric disabilities are able to manage their mental health and benefit from college classes.

- If students seem to need counseling for disability-related issues, encourage them to discuss their problems with a Disability Coordinator.

- Sometimes students may need to check their perceptions of a situation or information you have presented in class to be sure they are on the right track.

- Sequential memory tasks, such as spelling, math, and step-by-step instructions may be more easily understood by breaking up the tasks into smaller ones.

- Drowsiness, fatigue, memory loss, and decreased response time may result from prescription medications.

Speech and Language Disabilities

Speech and language disabilities may result from hearing loss, cerebral palsy, learning disabilities, and/or physical conditions. There may be a range of difficulties from problems with articulation or voice strength to complete absence of voice. Included are difficulties in projection, fluency problems, such as stuttering and stammering, and in articulating particular words or terms.

- Give students opportunity—but do not compel speaking in class. Ask students for a cue they can use if they wish to speak.

- Permit students time to speak without unsolicited aid in filling in the gaps in their speech;

- Do not be reluctant to ask students to repeat a statement.

- Address students naturally. Do not assume that they cannot hear or comprehend.

- Patience is the most effective strategy in teaching students with speech disabilities.

Looking for something else?

Resource finder.

- Find Resources:

- I’d like to know what life is like as a JHU student

- What should I do next?

- I’m a first-year student

- I’m a second-year student

- I’m an upperclassman

- I’m a graduate student

- My child is thinking of going to JHU

- My child is a JHU student

- Choosing majors and courses

- Covering the costs of school

- Living a balanced lifestyle

- Getting real-world experience

- Doing something fun

- Campus and city living

- Becoming more involved

- Search Resources

- Vice Provost for Student Affairs

- Dean of Students

- Undergraduate

- School of Advanced International Studies

- Bloomberg School of Public Health

- Carey Business School

- School of Education

- School of Medicine

- School of Nursing

- Peabody Conservatory

- Events Calendar

- Promote an Event

- Report a Website Issue

- University Policies

- Title IX Information & Resources

- Higher Education Act Disclosures

- Accessibility

© Johns Hopkins University Baltimore, Maryland 410-516-8000 All rights reserved

- Go to font resize

- Go to main content

- Go to main menu

Moving Your Numbers

- A - Make text larger

- A - Reset text size to default

- A - Make text smaller

Download MYN Resources >

- You are here:

- Our Purpose >

Who are Students with Disabilities?

- Assumptions & Parameters

- Who are English Language Learners?

- District Nomination & Selection

- Bartholomew Consolidated School District, IN

- Bloom Vernon Local Schools, OH

- Brevard Public Schools, FL

- Gwinnett County Public Schools, GA

- Lake Villa School District #41, IL

- SAU 56, Somersworth, NH

- Stoughton Area School District, WI

- Tigard-Tualatin School District, OR

- Val Verde Unified School District, CA

- Wooster City Schools, OH

- Use Data Well

- Focus Your Goals

- Select & Implement Shared Instructional Practices

- Implement Deeply

- Monitor & Provide Feedback & Support

- Inquire & Learn

- Key Practices Guide

- State Education Agencies

- Districts & Their Schools

- Parents/Families

- Higher Education

- MYN Downloadable Resources

- District Downloadable Resources

- NCEO’s Core Work

- Partnerships

- Feature Stories

- Key Practices

- What Matters Most

- Tools & Resources

Have a success story to share? We'd love to feature it! Click here >

Special Education Students¹

Special education students are a diverse group of students nationally and within states, districts, and schools. The descriptions of special education students presented here come with several cautions.

It is inappropriate to assume that the labels of "special education" or groups within special education describe the characteristics of individual students. It is important to look beyond the group name (special education students) to develop appropriate mechanisms to accurately understand the characteristics of these students in greater detail.

It should be recognized that almost all special education students receive the majority of their instruction in the general education classroom and are participants in regular statewide assessments.

Special education students comprise 13% of the population of all public school students. Individual states vary in their percentages of special education students.2 Figure 1 shows the percentages of students receiving special education services in the 50 states and the District of Columbia in 2008-09.

Data were adapted from National Center for Education Statistics, Common Core of Data (CCD), "State Non-fiscal Survey of Public Elementary/Secondary Education," 2008-09 representing children ages 3-21 via http://nces.ed.gov » Data from Vermont were not included in the CCD data set. The information on state membership in this figure was accurate as of June, 2011.

Across the states, the population of public school students in special education ranged from less than 10% to 19%. One way to describe the characteristics of special education students is by their disability category, even though students within a single category have diverse needs. Most of the 6.5 million special education students (except for a portion with the most significant cognitive disabilities who may fall in such categories as intellectual disabilities, autism, and multiple disabilities) participate in the general state assessment. They do not participate in an alternate assessment based on alternate achievement standards.

Nationally, there are 13 special education disability categories. Figure 2 shows these categories, along with their prevalence nationally.

Data were adapted from Table 1-3 (Students ages 6 through 21 served under IDEA, Part B, by disability category and state: Fall 2008) via www.IDEAdata.org » for the 50 states.

* Developmental delay is applicable to children ages 3 through 9.

The percentages of students in each category vary tremendously across states. For example, the percentages of special education students with specific learning disabilities (LD) varied from 15% of the special education population in one state to 60% in another. The percentage of students with intellectual disabilities varied from 3% to 19%. Other categories of disability also show considerable variation.

Special education students receive their instruction in the general education setting for varying amounts of their instructional time.

Figure 3 shows the percentage of special education students who spend more than 80% of this time in the general education classroom. In most states, more that 50% of special education students spend more than 80% of their instructional time in general education classrooms.

Data were adapted from Table 2-2 (Students ages 6 through 21 served under IDEA, Part B, by disability category and state: Fall 2008) via www.IDEAdata.org » for the 50 states and DC. Data from Vermont was not available within this data set. ¹ This information was taken from Understanding Subgroups in Common State Assessments: Special Education Students and (ELLs) English Language Learners (NCEO, 2011). ² This and other general percentages are based on children ages 3-21. This age range is the most common one for which data are available across data sets used to describe students with disabilities and (ELLs) English Language Learners .

Our Partners

Council of Chief State School Officers (CCSSO) National Association of State Directors of Special Education (NASDSE) Supported by: U.S. Office of Special Education Programs

NCEO is supported primarily through Cooperative Agreements (#H326G050007, #H326G11002) with the Research to Practice Division, Office of Special Education Programs, U.S. Department of Education. Additional support for targeted projects, including those on ELL students, is provided by other federal and state agencies. The Center is affiliated with the Institute on Community Integration in the College of Education and Human Development , University of Minnesota . Opinions expressed in this publication do not necessarily reflect those of the U.S. Department of Education or Offices within it.

Special Education Guide

Disability Profiles

Under the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA), there are 13 categories under which a student is eligible to receive the protections and services promised by this law. In our disability profiles, we define each disability as specified by IDEA and explain it in plain English; these profiles also outline the common traits and educational challenges associated with each disability, and provide tips for parents and teachers.

- Deaf-Blindness

- Emotional Disturbance

- Hearing Impairment

- Intellectual Disability *

- Multiple Disabilities

- Orthopedic Impairment

- Other Health Impairments

- Specific Learning Disability

- Speech or Language Impairment

- Traumatic Brain Injury

- Visual Impairment

*Intellectual disability has also been referred to as “Mental Retardation” (MR) in the past, and this term and its acronym may be used colloquially or in older documentation. It is not, however, a currently accepted practice to refer to individuals with intellectual disabilities as “mentally retarded.”

Who is in special education and who has access to related services? New evidence from the National Survey of Children’s Health

Subscribe to the center for economic security and opportunity newsletter, nora gordon nora gordon professor - mccourt school of public policy, georgetown university, former brookings expert @noraegordon.

April 5, 2018

Executive Summary

This report brings data from the newly-released 2016 National Survey of Children’s Health (NSCH) to the robust policy and research debate over the extent to which differences in aggregate special education participation rates over racial and ethnic groups represent differences in underlying needs for special education.

The NSCH allows me to compare not only how student characteristics are related to participation in special education, but also how they relate to children’s access to speech therapy, occupational therapy, and physical therapy—services that may be delivered as part of a child’s special education plan. Like the existing literature, these analyses cannot control for a given child’s true need for special education or special therapies, but they can show how a range of demographic variables relate to access to both.

The unconditional means for special education participation as reported by parents in the NSCH are, as in other data sources, higher for blacks than whites, and lower for Hispanics and Asians than whites. Boys are more likely to participate than girls, and students who are eligible for free or reduced-price lunch are more likely to participate than their peers.

Once adjusting for free-lunch status and other basic demographics, black children in the NSCH participate in special education at a rate that is not statistically different from white children. Hispanic and Asian children, however, still participate at lower rates than whites with these adjustments. Overall, patterns in access to services roughly parallel patterns in special education participation.

The NSCH, unlike many education data sources, asks whether the child was born in the US. It reveals that children born outside of the United States are half as likely as their native-born peers to participate in special education. This pattern has received less policy attention than the race-based participation gap, and may point to issues with how schools identify students for special education.

introduction

In this report, I use the newly-released 2016 National Survey of Children’s Health (NSCH) to compare how student characteristics are related to participation in special education and access to speech therapy, occupational therapy, and physical therapy—services that may be delivered as part of a child’s special education plan. 1 While systematic relationships between demographics and participation in special education do not on their own reveal whether a particular group is over- or under-identified, they did prompt regulatory action from the Department of Education in the Obama Administration. These regulations are now on hold.

These data allow a descriptive lay of the land, rather than an investigation of how access to special education and to these services varies systematically with demographics conditional on actual need. They corroborate patterns from other data sources already in the public discourse around how race, ethnicity, and gender relate to special education. They also point to generally similar patterns in how these demographic factors relate to access to special therapies. Finally, they demonstrate the strikingly lower prevalence of special education participation—and access to services—for children born outside of the United States. Though existing literature has already pointed to lower probabilities of special education participation for students who are English learners, this disparity has received less attention in the public debate over identification.

As I have written about previously in this series , there is a sizeable literature focusing on these relationships. In particular, Paul Morgan, George Farkas, and collaborators have investigated the relationship between student characteristics and participation in special education with a variety of student-level data sources. 2 They consistently find that racial and ethnic minority students are underrepresented in special education, conditional on individual student characteristics. In related work, Morgan et al. have investigated the relationship between race and special education services for speech or language impairments and found similar patterns. The current analysis differs from their work by focusing on parental report of participation in special education, and access to special therapies including speech, occupational, or physical therapy, whether provided through school or not. The body of work by Morgan et al. consistently finds that English-language learners are less likely to be in special education; with the NSCH I examine nativity rather than language.

the national survey of children’s health as a special education data source

Studies of participation in special education typically rely on school district records, either used at the student-level through administrative data or aggregated and reported up to the federal level as required by Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA). The National Survey of Children’s Health, in contrast, is a phone-based survey; the analysis here uses the provided weights to correct for sampling bias due presence of a phone and non-response. Its purpose is to learn about children’s health care needs and access. The NSCH data on special education participation for school-aged children are derived from parent reports of whether the reference child in the survey currently has an Individualized Education Plan (IEP).

We would not expect rates of special education participation in the NSCH to match those reported by public schools under IDEA, which are tabulated by the National Center for Education Statistics (NCES).

First, the NCES rates are reported as a percentage of all children enrolled in public school , from pre-kindergarten through grade 12, while the NCSH rates are a percentage of all children (in this analysis, ages 5 through 17). The NSCH does not ask what kind of school children attend, so the denominator necessarily includes children who are homeschooled or enrolled in private school (and thus will not have IEPs), lowering the rate mechanically. Using national estimates of private and homeschooling rates, however, does not account for the full discrepancy between the two data sources.

Second, the NCES data come from district reports of children covered under IDEA, while the NSCH data come from parent reports. Though parental involvement is meant to be central in the development of a child’s IEP under IDEA, some parents may not know their child has an IEP, may not recognize the term, or may not wish to disclose this information on the survey. (The NSCH question asked about an Individualized Educational Plan, not about special education.) These channels would also lead to lower rates in the NSCH than in the NCES data.

Overall, I find that an IEP (or early intervention services) rate of 9.3 percent for children age 3-17 in the NSCH, compared with the NCES public school IEP rate of 13.0 percent reported for ages 3-21 in the 2014-15 school-year.

comparing special education rate by race and ethnicity across nces and nsch data

Figure 1 compares special education rates for major racial/ethnic groups across the NSCH and NCES data. Consistent with the mechanisms above, rates are indeed higher in the NCES data than the NSCH. The average rates in the NSCH are for 9.7 percent for white children, 12.4 percent for black children, 7.9 percent for Hispanic children, and 3.2 percent for Asian or Asian-American children.

As I discussed in my earlier post in this series, we do not know what the “correct” rate of participation for different groups would be. While the NSCH contains data on parental perceptions of the child, no data in the NSCH would allow me to estimate special education participation conditional on need. A difference in mean participation rates across groups could reflect over-identification of students in one group, under-identification of students in another, or “just right” identification across groups.

how do student and family characteristics mediate the relationship between race and special education?

Next I explore how a set of demographic variables mediate the relationship between a child’s race and ethnicity and the likelihood that he or she has an IEP.

Figure 2 shows results from estimating a linear probability model predicting the probability that a child in the school-aged (5-17) subpopulation of the NSCH currently has an IEP. Each bar represents the magnitude of the coefficient on the dichotomous race/ethnicity variable. For all regressions, the comparison (excluded) group is white students. All regressions also include indicator variables for Pacific Islanders, American Indian/Alaskan Natives, children whose parents report they are in two or more racial groups, and those whose parents report “other” race.

The first bar for each group shows the coefficient value for a regression with no other control variables. These coefficients differ from the mean special education rates in Figure 1 because they refer to differences from the mean for whites, the excluded group in the regressions. Without controlling for other variables, black students are 2.6 percentage points more likely to be in special education than whites, though the difference is not statistically significant. Hispanics are 1.7 percentage points less likely to be in special education than whites, while Asian and Asian-Americans are 6.3 percentage points less so; these differences are both statistically significantly different from zero.

Next, I adjust these coefficients (in the second bar for each group) for additional variables. These include a relatively standard set of student and family demographics: an indicator for whether anyone in the family received free or reduced-price meals at school in the past year, the family’s income as a percentage of the federal poverty line, whether the child was born in the United States, whether the child lives with a single mother, and the highest level of education either parent has attained. The NSCH also contains a set of questions about the child’s experience. I control for a series of variables indicating the child’s exposure to parental divorce, death, incarceration, if the child has ever witnessed or been a victim of violence, if the child has lived with someone with mental illness, and if the child has lived with someone with alcohol or other drug problems.

Adding these covariates affects the strength of the correlations differently for different groups. For black children, the relationship between race and special education remains positive but gets smaller in magnitude and becomes statistically insignificant. This is consistent with findings from Hibel, Farkas, and Morgan (2010). They then control for student-level kindergarten test scores and teacher ratings of student behavior; with those controls, they find black students are statistically significantly less likely to be in special education than whites. 3 The NSCH does not report test scores, so I cannot show how the results here would respond to their inclusion.

Asian and Asian-American children remain statistically significantly much less likely (by 4.8 percentage points) to participate in special education than their white peers, even after the additional controls are added. In other words, they are about half as likely to be in special education as whites, whose special education rate in the sample is 9.7 percent. And the negative relationship between Hispanic ethnicity and special education becomes stronger with the additional covariates.

special education versus access to specific services

People worry over different rates of special education participation across groups of students in part because they think it is likely to reflect inappropriate assignment of students to educational environment (this is especially true if they believe the true prevalence of need for special education is uniform across groups, before or after the types of demographic adjustments described above). But part of the concern comes from a belief that special education does not serve children well more generally. While the goal of special education is to provide supportive services and adaptations to allow all students to access the curriculum, many view it as a way of warehousing children who may be viewed as difficult in the general education classroom—whether or not they have disabilities that would qualify them for special education.

The NSCH allows us to break apart participation in special education from access to a set of services commonly found in IEPs. It asks parents whether their children have received any occupational, physical, or speech therapy in the past year. In practice, children may receive these services outside of a school setting, or within it; those receiving services at school are likely to receive them through an IEP or 504 plan. The NSCH does not ask parents where their children received these services, so we have no way to know if these services were received at school or elsewhere, or if they were delivered as part of an IEP. To be clear, these services are not included in all IEPs, nor do all children receiving these services need an IEP.

Figure 3 shows the same coefficients from the race/ethnicity variables, with covariates included, when predicting participation in special education (these were in the second bar for each group in Figure 2 and now are in the first bar for each group in Figure 3).

In Figure 4, I show the coefficients on those variables, aside from race and ethnicity, that are statistically significantly different from zero. (All other coefficients for control variables listed earlier are not only statistically insignificant, but also close to zero.) As in Figure 3, the first bar is for coefficients predicting special education participation, and the second bar is for predicting receipt of these specific therapeutic services. As with the race and ethnicity variables, the relationship between each of these characteristics and access to services is not statistically significant different from its relationship with special education.

As has been documented extensively, boys are much more likely—here, 6 percentage points—to participate in special education, and 5 percentage points more likely to receive these services. Compared to the average rates for girls, this is close to twice as likely for both outcomes.

The free or reduced-price meals indicator is associated with a 4.3 percentage point (56 percent) increase in the probability that a child currently has an IEP, and a 3.2 percentage point increase in access to services (57 percent). Once this control is in place, the family income variable (not shown) has no additional explanatory power over either outcome.

Being born in the United States is associated with being 3.6 percentage points, or 82 percent, more likely to participate in special education. In contrast, it is associated with being 1.9 percentage points, or 41 percent, more likely to access services.

Finally, children who have ever lived with someone with mental illness participate in special education at a statistically significant higher rate—by 3.3 percentage points—than those who have not; they are 6.5 percentage points more likely to access services. This is nearly twice as likely to use services as their counterparts.

Family structure and parental education, not shown, have no predictive power in this sample once the above covariates are included.

implications

The scope and scale of the NSCH permit a unique glimpse into who gets what services and placements, but not whether these patterns are appropriate. It is not designed to test whether students receive appropriate placement into special versus general education—indeed, no parent survey could be. And while the survey asks parents if children needed the services examined (speech, occupational, or physical therapy) I did not analyze the use of service conditional on stated need but rather simply whether they accessed the services at all. For such specialized services, many parents will not know if their children need services unless they are referred so we would not want to interpret parental report of no need in a clinical sense.

Policymakers, practitioners, and advocates wish to understand patterns of placement into special education and what they may reveal about flaws in how students with disabilities are identified and served in public schools. The patterns in the NSCH data are consistent with existing discussions around race and gender—in particular, higher prevalence for males and blacks. The NSCH data also reveal the lower rate of special education participation for students born outside the United States.

The author did not receive any financial support from any firm or person for this article or from any firm or person with a financial or political interest in this article. She is currently not an officer, director, or board member of any organization with an interest in this article.

Related Content

Nora Gordon

September 20, 2017

Elizabeth Setren, Nora Gordon

April 20, 2017

Thomas Hehir

December 14, 2016

Related Books

Brahima Sangafowa Coulibaly, Zia Qureshi

August 1, 2024

R. David Edelman

May 7, 2024

Nicol Turner Lee

August 6, 2024

- Child and Adolescent Health Measurement Initiative. National Survey of Children’s Health 2016 Enhanced Data File. Data Resource Center for Child and Adolescent Health.

- For their most recent work synthesizing the literature, see Morgan, Farkas et al. (2018). http://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1177/0014402917748303

- In Hibel, Farkas and Morgan (2010), the “underrepresentation” of blacks in special education becomes statistically significant only once the test score controls are included, going from Model 2 to Model 3 in Table 5. http://journals.sagepub.com/doi/pdf/10.1177/0014402917718341

Early Childhood Education Education Access & Equity K-12 Education

Economic Studies

Center for Economic Security and Opportunity

Sofoklis Goulas

June 27, 2024

Modupe (Mo) Olateju, Grace Cannon, Kelsey Rappe

June 14, 2024

Jon Valant, Nicolas Zerbino

June 13, 2024

- What is Special Education

- Special Ed Law

- Individuals with Disabilities Act (IDEA)

- Section 504

- IEP Process

- Disabilities

- Autism Spectrum Disorder

- Private School

- Home School

- School Success

- Special Ed FAQ

- Special Ed Terms

- Privacy Policy

What is Special Education?

After an IEP meeting, have you ever left your school wondering:

- What just happened? What did I sign?

- Is my child getting the best possible services?

- Am I asking the right questions? Does this plan really meet my child's needs?

WHAT IS SPECIAL EDUCATION?

Special education is a broad term used by public K-12 school districts and the law (IDEA) to describe specially designed instruction that meets the unique needs of a child who has been identified as having a specific learning disability. If a student is found to have one or more of the 13 qualifying conditions, any services deemed necessary are provided free of charge by the public school system. Learning disabilities cover a wide spectrum of disorders ranging from mild to severe and can include mental, physical, behavioral and emotional disabilities.

There are 13 categories of special education as defined by the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA). In order to qualify for special education, the IEP team must determine that a child has one or more of the following and it must adversely affect their educational performance.

- Emotional Disturbance

- Hearing Impairment

- Intellectual Disability

- Multiple Disabilities

- Orthopedic Impairment

- Other Health Impaired

- Specific Learning Disability

- Speech or Language Impairment

- Traumatic Brain Injury

- Visual Impairment

GOALS of SPECIAL EDUCATION

Special education makes it possible for your child to achieve academic success in the least restrictive environment despite their disability. The federal law overseeing special education is called the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act or IDEA. IDEA entitles all children to a free appropriate education (FAPE). Examples of "appropriate" programs include:

- A specific program or class for your child.

- Access to specialists.

- Modifications in the educational program such as curriculum and teaching methods.

There are hundreds of unfamiliar terms and acronyms in the IEP process. When you have time, I encourage you to review the terms and definitions appendix . One thing to remember is that APPROPRIATE does not mean BEST. Every child would benefit from receiving the best of everything. This is an important distinction to remember.

HOW DO I GET STARTED?

If your child is struggling in school, having social or behavioral problems, or if you suspect they have one of the 13 categories of special education, you can request an evaluation. Some school districts request that you meet with your school's student study team (SST) before conducting an evaluation. If your child does not qualify for services under IDEA, they may qualify for modifications under Section 504 of the American Disabilities Act of 1973.

If you child attends a private school, you should read my special section on PRIVATE SCHOOLS as special education law is only mandated to public K-12 institutions.

What is an SST? What is a 504 Plan?

Would you prefer to share this page with others by linking to it?

- Click on the HTML link code below.

- Copy and paste it, adding a note of your own, into your blog, a Web page, forums, a blog comment, your Facebook account, or anywhere that someone would find this page valuable.

- Learning Library

- Exceptional Teacher Resource Repository

- Create an Account

Ethical Principles and Practice Standards

Special Education Professional Ethical Principles

Download PDF

Professional special educators are guided by the Council for Exceptional Children (CEC) professional ethical principles, practice standards, and professional policies in ways that respect the diverse characteristics and needs of individuals with exceptionalities and their families. They are committed to upholding and advancing the following principles:

- Maintaining challenging expectations for individuals with exceptionalities to develop the highest possible learning outcomes and quality of life potential in ways that respect their dignity, culture, language, and background.

- Maintaining a high level of professional competence and integrity and exercising professional judgment to benefit individuals with exceptionalities and their families.

- Promoting meaningful and inclusive participation of individuals with exceptionalities in their schools and communities.

- Practicing collegially with others who are providing services to individuals with exceptionalities.

- Developing relationships with families based on mutual respect and actively involving families and individuals with exceptionalities in educational decision making.

- Using evidence, instructional data, research, and professional knowledge to inform practice.

- Protecting and supporting the physical and psychological safety of individuals with exceptionalities.

- Neither engaging in nor tolerating any practice that harms individuals with exceptionalities.

- Practicing within the professional ethics, standards, and policies of CEC; upholding laws, regulations, and policies that influence professional practice; and advocating improvements in the laws, regulations, and policies.

- Advocating for professional conditions and resources that will improve learning outcomes of individuals with exceptionalities.

- Engaging in the improvement of the profession through active participation in professional organizations.

- Participating in the growth and dissemination of professional knowledge and skills.

Translations

CEC Ethics in Arabic CEC Ethics in English CEC Ethics in Greek CEC Ethics in Korean CEC Ethics in Russian CEC Ethics in Spanish CEC Ethics in Traditional Chinese

Translations coordinated by Alice Farling on behalf of DISES.

Special Education Standards for Professional Practice

- Systematically individualize instructional variables to maximize the learning outcomes of individuals with exceptionalities.

- Identify and use evidence-based practices that are appropriate to their professional preparation and are most effective in meeting the individual needs of individuals with exceptionalities.

- Use periodic assessments to accurately measure the learning progress of individuals with exceptionalities, and individualize instruction variables in response to assessment results.

- Create safe, effective, and culturally responsive learning environments which contribute to fulfillment of needs, stimulation of learning, and realization of positive self-concepts.

- Participate in the selection and use of effective and culturally responsive instructional materials, equipment, supplies, and other resources appropriate to their professional roles.

- Use culturally and linguistically appropriate assessment procedures that accurately measure what is intended to be measured, and do not discriminate against individuals with exceptional or culturally diverse learning needs.

- Only use behavior change practices that are evidence-based, appropriate to their preparation, and which respect the culture, dignity, and basic human rights of individuals with exceptionalities.

- Support the use of positive behavior supports and conform to local policies relating to the application of disciplinary methods and behavior change procedures, except when the policies require their participation in corporal punishment.

- Refrain from using aversive techniques unless the target of the behavior change is vital, repeated trials of more positive and less restrictive methods have failed, and only after appropriate consultation with parents and appropriate agency officials.

- Do not engage in the corporal punishment of individuals with exceptionalities.

- Report instances of unprofessional or unethical practice to the appropriate supervisor.

- Recommend special education services necessary for an individual with an exceptional learning need to receive an appropriate education.

- Represent themselves in an accurate, ethical, and legal manner with regard to their own knowledge and expertise when seeking employment.

- Ensure that persons who practice or represent themselves as special education teachers, administrators, and providers of related services are qualified by professional credential.

- Practice within their professional knowledge and skills and seek appropriate external support and consultation whenever needed.

- Provide notice consistent with local education agency policies and contracts when intending to leave employment.

- Adhere to the contracts and terms of appointment, or provide the appropriate supervisor notice of professionally untenable conditions and intent to terminate such employment, if necessary.

- Advocate for appropriate and supportive teaching and learning conditions.

- Advocate for sufficient personnel resources so that unavailability of substitute teachers or support personnel, including paraeducators, does not result in the denial of special education services.

- Seek professional assistance in instances where personal problems interfere with job performance.

- Ensure that public statements made by professionals as individuals are not construed to represent official policy statements of an agency.

- Objectively document and report inadequacies in resources to their supervisors and/or administrators and suggest appropriate corrective action(s).

- Respond objectively and non-discriminatively when evaluating applicants for employment including grievance procedures.

- Resolve professional problems within the workplace using established procedures.

- Seek clear written communication of their duties and responsibilities, including those that are prescribed as conditions of employment.

- Expect that responsibilities will be communicated to and respected by colleagues, and work to ensure this understanding and respect.

- Promote educational quality and actively participate in the planning, policy development, management, and evaluation of special education programs and the general education program.

- Expect adequate supervision of and support for special education professionals and programs provided by qualified special education professionals.

- Expect clear lines of responsibility and accountability in the administration and supervision of special education professionals

- Maintain a personalized professional development plan designed to advance their knowledge and skills, including cultural competence, systematically in order to maintain a high level of competence.

- Maintain current knowledge of procedures, policies, and laws relevant to practice.

- Engage in the objective and systematic evaluation of themselves, colleagues, services, and programs for the purpose of continuous improvement of professional performance.

- Advocate that the employing agency provide adequate resources for effective school-wide professional development as well as individual professional development plans.

- Participate in systematic supervised field experiences for candidates in preparation programs.

- Participate as mentors to other special educators, as appropriate.

- Recognize and respect the skill and expertise of professional colleagues from other disciplines as well as from colleagues in their own disciplines.

- Strive to develop positive and respectful attitudes among professional colleagues and the public toward persons with exceptional learning needs.

- Collaborate with colleagues from other agencies to improve services and outcomes for individuals with exceptionalities.

- Collaborate with both general and special education professional colleagues as well as other personnel serving individuals with exceptionalities to improve outcomes for individuals with exceptionalities.

- Intervene professionally when a colleague’s behavior is illegal, unethical, or detrimental to individuals with exceptionalities.

- Do not engage in conflicts of interest.

- Assure that special education paraeducators have appropriate training for the tasks they are assigned.

- Assign only tasks for which paraeducators have been appropriately prepared.

- Provide ongoing information to paraeducators regarding their performance of assigned tasks.

- Provide timely, supportive, and collegial communications to paraeducators regarding tasks and expectations.

- Intervene professionally when a paraeducator’s behavior is illegal, unethical, or detrimental to individuals with exceptionalities.

- Use culturally appropriate communication with parents and families that is respectful and accurately understood.

- Actively seek and use the knowledge of parents and individuals with exceptionalities when planning, conducting, and evaluating special education services and empower them as partners in the educational process.

- Maintain communications among parents and professionals with appropriate respect for privacy, confidentiality, and cultural diversity.

- Promote opportunities for parent education using accurate, culturally appropriate information and professional methods.

- Inform parents of relevant educational rights and safeguards.

- Recognize and practice in ways that demonstrate respect for the cultural diversity within the school and community.

- Respect professional relationships with students and parents, neither seeking any personal advantage, nor engaging in inappropriate relationships.

- Do not knowingly use research in ways that mislead others.

- Actively support and engage in research intended to improve the learning outcomes of persons with exceptional learning needs.

- Protect the rights and welfare of participants in research.

- Interpret and publish research results with accuracy.

- Monitor unintended consequences of research projects involving individuals with exceptionalities, and discontinue activities which may cause harm in excess of approved levels.

- Advocate for sufficient resources to support long term research agendas to improve the practice of special education and the learning outcomes of individuals with exceptionalities.

- Maintain accurate student records and assure that appropriate confidentiality standards are in place and enforced.

- Follow appropriate procedural safeguards and assist the school in providing due process.

- Provide accurate student and program data to administrators, colleagues, and parents, based on efficient and objective record keeping practices.

- Maintain confidentiality of information except when information is released under specific conditions of written consent that meet confidentiality requirements.

- Engage in appropriate planning for the transition sequences of individuals with exceptionalities.

- Perform assigned specific non-educational support tasks, such as administering medication, only in accordance with local policies and when written instructions are on file, legal/policy information is provided, and the professional liability for assuming the task is disclosed.

- Advocate that special education professionals not be expected to accept non-educational support tasks routinely.

From becoming a member to assisting with your membership, groups, event registrations and book orders, we’re here to help.

- Customer Service Center

Unequal and Increasingly Unfair: How Federal Policy Creates Disparities in Special Education Funding

The formula used to allocate federal funding to states for special education is one of IDEA's most critical components. The formula serves as the primary mechanism for dividing available federal...

Adapted Physical Education: Meeting the Requirements of the Individuals With Disabilities Education Act

The Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA) requires that school districts provide eligible students with specially designed instruction that confers a free appropriate public education...

Big Ideas in Special Education: Specially Designed Instruction, High-Leverage Practices, Explicit Instruction, and Intensive Instruction

The mandate to provide specially designed instruction to support the learning and behavioral needs of students with disabilities is at the core of special education. As the field of special education...

© 2024 Council for Exceptional Children (CEC). All rights reserved.

- Privacy Policy & Terms of Use

- Accessibility Statement

- Partner Solutions Directory

Twice Exceptional: Definition, Characteristics & Identification

Twice-exceptional students (also known as 2e children or students) are among the most under-identified and underserved population in schools. The reason for this is two-fold: (1) the vast majority of school districts do not have procedures in place for identifying twice-exceptional students and (2) inadequate identification leads to the lack of access to appropriate educational services. Additionally, twice-exceptional students, whose gifts and disabilities often mask one another, are difficult to identify. Without appropriate educational programming, twice exceptional students and their talents go unrealized. In this article, we’ll be reviewing common characteristics of twice exceptional students, how these students can be identified and ways to support their development and growth.

What is twice exceptional (2e)?

The term “twice exceptional” or “2e” refers to intellectually gifted children who have one or more learning disabilities such as dyslexia, ADHD, or autism spectrum disorder. Twice-exceptional children think and process information differently. Like many other gifted children, 2e kids may be more emotionally and intellectually sensitive than children of average intelligence. At the same time, due to uneven development (asynchrony) or their learning differences, twice exceptional kids struggle with what other kids do easily. Because of their unique abilities and characteristics, 2e students need a special combination of education programs and counseling support.

What are the characteristics of twice exceptional children?

Twice exceptional kids may display strengths in certain areas and weaknesses in others. Common characteristics of twice exceptional students include:

- Outstanding critical thinking and problem-solving skills

- Above average sensitivity, causing them to react more intensely to sounds, tastes, smells, etc.

- Strong sense of curiosity

- Low self-esteem due to perfectionism

- Poor social skills

- Strong ability to concentrate deeply in areas of interest

- Difficulties with reading and writing due to cognitive processing deficits

- Behavioral problems due to underlying stress, boredom and lack of motivation

Check out this article from the Davidson Institute on twice-exceptional characteristics for more traits and characteristics.

How do you identify twice exceptional students?

Identification for twice exceptional students is often a complicated process and requires the unique ability to assess and identify the two areas of exceptionality. Sometimes the disability may be hidden, also known as “masking,” which can complicate the identification process. At the same time, most school districts have no procedures in place for identifying or meeting the academic needs of twice-exceptional children, leaving many 2e kids under-identified and underserved.

According to NAGC’s report on twice exceptionality , 2e kids may be identified in one of three categories:

- Go unnoticed for possible special education evaluation

- Be considered underachievers, often perceived as lazy or unmotivated

- Achieve at grade level until curriculum becomes more difficult, often during middle and high school

- Be a part of programs that focus solely on their disability

- Be inadequately assessed for their intellectual abilities

- Become bored in special programs if the services do not challenge them appropriately

- Be considered achieving at grade level and assumed to have average ability

- Struggle as curriculum becomes more challenging

- Never be referred for a special education evaluation due to deflated achievement and standardized test scores

Due to the difficulty of identifying twice-exceptional students and the lack of awareness in school districts, 2e kids may go undiagnosed for being either gifted, disabled or both. This can affect twice exceptional students in significant ways including a higher likelihood to drop out of school.

If you are a parent seeking identification, it is important to work with a professional who is knowledgeable about twice exceptionality and can provide recommendations on how to appropriately address both the child’s strengths and weaknesses. TECA (Twice Exceptional Children’s Advocacy) offers a searchable database of professionals who work with twice exceptional children and their families. This free resource can be used as a tool for researching practitioners.

Tips for identifying twice-exceptional students

Oftentimes, multiple classification in giftedness and disability can complicate proper identification and lead to a misdiagnosis. To help with this process, we have gathered some tips from experts in the 2e community, including SENG , 2e Newsletter and NAGC , on identifying twice-exceptional students:

- Take a multi-dimensional approach to identifying twice-exceptional students and consider using both written tests and behavioral assessments

- Use both formal and informal assessments

- Separate out test scores on IQ tests; most 2e children are inconsistent performers with uneven skills and asynchronous development

- Reduce qualifying cut off scores to account for learning differences or disabilities

- Consider oral questioning instead of formal written testing if the student experiences difficulties with processing details

- Extend the time available for the student to demonstrate their knowledge

- Use assessment procedures that accommodate language and cultural differences to avoid bias in the identification process

What percentage of students are twice exceptional?

The number of twice-exceptional students is unclear. However, we can come up with a reasonable estimate based on the number of kids in the U.S. who are gifted or have received special education services for their learning disability.