108 Gambling Essay Topic Ideas & Examples

🏆 best gambling topic ideas & essay examples, ⭐ good research topics about gambling, 👍 simple & easy gambling essay titles, ❓ research questions on gambling.

- Gambling Benefits and Disadvantages Also in relation to this, the gambling industry offers employment to a myriad of people. This is thus a boost to the economy of the local people.

- Online Gambling Addiction Gambling is an addiction as one becomes dependent on the activity; he cannot do without it, it becomes a necessity to him. Online gambling is more of an addiction than a game to the players.

- Gambling as an Acceptable Form of Leisure In leisure one should have the freedom to choose which activity to engage in and at what time to do it. Gambling is considered as a form of leisure activity and one has freedom to […]

- Online Gambling Legalization When asked about the unavoidable passing of a law decriminalizing online gambling in the US, the CEO of Sams Casino stated that the legislation would not have any impact on their trade.

- Impact of Gambling on the Bahamian Economy Sources from the government of The Bahamas indicate that the first of gambling casinos in the name of the Bahamian Club opened for business from the capital of Nassau towards the close of the 1920s […]

- Gambling’s Positive and Negative Effects In some cases such as in lotteries, the financial reward is incidental and secondary because the participants drive is to help raise funds for the course the lottery promotes.

- Comorbid Gambling Disorder and Alcohol Dependence The patient was alert and oriented to the event, time, and place and appropriately dressed for the occasion, season, and weather.

- Gambling: Debate Against the Legislation of Gambling More significantly, the Australian government has so far adopted a conciliatory and indulgent attitude towards most kinds of gambling, which has been the main reason for the rampant growth and proliferation of both forms of […]

- Impact of Internet Use, Online Gaming, and Gambling Among College Students The researchers refute the previous works of literature that have analyzed the significance of the Internet, whereby previous studies depict that the Internet plays a significant role in preventing depression ordeals and making people happy.

- History of Gambling in the US and How It Connects With the Current Times It is possible to note that it is in the Americans’ blood from the sides of Native Americans and the Pilgrims to bet.

- Effects of Gambling on Happiness: Research in the Nursing Homes The objective of the study was to determine whether the elderly in the nursing homes would prefer the introduction of gambling as a happiness stimulant.

- The Era of Legalized Gambling Importantly, they build on each other to demonstrate power in taking risk action and actually how legalizations of the practice can influence character integrity. The conclusive speculation is whether there is a changing definition of […]

- Legalization of Casino Gambling in Hong Kong Thus, the problem is in the controversy of the allegedly positive and negative effects of gambling legalization on the social and economic development of Hong Kong.

- Internet Gambling Issue Description There are certain new features added to the gambling game by the internet gamblers, such as proxy gambling, gambling for credit and claim of gambling in the virtual offshore gambling environment.

- The Problem of Gambling in the Modern Society as the Type of Addiction Old people and adolescents, rich and poor, all of them may become the prisoners of this addiction and the only way out may be the treatment, serious psychological treatment, as gambling addiction is the disease […]

- The Psychology of Lottery Gambling This kind of gambling also refers to the expenditure of more currency than was first future and then returning afterward to win the cash lost in the history.

- Gambling, Fraud and Security in Banking By supervising the institutions and banks, there exists openness into the dealings of the banks and this allows investors to get full information about the banks before investing.

- High-Risk Gambles Prevention in Banking The elements of a valid contract between banks and their customers vary according to the context of the contract. This involves the willingness and devotion of both parties to a particular cause.

- Earmark Gambling Revenue Legislation in Illinois The state of Illinois enacted PA 91-40 in 1999, which has affected the gaming industry. The growth in the revenue from gambling has attracted the attention of lawmakers.

- Jay Cohen’s Gambling Company and American Laws Disregarding the controversy concerning the harmful effects of gambling, one might want to ask the question concerning whether the USA had the right to question the policies of other states, even on such a dubious […]

- Internet Gambling and Its Impact on the Youth However, it is necessary to remember that apart from obvious issues with gambling, it is also associated with higher crime rates and it is inevitable that online gambling will fuel an increase of crime rates […]

- Fantasy Football: Gambling Regulation and Outlawing Taking this into consideration, it can be stated that fantasy football and its other iterations on sites like Draft Kings is not a form of gambling.

- Gambling and Addiction’s Effects on Neuroplasticity It was established further that blood flow from other parts of the body to the brain is changes whenever an individual engages in gambling, which is similar to the intake of cocaine.

- Gambling and Its Effect on Families The second notable effect of gambling on families is that it results in the increased cases of domestic violence. The third notable effect of gambling on the family is that it increases child abuse and […]

- Casino Gambling Legalization in Texas In spite of the fact that the idea of legalizing casino gambling is often discussed by opponents as the challenge to the community’s social health, Texas should approve the legalization of casino gambling because this […]

- Economic Issues: Casino Gambling Evidence from several surveys suggests that the competition from various states within the US has contributed to the growth and expansion of casinos. The growth and expansion of casinos has been fueled by competition from […]

- Casino Gambling Industry Trends This will make suppliers known to the rest of the companies operating in the industry. The bargaining power of the supplier in the casino gambling industry is also high.

- Gambling Addiction Research Approaches Therefore, it is possible to claim that the disease model is quite a comprehensive approach which covers several possible factors which lead to the development of the disorder.

- Public Policy on Youth Gambling The outcomes of the research would be useful in identifying the program outcomes as well as provide answers to the whys of youth gambling.

- Gambling and Gaming Industry Compulsive gambling Compulsive gambling refers to the inability to control an individual’s urge to engage in gambling activities. Other gambling activities in the state are classified as a misdemeanour.

- Revision of Problem Gambling The reasoning behind the researchers’ decision to focus on the social and financial factors of gambling within the UK is because of the significant increase in gambling-related problems within Britain.

- Positive Aspects of Gambling It is therefore essential for sociologist to understand the positive aspects of gambling and the impact that it has on our lives. However, it is essential to control the level of gambling.

- Argument for Legalization of Gambling in Texas The subject of gambling is that the gambler losses the money offered if the outcome of the event is against him or her or gains the money offered if the event outcome favors the gambler.

- Gambling in Kentucky: Moral Obligations vs. the Economical Reasons The industries that added to the well-being of the state and its GNP since the day the state was founded and throughout the past century was the coal mining, which contributed to the state’s income […]

- Gambling in Ohio The purpose of this project is to investigate the history of gambling in Ohio, its development in the 1990s, and its impact on ordinary human lives in order to underline the significance of this process […]

- Gambling Projects: Impact on the Cultural Transformations in America The high rates of unemployment and low earning levels may coerce residents to engage in gambling, hoping that they would enrich themselves.

- Gambling in Four Perspectives A gambler faces the challenge of imminent effect of addiction to the effects of gambling every time he continues with the exercise of gambling something that may take long to drop.

- Gambling Discusses Three Causes or Effects of Gambling and Their Impact on Society

- Taking the Risk: Love, Luck, and Gambling in Literature

- Financial Crime and Gambling in a Virtual World

- Management and Information Issues for Industries With Externalities: The Case of Casino Gambling

- Internet Gambling Consumers Industry and Regulation

- Human Resource Management for Gambling Industry

- Youth Gambling Abuse: Issues and Challenges to Counselling

- Differentiate Between Investment Speculation and Gambling

- The Gambling and Its Influence on the Individual and Society

- Assessing the Differential Impacts of Online, Mixed, and Offline Gambling

- Gambling Taxation: Public Equity in the Gambling Business

- Risk and Protective Factors in Problem Gambling: An Examination of Psychological Resilience

- Behavioral Accounts and Treatments of Problem Gambling

- Cognitive Remediation Interventions for Gambling Disorder

- Gambling: The Problems and History of Addiction, Helpfulness, and Tragedy

- Casino Gambling Myths and Facts: When Fun Becomes Dangerous

- Associations Between Problem Gambling, Socio-Demographics, Mental Health Factors, and Gambling Type

- Gambling With the House Money and Trying to Break Even: The Effects of Prior Outcomes on Risky Choice

- Differences in Effects on Brain Functional Connectivity in Patients With Internet-Based Gambling Disorder and Internet Gaming Disorder

- Gambling Addiction Hidden Evils of Online Play

- Diagnosing and Treating Pathological Addictions: Compulsive Gambling, Drugs, and Alcohol Addiction

- The Pleasure Principle: Gambling and Brain Chemistry

- Gambling, Geographical Variations, and Deprivation: Findings From the Adult Psychiatric Morbidity Survey

- Behavior Change Strategies for Problem Gambling: An Analysis of Online Posts

- Economic Recession Affects Gambling Participation but Not Problematic Gambling: Results From a Population-Based Follow-up Study

- Different Gambling Consequence Western Civilisation Countries Sociology

- Gambling Among Culturally Diverse Older Adults: A Systematic Review of Qualitative and Quantitative Data

- Decision-Making Under Risk, but Not Under Ambiguity, Predicts Pathological Gambling in Discrete Types of Abstinent Substance Users

- Gambling: The Game Where Everyone Is a Loser

- The Problems and Issues Concerning Legalization of Online Gambling

- Gambling Attitudes and Beliefs Associated With Problem Gambling: The Cohort Effect of Baby Boomers

- Pathological Compulsive Gambling: Diagnosis and Treatment of a Medical Disorder

- Accounting and Financial Reports in the Gambling Monopoly – Measures for a Moral Economic System

- Gender, Gambling Settings and Gambling Behaviors Among Undergraduate Poker Players

- Gambling Among Young Croatian People: An Exploratory Study of the Relationship Between Psychopathic Traits, Risk-Taking Tendencies, and Gambling-Related Problems

- Buying and Selling Price for Risky Lotteries and Expected Utility Theory With Gambling Wealth

- Charitable Giving and Charitable Gambling: Cognitive Abilities, Non-cognitive Skills, and Gambling Behaviors

- Compulsive Buying Behavior: Characteristics of Comorbidity With Gambling Disorder

- Motivation, Personality Type, and the Choice Between Skill and Luck Gambling Products

- Gambling and the Use of Credit: An Individual and Household Level Analysis

- Why Will Internet Gambling Prohibition Ultimately Fail?

- How Do Binge Drinking, Gambling, and Procrastinating Affect Students?

- What Motivates Gambling Behavior?

- Does Charitable Gamble Crowd Out Charitable Donations?

- What Should the State’s Policy Be On Gambling?

- How Does Gambling Effect the Economy?

- What Does the Bible Say About Gambling?

- Are There Gambling Effects in Incentive-Compatible Elicitations of Reservation Prices?

- How Does the Gambling Affect the Society?

- Does Indian Casino Gambling Reduce State Revenues?

- How Does the Stigma of Problem Gambling Influence Help-Seeking, Treatment, and Recovery?

- Why Are Gambling Markets Organised So Differently From Financial Markets?

- Can Expected Utility Theory Explain Gambling?

- What Is the Attraction to Gambling?

- Should Sports Gambling Be Legalized?

- Who Gets Hurt From Gambling?

- How Do Gambling Addiction Affect Families?

- Does Individual Gambling Behavior Vary Across Gambling Venues With Differing Numbers of Terminals?

- Why Gambling Should Not Be Prohibited or Policed?

- How Has Gambling Become the Favorite Distraction of Americans?

- Should Age Restriction for Gambling Be Increase?

- Are There Net State Social Benefits or Costs From Legalizing Slot Machine Gambling?

- What Are the Possible Circumstances for Gambling?

- How Do Habit and Satisfaction Affect Player Retention for Online Gambling?

- Does DRD2 Taq1A Mediate Aripiprazole-Induced Gambling Disorder?

- How Does the Online Gambling Ban Help Al Qaeda?

- Does Pareto Rule Internet Gambling?

- Should Governments Sponsor Gambling?

- What Are the Problems Associated With Gambling?

- Why Isn’t Congress Closing a Loophole That Fosters Gambling in College?

- Economic Topics

- Hobby Research Ideas

- Ethics Ideas

- Online Community Essay Topics

- Mobile Technology Paper Topics

- Social Networking Essay Ideas

- Technology Essay Ideas

- Video Game Topics

- Chicago (A-D)

- Chicago (N-B)

IvyPanda. (2023, October 26). 108 Gambling Essay Topic Ideas & Examples. https://ivypanda.com/essays/topic/gambling-essay-topics/

"108 Gambling Essay Topic Ideas & Examples." IvyPanda , 26 Oct. 2023, ivypanda.com/essays/topic/gambling-essay-topics/.

IvyPanda . (2023) '108 Gambling Essay Topic Ideas & Examples'. 26 October.

IvyPanda . 2023. "108 Gambling Essay Topic Ideas & Examples." October 26, 2023. https://ivypanda.com/essays/topic/gambling-essay-topics/.

1. IvyPanda . "108 Gambling Essay Topic Ideas & Examples." October 26, 2023. https://ivypanda.com/essays/topic/gambling-essay-topics/.

Bibliography

IvyPanda . "108 Gambling Essay Topic Ideas & Examples." October 26, 2023. https://ivypanda.com/essays/topic/gambling-essay-topics/.

Presentations made painless

- Get Premium

126 Gambling Essay Topic Ideas & Examples

Inside This Article

Gambling is a popular pastime that has been around for centuries. Whether it's placing bets on sports games, playing poker at a casino, or buying lottery tickets, the thrill of risking money in the hopes of winning big is something that many people enjoy.

If you're looking for essay topics related to gambling, you're in luck. We've compiled a list of 126 gambling essay topic ideas and examples to help inspire your next paper. From the ethics of gambling to the impact of online gambling on society, there are plenty of angles to explore in this fascinating topic.

- The history of gambling

- The psychology of gambling addiction

- The ethics of gambling

- The impact of gambling on society

- The economics of gambling

- The role of luck in gambling

- The legality of online gambling

- The relationship between gambling and crime

- The effects of gambling on mental health

- The role of gambling in popular culture

- The impact of gambling on families

- The regulation of gambling

- The social stigma of gambling

- The role of gambling in politics

- The impact of gambling on the economy

- The link between gambling and substance abuse

- The role of gambling in sports

- The impact of gambling on indigenous communities

- The relationship between gambling and religion

- The effects of gambling advertising

- The impact of gambling on tourism

- The relationship between gambling and technology

- The role of gambling in education

- The impact of gambling on the environment

- The link between gambling and mental illness

- The role of gambling in history

- The impact of gambling on the brain

- The relationship between gambling and poverty

- The effects of gambling on relationships

- The role of gambling in the criminal justice system

- The impact of gambling on youth

- The link between gambling and suicide

- The role of gambling in healthcare

- The impact of gambling on the elderly

- The relationship between gambling and gender

- The effects of gambling on personal finances

- The role of gambling in international relations

- The impact of gambling on education

- The link between gambling and public health

- The role of gambling in social welfare

- The impact of gambling on mental health services

- The relationship between gambling and social services

- The effects of gambling on community development

- The role of gambling in urban planning

- The impact of gambling on rural communities

- The link between gambling and economic development

- The role of gambling in environmental conservation

- The impact of gambling on cultural heritage

- The relationship between gambling and human rights

- The effects of gambling on social justice

- The role of gambling in international development

- The impact of gambling on global health

- The link between gambling and international trade

- The role of gambling in sustainable development

- The impact of gambling on climate change

- The relationship between gambling and poverty reduction

- The effects of gambling on gender equality

- The role of gambling in conflict resolution

- The impact of gambling on peacebuilding

- The link between gambling and human security

- The role of gambling in disaster response

- The impact of gambling on humanitarian aid

- The relationship between gambling and international law

- The effects of gambling on global governance

- The role of gambling in international organizations

- The impact of gambling on regional cooperation

- The link between gambling and international relations

- The role of gambling in diplomacy

- The impact of gambling on conflict prevention

- The relationship between gambling and peacekeeping

- The effects of gambling on peacebuilding

- The role of gambling in post-conflict reconstruction

- The impact of gambling on transitional justice

- The link between gambling and human rights

- The role of gambling in international criminal justice

- The impact of gambling on international humanitarian law

- The relationship between gambling and international human rights law

- The effects of gambling on international refugee law

- The role of gambling in international environmental law

- The impact of gambling on international trade law

- The link between gambling and international investment law

- The role of gambling in international economic law

- The impact of gambling on international financial law

- The relationship between gambling and international banking law

- The effects of gambling on international tax law

- The role of gambling in international competition law

- The impact of gambling on international antitrust law

- The link between gambling and international intellectual property law

- The role of gambling in international labor law

- The impact of gambling on international human rights law

Want to create a presentation now?

Instantly Create A Deck

Let PitchGrade do this for me

Hassle Free

We will create your text and designs for you. Sit back and relax while we do the work.

Explore More Content

- Privacy Policy

- Terms of Service

© 2023 Pitchgrade

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- Published: 04 February 2021

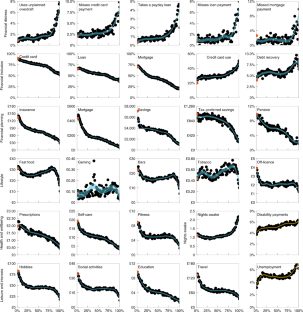

The association between gambling and financial, social and health outcomes in big financial data

- Naomi Muggleton ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-6462-3237 1 , 2 , 3 ,

- Paula Parpart 2 , 3 , 4 ,

- Philip Newall ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-1660-9254 5 , 6 ,

- David Leake 3 ,

- John Gathergood ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-0067-8324 7 &

- Neil Stewart ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-2202-018X 2

Nature Human Behaviour volume 5 , pages 319–326 ( 2021 ) Cite this article

3962 Accesses

73 Citations

291 Altmetric

Metrics details

- Human behaviour

- Social policy

Gambling is an ordinary pastime for some people, but is associated with addiction and harmful outcomes for others. Evidence of these harms is limited to small-sample, cross-sectional self-reports, such as prevalence surveys. We examine the association between gambling as a proportion of monthly income and 31 financial, social and health outcomes using anonymous data provided by a UK retail bank, aggregated for up to 6.5 million individuals over up to 7 years. Gambling is associated with higher financial distress and lower financial inclusion and planning, and with negative lifestyle, health, well-being and leisure outcomes. Gambling is associated with higher rates of future unemployment and physical disability and, at the highest levels, with substantially increased mortality. Gambling is persistent over time, growing over the sample period, and has higher negative associations among the heaviest gamblers. Our findings inform the debate over the relationship between gambling and life experiences across the population.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Access Nature and 54 other Nature Portfolio journals

Get Nature+, our best-value online-access subscription

24,99 € / 30 days

cancel any time

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 12 digital issues and online access to articles

111,21 € per year

only 9,27 € per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on Springer Link

- Instant access to full article PDF

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

Determinants of behaviour and their efficacy as targets of behavioural change interventions

Alzheimer’s disease risk reduction in clinical practice: a priority in the emerging field of preventive neurology

Adults who microdose psychedelics report health related motivations and lower levels of anxiety and depression compared to non-microdosers

Data availability.

The data that support the findings of this study are available from LBG but restrictions apply to the availability of these data, which were used under license for the current study, and so are not publicly available. Data are available from the authors upon reasonable request and with permission of LBG.

Code availability

Data were extracted from LBG databases using Teradata SQL Assistant (v.15.10.1.9). Data analysis was conducted using R (v.3.4.4). The SQL code that supports the analysis is commercially sensitive and is therefore not publicly available. The code is available from the authors upon reasonable request and with permission of LBG. The R code that supports this analysis can be found at github.com/nmuggleton/gambling_related_harm . Commercially sensitive code has been redacted. This should not affect the interpretability of the code.

Schwartz, D. G. Roll the Bones: The History of Gambling (Winchester Books, 2013).

Supreme Court of the United States. Murphy, Governor of New Jersey et al. versus National Collegiate Athletic Association et al. No. 138, 1461 (2018).

Industry Statistics (Gambling Commission, 2019); https://www.gamblingcommission.gov.uk/PDF/survey-data/Gambling-industry-statistics.pdf

Cassidy, R. Vicious Games: Capitalism and Gambling (Pluto Press, 2020).

Orford, J. The Gambling Establishment: Challenging the Power of the Modern Gambling Industry and its Allies (Routledge, 2019).

Duncan, P., Davies, R. & Sweney, M. Children ‘bombarded’ with betting adverts during World Cup. The Guardian https://www.theguardian.com/media/2018/jul/15/children-bombarded-with-betting-adverts-during-world-cup (15 July 2018).

Hymas, C. Church of England backs ban on gambling adverts during live sporting events. The Telegraph https://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/2018/10/08/church-england-backs-ban-gambling-adverts-live-sporting-events/ (10 August 2018).

McGee, D. On the normalisation of online sports gambling among young adult men in the UK: a public health perspective. Public Health 184 , 89–94 (2020).

Article CAS Google Scholar

Editorial. Science has a gambling problem. Nature 553 , 379 (2018).

National Gambling Strategy (Gambling Commission, 2019); https://www.gamblingcommission.gov.uk/news-action-and-statistics/News/gambling-commission-launches-new-national-strategy-to-reduce-gambling-harms

van Schalkwyk, M. C. I., Cassidy, R., McKee, M. & Petticrew, M. Gambling control: in support of a public health response to gambling. The Lancet 393 , 1680–1681 (2019).

Article Google Scholar

Wardle, H., Reith, G., Langham, E. & Rogers, R. D. Gambling and public health: we need policy action to prevent harm. BMJ 365 , l1807 (2019).

Volberg, R. A. Fifteen years of problem gambling prevalence research: what do we know? Where do we go? J. Gambl. Issues https://doi.org/10.4309/jgi.2004.10.12 (2004).

Select Committee on the Social and Economic Impact of the Gambling Industry. Corrected Oral Evidence: Social and Economic Impact of the Gambling Industry (UK Parliament, 2019); https://committees.parliament.uk/oralevidence/15/html/

Wardle, H. et al. British Gambling Prevalence Survey 2010 (National Centre for Social Research, 2011); https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/243515/9780108509636.pdf

Smith, G., Hodgins, D. & Williams, R. Research and Measurement Issues in Gambling Studies (Emerald, 2007).

Harrison, G. W., Lau, M. I. & Ross, D. The risk of gambling problems in the general population: a reconsideration. J. Gambl. Stud. 36 , 1133–1159 (2020).

Wood, R. T. & Williams, R. J. ‘How much money do you spend on gambling?’ The comparative validity of question wordings used to assess gambling expenditure. Int. J. Soc. Res. Methodol. 10 , 63–77 (2007).

Toneatto, T., Blitz-Miller, T., Calderwood, K., Dragonetti, R. & Tsanos, A. Cognitive distortions in heavy gambling. J. Gambl. Stud. 13 , 253–266 (1997).

Wardle, H., John, A., Dymond, S. & McManus, S. Problem gambling and suicidality in England: secondary analysis of a representative cross-sectional survey. Public Health 184 , 11–16 (2020).

Karlsson, A. & Håkansson, A. Gambling disorder, increased mortality, suicidality, and associated comorbidity: a longitudinal nationwide register study. J. Behav. Addict. 7 , 1091–1099 (2018).

Wong, P. W. C., Chan, W. S. C., Conwell, Y., Conner, K. R. & Yip, P. S. F. A psychological autopsy study of pathological gamblers who died by suicide. J. Affect. Disord. 120 , 213–216 (2010).

LaPlante, D. A., Nelson, S. E., LaBrie, R. A. & Shaffer, H. J. Stability and progression of disordered gambling: lessons from longitudinal studies. Can. J. Psychiatry 53 , 52–60 (2008).

Wohl, M. J. & Sztainert, T. Where did all the pathological gamblers go? Gambling symptomatology and stage of change predict attrition in longitudinal research. J. Gambl. Stud. 27 , 155–169 (2011).

Browne, M., Goodwin, B. C. & Rockloff, M. J. Validation of the Short Gambling Harm Screen (SGHS): a tool for assessment of harms from gambling. J. Gambl. Stud. 34 , 499–512 (2018).

Browne, M. et al. Assessing Gambling-related Harm in Victoria: A Public Health Perspective (Victorian Responsible Gambling Foundation, 2016).

Canale, N., Vieno, A. & Griffiths, M. D. The extent and distribution of gambling-related harms and the prevention paradox in a British population survey. J. Behav. Addict. 5 , 204–212 (2016).

Salonen, A. H., Hellman, M., Latvala, T. & Castrén, S. Gambling participation, gambling habits, gambling-related harm, and opinions on gambling advertising in Finland in 2016. Nordisk Alkohol Nark. 35, 215–234 (2018).

Langham, E. et al. Understanding gambling related harm: a proposed definition, conceptual framework, and taxonomy of harms. BMC Public Health 16 , 80 (2016).

Wardle, H., Reith, G., Best, D., McDaid, D. & Platt, S. Measuring Gambling-related Harms: A Framework for Action (Gambling Commission, 2018).

Browne, M. & Rockloff, M. J. Prevalence of gambling-related harm provides evidence for the prevention paradox. J. Behav. Addict. 7 , 410–422 (2018).

Collins, P., Shaffer, H. J., Ladouceur, R., Blaszszynski, A. & Fong, D. Gambling research and industry funding. J. Gambl. Stud. 36 , 1–9 (2019).

Google Scholar

Delfabbro, P. & King, D. L. Challenges in the conceptualisation and measurement of gambling-related harm. J. Gambl. Stud. 35 , 743–755 (2019).

Browne, M. et al. What is the harm? Applying a public health methodology to measure the impact of gambling problems and harm on quality of life. J. Gambl. Issues https://doi.org/10.4309/jgi.2017.36.2 (2017).

Markham, F., Young, M. & Doran, B. The relationship between player losses and gambling-related harm: evidence from nationally representative cross-sectional surveys in four countries. Addiction 111 , 320–330 (2016).

Markham, F., Young, M. & Doran, B. Gambling expenditure predicts harm: evidence from a venue-level study. Addiction 109 , 1509–1516 (2014).

Blaszczynski, A., Ladouceur, R. & Shaffer, H. J. A science-based framework for responsible gambling: the Reno model. J. Gambl. Stud. 20 , 301–317 (2004).

Rose, G. The Strategy of Preventive Medicine (Oxford Univ. Press, 1992).

Improving the Financial Health of the Nation (Financial Inclusion Commission, 2015); https://www.financialinclusioncommission.org.uk/pdfs/fic_report_2015.pdf

Download references

Acknowledgements

We thank A. Trendl and H. Wardle for comments on an earlier draft of this manuscript. We thank R. Burton, Z. Clarke, C. Henn, J. Marsden, M. Regan, C. Sharpe and M. Smolar from Public Health England and L. Balla, L. Cole, K. King, P. Rangeley, H. Rhodes, C. Rogers and D. Taylor from the Gambling Commission for providing feedback on a presentation of this work. We thank A. Akerkar, D. Collins, T. Davies, D. Eales, E. Fitzhugh, P. Jefferson, T. Bo Kim, M. King, A. Lazarou, M. Lien and G. Sanders for their assistance. We thank the Customer Vulnerability team, with whom we worked as part of their ongoing strategy to help vulnerable customers. We acknowledge funding from LBG, who also provided us with the data but had no other role in study design, analysis, decision to publish or preparation of the manuscript. The views and opinions expressed are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of LBG, its affiliates or its employees. We also acknowledge funding from Economic and Social Research Council (ESRC) grants nos. ES/P008976/1 and ES/N018192/1. The ESRC had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish or preparation of the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Department of Social Policy and Intervention, University of Oxford, Oxford, UK

Naomi Muggleton

Warwick Business School, University of Warwick, Coventry, UK

Naomi Muggleton, Paula Parpart & Neil Stewart

Applied Science, Lloyds Banking Group, London, UK

Naomi Muggleton, Paula Parpart & David Leake

Department of Experimental Psychology, University of Oxford, Oxford, UK

Paula Parpart

Warwick Manufacturing Group, University of Warwick, Coventry, UK

- Philip Newall

School of Health, Medical and Applied Sciences, CQ University, Melbourne, Australia

School of Economics, University of Nottingham, Nottingham, UK

John Gathergood

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

P.P. and P.N. proposed the initial concept. All authors contributed to the design of the analysis and the interpretation of the results. J.G. and N.S. wrote the initial draft; all authors contributed to the revision. N.M. and P.P. constructed variables and N.M. prepared all figures and tables. D.L. established collaboration with LBG. D.L., J.G. and N.S. secured funding for the research. P.N. conducted a review of the existing literature.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Naomi Muggleton .

Ethics declarations

Competing interests.

N.M. was previously, and D.L. is currently, an employee of LBG. P.P. was previously a contractor at LBG. They do not, however, have any direct or indirect interest in revenues accrued from the gambling industry. P.N. was a special advisor to the House of Lords Select Committee Enquiry on the Social and Economic Impact of the Gambling Industry. In the last 3 years, P.N. has contributed to research projects funded by GambleAware, Gambling Research Australia, NSW Responsible Gambling Fund and the Victorian Responsible Gambling Foundation. In 2019, P.N. received travel and accommodation funding from the Spanish Federation of Rehabilitated Gamblers and in 2020 received an open access fee grant from Gambling Research Exchange Ontario. All other authors have no competing interests.

Additional information

Peer review information Peer reviewer reports are available. Primary Handling Editor: Aisha Bradshaw.

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Supplementary information.

Supplementary Tables 1–24.

Reporting Summary

Peer review information, rights and permissions.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Muggleton, N., Parpart, P., Newall, P. et al. The association between gambling and financial, social and health outcomes in big financial data. Nat Hum Behav 5 , 319–326 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41562-020-01045-w

Download citation

Received : 26 March 2020

Accepted : 23 December 2020

Published : 04 February 2021

Issue Date : March 2021

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1038/s41562-020-01045-w

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

This article is cited by

Differences amongst estimates of the uk problem gambling prevalence rate are partly due to a methodological artefact.

- Philip W. S. Newall

- Leonardo Weiss-Cohen

- Peter Ayton

International Journal of Mental Health and Addiction (2024)

When Vegas Comes to Wall Street: Associations Between Stock Price Volatility and Trading Frequency Amongst Gamblers

- Iain Clacher

Towards an Active Role of Financial Institutions in Preventing Problem Gambling: A Proposed Conceptual Framework and Taxonomy of Financial Wellbeing Indicators

- Nathan Lakew

- Jakob Jonsson

- Philip Lindner

Journal of Gambling Studies (2024)

Skill-Based Electronic Gaming Machines: Features that Mimic Video Gaming, Features that could Contribute to Harm, and Their Potential Attraction to Different Groups

- Matthew Rockloff

- Georgia Dellosa

A Double-Edged-Sword Effect of Overplacement: Social Comparison Bias Predicts Gambling Motivations and Behaviors in Chinese Casino Gamblers

- Gui-Hai Huang

- Zhu-Yuan Liang

Quick links

- Explore articles by subject

- Guide to authors

- Editorial policies

Sign up for the Nature Briefing newsletter — what matters in science, free to your inbox daily.

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Springer Nature - PMC COVID-19 Collection

An Overview of the Economics of Sports Gambling and an Introduction to the Symposium

Victor matheson.

College of the Holy Cross, Worcester, USA

Gambling in the Ancient World

Gambling likely predates recorded history. The casting of lots (from which we get the modern term “lottery”) is mentioned both in the Old and New Testaments of the Bible, most famously when Roman soldiers cast lots for the clothes of Jesus during his crucifixion. In Greek mythology, Hades, Poseidon, and Zeus divided the heavens, the seas, and the underworld through a game of chance.

Organized sports also have a long history. The Ancient Olympic Games date back to 776 BCE and persisted until 394 AD. The Circus Maximum in Rome, the home of horse and chariot racing events as well as gladiatorial contests for over one thousand years, was originally constructed around 500 BCE, and the Colosseum in Rome began hosting sporting events including gladiator fights in 80 AD. Variations of the ball game Pitz were played in Mesoamerica for nearly 3000 years beginning as early as 1400 BCE (Matheson 2019 ).

Given the prevalence of both sporting contests and gambling across many ancient civilizations, it is natural to conclude that the combined activity of sports gambling also has a long history. And, indeed it is widely reported that gambling was a popular activity at the Olympics and other ancient Panhellenic events in Greece and at the racing and fighting contests in ancient Rome. Problems associated with gambling were also widely reported. As early as 388 BCE, the boxer Eupolus of Thessaly was known to have paid opponents to throw fights in the Olympics. Rampant gambling in Rome led Caesar Augustus (c. BCE 20) to limit the activity to only a week-long festival called “Saturnalia” celebrated around the time of the winter solstice, while Emperor Commodus (AD 192) turned the royal palace into a casino and bankrupted the Roman Empire along the way (Matheson et al. 2018 ).

Just as in the modern day, gambling was often looked down upon by societal leaders in antiquity. Horace (Ode III., 24; 23 BCE) wrote, “The young Roman is no longer devoted to the manly habits of riding and hunting; his skills seem to develop more in the games of chances forbidden by law.” Juvenal (Satire I, 87; 101 AD), well-known for coining the term “bread and circuses” wrote, “Never has the torrent of vice been to irresistible or the depths of avarice more absorbing, or the passion for gambling more intense. None approach nowadays the gambling table with the purse; they must carry their strongbox. What can we think of these profligates more ready to lose 100,000 than to give a tunic to a slave dying with cold.” (Matheson 2019 ).

Gambling in Renaissance and Pre-industrial Revolution Europe

Gambling in Europe persisted into the Middle Ages and Renaissance. For example, although the true origins of the famous columns in Venice’s Piazza San Marco are lost to the mysteries of time, at least one history suggests they were erected around 1127 by Nicholas Barattieri, who was rewarded for this task by the local government with an exclusive right to operate a gaming table between the columns, an activity otherwise officially prohibited in the Republic (Schiavon 2020 ).

However, without the large sporting events of the ancient world, gambling turned more toward to precursors of modern casino games. Indeed, the gambling that occurred in the “small houses” or “casini” of the city of Venice is the origin of the modern term “casino,” and in 1638 Il Ridotto, “the Private Room,” became the first public, legal casino in the region (Schwarz 2006 ).

Until the formation of professional sports leagues in the mid- to late nineteenth century, horse racing was the predominant type of sports gambling across Europe and North America. The Newmarket Racecourse near Cambridge, UK, was founded in 1636 although races at the location date to even earlier. The racetrack was frequented by King Charles II earning horse racing the title of “the Sport of Kings” (Black 1891 ). The first racetrack in North America was established on Long Island in 1665, and horse racing has persisted in the USA since that time.

Prior to the mid-1800s, bets in horseracing were handled by bookmakers who set odds on individual races. This carries risk for the bookmaker who may be forced to pay out large winning bets as well as the bettor who may find that the bookmaker lacks the funds to cover all payouts. This problem was solved in 1867 in Paris when Joseph Oller, who later went on to open the famous Parisian nightclub the Moulin Rouge, developed pari-mutuel betting.

Under pari-mutuel betting, the returns are based not on independent odds set by a bookmaker but instead are endogenously generated by the gamblers themselves based upon the number and size of the bets made on various race participants (Canymeres 1946 ). This betting system rapidly became wildly popular for racing in Europe and USA and remains the standard for horse racing today throughout the world.

Gambling Throughout US History

Gambling was a common activity throughout colonial and early American history. Lotteries funded activities such as the original European settlement at Jamestown, the operations of prestigious universities such as Harvard and Princeton, and construction of historic Faneuil Hall in Boston. Card rooms were not unusual at taverns and roadhouses across the country, and the activity moved west onto riverboats and into saloons as westward expansion occurred during the 1800s (Grote and Matheson 2017 ).

However, the late 1800s and early 1900 witnessed a widespread decline the legality of all types of gambling throughout the USA. In the sports realm, by 1900 betting on horse races was made illegal except in Kentucky and Maryland, states that to this day host two of the three Triple Crown events in American horseracing, the Kentucky Derby and the Preakness Stakes. States began to relegalize gambling on horse racing in the 1930s as a method of economic stimulus during the Great Depression. Total horse racing handle peaked in the 1970s and has generally declined since that time due to increased competition from alternative forms of gambling such as state lotteries and casinos (and, in fact, many racetracks nationwide, known as “racinos,” are permitted to offer alternative forms of gambling such as slot machines on their grounds (Nash 2009 )). In 2019, horse racing’s handle in the USA totaled $11.0 billion (Jockey Club 2020 ).

The birth of professional sports leagues in the USA also gave immediate rise to new betting opportunities, as well as problems associated with corruption. The oldest professional league in the USA, baseball’s National League, formed in 1876, and by 1877 the Louisville Grays ended the season mired in a betting scandal and ceased operations. Similarly in football, the Ohio League, a forerunner to the modern National Football League (NFL), began play in 1903, and by 1906, the league was embroiled in a match fixing scandal between the Canton Bulldogs and the Massillon Tigers (Grote and Matheson 2017 ).

During the early years of professional sports leagues in the USA, betting on games, although generally illegal like most gambling in the period, was common either through direct bets made with bookies or through “pool cards” allowing gamblers to bet on a slate of games. Nevada, which in 1931 became the first state to relegalize most forms of gambling, authorized sports gambling in 1949, but high tax rates on wagers prevented major casinos from running sports books until 1974. Following the elimination of a 10% tax on sports gambling revenues in the state, the sport betting handle rose dramatically from $825,767 in 1973 to $3,873,217 in 1974, to $26,170,328 in 1975 (Grote and Matheson 2017 ). By 2019, Nevada’s 192 sportsbooks took in $5.3 billion in wagers or roughly 2.7% of total gaming revenues for the state (Nevada Gaming Control Board 2019 ).

While Nevada remained the only state offering full sports books, Montana, Oregon, and Delaware all offered pool cards through their state lotteries beginning in the 1970s. Montana first offered legal pool cards in 1974. Delaware followed in 1976 (even winning a court case against the NFL for the right to offer sports gambling), but its games folded in the following year due to difficulties in adhering to the state’s statutory guidelines about lottery contributions to state coffers. The Oregon Lottery sold NFL pool cards from 1998 to 2007 and National Basketball Association (NBA) game tickets in 1998 and 1999 (although the NBA ticket did not include games featuring Portland’s local NBA team). Pressure from the National Collegiate Athletic Association (NCAA) eventually led the state to terminate its sports gambling offerings under the threat of losing the opportunity to host NCAA post-season men’s basketball tournament (March Madness) games (Grote and Matheson 2017 ).

The Professional and Amateur Sports Protection Act (PAPSA), passed in 1992, prohibited states from legalizing sports gambling in any form including lotteries, casinos, and tribal casinos while grandfathering in the four states with existing sports gambling operations. In mid 2010s, the state of New Jersey, in an effort to revive its flagging casinos in Atlantic City, sued to overturn PAPSA, and in May 2018, the US Supreme Court declared PAPSA unconstitutional. While this ruling did not legalize sports gambling in any states, it did allow states the option to legalize sports gambling if they so choose. This symposium examines some of the economic issues facing the sports gambling industry as the American market opens up.

Issues Facing the New Sports Gambling Industry

The first and perhaps easiest question facing the industry is how quickly and how widely will sports gambling be adopted by states? Here it seems clear that sports gambling will follow the pattern seen in lottery and casino adoption, although almost certainly at a much faster pace. As noted by Garrett and Marsh ( 2002 ), once states began to legalize state lotteries, neighboring states began to feel pressure to legalize their own state games or otherwise lose consumer spending to lottery players crossing the border to buy tickets.

By 2020, this pressure had led all but 6 states to adopt lotteries after the first state lottery was reestablished in New Hampshire in 1964. Among the holdouts, Alaska and Hawaii are protected geographically from cross-border purchases, Nevada’s powerful gambling industry has successfully prevented the adoption of a state-sponsored competitor, and conservative religious cultures in Alabama, Mississippi, and Utah have stopped lotteries there. (Religious concerns have not stopped Mississippi from legalizing sports gambling, however. Perhaps God just really wants to put a few bucks down on Ole Miss to upset the Tide this year.)

With respect to sports gambling, New Jersey and Delaware legalized the activity immediately upon the Court’s decision in 2018, and many states followed suit. By the end of 2020, 20 states and the District of Columbia had legalized sports gambling, 6 had legalized sports gambling but were pending launch, and over 20 more states were considering legislation (Rodenberg 2020 ). It appears that sports gambling will soon be legal nearly nationwide.

The next big question facing the industry is assessing the potential size of the sports betting market. If sports wagering is restricted to in-person betting at existing casinos, the impact of nationwide legalization is likely to be quite modest. Extrapolating Nevada’s sport wagering data to the national casino market suggests that nationwide legalization might lead to as much as $20 billion in annual wagers and just under $1 billion in net casino revenues. While these figures may seem high, they pale in comparison to gambling figures in the UK where sports betting has been legal (although highly regulated) since 1960 and is widely available through over 8300 (as of March 2019) small, commercial betting shops spread throughout the country as well as through online betting sites.

In the most recent fiscal year prior to shutdowns caused by the COVID-19 pandemic, in-person betting shops in the UK generated $3.7 billion and online gambling generated another $2.8 billion in net gambling revenues (UK Gambling Commission 2020 ). This implies that UK bettors placed roughly $130 billion in wagers in 2019 or about $2000 per person in the country. If industry were to achieve a similar level of popularity in the US market, this would suggest over $600 billion in annual wagers and $32 billion in net sport gambling revenue. The $32 billion figure would be roughly twice the net gambling revenue generated by state lotteries across the country and slightly less than the $42 billion in net casino gaming revenue generated across the USA. Such revenue figures would likely only be possible with widespread adoption of legalized mobile sports gambling as well as within-game betting on individual plays as opposed to wagering solely on game outcomes.

Obviously, another major question facing the industry is the extent to which expanded access to sports gambling will bring in new players to the gambling industry overall or whether it will simply cannibalize existing gambling options such as state lotteries, horse racing, or casino gaming. The first paper in this symposium examines this topic by analyzing the determinants of sport gambling handle and its effects on other casino gaming at West Virginia casinos during roughly the first year of legalized sports betting in the state (Humpheys 2021). Brad Humphreys finds that the introduction of sports gambling seems to have significantly decreased overall state gaming tax revenues as gains from sport gambling taxes were far outweighed by decreases in tax revenues from video lottery terminals.

Of course, even if the problem of cannibalization is avoided by sports gambling attracting a new customer base, this is not without its own set of problems as sports wagering may introduce an entirely new population to the problems associated with pathological gambling and problem gaming (McGowan 2014 ). The second paper in this symposium examines health outcomes in Canada related to participation in gambling activities (Humphreys et al. 2021 ). Brad Humphreys, John Nyman, and Jane Ruseski show that recreational gambling has either no effect or even actually reduces the probability of having certain chronic health conditions and has a positive impact on life satisfaction suggesting the possibility that expanded sport gambling in the USA may not be associated with significant adverse health outcomes.

Legalized sports gambling is certain to bring about winners and losers. As noted above, depending on the level of cannibalization, other forms of gambling are likely to be losers such as horse racing, which is likely to continue its long-term decline in gambling handle (Nash 2009 ), and potentially casino gaming as identified by Humphreys ( 2021 ) in this symposium. On the other hand, sports book operators and mobile application developers are likely winners, so casinos themselves may either be either winners or losers in sports gambling legalization. It is interesting to note that established casinos have not been the only players to enter the online sports gambling market. In many states, the companies FanDuel and DraftKings, who prior to sports gambling legalization operated online fantasy football competitions of controversial legality, have already been able to leverage their fan bases in the online fantasy sports gaming communities into more traditional online sports gambling opportunities.

The sports leagues themselves may also be either winners or losers. Historically in the USA, leagues strongly opposed legal sports betting due to the potential for corruption. The history of sports in the USA is littered with betting scandals from the earliest days of the previously mentioned Louisville Grays and Canton Bulldogs to the infamous 1919 “Black Sox” World Series scandal to the 1948 NCAA basketball point-shaving scheme to the more recent actions of Major League Baseball (MLB) player and manager Pete Rose or NBA referee Tim Donaghy.

More recently, however, leagues have become more supportive of sports betting. In part, leagues acknowledge that legal betting markets make it easier for regulators to uncover suspicious betting behavior that could suggest corruption. More importantly, teams and leagues have also slowly recognized the potential for higher fan interest if fans have the opportunity to gamble on games. There is no doubt that the NCAA can attribute a significant portion of its 23-year, $19.6 billion television contract for March Madness on the popularity of “bracket pools,” and likewise the NFL understands the degree to which the explosion of fantasy football leagues has increased the popularity of its games. Humphreys et al. ( 2013 ) developed evidence of a significant correlation between betting and television viewership for regular season men’s NCAA basketball games.

Furthermore, the dramatic increase in professional athlete salaries over the past several decades in the USA has reduced worries of corruption. It is highly unlikely that star players in any major US league would jeopardize their massive earning potential as an athlete by accepting a bribe to alter a game outcome (and non-star players to whom a bribe could potentially be profitable are rarely in a position to influence games).

Those sports that remain at more significant risk to corruption are those with a high level of fan interest but low player salaries. This describes the working conditions of athletes prior to free-agency in the USA such as during the 1919 Black Sox scandal, referees like Tim Donaghy, and players in minor leagues or small national leagues as well as cricket players prior to the relatively recent formation of the Indian Premier League. It also describes the conditions of college athletes in the USA as the NCAA has successfully operated a cartel restricting the ability of even top college players from earning money as a player despite playing for teams generating millions or tens of millions of dollars annually for their host institutions. Thus, it comes as no surprise that the NCAA remains adamantly opposed to sport gambling in contrast to the major professional leagues in the USA.

Sports leagues are naturally eager to take steps to protect themselves against potential corruption in the wake of expanded gambling opportunities. The third paper in the symposium (Depken and Gandar 2021 ) explores the topic of integrity fees, payments by sports books to leagues, supposedly to pay for monitoring to ensure against match fixing. Craig Depken and John Gandar find evidence that integrity fees might influence sports books to establish lines that would minimize the chances for payouts in certain game situations.

Finally, legalized sports gambling will provide researchers with troves of new data to analyze one of the oldest questions in gambling economics: are sports betting markets efficient? The final paper in this symposium provides an excellent example of this type of research (Brymer et al. 2021 ). Rhett Brymer, Ryan M. Rodenberg, Huimiao Zheng, and Tim R. Holcomb examine whether referees in college football’s major conferences can be shown to have particular biases and if these biases are appropriately accounted for in the gambling markets. Studies like these will remain a fertile area for continued economic research.

As guest editor, I wish to thank Eastern Economic Journal co-editors Cynthia Bansak and Allan Zebedee, participants in the sports economics sessions at the 39th annual Eastern Economic Association Conference in New York City, February 2019, and numerous anonymous referees for their assistance in putting together this symposium. Most importantly, thanks go out to Eastern Economic Association Vice President Brad Humphreys who both proposed this symposium and collected and reviewed the participating papers. His name should really be on this guest editor’s introduction, but I guess he will have to settle to being co-author on two fine contributions within this symposium.

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

- Black Robert. The Jockey Club and Its Founders: In Three Periods. London: Smith, Elder; 1891. [ Google Scholar ]

- Brymer, Rhett, Ryan M. Rodenberg, Huimiao Zheng, and Tim R. Holcomb. 2021. College Football Referee Bias and Sports Betting Impact. Eastern Economic Journal. 10.1057/s41302-020-00180-6.

- Canymeres, Ferran. 1946. Oller: L’Homme de la belle époque . Les Editions Universelles, Paris. Translated and summarized by the University of Auckland. https://www.cs.auckland.ac.nz/historydisplays/SecondFloor/Totalisators/ToteHistory/BookSummary.pdf . Accessed 1 November 2020.

- Depken, Craig A. and John Gandar. 2021. Integrity Fees in Sports Betting Markets. Eastern Economic Journal . 10.1057/s41302-020-00179-z. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ]

- Garrett Thomas A, Marsh Thomas L. The Revenue Impacts of Cross-Border Lottery Shopping in the Presence of Spatial Autocorrelation. Regional Science and Urban Economics. 2002; 32 (4):501–519. doi: 10.1016/S0166-0462(01)00089-8. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Grote Kent, Matheson Victor. Should Gambling Markets be Privatized? An Examination of State Lotteries in the United States. In: Rodríguez Plácido, Humphreys Brad, Simmons Robert., editors. Sports and Betting. London: Edward Elgar; 2017. pp. 21–37. [ Google Scholar ]

- Humphreys, Brad R. 2021. Legalized Sports Betting, VLT Gambling, and State Gambling Revenues: Evidence from West Virginia. Eastern Economic Journal. 10.1057/s41302-020-00178-0. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ]

- Humphreys, Brad R., John A. Nyman, and Jane E. Ruseski. 2021. The Effect of Recreational Gambling on Health and Well-Being. Eastern Economic Journal . 10.1057/s41302-020-00181-5.

- Humphreys Brad R, Paul Rodney J, Weinbach Andrew P. Consumption Benefits and Gambling: Evidence from the NCAA Basketball Betting Market. Journal of Economic Psychology. 2013; 39 (2):376–386. doi: 10.1016/j.joep.2013.05.010. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Jockey Club. 2020. Pari-mutuel Handle . http://www.jockeyclub.com/default.asp?section=FB&area=8 . Accessed 1 November 2020.

- Matheson Victor. The Rise and Fall (and Rise and Fall) of the Summer Olympics as an Economic Driver. In: Wilson John, Pomfret Richard., editors. Historical Perspectives on Sports Economics: Lessons from the Field. London: Edward Elgar; 2019. pp. 52–66. [ Google Scholar ]

- Matheson Victor, Schwab Daniel, Koval Patrick. Corruption in the Bidding, Construction, and Organization of Mega-Events: An Analysis of the Olympics and World Cup. In: Breuer Markus, Forrest David., editors. The Palgrave Handbook on the Economics of Manipulation in Professional Sports. New York: Palgrave McMillan; 2018. pp. 257–278. [ Google Scholar ]

- McGowan Richard. The Dilemma that is Sports Gambling. Gaming Law Review and Economics. 2014; 18 (7):670–678. doi: 10.1089/glre.2014.1875. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Nash, Betty Joyce. 2009. Sport of Kings: Horse Racing in Maryland . https://www.richmondfed.org/-/media/richmondfedorg/publications/research/econ_focus/2009/spring/pdf/economic_history.pdf .

- Nevada Gaming Control Board. 2019. Monthly Revenue Report, December 2019 . https://gaming.nv.gov/modules/showdocument.aspx?documentid=16490 .

- Rodenberg, Ryan. 2020. United States of sports betting: An updated map of where every state stands , ESPN.com. https://www.espn.com/chalk/story/_/id/19740480/the-united-states-sports-betting-where-all-50-states-stand-legalization .

- Schiavon, Alessia. 2020. Youth Committee of the Italian National Commission for UNESCO . https://artsandculture.google.com/exhibit/the-columns-of-san-marco-and-san-todaro-comitato-giovani-della-commissione-nazionale-italiana-per-l-unesco/2wIyGE9EqYPgIA?hl=en . Accessed 15 November 2020.

- Schwartz David G. Roll the Bones: The History of Gambling. New York: Gotham; 2006. [ Google Scholar ]

- UK Gambling Commission. 2020. Gambling Industry Statistics April 2015 to March 2019 . https://www.gamblingcommission.gov.uk/PDF/survey-data/Gambling-industry-statistics.pdf .

EDITORIAL article

Editorial: problem gambling: summarizing research findings and defining new horizons.

- 1 Institute of Psychology and Cognition Research, University of Bremen, Bremen, Germany

- 2 Department of Neurofarba, University of Florence, Florence, Italy

- 3 Faculty of Education and Rehabilitation Sciences, University of Zagreb, Zagreb, Croatia

- 4 University of Iceland, Reykjavik, Iceland

- 5 McGill University, Montreal, QC, Canada

Editorial on the Research Topic Problem Gambling: Summarizing Research Findings and Defining New Horizons

Introduction

More than a decade ago, Shaffer et al. (2006) reported that gambling-related research was growing at an exponential rate. Since that time, this trend appears to have continued, and much more is now known about this particular form of risky behavior. Nevertheless, there is still a general tendency to not perceive gambling as a potential danger for youth and other vulnerable populations.

The latest edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5) included “gambling disorder” as the only condition in the section “non-substance-related disorders.” Moreover, it was specified that this disorder can indeed occur in adolescence, young adulthood or even late adulthood. Despite this fact, theoretical and applied research on problem gambling especially with regard to adolescence and other risk groups still remains fragmentary. For this reason, we felt it to be important to organize a special research topic on gambling. The primary goals were to highlight the necessity of considering excessive gambling as a potential harmful activity, to summarize the state-of-art of international research on different aspects of the topic and to offer important novel findings relevant for advancing knowledge in the field of gambling. Taken together, the contributions can be classified into four broad categories: (1) youth gambling, (2) risk factors in adulthood, (3) measurement issues, and (4) clinical research.

Overview of Contributing Papers

In total, 18 papers are presented in this special issue. The first central domain refers to gambling among youth. Even though regulated forms of gambling are generally prohibited to minors, there is a considerable body of research that proves their involvement in gambling activities. A significant minority of adolescents even show gambling-related psychosocial problems ( Calado et al., 2017 ). In addition, several studies have explored risk and protective factors in childhood, adolescence or young adulthood for the development of problem gambling symptoms ( Dowling et al., 2017 ). Four papers in this issue have specifically focused on youth gambling, contributing to the current knowledge by exploring less studied psychosocial constructs or subpopulations and offering guidelines for the conception of interventions. From the broader social perspective, Canale et al. presented the first study with a large-scale nationally representative sample of adolescents to examine the effects of income inequality on adolescent gambling, concluding that wealth distribution may have an impact on youth gambling. Gender issues were raised with the study from Huic et al. focusing on gambling predictors of adolescent girls who are a much less studied population than boys. Furthermore, empirical findings from Nigro et al. with regard to different emotional and cognitive factors confirmed the impact of impulsivity and emotional distress on the development of youth problem gambling. Last but not least, Donati et al. addressed mindware problems (i.e., cognitive distortions) and their influence both on youth gambling as well as the conception of theoretically founded preventive interventions.

In addition, four papers shed light on specific risk constellations for the development and manifestation of gambling-related problems in adulthood. Based on representative data from Austria, Buth et al. tackled the question of whether certain risk factors are equally relevant for at-risk, problem, and disordered gamblers. Overall, their findings indicated that the included risk factors indeed differ between these gambling groups, suggesting the need for more tailored prevention and treatment strategies. In contrast to this approach, the study by Hing et al. aimed at identifying risk factors for three forms of problematic online gambling [i.e., electronic gaming machines (EGMs), sports betting, race betting]. While the risk profiles of online sports bettors and race bettors were largely similar, a rather different pattern emerged for online EGM gamblers pointing again to the importance of differential activities in terms of prevention and intervention. Unique findings also stem from Olason et al. who conducted a population-based follow-up study in order to determine the impact of the economic crisis in Iceland on gambling behavior. Interestingly, past year problematic gambling figures did not change after the economic collapse. However, an increased participation in lotto and scratch tickets indicates that gambling forms with low initial stakes and large jackpots may then become more enticing, in particular for individuals suffering financial difficulties. In a very well-balanced opinion paper Zakiniaeiz et al. finally recalled the necessity to study gender differences in gambling patterns, especially with regard to preferred gambling forms, the onset of disordered gambling, co-occurring disorders and disorder progression.

Another important area in gambling research relates to measurement issues. In particular, the reliable and valid assessment of problem gambling patterns has received a considerable amount of attention for both adolescents ( Edgren et al., 2016 ) and adults ( Pickering et al., 2018 ). Five papers deal with the psychometric properties of novel measurement tools. Against the background that large-scale prevalence studies consistently represent high prevalence rates of gambling participation among youth (see above), two papers directly focus on this age cohort. While Stinchfield et al. developed and evaluated the psychometric properties of the Brief Adolescent Gambling Screen (BAGS), a three-item screen for adolescent problem gambling, Donati et al. tested the gender invariance of their Gambling Behavior Scale for Adolescents (GBS-A) applying item response theory. New tools that broadly aim at determining risk and protective factors associated with problem gambling in adults were also introduced. For example, Barbaranelli et al. reported the psychometric properties of the Multidimensional Gambling Self-Efficacy Scale (MGSES), an innovative scale to measure self-efficacy as a protective factor for problem gambling. In addition, Cowie et al. provided preliminary evidence for the predictive validity of the Gambling Cognitions Inventory (GCI) as a measure of cognitive distortions, showing its relationship to several gambling outcomes over a 1-month and a 6-month time period, respectively. In a similar vein, Jonsson et al. assessed the capacity of the different dimensions of the Jonsson-Abbott Scale (JAS) to predict increases in problem gambling risk levels as well as the onset of problem gambling over 1 year.

The final main subject of interest relates to clinical examinations of problem gambling. Researchers and treatment providers have sought to identify the underlying issues associated with problem gambling and have tried to identify both the barriers preventing individuals for seeking help and best practices in working with individuals with this disorder. Five informative papers have looked at this issue from multiple perspectives. Challet-Bouju et al. provided a systematic review of cognitive interventions highlighting that this common form of intervention represents a promising approach to gambling disorder management while Tremblay et al. documented the experiences of gamblers and their partners either individually or in couple therapy. Their conclusion was that both forms of treatment were effective but more positive experiences emerged for couple therapy. In yet another interesting paper, Gavriel-Fried and Rabayov examined the importance of self-stigma for individuals seeking treatment for gambling, alcohol or other substance use problems. They summarized that stigma among individuals with gambling problems tend to work in a similar way as among those individuals with an alcohol or drug problem. Jiménez-Murcia et al. analyzed the frequency of the co-occurrence of gambling disorders and food addiction. Their findings suggest that almost 10% of individuals having a gambling disorder concurrently experienced a food addiction. In addition, a far higher ratio of food addiction was found in women. Lastly, Giroux et al. provided a systematic review of online and mobile interventions for problem gambling, alcohol and drug use. While this may prove promising in the future, more rigorous research is necessary before definite conclusions can be reached. In sum, more research is clearly needed in understanding gambling disorders or problem gambling patterns before best practice treatment approaches can be identified. Clinicians and treatment providers are well aware that problem gamblers do not represent a homogenous group ( Blaszczynski and Nower, 2002 ) and that differential approaches may be required.

Overall, 94 different authors from 15 countries contributed to this special issue. We remain confident that these 18 papers significantly add to the understanding of problem gambling and will further stimulate high-quality gambling research in its many facets.

Author Contributions

All authors listed have made a substantial, direct and intellectual contribution to the work, and approved it for publication.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Blaszczynski, A., and Nower, L. (2002). A pathways model of problem and pathological gambling. Addiction 97, 487–499. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.2002.00015.x

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Calado, F., Alexandre, J., and Griffiths, M. D. (2017). Prevalence of adolescent problem gambling: a systematic review of research. J. Gambl. Stud . 33, 397–424. doi: 10.1007/s10899-016-9627-5

Dowling, N. A., Merkouris, S. S., Greenwood, C. J., Oldenhof, E., Toumbourou, J. W., and Youssef, G. J. (2017). Early risk and protective factors for problem gambling: a systematic review and meta-analysis of longitudinal studies. Clin. Psychol. Rev . 51, 109–124. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2016.10.008

Edgren, R., Castrén, S., Mäkelä, M., Pörtfors, P., Alho, H., and Salonen, A. H. (2016). Reliability of instruments measuring at-risk and problem gambling among young individuals: a systematic review covering years 2009-2015. J. Adolesc. Health 58, 600–615. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2016.03.007

Pickering, D., Keen, B., Entwistle, G., and Blaszczynski, A. (2018). Measuring treatment outcomes in gambling disorders: a systematic review. Addiction 113, 411–426. doi: 10.1111/add.13968

Shaffer, H. J., Stanton, M. V., and Nelson, S. E. (2006). Trends in gambling studies research: quantifying, categorizing, and describing citations. J. Gambl. Stud . 22, 427–442. doi: 10.1007/s10899-006-9023-7

Keywords: gambling, problem gambling, adolescence, measurement, risk factors, prevention, treatment

Citation: Hayer T, Primi C, Ricijas N, Olason DT and Derevensky JL (2018) Editorial: Problem Gambling: Summarizing Research Findings and Defining New Horizons. Front. Psychol . 9:1670. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2018.01670

Received: 13 August 2018; Accepted: 20 August 2018; Published: 06 September 2018.

Copyright © 2018 Hayer, Primi, Ricijas, Olason and Derevensky. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY) . The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Tobias Hayer, [email protected]

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

- Research article

- Open access

- Published: 22 August 2017

Why do young adults gamble online? A qualitative study of motivations to transition from social casino games to online gambling

- Hyoun S. Kim 1 ,

- Michael J. A. Wohl 2 ,

- Rina Gupta 3 &

- Jeffrey L. Derevensky 4

Asian Journal of Gambling Issues and Public Health volume 7 , Article number: 6 ( 2017 ) Cite this article

25k Accesses

23 Citations

2 Altmetric

Metrics details

The present research examined the mechanisms of initiating online gambling among young adults. Of particular interest was whether social casino gaming was noted as part of young adults’ experience with online gambling. This is because there is growing concern that social casino gaming may be a ‘gateway’ to online gambling. Three focus groups ( N = 21) were conducted with young adult online gamblers from two large Canadian Universities. Participants noted the role of peer influence as well as incentives (e.g., sign up bonuses) as important factors that motivated them to start engaging in online gambling. Participants also noted a link between social casino games and online gambling. Specifically, several young adults reported migrating to online gambling within a relatively short period after engaging with social casino games. Potential mechanisms that may lead to the migration from social casino games to online gambling included the role of advertisements and the inflated pay out rates on these free to play gambling like games. The results suggest initiatives to prevent the development of disordered gambling should understand the potential of social casino gaming to act as a gateway to online gambling, especially amongst this vulnerable population.

Over the past decade, the use of computers and the Internet has significantly altered the gambling landscape. The gambling industry is no longer bound by brick and mortar gambling venues (e.g., casinos, racetracks). Today, access to gambling activities can be achieved with a few keystrokes on a computer. One point of access that has gained increased attention from researchers in the field of gambling studies is social media sites such as Facebook (Wohl et al. 2017 ). In part, this increased attention is because social media sites have become a popular platform for people to access online gambling venues via hyperlinks embedded in advertisements (Abarbanel et al. 2016 ). Social media sites also allow users to engage in free-to-play simulated gambling games through applications. These free-to-play simulated gambling games have become referred to as social casino games (Gainsbury et al. 2014 ). There is evidence to suggest, however, that social casino game play may act as a ‘gateway’ to gambling for real money (for a review see Wohl et al. 2017 ).

The current research took a qualitative approach to assess young adult online gamblers experiences with online gambling to determine the process and mechanisms that may lead young adults to gamble online, including the role of social casino games. In other words, the present research aimed to examine the motivations for gambling online, including transitioning from social casino games to online gambling. A focus was placed on young adults’ experience with online gambling due to their propensity to gamble online (McBride and Derevensky 2009 ), play social casino games (Derevensky and Gainsbury 2016 ), as well as their elevated rates of disordered gambling (Welte et al. 2011 ). Further, social casino games were the focus as there is a current need to understand the issues regarding the gaming-social media crossover.