Formal Operational Stage – Piaget’s 4th Stage (Examples)

Would you say that you think abstractly? Do you think about the “bigger picture?” I don’t mean thinking about your life 10 years in the future. I mean thinking about the purpose of existence and why humans have evolved as we have. We’re not tackling all of these questions today, but we will talk about how we came to ask them and how we answer them.

Children in elementary or middle school typically do not possess these skills. Until children reach the formal operational stage in Jean Piaget's Theory of Cognitive Development, they go through three concrete development stages that only allow them to think concretely. They can follow the rules of how the world works but are limited by these concrete concepts.

What Is the Formal Operational Stage?

Once children reach adolescence, they enter the Formal Operational Stage. This is the last stage in Piaget’s Theory of Cognitive Development. The Formal Operational Stage doesn’t end - there are ways that you can heighten your abstract problem-solving skills from age 12 to age 112!

The formal operational stage begins between around 11-12. Children are usually in grade school around this time. They can take on more responsibilities than they did in earlier stages of development, but they are still considered young children. Health organizations still categorize ages 11 and 12 as "middle childhood."

Entering the Formal Operational Stage

Children ages 11 and 12 have just finished the concrete operational stage. This stage lasts from ages 6-11. By the time a child enters the formal operational stage, they should be able to:

- Arrange items in a logical order

- Build friendships based on empathy

- Understand that 5mL of water in one glass is the same amount as 5mL of water in a separate glass

- Recognize that a ball of pizza dough is the same as flattened pizza dough

Playing games and doing science experiments with children is much more fun at this age. They understand so much more!

During this stage, individuals develop the ability to think abstractly, reason logically, and solve problems in a systematic manner. Here are 14 examples of behaviors and thought processes that are characteristic of the formal operational stage:

- Hypothetical Thinking : The ability to consider hypothetical situations and possibilities. For instance, a teenager might ponder, "What would happen if the sun never rose?"

- Abstract Thought : Thinking about concepts not directly tied to concrete experiences, such as justice, love, or morality.

- Systematic Problem Solving : When faced with a problem, individuals can systematically test potential solutions. For example, if a science experiment doesn't produce the expected result, a student might change one variable at a time to determine which one is responsible.

- Metacognition : The ability to think about one's own thought processes. Students might reflect on how they study best or recognize when they do not understand a concept.

- Moral Reasoning : Moving beyond black-and-white thinking to consider the nuances of moral dilemmas. For instance, understanding that stealing is generally wrong but pondering whether it's justified if someone is stealing food to feed their starving family.

- Scientific Reasoning : Formulating hypotheses and conducting experiments in a methodical manner to test them.

- Understanding Sarcasm and Metaphors : Recognizing that the phrase "It's raining cats and dogs" doesn't mean animals are falling from the sky.

- Planning for the Future : Considering future possibilities and making plans based on them, such as choosing college courses based on a desired future career.

- Evaluating the Quality of Information : Recognizing the difference between opinion and fact or understanding that just because something is on the internet doesn't make it true.

- Logical Thought : Thinking logically and methodically, even about abstract concepts. For example, if all roses are flowers and some flowers fade quickly, then some roses fade quickly.

- Considering Multiple Perspectives : Understanding that others might have a different point of view and trying to see things from their perspective.

- Propositional Thought : Understanding that a statement can be logical based solely on the information provided, even if it's untrue. For instance, "If all dogs can fly and Fido is a dog, then Fido can fly" is logically sound, even though we know dogs can't fly.

- Complex Classification : Classifying objects based on multiple characteristics. For example, organizing books by both genre and author.

- Understanding Abstract Relationships : Recognizing relationships like "If A is greater than B, and B is greater than C, then A is greater than C."

What Characterizes the Formal Operational Stage?

Four specific skills are signs that a child is in the formal operational stage:

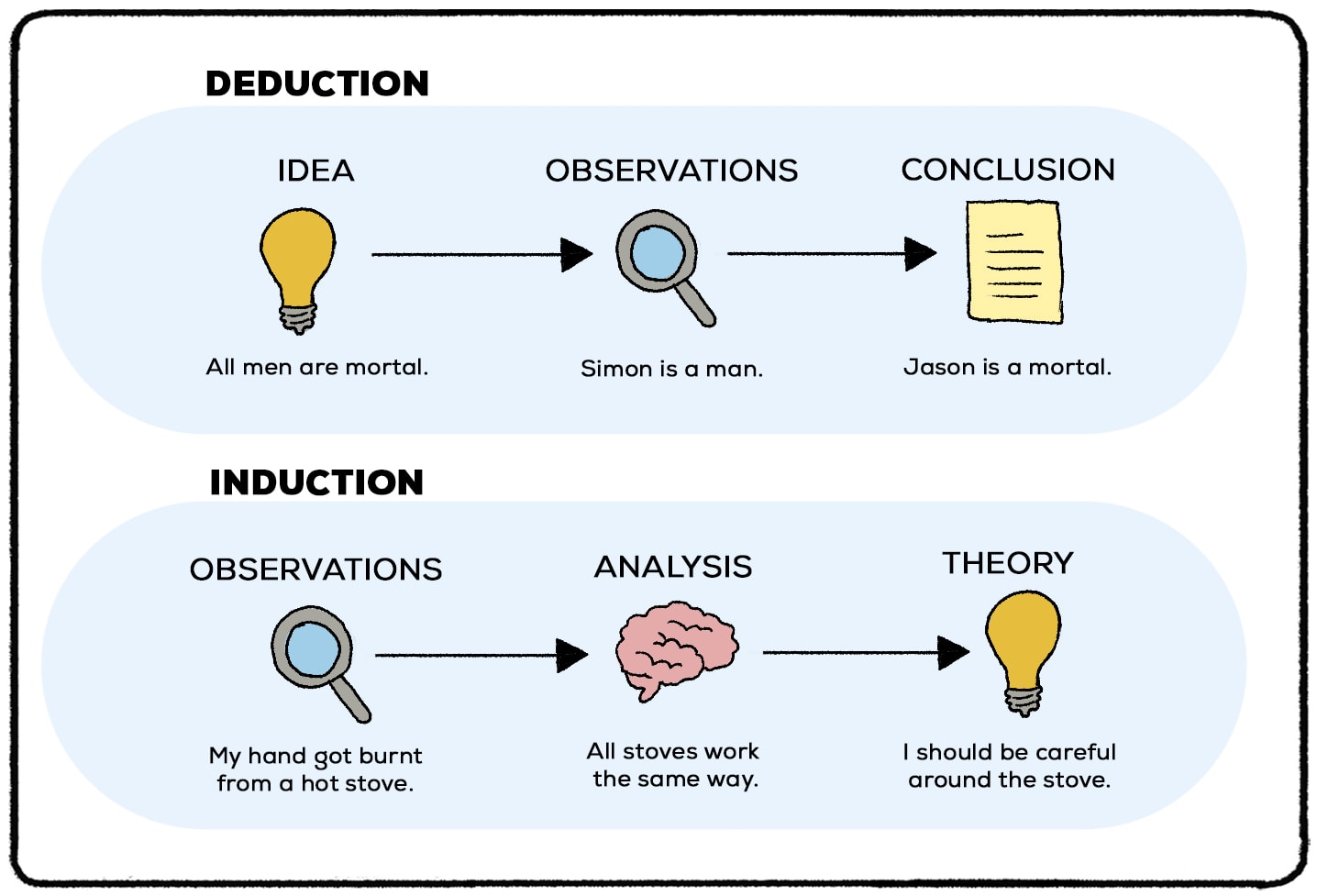

Deductive Reasoning

Abstract thought, problem-solving.

- Metacognition

The child learns to apply logic to certain situations during the Concrete Operational Stage . But they are limited to inductive reasoning. In the Formal Operational Stage, they start to learn (and learn the limits of) deductive reasoning.

Inductive reasoning uses observations to make a conclusion. Say a student has six teachers throughout their life, all strict. They are likely to conclude that all teachers are strict. They may find that later in life, they will change their conclusion, but until they observe a teacher who is not strict, this is the conclusion they will come to.

Deductive reasoning works differently. It uses facts and lessons to create a conclusion. The child will be presented with two facts:

“All teachers are strict.”

“Mr. Johnson is a teacher.”

Using deductive reasoning, the child can conclude that Mr. Johnson is strict.

Throughout the child’s development, they start to expand their world. In the sensorimotor stage, their world consists of only what is directly in front of them. If something is out of sight or earshot, it no longer exists.

As they develop object permanence, they understand that the world exists beyond what they can physically see, hear, or touch. In the concrete operational stage, children begin to apply the rules of logic to things and rules they know exist.

In this final stage, they begin to expand their worldview further. They begin to develop abstract thought. They can apply logic to situations that don’t follow the rules of the physical world.

Piaget's Third Eye Question: The Difference Between Concrete Operational and Formal Operational Stages

One of the ways that Piaget tested this skill was to ask the children questions. Here’s an example of a question that Piaget asked children:

“If you had a third eye, where would you put it?”

Children in the Concrete Operational Stage were limited to answering that they would put the eye on their forehead or face. They were typically only exposed to animals and humans with eyes on their faces. But children in the Formal Operational Stage were likelier to branch out and think of more useful and abstract answers. They considered putting the eye on their hand, back, or elsewhere where it would serve a greater purpose.

These skills make solving problems a whole lot easier. Children can only solve problems through trial and error in the Concrete Operational Stage and earlier stages. As they enter the Formal Operational Stage, they can look back at the problem, use past experience and reasoning to form a hypothesis, and test out what they believe will happen. This can save them a lot of time.

To determine when children had developed these skills, Piaget used another testing method. He gave them a scale with a set of weights and asked them to balance the scale with the weights. But simply putting the same amount of weight on each side wasn’t enough. The children had to determine that the distance between the weights and the scale's center also impacted the balance.

Children under the age of 10 heavily struggled with the task because they could not understand the concept of balance (if they were in the Preoperational Stage) or could not grasp that the center of balance is also important. (These children were in the early stages of the Concrete Operational Stage.) At age 10, the children could solve the problem, but at a much slower pace due to their process of trial and error.

It wasn’t until age 11 or 12 that children could look at the problem from a distance and use logic to use both the distance and size of the weights to balance the scale.

MetaCognition

Not all of these thought processes are perfect the first time around. You know that I know that, and children in the Formal Operational Stage are just starting to discover that. By using MetaCognition, they are more likely to assess their thinking and transform it into a more effective form of problem-solving.

MetaCognition is simply “thinking about thinking.” It is the ability to run through your own thought process, figure out how you developed that process, and maybe unwind some things that aren’t logical or can be disproven. This can help you “rebuild” your thought process as if it were building blocks, creating a more solid structure for you to solve problems.

Piaget did not actually coin this term while developing his theory on the Formal Operational Stage. John Flavell, an American psychologist, actually proposed the theory on MetaCognition in the late 1970s.

We’ve seen throughout these videos that the Theory of Cognitive Development has continued to grow and change with additional input and studies. Our minds can also change their thought processes and begin to notice imperfections and flawed logic as they come up. But this often requires going back and asking yourself how you built certain thought processes and where you could have made flawed conclusions.

How to Support a Child in the Formal Operational Stage

Children in the formal operational stage (typically 12 years and older) begin thinking more abstractly and logically, engaging in hypothetical reasoning and considering multiple variables in problem-solving. To best support and nurture their cognitive development outside of school, consider these activity suggestions:

- Play Strategic Board Games: Introduce games that require planning, strategizing, and critical thinking. Games like chess, Risk, Settlers of Catan, and Ticket to Ride can enhance their deductive reasoning and promote patience. These games also often require players to predict opponents' moves, honing their skills in understanding perspectives.

- Engage in Thought Experiments: Stimulate abstract thinking by posing hypothetical questions. Asking imaginative yet thought-provoking questions like, "If you could invent a new school subject, what would it be and why?" or "How would our lives change if we had no electricity for a year?" can spark interesting discussions and foster creativity.

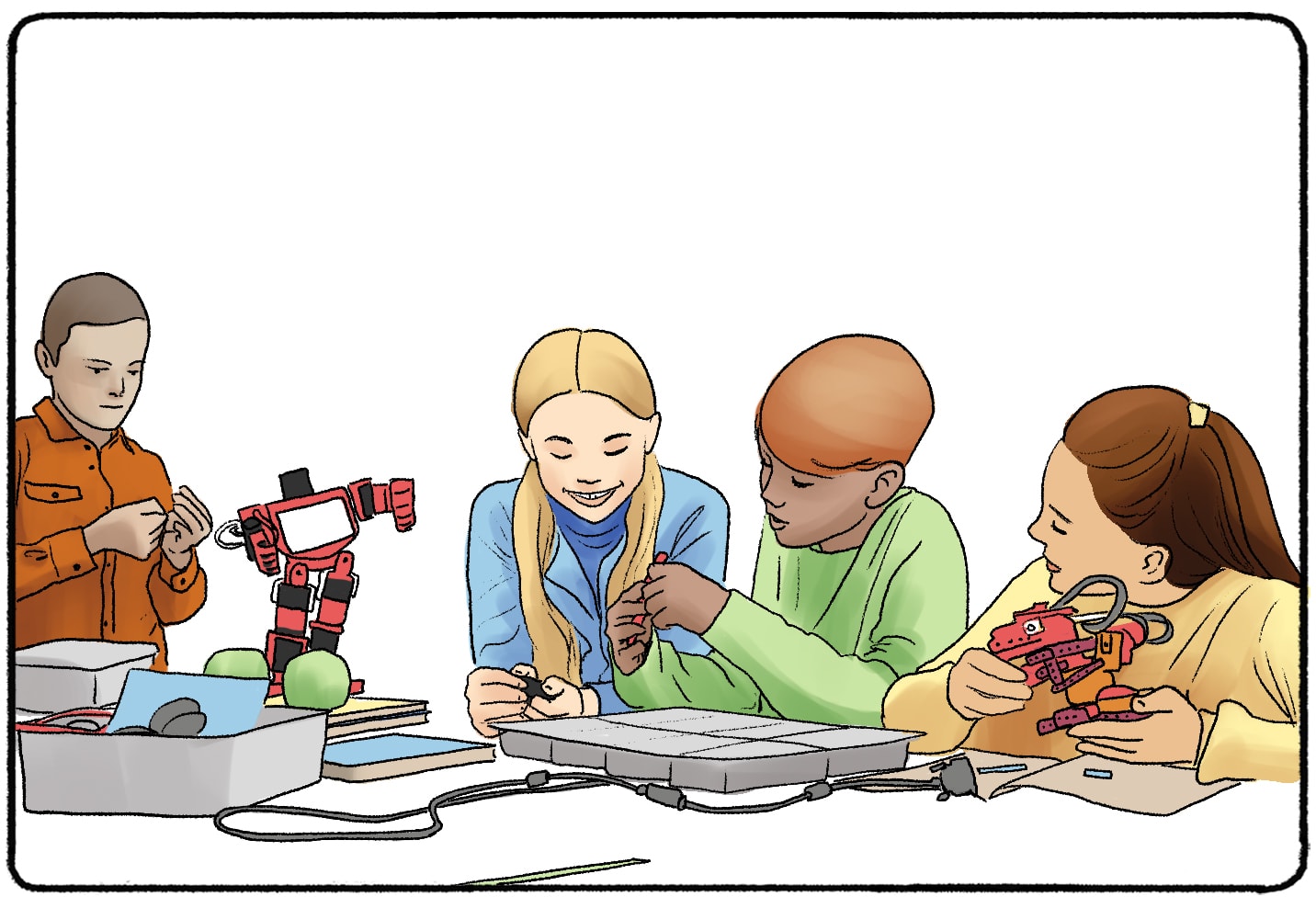

- Encourage Scientific Experiments: Let them set up a mini-lab at home. Whether it's a simple vinegar and baking soda reaction or a more complex examination of plant growth under different conditions, hands-on experiments can solidify their understanding of cause and effect.

- Delve into Philosophy and Ethics: Discuss moral dilemmas or philosophical conundrums suitable for their age. Questions like, "Is it ever okay to lie?" or "What makes something 'right' or 'wrong'?" can challenge them to consider multiple viewpoints and refine their moral reasoning.

- Read and Analyze Stories Together: Choose books or movies with deeper themes or complex characters. Discuss the motives, the plot's implications, or any symbolism. This improves their comprehension skills and teaches them to think critically about media.

- Involve Them in Real-Life Problem-Solving: Whether planning a family trip, budgeting for a big purchase, or deciding on the best route for a journey, including them in the process can provide practical applications for their developing logical reasoning skills.

- Respect and Respond to Their Queries: Children at this stage are brimming with questions, many of which can be profound or reflective. When they approach you with a query, respond with patience and logic. If you don't know the answer, consider researching it together. This collaborative approach provides them with information and models a proactive attitude toward learning.

By actively engaging with children in these ways, parents and caregivers can provide invaluable support as they navigate the challenges and opportunities of the formal operational stage.

Formal Operational Stage vs. Other Stages of Development

Jean Piaget is not the only psychologist to create stages of development. Other psychologists have offered their theories on how a child develops social skills and how their experiences during each stage impact their relationships and behavior. Some theories, like Erikson's stages of psychosocial development, last for the span of the person's life. Other theories, like Piaget's, only cover childhood and early adolescence. When we compare Piaget's theory to other theories, we see some overlap and other perspectives on what makes a child the person they grow up to be.

Erikson's Stages of Psychosocial Development

At ages 11-12, a child exits the Industry vs. Inferiority stage and enters the Identity vs. Role Confusion stage. The child should be aware that they are responsible for their own decisions and how they affect others. They also start to see that they are different from other children. They will successfully exit these stages if they feel confident that they can advocate for themselves and live the way they want. Otherwise, they may develop insecurities. Erikson coined the term "identity crisis." This crisis could take place in the identity vs. role confusion stage!

Freud's Stages of Psychosexual Development

During the ages of 11-12, a child is in the latent stage of psychosexual development and may be entering the genital stage. The change in stages all depends on when the child goes through puberty. Freud's controversial stages focused on a child's erogenous zones and sexual interests. As the child discovers sexual interests in the latent stage, they must learn to channel their energy into intellectual activities. The child can form healthy relationships by letting the superego tame the id. In the genital stage, teenagers and adults learn to explore their maturing sexual interests.

Which Theory is "Right?"

All these theories can play out simultaneously, but remember, these are just theories. Some ideas, like Freud's Oedipal Complex that occurred in earlier stages of development, have been discredited and largely rejected by today's psychologists. We continue to learn about Jean Piaget, Erik Erikson, and other psychologists to understand how psychology developed into the field we know today.

Thanks for checking out these pages on the Theory of Cognitive Development! I hope these will allow you to look at your own thinking and build a stronger foundation for solving problems and understanding the world around you - no matter how old you are!

Piaget's Influence on Modern Educational Practices

Jean Piaget's groundbreaking theories on cognitive development have left an indelible mark on the realm of education. Even today, educators worldwide employ strategies rooted in Piaget's insights. Here's how Piaget’s theories continue to shape contemporary educational practices:

- Active Learning: Piaget emphasized the importance of active learning. He believed children learn best when interacting with their environment and manipulating objects. This belief has shifted from passive rote memorization to hands-on, experiential learning. Schools often incorporate field trips, lab experiments, and interactive activities to facilitate this.

- Developmentally Appropriate Practices: Recognizing that children progress through specific stages of cognitive development, educators design curricula tailored to these stages. For instance, in the pre-operational stage (2-7 years), children benefit from using concrete objects and visuals. Meanwhile, older children in the formal operational stage (12 years and up) are more equipped for abstract thinking and can engage in more complex problem-solving tasks.

- Focus on the Process, Not Just the Outcome: Piaget believed that the process of thinking and the journey of arriving at an answer are just as necessary as the answer itself. This philosophy has encouraged educators to value and assess how students approach problems, not just the correctness of their answers.

- Peer Interaction: Piaget felt that peer interaction is crucial for cognitive development. He observed that children often learn best when discussing, debating, and collaborating with classmates. Group work, cooperative learning, and classroom discussions are now staples in many classrooms, promoting social interaction as a valuable learning tool.

- Incorporating Real-life Situations: To make learning meaningful, Piaget suggested relating it to real-life situations. This has led to problem-based learning and the inclusion of real-world issues in the curriculum, ensuring that students see the relevance and applicability of their learning.

- Role of the Teacher: In line with Piaget's theories, the teacher's role has evolved from the traditional "sage on the stage" to more of a "guide on the side." Teachers now often act as facilitators, providing resources, posing guiding questions, and helping students make their discoveries.

- Assessment Practices: Piaget's emphasis on stages of cognitive development has led to more nuanced and stage-sensitive assessment methods. Teachers are more attuned to the developmental readiness of their students, ensuring that assessments are appropriate for their cognitive level.

- Constructivist Classrooms: Stemming from Piaget's idea that learners construct knowledge based on their experiences, many modern classrooms adopt a constructivist approach. Here, students are encouraged to construct their understanding and knowledge of the world by experiencing and reflecting on those experiences.

While educational practices have evolved and integrated various theories, Piaget's influence is unmistakably prevalent. His focus on the child as an active learner, the stages of cognitive development, and the significance of hands-on, relevant learning continues to shape how education is delivered in the 21st century.

Related posts:

- Concrete Operational Stage (3rd Cognitive Development)

- Piaget's Theory of Moral Development (4 Stages + Examples)

- Jean Piaget’s Theory of Cognitive Development

- Havighurst’s Developmental Task Theory

- The Psychology of Long Distance Relationships

Reference this article:

About The Author

Developmental Psychology:

Developmental Psychology

Erikson's Psychosocial Stages

Trust vs Mistrust

Autonomy vs Shame

Initiative vs Guilt

Industry vs inferiority

Identity vs Confusion

Intimacy vs Isolation

Generativity vs Stagnation

Integrity vs Despair

Attachment Styles

Avoidant Attachment

Anxious Attachment

Secure Attachment

Lawrence Kohlberg's Stages of Moral Development

Piaget's Cognitive Development

Sensorimotor Stage

Object Permanence

Preoperational Stage

Concrete Operational Stage

Formal Operational Stage

Unconditional Positive Regard

Birth Order

Zone of Proximal Development

PracticalPie.com is a participant in the Amazon Associates Program. As an Amazon Associate we earn from qualifying purchases.

Follow Us On:

Youtube Facebook Instagram X/Twitter

Psychology Resources

Developmental

Personality

Relationships

Psychologists

Serial Killers

Psychology Tests

Personality Quiz

Memory Test

Depression test

Type A/B Personality Test

© PracticalPsychology. All rights reserved

Privacy Policy | Terms of Use

Piaget’s Theory and Stages of Cognitive Development

Saul Mcleod, PhD

Editor-in-Chief for Simply Psychology

BSc (Hons) Psychology, MRes, PhD, University of Manchester

Saul Mcleod, PhD., is a qualified psychology teacher with over 18 years of experience in further and higher education. He has been published in peer-reviewed journals, including the Journal of Clinical Psychology.

Learn about our Editorial Process

Olivia Guy-Evans, MSc

Associate Editor for Simply Psychology

BSc (Hons) Psychology, MSc Psychology of Education

Olivia Guy-Evans is a writer and associate editor for Simply Psychology. She has previously worked in healthcare and educational sectors.

On This Page:

Key Takeaways

- Jean Piaget is famous for his theories regarding changes in cognitive development that occur as we move from infancy to adulthood.

- Cognitive development results from the interplay between innate capabilities (nature) and environmental influences (nurture).

- Children progress through four distinct stages , each representing varying cognitive abilities and world comprehension: the sensorimotor stage (birth to 2 years), the preoperational stage (2 to 7 years), the concrete operational stage (7 to 11 years), and the formal operational stage (11 years and beyond).

- A child’s cognitive development is not just about acquiring knowledge, the child has to develop or construct a mental model of the world, which is referred to as a schema .

- Piaget emphasized the role of active exploration and interaction with the environment in shaping cognitive development, highlighting the importance of assimilation and accommodation in constructing mental schemas.

Stages of Development

Jean Piaget’s theory of cognitive development suggests that children move through four different stages of intellectual development which reflect the increasing sophistication of children’s thought

Each child goes through the stages in the same order (but not all at the same rate), and child development is determined by biological maturation and interaction with the environment.

At each stage of development, the child’s thinking is qualitatively different from the other stages, that is, each stage involves a different type of intelligence.

Although no stage can be missed out, there are individual differences in the rate at which children progress through stages, and some individuals may never attain the later stages.

Piaget did not claim that a particular stage was reached at a certain age – although descriptions of the stages often include an indication of the age at which the average child would reach each stage.

The Sensorimotor Stage

Ages: Birth to 2 Years

The first stage is the sensorimotor stage , during which the infant focuses on physical sensations and learning to coordinate its body.

Major Characteristics and Developmental Changes:

- The infant learns about the world through their senses and through their actions (moving around and exploring their environment).

- During the sensorimotor stage, a range of cognitive abilities develop. These include: object permanence; self-recognition (the child realizes that other people are separate from them); deferred imitation; and representational play.

- They relate to the emergence of the general symbolic function, which is the capacity to represent the world mentally

- At about 8 months, the infant will understand the permanence of objects and that they will still exist even if they can’t see them and the infant will search for them when they disappear.

During the beginning of this stage, the infant lives in the present. It does not yet have a mental picture of the world stored in its memory therefore it does not have a sense of object permanence.

If it cannot see something, then it does not exist. This is why you can hide a toy from an infant, while it watches, but it will not search for the object once it has gone out of sight.

The main achievement during this stage is object permanence – knowing that an object still exists, even if it is hidden. It requires the ability to form a mental representation (i.e., a schema) of the object.

Towards the end of this stage the general symbolic function begins to appear where children show in their play that they can use one object to stand for another. Language starts to appear because they realise that words can be used to represent objects and feelings.

The child begins to be able to store information that it knows about the world, recall it, and label it.

Individual Differences

- Cultural Practices : In some cultures, babies are carried on their mothers’ backs throughout the day. This constant physical contact and varied stimuli can influence how a child perceives their environment and their sense of object permanence.

- Gender Norms : Toys assigned to babies can differ based on gender expectations. A boy might be given more cars or action figures, while a girl might receive dolls or kitchen sets. This can influence early interactions and sensory explorations.

Learn More: The Sensorimotor Stage of Cognitive Development

The Preoperational Stage

Ages: 2 – 7 Years

Piaget’s second stage of intellectual development is the preoperational stage . It takes place between 2 and 7 years. At the beginning of this stage, the child does not use operations, so the thinking is influenced by the way things appear rather than logical reasoning.

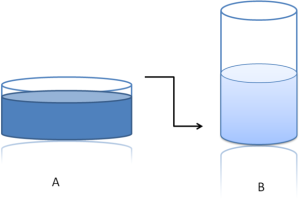

A child cannot conserve which means that the child does not understand that quantity remains the same even if the appearance changes.

Furthermore, the child is egocentric; he assumes that other people see the world as he does. This has been shown in the three mountains study.

As the preoperational stage develops, egocentrism declines, and children begin to enjoy the participation of another child in their games, and let’s pretend play becomes more important.

Toddlers often pretend to be people they are not (e.g. superheroes, policemen), and may play these roles with props that symbolize real-life objects. Children may also invent an imaginary playmate.

- Toddlers and young children acquire the ability to internally represent the world through language and mental imagery.

- During this stage, young children can think about things symbolically. This is the ability to make one thing, such as a word or an object, stand for something other than itself.

- A child’s thinking is dominated by how the world looks, not how the world is. It is not yet capable of logical (problem-solving) type of thought.

- Moreover, the child has difficulties with class inclusion; he can classify objects but cannot include objects in sub-sets, which involves classifying objects as belonging to two or more categories simultaneously.

- Infants at this stage also demonstrate animism. This is the tendency for the child to think that non-living objects (such as toys) have life and feelings like a person’s.

By 2 years, children have made some progress toward detaching their thoughts from the physical world. However, have not yet developed logical (or “operational”) thought characteristics of later stages.

Thinking is still intuitive (based on subjective judgments about situations) and egocentric (centered on the child’s own view of the world).

- Cultural Storytelling : Different cultures have unique stories, myths, and folklore. Children from diverse backgrounds might understand and interpret symbolic elements differently based on their cultural narratives.

- Race & Representation : A child’s racial identity can influence how they engage in pretend play. For instance, a lack of diverse representation in media and toys might lead children of color to recreate scenarios that don’t reflect their experiences or background.

Learn More: The Preoperational Stage of Cognitive Development

The Concrete Operational Stage

Ages: 7 – 11 Years

By the beginning of the concrete operational stage , the child can use operations (a set of logical rules) so they can conserve quantities, realize that people see the world in a different way (decentring), and demonstrate improvement in inclusion tasks. Children still have difficulties with abstract thinking.

- During this stage, children begin to think logically about concrete events.

- Children begin to understand the concept of conservation; understanding that, although things may change in appearance, certain properties remain the same.

- During this stage, children can mentally reverse things (e.g., picture a ball of plasticine returning to its original shape).

- During this stage, children also become less egocentric and begin to think about how other people might think and feel.

The stage is called concrete because children can think logically much more successfully if they can manipulate real (concrete) materials or pictures of them.

Piaget considered the concrete stage a major turning point in the child’s cognitive development because it marks the beginning of logical or operational thought. This means the child can work things out internally in their head (rather than physically try things out in the real world).

Children can conserve number (age 6), mass (age 7), and weight (age 9). Conservation is the understanding that something stays the same in quantity even though its appearance changes.

But operational thought is only effective here if the child is asked to reason about materials that are physically present. Children at this stage will tend to make mistakes or be overwhelmed when asked to reason about abstract or hypothetical problems.

- Cultural Context in Conservation Tasks : In a society where resources are scarce, children might demonstrate conservation skills earlier due to the cultural emphasis on preserving and reusing materials.

- Gender & Learning : Stereotypes about gender abilities, like “boys are better at math,” can influence how children approach logical problems or classify objects based on perceived gender norms.

Learn More: The Concrete Operational Stage of Development

The Formal Operational Stage

Ages: 12 and Over

The formal operational period begins at about age 11. As adolescents enter this stage, they gain the ability to think in an abstract manner, the ability to combine and classify items in a more sophisticated way, and the capacity for higher-order reasoning.

Adolescents can think systematically and reason about what might be as well as what is (not everyone achieves this stage). This allows them to understand politics, ethics, and science fiction, as well as to engage in scientific reasoning.

Adolescents can deal with abstract ideas: e.g. they can understand division and fractions without having to actually divide things up, and solve hypothetical (imaginary) problems.

- Concrete operations are carried out on things whereas formal operations are carried out on ideas. Formal operational thought is entirely freed from physical and perceptual constraints.

- During this stage, adolescents can deal with abstract ideas (e.g. no longer needing to think about slicing up cakes or sharing sweets to understand division and fractions).

- They can follow the form of an argument without having to think in terms of specific examples.

- Adolescents can deal with hypothetical problems with many possible solutions. E.g. if asked ‘What would happen if money were abolished in one hour’s time? they could speculate about many possible consequences.

From about 12 years children can follow the form of a logical argument without reference to its content. During this time, people develop the ability to think about abstract concepts, and logically test hypotheses.

This stage sees the emergence of scientific thinking, formulating abstract theories and hypotheses when faced with a problem.

- Culture & Abstract Thinking : Cultures emphasize different kinds of logical or abstract thinking. For example, in societies with a strong oral tradition, the ability to hold complex narratives might develop prominently.

- Gender & Ethics : Discussions about morality and ethics can be influenced by gender norms. For instance, in some cultures, girls might be encouraged to prioritize community harmony, while boys might be encouraged to prioritize individual rights.

Learn More: The Formal Operational Stage of Development

Piaget’s Theory

- Piaget’s theory places a strong emphasis on the active role that children play in their own cognitive development.

- According to Piaget, children are not passive recipients of information; instead, they actively explore and interact with their surroundings.

- This active engagement with the environment is crucial because it allows them to gradually build their understanding of the world.

1. How Piaget Developed the Theory

Piaget was employed at the Binet Institute in the 1920s, where his job was to develop French versions of questions on English intelligence tests. He became intrigued with the reasons children gave for their wrong answers to the questions that required logical thinking.

He believed that these incorrect answers revealed important differences between the thinking of adults and children.

Piaget branched out on his own with a new set of assumptions about children’s intelligence:

- Children’s intelligence differs from an adult’s in quality rather than in quantity. This means that children reason (think) differently from adults and see the world in different ways.

- Children actively build up their knowledge about the world . They are not passive creatures waiting for someone to fill their heads with knowledge.

- The best way to understand children’s reasoning is to see things from their point of view.

Piaget did not want to measure how well children could count, spell or solve problems as a way of grading their I.Q. What he was more interested in was the way in which fundamental concepts like the very idea of number , time, quantity, causality , justice , and so on emerged.

Piaget studied children from infancy to adolescence using naturalistic observation of his own three babies and sometimes controlled observation too. From these, he wrote diary descriptions charting their development.

He also used clinical interviews and observations of older children who were able to understand questions and hold conversations.

2. Piaget’s Theory Differs From Others In Several Ways:

Piaget’s (1936, 1950) theory of cognitive development explains how a child constructs a mental model of the world. He disagreed with the idea that intelligence was a fixed trait, and regarded cognitive development as a process that occurs due to biological maturation and interaction with the environment.

Children’s ability to understand, think about, and solve problems in the world develops in a stop-start, discontinuous manner (rather than gradual changes over time).

- It is concerned with children, rather than all learners.

- It focuses on development, rather than learning per se, so it does not address learning of information or specific behaviors.

- It proposes discrete stages of development, marked by qualitative differences, rather than a gradual increase in number and complexity of behaviors, concepts, ideas, etc.

The goal of the theory is to explain the mechanisms and processes by which the infant, and then the child, develops into an individual who can reason and think using hypotheses.

To Piaget, cognitive development was a progressive reorganization of mental processes as a result of biological maturation and environmental experience.

Children construct an understanding of the world around them, then experience discrepancies between what they already know and what they discover in their environment.

Piaget claimed that knowledge cannot simply emerge from sensory experience; some initial structure is necessary to make sense of the world.

According to Piaget, children are born with a very basic mental structure (genetically inherited and evolved) on which all subsequent learning and knowledge are based.

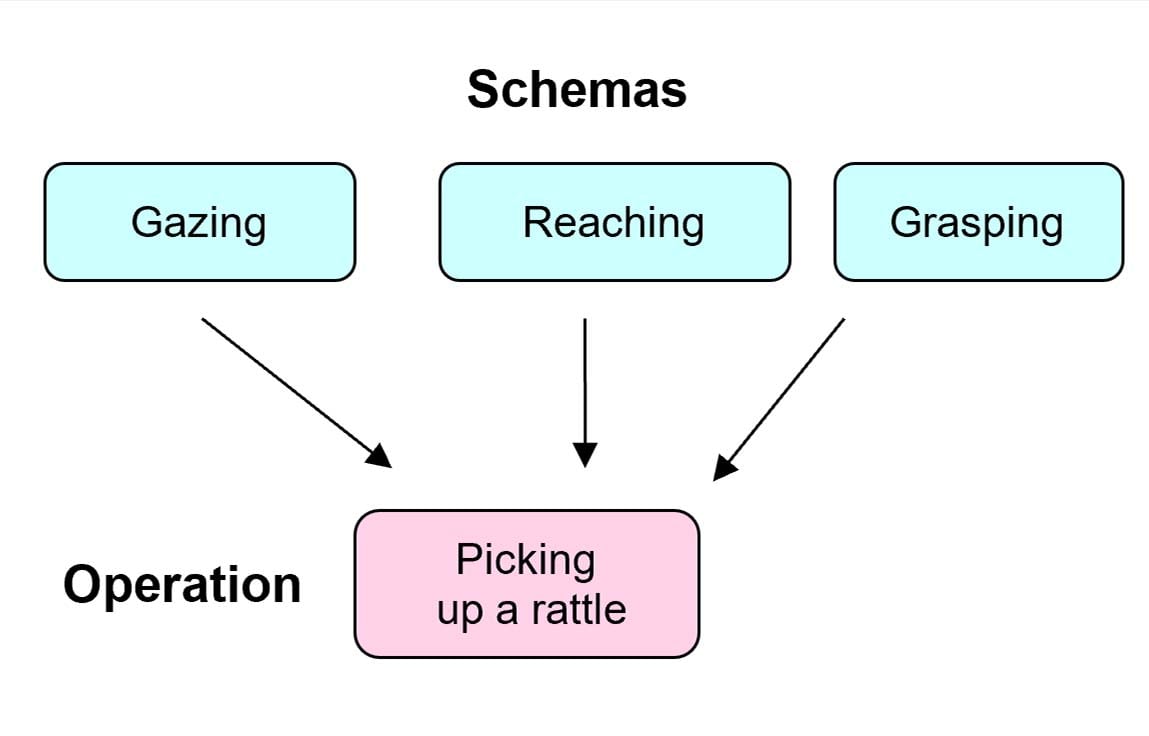

Schemas are the basic building blocks of such cognitive models, and enable us to form a mental representation of the world.

Piaget (1952, p. 7) defined a schema as: “a cohesive, repeatable action sequence possessing component actions that are tightly interconnected and governed by a core meaning.”

In more simple terms, Piaget called the schema the basic building block of intelligent behavior – a way of organizing knowledge. Indeed, it is useful to think of schemas as “units” of knowledge, each relating to one aspect of the world, including objects, actions, and abstract (i.e., theoretical) concepts.

Wadsworth (2004) suggests that schemata (the plural of schema) be thought of as “index cards” filed in the brain, each one telling an individual how to react to incoming stimuli or information.

When Piaget talked about the development of a person’s mental processes, he was referring to increases in the number and complexity of the schemata that a person had learned.

When a child’s existing schemas are capable of explaining what it can perceive around it, it is said to be in a state of equilibrium, i.e., a state of cognitive (i.e., mental) balance.

Operations are more sophisticated mental structures which allow us to combine schemas in a logical (reasonable) way.

As children grow they can carry out more complex operations and begin to imagine hypothetical (imaginary) situations.

Apart from the schemas we are born with schemas and operations are learned through interaction with other people and the environment.

Piaget emphasized the importance of schemas in cognitive development and described how they were developed or acquired.

A schema can be defined as a set of linked mental representations of the world, which we use both to understand and to respond to situations. The assumption is that we store these mental representations and apply them when needed.

Examples of Schemas

A person might have a schema about buying a meal in a restaurant. The schema is a stored form of the pattern of behavior which includes looking at a menu, ordering food, eating it and paying the bill.

This is an example of a schema called a “script.” Whenever they are in a restaurant, they retrieve this schema from memory and apply it to the situation.

The schemas Piaget described tend to be simpler than this – especially those used by infants. He described how – as a child gets older – his or her schemas become more numerous and elaborate.

Piaget believed that newborn babies have a small number of innate schemas – even before they have had many opportunities to experience the world. These neonatal schemas are the cognitive structures underlying innate reflexes. These reflexes are genetically programmed into us.

For example, babies have a sucking reflex, which is triggered by something touching the baby’s lips. A baby will suck a nipple, a comforter (dummy), or a person’s finger. Piaget, therefore, assumed that the baby has a “sucking schema.”

Similarly, the grasping reflex which is elicited when something touches the palm of a baby’s hand, or the rooting reflex, in which a baby will turn its head towards something which touches its cheek, are innate schemas. Shaking a rattle would be the combination of two schemas, grasping and shaking.

4. The Process of Adaptation

Piaget also believed that a child developed as a result of two different influences: maturation, and interaction with the environment. The child develops mental structures (schemata) which enables him to solve problems in the environment.

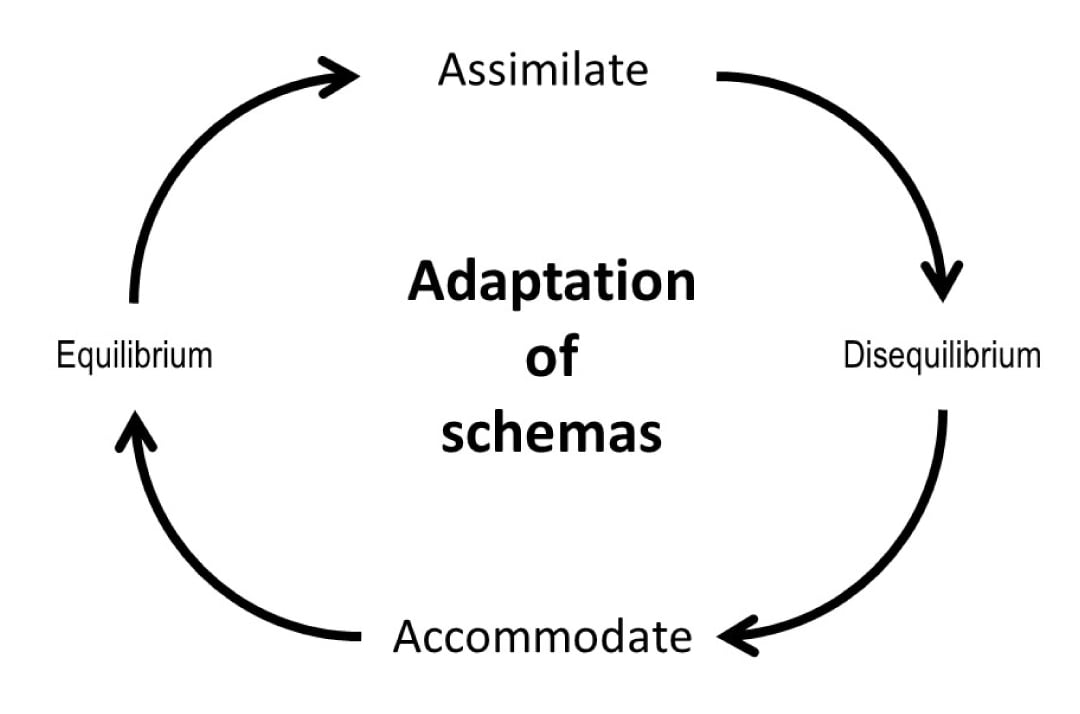

Adaptation is the process by which the child changes its mental models of the world to match more closely how the world actually is.

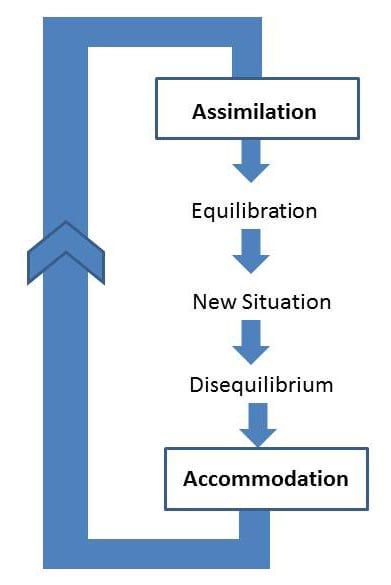

Adaptation is brought about by the processes of assimilation (solving new experiences using existing schemata) and accommodation (changing existing schemata in order to solve new experiences).

The importance of this viewpoint is that the child is seen as an active participant in its own development rather than a passive recipient of either biological influences (maturation) or environmental stimulation.

When our existing schemas can explain what we perceive around us, we are in a state of equilibration . However, when we meet a new situation that we cannot explain it creates disequilibrium, this is an unpleasant sensation which we try to escape, and this gives us the motivation to learn.

According to Piaget, reorganization to higher levels of thinking is not accomplished easily. The child must “rethink” his or her view of the world. An important step in the process is the experience of cognitive conflict.

In other words, the child becomes aware that he or she holds two contradictory views about a situation and they both cannot be true. This step is referred to as disequilibrium .

Jean Piaget (1952; see also Wadsworth, 2004) viewed intellectual growth as a process of adaptation (adjustment) to the world. This happens through assimilation, accommodation, and equilibration.

To get back to a state of equilibration, we need to modify our existing schemas to learn and adapt to the new situation.

This is done through the processes of accommodation and assimilation . This is how our schemas evolve and become more sophisticated. The processes of assimilation and accommodation are continuous and interactive.

5. Assimilation

Piaget defined assimilation as the cognitive process of fitting new information into existing cognitive schemas, perceptions, and understanding. Overall beliefs and understanding of the world do not change as a result of the new information.

Assimilation occurs when the new experience is not very different from previous experiences of a particular object or situation we assimilate the new situation by adding information to a previous schema.

This means that when you are faced with new information, you make sense of this information by referring to information you already have (information processed and learned previously) and trying to fit the new information into the information you already have.

- Imagine a young child who has only ever seen small, domesticated dogs. When the child sees a cat for the first time, they might refer to it as a “dog” because it has four legs, fur, and a tail – features that fit their existing schema of a dog.

- A person who has always believed that all birds can fly might label penguins as birds that can fly. This is because their existing schema or understanding of birds includes the ability to fly.

- A 2-year-old child sees a man who is bald on top of his head and has long frizzy hair on the sides. To his father’s horror, the toddler shouts “Clown, clown” (Siegler et al., 2003).

- If a baby learns to pick up a rattle he or she will then use the same schema (grasping) to pick up other objects.

6. Accommodation

Accommodation: when the new experience is very different from what we have encountered before we need to change our schemas in a very radical way or create a whole new schema.

Psychologist Jean Piaget defined accommodation as the cognitive process of revising existing cognitive schemas, perceptions, and understanding so that new information can be incorporated.

This happens when the existing schema (knowledge) does not work, and needs to be changed to deal with a new object or situation.

In order to make sense of some new information, you actually adjust information you already have (schemas you already have, etc.) to make room for this new information.

- A baby tries to use the same schema for grasping to pick up a very small object. It doesn’t work. The baby then changes the schema by now using the forefinger and thumb to pick up the object.

- A child may have a schema for birds (feathers, flying, etc.) and then they see a plane, which also flies, but would not fit into their bird schema.

- In the “clown” incident, the boy’s father explained to his son that the man was not a clown and that even though his hair was like a clown’s, he wasn’t wearing a funny costume and wasn’t doing silly things to make people laugh. With this new knowledge, the boy was able to change his schema of “clown” and make this idea fit better to a standard concept of “clown”.

- A person who grew up thinking all snakes are dangerous might move to an area where garden snakes are common and harmless. Over time, after observing and learning, they might accommodate their previous belief to understand that not all snakes are harmful.

7. Equilibration

Piaget believed that all human thought seeks order and is uncomfortable with contradictions and inconsistencies in knowledge structures. In other words, we seek “equilibrium” in our cognitive structures.

Equilibrium occurs when a child’s schemas can deal with most new information through assimilation. However, an unpleasant state of disequilibrium occurs when new information cannot be fitted into existing schemas (assimilation).

Piaget believed that cognitive development did not progress at a steady rate, but rather in leaps and bounds. Equilibration is the force which drives the learning process as we do not like to be frustrated and will seek to restore balance by mastering the new challenge (accommodation).

Once the new information is acquired the process of assimilation with the new schema will continue until the next time we need to make an adjustment to it.

Equilibration is a regulatory process that maintains a balance between assimilation and accommodation to facilitate cognitive growth. Think of it this way: We can’t merely assimilate all the time; if we did, we would never learn any new concepts or principles.

Everything new we encountered would just get put in the same few “slots” we already had. Neither can we accommodate all the time; if we did, everything we encountered would seem new; there would be no recurring regularities in our world. We’d be exhausted by the mental effort!

Applications to Education

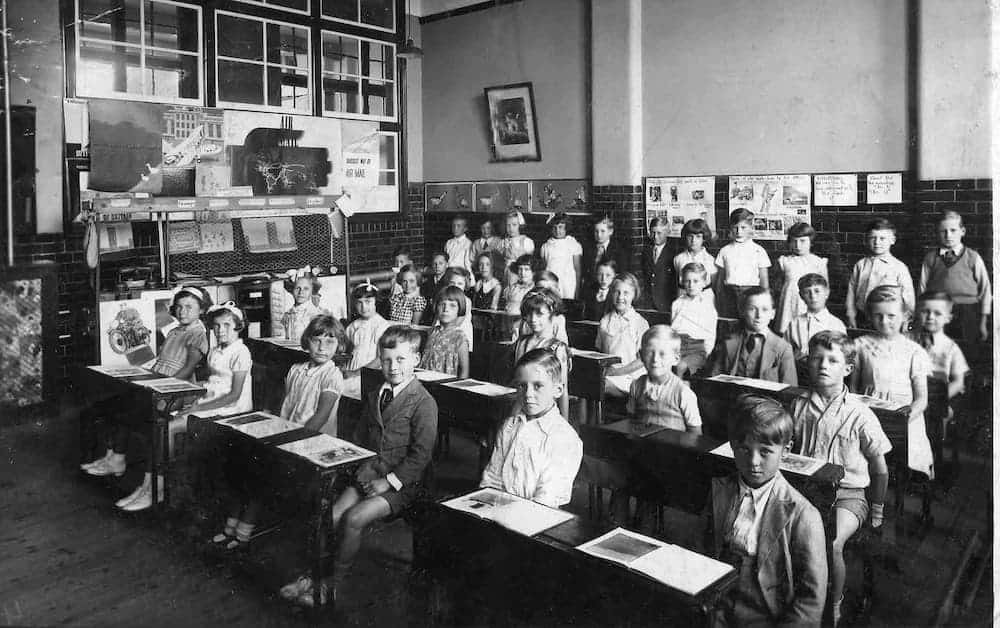

Think of old black and white films that you’ve seen in which children sat in rows at desks, with ink wells, would learn by rote, all chanting in unison in response to questions set by an authoritarian old biddy like Matilda!

Children who were unable to keep up were seen as slacking and would be punished by variations on the theme of corporal punishment. Yes, it really did happen and in some parts of the world still does today.

Piaget is partly responsible for the change that occurred in the 1960s and for your relatively pleasurable and pain-free school days!

“Children should be able to do their own experimenting and their own research. Teachers, of course, can guide them by providing appropriate materials, but the essential thing is that in order for a child to understand something, he must construct it himself, he must re-invent it. Every time we teach a child something, we keep him from inventing it himself. On the other hand that which we allow him to discover by himself will remain with him visibly”. Piaget (1972, p. 27)

Plowden Report

Piaget (1952) did not explicitly relate his theory to education, although later researchers have explained how features of Piaget’s theory can be applied to teaching and learning.

Piaget has been extremely influential in developing educational policy and teaching practice. For example, a review of primary education by the UK government in 1966 was based strongly on Piaget’s theory. The result of this review led to the publication of the Plowden Report (1967).

In the 1960s the Plowden Committee investigated the deficiencies in education and decided to incorporate many of Piaget’s ideas into its final report published in 1967, even though Piaget’s work was not really designed for education.

The report makes three Piaget-associated recommendations:

- Children should be given individual attention and it should be realized that they need to be treated differently.

- Children should only be taught things that they are capable of learning

- Children mature at different rates and the teacher needs to be aware of the stage of development of each child so teaching can be tailored to their individual needs.

“The report’s recurring themes are individual learning, flexibility in the curriculum, the centrality of play in children’s learning, the use of the environment, learning by discovery and the importance of the evaluation of children’s progress – teachers should “not assume that only what is measurable is valuable.”

Discovery learning – the idea that children learn best through doing and actively exploring – was seen as central to the transformation of the primary school curriculum.

How to teach

Within the classroom learning should be student-centered and accomplished through active discovery learning. The role of the teacher is to facilitate learning, rather than direct tuition.

Because Piaget’s theory is based upon biological maturation and stages, the notion of “readiness” is important. Readiness concerns when certain information or concepts should be taught.

According to Piaget’s theory, children should not be taught certain concepts until they have reached the appropriate stage of cognitive development.

According to Piaget (1958), assimilation and accommodation require an active learner, not a passive one, because problem-solving skills cannot be taught, they must be discovered.

Therefore, teachers should encourage the following within the classroom:

- Educational programs should be designed to correspond to Piaget’s stages of development. Children in the concrete operational stage should be given concrete means to learn new concepts e.g. tokens for counting.

- Devising situations that present useful problems, and create disequilibrium in the child.

- Focus on the process of learning, rather than the end product of it. Instead of checking if children have the right answer, the teacher should focus on the student’s understanding and the processes they used to get to the answer.

- Child-centered approach. Learning must be active (discovery learning). Children should be encouraged to discover for themselves and to interact with the material instead of being given ready-made knowledge.

- Accepting that children develop at different rates so arrange activities for individual children or small groups rather than assume that all the children can cope with a particular activity.

- Using active methods that require rediscovering or reconstructing “truths.”

- Using collaborative, as well as individual activities (so children can learn from each other).

- Evaluate the level of the child’s development so suitable tasks can be set.

- Adapt lessons to suit the needs of the individual child (i.e. differentiated teaching).

- Be aware of the child’s stage of development (testing).

- Teach only when the child is ready. i.e. has the child reached the appropriate stage.

- Providing support for the “spontaneous research” of the child.

- Using collaborative, as well as individual activities.

- Educators may use Piaget’s stages to design age-appropriate assessment tools and strategies.

Classroom Activities

Sensorimotor stage (0-2 years):.

Although most kids in this age range are not in a traditional classroom setting, they can still benefit from games that stimulate their senses and motor skills.

- Object Permanence Games : Play peek-a-boo or hide toys under a blanket to help babies understand that objects still exist even when they can’t see them.

- Sensory Play : Activities like water play, sand play, or playdough encourage exploration through touch.

- Imitation : Children at this age love to imitate adults. Use imitation as a way to teach new skills.

Preoperational Stage (2-7 years):

- Role Playing : Set up pretend play areas where children can act out different scenarios, such as a kitchen, hospital, or market.

- Use of Symbols : Encourage drawing, building, and using props to represent other things.

- Hands-on Activities : Children should interact physically with their environment, so provide plenty of opportunities for hands-on learning.

- Egocentrism Activities : Use exercises that highlight different perspectives. For instance, having two children sit across from each other with an object in between and asking them what the other sees.

Concrete Operational Stage (7-11 years):

- Classification Tasks : Provide objects or pictures to group, based on various characteristics.

- Hands-on Experiments : Introduce basic science experiments where they can observe cause and effect, like a simple volcano with baking soda and vinegar.

- Logical Games : Board games, puzzles, and logic problems help develop their thinking skills.

- Conservation Tasks : Use experiments to showcase that quantity doesn’t change with alterations in shape, such as the classic liquid conservation task using different shaped glasses.

Formal Operational Stage (11 years and older):

- Hypothesis Testing : Encourage students to make predictions and test them out.

- Abstract Thinking : Introduce topics that require abstract reasoning, such as algebra or ethical dilemmas.

- Problem Solving : Provide complex problems and have students work on solutions, integrating various subjects and concepts.

- Debate and Discussion : Encourage group discussions and debates on abstract topics, highlighting the importance of logic and evidence.

- Feedback and Questioning : Use open-ended questions to challenge students and promote higher-order thinking. For instance, rather than asking, “Is this the right answer?”, ask, “How did you arrive at this conclusion?”

While Piaget’s stages offer a foundational framework, they are not universally experienced in the same way by all children.

Social identities play a critical role in shaping cognitive development, necessitating a more nuanced and culturally responsive approach to understanding child development.

Piaget’s stages may manifest differently based on social identities like race, gender, and culture:

- Race & Teacher Interactions : A child’s race can influence teacher expectations and interactions. For example, racial biases can lead to children of color being perceived as less capable or more disruptive, influencing their cognitive challenges and supports.

- Racial and Cultural Stereotypes : These can affect a child’s self-perception and self-efficacy . For instance, stereotypes about which racial or cultural groups are “better” at certain subjects can influence a child’s self-confidence and, subsequently, their engagement in that subject.

- Gender & Peer Interactions : Children learn gender roles from their peers. Boys might be mocked for playing “girl games,” and girls might be excluded from certain activities, influencing their cognitive engagements.

- Language : Multilingual children might navigate the stages differently, especially if their home language differs from their school language. The way concepts are framed in different languages can influence cognitive processing. Cultural idioms and metaphors can shape a child’s understanding of concepts and their ability to use symbolic representation, especially in the pre-operational stage.

Curriculum Development

According to Piaget, children’s cognitive development is determined by a process of maturation which cannot be altered by tuition so education should be stage-specific.

For example, a child in the concrete operational stage should not be taught abstract concepts and should be given concrete aid such as tokens to count with.

According to Piaget children learn through the process of accommodation and assimilation so the role of the teacher should be to provide opportunities for these processes to occur such as new material and experiences that challenge the children’s existing schemas.

Furthermore, according to this theory, children should be encouraged to discover for themselves and to interact with the material instead of being given ready-made knowledge.

Curricula need to be developed that take into account the age and stage of thinking of the child. For example there is no point in teaching abstract concepts such as algebra or atomic structure to children in primary school.

Curricula also need to be sufficiently flexible to allow for variations in the ability of different students of the same age. In Britain, the National Curriculum and Key Stages broadly reflect the stages that Piaget laid down.

For example, egocentrism dominates a child’s thinking in the sensorimotor and preoperational stages. Piaget would therefore predict that using group activities would not be appropriate since children are not capable of understanding the views of others.

However, Smith et al. (1998), point out that some children develop earlier than Piaget predicted and that by using group work children can learn to appreciate the views of others in preparation for the concrete operational stage.

The national curriculum emphasizes the need to use concrete examples in the primary classroom.

Shayer (1997), reported that abstract thought was necessary for success in secondary school (and co-developed the CASE system of teaching science). Recently the National curriculum has been updated to encourage the teaching of some abstract concepts towards the end of primary education, in preparation for secondary courses. (DfEE, 1999).

Child-centered teaching is regarded by some as a child of the ‘liberal sixties.’ In the 1980s the Thatcher government introduced the National Curriculum in an attempt to move away from this and bring more central government control into the teaching of children.

So, although the British National Curriculum in some ways supports the work of Piaget, (in that it dictates the order of teaching), it can also be seen as prescriptive to the point where it counters Piaget’s child-oriented approach.

However, it does still allow for flexibility in teaching methods, allowing teachers to tailor lessons to the needs of their students.

Social Media (Digital Learning)

Jean Piaget could not have anticipated the expansive digital age we now live in.

Today, knowledge dissemination and creation are democratized by the Internet, with platforms like blogs, wikis, and social media allowing for vast collaboration and shared knowledge. This development has prompted a reimagining of the future of education.

Classrooms, traditionally seen as primary sites of learning, are being overshadowed by the rise of mobile technologies and platforms like MOOCs (Passey, 2013).

The millennial generation, defined as the first to grow up with cable TV, the internet, and cell phones, relies heavily on technology.

They view it as an integral part of their identity, with most using it extensively in their daily lives, from keeping in touch with loved ones to consuming news and entertainment (Nielsen, 2014).

Social media platforms offer a dynamic environment conducive to Piaget’s principles. These platforms allow for interactions that nurture knowledge evolution through cognitive processes like assimilation and accommodation.

They emphasize communal interaction and shared activity, fostering both cognitive and socio-cultural constructivism. This shared activity promotes understanding and exploration beyond individual perspectives, enhancing social-emotional learning (Gehlbach, 2010).

A standout advantage of social media in an educational context is its capacity to extend beyond traditional classroom confines. As the material indicates, these platforms can foster more inclusive learning, bridging diverse learner groups.

This inclusivity can equalize learning opportunities, potentially diminishing biases based on factors like race or socio-economic status, resonating with Kegan’s (1982) concept of “recruitability.”

However, there are challenges. While the potential of social media in learning is vast, its practical application necessitates intention and guidance. Cuban, Kirkpatrick, and Peck (2001) note that certain educators and students are hesitant about integrating social media into educational contexts.

This hesitancy can stem from technological complexities or potential distractions. Yet, when harnessed effectively, social media can provide a rich environment for collaborative learning and interpersonal development, fostering a deeper understanding of content.

In essence, the rise of social media aligns seamlessly with constructivist philosophies. Social media platforms act as tools for everyday cognition, merging daily social interactions with the academic world, and providing avenues for diverse, interactive, and engaging learning experiences.

Applications to Parenting

Parents can use Piaget’s stages to have realistic developmental expectations of their children’s behavior and cognitive capabilities.

For instance, understanding that a toddler is in the pre-operational stage can help parents be patient when the child is egocentric.

Play Activities

Recognizing the importance of play in cognitive development, many parents provide toys and games suited for their child’s developmental stage.

Parents can offer activities that are slightly beyond their child’s current abilities, leveraging Vygotsky’s concept of the “Zone of Proximal Development,” which complements Piaget’s ideas.

- Peek-a-boo : Helps with object permanence.

- Texture Touch : Provide different textured materials (soft, rough, bumpy, smooth) for babies to touch and feel.

- Sound Bottles : Fill small bottles with different items like rice, beans, bells, and have children shake and listen to the different sounds.

- Memory Games : Using cards with pictures, place them face down, and ask students to find matching pairs.

- Role Playing and Pretend Play : Let children act out roles or stories that enhance symbolic thinking. Encourage symbolic play with dress-up clothes, playsets, or toy cash registers. Provide prompts or scenarios to extend their imagination.

- Story Sequencing : Give children cards with parts of a story and have them arranged in the correct order.

- Number Line Jumps : Create a number line on the floor with tape. Ask students to jump to the correct answer for math problems.

- Classification Games : Provide a mix of objects and ask students to classify them based on different criteria (e.g., color, size, shape).

- Logical Puzzle Games : Games that involve problem-solving using logic, such as simple Sudoku puzzles or logic grid puzzles.

- Debate and Discussion : Provide a topic and let students debate on pros and cons. This promotes abstract thinking and logical reasoning.

- Hypothesis Testing Games : Present a scenario and have students come up with hypotheses and ways to test them.

- Strategy Board Games : Games like chess, checkers, or Settlers of Catan can help in developing strategic and forward-thinking skills.

Critical Evaluation

- The influence of Piaget’s ideas on developmental psychology has been enormous. He changed how people viewed the child’s world and their methods of studying children.

He was an inspiration to many who came after and took up his ideas. Piaget’s ideas have generated a huge amount of research which has increased our understanding of cognitive development.

- Piaget (1936) was one of the first psychologists to make a systematic study of cognitive development. His contributions include a stage theory of child cognitive development, detailed observational studies of cognition in children, and a series of simple but ingenious tests to reveal different cognitive abilities.

- His ideas have been of practical use in understanding and communicating with children, particularly in the field of education (re: Discovery Learning). Piaget’s theory has been applied across education.

- According to Piaget’s theory, educational programs should be designed to correspond to the stages of development.

- Are the stages real? Vygotsky and Bruner would rather not talk about stages at all, preferring to see development as a continuous process. Others have queried the age ranges of the stages. Some studies have shown that progress to the formal operational stage is not guaranteed.

For example, Keating (1979) reported that 40-60% of college students fail at formal operation tasks, and Dasen (1994) states that only one-third of adults ever reach the formal operational stage.

The fact that the formal operational stage is not reached in all cultures and not all individuals within cultures suggests that it might not be biologically based.

- According to Piaget, the rate of cognitive development cannot be accelerated as it is based on biological processes however, direct tuition can speed up the development which suggests that it is not entirely based on biological factors.

- Because Piaget concentrated on the universal stages of cognitive development and biological maturation, he failed to consider the effect that the social setting and culture may have on cognitive development.

Cross-cultural studies show that the stages of development (except the formal operational stage) occur in the same order in all cultures suggesting that cognitive development is a product of a biological process of maturation.

However, the age at which the stages are reached varies between cultures and individuals which suggests that social and cultural factors and individual differences influence cognitive development.

Dasen (1994) cites studies he conducted in remote parts of the central Australian desert with 8-14-year-old Indigenous Australians. He gave them conservation of liquid tasks and spatial awareness tasks. He found that the ability to conserve came later in the Aboriginal children, between ages of 10 and 13 (as opposed to between 5 and 7, with Piaget’s Swiss sample).

However, he found that spatial awareness abilities developed earlier amongst the Aboriginal children than the Swiss children. Such a study demonstrates cognitive development is not purely dependent on maturation but on cultural factors too – spatial awareness is crucial for nomadic groups of people.

Vygotsky , a contemporary of Piaget, argued that social interaction is crucial for cognitive development. According to Vygotsky the child’s learning always occurs in a social context in cooperation with someone more skillful (MKO). This social interaction provides language opportunities and Vygotsky considered language the foundation of thought.

- Piaget’s methods (observation and clinical interviews) are more open to biased interpretation than other methods. Piaget made careful, detailed naturalistic observations of children, and from these, he wrote diary descriptions charting their development. He also used clinical interviews and observations of older children who were able to understand questions and hold conversations.

Because Piaget conducted the observations alone the data collected are based on his own subjective interpretation of events. It would have been more reliable if Piaget conducted the observations with another researcher and compared the results afterward to check if they are similar (i.e., have inter-rater reliability).

Although clinical interviews allow the researcher to explore data in more depth, the interpretation of the interviewer may be biased.

For example, children may not understand the question/s, they have short attention spans, they cannot express themselves very well, and may be trying to please the experimenter. Such methods meant that Piaget may have formed inaccurate conclusions.

- As several studies have shown Piaget underestimated the abilities of children because his tests were sometimes confusing or difficult to understand (e.g., Hughes , 1975).

Piaget failed to distinguish between competence (what a child is capable of doing) and performance (what a child can show when given a particular task). When tasks were altered, performance (and therefore competence) was affected. Therefore, Piaget might have underestimated children’s cognitive abilities.

For example, a child might have object permanence (competence) but still not be able to search for objects (performance). When Piaget hid objects from babies he found that it wasn’t till after nine months that they looked for it.

However, Piaget relied on manual search methods – whether the child was looking for the object or not.

Later, researchers such as Baillargeon and Devos (1991) reported that infants as young as four months looked longer at a moving carrot that didn’t do what it expected, suggesting they had some sense of permanence, otherwise they wouldn’t have had any expectation of what it should or shouldn’t do.

- The concept of schema is incompatible with the theories of Bruner (1966) and Vygotsky (1978). Behaviorism would also refute Piaget’s schema theory because is cannot be directly observed as it is an internal process. Therefore, they would claim it cannot be objectively measured.

- Piaget studied his own children and the children of his colleagues in Geneva to deduce general principles about the intellectual development of all children. His sample was very small and composed solely of European children from families of high socio-economic status. Researchers have, therefore, questioned the generalisability of his data.

- For Piaget, language is considered secondary to action, i.e., thought precedes language. The Russian psychologist Lev Vygotsky (1978) argues that the development of language and thought go together and that the origin of reasoning has more to do with our ability to communicate with others than with our interaction with the material world.

Piaget’s Theory vs Vygotsky

Piaget maintains that cognitive development stems largely from independent explorations in which children construct knowledge of their own.

Whereas Vygotsky argues that children learn through social interactions, building knowledge by learning from more knowledgeable others such as peers and adults. In other words, Vygotsky believed that culture affects cognitive development.

These factors lead to differences in the education style they recommend: Piaget would argue for the teacher to provide opportunities that challenge the children’s existing schemas and for children to be encouraged to discover for themselves.

Alternatively, Vygotsky would recommend that teachers assist the child to progress through the zone of proximal development by using scaffolding.

However, both theories view children as actively constructing their own knowledge of the world; they are not seen as just passively absorbing knowledge.

They also agree that cognitive development involves qualitative changes in thinking, not only a matter of learning more things.

What is cognitive development?

Cognitive development is how a person’s ability to think, learn, remember, problem-solve, and make decisions changes over time.

This includes the growth and maturation of the brain, as well as the acquisition and refinement of various mental skills and abilities.

Cognitive development is a major aspect of human development, and both genetic and environmental factors heavily influence it. Key domains of cognitive development include attention, memory, language skills, logical reasoning, and problem-solving.

Various theories, such as those proposed by Jean Piaget and Lev Vygotsky, provide different perspectives on how this complex process unfolds from infancy through adulthood.

What are the 4 stages of Piaget’s theory?

Piaget divided children’s cognitive development into four stages; each of the stages represents a new way of thinking and understanding the world.

He called them (1) sensorimotor intelligence , (2) preoperational thinking , (3) concrete operational thinking , and (4) formal operational thinking . Each stage is correlated with an age period of childhood, but only approximately.

According to Piaget, intellectual development takes place through stages that occur in a fixed order and which are universal (all children pass through these stages regardless of social or cultural background).

Development can only occur when the brain has matured to a point of “readiness”.

What are some of the weaknesses of Piaget’s theory?

Cross-cultural studies show that the stages of development (except the formal operational stage) occur in the same order in all cultures suggesting that cognitive development is a product of a biological maturation process.

However, the age at which the stages are reached varies between cultures and individuals, suggesting that social and cultural factors and individual differences influence cognitive development.

What are Piaget’s concepts of schemas?

Schemas are mental structures that contain all of the information relating to one aspect of the world around us.

According to Piaget, we are born with a few primitive schemas, such as sucking, which give us the means to interact with the world.

These are physical, but as the child develops, they become mental schemas. These schemas become more complex with experience.

Baillargeon, R., & DeVos, J. (1991). Object permanence in young infants: Further evidence . Child development , 1227-1246.

Bruner, J. S. (1966). Toward a theory of instruction. Cambridge, Mass.: Belkapp Press.

Cuban, L., Kirkpatrick, H., & Peck, C. (2001). High access and low use of technologies in high school classrooms: Explaining an apparent paradox. American Educational Research Journal , 38 (4), 813-834.

Dasen, P. (1994). Culture and cognitive development from a Piagetian perspective. In W .J. Lonner & R.S. Malpass (Eds.), Psychology and culture (pp. 145–149). Boston, MA: Allyn and Bacon.

Gehlbach, H. (2010). The social side of school: Why teachers need social psychology. Educational Psychology Review , 22 , 349-362.

Hughes, M. (1975). Egocentrism in preschool children . Unpublished doctoral dissertation. Edinburgh University.

Inhelder, B., & Piaget, J. (1958). The growth of logical thinking from childhood to adolescence . New York: Basic Books.

Keating, D. (1979). Adolescent thinking. In J. Adelson (Ed.), Handbook of adolescent psychology (pp. 211-246). New York: Wiley.

Kegan, R. (1982). The evolving self: Problem and process in human development . Harvard University Press.

Nielsen. 2014. “Millennials: Technology = Social Connection.” http://www.nielsen.com/content/corporate/us/en/insights/news/2014/millennials-technology-social-connecti on.html.

Passey, D. (2013). Inclusive technology enhanced learning: Overcoming cognitive, physical, emotional, and geographic challenges . Routledge.

Piaget, J. (1932). The moral judgment of the child . London: Routledge & Kegan Paul.

Piaget, J. (1936). Origins of intelligence in the child. London: Routledge & Kegan Paul.

Piaget, J. (1945). Play, dreams and imitation in childhood . London: Heinemann.

Piaget, J. (1957). Construction of reality in the child. London: Routledge & Kegan Paul.

Piaget, J., & Cook, M. T. (1952). The origins of intelligence in children . New York, NY: International University Press.

Piaget, J. (1981). Intelligence and affectivity: Their relationship during child development.(Trans & Ed TA Brown & CE Kaegi) . Annual Reviews.

Plowden, B. H. P. (1967). Children and their primary schools: A report (Research and Surveys). London, England: HM Stationery Office.

Siegler, R. S., DeLoache, J. S., & Eisenberg, N. (2003). How children develop . New York: Worth.

Vygotsky, L. S. (1978). Mind in society: The development of higher psychological processes . Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Wadsworth, B. J. (2004). Piaget’s theory of cognitive and affective development: Foundations of constructivism . New York: Longman.

Further Reading

- BBC Radio Broadcast about the Three Mountains Study

- Piagetian stages: A critical review

- Bronfenbrenner’s Ecological Systems Theory

Related Articles

Child Psychology

Vygotsky vs. Piaget: A Paradigm Shift

Interactional Synchrony

Internal Working Models of Attachment

Soft Determinism In Psychology

Branches of Psychology

Cognitive Psychology

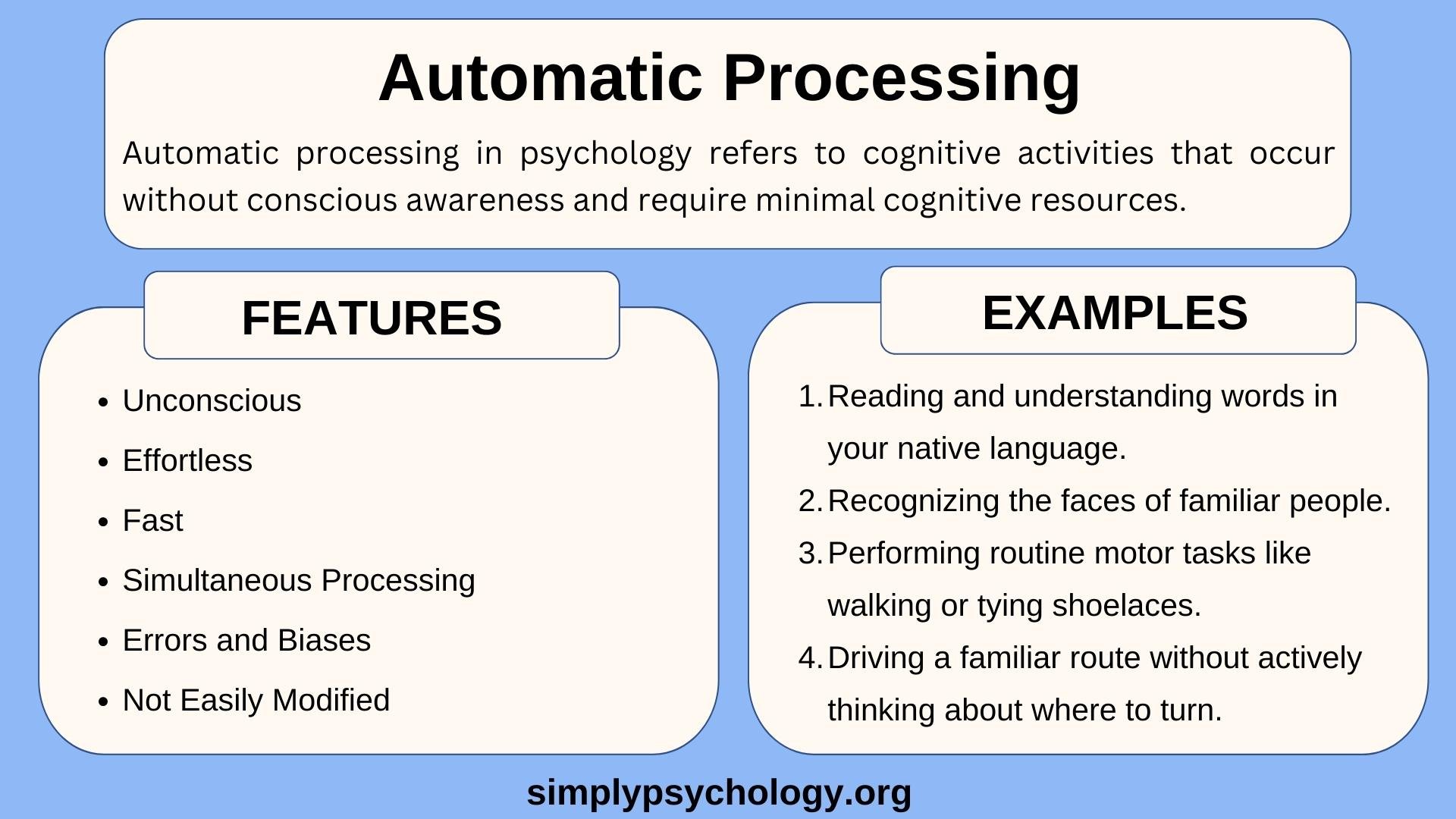

Automatic Processing in Psychology: Definition & Examples

Piaget’s Stages: 4 Stages of Cognitive Development & Theory

You’re trying to explain something to a child, and even though it seems so obvious to you, the child just doesn’t seem to understand.

They repeat the same mistake, over and over, and you become increasingly frustrated.

Well, guess what?

- The child is not naughty.

- They’re also not stupid.

- But their lack of understanding is not your fault either.

Their cognitive development limits their ability to understand certain concepts. Specifically, they’re not capable right now of understanding what you’re trying to explain.

In this post, we’ll learn more about Jean Piaget, a famous psychologist whose ideas about cognitive development in children were extremely influential. We’ll cover quite a lot in this post, so make sure you have a cup of coffee and you’re sitting somewhere comfortable.

Before you continue, we thought you might like to download our three Positive Psychology Exercises for free . These science-based exercises explore fundamental aspects of positive psychology, including strengths, values, and self-compassion, and will give you the tools to enhance the wellbeing of your clients, students, or employees.

This Article Contains:

Who was jean piaget in psychology, piaget’s cognitive development theory, 1. the sensorimotor stage, 2. the preoperational stage, 3. the concrete operational stage, 4. the formal operational stage, piaget’s theory vs erikson’s, 5 important concepts in piaget’s work, applications in education (+3 classroom games), positivepsychology.com’s relevant resources, a take-home message.