Knowledge is power

Stay in the know about climate impacts and solutions. Subscribe to our weekly newsletter.

By clicking submit, you agree to share your email address with the site owner and Mailchimp to receive emails from the site owner. Use the unsubscribe link in those emails to opt out at any time.

Yale Climate Connections

Pros and cons of fracking: 5 key issues

Share this:

- Click to share on Facebook (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on X (Opens in new window)

There’s an issue where the underlying science remains a political football, and scientists are regularly challenged and called out personally . Where energy needs and short-term economic growth are set against our children’s health and future. Where the consequences of bad, short-sighted decisions may be borne primarily by a small subset of under-served and undeserving persons. And where the very descriptive terms in the debate are radioactive, words spun as epithets.

We’re not talking here about global warming, and “deniers” versus “warmists.” We’re talking about the game-changing new set of unconventional oil and gas extraction technologies and techniques collectively known as hydraulic fracturing , or “fracking.”

Ask the most hardcore of pro-fracking boosters for their take, and they’ll describe the modern miracle of America’s new-found energy independence, a reality almost inconceivable just a decade ago. For them, the oil and gas boom around the U.S. has helped to reboot the economy at a time of great need. Prices at the pump have plummeted. Sure, they may acknowledge, there are a few safety issues to be worked out and techniques yet to be perfected, but just look at the big picture.

Fracking detractors in environmental and social justice circles, meanwhile, will conjure up the iconic image: Flammable water flowing from a home faucet. And with that come other haunting images: The double-crossed landowner hapless in the face of aggressive Big Energy. The ugly rigs rising up amid the tranquility of America’s farm, pasture, and suburban lands. The stench of unknown – even secret – chemicals, sickness, and looming illnesses, and death.

Refereeing these confrontations is no easy thing, and unlike the “settled science” of climate change and its causes, the science of fracking is far from settled. But a review of the research can help clarify some of the chief points of contention.

If there’s a single source plausibly seen as the fairest, most comprehensive, and cogent assessment, it might be the 2014 literature review published in Annual Reviews of Environment and Resources . It’s titled “ The Environmental Costs and Benefits of Fracking ,” authored by researchers affiliated with leading universities and research organizations who reviewed more than 160 studies.

Below are the arguments and synthesized evidence on some key issues, based on the available research literature and conversations with diverse experts.

Air quality, health, and the energy menu

ISSUE: The new supply of natural gas reachable by fracking is now changing the overall picture for U.S. electricity generation, with consequences for air quality.

PRO FRACKING: Increasing reliance on natural gas, rather than coal, is indisputably creating widespread public health benefits, as the burning of natural gas produces fewer harmful particles in the air. The major new supply of natural gas produced through fracking is displacing the burning of coal, which each year contributes to the early death of thousands of people. Coal made up about 50 percent of U.S. electricity generation in 2008, 37 percent by 2012; meanwhile, natural gas went from about 20 percent to about 30 percent during that same period. In particular, nitrogen oxide and sulfur dioxide emissions have been reduced dramatically . Fracking saves lives, and it saves them right now and not at some indiscernible date well into the future.

CON FRACKING: First, it is not the case that a new natural gas facility coming online always replaces a legacy coal-fired power plant. It may displace coal in West Virginia or North Carolina, but less so in Texas and across the West. So fracking is no sure bet for improving regional air quality. Second, air quality dynamics around fracking operations are not fully understood, and cumulative health impacts of fracking for nearby residents and workers remain largely unknown. Some of the available research evidence from places such as Utah and Colorado suggests there may be under-appreciated problems with air quality, particularly relating to ozone. Further, natural gas is not a purely clean and renewable source of energy, and so its benefits are only relative. It is not the answer to truly cleaning up our air, and in fact could give pause to a much-needed and well thought-out transition to wind, solar, geothermal, and other sources that produce fewer or no harmful airborne fine particulates.

Greenhouse gas leaks, methane and fugitive emissions

ISSUE: The extraction process results in some greenhouse gas emissions leakage.

PRO FRACKING: We know that, at the power plant level, natural gas produces only somewhere between 44 and 50 percent of the greenhouse gas emissions compared with burning of coal. This is known for certain; it’s basic chemistry. That is a gigantic benefit. Further, some research that claims methane is so harmful uses a 20-year time horizon; but over a 100-year time horizon – the way we generally measure global warming potential – methane is not nearly so harmful as claimed. Thus, methane’s impact is potent but relatively brief compared with impacts of increased carbon dioxide emissions. The number-one priority must be to reduce the reliance on coal, the biggest threat to the atmosphere right now. Fears about emissions leaks are overblown. Even if the true leakage rate were slightly more than EPA and some states estimate, it is not that dramatic. We are developing technology to reduce these leaks and further narrow the gap. Moreover, research-based modeling suggests that even if energy consumption increases overall, the United States still will reap greenhouse benefits as a result of fracking.

CON FRACKING: Research from Cornell has suggested that leaked methane – a powerful greenhouse gas – from wells essentially wipes out any greenhouse gas benefits of natural gas derived from fracking. And at other points in the life cycle, namely transmission and distribution, there are further ample leaks. Falling natural gas prices will only encourage more energy use, negating any “cleaner” benefits of gas. Finally, there is no question that the embrace of cheap natural gas will undercut incentives to invest in solar, wind, and other renewables. We are at a crucial juncture over the next few decades in terms of reducing the risk of “tipping points” and catastrophic melting of the glaciers. Natural gas is often seen as a “bridge,” but it is likely a bridge too far, beyond the point where scientists believe we can go in terms of greenhouse gas levels in the atmosphere.

Drinking water wars

ISSUE: Fracking may threaten human health by contaminating drinking water supplies.

PRO FRACKING: It is highly unlikely that well-run drilling operations, which involve extracting oil and gas from thousands of feet down in the ground, are creating cracks that allow chemicals to reach relatively shallow aquifers and surface water supplies. Drinking water and oil and gas deposits are at very different levels in the ground. To the extent that there are problems, we must make sure companies pay more attention to the surface operations and the top 500 to 1,000 feet of piping. But that’s not the fracking – that’s just a matter of making sure that the steel tubing, the casing, is not leaking and that the cement around it doesn’t have cracks. Certain geologies, such as those in Pennsylvania’s Marcellus Shale region, do require more care; but research has found that between 2008 and 2011, only a handful of major incidents happened across more than 3,500 wells in the Marcellus. We are learning and getting better. So this is a technical, well-integrity issue, not a deal-breaker. As for the flammable water, it is a fact that flammable water was a reality 100 years ago in some of these areas. It can be made slightly worse in a minority of cases, but it’s unlikely and it is often the result of leaks from activities other than fracking. In terms of disclosure, many of the chemicals are listed on data sheets available to first-responders: The information is disclosed to relevant authorities.

CON FRACKING: This April, yet another major study , published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences , confirmed that high-volume hydraulic fracturing techniques can contaminate drinking water. There have been numerous reports by citizens across the country of fouled tap water; it is a fact that some of the tap water has even turned bubbly and flammable, as a result of increased methane. Well blowouts have happened, and they are a complete hazard to the environment. The companies involved cannot be trusted, and roughly one in five chemicals involved in the fracking process are still classified as trade secrets. Even well-meaning disclosure efforts such as FracFocus.org do not provide sufficient information. And we know that there are many who cut corners out in the field, no matter the federal or state regulations we try to impose. They already receive dozens of violation notices at sites, with little effect. We’ve created a Gold Rush/Wild West situation by green-lighting all of this drilling, and in the face of these economic incentives, enforcement has little impact.

Infrastructure, resources, and communities

ISSUE: Fracking operations are sometimes taking place near and around populated areas, with consequences for the local built and natural environments.

PRO FRACKING: Water intensity is lower for fracking than other fossil fuels and nuclear: Coal, nuclear and oil extraction use approximately two, three, and 10 times, respectively, as much water as fracking per energy unit, and corn ethanol may use 1,000 times more if the plants are irrigated. For communities, the optics, aesthetics, and quality of life issues are real, but it’s worth remembering that drilling operations and rigs don’t go on forever – it’s not like putting up a permanent heavy manufacturing facility. The operations are targeted and finite, and the productivity of wells is steadily rising , getting more value during operations. Moreover, the overall societal benefits outweigh the downsides, which are largely subjective in this respect.

CON FRACKING: More than 15 million Americans have had a fracking operation within a mile of their home. Still, that means that a small proportion of people shoulder the burden and downsides, with no real compensation for this intrusive new industrial presence. Fracking is hugely water-intensive: A well can require anywhere from two- to 20-million gallons of water, with another 25 percent used for operations such as drilling and extraction. It can impact local water sources. The big, heavy trucks beat up our roads over hundreds of trips back-and-forth – with well-documented consequences for local budgets and infrastructure. In places such as Pennsylvania, Ohio, and Colorado, the drilling rigs have popped up near where people have their homes, diminishing the quality of life and creating an industrial feel to some of our communities. This is poor planning at best, and sheer greed at its worst. It seldom involves the preferences of the local residents.

Finally, it’s also the case that relatively low impact fees are being charged and relatively little funding is being set aside to mitigate future problems as wells age and further clean-up is necessary. It is the opposite of a sustainable solution, as well production tends to drop sharply after initial fracking. Within just five years, wells may produce just 10 percent of what they did in the first month of operation. In short order, we’re likely to have tens of thousands of sealed and abandoned wells all over the U.S. landscape, many of which will need to be monitored, reinforced, and maintained. It is a giant unfunded scheme.

Earthquakes: Seismic worries

ISSUE: Fracking wells, drilled thousands of feet down, may change geology in a potentially negative way, leading to earthquakes.

PRO FRACKING: Earthquakes are a naturally occurring phenomenon, and even in the few instances where fracking operations likely contributed to them, they were minor. We’ve had tens of thousands of wells drilled over many years now, and there are practically zero incidents in which operations-induced seismic effects impacted citizens. There’s also research to suggest that the potential for earthquakes can be mitigated through safeguards.

CON FRACKING: We are only just beginning to understand what we are doing to our local geologies, and this is dangerous. The 2014 Annual Reviews of Environment and Resources paper notes that “between 1967 and 2000, geologists observed a steady background rate of 21 earthquakes of 3.0 Mw or greater in the central United States per year. Starting in 2001, when shale gas and other unconventional energy sources began to grow, the rate rose steadily to [approximately] 100 such earthquakes annually, with 188 in 2011 alone.” New research on seismology in places such as Texas and Oklahoma suggests risky and unknown changes. It is just not smart policy to go headlong first – at massive scale – and only later discover the consequences.

Also see: Pros and cons of fracking: Research updates

John Wihbey

John Wihbey, a writer, educator, and researcher, is an assistant professor of journalism at Northeastern University and a correspondent for Boston Globe Ideas. Previously, he was an assistant director... More by John Wihbey

The economic benefits of fracking

Fred dews fred dews managing editor, new digital products - office of communications @publichistory.

March 23, 2015

Innovations in drilling and hydraulic fracturing (“fracking”) have enabled tremendous amounts of natural gas to be extracted from underground shale formations that were long thought to be uneconomical. But has this shale gas boom translated in an economic boom? According to Catherine Hausman and Ryan Kellogg, who shared the first-ever estimates of broad-scale welfare and distributional implications of fracking as part of the most recent conference of the Brookings Papers on Economic Activity (BPEA) , the answer is yes. Here’s why:

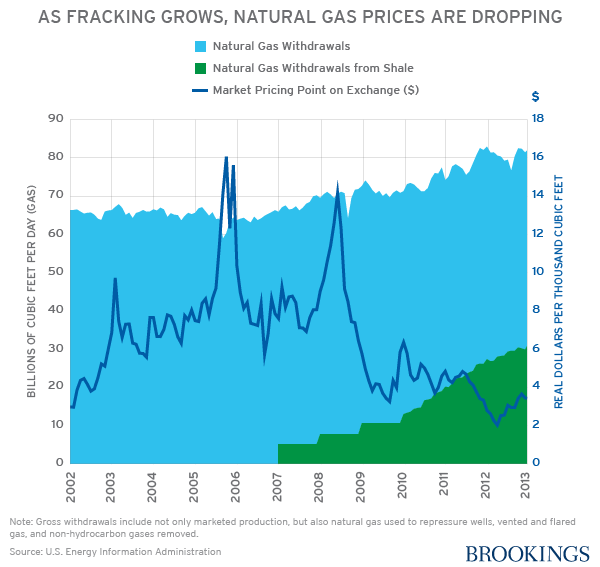

As fracking grows, natural gas prices are dropping

The U.S. fracking revolution has caused natural gas prices to drop 47 percent compared to what the price would have been prior to the fracking revolution in 2013.

Gas bills have dropped $13 billion per year from 2007 to 2013 as a result of increased fracking, which adds up to $200 per year for gas-consuming households. Moreover, all types of energy consumers, including commercial, industrial, and electric power consumers, saw economic gains totaling $74 billion per year from increased fracking.

Though one would expect colder states that use natural gas for space heating to benefit most from shale gas, the authors point out that the West South Central region (Arkansas, Louisiana, Oklahoma, and Texas) gained the most at $432 per person in consumer benefits, followed by East North Central (Illinois, Indiana, Michigan, Ohio, and Wisconsin) with $259 per person in benefits. The area to gain the least is the Pacific (California, Oregon, and Washington), but consumers there still benefited to the tune of $181 per year.

Despite economic gains, environmental concerns remain

In addition to exploring the economic consequences of the fracking boom, the authors also review fracking’s environmental impacts and discuss the difficulty facing regulators. They note that while scientists remain concerned about a number of environmental damages caused by fracking, the data collection has not kept pace with the boom in extraction, and a great deal of uncertainty remains regarding pollution from fracking.

To learn more about what fracking means for the U.S. economy, read the full paper by Catherine Hausman and Ryan Kellog here , and watch an interview with BPEA co-editor Justin Wolfers below.

Anthony F. Pipa

May 14, 2024

Tedros Adhanom-Ghebreyesus

May 9, 2024

Jenny Schuetz, Adie Tomer

May 6, 2024

University of Notre Dame

Fresh Writing

A publication of the University Writing Program

- Home ›

- Essays ›

By Will Weldon

Published: July 31, 2022

Arguably the most debated topic in modern society, climate change, is one strongly linked to the process of fracking. While fracking, in the minds of many Americans, is the champion of the United States energy industry, there are those who call for the elimination of the practice. Such opponents from the environmental health arena point to the risks the process poses to the environment and individual health, as well as to the widespread notion that the world must soon transition to renewable resources. Though many call for the immediate move away from fossil fuels in America, the relatively innocuous nature of natural gas makes it a prospective “transition fuel” to be used en route to clean energy. The question of whether or not fracking should continue in the United States deals with two systems which hold great power over the American citizen: the economy and the climate. While the sustained use of fossil fuels may have detrimental effects on Earth’s climate, the abolition of fracking in the United States will almost certainly leave the American economy devastated and render us dependent on foreign countries for energy. Such consequences have led to the development of two chief sides to the fracking debate. Either we should end fracking immediately in an attempt to prevent any further climate change, or we should gradually reduce the practice of fracking over time. In our current world, you will find the latter is far more economically, environmentally, and politically practical.

Hydraulic fracturing, or fracking, is a method of natural-gas-and-crude-oil extraction that involves the pumping of high-pressure fluid into underground rock formations. The fluid, which is typically a mixture of sand, water, and chemical additives, is used to fracture the rock layers and release natural gas and oil (“Fracking in the United States”). These resources then flow into a wellbore and are extracted to the surface. An additional technique used in the modern fracking industry is the process of horizontal drilling. This technology involves the well turning ninety degrees and extending horizontally along the desired rock layer, allowing fracking companies to maximize their output for each well. Horizontal drilling, as well as other developments achieved for fracking, including those in machinery and fluid, is partly responsible for the fracking industry’s boom in the United States (Denchak).

Since the turn of the century, the fracking industry has grown at an exponential rate across the United States. Technological developments have allowed fracking to successfully be applied to dense rock formations which were previously unusable, such as shale. Equally influential in the industry’s boom was the United States’s vulnerability to fluctuations in the global fossil fuels price, leading to an influx of investors (Denchak). The number of natural gas wells in the U.S. doubled from 2000 to 2010 and has continued growing over the last decade (“Fracking in the United States”). This is evident in the U.S. jumping from third in global oil production ten years ago to first, all while increasing natural gas production by another two-thirds (Elliot and Santiago).

Despite the fracking boom in the United States and the continued use of fossil fuels throughout the world, it is understood that such resources are finite. Estimates on when non-renewable resources will eventually run out are complex and lead to widespread disagreement. Though there is no universally accepted timeline for how long fossil fuels can be sustained, it is generally agreed that natural gas and coal reserves will hold out longer than oil. This consensus gives little assurance, however, as the timeline for natural gas ranges from 50 years to upwards of 350 years (Lorenz). Thus, the question is not whether the United States should transition towards renewable resources; it is simply how soon and how aggressively this transition should take place.

The fracking industry is deeply intertwined with the United States economy. At the height of the fracking boom in 2015, the natural gas and oil industry was credited with supporting 10.3 million jobs, as well as $714 billion in labor income and $1.3 trillion in economic benefit. This accounted for 7.6 percent of the total United States GDP (“Hydraulic Fracturing”). The benefits of this economic impact extend far beyond the states historically credited with the production of oil and natural gas, however, as all fifty states were shown to experience residual benefits (Fleisher). Perhaps the most pervasive of such benefits has been the lowering of gas and energy prices nationwide. A 2019 study found that motor fuel in the United States would cost 43 percent more in the absence of fracking, while electrical prices would cost 31 percent more (Fleisher). Such a decrease in gas prices has similarly affected gas-consuming households. From 2007 to 2013, the increase in fracking saw consumer gas bills drop by $13 billion annually. This total indicates an average saving of $200 per gas-consuming household per year. Moreover, other energy sectors, including commercial, industrial, and electric power consumers, witnessed economic gains totaling $74 billion per year (Fleisher).

Equally indicative of fracking’s role in the U.S. economy is its dominance over the energy sector and its creation of jobs. 2019 marked the first year since 1957 where the United States energy production exceeded consumption, with total production increasing by six percent (“U.S. Energy Facts”). Natural gas and oil are largely responsible for this feat, as they make up 34.7% and 23.6% of the U.S.’s energy industry, respectively. Due to the fact that fracking is responsible for two-thirds of natural gas and 59% of crude oil produced, the fracking industry makes up just under 40% of the total United States energy industry (“U.S. Energy Facts”). Such pervasiveness has led to the shale energy sector (fracking) supporting approximately 9.8 million jobs. This makes up 5.6% of the total U.S. employment pool (Wissman). Moreover, the development of U.S. natural gas reserves is expected to create upwards of one million jobs in the manufacturing industry by 2025. The global hydraulic fracturing market is expected to see even greater rates of growth, as statistics on the growth of fracking suggest that the natural gas market will reach $68 billion dollars by 2024 (“Hydraulic Fracturing Market”). Such a projected leap from the $37.23 billion market value in 2018 is reminiscent of the fracking boom in the early 2010s, giving even more value to the already instrumental fracking industry.

The advent of fracking has also had major economic impacts on a local scale. Fracking has been primarily an industry of the Great Plains region into southern Texas and an area known as the Marcellus Shale, which stretches along the Appalachians from central New York south into Ohio and Virginia. These regions—especially the Marcellus Shale, which has been dubbed the “Saudi Arabia of natural gas”—have seen local communities lifted by the economic benefits of natural gas wells. A study by researchers at the University of Chicago concluded that the shale boom produced benefits to nearby communities valued at $1,900-a-year for the average household (Handy). The same research found that there was an increase in income, employment, and housing prices. On average, employment climbed by 10%, income by 7%, and home prices by 6% in these communities—though in North Dakota, home prices rose an average of 20%, showing the potential economic explosion fracking can cause in communities. These results are validated by another study, which found that fracked communities saw similar increases in employment (3.7–5.5%), income (3.3-6.1%), and housing prices (5.7%). They also found that the average salary increased from anywhere between 5.4 and 11% (Fleisher). Even when the tradeoffs associated with living near natural gas wells are accounted for, nearby communities see benefits of tens of thousands of dollars.

The ingrained nature of fracking in the U.S. energy industry means its removal would devastate the nation’s economy. Naturally, a fracking ban would greatly increase the cost of natural gas and electricity. A report by the Department of Energy estimated that a ban on fracking in the U.S. would increase retail natural gas costs by more than $400 billion between 2021 and 2025, and retail electrical prices by more than $480 billion. The same report calculated the probable price increase which gasoline and diesel fuels would experience. They found there would be an annual price increase by over 100% for gasoline, bringing prices to over $4.20 per gallon in 2022 and 2023. Similarly, the annual average diesel fuel price would increase by 95%, bringing the cost to $4.56 per gallon in 2022 (“Department of Energy”). Cumulatively, the costs associated with a fracking ban could lead to a $7.1 trillion hit to the GDP by 2030. A report to the President in 2021 warned that the elimination of the industry would lead to a loss of 7.7 million jobs in 2022, which would make up 5% of the total American workforce ( Economic and National Security ). An additional report by the U.S. Chamber of Commerce found that the average American family could see their cost-of-living rise by roughly $4,000 (“New Energy Institute Report”). Such consequences would ravage the United States economy, likely triggering another recession.

Not only does the hydraulic fracking industry hold the United States economy together, but it serves as a safeguard against the risks associated with the global energy market. Recent years have seen the United States achieve complete energy security, a feat that has been the goal of Administrations since the 1970’s energy crisis. This means that the U.S. is able to export more energy than it imports, freeing us from reliance on foreign countries for energy, such as Russia and Saudi Arabia. The strength of U.S. oil and natural gas production has made the U.S. far less vulnerable to global oil price shocks, giving domestic consumers reliable and affordable power ( Economic and National Security ). As put by U.S. Representative Fred Keller, “The less reliant the United States and our allies are on energy resources produced by countries that hate us, the less influence they have over us” (“Fracking—Top 3”). Without energy independence, the U.S.’s national security is at risk. Such vulnerability can be seen by our national security assets’ reliance on hydrocarbons to fuel the majority of our military and its operations. This makes a steady supply of fuel necessary to effectively operate our nation’s military. In addition to this, there are several potential chokepoints along international shipping lanes that could be used to cut off fuel supplies to the United States in times of conflict. While a conflict of such magnitude seems farfetched in today’s world, a reliance on foreign energy supplies nonetheless poses a threat to our military security. A more common threat energy reliance poses is foreign countries’ ability to influence our economy. An example of this is the 1973 OAPEC oil embargo, which led to oil shortages and extreme prices, resulting in the 1970’s energy crisis and limited economic growth ( Economic and National Security ). In short, a ban on fracking would put the U.S. economy in the hands of foreign nations.

Though the end of fossil fuels is inevitable, natural gas is a necessary component in the transition to clean energy. The role of natural gas as a “transition fuel” comes as a result of its relatively clean nature in comparison to coal and petroleum. Natural gas has been shown to produce 50% to 60% fewer carbon emissions than coal while generating the same amount of energy. Similarly, it has been shown to give off 30% less CO2 than oil (Wissman). The replacement of coal and petroleum with natural gas has allowed the United States to achieve immediate reductions in greenhouse gases while renewable energy sectors such as wind and solar are built into viable industries (“Fracking—Top 3”). In the last decade, the switching from coal and petroleum to natural gas has eliminated approximately 500 million tons of CO2 emissions from our nation's carbon footprint (“The Role of Gas”).

Despite the environmental benefits of natural gas, the process of hydraulic fracking has been criticized as a danger to the environment and individual health. Opponents of fracking point to the large number of chemicals used in well fluid as a potential danger to local water supplies and overall health. Such concern is due to the fact that, assuming each mixture is approximately 1% chemical additives, over 70,000 gallons of chemicals are required per well. A study by Yale Public Health found that over 80% of such chemicals had never been reviewed by the International Agency for Research on Cancer. Out of those that had been reviewed, 55 were found to be carcinogenic (Pokladnik). These chemicals, which pose the risk of becoming airborne during the fracking process, could contribute to immediate and long-term health issues for nearby communities, according to a study from Colorado School of Public Health (qtd. in Lallanilla). Such additives also present the danger of leaking into local water supplies. In 2012, for example, Chesapeake Energy Corp. was cited with contaminating the drinking water of three families, resulting in a $1.6 settlement (Lallanilla). On a larger scale, the process of fracking has been known to inadvertently release methane, a greenhouse gas known to be 80% to 90% more potent than CO2. Some fracking wells may have methane leakage rates as high as 7.9%, which would outweigh the benefits of using natural gas and make the process of fracking worse than coal (“Fracking”). The uncertainty that characterizes both the chemicals used in fracking and those leaked from it make it easy to see why the process has been criticized by environmentalists.

The use of natural gas as a bridge fuel to renewable energy has also come under fire from climate change advocates. According to thousands of scientists at the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, there is no scenario in which the world can continue digging for fossil fuels, including natural gas obtained from fracking, without causing irreversible damage to the climate (Stein). Research published by the Stockholm Environment Institute reveals that, despite the rhetoric about moving towards renewable energy, the world is on pace to produce 120 % more fossil fuels than would limit global warming to 1.5-degrees Celsius, the goal set by the Paris Agreement in 2015 (Stein). An article by Green America confirms the futility in using natural gas as a transition fuel, stating “The money spent on natural gas power facilities and infrastructure takes decades to recuperate. Companies would need to use these facilities for their full lifetimes, delaying the switch to renewables for far too long” (“Natural Gas: The Myth”). In summary, opponents of fracking argue that a transition fuel is both a futile combatant against climate change and an ideological fantasy which cannot be realistically applied in the industrial world.

Fracking’s role in the United States’s natural security has received similar scrutiny. Many point to the futility in staking energy independence on a resource that is doomed to run out. Due to the fact that fossil fuels are expected to last the U.S. a few more hundred years, at best, 100% renewable energy is the only means by which to obtain long-term energy security. Recent shifts in the global economy due to the COVID-19 pandemic have also highlighted the nature of natural gas as a market-dependent resource, as total demand for fossil fuels dropped 6% in 2020. The only energy industry that experienced growth during this period was renewable, demonstrating its value as the energy of the future (“Fracking—Top 3”).

In light of both the benefits and detriments of hydraulic fracking, I believe the industry should be gradually reduced in favor of renewable resources, though it cannot be completely removed from the energy and economic plan for many years. This is largely because the renewable energy sector is not viable enough to fill the shoes of fracking if eliminated.

Firstly, the economic impact of a fracking ban would far outweigh any progress made towards combating climate change. The economic decline that would occur in the absence of fracking would have great implications for all U.S. citizens, most likely sending us into another recession, if not a depression. Such an economic hit would not only have a negative impact on the lives of almost all Americans, but it would leave the U.S. economy and investors with even less capital to invest in the development of the renewable energy industry. Therefore, the elimination of fracking in the U.S. would have little, if any, immediate impact on improving the strength of the renewable energy sector, all while ravaging the economy.

Perhaps most important in my claim against an immediate ban on fracking is the fact that such a policy would have an overall negative impact on the environment. While a fracking ban would eventually lead to growth and development in the renewable energy industry (after an economic recovery), clean energy would, for many years, be incapable of providing energy for all of America. Thus, the United States would resort to coal, petroleum, and other fossil fuels for energy. This increased usage of “dirtier” energies to compensate for the loss of natural gas would greatly increase the amount of CO2 released in our nation for years to come; optimistic predictions dismiss the possibility of renewable energy being viable any time before 2050 (Roberts). This implies that the United States will also not be able to pin our nation's national security on fossil fuels until at least 2050. The timetable for when the renewable energy sector would become viable is far too long for the U.S. military and government to remain dependent on foreign nations for energy imports. In the long run, while energy security based on renewables is the most ideal, its immediate consequences pose far too great a risk to our national security.

The conversation concerning fracking, in recent years, has become increasingly synonymous with that concerning climate change. While fracking undoubtedly impacts the environment, the question of whether to eliminate the practice is far more nuanced than the general public knows. By backing the argument that fracking cannot be removed from our nation for many years, I am not simply placing the economic prosperity of our nation above the ecological integrity of our planet. Rather, I am asserting that the economic, ecological, and political consequences of such a policy outweigh the benefits. A ban on fracking would have immediate negative implications for our economy, environment, and national security. However, this does not mean that it should never be phased out, as the move to 100 % renewable energy is necessary to avoid irreversible damage to our climate. Such a stance is rarely announced in the polarizing atmosphere of today’s world, and it is one that I feel must be considered if we are to properly address an issue which has such significant implications for our nation's future.

Works Cited

Denchak, Melissa. “Fracking 101.” NRDC , 19 April, 2019, https://www.nrdc.org/stories/fracking-101 . Accessed 21 Nov. 2021.

“Department of Energy Releases Report on Economic and National Security Impacts of a Hydraulic Fracturing Ban.” Office of Fossil Energy and Carbon Management, Energy.Gov , 14 Jan. 2021, https://www.energy.gov/fecm/articles/department-energy-releases-report-economic-and-national-security-impacts-hydraulic . Accessed 21 Nov. 2021.

Economic and National Security Impacts under a Hydraulic Fracturing Ban . U.S. Department of Energy, Jan. 2021, https://www.energy.gov/sites/prod/files/2021/01/f82/economic-and-national-security-impacts-under-a-hydraulic-fracturing-ban.pdf .

Elliott, Rebecca and Luis Santiago. “A Decade in which Fracking Rocked the Oil World.” The Wall Street Journal , 17 Dec. 2019, https://www.wsj.com/articles/a-decade-in-which-fracking-rocked-the-oil-world-11576630807 . Accessed 21 Nov. 2021.

Fleisher, Chris. “Weighing the Impacts of Fracking.” American Economic Association , https://www.aeaweb.org/research/fracking-shale-local-impact-net . Accessed 21 Nov. 2021.

“Fracking.” Center for Biological Diversity , https://www.biologicaldiversity.org/campaigns/fracking/ . Accessed 21 Nov. 2021.

“Fracking—Top 3 Pros and Cons.” ProCon.Org , Britannica, 21 Jan 2022, https://www.procon.org/headlines/fracking-top-3-pros-and-cons/ . Accessed 11 May 2022.

“Fracking in the United States.” Ballotpedia , https://ballotpedia.org/Fracking_in_the_United_States . Accessed 21 Nov. 2021.

Handy, Ryan Maye. “Overall, Fracking Benefits Nearby Communities, Study Finds.” Houston Chronicle , 23 Dec. 2016, https://www.houstonchronicle.com/business/article/Overall-fracking-benefits-nearby-communities-10814313.php .

“Hydraulic Fracturing: Better for the Environment and the Economy.” American Petroleum Institute, https://www.api.org/-/media/Files/Oil-and-Natural-Gas/Hydraulic-Fracturing/Environment-Economic-Benefits/API_FrackingBenefits_FINAL_.pdf .

“Hydraulic Fracturing Market Worth $71.72 Billion by 2026, at 8.69% CAGR; Increasing Demand for Energy Worldwide to Augment Growth: Fortune Business Insights TM .” Fortune Business Insights , Global Newswire, 24 Jan. 2020, https://www.globenewswire.com/en/news-release/2020/01/24/1974749/0/en/Hydraulic-Fracturing-Market-Worth-71-72-Billion-by-2026-at-8-69-CAGR-Increasing-Demand-for-Energy-Worldwide-to-Augment-Growth-Fortune-Business-Insights.html .

Lallanilla, Marc. “Facts About Fracking.” LiveScience 09 Feb. 2018, https://www.livescience.com/34464-what-is-fracking.html . Accessed 11 May 2022.

Lorenz, Ama. “When Will Fossil Fuels Run Out?” FairPlanet , 5 May 2020, https://www.fairplanet.org/story/when-will-fossil-fuels-run-out/ . Accessed 21 Nov. 2021.

“Natural Gas: The Myth of Transition Fuels.” Green America , https://www.greenamerica.org/fight-dirty-energy/amazon-build-cleaner-cloud/natural-gas-transition-fuel-myth . Accessed 21 Nov. 2021.

‘Natural Gas vs. Coal – a Positive Impact on the Environment’. GASVESSEL , 24 Sept. 2018, https://www.gasvessel.eu/news/natural-gas-vs-coal-impact-on-the-environment/ .

“New Energy Institute Report Finds That U.S. Could Lose Nearly 15 Million Jobs If Hydraulic Fracturing Is Banned,” Global Energy Institute , U.S. Chamber of Commerce, 4 Nov. 2016, https://www.globalenergyinstitute.org/new-energy-institute-report-finds-us-could-lose-nearly-15-million-jobs-if-hydraulic-fracturing . Accessed 21 Nov. 2021.

Pokladnik, Randi. “Op-Ed: A Fact-Based Conversation about Fracking.” The Parkersburg News and Sentinel , 31 Oct. 2020, https://www.newsandsentinel.com/opinion/local-columns/2020/10/op-ed-a-fact-based-conversation-about-fracking/ . Accessed 21 Nov. 2021.

PricewaterhouseCoopers. “Impacts of the Natural Gas and Oil Industry on the U.S. Economy in 2015.” https://www.api.org/-/media/Files/Policy/Jobs/National-Factsheet.pdf?la=en&hash=E22F58E3D724DC9D8D7EF76BE86BC3FC953588D5 .

Roberts, David. “Is 100% Renewable Energy Realistic? Here’s What We Know.” Vox , 7 Apr. 2017, https://www.vox.com/energy-and-environment/2017/4/7/15159034/100-renewable-energy-studies .

“The Role of Gas in Today’s Energy Transitions—Analysis.” IEA , July 2019, https://www.iea.org/reports/the-role-of-gas-in-todays-energy-transitions . Accessed 21 Nov. 2021.

Stein, Mark. “Climate and Energy Experts Debate How to Respond to a Warming World.” The New York Times , 7 Oct. 2019, https://www.nytimes.com/2019/10/07/business/energy-environment/climate-energy-experts-debate.html .

“U.S. Energy Facts Explained—Consumption and Production.” EIA—U.S. Energy Information Administration , https://www.eia.gov/energyexplained/us-energy-facts/ . Accessed 21 Nov. 2021.

Wissman, Stephanie Catarino. “Fracking Ban Threatens American Jobs, Derails Environmental Progress.” GoErie , 21 March 2021, https://www.goerie.com/story/opinion/2021/03/26/op-ed-fracking-ban-threatens-jobs-derails-environmental-progress/6986385002/ . Accessed 21 Nov. 2021.

Will Weldon

William Weldon is an Economics major in the College of Arts and Letters who lives in Alumni Hall, the center of the universe. Will is from Upstate New York and grew up in the small town of Cooperstown. Though best known for the Baseball Hall of Fame, Cooperstown, for a period of time, was more focused on protesting the migration of fracking companies into the area than on anything else. The prospect of companies moving into the area and possibly polluting the nearby lake resulted in an abundance of “No Fracking” yard signs and bumper stickers across town. Such controversy sparked Will’s interest and drove him to research the issue for himself. Will looks forward to further pursuing his studies at Notre Dame and would like to thank the Notre Dame community, especially professor Michelle Marvin, for their support.

Science as a Foundation for Policy: The Case of Fracking

Some research on the impacts of hydraulic fracturing, or fracking, on public health has yielded unexpected results — including findings that some expected risks have not materialized. The history of fracking offers important lessons on the proper role of science in environmental policy.

By James Saiers

Note: Yale School of the Environment (YSE) was formerly known as the Yale School of Forestry & Environmental Studies (F&ES). News articles and events posted prior to July 1, 2020 refer to the School's name at that time.

Public perceptions of fracking are shaped by controversies between an industry that has downplayed the risks of fracking and citizens alleging that fracking and attendant activities have polluted air, contaminated drinking water, and scarified landscapes.

Pennsylvania’s Experience: The Good, the Bad, and the Unpleasant

Pennsylvania’s regulatory response, smart management needs good measurements and sound science, can we work together.

Going Forward, Together

When environmental policy builds on careful science, rigorously analyzed data, and solid facts — pursued without fear of upsetting interested parties or overturning prevailing wisdom — innovative solutions often emerge.

- Books / Publications

- Water Resource Science and Management

Connect with us

- Request Information

- Register for Events

The Journal of the NPS Center for Homeland Defense and Security

Fracking: Unintended Consequences for Local Communities

By Chad Stangeland

Chad Stangeland's thesis

– Executive Summary –

After a rise in the global market price of oil and decades-long U.S. reliance on imported oil to meet demands, advancements occurred in the extraction of shale oil. The combination of improvements in hydraulic fracturing, also known as fracking, and the ability to bore wells horizontally created a boom in the energy sector, the epicenter of which was the Bakken shale oil formation in western North Dakota.

Different from conventional oil production, the extraction of oil from shale is known as unconventional oil production, which pumps out a pocket of trapped oil. As with any advancement, its unintended consequences continue to be the subject of research. Since fracking is a relatively new process, speculation and controversy surround it, which inhibits decision makers who must make difficult policy decisions that can have lasting impacts. The primary question asked in this thesis is: What are the effects of unconventional shale oil exploration on local communities?

To answer the research question, this thesis took the form of an analysis of a qualitative case study of the Bakken, the largest shale oil formation in the United States. It includes an identification of causation effects on the local environment, as well as an analysis of the socioeconomic impacts at the local level and their correlation with the boom-and-bust cycle. The case study included the identified environmental concerns of water consumption, groundwater and surface water contamination, handling of produced water, spills, air quality, and seismic activity. The identified socioeconomic concerns comprised the effects of population in-migration, housing demands, economic changes, tax revenues, infrastructure needs, and crime. Based on the data, a qualitative analysis revealed patterns matching previous research, the how and why of events, and trends in the chronology of events.

Oil prices spiking to new highs typically cause a boom: a rapid influx of people looking for high-paying jobs, an abrupt rise in the housing market, income disparity, the displacement of long-time residents, atypical variance in community demographics, an increase in crime, the rapid expansion of infrastructure, an influx of tax revenue, and the deviation of long-term investments from their expected growth pattern. As oil prices drop, the bust ensues: The local economy retracts, causing an increase in local debt. At the time of this writing, the extent of local impacts to the Bakken were emergent.

This research revealed local impacts from unconventional oil production, albeit to varying degrees. Fracking has contributed to the consumption of trillions of gallons of fresh water. Spills have contaminated the soil and surface water with a potential for contaminating groundwater. The release of natural gas has globally polluted air quality. The rapid influx of workers to the area has caused housing prices and crime to rise while many original residents have become either physically or emotionally displaced from their own community. Regardless, fracking has facilitated the creation of new infrastructure in the area.

Six policy and governance recommendations have emerged for decision makers for the prevention of, preparation for, and mitigate of known risks from the findings of this and previous research on fracking. As many long-term impacts remain unknown, the subject of fracking will continue to evolve, resulting in increased clarity. The lessons gained from the case study on the Bakken can frame the discussion and improve decisions for the next community leaders who face the unintended consequences of fracking.

Find all CHDS Theses

Homeland Security Digital Library's Thesis Repository

More Articles

Beyond the Border: The Impact of Flawed Migration Strategies in South and Central America on U.S. Immigration

Do the dutch know much a comparative analysis of gender and use of force in law enforcement in the netherlands and the united states, all hands on deck: a preparedness analysis of municipal fire department mutual aid during fires aboard u.s. navy vessels, legitimation of the police: a practitioner’s framework, 2 thoughts on “fracking: unintended consequences for local communities”.

Fracking is not good!

Thank you Susan, fracking will come to an end because of this comment!

Leave a Comment Cancel Reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

ScholarWorks at University of Montana

- < Previous

Home > Graduate School > Graduate ETDPs > 1053

Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers

The moral layers of fracking: from basic rights and obligations to human flourishing.

Angela L. Hotaling , The University of Montana

Year of Award

Document type, degree type.

Master of Arts (MA)

Degree Name

Department or school/college.

Department of Philosophy

Committee Chair

Albert Borgmann

Commitee Members

Christopher Preston, Daniel Spencer

environmental ethics, environmental justice, fracking, human flourishing

- University of Montana

As it is currently being discussed, hydraulic fracturing or “fracking” is the unconventional method of drilling and extracting oil and natural gas. Fracking starts at the earth’s surface where the technology is created and the sites are constructed. The process continues downward: drills pierce thousands of feet vertically and then horizontally underground. Then, millions of gallons of water mixed with sand and chemicals (referred to as “fracking fluid” or “slick water”) are pumped at high pressure through the pipe so as to fracture shale deposits and release gas or oil. Whether to allow fracking and its associated industrial activity is a complex and heated controversy. The mainstream positions on the issue are typically divided between concerns for the environment and the economy. My subsequent argument against fracking moves beyond both of these mainstream positions. The following argument against fracking is moral and moves in the opposite direction than fracking; it starts from the bottom and moves upward. At the bottom layer, I point out that fracking violates necessary obligations of environmental justice. At the middle layer, I claim, fracking threatens local moral solidarity as I conceive it. Finally, at the top layer, I argue fracking collides with the good life and human flourishing. In other words, I claim fracking not only hinders the availability of necessary material goods, like clean water and air, it also significantly impedes human flourishing. Moreover, fracking promotes or propagates a life of consumption that displaces the good life. I argue against fracking because of its insidious and neglected moral implications. The following three chapters are moral layers; starting at my claim that fracking violates necessary obligations of environmental justice and ascending toward the social and then the material conditions of daily life. The layers of the argument are interconnected, just like the layers of the fracking process itself. By shedding light on how fracking impedes the good life I aim to bring attention to the issue in way that is has yet to be assessed.

Recommended Citation

Hotaling, Angela L., "The Moral Layers of Fracking: From Basic Rights and Obligations to Human Flourishing" (2013). Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers . 1053. https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd/1053

Since November 20, 2013

© Copyright 2013 Angela L. Hotaling

Advanced Search

- Notify me via email or RSS

- Collections

- Disciplines

Author Corner

- Submit Research

- Maureen and Mike Mansfield Library

Home | About | FAQ | My Account | Accessibility Statement

Privacy Copyright

About UM | Accessibility | Administration | Contact UM | Directory | Employment | Safety

- Advisory Group

- Visiting Fellows

- Jobs & Fellowships

Themes & Topics

- Electric Power

- Energy Efficiency

- Fossil Fuels

- Transportation

- Renewable Energy

- Climate Economics

- Climate Law & Policy

- Climate Science

- Air Pollution

- Conservation Economics

- Environmental Health

Centers & Initiatives

- Climate Impact Lab

- E&E Lab

- Abrams Environmental Law Clinic

- Air Quality Monitoring and Data Access

- Energy Impact of Russia Crisis

- Build Back Better on Climate

- Climate Public Opinion

- Social Cost of Carbon

- COP28: Insights & Reflections

- India Legislators Program

- U.S. Energy & Climate Roadmap

- Impact Takeaways

- Opinion & Analyses

- Research Highlights

- All Insights

- In the News

- Around Campus

- EPIC Events

- Faculty Workshops

- Conference Series

- EPIC Career Series

- Energy & Climate Club

- Climate and Energy Lunch & Learn

- Search the site Search Submit search terms

- View Facebook profile (opens new window)

- View Twitter profile (opens new window)

The Fracking Debate: The Pros, Cons, and Lessons Learned from the U.S. Energy Boom

- Location : Saieh Hall For Economics Google Map

Fracking, short for hydraulic fracturing, is perhaps the most important innovation in the energy system in the last half century. The technological breakthrough in fracking, combined with directional drilling, has unleashed massive new supplies of shale oil and natural gas, cutting domestic and global energy prices dramatically, improving U.S. energy security and slashing pollution by displacing coal-fired power generation.

Tens of thousands of shale wells have been drilled across the United States over the past few years, making hydraulic fracturing a part of everyday life for many Americans. The widespread nature of the shale business has therefore raised questions about its local impacts. The Energy Policy Institute at the University of Chicago (EPIC) hosted an event on April 17th as part of its Inquiry & Impact Series that explored the costs and benefits of fracking based on recent research pioneered by University of Chicago scholars. The panel included EPIC’s inaugural policy fellows Sue Tierney and Jeff Holmstead and EPIC Director Michael Greenstone , and was moderated by Axios reporter Amy Harder .

The Local Costs & Benefits

Michael Greenstone, the Milton Friedman Professor in Economics, the College, and the Harris School, kicked off the event by presenting a pair of studies he co-authored on the local impacts of shale development and hydraulic fracturing. The first study found that development increases economic activity, employment, income and housing prices, with the average household benefitting by about $2,000 a year net of social costs. However, if additional evidence identified greater or unknown costs, such as health effects, the net benefits would change, Greenstone said.

Since health is such a critical factor, Greenstone decided to dig further by measuring infant health for children born near shale wells. He and his coauthors found that infants born to mothers living up to about 2 miles from a hydraulic fracturing site suffer from poorer health. The largest impacts were to babies born within about a half mile of a site, with those babies being 25 percent more likely to be born at a low birth weight.

Jeff Holmstead, who represents oil and gas companies in his capacity as a partner at Bracewell, LLP, said industry takes local health impacts seriously.

“From the industry perspective, most operators believe they’re better off with reasonable regulations than with no regulation at all, and I think over time we’ve seen more responsible development of shale resources,” said Holmstead, who served as the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency’s (EPA) assistant administrator for air and radiation during the George W. Bush administration.

Sue Tierney, who lives very close to shale development in Colorado, agreed that the large energy companies have improved their practices over the years.

“In the early periods of this shale gas revolution, where there were stealth entries into communities, people didn’t really know who was buying and selling things and for what purposes, and [there were] a lot of bad surprises as a result,” said Tierney, a former assistant secretary for policy at the Department of Energy under President Clinton and a state cabinet officer for environmental affairs for Massachusetts. “I think that is changing, but that left a bad taste in a lot of people’s mouths.”

Further, there are smaller companies that may not operate with the same rigorous practices as the larger companies, Tierney said.

The National Debate

With some communities banning fracking and others embracing it, tensions between its costs and benefits have turned a local issue into a national debate. Some, including former presidential candidate Bernie Sanders, have called for a nationwide ban on fracking.

Tierney, now a consultant at the Analysis Group, said that would be a “terrible idea” because that would mean “coal would come roaring back.”

“It’s not as though, if you ban fracking tomorrow, that you are going to have a step-function increase in renewable energy in a way that could satisfy the nature of energy demand that we have today,” she said. “Renewable energy is already entering the market at a fast pace, and a ban on fracking would make coal more attractive in the marketplace.”

She pointed out a benefit of natural gas that often seems counter-intuitive—its role in a low-carbon future.

“Absent really great storage or other technology, you cannot integrate renewables without natural gas” serving as backup generation, she said.

But that doesn’t mean that fracking shouldn’t be regulated at the federal level, said Tierney, adding that she has little hope there would be any new regulations developed under the current administration—a challenge made more difficult by a plethora of competing state regulations.

“There’s such a history of states’ rights on this. Much of the regulation we see over oil and gas production evolved from the foundation of states’ use of their police powers, rather than federal environmental regulation. That creates a very varied playground in terms of states’ policies and enforcement,” she said. “There’s been resistance to a more standardized process across the states. I do think that there are some things associated with air quality and associated with clean water issues where there are larger spillover effects on different communities.”

Holmstead largely agreed that the federal government should lead on cross-border issues posed by fracking such as air quality and methane emissions. However, states have evolved over the past 40 years to be able to confront environmental issues in oil and gas development and should be responsible for addressing localized issues, he said.

“When it comes to oil and gas development, it’s not true that Texas doesn’t care about environmental issues,” Holmstead said. “They actually have regulators who know a lot about the industry, that are involved in addressing environmental concerns, so I think a lot of it can be done [at the state level].”

How fracking is portrayed in the media has only complicated how fracking is regulated, regardless of what level of government makes the rules.

Harder brought up “Gasland,” a documentary by an anti-fracking activist that Harder said contained inaccuracies but nonetheless stoked anti-fracking sentiment in the United States and beyond. Holmstead said films like Gasland have shifted the industry’s focus from just legal issues and regulations to public relations.

“I think it’s been a challenge, but they’re at least now putting resources in trying to figure out how to better explain what they do and better address some of the concerns that are raised,” he said.

Tierney said films like “Gasland” demonize the issue.

“I think there are legitimate problems associated with local impacts and I think there are tremendous benefits associated with it,” she said. “I just think it’s incredibly complicated, and any time you’ve got a narrative that is just picking and choosing one-sided pieces of it…it’s a real problem.”

Natural Gas & Climate Change

Because of its role in displacing carbon-rich fossil fuels like coal, natural gas plays a major role in national efforts to address climate change. As such, Harder posed the question: Is natural gas a net benefit or net positive for addressing climate change?

Holmstead said it was a net-positive, reiterating its role as a cost-effective replacement for coal-fired power generation that is being retired and as a support mechanism for renewable energy development. Tierney and Greenstone both characterized it as positive in the short term but negative in the long run.

Despite its net-negative impacts on climate change, Greenstone pointed out that climate change isn’t the foremost issue for many around the world.

“If you’re sitting in India or China, it’s the deal of the century,” said Greenstone, who has extensively researched air quality and other issues in those countries.

“In addition to wanting cheap energy…what they really care about is that they can’t breathe,” he said, referring to how the switch from coal to natural gas can significantly reduce air pollution.

Shale development can result in emissions of methane, a potent greenhouse gas. Some methane is intentionally combusted as a byproduct during fracking (a process known as “flaring”), while some can also leak out of the gas distribution system—an issue that is increasingly important as U.S. consumption of natural gas has increased substantially in recent years.

That’s an area in which industry and regulators could work together, Holmstead said.

“Within the industry…there are companies that believe it’s important to have federal regulation,” he said. “They believe that they would be better off in terms of public perception if there is reasonable federal regulation of methane or related emissions.”

“But they won’t advocate for it,” interjected Tierney.

“Actually, some are,” Holmstead said. “But they’re not going to be doing it publicly.”

This event is part of EPIC’s Energy Inquiry & Impact Series, designed to explore the latest energy data coming out of the University of Chicago and their impacts on policy discussions. Cutting-edge findings will serve as the launching pad to frame these deep-dive conversations, as researchers and EPIC policy fellows navigate ways to translate research into solutions.

Participants

Michael Greenstone

Jeff Holmstead

Susan Tierney

Tuesday, april 17, 2018, registration and hosted bar (21+) opens, event begins: welcome and introductions by michael greenstone, panel: amy harder (moderator), greenstone, jeff holmstead and sue tierney, more on this topic, cepa/hea present epa geologist jeffrey mcdonald, life cycle analysis of energy systems using the greet model, advanced biofuels and the midwest market, energy policy workshop 1: what do consumers believe about future gasoline prices, bp global energy outlook to 2030, energy jewel of the caspian sea, a sustainable energy situation, economics, uncertainties and challenges, building the business case for the back-end of the u.s. nuclear fuel cycle, energy policy workshop 3: risk premia on crude oil futures prices, managing the risks of shale gas: identifying a pathway toward responsible development, energy policy workshop 4, suzanne stelmasek, policy analyst and marketing manager, clean energy trust, 2013 midwest energy forum: “rebuilding the u.s. electricity grid”, nyc harris lecture with prof. rosner, booth energy forward 2013, eric masanet: industrial sustainability through supply chain energy management, rol johnson: from muon colliders to accelerator-driven subcritical reactors, energy practicum brown bag, patricia kampling – ceo, alliant energy: generating results in an environmentally conscious world, dimitri kusnezov, department of energy: the science in policy, uchicago community (if applicable)….

- Faculty/Researcher/Staff

- Undergrad Student

- Masters Student

- PhD Student

Interested In…

- General News

- Monthly e-Newsletter

- Student e-Newsletter (weekly)

- Chicago Events

- EPIC-India News & Events

Science Interviews

- Earth Science

- Engineering

Environmental and societal issues in fracking

Interview with , part of the show can fracking calm the energy crisis, shale_gas_sign.

Jasmin Cooper is a research associate at the Sustainable Gas Institute at Imperial College London and is here to divulge a little more detail on the environmental and social consequences of fracking...

Chris - With us now is Jasmine Cooper. Jasmine's a research associate at the Sustainable Gas Institute at Imperial College and is going to shed a bit more light on some of the environmental, but also the social consequences of fracking. Jasmine, first of all, we haven't considered yet the question, of when we burn this gas, does it amount to the same outcome, which is it's still a climate change gas? Will it still lead to greenhouse gas emission changes in the atmosphere, whether it comes out of fracking or comes out of the North Sea from our existing gas fields?

Jasmine - Yeah, Chris, that's a good question. Absolutely. As Andy said, shale gas is exactly the same as the natural gas we get from the North Sea. So when you burn it, you will get CO2 emitted. You also get methane emissions from the different stages of producing it as well.

Chris - And when we go through the process, as Michael just said, we've gotta drill a lot of holes, Andy said, and you then shove stuff down under pressure into the ground in order to prop those small holes open. There's a lot of stuff going in, there's a lot of environmental impact there that is very visible. It's on land, it's near people's homes. Let sort of drill down, excuse the pun, into each of those elements in turn. The environmental contamination in terms of what we put into the ground. Tell us about that. How much of a risk is that judged to be?

Jasmine - Well it depends a lot on whether or not you'll get any seepage from the hydraulic fracturing into any local aquifers or any water bodies. We've had such little drilling activity, it is really difficult to actually try to put a number on whether or not there'll be any risk of water contamination.

Chris - Experiences in other countries? America?

Jasmine - There is some experience of maybe some migration of chemicals that was used in the fracturing fluid as well as some migration of methane into some local water bodies as well. So potentially yes, but it really depends on whether or not you have any water bodies near where you're drilling. So it goes down to a lot of surveying your area really.

Chris - Well one of our listeners got in touch and said, well how does this all get policed in terms of is self-reporting or is there a regulator? Is there an oversight body? What sort of mechanism is in place to keep tabs on this and also to predict in the way you're saying that this might all might not happen.

Jasmine - Well, in the UK it's quite different to the US because things are regulated quite differently there. A lot of it's on the federal scale and different states have different regulations. In the UK there's a lot more regulations and regulatory bodies. So big organisations like the oil and gas authority, BASE, and environment agencies. So they'd be able to regulate and police different environmental aspects.

Chris - But you're saying that because we've not done very much of it, we have not very much experience of it, which makes it a bit of a chicken and egg. Do we have to do it, find out what can go wrong <laugh> to work at what to police? Or is there already a framework for if we do go down this path, this is how we're gonna keep tabs on it?

Jasmine - Unfortunately yes because each shale gas well in each area that you do drill in, it'll be very different to one another. It's not like an IKEA set, we can just follow the instructions <laugh>. So unfortunately you will have to learn as you go along. You can look at the US because they do have the massive scale of shale gas exploration there. So you can look to see if there's any lessons you can learn from them and what to do and what to not do.

Chris - Okay. And in terms of that pollution argument, how significant do we judge that to be? Because that is something that people are extremely vocal about with groundwater contamination, spread of what gets put down into the wells and so on. How much of a threat do we regard that as?

Jasmine - Based on what's happened in the US it's not necessarily contamination from the hydraulic fracturing and then migrations, that would be the biggest threat would be more of the flow back fluid that's produced.

Chris - So what you put down the well is coming back out?

Jasmine - What comes back up, yeah. Because in addition to the chemicals that's in the fracturing fluid, you also get any chemicals and minerals that are within the rock that would've dissolved.

Chris - That they washed out.

Jasmine - Yeah, what is washed out comes back up

Chris - And what can happen to it?

Jasmine - In the UK it was proposed that any flow back fluid that was produced would be sent to wastewater treatment plants to get treated. But there are some issues because of quite a few of the chemicals that get used in the fracturing fluid. So lots of like surfactants that are used to control the viscosity but also chemicals that can come up from the rock. There's some radioactive materials that can also come up. They're not things wastewater treatment plants are designed to treat?

Chris - Not normally, no.

Jasmine - No, just concerns about how they're gonna handle that.

Chris - What sort of volumes are we talking about? Just briefly? I mean what amount of material might the wastewater comprise? Are we talking thousands of gallons, millions of gallons, litres? How many?

Jasmine - Well it depends on the scale but you're looking at hundreds of thousands of cubic metres.

Chris - So huge. This is a significant issue. Yeah, fair enough. Let's consider the sort of social aspects because we've looked at the sort of geological and the environmental and why people therefore might object to them. What about the whole social thing? How receptive are people really to this? Are people saying 'yeah, okay I can see there's an energy crisis, we need to do our bit, it's fine'. Are people saying 'absolutely not over my dead body?'

Jasmine - I think it's an interesting time because obviously we're in a bit of an energy crisis so that might shift people more towards being more accepting of it. But from an environmental side and also from a community side, if you live near a site where they're going to drill, you may not like the idea of earthquakes that you didn't sign up for when you first moved to where you live. And also the increase in traffic and just the general industrialization of what are normally quite rural communities.

Chris - Mm. The Prime Minister was talking to BBC Radio Lancashire recently. They were pressing her on the question of this whole issue of what they are dubbing 'local consent'. Have a listen to this…

<News Clip>

News Reader - Let's talk about local consent right now. What does local consent look like?

Chris - Prime Minister?

Liz Truss - The, the energy secretary will be laying out, uh, in more detail exactly what that looks like. But it does mean making sure there is local support for, for, for going ahead. And I can assure you it sounds like you don't, I can assure -

News Reader - It sounds like you don't know…

<News Clip Ends>

Chris - …What is local consent, Jasmine <laugh>.

Jasmine - So local consent would be having the support and backing of the local communities so that they are on board with the development of shale gas activity in their area and are actively in favour of the development. And there's no local opposition from both the local community but also the local authorities.

Chris - Because I think other members of the conservative party have said, 'well, people who live near, say, the new nuclear power station that's been endorsed on the southeast coast in England should get free electricity.' So is this a sweetener? Are we saying 'okay, people can get free gas <laugh> if you live near a fracking site?' I mean where's this going to end?

Jasmine - I'm not entirely sure because it depends on where you're drilling the gas and what the gas infrastructure is like. So potentially they could get highly subsidised gas if that's something the operator wants to do. But at the same time I think it's quite tricky to try to incentivize our communities by saying give you free energy because to a certain extent that's a bit like trying to bribe them.

Chris - Yeah, it almost sounds like coercion, doesn't it? I mean, are you comfortable with the question of fracking and if, if you were living in this area, would you say, look, knowing what I know, I'm an expert in this area, I'm quite comfortable with it going ahead, please do. Or, or would you actually object?

Jasmine - From a scientific perspective, I find it really interesting, but if I had to live near a site where they're going to drill shale gas, I might be a bit anxious.

Chris - Nuclear power station?

Jasmine - Less anxious.

Chris - Less anxious. That's interesting though, because a lot of people say they would much rather live near a coal fired power station than a nuclear power station. But weight for weight what the coal fired station chucks up the chimney is more radioactive, because of what's coming out of the ground or being burned by the thousands of tonne load. Jasmine, thanks very much. That's Jasmine Cooper. She's from Imperial College.

- Previous The geology of fracking

- Next Cockatoos become bin raiding menace

Related Content

What’s going on in the teenage brain, plant pests drugged by pharmaceuticals in wastewater, bacteria: taking up ancient dna, power to the pollinators - planet earth online, how best to treat child adhd, add a comment, support us, forum discussions.

- Search Search Please fill out this field.

Fracking and Air Quality

Fracking and water quality, fracking and earth and soil quality.

- Fracking FAQs

The Bottom Line

- Fundamental Analysis

- Sectors & Industries

How Does Fracking Affect the Environment?

Fracking can negatively impact air and water quality in fracked areas

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/picture-53894-1440689455-5bfc2a8846e0fb00260af532.jpg)

Pete Rathburn is a copy editor and fact-checker with expertise in economics and personal finance and over twenty years of experience in the classroom.

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/E7F37E3D-4C78-4BDA-9393-6F3C581602EB-2c2c94499d514e079e915307db536454.jpeg)

The U.S. natural gas industry has enjoyed record levels of production in recent years. In 2018, the U.S. became the top producer of oil and natural gas in the world, even beating Saudi Arabia. Although gas production experienced a slight dip at the start of the COVID-19 pandemic, by the end of 2021 natural gas drilling once again reached record highs.

This natural gas boom is largely thanks to hydraulic fracturing , commonly known as fracking , an extraction process that combines chemicals (often toxic ones) with large amounts of water and sand at high pressure to shatter the earth and rocks. Fracking is controversial because of the number of natural resources it uses, and the negative effects it can have on the air and water quality of the fracked areas.

Key Takeaways

- Hydraulic fracturing, or fracking, is a process that uses high-pressure fluid injections to shatter rock formations and extract natural gas.

- Fracking has been blamed for leaking millions of tons of methane, a greenhouse gas more potent than carbon dioxide.

- Fracking is also associated with other airborne hydrocarbons that can cause health and respiratory issues.

- Fracking uses large amounts of water, which can become contaminated and affect local groundwater.

- Moreover, due to the high pressures involved, fracking is also associated with increased seismic activity.

One of the main pollutants released in the fracking process is methane, a greenhouse gas that traps 25 times more heat than carbon dioxide. Research indicates the U.S. oil and gas industry emits 16.9 million metric tons of methane every year, according to the International Energy Agency. Some of this methane is inadvertently leaked through faulty equipment, or deliberately vented into the atmosphere between extractions. The Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) estimates that the U.S. accounts for more methane emissions than 164 countries combined.

In addition to methane, fracking also releases toxic compounds such as nitrogen oxides, benzene, hydrogen sulfide, and other hydrocarbons, forming smog and ozone that can cause health problems to those living nearby. Local air pollution can aggravate asthma and other respiratory conditions.

Fracking fluid is a mix of water, chemicals, and solid particles used to penetrate and fracture underground rock. The EPA has identified over a thousand different chemicals that have been used in fracking fluid, and many are considered harmful to human health. Other ingredients are considered trade secrets and are not revealed to the public.

Fracking uses large amounts of water and releases toxic chemicals into the surrounding water table. Each well consumes a median of 1.5 million gallons, according to the EPA, adding up to billions of gallons nationwide every year. Not only does this reduce the amount of water available for drinking and irrigation, but it also threatens to pollute local sources with contaminated wastewater.

The byproduct of fracking's water consumption is billions of gallons of wastewater that may be contaminated by petrochemicals. The majority is injected into underground wells, and what isn't injected is transported for treatment. The EPA highlights potential leakage from wastewater storage pits, or accidental releases during transport, as risks to drinking water supplies.

In addition to air and water pollution, fracking can have long-term effects on the soil and surrounding vegetation. The high salinity of wastewater spills can reduce the soil's ability to support plant life.

Fracking has also been blamed for seismic activity. Following the boom of hydraulic fracturing, the number of tremors has risen dramatically, especially in areas with frequent drilling. Following the completion of drilling operations, the resultant waste fluids are often disposed by injecting them into deep wells, at pressures high enough to cause damaging earthquakes. The largest earthquake attributed to wastewater disposal was an M5.8 Earthquake near Pawnee, Oklahoma.

What Are the Pros and Cons of Fracking?