Pathos Definition

What is pathos? Here’s a quick and simple definition:

Pathos , along with logos and ethos , is one of the three "modes of persuasion" in rhetoric (the art of effective speaking or writing). Pathos is an argument that appeals to an audience's emotions. When a speaker tells a personal story, presents an audience with a powerful visual image, or appeals to an audience's sense of duty or purpose in order to influence listeners' emotions in favor of adopting the speaker's point of view, he or she is using pathos .

Some additional key details about pathos:

- You may also hear the word "pathos" used to mean "a quality that invokes sadness or pity," as in the statement, "The actor's performance was full of pathos." However, this guide focuses specifically on the rhetorical technique of pathos used in literature and public speaking to persuade readers and listeners through an appeal to emotion.

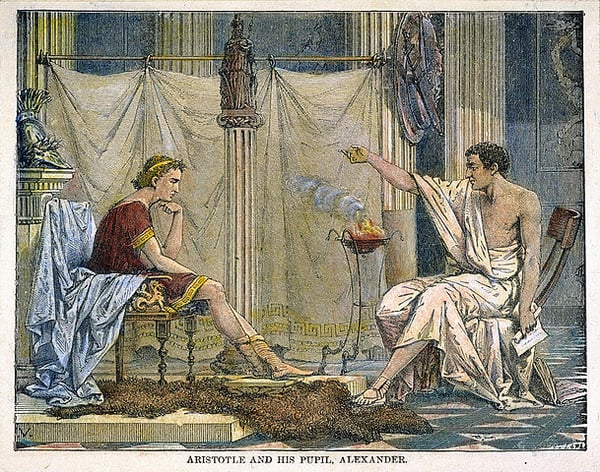

- The three "modes of persuasion"— pathos , logos , and ethos —were originally defined by Aristotle.

- In contrast to pathos, which appeals to the listener's emotions, logos appeals to the audience's sense of reason, while ethos appeals to the audience based on the speaker's authority.

- Although Aristotle developed the concept of pathos in the context of oratory and speechmaking, authors, poets, and advertisers also use pathos frequently.

Pathos Pronunciation

Here's how to pronounce pathos : pay -thos

Pathos in Depth

Aristotle (the ancient Greek philosopher and scientist) first defined pathos , along with logos and ethos , in his treatise on rhetoric, Ars Rhetorica. Together, he referred to pathos , logos , and ethos as the three modes of persuasion, or sometimes simply as "the appeals." Aristotle defined pathos as "putting the audience in a certain frame of mind," and argued that to achieve this task a speaker must truly know and understand his or her audience. For instance, in Ars Rhetorica, Aristotle describes the information a speaker needs to rile up a feeling of anger in his or her audience:

Take, for instance, the emotion of anger: here we must discover (1) what the state of mind of angry people is, (2) who the people are with whom they usually get angry, and (3) on what grounds they get angry with them. It is not enough to know one or even two of these points; unless we know all three, we shall be unable to arouse anger in any one.

Here, Aristotle articulates that it's not enough to know the dominant emotions that move one's listeners: you also need to have a deeper understanding of the listeners' values, and how these values motivate their emotional responses to specific individuals and behaviors.

Pathos vs Logos and Ethos

Pathos is often criticized as being the least substantial or legitimate of the three persuasive modest. Arguments using logos appeal to listeners' sense of reason through the presentation of facts and a well-structured argument. Meanwhile, arguments using ethos generally try to achieve credibility by relying on the speaker's credentials and reputation. Therefore, both logos and ethos may seem more concrete—in the sense of being more evidence-based—than pathos, which "merely" appeals to listeners' emotions. But people often forget that facts, statistics, credentials, and personal history can be easily manipulated or fabricated in order to win the confidence of an audience, while people at the same time underestimate the power and importance of being able to expertly direct the emotional current of an audience to win their allegiance or sympathy.

Pathos Examples

Pathos in literature.

Characters in literature often use pathos to convince one another, or themselves, of a certain viewpoint. It's important to remember that pathos , perhaps more than the other modes of persuasion, relies not only on the content of what is said, but also on the tone and expressiveness of the delivery . For that reason, depictions of characters using pathos can be dramatic and revealing of character.

Pathos in Jane Austen's Pride and Prejudice

In this example from Chapter 16 of Pride and Prejudice , George Wickham describes the history of his relationship with Mr. Darcy to Elizabeth Bennet—or at least, he describes his version of their shared history. Wickham's goal is to endear himself to Elizabeth, turn her against Mr. Darcy, and cover up the truth. (Wickham actually squanders his inheritance from Mr. Darcy's father and, out of laziness, turns down Darcy Senior's offer help him obtain a "living" as a clergyman.)

"The church ought to have been my profession...had it pleased [Mr. Darcy]... Yes—the late Mr. Darcy bequeathed me the next presentation of the best living in his gift. He was my godfather, and excessively attached to me. I cannot do justice to his kindness. He meant to provide for me amply, and thought he had done it; but when the living fell it was given elsewhere...There was just such an informality in the terms of the bequest as to give me no hope from law. A man of honor could not have doubted the intention, but Mr. Darcy chose to doubt it—or to treat it as a merely conditional recommendation, and to assert that I had forfeited all claim to it by extravagance, imprudence, in short any thing or nothing. Certain it is, that the living became vacant two years ago, exactly as I was of an age to hold it, and that it was given to another man; and no less certain is it, that I cannot accuse myself of having really done anything to deserve to lose it. I have a warm, unguarded temper, and I may perhaps have sometimes spoken my opinion of him, and to him, too freely. I can recall nothing worse. But the fact is, that we are very different sort of men, and that he hates me." "This is quite shocking!—he deserves to be publicly disgraced." "Some time or other he will be—but it shall not be by me. Till I can forget his father, I can never defy or expose him." Elizabeth honored him for such feelings, and thought him handsomer than ever as he expressed them.

Here, Wickham claims that Darcy robbed him of his intended profession out of greed, and that he, Wickham, is too virtuous to reveal Mr. Darcy's "true" nature with respect to this issue. By doing so, Wickham successfully uses pathos in the form of a personal story, inspiring Elizabeth to feel sympathy, admiration, and romantic interest towards him. In this example, Wickham's use of pathos indicates a shifty, manipulative character and lack of substance.

Pathos in Nathaniel Hawthorne's The Scarlet Letter

In The Scarlet Letter , Hawthorne tells the story of Hester Prynne, a young woman living in seventeenth-century Boston. As punishment for committing the sin of adultery, she is sentenced to public humiliation on the scaffold, and forced to wear the scarlet letter "A" on her clothing for the rest of her life. Even though Hester's punishment exposes her before the community, she refuses to reveal the identity of the man she slept with. In the following passage from Chapter 3, two reverends—first, Arthur Dimmesdale and then John Wilson—urge her to reveal the name of her partner:

"What can thy silence do for him, except it tempt him—yea, compel him, as it were—to add hypocrisy to sin? Heaven hath granted thee an open ignominy, that thereby thou mayest work out an open triumph over the evil within thee and the sorrow without. Take heed how thou deniest to him—who, perchance, hath not the courage to grasp it for himself—the bitter, but wholesome, cup that is now presented to thy lips!’ The young pastor’s voice was tremulously sweet, rich, deep, and broken. The feeling that it so evidently manifested, rather than the direct purport of the words, caused it to vibrate within all hearts, and brought the listeners into one accord of sympathy. Even the poor baby at Hester’s bosom was affected by the same influence, for it directed its hitherto vacant gaze towards Mr. Dimmesdale, and held up its little arms with a half-pleased, half-plaintive murmur... "Woman, transgress not beyond the limits of Heaven’s mercy!’ cried the Reverend Mr. Wilson, more harshly than before. ‘That little babe hath been gifted with a voice, to second and confirm the counsel which thou hast heard. Speak out the name! That, and thy repentance, may avail to take the scarlet letter off thy breast."

The reverends call upon Hester's love for the father of her child—the same love they are condemning—to convince her to reveal his identity. Their attempts to move her by appealing to her sense of duty, compassion and morality are examples of pathos. Once again, this example of pathos reveals a lack of moral fiber in the reverends who are attempting to manipulate Hester by appealing to her emotions, particularly since (spoiler alert!) Reverend Dimmesdale is in fact the father.

Pathos in Dylan Thomas' "Do Not Go Gentle Into That Good Night"

In " Do Not Go Gentle Into That Good Night," Thomas urges his dying father to cling to life and his love of it. The poem is a villanelle , a specific form of verse that originated as a ballad or "country song" and is known for its repetition. Thomas' selection of the repetitive villanelle form contributes to the pathos of his insistent message to his father—his appeal to his father's inner strength:

Do not go gentle into that good night, Old age should burn and rave at close of day; Rage, rage against the dying of the light. Though wise men at their end know dark is right, Because their words had forked no lightning they Do not go gentle into that good night. Good men, the last wave by, crying how bright Their frail deeds might have danced in a green bay, Rage, rage against the dying of the light. Wild men who caught and sang the sun in flight, And learn, too late, they grieved it on its way, Do not go gentle into that good night. Grave men, near death, who see with blinding sight Blind eyes could blaze like meteors and be gay, Rage, rage against the dying of the light.

It's worth noting that, in this poem, pathos is not in any way connected to a lack of morals or inner strength. Quite the opposite, the appeal to emotion is connected to a profound love—the poet's own love for his father.

Pathos in Political Speeches

Politicians understand the power of emotion, and successful politicians are adept at harnessing people's emotions to curry favor for themselves, as well as their policies and ideologies.

Pathos in Barack Obama's 2013 Address to the Nation on Syria

In August 2013, the Syrian government, led by Bashar al-Assad, used chemical weapons against Syrians who opposed his regime, causing several countries—including the United States—to consider military intervention in the conflict. Obama's tragic descriptions of civilians who died as a result of the attack are an example of pathos : they provoke an emotional response and help him mobilize American sentiment in favor of U.S. intervention.

Over the past two years, what began as a series of peaceful protests against the oppressive regime of Bashar al-Assad has turned into a brutal civil war. Over 100,000 people have been killed. Millions have fled the country...The situation profoundly changed, though, on August 21st, when Assad’s government gassed to death over 1,000 people, including hundreds of children. The images from this massacre are sickening: men, women, children lying in rows, killed by poison gas, others foaming at the mouth, gasping for breath, a father clutching his dead children, imploring them to get up and walk.

Pathos in Ronald Reagan's 1987 " Tear Down This Wall!" Speech

In 1987, the Berlin Wall divided Communist East Berlin from Democratic West Berlin. The Wall was a symbol of the divide between the communist Soviet Union, or Eastern Bloc, and the Western Bloc which included the United States, NATO and its allies. The wall also split Berlin in two, obstructing one of Berlin's most famous landmarks: the Brandenburg Gate.

Reagan's speech, delivered to a crowd in front of the Brandenburg Gate, contains many examples of pathos:

Behind me stands a wall that encircles the free sectors of this city, part of a vast system of barriers that divides the entire continent of Europe...Yet it is here in Berlin where the wall emerges most clearly...Every man is a Berliner, forced to look upon a scar... General Secretary Gorbachev, if you seek peace, if you seek prosperity for the Soviet Union and Eastern Europe, if you seek liberalization: Come here to this gate! Mr. Gorbachev, open this gate! Mr. Gorbachev, tear down this wall!

Reagan moves his listeners to feel outrage at the Wall's existence by calling it a "scar." He assures Germans that the world is invested in the city's problems by telling the crowd that "Every man is a Berliner." Finally, he excites and invigorates the listener by boldly daring Gorbachev, president of the Soviet Union, to "tear down this wall!"

Pathos in Advertising

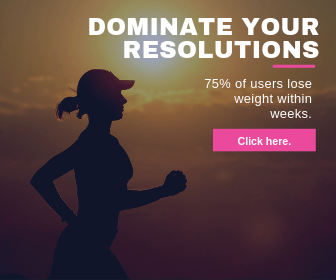

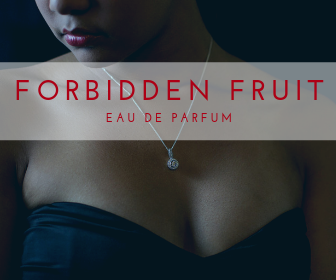

Few appreciate the complexity of pathos better than advertisers. Consider all the ads you've seen in the past week. Whether you're thinking of billboards, magazine ads, or TV commercials, its almost a guarantee that the ones you remember contained very little specific information about the product, and were instead designed to create an emotional association with the brand. Advertisers spend incredible amounts of money trying to understand exactly what Aristotle describes as the building blocks of pathos: the emotional "who, what, and why" of their target audience. Take a look at this advertisement for the watch company, Rolex, featuring David Beckham:

Notice that the ad doesn't convey anything specific about the watch itself to make someone think it's a high quality or useful product. Instead, the ad caters to Rolex's target audience of successful male professionals by causing them to associate the Rolex brand with soccer player David Beckham, a celebrity who embodies the values of the advertisement's target audience: physical fitness and attractiveness, style, charisma, and good hair.

Why Do Writers Use Pathos?

The philosopher and psychologist William James once said, “The emotions aren’t always immediately subject to reason, but they are always immediately subject to action.” Pathos is a powerful tool, enabling speakers to galvanize their listeners into action, or persuade them to support a desired cause. Speechwriters, politicians, and advertisers use pathos for precisely this reason: to influence their audience to a desired belief or action.

The use of pathos in literature is often different than in public speeches, since it's less common for authors to try to directly influence their readers in the way politicians might try to influence their audiences. Rather, authors often employ pathos by having a character make use of it in their own speech. In doing so, the author may be giving the reader some insight into a character's values, motives, or their perception of another character.

Consider the above example from The Scarlet Letter. The clergymen in Hester's town punish her by publicly humiliating her in front of the community and holding her up as an example of sin for conceiving a child outside of marriage. The reverends make an effort to get Hester to tell them the name of her child's father by making a dramatic appeal to a sense of shame that Hester plainly does not feel over her sin. As a result, this use of pathos only serves to expose the the manipulative intent of the reverends, offering readers some insight into their moral character as well as that of Puritan society at large. Ultimately, it's a good example of an ineffective use of pathos , since what the reverends lack is the key to eliciting the response they want: a strong grasp of what their listener values.

Other Helpful Pathos Resources

- The Wikipedia Page on Pathos: A detailed explanation which covers Aristotle's original ideas on pathos and discusses how the term's meaning has changed over time.

- The Dictionary Definition of Pathos: A definition and etymology of the term, which comes from the Greek pàthos, meaning "suffering or sensation."

- An excellent video from TED-Ed about the three modes of persuasion.

- A pathos -laden recording of Dylan Thomas reading his poem "Do Not Go Gentle Into That Good Night"

- PDFs for all 136 Lit Terms we cover

- Downloads of 1944 LitCharts Lit Guides

- Teacher Editions for every Lit Guide

- Explanations and citation info for 40,985 quotes across 1944 books

- Downloadable (PDF) line-by-line translations of every Shakespeare play

- Understatement

- Blank Verse

- Falling Action

- Parallelism

- Verbal Irony

- Anachronism

- Red Herring

- Tragic Hero

- Climax (Figure of Speech)

- Static Character

Definition of Pathos

No man is an island, Entire of itself, Every man is a piece of the continent, A part of the main. If a clod be washed away by the sea, Europe is the less. As well as if a promontory were. As well as if a manor of thy friend’s Or of thine own were: Any man’s death diminishes me, Because I am involved in mankind, And therefore never send to know for whom the bell tolls ; It tolls for thee.

By describing how all men are connected rather than isolated, Donne utilizes pathos as an emotional appeal to readers of his poem. The feelings evoked by the poet are grief and sympathy for all who die, because all death is an individual loss and a loss for mankind as a whole.

Common Examples of Emotions Evoked by Pathos

Examples of pathos in advertisement, famous examples of pathos in movie lines.

Many films feature dialogue that generates pathos and emotional reactions in viewers. Here are some famous examples of pathos in well-known movie lines:

Difference Between Pathos, Logos, and Ethos

Aristotle outlined three forms of rhetoric, which is the art of effective speaking and writing. These forms are pathos, logos , and ethos . As a matter of rhetorical persuasion, it is important for these forms (or “appeals”) to be balanced. This is especially true for pathos in that overuse of emotional appeal can lead to a flawed argument without the balance of logic or credibility.

Effect of Pathos on Logos

Effect of pathos on ethos.

Although ethos is itself a strong rhetorical device and works wonders when it comes to persuasion and convincing the audience, when a touch of pathos is added to it, it becomes a lethal weapon. It has happened in I Have a Dream , a powerful rhetorical piece of Martin Luther King and the speech is still a memorable rhetorical piece. The reason is that not only does it enhance the power of argument when added with an ethos, it also increases the trust and credibility of the speaker or orator.

How To Build Arguments Using Pathos

Fallacy of emotion (pathos) / fallacious pathos, three characteristics of pathos, using pathos in sentences, examples of pathos in literature, example 1: funeral blues by w.h. auden.

He was my North, my South, my East and West, My working week and my Sunday rest, My noon, my midnight, my talk, my song; I thought that love would last forever: I was wrong. The stars are not wanted now ; put out every one, Pack up the moon and dismantle the sun, Pour away the ocean and sweep up the wood; For nothing now can ever come to any good.

Example 2: I Know Why the Caged Bird Sings by Maya Angelou

If growing up is painful for the Southern Black girl, being aware of her displacement is the rust on the razor that threatens the throat. It is an unnecessary insult.

Example 3: Romeo and Juliet by William Shakespeare

Two households, both alike in dignity In fair Verona, where we lay our scene From ancient grudge break to new mutiny Where civil blood makes civil hands unclean. From forth the fatal loins of these two foes A pair of star- cross ’d lovers take their life Whose misadventured piteous overthrows Do with their death bury their parents’ strife.

Synonyms of Pathos

Related posts:, post navigation.

Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, generate accurate citations for free.

- Knowledge Base

- How to write a rhetorical analysis | Key concepts & examples

How to Write a Rhetorical Analysis | Key Concepts & Examples

Published on August 28, 2020 by Jack Caulfield . Revised on July 23, 2023.

A rhetorical analysis is a type of essay that looks at a text in terms of rhetoric. This means it is less concerned with what the author is saying than with how they say it: their goals, techniques, and appeals to the audience.

Instantly correct all language mistakes in your text

Upload your document to correct all your mistakes in minutes

Table of contents

Key concepts in rhetoric, analyzing the text, introducing your rhetorical analysis, the body: doing the analysis, concluding a rhetorical analysis, other interesting articles, frequently asked questions about rhetorical analysis.

Rhetoric, the art of effective speaking and writing, is a subject that trains you to look at texts, arguments and speeches in terms of how they are designed to persuade the audience. This section introduces a few of the key concepts of this field.

Appeals: Logos, ethos, pathos

Appeals are how the author convinces their audience. Three central appeals are discussed in rhetoric, established by the philosopher Aristotle and sometimes called the rhetorical triangle: logos, ethos, and pathos.

Logos , or the logical appeal, refers to the use of reasoned argument to persuade. This is the dominant approach in academic writing , where arguments are built up using reasoning and evidence.

Ethos , or the ethical appeal, involves the author presenting themselves as an authority on their subject. For example, someone making a moral argument might highlight their own morally admirable behavior; someone speaking about a technical subject might present themselves as an expert by mentioning their qualifications.

Pathos , or the pathetic appeal, evokes the audience’s emotions. This might involve speaking in a passionate way, employing vivid imagery, or trying to provoke anger, sympathy, or any other emotional response in the audience.

These three appeals are all treated as integral parts of rhetoric, and a given author may combine all three of them to convince their audience.

Text and context

In rhetoric, a text is not necessarily a piece of writing (though it may be this). A text is whatever piece of communication you are analyzing. This could be, for example, a speech, an advertisement, or a satirical image.

In these cases, your analysis would focus on more than just language—you might look at visual or sonic elements of the text too.

The context is everything surrounding the text: Who is the author (or speaker, designer, etc.)? Who is their (intended or actual) audience? When and where was the text produced, and for what purpose?

Looking at the context can help to inform your rhetorical analysis. For example, Martin Luther King, Jr.’s “I Have a Dream” speech has universal power, but the context of the civil rights movement is an important part of understanding why.

Claims, supports, and warrants

A piece of rhetoric is always making some sort of argument, whether it’s a very clearly defined and logical one (e.g. in a philosophy essay) or one that the reader has to infer (e.g. in a satirical article). These arguments are built up with claims, supports, and warrants.

A claim is the fact or idea the author wants to convince the reader of. An argument might center on a single claim, or be built up out of many. Claims are usually explicitly stated, but they may also just be implied in some kinds of text.

The author uses supports to back up each claim they make. These might range from hard evidence to emotional appeals—anything that is used to convince the reader to accept a claim.

The warrant is the logic or assumption that connects a support with a claim. Outside of quite formal argumentation, the warrant is often unstated—the author assumes their audience will understand the connection without it. But that doesn’t mean you can’t still explore the implicit warrant in these cases.

For example, look at the following statement:

We can see a claim and a support here, but the warrant is implicit. Here, the warrant is the assumption that more likeable candidates would have inspired greater turnout. We might be more or less convinced by the argument depending on whether we think this is a fair assumption.

Here's why students love Scribbr's proofreading services

Discover proofreading & editing

Rhetorical analysis isn’t a matter of choosing concepts in advance and applying them to a text. Instead, it starts with looking at the text in detail and asking the appropriate questions about how it works:

- What is the author’s purpose?

- Do they focus closely on their key claims, or do they discuss various topics?

- What tone do they take—angry or sympathetic? Personal or authoritative? Formal or informal?

- Who seems to be the intended audience? Is this audience likely to be successfully reached and convinced?

- What kinds of evidence are presented?

By asking these questions, you’ll discover the various rhetorical devices the text uses. Don’t feel that you have to cram in every rhetorical term you know—focus on those that are most important to the text.

The following sections show how to write the different parts of a rhetorical analysis.

Like all essays, a rhetorical analysis begins with an introduction . The introduction tells readers what text you’ll be discussing, provides relevant background information, and presents your thesis statement .

Hover over different parts of the example below to see how an introduction works.

Martin Luther King, Jr.’s “I Have a Dream” speech is widely regarded as one of the most important pieces of oratory in American history. Delivered in 1963 to thousands of civil rights activists outside the Lincoln Memorial in Washington, D.C., the speech has come to symbolize the spirit of the civil rights movement and even to function as a major part of the American national myth. This rhetorical analysis argues that King’s assumption of the prophetic voice, amplified by the historic size of his audience, creates a powerful sense of ethos that has retained its inspirational power over the years.

The body of your rhetorical analysis is where you’ll tackle the text directly. It’s often divided into three paragraphs, although it may be more in a longer essay.

Each paragraph should focus on a different element of the text, and they should all contribute to your overall argument for your thesis statement.

Hover over the example to explore how a typical body paragraph is constructed.

King’s speech is infused with prophetic language throughout. Even before the famous “dream” part of the speech, King’s language consistently strikes a prophetic tone. He refers to the Lincoln Memorial as a “hallowed spot” and speaks of rising “from the dark and desolate valley of segregation” to “make justice a reality for all of God’s children.” The assumption of this prophetic voice constitutes the text’s strongest ethical appeal; after linking himself with political figures like Lincoln and the Founding Fathers, King’s ethos adopts a distinctly religious tone, recalling Biblical prophets and preachers of change from across history. This adds significant force to his words; standing before an audience of hundreds of thousands, he states not just what the future should be, but what it will be: “The whirlwinds of revolt will continue to shake the foundations of our nation until the bright day of justice emerges.” This warning is almost apocalyptic in tone, though it concludes with the positive image of the “bright day of justice.” The power of King’s rhetoric thus stems not only from the pathos of his vision of a brighter future, but from the ethos of the prophetic voice he adopts in expressing this vision.

The conclusion of a rhetorical analysis wraps up the essay by restating the main argument and showing how it has been developed by your analysis. It may also try to link the text, and your analysis of it, with broader concerns.

Explore the example below to get a sense of the conclusion.

It is clear from this analysis that the effectiveness of King’s rhetoric stems less from the pathetic appeal of his utopian “dream” than it does from the ethos he carefully constructs to give force to his statements. By framing contemporary upheavals as part of a prophecy whose fulfillment will result in the better future he imagines, King ensures not only the effectiveness of his words in the moment but their continuing resonance today. Even if we have not yet achieved King’s dream, we cannot deny the role his words played in setting us on the path toward it.

If you want to know more about AI tools , college essays , or fallacies make sure to check out some of our other articles with explanations and examples or go directly to our tools!

- Ad hominem fallacy

- Post hoc fallacy

- Appeal to authority fallacy

- False cause fallacy

- Sunk cost fallacy

College essays

- Choosing Essay Topic

- Write a College Essay

- Write a Diversity Essay

- College Essay Format & Structure

- Comparing and Contrasting in an Essay

(AI) Tools

- Grammar Checker

- Paraphrasing Tool

- Text Summarizer

- AI Detector

- Plagiarism Checker

- Citation Generator

The goal of a rhetorical analysis is to explain the effect a piece of writing or oratory has on its audience, how successful it is, and the devices and appeals it uses to achieve its goals.

Unlike a standard argumentative essay , it’s less about taking a position on the arguments presented, and more about exploring how they are constructed.

The term “text” in a rhetorical analysis essay refers to whatever object you’re analyzing. It’s frequently a piece of writing or a speech, but it doesn’t have to be. For example, you could also treat an advertisement or political cartoon as a text.

Logos appeals to the audience’s reason, building up logical arguments . Ethos appeals to the speaker’s status or authority, making the audience more likely to trust them. Pathos appeals to the emotions, trying to make the audience feel angry or sympathetic, for example.

Collectively, these three appeals are sometimes called the rhetorical triangle . They are central to rhetorical analysis , though a piece of rhetoric might not necessarily use all of them.

In rhetorical analysis , a claim is something the author wants the audience to believe. A support is the evidence or appeal they use to convince the reader to believe the claim. A warrant is the (often implicit) assumption that links the support with the claim.

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the “Cite this Scribbr article” button to automatically add the citation to our free Citation Generator.

Caulfield, J. (2023, July 23). How to Write a Rhetorical Analysis | Key Concepts & Examples. Scribbr. Retrieved June 18, 2024, from https://www.scribbr.com/academic-essay/rhetorical-analysis/

Is this article helpful?

Jack Caulfield

Other students also liked, how to write an argumentative essay | examples & tips, how to write a literary analysis essay | a step-by-step guide, comparing and contrasting in an essay | tips & examples, what is your plagiarism score.

- Entertainment

- Environment

- Information Science and Technology

- Social Issues

Home Essay Samples Sociology Rhetorical Strategies

How to Use Pathos in an Essay: Connecting Emotion and Persuasion

Table of contents, the power of pathos, techniques for utilizing pathos, balance and ethical considerations.

- Aristotle. (n.d.). Rhetoric. Project Gutenberg. https://www.gutenberg.org/ebooks/16357

- Edlund, J. R. (2019). The Ethos-Pathos-Logos of Aristotle's Rhetoric. Humanities Commons. https://hcommons.org/deposits/item/hc:24300/

- Perloff, M. (2009). The dynamics of persuasion: Communication and attitudes in the 21st century. Routledge.

- Johnson, R. H. (2005). Imagining the audience in audience appeals: Audience invoked in American public address textbooks, 1830-1930. Rhetoric & Public Affairs, 8(3), 429-453.

- Walton, D. N. (2013). The new dialectic: Conversational contexts of argument. University of Toronto Press.

- Kellner, D. (2009). Critical theory, Marxism, and modernity. In The Routledge companion to social and political philosophy (pp. 381-395). Routledge.

- Gardner, R. C. (2019). Environmental psychology: An introduction. Routledge.

- Pinker, S. (2014). The sense of style: The thinking person's guide to writing in the 21st century. Penguin Books.

- Cialdini, R. B. (2008). Influence: Science and practice (Vol. 4). Pearson Education.

- Sobieraj, S., & Berry, J. M. (2011). From incivility to outrage: Political discourse in blogs, talk radio, and cable news. Political Communication, 28(1), 19-41.

*minimum deadline

Cite this Essay

To export a reference to this article please select a referencing style below

- Generation Gap

- Cell Phones and Driving

- Baby Boomers

- Communication

- Generation X

- Homosexuality

Related Essays

Need writing help?

You can always rely on us no matter what type of paper you need

*No hidden charges

100% Unique Essays

Absolutely Confidential

Money Back Guarantee

By clicking “Send Essay”, you agree to our Terms of service and Privacy statement. We will occasionally send you account related emails

You can also get a UNIQUE essay on this or any other topic

Thank you! We’ll contact you as soon as possible.

Table of Contents

Collaboration, information literacy, writing process, using pathos in persuasive writing.

- CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 by Angela Eward-Mangione - Hillsborough Community College

Incorporating appeals to pathos into persuasive writing increases a writer’s chances of achieving his or her purpose. Read “ Pathos ” to define and understand pathos and methods for appealing to it. The following brief article discusses examples of these appeals in persuasive writing.

An important key to incorporating pathos into your persuasive writing effectively is appealing to your audience’s commonly held emotions. To do this, one must be able to identify common emotions, as well as understand what situations typically evoke such emotions. The blog post “ The 10 Most Common Feelings Worldwide, We Feel Fine ,” offers an interview with Seth Kamvar, co-author of We Feel Fine. According to the post, the 10 most commonly held emotions in 2006-2009 were: better, bad, good, guilty, sorry, sick, well, comfortable, great, and happy (qtd. in Whelan).

Let’s take a look at some potential essay topics, what emotions they might evoke, and what methods can be used to appeal to those emotions.

Example: Animal Cruelty

Related Emotions:

Method Narrative

In “To Kill a Chicken,” Nicholas Kristof describes footage taken by an undercover investigator for Mercy with Animals at a North Carolina poultry slaughterhouse: “some chickens aren’t completely knocked out by the electric current and can be seen struggling frantically. Others avoid the circular saw somehow. A backup worker is supposed to cut the throat of those missed by the saw, but any that get by him are scalded alive, the investigator said” (Kristof).

This narrative account, which creates a cruel picture in readers’ minds, will evoke anger, horror, sadness, and sympathy.

Example: Human Trafficking

- Sadness (sorry)

- Sympathy

Method: Direct Quote

“From Victim to Impassioned Voice” provides the perspective of Asia Graves, a victim of a vicious child prostitution ring who attributes her survival to a group of women: “If I didn’t have those strong women, I’d be nowhere” (McKin).

A quote from a victim of human trafficking humanizes the topic, eliciting sadness and sympathy for the victim(s).

Example: Cyberbullying

Method: empathy for an opposing view.

The concerns of some people who oppose the criminalization of cyberbullying are understandable. For example, Justin W. Patchin, coauthor of Bullying Beyond the Schoolyard: Preventing and Responding to Cyberbullying , opposes making cyberbullying a crime because he views the federal and state governments’ role as one to educate local school districts and provide resources for them (“Cyberbullying”). Patchin does not oppose cyberbullying itself; rather, he takes issue with the government responding to it through criminalization.

Identifying and articulating the opposing view as well as the concerns that underpin it helps the audience experience a full range of sympathy, a commonly held emotion, as a consequence of sincerely investigating and acknowledging another view.

The method a writer uses to persuade emotionally his or her audience will depend on the situation. However, any writer who uses at least one approach will be more persuasive than a writer who ignores opportunities to entreat one of the most powerful aspects of the human experience—emotions.

Works Cited

“Cyberbullying.” Opposing Viewpoints Online Collection . Detroit: Gale, 2015. Opposing Viewpoints in Context . Web. 21 July 2016.

Kristof, Nicholas. “To Kill a Chicken.” The New York Times . The New York Times, 3 May 2015. Web. 20 July 2016.

McKin, Jenifer. “From victim to impassioned voice: Women exploited as a teen fights sexual trafficking of children.” The Boston Globe . Boston Globe Media Partners, 27 Nov. 2012. Web. 20 July 2016.

Whelan, Christine. “The 10 Most Common Feelings Worldwide: We Feel Fine.” The Huffington Post . The Huffington Post, 18 March 2012. Web. 21 July 2016.

Brevity – Say More with Less

Clarity (in Speech and Writing)

Coherence – How to Achieve Coherence in Writing

Flow – How to Create Flow in Writing

Inclusivity – Inclusive Language

The Elements of Style – The DNA of Powerful Writing

Suggested Edits

- Please select the purpose of your message. * - Corrections, Typos, or Edits Technical Support/Problems using the site Advertising with Writing Commons Copyright Issues I am contacting you about something else

- Your full name

- Your email address *

- Page URL needing edits *

- Comments This field is for validation purposes and should be left unchanged.

Featured Articles

Academic Writing – How to Write for the Academic Community

Professional Writing – How to Write for the Professional World

Credibility & Authority – How to Be Credible & Authoritative in Speech & Writing

- school Campus Bookshelves

- menu_book Bookshelves

- perm_media Learning Objects

- login Login

- how_to_reg Request Instructor Account

- hub Instructor Commons

Margin Size

- Download Page (PDF)

- Download Full Book (PDF)

- Periodic Table

- Physics Constants

- Scientific Calculator

- Reference & Cite

- Tools expand_more

- Readability

selected template will load here

This action is not available.

5.2: Logos, Ethos, and Pathos

- Last updated

- Save as PDF

- Page ID 118683

- Tanya Long Bennett

- University of North Georgia via GALILEO Open Learning Materials

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

In order to persuade a particular audience of a particular point, a writer makes decisions about how best to convince the reader. Aristotle recognized three basic appeals that a writer (or orator) should consider when presenting an argument: logos, ethos, and pathos .

Consider this hypothetical plea from Zach to his father: “Dad, could you loan me money for gas until I get my paycheck at the end of the week? If you do, I’ll be able to haul your junk pile to the dump as well as drive myself back and forth to work. I’ll pay you back as soon as I get my check!”

Logos , a Latin term referring to logic, appeals to the reader’s intellect. As readers, we test arguments for their soundness. Does the writer make false assumptions? Are there gaps in the argument? Does the writer leap to conclusions without sufficient evidence to back up his claims? As writers, it is our job to build a solid, well-explained, sufficiently supported argument. In academic texts, logos is usually considered the most important appeal since scholarly research is supposed to be objective and thus more dependent on logic than on emotion (pathos) or on the reputation of the scholar (ethos). What about Zach’s argument above? Essentially, he asserts that a loan from his father would benefit both Zach and his dad. Does the argument seem sound? We do not know why Zach is short on cash this week—his father may be aware that Zach spent most of last week’s check on the newest iPhone, so he does not have enough to cover his gas this week. Thus, there may be factors that undermine Zach’s implication that his request is motivated by responsibility. However, he does offer evidence that the loan will allow him to fulfill his obligations.

Logic is based on either inductive or deductive reasoning. Understanding these types of logic can help us test the soundness of arguments, both our own and those of others.

Inductive Reasoning

You likely use inductive reasoning every day. By this kind of logic, we form conclusions based on samples. Lab experiments, for example, must be repeatable in order for scientists to gather a convincing amount of data to prove a hypothesis. If a scientist hypothesizes that addiction to a particular drug causes a certain, predictable behavior, the experiment must be carefully controlled, and must be repeated hundreds of times in order to prove that the behavior is consistently associated with the addiction and that other possible causes of that behavior have been ruled out. If we observe enough examples of an event occurring under similar circumstances, we can employ inductive reasoning to draw a conclusion about the pattern. For example, if we pay less each time we buy apples at Supermart than when we purchase apples at Pete’s Grocery, we will likely conclude, inductively, that apples are less expensive at Supermart.

Literary argument is often based on inductive reasoning. Here are two illustrations of such reasoning:

- In Robert Frost’s sonnet “Design,” the color white is used ironically to suggest that only a devious designer would clothe the universe’s evil in so much beauty. The “dimpled spider, fat and white”; the “white heal-all” flower that “hold[s] up” the moth for the spider’s feast; and the rhyming of “blight” with “white” and “right” work together to generate the poem’s disturbing sense that the innocence implied in the whiteness of the natural scene is deceptive.

As powerful evidence of the irreversible destruction of war, Hemingway’s The Sun Also Rises presents Jake Barnes’s struggles to overcome the damage incurred during his service as a soldier in World War I. Jake’s difficulty coping with his injury, his tendency to self-medicate with alcohol, his inability to pray, and his failure to sustain an intimate relationship with another person all exemplify the terrible destruction inflicted on him by the war.

When writing a literary analysis essay, such as the paper that might develop from the second argument above, you will need to provide enough examples to support your assertion that the pattern you observed in the text does, indeed, exist.

Deductive Reasoning

Deductive reasoning, on the other hand, is drawing a conclusion based on a logical equation . It can be argued that we see deduction in its purest form in the context of scientific or mathematical reasoning. A logical equation of this sort is based on a proven assumption and/or clearly and inflexibly-defined terms. Commonly manifesting these conditions, computer programs accomplish tasks through deductive logic. For example, Mary, an art major who has completed 24 credit hours, cannot register for English 4500 . This statement is true because the university course enrollment system is governed by the following logic: Only English majors with 30 or more credit hours may register for English 4500. Students who have not officially declared as English majors and/or whose records do not exhibit completion of credit hours equal to or greater than 30 will be automatically prevented from registering for English 4500. Similarly, the following statement is based on deductive logic: Glyptol paint cannot be cleaned up with water only. This conclusion is based on the fact that Glyptol contains alkyds, which are not water soluble. Therefore, clean-up of any paint containing alkyds will require turpentine or another petroleum-based solvent.

Having examined deductive reasoning in its pure form, however, we can see that argument will rarely be required in such a context. Investigation may be required in order to determine the characteristic and/ or definition of a material, but once the facts are ascertained, scientists will not need to debate whether or not alkyds are water-soluble. Persuasion becomes relevant when the issue moves beyond proven facts. As we explore issues of ethics and values, logical reasoning can seem a bit mushy, yet rather than throw up their hands in abandonment of deductive reasoning, humanities scholars generally work hard to establish valid assumptions, or generally agreed-upon notions, that can be used to help humans move closer to reasonable, or logical, social and political beliefs and behaviors.

Sir Arthur Conan Doyle’s famous fictional detective Sherlock Holmes is famous for employing deductive reasoning to solve mysteries. In “Five Orange Pips,” Holmes uses deductive reasoning to work as far as possible toward solving John Openshaw’s case, based on the facts Holmes and Watson have been given:

Now let us consider the situation and see what may be deduced from it. In the first place, we may start with a strong presumption that Colonel Openshaw had some very strong reason for leaving America. Men at his time of life do not change all their habits and exchange willingly the charming climate of Florida for the lonely life of an English provincial town. His extreme love of solitude in England suggests the idea that he was in fear of someone or something, so we may assume as a working hypothesis that it was fear of someone or something which drove him from America. As to what it was he feared, we can only deduce that by considering the formidable letters which were received by himself and his successors. Did you remark the postmarks of those letters?

Equations such as the ones being forwarded by Holmes, when seen in their complete form, comprise a three part logical statement called a syllogism .

The statement includes

- A general statement , or major premise : Middle-aged men do not readily embrace change.

- A minor premise : Colonel Openshaw is a middle-aged man.

- And a conclusion : Colonel Openshaw would not have changed his circumstances without a strong impetus.

Although some might argue that Holmes came to the major premise through inductive reasoning (observing the behavior of many, many middle-aged men), in the above passage, he asserts the major premise as the basis for his deductive logical equation proving that Colonel Openshaw must have had a strong impetus for leaving America. If we agree with Holmes’s premise , we are likely to trust his conclusion .

Here is a more questionable logical equation, considered by the characters of Stephen Crane’s short story “The Open Boat”:

If I am going to be drowned—if I am going to be drowned—if I am going to be drowned, why, in the name of the seven mad gods who rule the sea, was I allowed to come thus far and contemplate sand and trees? Was I brought here merely to have my nose dragged away as I was about to nibble the sacred cheese of life? It is preposterous. If this old ninny-woman, Fate, cannot do better than this, she should be deprived of the management of men’s fortunes. She is an old hen who knows not her intention. If she has decided to drown me, why did she not do it in the beginning and save me all this trouble. The whole affair is absurd.... But, no, she cannot mean to drown me. She dare not drown me. She cannot drown me. Not after all this work.

The following syllogism reflects the men’s attitude:

- Major premise: The world is just and reasonable.

- Minor premise: All of the men in the life-boat are good men and are working hard to survive.

- Conclusion: All of the men should survive.

You can see in the latter example that some times syllogisms are flawed, or illogical. Most of us doubt, at least some of the time, that the universe is indeed just and reasonable, at least by human standards. If it is not just, then the men’s conclusion that they ought to survive may be incorrect.

The occurrence of flawed logic is most problematic when we find an equation in its incomplete form: an enthymeme . If we consider the major premise as the underlying assumption, and recognize that this premise often goes unstated, we see that the enthymeme is a type of elliptical statement that sometimes “leaps” to its conclusion unreasonably. Consider the following examples:

Example \(\PageIndex{1}\)

- Enthymeme: Sarah, don’t eat that beef; it came from Bob’s Café.

- Major premise: All food from Bob’s Café is bad.

- Minor premise: That beef came from Bob’s Café.

- Conclusion: That beef is bad.

Example \(\PageIndex{2}\)

- Enthymeme: Lisa Harmon would be a good hire for our company; she has a degree from Harvard University.

- Major premise: Anyone with a degree from Harvard University would be a good employee for our company.

- Minor premise: Lisa has a degree from Harvard University.

- Conclusion: Lisa would be a good employee for our company.

Example \(\PageIndex{3}\)

- Enthymeme: Kill Bill is a chick flick.

- Major premise: Any movie that features a female protagonist is a chick flick.

- Minor premise: Kill Bill features a female protagonist.

- Conclusion: Kill Bill is a chick flick.

As you test the major premises above, how do they fare? Are they true? If a writer asserted the above enthymemes, would you, as the reader, agree with the major premise of each? Why or why not? What is the danger of reading (or hearing) only the enthymeme and not testing the underlying (unspoken) assumption which would complete the syllogism?

Logical Fallacies

Whether an assertion is based on inductive or deductive reasoning, when we test a claim, it helps to know about the following logical fallacies commonly found in weak arguments:

Bandwagon Argument

This claim encourages us to agree with a particular opinion because “everyone else agrees with it.” Frost’s “Design” implies an evil creator; several important critics agree that this is Frost’s message . Does the text itself support this theory?

Single Cause

This kind of argument suggests that a problem results from one particular cause when the causes may actually be complex and multiple: In The Great Gatsby, it is Gatsby’s decision to pursue a decadent woman like Daisy that leads to his downfall. Are there any other factors that might lay the groundwork for the tragic events of the novel?

This type of statement implies that there are only two options: Roethke’s poem “My Papa’s Waltz” either points to abuse, or it emphasizes the love between father and son. Is it possible for both to be true?

Slippery Slope

In this kind of argument, the writer warns that one step in the “wrong” direction will result in complete destruction: If the instructor curves the grade for this assignment, students will expect a curve on all assignments, and they will lose their motivation to work hard toward their own learning. Is the compromised course grade inevitable as the result of one curved assignment grade? A similar argument is the following: If the government gives welfare to poor citizens, those citizens will become permanently dependent on “handouts” and will lose their motivation to work for a living.

In this approach, the writer holds up an extreme and usually easyto-defeat example of the opposition as the general representative of that opposition instead of considering the opposition’s most reasonable arguments. Senator Jill Campbell was convicted of bribery, confirming that politicians can’t be trusted . Are there any ethical politicians? If so, this conclusion is logically flawed.

False Cause

Here, the writer offers a cause that seems linked to the problem but does not actually establish the causal relationship. T he university cut three class days due to snow, and now I’m failing history; therefore, the university should have added three extra days to the semester.

As you listen to and read arguments forwarded by others, test the claims carefully to ensure that you are not accepting an illogical line of thinking. Also, carefully review your own arguments to avoid forwarding faulty logic yourself!

Ethos, an appeal based on the credibility of the author, can affect a reader’s willingness to trust the writer. This credibility is often generated by the author’s apparent ethics. If the reader perceives that she shares important values with the writer, the door of communication opens wider than if the writer and reader seem to lack common values. Reflecting back to Zach’s request for a loan from his father, Zach does remind his father subtly that the loan will allow him to work, both at his job and at home. This respect for work is likely a value held by Zach’s father, so it becomes important common ground for the argument.

Consider again the previously presented thesis about Hemingway’s The Sun Also Rises :

Hopefully, the writer, let’s call him Bill, will go on to support, with evidence from the text, the claim that the portrayal of Jake’s struggles promotes anti-war sentiment. Beyond the logical soundness of the argument, however, the reader will inevitably react on a personal level to the values underlying the statement. Bill, in his decision to focus on this aspect of the text, seems to appreciate the anti-war stance he observes in the novel. If the reader is sympathetic to this position, she may be more open to Bill’s argument as a whole.

Aside from the writer’s ethics, ethos can also be generated by the author’s credibility, which is usually based on (1) the ability to forward a logical argument (hence, ethos can be affected by logos!), (2) thoroughness of significant research, and (3) credentials proving the writer’s expertise. If Bill is not an expert in the field of literary studies yet, but is a sophomore English Major, he may have no recognizable credentials to persuade the reader in his favor. But if he has been careful and thorough in his presentation of evidence (passages and examples from the text itself) and has considered (and possibly integrated) material from scholarly articles and books to help define and support his argument, his ethos is likely to be strong.

What about pathos , or the appeal to the reader’s emotions? Certainly, Zach’s father will be affected by his feelings for his son Zach as he considers whether to loan Zach the money for gas, but what about in a more academic or professional context? Even though the goal of an academic writer is to approach a research topic as objectively as possible, even scholars are people, and people are emotional creatures. Bill’s awareness of this fact leads him to choose some particularly poignant passages from Hemingway’s novel to support his point:

The damage caused by Jake’s war experience is not only physical but also psychological. For example, after looking in the mirror at the scar from his wound, he lies in bed unable to sleep:

I lay awake thinking and my mind jumping around. Then I couldn’t keep away from it, and I started to think about Brett and all the rest of it went away. I was thinking about Brett and my mind stopped jumping around and started to go in sort of smooth waves. Then all of a sudden I started to cry. Then after a while it was better and I lay in bed and listened to the heavy trams go by and way down the street, and then I went to sleep. (Hemingway 31)

Although Jake makes a convincing show in public of dealing with his trauma, this passage reveals the challenge he faces in trying to cope.

Although Bill’s readers will critically consider whether this passage logically supports Bill’s claim, it is likely that they will also react emotionally to Jake’s anguish, thus reinforcing the persuasive effectiveness of Bill’s argument.

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Perspect Med Educ

- v.7(3); 2018 Jun

Using rhetorical appeals to credibility, logic, and emotions to increase your persuasiveness

Lara varpio.

Department of Medicine, Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences, Bethesda, MD USA

In the Writer’s Craft section we offer simple tips to improve your writing in one of three areas: Energy, Clarity and Persuasiveness. Each entry focuses on a key writing feature or strategy, illustrates how it commonly goes wrong, teaches the grammatical underpinnings necessary to understand it and offers suggestions to wield it effectively. We encourage readers to share comments on or suggestions for this section on Twitter, using the hashtag: #how’syourwriting?

Scientific research is, for many, the epitome of objectivity and rationality. But, as Burke reminds us, conveying the meaning of our research to others involves persuasion. In other words, when I write a research manuscript, I must construct an argument to persuade the reader to accept my rationality .

While asserting that scientific findings must be persuasively conveyed may seem contradictory, it is simply a consequence of how we conduct research. Scientific research is a social activity centred on answering challenging questions. When these questions are answered, the solutions we propose are just that—propositions. Our solutions are accepted by the community until another, better proposition offers a more compelling explanation. In other words, everything we know is accepted for now but not forever .

This means that when we write up our research findings, we need to be persuasive. We must convince readers to accept our findings and the conclusions we draw from them. That acceptance may require dethroning widely held perspectives. It may require having the reader adopt new ways of thinking about a phenomenon. It may require convincing the audience that other, highly respected researchers are wrong. Regardless of the argument I want the reader to accept, I have to persuade the reader to agree with me .

Therefore, being a successful researcher requires developing the skills of persuasion—the skills of a rhetorician. Fortunately for the readers of Perspectives on Medical Education, The Writer’s Craft series offers a treasure trove of rhetorical tools that health professions education researchers can mine.

A primary lesson of rhetoric was developed by Aristotle. He studied rhetoric analytically, investigating all the means of persuasion available in a given situation. He identified three appeals at play in all acts of persuasion: ethos, logos and pathos. The first is focused on the author, the second on the argument, the third on the reader. Together, they support effective persuasion, and so can be harnessed by researchers to powerfully convey the meaning of their research.

Ethos is the appeal focused on the writer. It refers to the character of the writer, including her credibility and trustworthiness. The reader must be convinced that the author is an authority and merits attention. In scientific research, the author must establish her credibility as a rigorous and expert researcher. Much of an author’s ethos, then, lies in using well-reasoned and justified research methodologies and methods. But, a writer’s credibility can be bolstered using a number of rhetorical techniques including similitude and deference .

Similitude appeals to similarities between the author and the reader to create a sense of mutual identification. Using pronouns like we and us, the writer reinforces commonality with the reader and so encourages a sense of cohesion and community. To illustrate, consider the following:

While burnout continues to plague our residents , medical educators have yet to identify the root causes of this problem. We owe it to our residents to delve into this area of inquiry to secure their wellbeing over their lifetime of clinical service.

While burnout continues to plague residents , medical educators have yet to identify the root causes of this problem. Medical educators owe it to their residents to delve into this area of inquiry to secure their wellbeing over their lifetime of clinical service.

In the first sentence, the author aligns herself with the community of medical educators involved in residency education. The writer is part of the we who has to support residents. She makes the burnout problem something she and the reader are both called upon to address. In the second sentence, the author separates herself from this community of educators. She creates social distance between herself and the reader, and thus places the burden of resolving the problem more squarely on the shoulders of the reader than herself.

Both phrasings are equally correct, grammatically. One creates social connection, the other social distance.

Deference is a way for the author to signal respect for others, and personal humility. The writer can demonstrate deference by using phrases such as in my opinion , or through the use of adjectives (e.g., Smith rigorously studied) or adverbs (e.g., the important work by Jones). For example:

The thoughtful research conducted by Jane Doe et al. suggests that resident burnout is more prevalent among those learners who were shamed by attending physicians. Echoing the calls of others [ 1 ], we contend that this work should be extended to also consider the role of fellow learners as potential contributors to resident experiences of burnout.

In this sentence, the author does not present Jane Doe and colleagues as weak researchers, nor as developing findings that should be rejected. Instead, it shows deference to these researchers by acknowledging the quality of their research and a willingness to build on the foundation provided by their findings. (Note how the author also builds ethos via similitude with other scholars by calling the reader’s attention to the fact that other researchers have also called for more research on the author’s suggested extension of Doe’s work).

Readers pick up on the respect authors pay to other researchers. Being rude or unkind in our writing rarely achieves anything except reflecting poorly on the writer.

In sum, as my grandmother used to say: ‘You’ll slide farther on honey than gravel.’ Establishing similitude and showing deference helps to establish your ethos as an author. They help the writer make honey, not gravel.

Logos is the rhetorical appeal that focuses on the argument being presented by the author. It is an appeal to rationality, referring to the clarity and logical integrity of the argument. Logos is, therefore, primarily rooted in the reasoning that holds different elements of the manuscript’s argument together. Do the findings logically connect to support the conclusion being drawn? Are there errors in the author’s reasoning (i.e., logical fallacies) that undermine the logic presented in the manuscript? Logical fallacies will undercut the persuasive power of a manuscript. Authors are well advised to spend time mapping out the premises of their arguments and how they logically lead to the conclusions being drawn, avoiding common errors in reasoning (see Purdue’s on-line writing lab [ 2 ] for 12 of the most common logical fallacies that plague authors, complete with definitions and examples).

However, logos is not merely contained in the logic of the argument itself. Logos is only achieved if the reader is able to follow the author’s logic. To support the reader’s ability to process the logical argument presented in the manuscript, authors can use signposting. Signposting is often accomplished via words (e.g., first, next, specifically, alternatively, also, consequently, etc.) and phrases (e.g., as a result, and yet, for example, in conclusion, etc.) that help the reader to follow the line of reasoning as it moves through the manuscript. Signposts indicate to the reader the structure of the argument to come, where they are in the argument at the moment, and/or what they can expect to come next. Consider the following sentence from one of my own manuscripts. This is the last sentence in the Introduction [ 3 ]:

This study addresses these gaps by investigating the following questions: How often are residents taught informally by physicians and nurses in clinical settings? What competencies are informally taught to residents by physicians and nurses? What teaching techniques are used by physicians and nurses to deliver informal education?

At the end of the Introduction, this sentence offers a map to the reader of how the paper’s argument will develop. The reader can now expect that the manuscript will address each of these questions, in this order. I could also use large-scale signposting, such as sub-headings in the Results, to organize the reading of data related to each of these questions. In the Discussion, I can use small-scale signpost terms and phrases (i.e., however, in contrast, in addition, finally, etc.) to help the reader follow the progression of the argument I am presenting .

I must offer one word of caution here: be sure to use your signposts precisely. If not, your writing will not be logically developed and you will weaken the logos at work in the manuscript. For instance, however signposts a contrasting or contradicting idea:

I enjoy working with residents; however , I loathe completing in-training evaluation reports.

If the writer uses the wrong signpost, the meaning of the sentence falls apart, and so does the logos:

I enjoy working with residents; alternatively , I loathe completing in-training evaluation reports.

Alternatively indicates a different option or possibility. This sentence does not present two different alternatives; it presents two contrasting ideas. Using alternatively confuses the meaning of the sentence, and thus impairs logos.

With clear and precise signposting, the reader will easily follow your argument across the manuscript. This supports the logos you develop as you guide the reader to your conclusions.

Pathos is the rhetorical appeal that focuses on the reader. Pathos refers to the emotions that are stirred in the reader while reading the manuscript. The author should seek to trigger specific emotional reactions in their writing. And, yes, there is room for emotions in scientific research articles. Some of my favourite manuscripts in The Writer’s Craft series are those that help authors elicit specific emotions from the reader.

For instance, in Joining the conversation: the problem/gap/hook heuristic Lingard highlights the importance of ‘hooking’ your audience. The hook ‘convinces readers that this gap [in the current literature] is of consequence’ [ 4 ]. The author must persuade the reader that the argument is important and worthy of the reader’s attention. This is an appeal to the readers’ emotions.

Another example is found in Bonfire red titles. As Lingard explains, the title of your manuscript is ‘advertising for what is inside your research paper’ [ 5 ]. The title must attract the readers’ attention and create a desire within them to read your manuscript. Here, again, is pathos in action in a scientific research paper: grab the reader’s attention from the very first word of the title.

Beyond those already addressed in The Writer’s Craft series, another rhetorical technique that appeals to the emotions of the reader is the strategic use of God-terms [ 1 ] . Burke defined God-terms as words or phrases that are ‘the ultimates of motivation,’ embodying characteristics that are fundamentally valued by humans. To use an analogy from card games (e.g., bridge or euchre), God-terms are like emotional trump cards. God-terms like freedom, justice, and duty call on shared human values, trumping contradictory feelings. By alluding to God-terms in our research, we increase the emotional appeal of our writing. Let us reconsider the example from above:

While burnout continues to plague our residents, medical educators have yet to identify the root causes of this problem. We owe it to our residents to delve into this area of inquiry to secure their wellbeing over their lifetime of clinical service .

Here, the author reminds the reader that residents will be in service as physicians for their lifetime, and that we have a duty (i.e., we owe it ) to support them in that calling to meet the public’s healthcare needs. Invoking the God-terms of service and duty, the writer taps into the reader’s sense of responsibility to support these learners.

It is important not to overplay pathos in a scientific research paper—i.e., readers are keenly intelligent scholars who will easily identify emotional exaggeration. Consider this variation on the previous example:

While burnout continues to ruin the lives of our residents, medical educators have neglected to identify the root causes of this problem. We have a moral obligation to our residents to delve into this area of inquiry to secure their wellbeing over their lifetime of clinical service.

This rephrasing is likely to create a sense of unease in the reader because of the emotional exaggerations it uses. By over-amplifying the appeals to emotion, this rephrasing elicits feelings of refusal and rejection in the reader. Instead of drawing the reader in, it pushes the reader away. When it comes to pathos, a light hand is best.

Peter Gould famously stated: ‘data can never speak for themselves’ [ 6 ]. Researchers must explain them. In that explaining, we endeavour to convince the audience that our propositions should be accepted. While the science in our research is at the core of that persuasion, there are techniques from rhetoric that can help us convince readers to accept our arguments. Ethos, logos and pathos are appeals that, when used intentionally and judiciously, can buoy the persuasive power of your manuscripts.

The views expressed herein are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the United States of America’s Department of Defense or other federal agencies.

PhD, is a professor in the Department of Medicine at Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences, MD. Her program of research investigates the many kinds of teams involved in health professions education (e.g., interprofessional clinical care teams, health professions education scholarship unit teams, etc.). A self-professed ‘theory junky’, she uses theories from the social sciences and humanities, and qualitative methods/methodologies to build practical, theory-based knowledge.

Wherever there is meaning there is persuasion. —Kenneth Burke [ 1 ]

Choose Your Test

Sat / act prep online guides and tips, ethos, pathos, logos, kairos: the modes of persuasion and how to use them.

General Education

Ethos, pathos, logos, and kairos all stem from rhetoric—that is, speaking and writing effectively. You might find the concepts in courses on rhetoric, psychology, English, or in just about any other field!

The concepts of ethos, pathos, logos, and kairos are also called the modes of persuasion, ethical strategies, or rhetorical appeals. They have a lot of different applications ranging from everyday interactions with others to big political speeches to effective advertising.

Read on to learn about what the modes of persuasion are, how they’re used, and how to identify them!

What Are the Modes of Persuasion?

As you might have guessed from the sound of the words, ethos, pathos, logos, and kairos go all the way back to ancient Greece. The concepts were introduced in Aristotle’s Rhetoric , a treatise on persuasion that approached rhetoric as an art, in the fourth century BCE.

Rhetoric was primarily concerned with ethos, pathos, and logos, but kairos, or the idea of using your words at the right time, was also an important feature of Aristotle’s teachings.

However, kairos was particularly interesting to the Sophists, a group of intellectuals who made their living teaching a variety of subjects. The Sophists stressed the importance of structuring rhetoric around the ideal time and place.

Together, all four concepts have become the modes of persuasion, though we typically focus on ethos, pathos, and logos.

What Is Ethos?

Though you may not have heard the term before, ‘ethos’ is a common concept. You can think of it as an appeal to authority or character—persuasive techniques using ethos will attempt to persuade you based on the speaker’s social standing or knowledge. The word ethos even comes from the Greek word for character.

An ethos-based argument will include a statement that makes use of the speaker or writer’s position and knowledge. For example, hearing the phrase, “As a doctor, I believe,” before an argument about physical health is more likely to sway you than hearing, “As a second-grade teacher, I believe.”

Likewise, celebrity endorsements can be incredibly effective in persuading people to do things . Many viewers aspire to be like their favorite celebrities, so when they appear in advertisements, they're more likely to buy whatever they're selling to be more like them. The same is true of social media influencers, whose partnerships with brands can have huge financial benefits for marketers .

In addition to authority figures and celebrities, according to Aristotle, we’re more likely to trust people who we perceive as having good sense, good morals, and goodwill —in other words, we trust people who are rational, fair, and kind. You don’t have to be famous to use ethos effectively; you just need whoever you’re persuading to perceive you as rational, moral, and kind.

What Is Pathos?

Pathos, which comes from the Greek word for suffering or experience, is rhetoric that appeals to emotion. The emotion appealed to can be a positive or negative one, but whatever it is, it should make people feel strongly as a means of getting them to agree or disagree.

For example, imagine someone asks you to donate to a cause, such as saving rainforests. If they just ask you to donate, you may or may not want to, depending on your previous views. But if they take the time to tell you a story about how many animals go extinct because of deforestation, or even about how their fundraising efforts have improved conditions in the rainforests, you may be more likely to donate because you’re emotionally involved.

But pathos isn’t just about creating emotion; it can also be about counteracting it. For example, imagine a teacher speaking to a group of angry children. The children are annoyed that they have to do schoolwork when they’d rather be outside. The teacher could admonish them for misbehaving, or, with rhetoric, he could change their minds.

Suppose that, instead of punishing them, the teacher instead tries to inspire calmness in them by putting on some soothing music and speaking in a more hushed voice. He could also try reminding them that if they get to work, the time will pass quicker and they’ll be able to go outside to play.

Aristotle outlines emotional dichotomies in Rhetoric . If an audience is experiencing one emotion and it’s necessary to your argument that they feel another, you can counterbalance the unwanted emotion with the desired one . The dichotomies, expanded upon after Aristotle, are :

- Anger/Calmness

- Friendship/Enmity

- Fear/Confidence

- Shame/Shamelessness

- Kindness/Unkindness

- Pity/Indignation

- Envy/Emulation

Note that these can work in either direction; it’s not just about swaying an audience from a negative emotion to a positive one.