Log in or sign up for Rotten Tomatoes

Trouble logging in?

By continuing, you agree to the Privacy Policy and the Terms and Policies , and to receive email from the Fandango Media Brands .

By creating an account, you agree to the Privacy Policy and the Terms and Policies , and to receive email from Rotten Tomatoes and to receive email from the Fandango Media Brands .

By creating an account, you agree to the Privacy Policy and the Terms and Policies , and to receive email from Rotten Tomatoes.

Email not verified

Let's keep in touch.

Sign up for the Rotten Tomatoes newsletter to get weekly updates on:

- Upcoming Movies and TV shows

- Trivia & Rotten Tomatoes Podcast

- Media News + More

By clicking "Sign Me Up," you are agreeing to receive occasional emails and communications from Fandango Media (Fandango, Vudu, and Rotten Tomatoes) and consenting to Fandango's Privacy Policy and Terms and Policies . Please allow 10 business days for your account to reflect your preferences.

OK, got it!

Movies / TV

No results found.

- What's the Tomatometer®?

- Login/signup

Movies in theaters

- Opening this week

- Top box office

- Coming soon to theaters

- Certified fresh movies

Movies at home

- Fandango at Home

- Netflix streaming

- Prime Video

- Most popular streaming movies

- What to Watch New

Certified fresh picks

- Furiosa: A Mad Max Saga Link to Furiosa: A Mad Max Saga

- Kingdom of the Planet of the Apes Link to Kingdom of the Planet of the Apes

- Babes Link to Babes

New TV Tonight

- Evil: Season 4

- Trying: Season 4

- Tires: Season 1

- Fairly OddParents: A New Wish: Season 1

- Stax: Soulsville, U.S.A.: Season 1

- Lolla: The Story of Lollapalooza: Season 1

- Jurassic World: Chaos Theory: Season 1

- Mulligan: Season 2

- The 1% Club: Season 1

Most Popular TV on RT

- Outer Range: Season 2

- Bodkin: Season 1

- The Lord of the Rings: The Rings of Power: Season 2

- Bridgerton: Season 3

- Fallout: Season 1

- Dark Matter: Season 1

- The Sympathizer: Season 1

- Baby Reindeer: Season 1

- The 8 Show: Season 1

- Best TV Shows

- Most Popular TV

- TV & Streaming News

Certified fresh pick

- Bridgerton: Season 3 Link to Bridgerton: Season 3

- All-Time Lists

- Binge Guide

- Comics on TV

- Five Favorite Films

- Video Interviews

- Weekend Box Office

- Weekly Ketchup

- What to Watch

Mad Max Movies Ranked by Tomatometer

Mad Max In Order: How to Watch the Movies Chronologically

Asian-American Native Hawaiian Pacific Islander Heritage

What to Watch: In Theaters and On Streaming

Weekend Box Office Results: John Krasinski’s IF Rises to the Top

Hugh Jackman Knew “Deep in His Gut” That He Wanted to Play Wolverine Again

- Trending on RT

- Furiosa First Reviews

- Most Anticipated 2025 Movies

- Cannes Film Festival Preview

- TV Premiere Dates

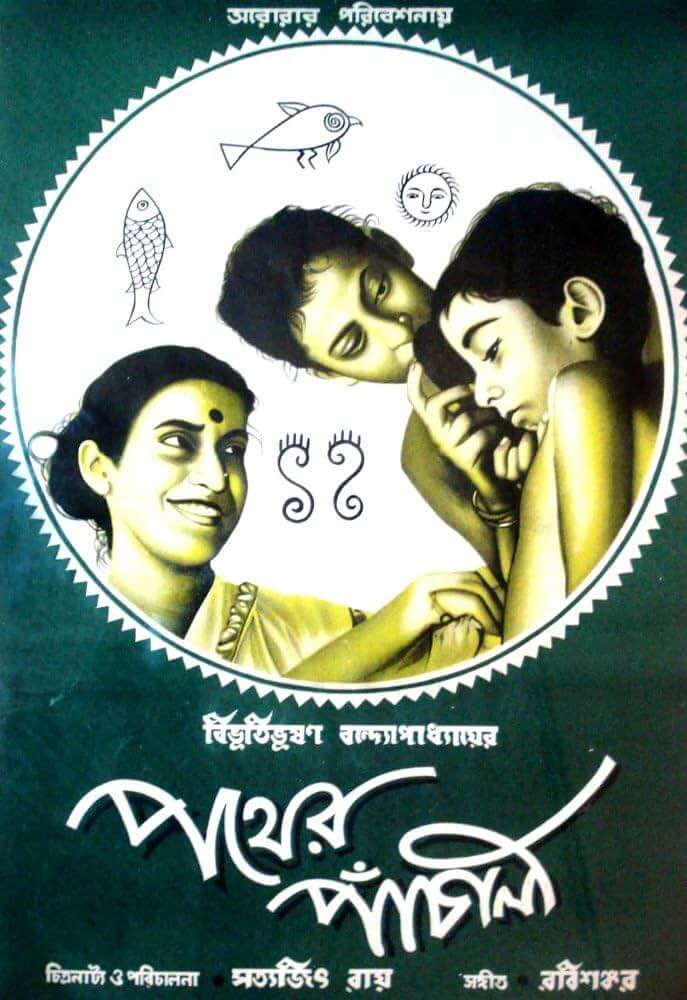

Pather Panchali

Where to watch.

Watch Pather Panchali with a subscription on Max, rent on Fandango at Home, Prime Video, or buy on Fandango at Home, Prime Video.

What to Know

A film that requires and rewards patience in equal measure, Pather Panchali finds director Satyajit Ray delivering a classic with his debut.

Critics Reviews

Audience reviews, cast & crew.

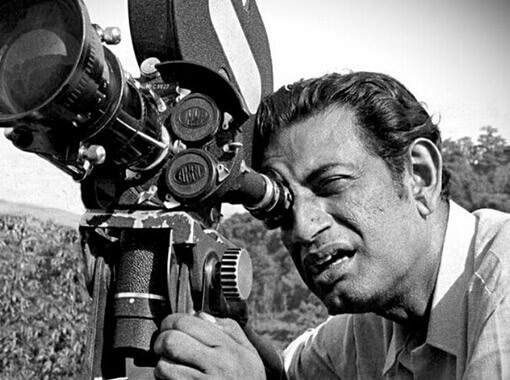

Satyajit Ray

Kanu Bannerjee

Harihar Ray

Karuna Bannerjee

Sarbojaya Ray

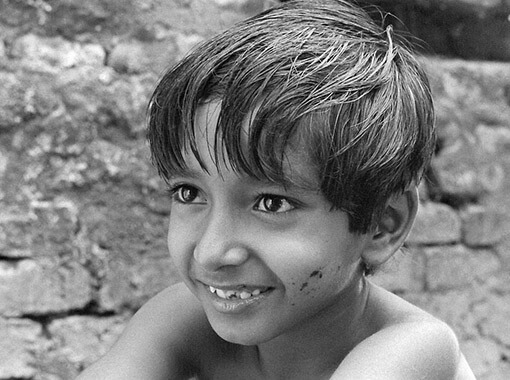

Subir Bannerjee

Uma Das Gupta

Chunibala Devi

Indir Thakrun

More Like This

Related movie news.

Movie Reviews

Tv/streaming, collections, great movies, chaz's journal, contributors, the apu trilogy.

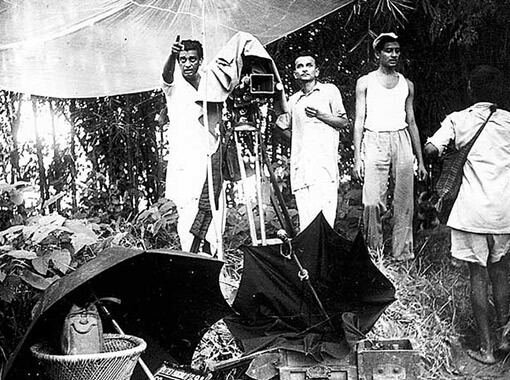

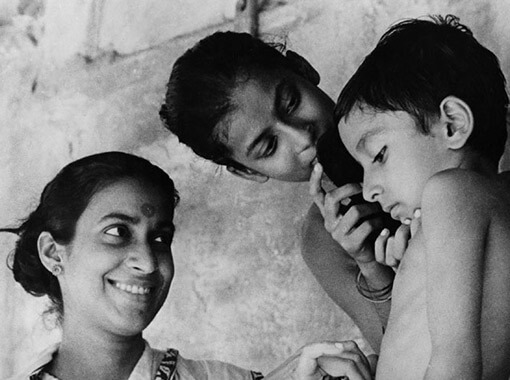

Ray (1921-1992) was a commercial artist in Calcutta with little money and no connections when he determined to adapt a famous serial novel about the birth and young manhood of Apu--born in a rural village, formed in the holy city of Benares, educated in Calcutta, then a wanderer. The legend of the first film is inspiring; how on the first day Ray had never directed a scene, his cameraman had never photographed one, his child actors had not even been tested for their roles--and how that early footage was so impressive it won the meager financing for the rest of the film. Even the music was by a novice, Ravi Shankar , later to be famous.

The trilogy begins with "Pather Panchali," filmed between 1950 and 1954. Here begins the story of Apu when he is a boy, living with his parents, older sister and ancient aunt in the ancestral village to which his father, a priest, has returned despite the misgivings of the practical mother. The second film, "Aparajito" (1956), follows the family to Benares, where the father makes a living from pilgrims who have come to bathe in the holy Ganges. The third film, "The World of Apu" (1959), finds Apu and his mother living with an uncle in the country; the boy does so well in school he wins a scholarship to Calcutta. He is married under extraordinary circumstances, is happy with his young bride, then crushed by the deaths of his mother and his wife. After a period of bitter drifting, he returns at last to take up the responsibility of his son.

This summary scarcely reflects the beauty and mystery of the films, which do not follow the punched-up methods of conventional biography but are told in the spirit of the English title of the first film, "The Song of the Road." The actors who play Apu at various ages from about 6 to 29 have in common a moody, dreamy quality; Apu is not sharp, hard or cynical, but a sincere, naive idealist, motivated more by vague yearnings than concrete plans. He reflects a society that does not place ambition above all, but is philosophical, accepting, optimistic.

He is his father's child, and in the first two films we see how his father is eternally hopeful that something will turn up--that new plans and ideas will bear fruit. It is the mother who frets about money owed the relatives, about food for the children, about the future. In her eyes, throughout all three films, we see realism and loneliness, as her husband and then her son cheerfully go away to the big city and leave her waiting and wondering.

The most extraordinary passage in the three films comes in the third, when Apu, now a college student, goes with his best friend, Pulu, to attend the wedding of Pulu's cousin. The day has been picked because it is astrologically perfect--but the groom, when he arrives, turns out to be stark mad. The bride's mother sends him away, but then there is an emergency, because Aparna, the bride, will be forever cursed if she does not marry on this day, and so Pulu, in desperation, turns to Apu--and Apu, having left Calcutta to attend a marriage, returns to the city as the husband of the bride.

Sharmila Tagore, who plays Aparna, was only 14 when she made the film. She projects exquisite shyness and tenderness, and we consider how odd it is to be suddenly married to a stranger. "Can you accept a life of poverty?" asks Apu, who lives in a single room and augments his scholarship with a few rupees earned in a print shop. "Yes," she says simply, not meeting his gaze. She cries when she first arrives in Calcutta, but soon sweetness and love shine out through her eyes. Soumitra Chatterjee, who plays Apu, shares her innocent delight, and when she dies in childbirth it is the end of his innocence and, for a long time, of his hope.

The three films were photographed by Subrata Mitra , a still photographer who Ray was convinced could do the job. Starting from scratch, at first with a borrowed 16mm camera, Mitra achieves effects of extraordinary beauty: Forest paths, river vistas, the gathering clouds of the monsoon, water bugs skimming lightly over the surface of a pond. There is a fearsome scene as the mother watches over her feverish daughter while the rain and winds buffet the house, and we feel her fear and urgency as the camera dollies again and again across the small, threatened space. And a moment after a death, when the film cuts shockingly to the sudden flight of birds.

I heard a distant echo of the earliest days of the filming, perhaps, when Subrata Mitra was honored at the Hawaii Film Festival in the early 1990s, and in accepting a career award he thanked, not Satyajit Ray, but--his camera, and his film. On those first days of shooting it must have been just that simple, the hope of these beginners that their work would bear fruit.

What we sense all through "The Apu Trilogy" is a different kind of life than we are used to. The film is set in Bengal in the 1920s, when in the rural areas life was traditional and hard. Relationships were formed with those who lived close by; there is much drama over the theft of some apples from an orchard. The sight of a train, roaring at the far end of a field, represents the promise of the city and the future, and trains connect or separate the characters throughout the film, even offering at one low point a means of possible suicide.

The actors in the films have all been cast from life, to type; Italian neorealism was in vogue in the early 1950s, and Ray would have heard and agreed with the theory that everyone can play one role--himself. The most extraordinary performer in the films is Chunibala Devi, who plays the old aunt, stooped double, deeply wrinkled. She was 80 when shooting began; she had been an actress decades ago, but when Ray sought her out, she was living in a brothel, and thought he had come looking for a girl. When Apu's mother angers at her and tells her to leave, notice the way she appears at the door of another relative, asking, "Can I stay?" She has no home, no possessions except for her clothes and a bowl, but she never seems desperate because she embodies complete acceptance.

The relationship between Apu and his mother observes truths that must exist in all cultures: how the parent makes sacrifices for years, only to see the child turn aside and move thoughtlessly away into adulthood. The mother has gone to live with a relative, as little better than a servant ("they like my cooking"), and when Apu comes to visit during a school vacation, he sleeps or loses himself in his books, answering her with monosyllables. He seems in a hurry to leave, but has second thoughts at the train station, and returns for one more day. The way the film records his stay, his departure and his return says whatever can be said about lonely parents and heedless children.

I watched "The Apu Trilogy" recently over a period of three nights, and found my thoughts returning to it during the days. It is about a time, place and culture far removed from our own, and yet it connects directly and deeply with our human feelings. It is like a prayer, affirming that this is what the cinema can be, no matter how far in our cynicism we may stray.

Roger Ebert

Roger Ebert was the film critic of the Chicago Sun-Times from 1967 until his death in 2013. In 1975, he won the Pulitzer Prize for distinguished criticism.

Now playing

Simon Abrams

The Long Game

Don't Tell Mom the Babysitter's Dead

Peyton robinson.

Black Twitter: A People's History

Rendy jones.

Kaiya Shunyata

Star Wars -- Episode I: The Phantom Menace

Film credits.

The Apu Trilogy (1959)

Directed by.

- Satyajit Ray

Latest blog posts

Cannes 2024 Video #4: Jason Gorber on Canada's Films

Cannes 2024: Anora, Limonov, Ernest Cole: Lost and Found, Lula

The Legacy of David Bordwell; or, The Memorial Service as Network Narrative

Senua’s Saga: Hellblade 2 Wastes Its Potential

Pather Panchali (1955)

B ecause of funding problems, it took Calcutta-born filmmaker Satyajit Ray three years to complete his debut film, Pather Panchali. It’s one of those movies that exists almost against all odds, and also one of the most beautiful films ever made, in any language. It’s unlikely your childhood was anything like Apu’s, yet his story is a dream of every childhood, a recollection—or a wish—of love and family that reaches deep inside us. Young Apu (Subir Banerjee) lives in the Bengali countryside with his mother and father (Karuna Banerjee and Kanu Banerjee), his older sister, Durga (Shampa “Runki” Banerjee), and an elderly live-in auntie (Chunibala Devi). Apu’s father comes from a long, proud lineage of writers, but he has failed to make a good living for his little family; they once owned a nearby orchard, but they’ve had to sell it off to survive. Apu is often impish and naughty, but his family adores him, building a world of warmth and care for him despite their financial difficulties. Ray, in gorgeously silvery black-and-white cinematography, captures the texture of childhood—in the way, for instance, Apu and Durga rush out into the fields when the train passes by, excited by its speed and noise and promise of some mysterious elsewhere. The beauty of Pather Panchali (adapted from an autobiographical novel by Bengali writer Bibhutibhushan Bandyopadhyay) is matched by its two superb sequels, Aparajito , from 1957, and Apur Sansar , from 1959. These rapturous meditations on the power of memory, and on the nature of love and loss, are for all of us to enjoy. Akira Kurosawa said, “Not to have seen the cinema of Ray means existing in the world without seeing the sun or the moon.” If you won’t take my word for it, take his.

- The New Face of Doctor Who

- How Private Donors Shape Birth-Control Choices

- What Happens if Trump Is Convicted ? Your Questions, Answered

- Putin’s Enemies Are Struggling to Unite

- The Deadly Digital Frontiers at the Border

- Scientists Are Finding Out Just How Toxic Your Stuff Is

- The 31 Most Anticipated Movies of Summer 2024

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Contact us at [email protected] .

The Godfather Part II (1974)

Jaws (1975), e.t. the extra-terrestrial (1982), the empire strikes back (1980), little women (2019).

The Definitives

Critical essays, histories, and appreciations of great films

Pather Panchali

Essay by brian eggert august 14, 2018.

Satyajit Ray made films about how people in India negotiate their surroundings and culture. His boundless humanism defined his work, which began in 1955 with Pather Panchali ( Song of the Little Road ), the first entry in his celebrated Apu Trilogy, followed by Aparajito (1956, The Unvanquished ) and Apu Sansar (1959, The World of Apu ). A Bengali filmmaker who purveyed characters with vast emotional depth, Ray avoided the ideological and political, and he approached human beings as individuals who, regardless of their views, were allowed to speak their minds. Ray, whose films earn comparisons to the work of Jean Renoir for their interest in the complexity of human beings, was described by Renoir as “the father of Indian cinema.” However, Ray’s distinct perspective and poetic style developed in contrast to primary modes of Indian cinema, neither attuned to the popular commercial Hindi industry that dominates much of the country’s cinematic output nor invested in the emergence of activist political filmmaking, as with his social realist contemporaries Mrinal Sen or Ritwik Ghatak. Based on the novel by Bibhutibhushan Banerjee, Pather Panchali , though set in a rural village in the 1930s, has a timeless, natural style that many at the time confused with documentary realism, and when the film debuted, Ray’s style earned comparisons to ethnographic documentary pioneer Robert Flaherty. A closer inspection of the film and its creation, Ray’s divergence from other Indian cinema, and further, his uniqueness among all of cinema’s authorial voices, reveals his debut as an artwork attesting to the director as a lyrical observer of humanity.

Ray’s individualism, and the exceptionality of his films within his country’s national cinema, become apparent when characterizing the Indian film industry (understanding, of course, that any such characterization of an entire industry remains dependent on some generalizations). Indian film had developed in a trajectory similar to that of Hollywood, where, in the early 1920s and 1930s, a few major studios concentrated on cheap production costs and high profits. Early Indian films had neither the advanced facilities nor the inclination to make more sophisticated efforts; instead, unpolished films contained feats of action, stage-like performances, and mythological subject matter in an economical, mostly self-contained industry. An inbuilt audience in the hundreds of millions established a stable marketplace for these Hindi-language films—meaning production, distribution, and exhibition took place within India’s borders. Whereas Hollywood titles dominated the screens of other countries around the world, leaving only a small percentage for the local, undeveloped national film industries, India retained more than 60 percent of their own films on their theater screens. Moreover, after India achieved independence from the British Empire in 1947, the nationalized interests of the Indian National Congress emphasized the need for a strong national cinema in the wake of India’s growing capitalism, and the volume of Indian popular films steadily increased to become the largest film industry in the world.

Ray’s brand of filmmaking emerged as part of the national government’s desire to create an alternative New Indian Cinema, with a drive toward social awareness and a conscious departure from commercial cinema. Many in India believed that the country, with its newly achieved independence from British colonial rule, would be better served by social realism, polished filmmaking, and authentic storytelling, as opposed to the cheap, fanciful, and often outlandish releases that pervaded the Indian film industry. In the 1960s, the Indian government established the Film Finance Corporation and the Indian Motion Picture Export Association—which eventually merged in 1980 to become the National Film Development Corporation—to foster social filmmaking for international distribution on the arthouse circuit. However, many of the films produced from this New Indian Cinema movement were unpopular; their primary market was, ironically, on the international scene, though many went unscreened by Western audiences. Even most Ray films, functioning within the edicts of the New Indian Cinema for the first years of his career, did not arrive in the U.S. until after his death in 1992, just after he became the first Indian filmmaker to receive an honorary Academy Award, launching a significant effort to restore his body of work.

Before becoming the so-called father of Indian cinema, Ray received his education in filmmaking not from formal training but by studying the craft of classic Hollywood and writing extensive, thoughtful film criticism and theory. He was “anxious to study films, not to make them,” he told interviewer Almay Benegal for the documentary Satyajit Ray (1984). Although he continued to see Bengali films from directors such as Bimal Roy and Nitin Bose, he watched Bengali films to learn how not to make films, calling them “false, unrealistic, shoddy, commercial in a bad way.” He determined that Indian films suffered from a lack of technical and actorly polish when compared to Hollywood or European cinema, and he particularly cited John Ford, Ernst Lubitsch, William Wyler, Frank Capra, and David Lean as role models in his understanding of the craft. During this period, Ray also studied documentarian Flaherty, whose aesthetics from Nanook of the North (1922) to the Sabu-starrer Elephant Boy (1937) instilled a pseudo-realist approach, capturing Nature and indigenous people with a conflicting sense of control and veracity. Whenever Ray could get his hands on a print of a Jean Renoir film, he did. Ray also considered Renoir’s The Rules of the Game (1938) one of the finest films ever made, and he admired Renoir’s humanist ideals and open-mindedness toward characters that another filmmaker would have judged harshly.

With this ideal in mind, Ray set out to make Pather Panchali over the course of two years, working on it intermittently as he maintained a career in advertising. The project first came to Ray in 1950, when he was asked to illustrate a children’s version of the hugely popular book Pather Panchali , first published in a serialized Bengali periodical between 1928 and 1929, and then in novel form in 1929. Ray was charmed and engrossed by the text, and he resolved to adapt the material as his first film. By this time, the novel had already become a classic in Bengal and ensured the proposed film an inbuilt audience. Ray wrote his treatment and composed detailed sketches of his proposed film to interest producers and investors before acquiring the rights to the Banerjee’s novel. He eventually met with Banerjee’s widow who approved of the project, knowing of Ray’s talented grandfather and father, both famous artisans. Many censured her decision given Ray’s inexperience as a filmmaker, but she nonetheless remained supportive of the fledgling director throughout the next half-decade, as Ray slowly progressed on his first film. For two years, Ray pitched his film idea to potential investors, but many balked at his notion of shooting in real locations with amateur actors; and they could not imagine an Indian motion picture without song and dance. “They believed only in a certain kind of commercial cinema,” Ray wrote later. “But one kept hoping that presented with something fresh and original and affecting, they would change.” By 1952, Ray had convinced no investors to support his unconventional project. He resolved to borrow money from various friends and his insurance company to shoot footage that, over time, convinced investors to support the entire production.

Ray filmed Pather Panchali in sequence on the Bengali countryside, using untrained actors and subpar equipment. He taught himself the practice and artistry of filmmaking as he went along. This has resulted in many film scholars noting how the production looks to improve in its craft as the story advances. Always scraping by, the production seldom had access to the right lenses early on, and some critics have noted arbitrariness of the lenses and how they’re used in the first half. Intermittent shooting began in 1952, mired by the production’s deficient budget, meager technical facilities, and the lack of experience among the director and his band of friends behind the scenes. They shot in two primary locations: the village of Boral, where the ancestral home of the story’s family and a nearby pond were located; and also, a field some hundred miles away. Ray found actors young and old with stage experience. Most, aside from Subir Banerjee, the boy who plays Apu, had acted before. But as Apu has few lines and often remains a spectator to the film’s drama, he wasn’t required to give an excellent performance, just react as a child would naturally. The director’s most significant find was Chunibala Devi for Auntie, the friendly neighbor of the central family. She was an octogenarian who uncannily met the author’s description of the character, and yet she served Ray’s needs: she looked the distinguished part, had been an actress earlier in the century, and maintained a sharp enough wit to remember lines and give a thorough performance—despite living in Calcutta’s red-light district, where she supported an opium addiction.

While on hiatus, Ray had a chance meeting with Monroe Wheeler, the Director of Publications and Exhibitions at New York’s Museum of Modern Art (MoMA). Wheeler was introduced to Ray during his brief trip to India to explore textiles in Calcutta for exhibition in MoMA. Ray showed Wheeler early stills of Pather Panchali and piqued his interest. Wheeler, in turn, contacted the museum and arranged for a rough cut to be screened by a representative who described Ray’s project as an anticipated “documentary film” that “magnificently projected by the village folk without a whiff of ham”—a mischaracterization suggesting that Ray had made a documentary in the style of Robert Flaherty. Since Flaherty’s brand of documentary attracted audiences, distributors became interested in Pather Panchali well before its completion. Around the same time, funding from a government grant provided the resources Ray needed to complete his production. Dr. B.C. Roy, the Chief Minister of the Government of West Bengal, was shown edited footage of the production through a mutual connection of Ray’s mother in hopes that the government would provide funding. Similar to Wheeler and many officials who inspected the footage, Roy believed the project to be a documentary. Regardless, the government’s interest in supporting a socially conscious national cinema movement, which would eventually develop into the New Indian Cinema that emerged in the 1960s, meant Ray received a grant and could complete his film. The deal to finish his work, however, left the director with no income for his efforts and no rights to the international release.

Even with funding secured, Ray’s production was tested by the monsoon season, which allowed him extra time to reconsider his approach, as his cast and crew waited for the rains to subside. During this time, he thought and rethought his process, planned nearly every shot in detail, and edited the existing footage together. In his subsequent films, he continued the process of meticulous preplanning and editing during production, allowing him insight and control over the end result. Still, the funding meant Ray was now on a deadline. He had agreed to have the film ready by May 1955 for a screening at MoMA, meaning he had to scramble to complete shooting, edit the picture, add music, and loop the actors’ voices where necessary. Wheeler had already sent a representative to Calcutta to check on Ray’s progress: John Huston, who was going to India to scout locations for The Man Who Would Be King (eventually made in 1975), saw a rough cut of scenes from Pather Panchali and noted that, while beautiful, there was perhaps too much meandering on the screen. Whether or not Huston understood the project’s desire to capture rural Bengali life, he nonetheless recognized Ray’s work as that of a great filmmaker. Meanwhile, Ray and his production team lived inside the Bengal Film Laboratories for a week to complete a print in time for his MoMA deadline.

Set in the crumbling, ancestral Bengali village of Nischindipur, the screen story follows one family’s survival through Ray’s observations on life, death, and Nature. The father, the optimistic Harihar (Kanu Banerjee), serves as a traveling Hindu priest and leaves his careworn wife, Sarbajaya (Karuna Banerjee), to care for the family and tend to the household while he is gone. Their spirited and curious daughter Durga (Uma Das Gupta) is soon joined by a new brother. The birth of a second child brings an infant boy named Apu into the family. Together, they live among decaying stones with Indir “Auntie” Thakrun (Chunibala Devi), an elderly woman and neighbor who relies on the family’s care. As years pass and Apu (Subir Banerjee) grows into a young boy, Sarbajaya dreams of a better life, worrying about her husband’s lack of income, having enough rice and clothes, finding a husband for Durga, and her new son. “How will he survive?” she asks. “Was he even born to survive?” Though Harihar assures his wife that he will soon find work and all will be resolved, Sarbajaya laments their immobility. “I had lots of dreams once,” she reflects in a sentiment echoed by the sound of a locomotive in the distance, and the possibility and promise of modernity. Durga dreams of seeing the train someday and, after sneaking away with Apu, spies the machine from a field as it passes through the landscape, its plumes of smoke leaving a trail in the sky, carrying the promise of adventure, an unknown and limitless world that seems impossibly far away.

Everyone in Pather Panchali dreams of something better, but not everyone sees their dreams come to fruition. Though Ray depicts the hardships of the idyllic village, rural lifestyle, and household in poverty, dreaming and endurance define these characters, sometimes in tragic ways. When Durga and Apu return from seeing the train, they find Auntie seated on the ground, unresponsive and dead. An earlier scene where Auntie asks if an elderly woman, too, can’t have dreams for a better life, reverberates through her death, and Durga’s. As if defiantly welcoming the sublimity of Nature in the wake of Auntie’s passing, Durga embraces a torrential monsoon downpour, though her impulsive behavior leads to her taking ill. Apu, having watched Durga play from a distance, seems to learn a valuable, if hard-won lesson. With Harihar away looking for work, Sarbajaya cares for the sickly Durga, who succumbs to her illness during a stormy night. In a tragic irony, Harihar has secured a job in the holy city of Benares. After Durga’s death, the family resolves to leave, and Apu, having been a mostly passive observer for much of the drama, carries its lessons with him into a new beginning.

The first screening of Ray’s completed film took place in New York, oddly enough, as the director had scrambled so fast to piece together what was called The Story of Apu and Durga to meet his MoMA deadline, he did not have time to view his work in its entirety. The screening went well, and Wheeler sent his congratulations, whereas in India the West Bengal Government handed over distribution to Aurora Films, which set a release date of August 26, 1955. Without a marketing budget, Ray himself designed posters and distributed them in Calcutta to spread the word. The film’s box-office was slow at first. Pather Panchali opened in a single theater in Calcutta, and it took weeks for word to spread of its impact. Indian critics, among them Bengali filmmaker Ritwik Ghatak, appreciated the film’s “sense of beauty, its bursts, of visual ecstasy and of mental passion” rather than the strain of ethnographic realism that attracted Western viewers. Within a few weeks, Ray’s first film had earned a modest box office and transitioned out of Indian theaters, and Pather Panchali would soon arrive on the international festival circuit. As the book concentrated on village life and met with the ideals of New Indian Cinema, Pather Panchali would be, according to Ray scholar Chandak Sengoopta, “a serious programme for the reform of Indian cinema that was shaped implicitly by the nationalistic optimism of the period.” In addition to being the first major work of Indian realism, Pather Panchali also became the first Indian film screened for Western audiences. Other social realist filmmakers, such as Nimai Ghosh and K.A. Abbas, sought to make important movies for the new India, although their efforts were not as impactful as Pather Panchali on an international scale.

Given the lack of Indian cinema to appear stateside, U.S. distributors avoided booking the film in any great numbers, despite its win of the Special Jury Prize at the 1956 Cannes Film Festival. Western critics, meanwhile, failed to recognize the film’s artistic significance, even while praising its naturalism and Ray’s sensitivity to the subject matter. In the U.S., reviewers and distributors alike continued to characterize Pather Panchali as a documentary of sorts, ignoring the film’s literary origins, acting, music, or photography. An article in New York magazine called the film “a worthy descendant of the tribe” associated with Flaherty’s depictions of other cultures. They overlooked its fictional origins and failed to recognize that, unlike Italian Neorealism, there was not necessarily a need for a grand statement in Pather Panchali ; rather, the film’s warmth exists in the viewer’s capacity for empathy and appreciation of the beauty onscreen. “In our sophistication we had learned to react to stories and situations, themes and symbols in our films,” wrote critic John Flaus years later. “We had lost the habit of reacting to people. We were unprepared in our art for compassion, unspoiled and unqualified.”

Ray’s associations with Flaherty, then, stem from Western viewers looking at his work through preconceived notions about non-Anglo cultures, seeing them as “primitive” or “exotic,” and having a certain ethnographic sameness. Viewers at the time also maintained a lack of knowledge about the source material or Indian film industry, assuming that an Indian filmmaker could not produce a work that created a sense of realism, while at the same time being entirely fictional. Then again, people were convinced of Nanook of the North ’s realism too, and Flaherty’s tactics were later shown to be manipulative. Nanook of the North seemed to document the life of an Inuit hunter in the Canadian wilderness, but Flaherty was eventually revealed to have guided the dramaturgy more than he initially admitted. After all, a cursory examination of Ray’s camera angles, use of editing and montage, and the polished quality to his scenes reveals a distinctly mannerist approach not traditionally associated with a docu-style. However, as documentaries were comparatively uncommon in 1950 compared to their omnipresence today, it’s easy to understand why critics and the Flaherty Foundation mischaracterized Pather Panchali as a documentary subject.

Nevertheless, Ray made clear aesthetic choices about how to shoot Pather Panchali , and a conscious decision to adopt De Sica-esque realism and the humanist observation of Renoir, both through a defined aesthetic. Ray once said of a director’s approach to realism, “There is no ready-made reality which he can straightaway capture on film. What surrounds him is only raw material. Objects, locales, people, speech, viewpoints—everything must be carefully chosen, to serve the ends of his story. In other words, creating reality is part of the creative process, where the imagination is aided by the eye and the ear.” In aide of creating this reality, Ray despised improvisations and only occasionally used them on set; he was meticulous in his vision. His scripts were famous for charting every detail from the costumes to the angles that would be used. Even so, Ray improvised some of Pather Panchali ’s most beautiful and memorable images: the shot of the water spiders, a shot of the train smoke against the sunlight in the distance, and a climactic scene where Apu throws a necklace into a pond. The necklace was the topic of an argument between Durga’s mother and a neighbor woman, who accuses Durga of stealing it. After his sister’s death, Apu finds the necklace among her things. In the film’s most heartrending passage, Apu resolves to discard the evidence in a nearby pond. The algae slowly conceals the location of the necklace’s splash, as if sealing off his sister’s secret in his memory.

John Flaus described Pather Panchali as “an act of sublimity” for its closeness with Nature and natural human behavior—the way it appears less determined by formal approaches than the feelings and relationships of people in the natural world, far removed from the affectations or pretenses of commercial filmmaking. Ray’s observations are indeed extensive, capturing daily life on the Bengali countryside from beyond a directed perspective, beyond the child’s point-of-view that is often associated with the film. His camera witnesses things Apu does not, such as the slow decline of Auntie or Sarbajaya’s worry for her family, and in that, Ray helps his audience realize that empathy is not bound by class, national borders, races, or cultures. Curiously, Ray later received criticism for adopting Western styles, formal touches, and narrative structures in his work, suggesting his own output could hardly be called purely Indian, given the significant amount of influence he took from other filmmakers throughout the world. Many critics and scholars have used this quality about his films to pinpoint their universality to the human experience; others see it as a result of the lasting influence of British colonialism left on Indian culture. Given his influence from filmmakers around the world and his distinctly Indian subjects, Ray’s output remains unique among all others. Pather Panchali , more than its social significance within Indian culture, film history, or even Ray’s oeuvre, endures because, quite simply, Ray captures the beauty of the human condition.

Bibliography:

Dissanayake, Wimal. “Rethinking Indian Popular Cinema Towards Newer Frames of Understanding” Rethinking Third Cinema . Gunerante, Anthony R., and Wimal Dissanayake, editors. Routledge, 2003.

Ganguly, Keya. Cinema, Emergence, and the Films of Satyajit Ray . University of California Press, 2010.

Flaus, John. “The World of Satyajit Ray.” Senses of Cinema , no. 72, Oct. 2014, pp. 1-13.

Ray, Satyajit and Sandip Ray. Satyajit Ray on Cinema . Columbia University Press, 2011.

Ray, Satyajit. On Cinema . Ananda Pubs, 1982.

—. Our Films Their Films . Orient Longman, 1976.

Robinson, Andrew. Satyajit Ray: The Inner Eye . Second Edition, I.B. Tauris, 2004.

Roy, Binayak. “Ray: The Last Phase.” Film International , vol. 10, no. 2, June 2012, pp. 42-52.

Sengoopta, Chandak. “‘The Fruits of Independence’: Satyajit Ray, Indian Nationhood and the Spectre of Empire.” South Asian History and Culture , vol. 2, no. 3, 01 July 2011, p. 374-396.

—. “‘The Universal Film for All of Us, Everywhere in the World’: Satyajit Ray’s Pather Panchali (1955) and the Shadow of Robert Flaherty.” Historical Journal of Film , Radio & Television, vol. 29, no. 3, Sept. 2009, pp. 277-293.

Related Titles

- In Theaters

Recent Reviews

- Furiosa: A Mad Max Saga 4 Stars ☆ ☆ ☆ ☆

- Patreon Exclusive: The Strangers: Chapter 1 1 Star ☆

- Babes 3 Stars ☆ ☆ ☆

- Evil Does Not Exist 4 Stars ☆ ☆ ☆ ☆

- Coma 3.5 Stars ☆ ☆ ☆ ☆

- Nightwatch: Demons Are Forever 3.5 Stars ☆ ☆ ☆ ☆

- I Saw the TV Glow 3 Stars ☆ ☆ ☆

- The Last Stop in Yuma County 3 Stars ☆ ☆ ☆

- Back to Black 1.5 Stars ☆ ☆

- Stress Positions 2 Stars ☆ ☆

- Kingdom of the Planet of the Apes 3 Stars ☆ ☆ ☆

- Humane 3 Stars ☆ ☆ ☆

- Short Take: Unfrosted 1.5 Stars ☆ ☆

- The Fall Guy 2.5 Stars ☆ ☆ ☆

- The Idea of You 3 Stars ☆ ☆ ☆

Recent Articles

- Guest Appearance: The LAMBcast - The Fall Guy

- The Definitives: Paris, Texas

- Reader's Choice: Saturday Night Fever

- MSPIFF 2024 – Dispatch 4

- MSPIFF 2024 – Dispatch 3

- Guest Appearance: KARE 11 - 3 movies you need to see in theaters now

- MSPIFF 2024 – Dispatch 2

- Reader's Choice: Birth/Rebirth

- MSPIFF 2024 – Dispatch 1

- MSPIFF 2024

- Cast & crew

- User reviews

Pather Panchali

Impoverished priest Harihar Ray, dreaming of a better life for himself and his family, leaves his rural Bengal village in search of work. Impoverished priest Harihar Ray, dreaming of a better life for himself and his family, leaves his rural Bengal village in search of work. Impoverished priest Harihar Ray, dreaming of a better life for himself and his family, leaves his rural Bengal village in search of work.

- Satyajit Ray

- Bibhutibhushan Bandyopadhyay

- Kanu Bannerjee

- Karuna Bannerjee

- Subir Banerjee

- 201 User reviews

- 127 Critic reviews

- 11 wins & 2 nominations total

- Harihar Ray

- (as Kanu Bandyopadhyay)

- Sarbojaya Ray

- (as Karuna Bandopadhyay)

- (as Subir Bandopadhyay)

- Indir Thakrun

- (as Uma Dasgupta)

- Little Durga

- (as Runki Bandopadhyay)

- Seja Thakrun

- Nilmoni's wife

- Prasanna, school teacher

- Chinibas, Sweet-seller

- (as Haren Bandyopadhyay)

- Dasi Thakurun

- Ranu Mookerjee

- (as Rama Gangopadhyay)

- Baidyanath Majumdar

- (as Binoy Mukhopadhyay)

- All cast & crew

- Production, box office & more at IMDbPro

More like this

Did you know

- Trivia Halfway through filming, Ray ran out of funds. The Government of West Bengal loaned him the rest, allowing him to complete the film. This loan is listed in public records at the time as "roads improvement", a nod to the film's translated title.

- Goofs Although the film is set in early 20th-century rural India (a time in which public health campaigns presumably did not exist), when Apu and Durga are shown hiding in the fields waiting to catch a glimpse of the train, a vaccination mark is clearly visible on the right arm of Uma Das Gupta , who portrays Durga.

Durga : Come close.

Apu : What?

Durga : We'll go see the train when I'm better, all right? We'll get there early and have a good look. You want to?

- Alternate versions There is an Italian edition of this film on DVD, re-edited with the contribution of film historian Riccardo Cusin. This version is also available for streaming on some platforms.

- Connections Featured in Century of Cinema: And the Show Goes On: Indian Chapter (1996)

- Soundtracks It's A Long Way to Tipperary (uncredited) Written by Jack Judge and Harry Williams Played by the band

User reviews 201

- prince_corum

- May 4, 2005

- How long is Pather Panchali? Powered by Alexa

- What relation are the actors?

- August 26, 1955 (India)

- Watch on KLiKK

- Pather Panchali: Song of the Little Road

- Boral, West Bengal, India (entire movie)

- Government of West Bengal

- See more company credits at IMDbPro

- May 10, 2015

Technical specs

- Runtime 2 hours 5 minutes

- Black and White

Related news

Contribute to this page.

- See more gaps

- Learn more about contributing

More to explore

Recently viewed

Skip to main content

- Life & style

- Environment

Pather Panchali

Awesome, you're subscribed!

Thanks for subscribing! Look out for your first newsletter in your inbox soon!

The best things in life are free.

Sign up for our email to enjoy your city without spending a thing (as well as some options when you’re feeling flush).

Déjà vu! We already have this email. Try another?

By entering your email address you agree to our Terms of Use and Privacy Policy and consent to receive emails from Time Out about news, events, offers and partner promotions.

Love the mag?

Our newsletter hand-delivers the best bits to your inbox. Sign up to unlock our digital magazines and also receive the latest news, events, offers and partner promotions.

- Things to Do

- Food & Drink

- Arts & Culture

- Time Out Market

- Coca-Cola Foodmarks

- Los Angeles

Get us in your inbox

🙌 Awesome, you're subscribed!

Pather Panchali

Time Out says

Release details.

- Duration: 115 mins

Cast and crew

- Director: Satyajit Ray

- Screenwriter: Satyajit Ray

- Kanu Bannerjee

- Karuna Bannerjee

- Uma Das Gupta

- Subir Bannerjee

- Chunibala Devi

An email you’ll actually love

Discover Time Out original video

- Press office

- Investor relations

- Work for Time Out

- Editorial guidelines

- Privacy notice

- Do not sell my information

- Cookie policy

- Accessibility statement

- Terms of use

- Modern slavery statement

- Manage cookies

- Advertising

Time Out Worldwide

- All Time Out Locations

- North America

- South America

- South Pacific

- Skip to main content

- Access keys help

The first film in Satyajit Ray's famous Apu Trilogy, Pathar Panchali (Songs Of The Little Road) is the saga of an impoverished Brahmin family living in a small Bengali village. Taking the hero Apu through his early years up to adolescence, Ray's haunting and evocative debut feature helped redefine Indian cinema and place it firmly on the map of world cinema. Re-released to mark its 50th anniversary, this undisputed classic should not be missed.

When his father Harihar (Kanu Banerjee) leaves for the city to pursue his dream of becoming a playwright, young Apu (Subir Banerjee), his mother Sarbajaya (Karuna Banerjee) and mischievous sister Durga (Uma Das Gupta) are left to fend for themselves. With little money for food and clothing, the additional burden of looking after their independent spirited elderly aunt Indir (Chunibala Devi) leaves them struggling to make both ends meet. But there's no trace of melodrama in this tale as happiness, play and exploration uplift the children's daily life, projecting a family full of dignity not deficiency.

"TOUCHING IN ITS SIMPLICITY"

Adapted from Bibhutibhushan Bandyopadhyay's 1929 novel, and deeply rooted in Bengali culture, what makes Pathar Panchali universally appealing is that the story is essentially about human beings. Extremely touching in its simplicity, emotional range and visual beauty, it's no wonder it became the first Indian film to achieve widespread international acclaim and establish Ray as a master filmmaker. One viewing of this masterpiece half a century after its celluloid birth and you can see precisely why iconic Japanese filmmaker Akira Kurosawa remarked: "Not to have seen the cinema of Ray means existing in the world without seeing the sun or the moon."

In Bengali with English subtitles

End Credits

Cinema Search

New Releases

Find anything you save across the site in your account

Pather Panchali

By Pauline Kael

This first film by the masterly Satyajit Ray—possibly the most unembarrassed and natural of directors—is a quiet reverie about the life of an impoverished Brahman family in a Bengali village. Beautiful, sometimes funny, and full of love, it brought a new vision of India to the screen. Though the central characters are the boy Apu (who is born near the beginning) and his mother and father and sister, the character who makes the strongest impression on you may be the ancient, parasitic, storytelling relative, played by the eighty-year-old Chunibala Devi, a performer who apparently enjoyed coming back into the limelight after thirty years of obscurity. As Auntie, she is so remarkably likable that you may find the relationship between her and the mother, who is trying to feed her children and worries about how much the old lady eats, very painful. Released in 1955. In Bengali. (Film Forum; May 8-19)

Pather Panchali (India, 1955)

When discussing "giants" of the non-English-speaking, international film world, four names leap immediately to mind: Ingmar Bergman, Federico Fellini, Akira Kurosawa, and Satyajit Ray. Of these men, Ray has received the least North American exposure, but, arguably, the most critical acclaim. Praise for the Indian director, who died in 1992 shortly after receiving a lifetime achievement Oscar, has been effusive from both film makers and critics. Vincent Canby, of the New York Times , once wrote that "an entire world is evoked" by each of Ray's films. The late Louis Malle called Ray's body of work "magical and completely unique." And James Ivory, the director of Howards End and The Remains of the Day , has said that, after watching a Ray movie, the viewer will feel "fulfilled, enriched, maybe wiser, and wanting more."

Indeed, it is Ivory, along with his partner, Ismail Merchant, who has made this screening of Pather Panchali , Ray's directorial debut, possible. With financial backing from Sony Pictures Classics, Merchant and Ivory have cleaned up, packaged, and released a series of Ray pictures for distribution in select United States theaters. Included in "The Masterworks of Satyajit Ray" is the complete Apu Trilogy , which is comprised of three of the director's early films: Pather Panchali, Aparajito , and The World of Apu . The movies, which exist on video but are not readily available, are worth searching out. Anyone who believes in the uplifting power of motion pictures will not be disappointed.

Pather Panchali , Ray's first foray into the film making world, was completed in 1955, and proceeded to win the top prize at the 1956 Cannes Film Festival. It's a quiet, simple tale, centering on the life of a small family living in a rural village in Bengal. The father, Harihar (Kanu Bannerjee), is a priest and poet who cares more about his writing and spiritual welfare than obtaining wages he is owed. The mother, Sarbojaya (Karuna Bannerjee), worries that her husband's financial laxity will leave her without enough food for her two children, daughter Durga (Uma Das Gupta) and son Apu (Chunibala Devi). Harihar's family often lives on the edge of poverty, coping with the unkind taunts of their neighbors, the burden of caring for an aging aunt (Chunibala Devi), and the terrible aftermath of a natural catastrophe.

Pather Panchali starts slowly, but builds inexorably towards a powerful climax as we come to know, and empathize with, the characters. Ray takes the time to create a meticulously believable world that draws the viewer in. There isn't a false note in the entire film -- not in the characterization, the dialogue, or the storyline. The emotions evoked by the events of Pather Panchali are honest and true, not the contrived byproducts of manipulative formulas. Ray makes us feel with the characters, not just for them.

Most of what transpires is shown through the eyes of either Sarbojaya or Durga, and, as a result, we identify most closely with these two. Harihar is absent for more than half of the movie, and, before the penultimate scene, Apu is a mere witness to events, rather than a participant. Until the closing moments, we don't get a sense of the young boy as a fully formed individual, since he's always in someone else's shadow.

With its often-poetic black-and-white images and heartfelt method of storytelling, Pather Panchali speaks intimately to each member of the audience. This tale, as crafted by Ray, touches the souls and minds of viewers, transcending cultural and linguistic barriers. The languorous pace, which initially seems detrimental, proves to be an asset -- Pather Panchali would not have been the same experience had material been cut. Each scene builds upon what has come before. This is the kind of motion picture that will stay with you for hours, or perhaps even days, after you've left the theater, and that's a rare characteristic for any movie.

Comments Add Comment

- Cider House Rules, The (1999)

- Citizen Kane (1941)

- War Zone, The (1999)

- Hole in My Heart, A (2005)

- Neon Demon, The (2016)

- Showgirls (1995)

- Aparajito (1969)

- (There are no more better movies of Kanu Bannerjee)

- (There are no more worst movies of Kanu Bannerjee)

- (There are no more better movies of Karuna Bannerjee)

- (There are no more worst movies of Karuna Bannerjee)

- (There are no more better movies of Subir Bannerjee)

- (There are no more worst movies of Subir Bannerjee)

Pather Panchali

- Blu-ray edition reviewed by Chris Galloway

- December 08 2015

See more details, packaging, or compare

With the release in 1955 of Satyajit Ray’s debut, Pather Panchali , an eloquent and important new cinematic voice made itself heard all over the world. A depiction of rural Bengali life in a style inspired by Italian neorealism, this naturalistic but poetic evocation of a number of years in the life of a family introduces us to both little Apu and, just as essentially, the women who will help shape him: his independent older sister, Durga; his harried mother, Sarbajaya, who, with her husband away, must hold the family together; and his kindly and mischievous elderly “auntie,” Indir—vivid, multifaceted characters all. With resplendent photography informed by its young protagonist’s perpetual sense of discovery, Pather Panchali , which won an award for Best Human Document at Cannes, is an immersive cinematic experience and a film of elemental power.

Picture 8/10

Extras 6/10

You Might Like

Pather Panchali (Blu-ray/4K UHD Blu-ray)

Aparajito (Blu-ray)

Aparajito (Blu-ray/4K UHD Blu-ray)

Reviews by someone who's seen the movie

Pather Panchali

One of the breakout hits of world cinema – a term that didn’t yet exist – Pather Panchali came seemingly from nowhere in 1955 and swept all before it. It remains a highly regarded film to this day, still featuring on Sight and Sound ’s prestigious once-a-decade 100 Greatest Films of All Time list. In other words it’s one of those films you really ought to have seen if you’re going to hold your held high in the world of film buffery.

It’s part of director Satyajit Ray’s Apu trilogy, along with Aparajito (1956) and The World of Apu (1959), the three films forming a Bildungsroman slab of biographical drama centred on the child Apu, who is maybe eight years old as Pather Panchali gets underway.

Bildungsroman is another way of saying there isn’t really much of a story. You watch as you might watch a soap opera on TV, hooked to the characters, who are an engaging bunch – slightly ineffectual, incurably optimistic dad (Kanu Bannerjee), worried sick mum (Karuna Bannnerjee), sparkly, magpie-like daughter Durga (Uma Das Gupta) and big-eyed Mowgli-like Apu (Subir Bannerjee). This dirt-poor family has lost its orchard (dad’s fault, it’s suggested) and so struggles to feed themselves and their permanent guest, Indir, aka “Auntie” (Chunibala Devi). The rest of the village looks down on them. They’re not outsiders, or Untouchables or anything like that, just poor – they’re a family whose grip on existence is loose.

It’s a remarkable film in many respects not least the fact that almost everyone involved was fresh to the game. It was Satyajit Ray’s first film as a director – he’d worked as a location scout for an encouraging Jean Renoir when Renoir was filming The River in India – the cast were mostly amateurs, the crew was composed of rookies. Even the DP (Subrata Mitra) was making his debut, which makes the images he got in the can all the more remarkable.

One exception was “Auntie”, aka Chunibala Devi, a seasoned actress whom Ray coaxed out of a long retirement in her 80s to play the crook-backed, toothless Indir. She’d be dead before the film was shown publicly, but what a brilliant presence Auntie is, scurrying about, feral, naughty, smarter then she’s letting on and in many ways the soul of the film.

It’s a storyboarded film rather than a scripted one, relying on strong images to get its message across. They’re often beautifully composed and brilliantly lit, sometimes stark, sometimes almost liltingly bucolic, like when the two children run through a field full of feathery white seed heads, the low sun setting them aflame as the kids try to catch a glimpse of a passing steam train, an effect heightened by Ravi Shankar’s sensitive sitar.

The magic moments are offset with tragedy – there is death, and not entirely where you might expect it – which helps to give a shape to a film that’s been accused of being rambling, which was entirely what Ray was after. He’d been greatly influenced by seeing Vittorio De Sica’s Italian neorealist The Bicycle Thieves as part of a massive movie-binge while on a business trip in London (he worked in advertising at the time) and it shows.

Prepare to be enchanted rather than gripped, in other words. Accusations that Ray has prettified poverty do hold some weight, though that’s just at the level of image. As the narrative makes clear repeatedly – as the mother sells the last of the family’s valuable to buy rice, for example – the family’s whole existence is in the balance.

Look closely and you can spot that the kids are older in some scenes than other – the film took three years to make on account of lack of money – and the Criterion Collection version I watched does allow for a good close look. Remarkable when you consider that the original negative was damaged in a fire and some extreme technical innovation was required to “rehydrate” it. Even so, there are woolly images here and there, where the original was too far gone and second or possibly even third generation copies have been used as source material for the 4K scan.

They don’t ruin the enjoyment of a film that’s a milestone achievement.

Pather Panchali – watch it/buy it at Amazon

I am an Amazon affiliate

© Steve Morrissey 2021

Leave a Comment Cancel reply

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

IMDb information

- February 2024

- January 2024

- December 2023

- November 2023

- October 2023

- September 2023

- August 2023

- February 2023

- January 2023

- December 2022

- November 2022

- October 2022

- September 2022

- August 2022

- February 2022

- January 2022

- December 2021

- November 2021

- October 2021

- September 2021

- August 2021

- February 2021

- January 2021

- December 2020

- November 2020

- October 2020

- September 2020

- February 2020

- January 2020

- December 2019

- October 2019

- September 2019

- August 2019

- February 2019

- January 2019

- August 2018

- February 2018

- January 2018

- December 2017

- November 2017

- September 2017

- August 2017

- November 2016

- September 2016

- August 2016

- February 2016

- January 2016

- December 2015

- November 2015

- October 2015

- September 2015

- August 2015

- February 2015

- January 2015

- December 2014

- November 2014

- October 2014

- September 2014

- August 2014

- February 2014

- January 2014

- December 2013

- November 2013

- October 2013

- September 2013

- August 2013

- February 2013

- January 2013

- December 2012

- November 2012

- October 2012

- September 2012

- February 2012

- January 2012

- December 2011

- February 2011

- January 2009

- January 2007

- October 2006

- August 2006

- February 2002

- September 2000

[imdb]tt0048473[/imdb]

Join or Sign In

Sign in to customize your TV listings

By joining TV Guide, you agree to our Terms of Use and acknowledge the data practices in our Privacy Policy .

- TV Listings

- Cast & Crew

Pather Panchali Reviews

- 2 hr 2 mins

- Drama, Family

- Watchlist Where to Watch

This first film in Satyajit Ray's Apu trilogy uncovers beauty in the everyday lives of a struggling Bengalese family that includes a would-be writer, his wife, their two children and an aging aunt, all facing poverty and a barren future.

Satyajit Ray's debut film, and the first installment in his "Apu Trilogy," quietly and intently studies a family living in the grip of poverty in a Bengal village. This was the first film of a great body of work characterized by visual beauty, humor, and emotional generosity, and announced the arrival of a major new director on the world scene, as well as the debut of Indian cinema in the West. The father, a struggling writer, sets off to seek his fortune in the city, leaving his wife to take care of the children and an elderly aunt. Mere survival is a struggle for the poor family and the mother worries about how much the old lady eats. What follows is a series of perfectly ordinary events with a cumulative emotional power which may make some western viewers forever question the way Hollywood tells our stories. It's a powerful, unforgettable experience to watch characters whose lives are so different from our own, but whose concerns are ultimately universal. The remaining two films of the trilogy, APARAJITO and THE WORLD OF APU, follow the son, Apu (here played by Subir Banerjee), into manhood and fatherhood. Commissioned in 1945 to illustrate a children's version of the popular novel Pather Panchali, Ray became interested in bringing the novel to the screen, even though he had no previous film experience (nor did most of his crew). The production began sporadically on weekends, and was often interrupted by cash shortages before the Bengal government helped finish the picture. Like all Ray's best films, PATHER PANCHALI is influenced by the work of Jean Renoir (Ray visited the set of THE RIVER during its production in India) and of the Italian neorealists.

‘Pather Panchali’: The Greatest Indian Film Ever Made

“You can resist an invading army; you cannot resist an idea whose time has come” and so remarked Victor Marie Hugo, the renowned nineteenth-century French litterateur. Nothing else could better describe Satyajit Ray’s timeless classic ‘Pather Panchali’ (1955) or ‘The Song of the Road’, as it is known to the English-speaking world. Come to think of it, Ray didn’t have enough funds to complete the movie and he had to resort to desperate measures to finish filming. To make matters decidedly worse, his cinematographer Subrata Mitra was devoid of any real experience with the camera. Adding fuel to the fire, there were strict deadlines to be adhered to and to top it all, the film’s cast and crew were absolutely raw. In other words, the project was jinxed from the beginning itself. The production process consumed three years and there were many other hiccups along the way. However, the movie did get released and boy was it something!

Some called it a drag; others accused the film of exporting Indian poverty while there were many who dubbed it incomplete. Notwithstanding, ‘Pather Panchali’ firmly stands as a cinematic landmark in its own right – a work of art that changed the Indian cinemascape forever. What is the movie all about? To put it in a nutshell, it is about an impoverished family and the trivialities of daily life. Sounds simple! It is simple enough as life actually seems simple if looked at from an uncomplicated perspective. Somebody had it bang on when he said that simplicity is the most complicated business. Never before had an auteur delved so deep into the dynamics and redundancies of daily life and in such a profoundly humane fashion. The film was distinctly influenced by Italian Neorealism . At its core, ‘Pather Panchali’ proves that poverty doesn’t take away the little bundles of joy that life bestows on us.

If we were to analyze the movie in greater detail, we would find that it is more about Apu, the youngest member of the family and the son of Harihar Roy and Sarbajaya Roy. However, the tale would be left incomplete without the mention of Apu’s elder sister Durga, who acts like the thread holding the film together. While Harihar is struggling to make a living in a modest village in undivided Bengal of the 1920s, Sarbajaya seems to be eternally unhappy with the constricted ways of life that she has to endure. One of the most interesting characters in the film is the old and washed-up Indir Thakrun, who is apparently a burden on the family.

It is pertinent to note that there is something intrinsically lyrical about the plot, something that permeates all throughout the movie despite the obvious lack of drama that Ray concocted to translate realism on screen. The pronounced effect of Vittorio De Sica’s masterpiece ‘Bicycle Thieves’ (1948) could be clearly spotted if the film’s overall diegesis is considered from an objective point of view. We need to remember that Ray decided to become a filmmaker only after he had seen the Italian movie during a visit to London earlier.

‘Pather Panchali’ is also representative of childhood simplicity in more ways than one. The legendary scene where Apu and Durga are seen gazing at a train is a metaphor for a better future and things to come. The siblings are seen to take pleasure in rather simple things. One watch and it becomes crystal clear that Ray is trying to recreate the idyllic village life on screen, something that became non-existent after the partition of India. Based on a novel of the same name by successful Bengal novelist Bibhutibhushan Bandyopadhyay, ‘Pather Panchali’ is actually the first part of a trilogy that traces the life of Apu at three different periods in time in his life.

Drawing its inspiration from real life, the movie is beset with multiple tragic moments, recounted in a calm yet clear fashion. The demise of Indir Thakrun is thematically linked to the untimely death of Durga. The linkage, in a way, establishes the perishability of human life. While the passing away of Indir is nondescript and unceremonious, Durga dies on a turbulent night while making her family members understand the fright of death. All these happen when Harihar is away trying to make his way through poverty and provisioning for a better future. When he comes back, Sarbajaya breaks into tears at his feet. The scene is enough to evoke a feeling of helplessness that runs as a subtext.

While we marvel at Ray’s unique yet powerful way of storytelling, we become parts of a lost world that existed years ago. It is a miracle that we share many things with a setting that has hardly anything in common with our daily existence. Therein lays the beauty of good cinema where time and place no longer constitute barriers. If we look closely, we would find that there is something poetic about ‘Pather Panchali’, not so much for its portrayal of life in its crudest form but for rekindling the appreciation for those little things in life that we had forgotten years back. In a way, the movie takes us on a personal journey – a journey that leads us to a point of self-realization.

It seriously helps when we have a stalwart of Ravi Shankar’s caliber scoring the soundtrack of the movie. Now considered to be one of the finest background scores to have ever been composed, the music perfectly complements the somber mood. Shot mostly on location, a silent serenity marks the setting and makes it more authentic. The maverick mode of editing accomplished by the rookie Dulal Dutta would go down the annals of cinematic history as a novel style. When released, the film was at once loved and hated. However, over a period of time, it has managed to gather a significant fan base.

The iconic film critic Roger Ebert perfectly sums up the movie when he says, “The great, sad, gentle sweep of ‘The Apu Trilogy’ remains in the mind of the moviegoer as a promise of what film can be.” Indeed, ‘Pather Panchali’ is a promise that Ray made to his spectators – a promise that he was able to keep in the truest sense of the term.

SPONSORED LINKS

- Movie Explainers

- TV Explainers

- About The Cinemaholic

Pather Panchali Review

03 May 2002

111 minutes

Pather Panchali

So you think Star Wars is the best trilogy ever made? Watch Satyajit Ray's directorial debut (then follow up with its sequels, Aparajito and Apur Sansar) and you might reconsider.

Pather Panchali is indeed an Indian film, but in its black-and-white simplicity and documentary-style approach, it's closer to the Italian neorealist school that gave us Bicycle Thieves.

Ray captures the rhythms of life in a poor, rural village in minute detail, filtering family experiences through the eyes of a young boy.

Realism and idealism sit side by side in the dust, but the latter is never crushed by the former, and the overall effect is one of great beauty and humanity.

Movie Reviews Simbasible

- FILM DECADES

- MOVIE REVIEWS

Pather Panchali (1955)

…………………………………………………

Pather Panchali Movie Review

Pather Panchali is a Bengali drama film directed by Satyajit Ray . It is regularly cited as one of the best films of all time. In my opinion, it is quite good, but far from great.

………………………………………………….

“ Can’t an old woman have wishes too? “

The film basically depicts the harsh village life of one Bengali poor family during the 1910s . So the movie is definitely an important viewing for those unfamiliar with Third World suffering. I was familiar, but I certainly needed a reminder and the movie did that job really well. It succeeds as a very strong, moving drama that should prove relatable to anyone living in poor conditions or in a small village.

The characterization is solid, but definitely not great. That is fine as the film relied on storytelling and atmosphere more, but I still wanted more memorable characters. Harihar should have received more screen time, Sarbajaya is memorable as well as Durga but Apu is entirely underutilized and forgettable as the protagonist. Indir as this very old aunt is the highlight as her suffering is the most heartbreaking in the movie.

Pather Panchali is technically effective. Satyajit Ray’s direction is definitely superb, especially for a first-time director. It is confident and he showed evident talent for storytelling and social commentary. The same goes for the acting. These are for the most part amateur actors but you don’t see that as everybody did a really good job in their roles which is commendable. They also seemed like real people.

It is also gorgeously shot and scored. I loved its cinematography and the imagery of their village, the dilapidated houses as well as the forest was excellent and it transported you to its time period and setting remarkably well. The score is also fittingly Indian and classical in its tone with the use of more instruments than one which added some variety to the whole experience.

Pather Panchali is in my opinion overly slow and that is its biggest detractor. Some of the final scenes tended to veer too much into melodrama, but overall the emotional connection was there and the film succeeded in terms of plot and characterization. But it is just too slow, especially in some of its middle parts and those dragged the entire film unfortunately. It needed more drama and momentum.

Pather Panchali is overly slow, especially in its middle parts, and thus it is not fantastic in my opinion. But still it is a moving, important look at Indian poverty with some quite heartbreaking moments, very good acting, confident direction and particularly effective cinematography and score which transport you to its time period and setting remarkably well.

My Rating – 4

More stories, the red shoes (1948), challengers (2024), godzilla minus one (2023), leave a reply cancel reply.

Your email address will not be published.

You may have missed

The Plague (1947)

- Donald Duck

The Riveter (1940)

His dark materials season 3 (2022).

- Woody Woodpecker

The Dippy Diplomat (1945)

- Review Library

- Why I’m Wrong

Pather Panchali

Pather Panchali is truly one of the most delicate, humble and deeply felt movies I’ve ever seen. It will wreck you, build you up, ennoble you and leave you in a daze. You know, sort of like life.

The first installment in director Satyajit Ray’s Apu trilogy, Pather Panchali is set in rural Bengal in the 1920s, where a small family – consisting of a stooped, older aunt; a worried, mindful mother; a dreamy, often absent father; a clever older sister; and a lively younger brother – scratch out a quiet life in the shadow of richer, more established neighbors. The movie opens with little Durga (Runki Banerjee), before her brother Apu has been born, stealing fruit from those neighbors and the subsequent shaming of her mother (Karuna Banerjee) for the act. Need, honor, shame – these will continue to be the themes that dominate the household as the years roll by.

As the unofficial name of the trilogy suggests, Apu (Subir Banerjee) will come to be the focus of the tale, and what a delightful introduction he gets. In hopes of avoiding school, Apu is hiding under a blanket and pretending to be asleep when his older sister (now played by Uma Das Gupta) slowly pulls the blanket away to reveal a close-up of his bright, playful eye. Those eyes will prove to be the movie’s spark, and your heart will rise and fall as you watch toil and trouble try to snuff them out.

The sibling relationship between Durga and Apu is the heart of the film, so simpatico are the young actors in their scenes of everyday intimacy. Ray’s camera captures their squabbles, games and moments of tenderness, whether they’re huddling together during a rainstorm or chasing after a man selling sweets – not because they have money to buy any, but because it’s better to at least be near the possibility of sweets than to live in a world completely devoid of them.

Need, honor, shame – these will continue to be the themes that dominate the household as the years roll by.

There is death in Pather Panchali , but for me the most wrenching scene is a slighter one that marks a monumental change in this brother-sister relationship. After Apu has taken something of Durga’s without asking, the two begin to bicker. Their mother separates them and tells Durga: “You’re too old for a toy box.” Their crestfallen faces suggest the significance of the line their mother has just drawn, between Apu’s childishness and Durga’s adolescence. She’s opened a devastating rift.

In this moment and others, Ray’s film is perfectly attuned to the universal rhythms of family life. There is a wonderful scene in which they are all gathered outside their meager home, Apu’s father (Kanu Banerjee) working on a story or poem while Apu aspirationally scribbles something next to him; the mother brushing Durga’s hair nearby; and aged auntie (Chunibala Devi) mending her shawl in the corner. The quiet domesticity is interrupted by the whistle of a faraway train (one of a few instances in which traditional life is invaded by modernity). The camera cuts to Apu, who immediately looks up, and the gleam of excited curiosity in his eyes tells us that he’s already, in some sense, begun to leave this nest.

That cut is representative of the way Ray’s camera is always where it needs to be – and in the way it needs to be there. He consistently puts us at the very heart of the family dynamic. The variety and intricacy of the camerawork is astonishing, especially considering Ray and cinematographer Subrata Mitra were new to filmmaking. Among their techniques is an insistent tracking shot as the father paces outside the home during Apu’s birth. Another is a prankish POV shot from inside a large jug as Apu pulls a gaggle of kittens from it. There’s even a swish pan during one of the mother and aunt’s frequent squabbles that suggests Ray is a key influence on Wes Anderson.

Ray and Mitra also make exquisite use of their rural setting. The sunlight is so plentiful, they must have only shot on the brightest of days. When smoke from cooking fires is added, the effect is otherworldly. The contrast to this idyllic scenery, of course, is the monsoon sequence, a drenching darkness that turns the figures on the screen into ghostly blurs. In the aftermath of this destruction, we come to understand just how closely to the edge Apu’s family has been living. If the movie leaves you emotionally drained, it’s because you’ve been living with them all along.

Sponsored by the following | become a sponsor

site categories

Conflict, cuts and identity crises: how film festivals are navigating choppy waters, breaking news.

Made In India: The World’s Biggest Film Industry Hasn’t Had A Film In The Cannes Competition Since 1994 … Until Now

Related stories.

Cannes Cover Story: Aubrey Plaza Says Francis Coppola “Doesn’t Need My Defense”, Reveals The “Collaboration And Experimentation” Of ‘Megalopolis’

Deepika Padukone On Bringing Indian Cinema To Hollywood, Tackling Mental Health Taboos And Helping Underrepresented Communities

This included India, with Chetan Anand’s social-realist drama Neecha Nagar , and, for a decade at least, the country was a regular fixture in Competition. After Anand came V. Shantaram with Amar Bhoopali (1952), then Raj Kapoor with Awaara (1953), and Bimal Roy with Do Bigha Zamin (1954). But the film that put India on the map in Cannes was the debut feature by director Satyajit Ray, whose film Pather Panchali — the first of his now-famous ‘Apu Trilogy’ — was championed by prime minister Jawaharlal Nehru and won the one-off honor of Best Human Document. After Ray’s Devi in 1962, however, the run was broken, and, for a while, it seemed that Shaji N. Karun’s Swaham (1994), a Malayalam-language drama, might be the last Indian film ever to play in competition.

But now India is about to break its 30-year hiatus with Mumbai-based filmmaker Payal Kapadia’s ambitious fiction feature debut All We Imagine As Light . Shot over 25 late summer days in Mumbai, followed by an extra 15 in the rainy western port town of Ratnagiri, the Malayalam-Hindi language feature tells the story of two young women — Prabha, a nurse from Mumbai, and Anu, her roommate. A rare French-Indo co-production, it is a collaboration between the Paris-based producers Thomas Hakim and Julien Graff, of petit chaos, and Zico Maitra of Chalk & Cheese Films out of Mumbai.

“I met Payal in 2018 at the Berlinale where she was presenting her short film And What is the Summer Saying ,” Hakim says as he sneaks away from the editing suite where he and Kapadia are completing their final cut. “As we were living in different parts of the world, it didn’t seem like were meant to meet or work together. But I felt a deep connection with her cinema as if we were speaking a common language.”

Hakim says European development funds like Rotterdam’s Hubert Bals grant, and the Cannes Cinéfondation Residency, allowed Kapadia to reside in Europe, where they could develop their joint practice before mounting the ambitious production in her native India. “The French and European funding system, through CNC, Eurimages, the Gan Foundation, Cineworld, Visions Sud Est, and Hubert Bals, along with private partners like Arte, Luxbox, Condor, and Pulpa Film allowed us to gather the financing and shoot the entire film in India, with a 99% Indian cast and crew,” he adds. “In the process, it was important that this co-production stayed organic and didn’t alter Payal’s vision with unnecessary constraints.”

An alumnus of the state-run Film and Television Institute of India (FTII), Kapadia has history at Cannes. In 2017, she screened Afternoon Clouds , a 13-minute project, as part of the festival’s Cinéfondation shorts sidebar. Her last film, the non-fiction project A Night of Knowing Nothing (2021), also produced by Hakim and Graff for petit chaos, screened in Director’s Fortnight, where it won the Golden Eye for best documentary.