The Research Hypothesis: Role and Construction

- First Online: 01 January 2012

Cite this chapter

- Phyllis G. Supino EdD 3

6021 Accesses

A hypothesis is a logical construct, interposed between a problem and its solution, which represents a proposed answer to a research question. It gives direction to the investigator’s thinking about the problem and, therefore, facilitates a solution. There are three primary modes of inference by which hypotheses are developed: deduction (reasoning from a general propositions to specific instances), induction (reasoning from specific instances to a general proposition), and abduction (formulation/acceptance on probation of a hypothesis to explain a surprising observation).

A research hypothesis should reflect an inference about variables; be stated as a grammatically complete, declarative sentence; be expressed simply and unambiguously; provide an adequate answer to the research problem; and be testable. Hypotheses can be classified as conceptual versus operational, single versus bi- or multivariable, causal or not causal, mechanistic versus nonmechanistic, and null or alternative. Hypotheses most commonly entail statements about “variables” which, in turn, can be classified according to their level of measurement (scaling characteristics) or according to their role in the hypothesis (independent, dependent, moderator, control, or intervening).

A hypothesis is rendered operational when its broadly (conceptually) stated variables are replaced by operational definitions of those variables. Hypotheses stated in this manner are called operational hypotheses, specific hypotheses, or predictions and facilitate testing.

Wrong hypotheses, rightly worked from, have produced more results than unguided observation

—Augustus De Morgan, 1872[ 1 ]—

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this chapter

- Available as EPUB and PDF

- Read on any device

- Instant download

- Own it forever

- Compact, lightweight edition

- Dispatched in 3 to 5 business days

- Free shipping worldwide - see info

- Durable hardcover edition

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Institutional subscriptions

De Morgan A, De Morgan S. A budget of paradoxes. London: Longmans Green; 1872.

Google Scholar

Leedy Paul D. Practical research. Planning and design. 2nd ed. New York: Macmillan; 1960.

Bernard C. Introduction to the study of experimental medicine. New York: Dover; 1957.

Erren TC. The quest for questions—on the logical force of science. Med Hypotheses. 2004;62:635–40.

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Peirce CS. Collected papers of Charles Sanders Peirce, vol. 7. In: Hartshorne C, Weiss P, editors. Boston: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press; 1966.

Aristotle. The complete works of Aristotle: the revised Oxford Translation. In: Barnes J, editor. vol. 2. Princeton/New Jersey: Princeton University Press; 1984.

Polit D, Beck CT. Conceptualizing a study to generate evidence for nursing. In: Polit D, Beck CT, editors. Nursing research: generating and assessing evidence for nursing practice. 8th ed. Philadelphia: Wolters Kluwer/Lippincott Williams and Wilkins; 2008. Chapter 4.

Jenicek M, Hitchcock DL. Evidence-based practice. Logic and critical thinking in medicine. Chicago: AMA Press; 2005.

Bacon F. The novum organon or a true guide to the interpretation of nature. A new translation by the Rev G.W. Kitchin. Oxford: The University Press; 1855.

Popper KR. Objective knowledge: an evolutionary approach (revised edition). New York: Oxford University Press; 1979.

Morgan AJ, Parker S. Translational mini-review series on vaccines: the Edward Jenner Museum and the history of vaccination. Clin Exp Immunol. 2007;147:389–94.

Article PubMed CAS Google Scholar

Pead PJ. Benjamin Jesty: new light in the dawn of vaccination. Lancet. 2003;362:2104–9.

Lee JA. The scientific endeavor: a primer on scientific principles and practice. San Francisco: Addison-Wesley Longman; 2000.

Allchin D. Lawson’s shoehorn, or should the philosophy of science be rated, ‘X’? Science and Education. 2003;12:315–29.

Article Google Scholar

Lawson AE. What is the role of induction and deduction in reasoning and scientific inquiry? J Res Sci Teach. 2005;42:716–40.

Peirce CS. Collected papers of Charles Sanders Peirce, vol. 2. In: Hartshorne C, Weiss P, editors. Boston: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press; 1965.

Bonfantini MA, Proni G. To guess or not to guess? In: Eco U, Sebeok T, editors. The sign of three: Dupin, Holmes, Peirce. Bloomington: Indiana University Press; 1983. Chapter 5.

Peirce CS. Collected papers of Charles Sanders Peirce, vol. 5. In: Hartshorne C, Weiss P, editors. Boston: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press; 1965.

Flach PA, Kakas AC. Abductive and inductive reasoning: background issues. In: Flach PA, Kakas AC, editors. Abduction and induction. Essays on their relation and integration. The Netherlands: Klewer; 2000. Chapter 1.

Murray JF. Voltaire, Walpole and Pasteur: variations on the theme of discovery. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2005;172:423–6.

Danemark B, Ekstrom M, Jakobsen L, Karlsson JC. Methodological implications, generalization, scientific inference, models (Part II) In: explaining society. Critical realism in the social sciences. New York: Routledge; 2002.

Pasteur L. Inaugural lecture as professor and dean of the faculty of sciences. In: Peterson H, editor. A treasury of the world’s greatest speeches. Douai, France: University of Lille 7 Dec 1954.

Swineburne R. Simplicity as evidence for truth. Milwaukee: Marquette University Press; 1997.

Sakar S, editor. Logical empiricism at its peak: Schlick, Carnap and Neurath. New York: Garland; 1996.

Popper K. The logic of scientific discovery. New York: Basic Books; 1959. 1934, trans. 1959.

Caws P. The philosophy of science. Princeton: D. Van Nostrand Company; 1965.

Popper K. Conjectures and refutations. The growth of scientific knowledge. 4th ed. London: Routledge and Keegan Paul; 1972.

Feyerabend PK. Against method, outline of an anarchistic theory of knowledge. London, UK: Verso; 1978.

Smith PG. Popper: conjectures and refutations (Chapter IV). In: Theory and reality: an introduction to the philosophy of science. Chicago: University of Chicago Press; 2003.

Blystone RV, Blodgett K. WWW: the scientific method. CBE Life Sci Educ. 2006;5:7–11.

Kleinbaum DG, Kupper LL, Morgenstern H. Epidemiological research. Principles and quantitative methods. New York: Van Nostrand Reinhold; 1982.

Fortune AE, Reid WJ. Research in social work. 3rd ed. New York: Columbia University Press; 1999.

Kerlinger FN. Foundations of behavioral research. 1st ed. New York: Hold, Reinhart and Winston; 1970.

Hoskins CN, Mariano C. Research in nursing and health. Understanding and using quantitative and qualitative methods. New York: Springer; 2004.

Tuckman BW. Conducting educational research. New York: Harcourt, Brace, Jovanovich; 1972.

Wang C, Chiari PC, Weihrauch D, Krolikowski JG, Warltier DC, Kersten JR, Pratt Jr PF, Pagel PS. Gender-specificity of delayed preconditioning by isoflurane in rabbits: potential role of endothelial nitric oxide synthase. Anesth Analg. 2006;103:274–80.

Beyer ME, Slesak G, Nerz S, Kazmaier S, Hoffmeister HM. Effects of endothelin-1 and IRL 1620 on myocardial contractility and myocardial energy metabolism. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol. 1995;26(Suppl 3):S150–2.

PubMed CAS Google Scholar

Stone J, Sharpe M. Amnesia for childhood in patients with unexplained neurological symptoms. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2002;72:416–7.

Naughton BJ, Moran M, Ghaly Y, Michalakes C. Computer tomography scanning and delirium in elder patients. Acad Emerg Med. 1997;4:1107–10.

Easterbrook PJ, Berlin JA, Gopalan R, Matthews DR. Publication bias in clinical research. Lancet. 1991;337:867–72.

Stern JM, Simes RJ. Publication bias: evidence of delayed publication in a cohort study of clinical research projects. BMJ. 1997;315:640–5.

Stevens SS. On the theory of scales and measurement. Science. 1946;103:677–80.

Knapp TR. Treating ordinal scales as interval scales: an attempt to resolve the controversy. Nurs Res. 1990;39:121–3.

The Cochrane Collaboration. Open Learning Material. www.cochrane-net.org/openlearning/html/mod14-3.htm . Accessed 12 Oct 2009.

MacCorquodale K, Meehl PE. On a distinction between hypothetical constructs and intervening variables. Psychol Rev. 1948;55:95–107.

Baron RM, Kenny DA. The moderator-mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: conceptual, strategic and statistical considerations. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1986;51:1173–82.

Williamson GM, Schultz R. Activity restriction mediates the association between pain and depressed affect: a study of younger and older adult cancer patients. Psychol Aging. 1995;10:369–78.

Song M, Lee EO. Development of a functional capacity model for the elderly. Res Nurs Health. 1998;21:189–98.

MacKinnon DP. Introduction to statistical mediation analysis. New York: Routledge; 2008.

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Department of Medicine, College of Medicine, SUNY Downstate Medical Center, 450 Clarkson Avenue, 1199, Brooklyn, NY, 11203, USA

Phyllis G. Supino EdD

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Phyllis G. Supino EdD .

Editor information

Editors and affiliations.

, Cardiovascular Medicine, SUNY Downstate Medical Center, Clarkson Avenue, box 1199 450, Brooklyn, 11203, USA

Phyllis G. Supino

, Cardiovascualr Medicine, SUNY Downstate Medical Center, Clarkson Avenue 450, Brooklyn, 11203, USA

Jeffrey S. Borer

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

Copyright information

© 2012 Springer Science+Business Media, LLC

About this chapter

Supino, P.G. (2012). The Research Hypothesis: Role and Construction. In: Supino, P., Borer, J. (eds) Principles of Research Methodology. Springer, New York, NY. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4614-3360-6_3

Download citation

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4614-3360-6_3

Published : 18 April 2012

Publisher Name : Springer, New York, NY

Print ISBN : 978-1-4614-3359-0

Online ISBN : 978-1-4614-3360-6

eBook Packages : Medicine Medicine (R0)

Share this chapter

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

- Skip to main content

- Skip to primary sidebar

- Skip to footer

- QuestionPro

- Solutions Industries Gaming Automotive Sports and events Education Government Travel & Hospitality Financial Services Healthcare Cannabis Technology Use Case NPS+ Communities Audience Contactless surveys Mobile LivePolls Member Experience GDPR Positive People Science 360 Feedback Surveys

- Resources Blog eBooks Survey Templates Case Studies Training Help center

Home Market Research

Research Hypothesis: What It Is, Types + How to Develop?

A research study starts with a question. Researchers worldwide ask questions and create research hypotheses. The effectiveness of research relies on developing a good research hypothesis. Examples of research hypotheses can guide researchers in writing effective ones.

In this blog, we’ll learn what a research hypothesis is, why it’s important in research, and the different types used in science. We’ll also guide you through creating your research hypothesis and discussing ways to test and evaluate it.

What is a Research Hypothesis?

A hypothesis is like a guess or idea that you suggest to check if it’s true. A research hypothesis is a statement that brings up a question and predicts what might happen.

It’s really important in the scientific method and is used in experiments to figure things out. Essentially, it’s an educated guess about how things are connected in the research.

A research hypothesis usually includes pointing out the independent variable (the thing they’re changing or studying) and the dependent variable (the result they’re measuring or watching). It helps plan how to gather and analyze data to see if there’s evidence to support or deny the expected connection between these variables.

Importance of Hypothesis in Research

Hypotheses are really important in research. They help design studies, allow for practical testing, and add to our scientific knowledge. Their main role is to organize research projects, making them purposeful, focused, and valuable to the scientific community. Let’s look at some key reasons why they matter:

- A research hypothesis helps test theories.

A hypothesis plays a pivotal role in the scientific method by providing a basis for testing existing theories. For example, a hypothesis might test the predictive power of a psychological theory on human behavior.

- It serves as a great platform for investigation activities.

It serves as a launching pad for investigation activities, which offers researchers a clear starting point. A research hypothesis can explore the relationship between exercise and stress reduction.

- Hypothesis guides the research work or study.

A well-formulated hypothesis guides the entire research process. It ensures that the study remains focused and purposeful. For instance, a hypothesis about the impact of social media on interpersonal relationships provides clear guidance for a study.

- Hypothesis sometimes suggests theories.

In some cases, a hypothesis can suggest new theories or modifications to existing ones. For example, a hypothesis testing the effectiveness of a new drug might prompt a reconsideration of current medical theories.

- It helps in knowing the data needs.

A hypothesis clarifies the data requirements for a study, ensuring that researchers collect the necessary information—a hypothesis guiding the collection of demographic data to analyze the influence of age on a particular phenomenon.

- The hypothesis explains social phenomena.

Hypotheses are instrumental in explaining complex social phenomena. For instance, a hypothesis might explore the relationship between economic factors and crime rates in a given community.

- Hypothesis provides a relationship between phenomena for empirical Testing.

Hypotheses establish clear relationships between phenomena, paving the way for empirical testing. An example could be a hypothesis exploring the correlation between sleep patterns and academic performance.

- It helps in knowing the most suitable analysis technique.

A hypothesis guides researchers in selecting the most appropriate analysis techniques for their data. For example, a hypothesis focusing on the effectiveness of a teaching method may lead to the choice of statistical analyses best suited for educational research.

Characteristics of a Good Research Hypothesis

A hypothesis is a specific idea that you can test in a study. It often comes from looking at past research and theories. A good hypothesis usually starts with a research question that you can explore through background research. For it to be effective, consider these key characteristics:

- Clear and Focused Language: A good hypothesis uses clear and focused language to avoid confusion and ensure everyone understands it.

- Related to the Research Topic: The hypothesis should directly relate to the research topic, acting as a bridge between the specific question and the broader study.

- Testable: An effective hypothesis can be tested, meaning its prediction can be checked with real data to support or challenge the proposed relationship.

- Potential for Exploration: A good hypothesis often comes from a research question that invites further exploration. Doing background research helps find gaps and potential areas to investigate.

- Includes Variables: The hypothesis should clearly state both the independent and dependent variables, specifying the factors being studied and the expected outcomes.

- Ethical Considerations: Check if variables can be manipulated without breaking ethical standards. It’s crucial to maintain ethical research practices.

- Predicts Outcomes: The hypothesis should predict the expected relationship and outcome, acting as a roadmap for the study and guiding data collection and analysis.

- Simple and Concise: A good hypothesis avoids unnecessary complexity and is simple and concise, expressing the essence of the proposed relationship clearly.

- Clear and Assumption-Free: The hypothesis should be clear and free from assumptions about the reader’s prior knowledge, ensuring universal understanding.

- Observable and Testable Results: A strong hypothesis implies research that produces observable and testable results, making sure the study’s outcomes can be effectively measured and analyzed.

When you use these characteristics as a checklist, it can help you create a good research hypothesis. It’ll guide improving and strengthening the hypothesis, identifying any weaknesses, and making necessary changes. Crafting a hypothesis with these features helps you conduct a thorough and insightful research study.

Types of Research Hypotheses

The research hypothesis comes in various types, each serving a specific purpose in guiding the scientific investigation. Knowing the differences will make it easier for you to create your own hypothesis. Here’s an overview of the common types:

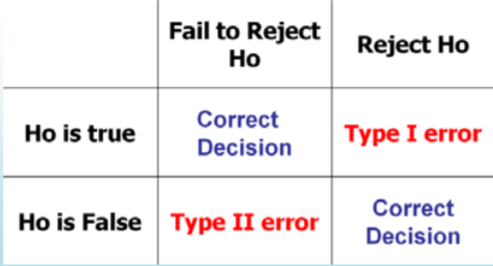

01. Null Hypothesis

The null hypothesis states that there is no connection between two considered variables or that two groups are unrelated. As discussed earlier, a hypothesis is an unproven assumption lacking sufficient supporting data. It serves as the statement researchers aim to disprove. It is testable, verifiable, and can be rejected.

For example, if you’re studying the relationship between Project A and Project B, assuming both projects are of equal standard is your null hypothesis. It needs to be specific for your study.

02. Alternative Hypothesis

The alternative hypothesis is basically another option to the null hypothesis. It involves looking for a significant change or alternative that could lead you to reject the null hypothesis. It’s a different idea compared to the null hypothesis.

When you create a null hypothesis, you’re making an educated guess about whether something is true or if there’s a connection between that thing and another variable. If the null view suggests something is correct, the alternative hypothesis says it’s incorrect.

For instance, if your null hypothesis is “I’m going to be $1000 richer,” the alternative hypothesis would be “I’m not going to get $1000 or be richer.”

03. Directional Hypothesis

The directional hypothesis predicts the direction of the relationship between independent and dependent variables. They specify whether the effect will be positive or negative.

If you increase your study hours, you will experience a positive association with your exam scores. This hypothesis suggests that as you increase the independent variable (study hours), there will also be an increase in the dependent variable (exam scores).

04. Non-directional Hypothesis

The non-directional hypothesis predicts the existence of a relationship between variables but does not specify the direction of the effect. It suggests that there will be a significant difference or relationship, but it does not predict the nature of that difference.

For example, you will find no notable difference in test scores between students who receive the educational intervention and those who do not. However, once you compare the test scores of the two groups, you will notice an important difference.

05. Simple Hypothesis

A simple hypothesis predicts a relationship between one dependent variable and one independent variable without specifying the nature of that relationship. It’s simple and usually used when we don’t know much about how the two things are connected.

For example, if you adopt effective study habits, you will achieve higher exam scores than those with poor study habits.

06. Complex Hypothesis

A complex hypothesis is an idea that specifies a relationship between multiple independent and dependent variables. It is a more detailed idea than a simple hypothesis.

While a simple view suggests a straightforward cause-and-effect relationship between two things, a complex hypothesis involves many factors and how they’re connected to each other.

For example, when you increase your study time, you tend to achieve higher exam scores. The connection between your study time and exam performance is affected by various factors, including the quality of your sleep, your motivation levels, and the effectiveness of your study techniques.

If you sleep well, stay highly motivated, and use effective study strategies, you may observe a more robust positive correlation between the time you spend studying and your exam scores, unlike those who may lack these factors.

07. Associative Hypothesis

An associative hypothesis proposes a connection between two things without saying that one causes the other. Basically, it suggests that when one thing changes, the other changes too, but it doesn’t claim that one thing is causing the change in the other.

For example, you will likely notice higher exam scores when you increase your study time. You can recognize an association between your study time and exam scores in this scenario.

Your hypothesis acknowledges a relationship between the two variables—your study time and exam scores—without asserting that increased study time directly causes higher exam scores. You need to consider that other factors, like motivation or learning style, could affect the observed association.

08. Causal Hypothesis

A causal hypothesis proposes a cause-and-effect relationship between two variables. It suggests that changes in one variable directly cause changes in another variable.

For example, when you increase your study time, you experience higher exam scores. This hypothesis suggests a direct cause-and-effect relationship, indicating that the more time you spend studying, the higher your exam scores. It assumes that changes in your study time directly influence changes in your exam performance.

09. Empirical Hypothesis

An empirical hypothesis is a statement based on things we can see and measure. It comes from direct observation or experiments and can be tested with real-world evidence. If an experiment proves a theory, it supports the idea and shows it’s not just a guess. This makes the statement more reliable than a wild guess.

For example, if you increase the dosage of a certain medication, you might observe a quicker recovery time for patients. Imagine you’re in charge of a clinical trial. In this trial, patients are given varying dosages of the medication, and you measure and compare their recovery times. This allows you to directly see the effects of different dosages on how fast patients recover.

This way, you can create a research hypothesis: “Increasing the dosage of a certain medication will lead to a faster recovery time for patients.”

10. Statistical Hypothesis

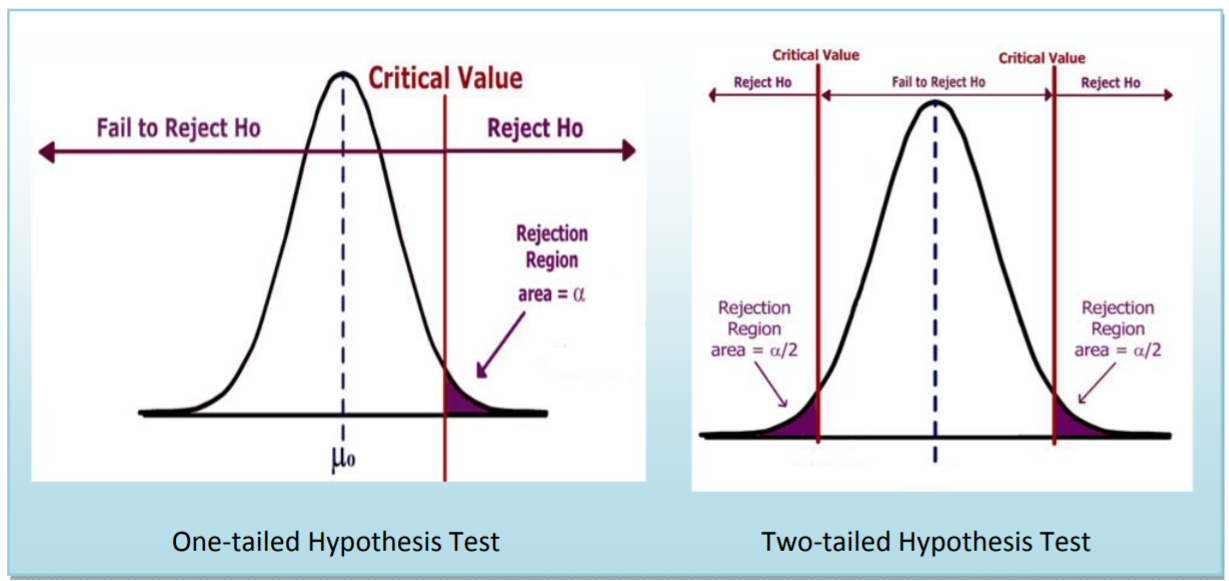

A statistical hypothesis is a statement or assumption about a population parameter that is the subject of an investigation. It serves as the basis for statistical analysis and testing. It is often tested using statistical methods to draw inferences about the larger population.

In a hypothesis test, statistical evidence is collected to either reject the null hypothesis in favor of the alternative hypothesis or fail to reject the null hypothesis due to insufficient evidence.

For example, let’s say you’re testing a new medicine. Your hypothesis could be that the medicine doesn’t really help patients get better. So, you collect data and use statistics to see if your guess is right or if the medicine actually makes a difference.

If the data strongly shows that the medicine does help, you say your guess was wrong, and the medicine does make a difference. But if the proof isn’t strong enough, you can stick with your original guess because you didn’t get enough evidence to change your mind.

How to Develop a Research Hypotheses?

Step 1: identify your research problem or topic..

Define the area of interest or the problem you want to investigate. Make sure it’s clear and well-defined.

Start by asking a question about your chosen topic. Consider the limitations of your research and create a straightforward problem related to your topic. Once you’ve done that, you can develop and test a hypothesis with evidence.

Step 2: Conduct a literature review

Review existing literature related to your research problem. This will help you understand the current state of knowledge in the field, identify gaps, and build a foundation for your hypothesis. Consider the following questions:

- What existing research has been conducted on your chosen topic?

- Are there any gaps or unanswered questions in the current literature?

- How will the existing literature contribute to the foundation of your research?

Step 3: Formulate your research question

Based on your literature review, create a specific and concise research question that addresses your identified problem. Your research question should be clear, focused, and relevant to your field of study.

Step 4: Identify variables

Determine the key variables involved in your research question. Variables are the factors or phenomena that you will study and manipulate to test your hypothesis.

- Independent Variable: The variable you manipulate or control.

- Dependent Variable: The variable you measure to observe the effect of the independent variable.

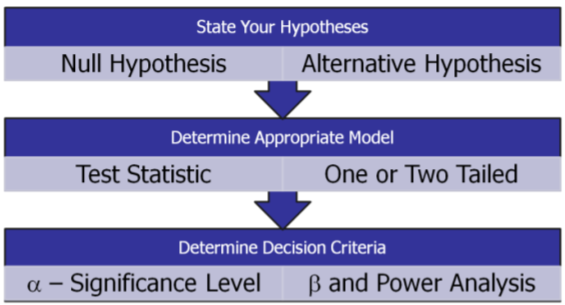

Step 5: State the Null hypothesis

The null hypothesis is a statement that there is no significant difference or effect. It serves as a baseline for comparison with the alternative hypothesis.

Step 6: Select appropriate methods for testing the hypothesis

Choose research methods that align with your study objectives, such as experiments, surveys, or observational studies. The selected methods enable you to test your research hypothesis effectively.

Creating a research hypothesis usually takes more than one try. Expect to make changes as you collect data. It’s normal to test and say no to a few hypotheses before you find the right answer to your research question.

Testing and Evaluating Hypotheses

Testing hypotheses is a really important part of research. It’s like the practical side of things. Here, real-world evidence will help you determine how different things are connected. Let’s explore the main steps in hypothesis testing:

- State your research hypothesis.

Before testing, clearly articulate your research hypothesis. This involves framing both a null hypothesis, suggesting no significant effect or relationship, and an alternative hypothesis, proposing the expected outcome.

- Collect data strategically.

Plan how you will gather information in a way that fits your study. Make sure your data collection method matches the things you’re studying.

Whether through surveys, observations, or experiments, this step demands precision and adherence to the established methodology. The quality of data collected directly influences the credibility of study outcomes.

- Perform an appropriate statistical test.

Choose a statistical test that aligns with the nature of your data and the hypotheses being tested. Whether it’s a t-test, chi-square test, ANOVA, or regression analysis, selecting the right statistical tool is paramount for accurate and reliable results.

- Decide if your idea was right or wrong.

Following the statistical analysis, evaluate the results in the context of your null hypothesis. You need to decide if you should reject your null hypothesis or not.

- Share what you found.

When discussing what you found in your research, be clear and organized. Say whether your idea was supported or not, and talk about what your results mean. Also, mention any limits to your study and suggest ideas for future research.

The Role of QuestionPro to Develop a Good Research Hypothesis

QuestionPro is a survey and research platform that provides tools for creating, distributing, and analyzing surveys. It plays a crucial role in the research process, especially when you’re in the initial stages of hypothesis development. Here’s how QuestionPro can help you to develop a good research hypothesis:

- Survey design and data collection: You can use the platform to create targeted questions that help you gather relevant data.

- Exploratory research: Through surveys and feedback mechanisms on QuestionPro, you can conduct exploratory research to understand the landscape of a particular subject.

- Literature review and background research: QuestionPro surveys can collect sample population opinions, experiences, and preferences. This data and a thorough literature evaluation can help you generate a well-grounded hypothesis by improving your research knowledge.

- Identifying variables: Using targeted survey questions, you can identify relevant variables related to their research topic.

- Testing assumptions: You can use surveys to informally test certain assumptions or hypotheses before formalizing a research hypothesis.

- Data analysis tools: QuestionPro provides tools for analyzing survey data. You can use these tools to identify the collected data’s patterns, correlations, or trends.

- Refining your hypotheses: As you collect data through QuestionPro, you can adjust your hypotheses based on the real-world responses you receive.

A research hypothesis is like a guide for researchers in science. It’s a well-thought-out idea that has been thoroughly tested. This idea is crucial as researchers can explore different fields, such as medicine, social sciences, and natural sciences. The research hypothesis links theories to real-world evidence and gives researchers a clear path to explore and make discoveries.

QuestionPro Research Suite is a helpful tool for researchers. It makes creating surveys, collecting data, and analyzing information easily. It supports all kinds of research, from exploring new ideas to forming hypotheses. With a focus on using data, it helps researchers do their best work.

Are you interested in learning more about QuestionPro Research Suite? Take advantage of QuestionPro’s free trial to get an initial look at its capabilities and realize the full potential of your research efforts.

LEARN MORE FREE TRIAL

MORE LIKE THIS

I Am Disconnected – Tuesday CX Thoughts

May 21, 2024

20 Best Customer Success Tools of 2024

May 20, 2024

AI-Based Services Buying Guide for Market Research (based on ESOMAR’s 20 Questions)

Data Information vs Insight: Essential differences

May 14, 2024

Other categories

- Academic Research

- Artificial Intelligence

- Assessments

- Brand Awareness

- Case Studies

- Communities

- Consumer Insights

- Customer effort score

- Customer Engagement

- Customer Experience

- Customer Loyalty

- Customer Research

- Customer Satisfaction

- Employee Benefits

- Employee Engagement

- Employee Retention

- Friday Five

- General Data Protection Regulation

- Insights Hub

- Life@QuestionPro

- Market Research

- Mobile diaries

- Mobile Surveys

- New Features

- Online Communities

- Question Types

- Questionnaire

- QuestionPro Products

- Release Notes

- Research Tools and Apps

- Revenue at Risk

- Survey Templates

- Training Tips

- Uncategorized

- Video Learning Series

- What’s Coming Up

- Workforce Intelligence

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- J Korean Med Sci

- v.37(16); 2022 Apr 25

A Practical Guide to Writing Quantitative and Qualitative Research Questions and Hypotheses in Scholarly Articles

Edward barroga.

1 Department of General Education, Graduate School of Nursing Science, St. Luke’s International University, Tokyo, Japan.

Glafera Janet Matanguihan

2 Department of Biological Sciences, Messiah University, Mechanicsburg, PA, USA.

The development of research questions and the subsequent hypotheses are prerequisites to defining the main research purpose and specific objectives of a study. Consequently, these objectives determine the study design and research outcome. The development of research questions is a process based on knowledge of current trends, cutting-edge studies, and technological advances in the research field. Excellent research questions are focused and require a comprehensive literature search and in-depth understanding of the problem being investigated. Initially, research questions may be written as descriptive questions which could be developed into inferential questions. These questions must be specific and concise to provide a clear foundation for developing hypotheses. Hypotheses are more formal predictions about the research outcomes. These specify the possible results that may or may not be expected regarding the relationship between groups. Thus, research questions and hypotheses clarify the main purpose and specific objectives of the study, which in turn dictate the design of the study, its direction, and outcome. Studies developed from good research questions and hypotheses will have trustworthy outcomes with wide-ranging social and health implications.

INTRODUCTION

Scientific research is usually initiated by posing evidenced-based research questions which are then explicitly restated as hypotheses. 1 , 2 The hypotheses provide directions to guide the study, solutions, explanations, and expected results. 3 , 4 Both research questions and hypotheses are essentially formulated based on conventional theories and real-world processes, which allow the inception of novel studies and the ethical testing of ideas. 5 , 6

It is crucial to have knowledge of both quantitative and qualitative research 2 as both types of research involve writing research questions and hypotheses. 7 However, these crucial elements of research are sometimes overlooked; if not overlooked, then framed without the forethought and meticulous attention it needs. Planning and careful consideration are needed when developing quantitative or qualitative research, particularly when conceptualizing research questions and hypotheses. 4

There is a continuing need to support researchers in the creation of innovative research questions and hypotheses, as well as for journal articles that carefully review these elements. 1 When research questions and hypotheses are not carefully thought of, unethical studies and poor outcomes usually ensue. Carefully formulated research questions and hypotheses define well-founded objectives, which in turn determine the appropriate design, course, and outcome of the study. This article then aims to discuss in detail the various aspects of crafting research questions and hypotheses, with the goal of guiding researchers as they develop their own. Examples from the authors and peer-reviewed scientific articles in the healthcare field are provided to illustrate key points.

DEFINITIONS AND RELATIONSHIP OF RESEARCH QUESTIONS AND HYPOTHESES

A research question is what a study aims to answer after data analysis and interpretation. The answer is written in length in the discussion section of the paper. Thus, the research question gives a preview of the different parts and variables of the study meant to address the problem posed in the research question. 1 An excellent research question clarifies the research writing while facilitating understanding of the research topic, objective, scope, and limitations of the study. 5

On the other hand, a research hypothesis is an educated statement of an expected outcome. This statement is based on background research and current knowledge. 8 , 9 The research hypothesis makes a specific prediction about a new phenomenon 10 or a formal statement on the expected relationship between an independent variable and a dependent variable. 3 , 11 It provides a tentative answer to the research question to be tested or explored. 4

Hypotheses employ reasoning to predict a theory-based outcome. 10 These can also be developed from theories by focusing on components of theories that have not yet been observed. 10 The validity of hypotheses is often based on the testability of the prediction made in a reproducible experiment. 8

Conversely, hypotheses can also be rephrased as research questions. Several hypotheses based on existing theories and knowledge may be needed to answer a research question. Developing ethical research questions and hypotheses creates a research design that has logical relationships among variables. These relationships serve as a solid foundation for the conduct of the study. 4 , 11 Haphazardly constructed research questions can result in poorly formulated hypotheses and improper study designs, leading to unreliable results. Thus, the formulations of relevant research questions and verifiable hypotheses are crucial when beginning research. 12

CHARACTERISTICS OF GOOD RESEARCH QUESTIONS AND HYPOTHESES

Excellent research questions are specific and focused. These integrate collective data and observations to confirm or refute the subsequent hypotheses. Well-constructed hypotheses are based on previous reports and verify the research context. These are realistic, in-depth, sufficiently complex, and reproducible. More importantly, these hypotheses can be addressed and tested. 13

There are several characteristics of well-developed hypotheses. Good hypotheses are 1) empirically testable 7 , 10 , 11 , 13 ; 2) backed by preliminary evidence 9 ; 3) testable by ethical research 7 , 9 ; 4) based on original ideas 9 ; 5) have evidenced-based logical reasoning 10 ; and 6) can be predicted. 11 Good hypotheses can infer ethical and positive implications, indicating the presence of a relationship or effect relevant to the research theme. 7 , 11 These are initially developed from a general theory and branch into specific hypotheses by deductive reasoning. In the absence of a theory to base the hypotheses, inductive reasoning based on specific observations or findings form more general hypotheses. 10

TYPES OF RESEARCH QUESTIONS AND HYPOTHESES

Research questions and hypotheses are developed according to the type of research, which can be broadly classified into quantitative and qualitative research. We provide a summary of the types of research questions and hypotheses under quantitative and qualitative research categories in Table 1 .

Research questions in quantitative research

In quantitative research, research questions inquire about the relationships among variables being investigated and are usually framed at the start of the study. These are precise and typically linked to the subject population, dependent and independent variables, and research design. 1 Research questions may also attempt to describe the behavior of a population in relation to one or more variables, or describe the characteristics of variables to be measured ( descriptive research questions ). 1 , 5 , 14 These questions may also aim to discover differences between groups within the context of an outcome variable ( comparative research questions ), 1 , 5 , 14 or elucidate trends and interactions among variables ( relationship research questions ). 1 , 5 We provide examples of descriptive, comparative, and relationship research questions in quantitative research in Table 2 .

Hypotheses in quantitative research

In quantitative research, hypotheses predict the expected relationships among variables. 15 Relationships among variables that can be predicted include 1) between a single dependent variable and a single independent variable ( simple hypothesis ) or 2) between two or more independent and dependent variables ( complex hypothesis ). 4 , 11 Hypotheses may also specify the expected direction to be followed and imply an intellectual commitment to a particular outcome ( directional hypothesis ) 4 . On the other hand, hypotheses may not predict the exact direction and are used in the absence of a theory, or when findings contradict previous studies ( non-directional hypothesis ). 4 In addition, hypotheses can 1) define interdependency between variables ( associative hypothesis ), 4 2) propose an effect on the dependent variable from manipulation of the independent variable ( causal hypothesis ), 4 3) state a negative relationship between two variables ( null hypothesis ), 4 , 11 , 15 4) replace the working hypothesis if rejected ( alternative hypothesis ), 15 explain the relationship of phenomena to possibly generate a theory ( working hypothesis ), 11 5) involve quantifiable variables that can be tested statistically ( statistical hypothesis ), 11 6) or express a relationship whose interlinks can be verified logically ( logical hypothesis ). 11 We provide examples of simple, complex, directional, non-directional, associative, causal, null, alternative, working, statistical, and logical hypotheses in quantitative research, as well as the definition of quantitative hypothesis-testing research in Table 3 .

Research questions in qualitative research

Unlike research questions in quantitative research, research questions in qualitative research are usually continuously reviewed and reformulated. The central question and associated subquestions are stated more than the hypotheses. 15 The central question broadly explores a complex set of factors surrounding the central phenomenon, aiming to present the varied perspectives of participants. 15

There are varied goals for which qualitative research questions are developed. These questions can function in several ways, such as to 1) identify and describe existing conditions ( contextual research question s); 2) describe a phenomenon ( descriptive research questions ); 3) assess the effectiveness of existing methods, protocols, theories, or procedures ( evaluation research questions ); 4) examine a phenomenon or analyze the reasons or relationships between subjects or phenomena ( explanatory research questions ); or 5) focus on unknown aspects of a particular topic ( exploratory research questions ). 5 In addition, some qualitative research questions provide new ideas for the development of theories and actions ( generative research questions ) or advance specific ideologies of a position ( ideological research questions ). 1 Other qualitative research questions may build on a body of existing literature and become working guidelines ( ethnographic research questions ). Research questions may also be broadly stated without specific reference to the existing literature or a typology of questions ( phenomenological research questions ), may be directed towards generating a theory of some process ( grounded theory questions ), or may address a description of the case and the emerging themes ( qualitative case study questions ). 15 We provide examples of contextual, descriptive, evaluation, explanatory, exploratory, generative, ideological, ethnographic, phenomenological, grounded theory, and qualitative case study research questions in qualitative research in Table 4 , and the definition of qualitative hypothesis-generating research in Table 5 .

Qualitative studies usually pose at least one central research question and several subquestions starting with How or What . These research questions use exploratory verbs such as explore or describe . These also focus on one central phenomenon of interest, and may mention the participants and research site. 15

Hypotheses in qualitative research

Hypotheses in qualitative research are stated in the form of a clear statement concerning the problem to be investigated. Unlike in quantitative research where hypotheses are usually developed to be tested, qualitative research can lead to both hypothesis-testing and hypothesis-generating outcomes. 2 When studies require both quantitative and qualitative research questions, this suggests an integrative process between both research methods wherein a single mixed-methods research question can be developed. 1

FRAMEWORKS FOR DEVELOPING RESEARCH QUESTIONS AND HYPOTHESES

Research questions followed by hypotheses should be developed before the start of the study. 1 , 12 , 14 It is crucial to develop feasible research questions on a topic that is interesting to both the researcher and the scientific community. This can be achieved by a meticulous review of previous and current studies to establish a novel topic. Specific areas are subsequently focused on to generate ethical research questions. The relevance of the research questions is evaluated in terms of clarity of the resulting data, specificity of the methodology, objectivity of the outcome, depth of the research, and impact of the study. 1 , 5 These aspects constitute the FINER criteria (i.e., Feasible, Interesting, Novel, Ethical, and Relevant). 1 Clarity and effectiveness are achieved if research questions meet the FINER criteria. In addition to the FINER criteria, Ratan et al. described focus, complexity, novelty, feasibility, and measurability for evaluating the effectiveness of research questions. 14

The PICOT and PEO frameworks are also used when developing research questions. 1 The following elements are addressed in these frameworks, PICOT: P-population/patients/problem, I-intervention or indicator being studied, C-comparison group, O-outcome of interest, and T-timeframe of the study; PEO: P-population being studied, E-exposure to preexisting conditions, and O-outcome of interest. 1 Research questions are also considered good if these meet the “FINERMAPS” framework: Feasible, Interesting, Novel, Ethical, Relevant, Manageable, Appropriate, Potential value/publishable, and Systematic. 14

As we indicated earlier, research questions and hypotheses that are not carefully formulated result in unethical studies or poor outcomes. To illustrate this, we provide some examples of ambiguous research question and hypotheses that result in unclear and weak research objectives in quantitative research ( Table 6 ) 16 and qualitative research ( Table 7 ) 17 , and how to transform these ambiguous research question(s) and hypothesis(es) into clear and good statements.

a These statements were composed for comparison and illustrative purposes only.

b These statements are direct quotes from Higashihara and Horiuchi. 16

a This statement is a direct quote from Shimoda et al. 17

The other statements were composed for comparison and illustrative purposes only.

CONSTRUCTING RESEARCH QUESTIONS AND HYPOTHESES

To construct effective research questions and hypotheses, it is very important to 1) clarify the background and 2) identify the research problem at the outset of the research, within a specific timeframe. 9 Then, 3) review or conduct preliminary research to collect all available knowledge about the possible research questions by studying theories and previous studies. 18 Afterwards, 4) construct research questions to investigate the research problem. Identify variables to be accessed from the research questions 4 and make operational definitions of constructs from the research problem and questions. Thereafter, 5) construct specific deductive or inductive predictions in the form of hypotheses. 4 Finally, 6) state the study aims . This general flow for constructing effective research questions and hypotheses prior to conducting research is shown in Fig. 1 .

Research questions are used more frequently in qualitative research than objectives or hypotheses. 3 These questions seek to discover, understand, explore or describe experiences by asking “What” or “How.” The questions are open-ended to elicit a description rather than to relate variables or compare groups. The questions are continually reviewed, reformulated, and changed during the qualitative study. 3 Research questions are also used more frequently in survey projects than hypotheses in experiments in quantitative research to compare variables and their relationships.

Hypotheses are constructed based on the variables identified and as an if-then statement, following the template, ‘If a specific action is taken, then a certain outcome is expected.’ At this stage, some ideas regarding expectations from the research to be conducted must be drawn. 18 Then, the variables to be manipulated (independent) and influenced (dependent) are defined. 4 Thereafter, the hypothesis is stated and refined, and reproducible data tailored to the hypothesis are identified, collected, and analyzed. 4 The hypotheses must be testable and specific, 18 and should describe the variables and their relationships, the specific group being studied, and the predicted research outcome. 18 Hypotheses construction involves a testable proposition to be deduced from theory, and independent and dependent variables to be separated and measured separately. 3 Therefore, good hypotheses must be based on good research questions constructed at the start of a study or trial. 12

In summary, research questions are constructed after establishing the background of the study. Hypotheses are then developed based on the research questions. Thus, it is crucial to have excellent research questions to generate superior hypotheses. In turn, these would determine the research objectives and the design of the study, and ultimately, the outcome of the research. 12 Algorithms for building research questions and hypotheses are shown in Fig. 2 for quantitative research and in Fig. 3 for qualitative research.

EXAMPLES OF RESEARCH QUESTIONS FROM PUBLISHED ARTICLES

- EXAMPLE 1. Descriptive research question (quantitative research)

- - Presents research variables to be assessed (distinct phenotypes and subphenotypes)

- “BACKGROUND: Since COVID-19 was identified, its clinical and biological heterogeneity has been recognized. Identifying COVID-19 phenotypes might help guide basic, clinical, and translational research efforts.

- RESEARCH QUESTION: Does the clinical spectrum of patients with COVID-19 contain distinct phenotypes and subphenotypes? ” 19

- EXAMPLE 2. Relationship research question (quantitative research)

- - Shows interactions between dependent variable (static postural control) and independent variable (peripheral visual field loss)

- “Background: Integration of visual, vestibular, and proprioceptive sensations contributes to postural control. People with peripheral visual field loss have serious postural instability. However, the directional specificity of postural stability and sensory reweighting caused by gradual peripheral visual field loss remain unclear.

- Research question: What are the effects of peripheral visual field loss on static postural control ?” 20

- EXAMPLE 3. Comparative research question (quantitative research)

- - Clarifies the difference among groups with an outcome variable (patients enrolled in COMPERA with moderate PH or severe PH in COPD) and another group without the outcome variable (patients with idiopathic pulmonary arterial hypertension (IPAH))

- “BACKGROUND: Pulmonary hypertension (PH) in COPD is a poorly investigated clinical condition.

- RESEARCH QUESTION: Which factors determine the outcome of PH in COPD?

- STUDY DESIGN AND METHODS: We analyzed the characteristics and outcome of patients enrolled in the Comparative, Prospective Registry of Newly Initiated Therapies for Pulmonary Hypertension (COMPERA) with moderate or severe PH in COPD as defined during the 6th PH World Symposium who received medical therapy for PH and compared them with patients with idiopathic pulmonary arterial hypertension (IPAH) .” 21

- EXAMPLE 4. Exploratory research question (qualitative research)

- - Explores areas that have not been fully investigated (perspectives of families and children who receive care in clinic-based child obesity treatment) to have a deeper understanding of the research problem

- “Problem: Interventions for children with obesity lead to only modest improvements in BMI and long-term outcomes, and data are limited on the perspectives of families of children with obesity in clinic-based treatment. This scoping review seeks to answer the question: What is known about the perspectives of families and children who receive care in clinic-based child obesity treatment? This review aims to explore the scope of perspectives reported by families of children with obesity who have received individualized outpatient clinic-based obesity treatment.” 22

- EXAMPLE 5. Relationship research question (quantitative research)

- - Defines interactions between dependent variable (use of ankle strategies) and independent variable (changes in muscle tone)

- “Background: To maintain an upright standing posture against external disturbances, the human body mainly employs two types of postural control strategies: “ankle strategy” and “hip strategy.” While it has been reported that the magnitude of the disturbance alters the use of postural control strategies, it has not been elucidated how the level of muscle tone, one of the crucial parameters of bodily function, determines the use of each strategy. We have previously confirmed using forward dynamics simulations of human musculoskeletal models that an increased muscle tone promotes the use of ankle strategies. The objective of the present study was to experimentally evaluate a hypothesis: an increased muscle tone promotes the use of ankle strategies. Research question: Do changes in the muscle tone affect the use of ankle strategies ?” 23

EXAMPLES OF HYPOTHESES IN PUBLISHED ARTICLES

- EXAMPLE 1. Working hypothesis (quantitative research)

- - A hypothesis that is initially accepted for further research to produce a feasible theory

- “As fever may have benefit in shortening the duration of viral illness, it is plausible to hypothesize that the antipyretic efficacy of ibuprofen may be hindering the benefits of a fever response when taken during the early stages of COVID-19 illness .” 24

- “In conclusion, it is plausible to hypothesize that the antipyretic efficacy of ibuprofen may be hindering the benefits of a fever response . The difference in perceived safety of these agents in COVID-19 illness could be related to the more potent efficacy to reduce fever with ibuprofen compared to acetaminophen. Compelling data on the benefit of fever warrant further research and review to determine when to treat or withhold ibuprofen for early stage fever for COVID-19 and other related viral illnesses .” 24

- EXAMPLE 2. Exploratory hypothesis (qualitative research)

- - Explores particular areas deeper to clarify subjective experience and develop a formal hypothesis potentially testable in a future quantitative approach

- “We hypothesized that when thinking about a past experience of help-seeking, a self distancing prompt would cause increased help-seeking intentions and more favorable help-seeking outcome expectations .” 25

- “Conclusion

- Although a priori hypotheses were not supported, further research is warranted as results indicate the potential for using self-distancing approaches to increasing help-seeking among some people with depressive symptomatology.” 25

- EXAMPLE 3. Hypothesis-generating research to establish a framework for hypothesis testing (qualitative research)

- “We hypothesize that compassionate care is beneficial for patients (better outcomes), healthcare systems and payers (lower costs), and healthcare providers (lower burnout). ” 26

- Compassionomics is the branch of knowledge and scientific study of the effects of compassionate healthcare. Our main hypotheses are that compassionate healthcare is beneficial for (1) patients, by improving clinical outcomes, (2) healthcare systems and payers, by supporting financial sustainability, and (3) HCPs, by lowering burnout and promoting resilience and well-being. The purpose of this paper is to establish a scientific framework for testing the hypotheses above . If these hypotheses are confirmed through rigorous research, compassionomics will belong in the science of evidence-based medicine, with major implications for all healthcare domains.” 26

- EXAMPLE 4. Statistical hypothesis (quantitative research)

- - An assumption is made about the relationship among several population characteristics ( gender differences in sociodemographic and clinical characteristics of adults with ADHD ). Validity is tested by statistical experiment or analysis ( chi-square test, Students t-test, and logistic regression analysis)

- “Our research investigated gender differences in sociodemographic and clinical characteristics of adults with ADHD in a Japanese clinical sample. Due to unique Japanese cultural ideals and expectations of women's behavior that are in opposition to ADHD symptoms, we hypothesized that women with ADHD experience more difficulties and present more dysfunctions than men . We tested the following hypotheses: first, women with ADHD have more comorbidities than men with ADHD; second, women with ADHD experience more social hardships than men, such as having less full-time employment and being more likely to be divorced.” 27

- “Statistical Analysis

- ( text omitted ) Between-gender comparisons were made using the chi-squared test for categorical variables and Students t-test for continuous variables…( text omitted ). A logistic regression analysis was performed for employment status, marital status, and comorbidity to evaluate the independent effects of gender on these dependent variables.” 27

EXAMPLES OF HYPOTHESIS AS WRITTEN IN PUBLISHED ARTICLES IN RELATION TO OTHER PARTS

- EXAMPLE 1. Background, hypotheses, and aims are provided

- “Pregnant women need skilled care during pregnancy and childbirth, but that skilled care is often delayed in some countries …( text omitted ). The focused antenatal care (FANC) model of WHO recommends that nurses provide information or counseling to all pregnant women …( text omitted ). Job aids are visual support materials that provide the right kind of information using graphics and words in a simple and yet effective manner. When nurses are not highly trained or have many work details to attend to, these job aids can serve as a content reminder for the nurses and can be used for educating their patients (Jennings, Yebadokpo, Affo, & Agbogbe, 2010) ( text omitted ). Importantly, additional evidence is needed to confirm how job aids can further improve the quality of ANC counseling by health workers in maternal care …( text omitted )” 28

- “ This has led us to hypothesize that the quality of ANC counseling would be better if supported by job aids. Consequently, a better quality of ANC counseling is expected to produce higher levels of awareness concerning the danger signs of pregnancy and a more favorable impression of the caring behavior of nurses .” 28

- “This study aimed to examine the differences in the responses of pregnant women to a job aid-supported intervention during ANC visit in terms of 1) their understanding of the danger signs of pregnancy and 2) their impression of the caring behaviors of nurses to pregnant women in rural Tanzania.” 28

- EXAMPLE 2. Background, hypotheses, and aims are provided

- “We conducted a two-arm randomized controlled trial (RCT) to evaluate and compare changes in salivary cortisol and oxytocin levels of first-time pregnant women between experimental and control groups. The women in the experimental group touched and held an infant for 30 min (experimental intervention protocol), whereas those in the control group watched a DVD movie of an infant (control intervention protocol). The primary outcome was salivary cortisol level and the secondary outcome was salivary oxytocin level.” 29

- “ We hypothesize that at 30 min after touching and holding an infant, the salivary cortisol level will significantly decrease and the salivary oxytocin level will increase in the experimental group compared with the control group .” 29

- EXAMPLE 3. Background, aim, and hypothesis are provided

- “In countries where the maternal mortality ratio remains high, antenatal education to increase Birth Preparedness and Complication Readiness (BPCR) is considered one of the top priorities [1]. BPCR includes birth plans during the antenatal period, such as the birthplace, birth attendant, transportation, health facility for complications, expenses, and birth materials, as well as family coordination to achieve such birth plans. In Tanzania, although increasing, only about half of all pregnant women attend an antenatal clinic more than four times [4]. Moreover, the information provided during antenatal care (ANC) is insufficient. In the resource-poor settings, antenatal group education is a potential approach because of the limited time for individual counseling at antenatal clinics.” 30

- “This study aimed to evaluate an antenatal group education program among pregnant women and their families with respect to birth-preparedness and maternal and infant outcomes in rural villages of Tanzania.” 30

- “ The study hypothesis was if Tanzanian pregnant women and their families received a family-oriented antenatal group education, they would (1) have a higher level of BPCR, (2) attend antenatal clinic four or more times, (3) give birth in a health facility, (4) have less complications of women at birth, and (5) have less complications and deaths of infants than those who did not receive the education .” 30

Research questions and hypotheses are crucial components to any type of research, whether quantitative or qualitative. These questions should be developed at the very beginning of the study. Excellent research questions lead to superior hypotheses, which, like a compass, set the direction of research, and can often determine the successful conduct of the study. Many research studies have floundered because the development of research questions and subsequent hypotheses was not given the thought and meticulous attention needed. The development of research questions and hypotheses is an iterative process based on extensive knowledge of the literature and insightful grasp of the knowledge gap. Focused, concise, and specific research questions provide a strong foundation for constructing hypotheses which serve as formal predictions about the research outcomes. Research questions and hypotheses are crucial elements of research that should not be overlooked. They should be carefully thought of and constructed when planning research. This avoids unethical studies and poor outcomes by defining well-founded objectives that determine the design, course, and outcome of the study.

Disclosure: The authors have no potential conflicts of interest to disclose.

Author Contributions:

- Conceptualization: Barroga E, Matanguihan GJ.

- Methodology: Barroga E, Matanguihan GJ.

- Writing - original draft: Barroga E, Matanguihan GJ.

- Writing - review & editing: Barroga E, Matanguihan GJ.

Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, automatically generate references for free.

- Knowledge Base

- Methodology

Research Design | Step-by-Step Guide with Examples

Published on 5 May 2022 by Shona McCombes . Revised on 20 March 2023.

A research design is a strategy for answering your research question using empirical data. Creating a research design means making decisions about:

- Your overall aims and approach

- The type of research design you’ll use

- Your sampling methods or criteria for selecting subjects

- Your data collection methods

- The procedures you’ll follow to collect data

- Your data analysis methods

A well-planned research design helps ensure that your methods match your research aims and that you use the right kind of analysis for your data.

Table of contents

Step 1: consider your aims and approach, step 2: choose a type of research design, step 3: identify your population and sampling method, step 4: choose your data collection methods, step 5: plan your data collection procedures, step 6: decide on your data analysis strategies, frequently asked questions.

- Introduction

Before you can start designing your research, you should already have a clear idea of the research question you want to investigate.

There are many different ways you could go about answering this question. Your research design choices should be driven by your aims and priorities – start by thinking carefully about what you want to achieve.

The first choice you need to make is whether you’ll take a qualitative or quantitative approach.

Qualitative research designs tend to be more flexible and inductive , allowing you to adjust your approach based on what you find throughout the research process.

Quantitative research designs tend to be more fixed and deductive , with variables and hypotheses clearly defined in advance of data collection.

It’s also possible to use a mixed methods design that integrates aspects of both approaches. By combining qualitative and quantitative insights, you can gain a more complete picture of the problem you’re studying and strengthen the credibility of your conclusions.

Practical and ethical considerations when designing research

As well as scientific considerations, you need to think practically when designing your research. If your research involves people or animals, you also need to consider research ethics .

- How much time do you have to collect data and write up the research?

- Will you be able to gain access to the data you need (e.g., by travelling to a specific location or contacting specific people)?

- Do you have the necessary research skills (e.g., statistical analysis or interview techniques)?

- Will you need ethical approval ?

At each stage of the research design process, make sure that your choices are practically feasible.

Prevent plagiarism, run a free check.

Within both qualitative and quantitative approaches, there are several types of research design to choose from. Each type provides a framework for the overall shape of your research.

Types of quantitative research designs

Quantitative designs can be split into four main types. Experimental and quasi-experimental designs allow you to test cause-and-effect relationships, while descriptive and correlational designs allow you to measure variables and describe relationships between them.

With descriptive and correlational designs, you can get a clear picture of characteristics, trends, and relationships as they exist in the real world. However, you can’t draw conclusions about cause and effect (because correlation doesn’t imply causation ).

Experiments are the strongest way to test cause-and-effect relationships without the risk of other variables influencing the results. However, their controlled conditions may not always reflect how things work in the real world. They’re often also more difficult and expensive to implement.

Types of qualitative research designs

Qualitative designs are less strictly defined. This approach is about gaining a rich, detailed understanding of a specific context or phenomenon, and you can often be more creative and flexible in designing your research.

The table below shows some common types of qualitative design. They often have similar approaches in terms of data collection, but focus on different aspects when analysing the data.

Your research design should clearly define who or what your research will focus on, and how you’ll go about choosing your participants or subjects.

In research, a population is the entire group that you want to draw conclusions about, while a sample is the smaller group of individuals you’ll actually collect data from.

Defining the population

A population can be made up of anything you want to study – plants, animals, organisations, texts, countries, etc. In the social sciences, it most often refers to a group of people.

For example, will you focus on people from a specific demographic, region, or background? Are you interested in people with a certain job or medical condition, or users of a particular product?

The more precisely you define your population, the easier it will be to gather a representative sample.

Sampling methods

Even with a narrowly defined population, it’s rarely possible to collect data from every individual. Instead, you’ll collect data from a sample.

To select a sample, there are two main approaches: probability sampling and non-probability sampling . The sampling method you use affects how confidently you can generalise your results to the population as a whole.

Probability sampling is the most statistically valid option, but it’s often difficult to achieve unless you’re dealing with a very small and accessible population.

For practical reasons, many studies use non-probability sampling, but it’s important to be aware of the limitations and carefully consider potential biases. You should always make an effort to gather a sample that’s as representative as possible of the population.

Case selection in qualitative research

In some types of qualitative designs, sampling may not be relevant.

For example, in an ethnography or a case study, your aim is to deeply understand a specific context, not to generalise to a population. Instead of sampling, you may simply aim to collect as much data as possible about the context you are studying.

In these types of design, you still have to carefully consider your choice of case or community. You should have a clear rationale for why this particular case is suitable for answering your research question.

For example, you might choose a case study that reveals an unusual or neglected aspect of your research problem, or you might choose several very similar or very different cases in order to compare them.

Data collection methods are ways of directly measuring variables and gathering information. They allow you to gain first-hand knowledge and original insights into your research problem.

You can choose just one data collection method, or use several methods in the same study.

Survey methods

Surveys allow you to collect data about opinions, behaviours, experiences, and characteristics by asking people directly. There are two main survey methods to choose from: questionnaires and interviews.

Observation methods

Observations allow you to collect data unobtrusively, observing characteristics, behaviours, or social interactions without relying on self-reporting.

Observations may be conducted in real time, taking notes as you observe, or you might make audiovisual recordings for later analysis. They can be qualitative or quantitative.

Other methods of data collection

There are many other ways you might collect data depending on your field and topic.

If you’re not sure which methods will work best for your research design, try reading some papers in your field to see what data collection methods they used.

Secondary data

If you don’t have the time or resources to collect data from the population you’re interested in, you can also choose to use secondary data that other researchers already collected – for example, datasets from government surveys or previous studies on your topic.

With this raw data, you can do your own analysis to answer new research questions that weren’t addressed by the original study.

Using secondary data can expand the scope of your research, as you may be able to access much larger and more varied samples than you could collect yourself.

However, it also means you don’t have any control over which variables to measure or how to measure them, so the conclusions you can draw may be limited.

As well as deciding on your methods, you need to plan exactly how you’ll use these methods to collect data that’s consistent, accurate, and unbiased.

Planning systematic procedures is especially important in quantitative research, where you need to precisely define your variables and ensure your measurements are reliable and valid.

Operationalisation

Some variables, like height or age, are easily measured. But often you’ll be dealing with more abstract concepts, like satisfaction, anxiety, or competence. Operationalisation means turning these fuzzy ideas into measurable indicators.

If you’re using observations , which events or actions will you count?

If you’re using surveys , which questions will you ask and what range of responses will be offered?

You may also choose to use or adapt existing materials designed to measure the concept you’re interested in – for example, questionnaires or inventories whose reliability and validity has already been established.

Reliability and validity

Reliability means your results can be consistently reproduced , while validity means that you’re actually measuring the concept you’re interested in.

For valid and reliable results, your measurement materials should be thoroughly researched and carefully designed. Plan your procedures to make sure you carry out the same steps in the same way for each participant.

If you’re developing a new questionnaire or other instrument to measure a specific concept, running a pilot study allows you to check its validity and reliability in advance.

Sampling procedures

As well as choosing an appropriate sampling method, you need a concrete plan for how you’ll actually contact and recruit your selected sample.

That means making decisions about things like:

- How many participants do you need for an adequate sample size?

- What inclusion and exclusion criteria will you use to identify eligible participants?

- How will you contact your sample – by mail, online, by phone, or in person?

If you’re using a probability sampling method, it’s important that everyone who is randomly selected actually participates in the study. How will you ensure a high response rate?

If you’re using a non-probability method, how will you avoid bias and ensure a representative sample?

Data management

It’s also important to create a data management plan for organising and storing your data.

Will you need to transcribe interviews or perform data entry for observations? You should anonymise and safeguard any sensitive data, and make sure it’s backed up regularly.

Keeping your data well organised will save time when it comes to analysing them. It can also help other researchers validate and add to your findings.

On their own, raw data can’t answer your research question. The last step of designing your research is planning how you’ll analyse the data.

Quantitative data analysis

In quantitative research, you’ll most likely use some form of statistical analysis . With statistics, you can summarise your sample data, make estimates, and test hypotheses.

Using descriptive statistics , you can summarise your sample data in terms of:

- The distribution of the data (e.g., the frequency of each score on a test)

- The central tendency of the data (e.g., the mean to describe the average score)

- The variability of the data (e.g., the standard deviation to describe how spread out the scores are)

The specific calculations you can do depend on the level of measurement of your variables.

Using inferential statistics , you can:

- Make estimates about the population based on your sample data.

- Test hypotheses about a relationship between variables.

Regression and correlation tests look for associations between two or more variables, while comparison tests (such as t tests and ANOVAs ) look for differences in the outcomes of different groups.

Your choice of statistical test depends on various aspects of your research design, including the types of variables you’re dealing with and the distribution of your data.

Qualitative data analysis

In qualitative research, your data will usually be very dense with information and ideas. Instead of summing it up in numbers, you’ll need to comb through the data in detail, interpret its meanings, identify patterns, and extract the parts that are most relevant to your research question.

Two of the most common approaches to doing this are thematic analysis and discourse analysis .

There are many other ways of analysing qualitative data depending on the aims of your research. To get a sense of potential approaches, try reading some qualitative research papers in your field.

A sample is a subset of individuals from a larger population. Sampling means selecting the group that you will actually collect data from in your research.

For example, if you are researching the opinions of students in your university, you could survey a sample of 100 students.

Statistical sampling allows you to test a hypothesis about the characteristics of a population. There are various sampling methods you can use to ensure that your sample is representative of the population as a whole.

Operationalisation means turning abstract conceptual ideas into measurable observations.